Silicone Wristbands as Passive Samplers in Honey Bee Hives

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Band Preparation

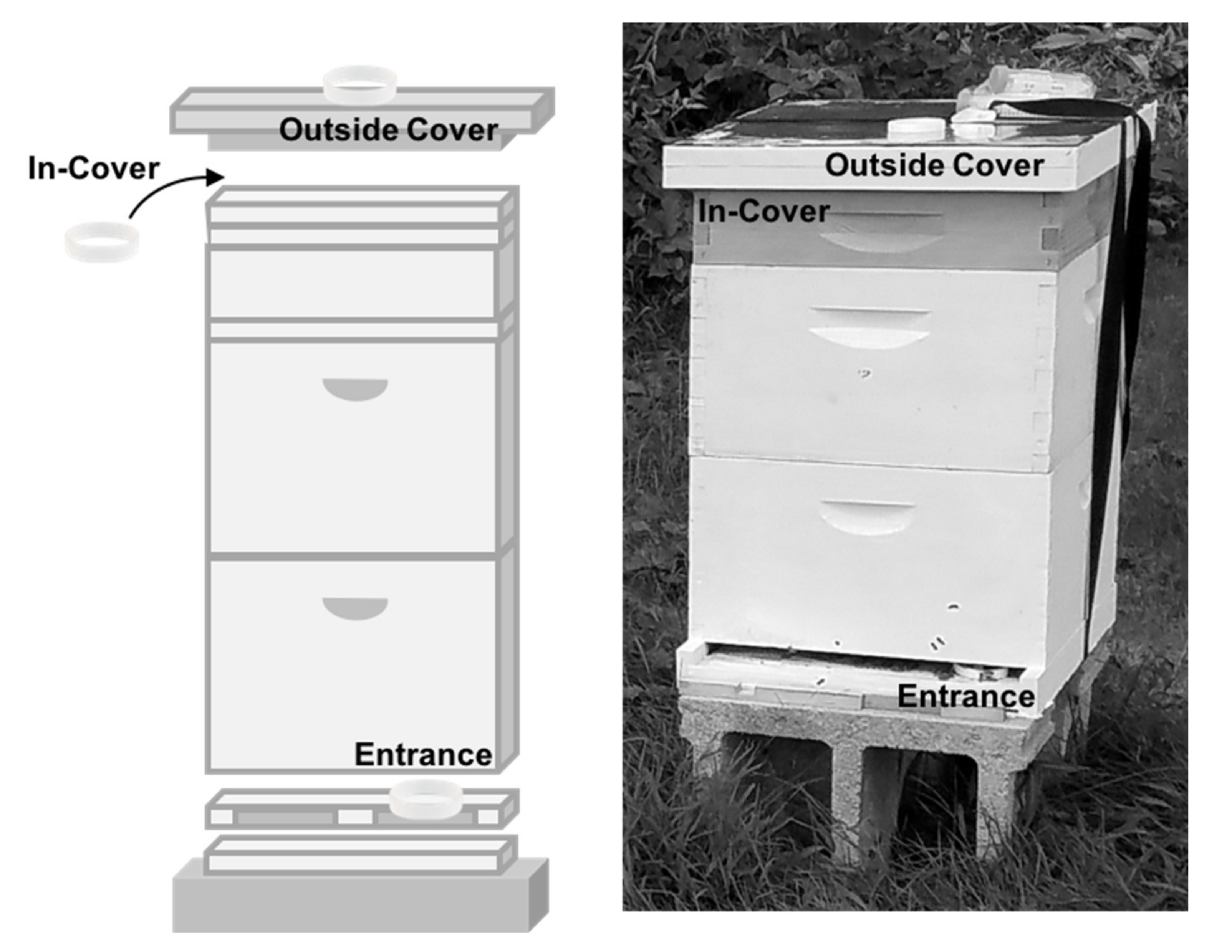

2.3. Band Deployment

2.4. Band Extraction

2.5. Gas Chromatographic Analysis of Band Extracts

3. Results

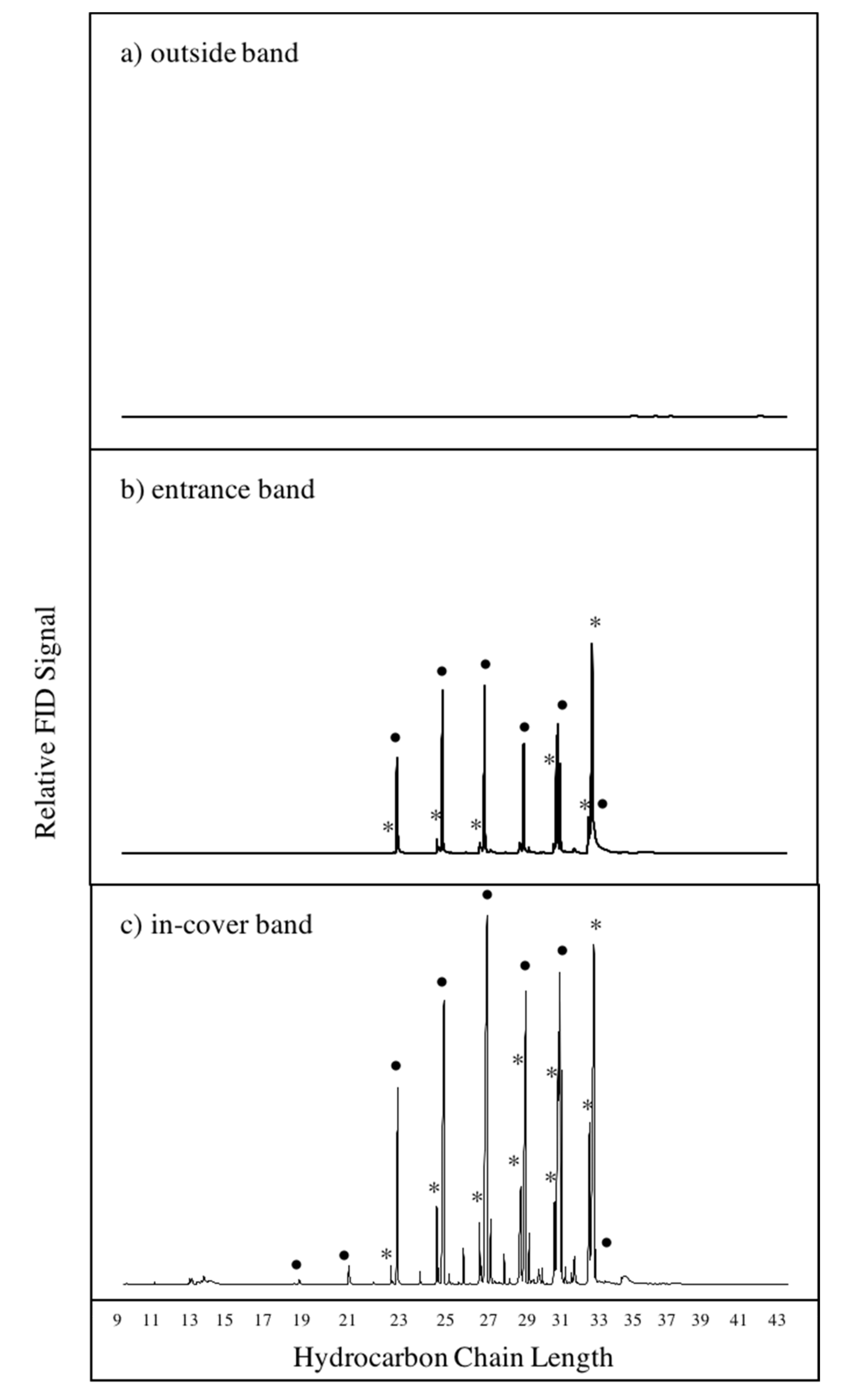

3.1. Chemical Profiles of Hive Air Were Dominated by Hydrocarbon Compounds

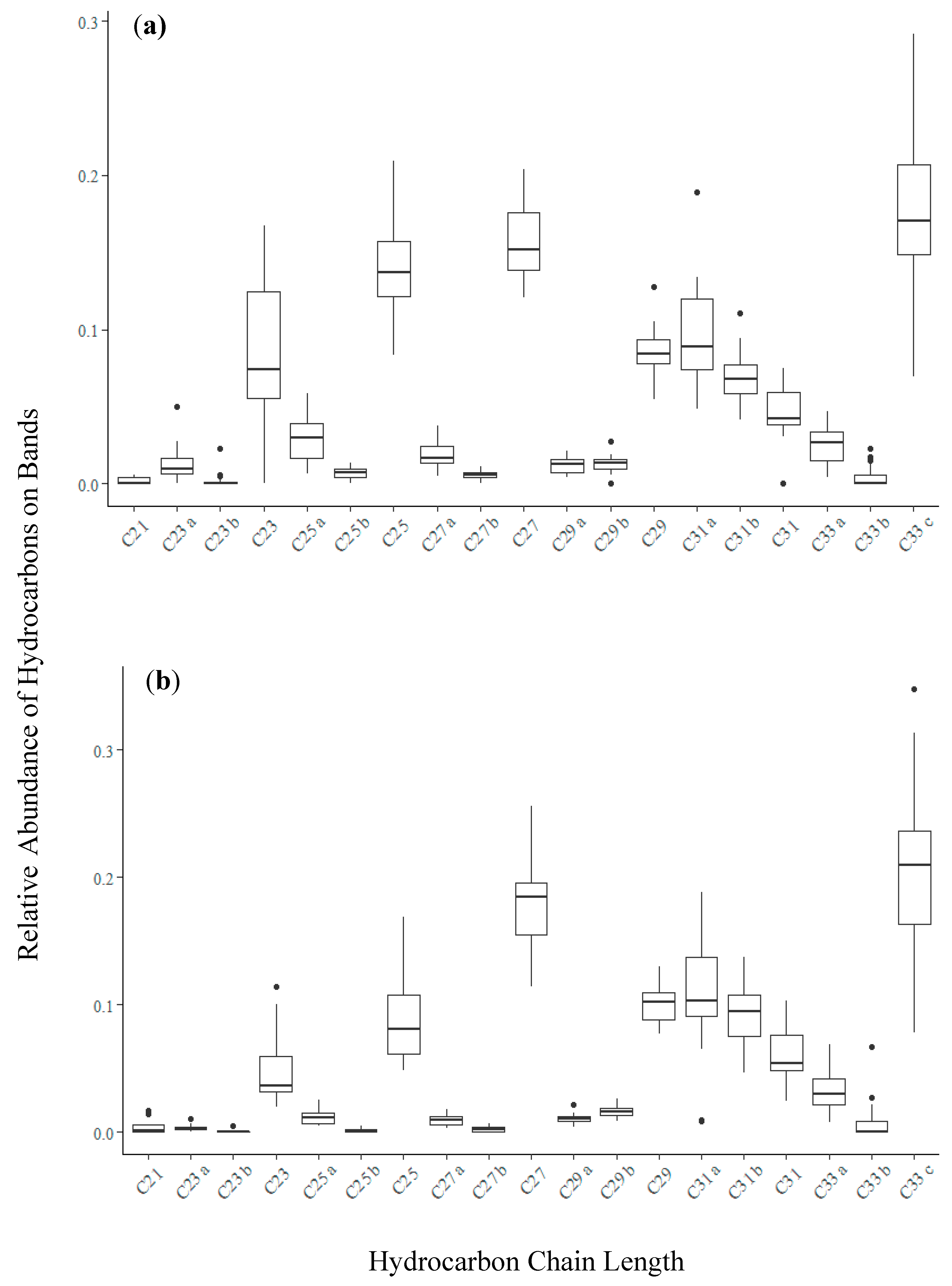

3.2. Bands Adsorbed Bee-Associated Chemicals

3.3. Bands Adsorb Plant-Derived Compounds

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications for Studies of Honey Bee Health

4.2. General Applicability of Bands to Honey Bee Research

4.3. Modifications for Future Studies

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, Y.; Schoville, S.; Bonning, B.; Genersch, E. Ecology/Parasites/Parasitoids/Biological control. In Current Opinion in Insect Science; Jensen, A., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; Volume 26, pp. 1–154. [Google Scholar]

- López-Uribe, M.M.; Simone-Finstrom, M. Special Issue: Honey Bee Research in the US: Current State and Solutions to Beekeeping Problems. Insects 2019, 10, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, A.-M.; Vaissière, B.E.; Cane, J.H.; Steffan-Dewenter, I.; Cunningham, S.A.; Kremen, C.; Tscharntke, T. Importance of pollinators in changing landscapes for world crops. Proc. R. Soc. B 2007, 274, 303–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellis, J.D.; Evans, J.D.; Pettis, J. Colony losses, managed colony population decline, and Colony Collapse Disorder in the United States. J. Apic. Res. 2010, 49, 134–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon-Delso, N.; San Martin, G.; Bruneau, E.; Minsart., L.A.; Mouret, C.; Hautier, L. Honeybee Colony Disorder in Crop Areas: The Role of Pesticides and Viruses. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e103073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- VanEngelsdorp, D.; Evans, J.D.; Saegerman, C.; Mullin, C.; Haubruge, E.; Nguyen, B.K.; Frazier, M.; Frazier, J.; Cox-Foster, D.; Chen, Y.; et al. Colony Collapse Disorder: A Descriptive Study. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e6481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higes, M.; Meana, A.; Bartolomé, C.; Botías, C.; Martín-Hernández, R.N. Ceranae an emergent pathogen for beekeeping. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2013, 5, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broadrup, R.L.; Mayack, C.; Schick, S.J.; Eppley, E.J.; White, H.K.; Macherone, A. Honey bee (Apis mellifera) exposomes and dysregulated metabolic pathways associated with Nosema ceranae infection. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0213249. [Google Scholar]

- Gilley, D.C. Hydrocarbons Emitted by Waggle-Dancing Honey Bees Increase Forager Recruitment by Stimulating Dancing. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e105671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, M.J.; Duehl, A.J. Collection of volatiles from honeybee larvae and adults enclosed on brood frames. Apidologie 2012, 43, 715–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.J.; Zhang, X.C.; Jiang, W.J.; Barron, A.B.; Zhang, J.H.; Zeng, Z.J. Starving honey bee (Apis mellifera) larvae signal pheremonally to worker bees. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Slessor, K.N.; Winston, M.L.; Le Conte, Y. Pheromone communication in the honeybee (Apis mellifera L.). J. Chem. Ecol. 2005, 31, 2731–2745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duassaubat, C.; Maisonnasse, A.; Alaux, C.; Tchamitchan, S.; Brunet, J.-L.; Plettner, E.; Belzunces, L.P.; Le Conte, Y. Nosema spp. Infection Alters Pheromone Production in Honey Bees (Apis mellifera). J. Chem. Ecol. 2010, 36, 522–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richard, F.; Holt, H.L.; Grozinger, C.M. Effects of immunostimulation on social behavior, chemical communication and genome-wide gene expression in honey bee workers (Apis mellifera). BMC Genom. 2012, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, Z.L.; Keyzers, R.A.; Barbieri, R.F.; Digby, A.P.; Lester, P.J. Two pathogens change cuticular hydrocarbon profiles but neither elicit a social behavioural change in infected honey bees, Apis mellifera (Apidae: Hymenoptera). Austral Entomol. 2016, 55, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torto, B.; Carroll, M.J.; Duehl, A.; Fombong, A.T.; Gozansky, T.K.; Nazzi, F.; Soroker, V.; Teal, P.E.A. Standard methods for chemical ecology research in Apis mellifera. J. Apic. Res. 2013, 52, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murcia-Morales, M.; Van der Steen, J.J.; Vejsnæs, F.; Díaz-Galiano, F.J.; Flores, J.M.; Fernández-Alba, A.R. APIStrip, a new tool for environmental contaminant sampling through honeybee colonies. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 138948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, J.A.; Nickerson, G.; James, D.D.; Heider, C. Determination of Essential Oils in Hops by Headspace Solid-Phase Microextraction. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1996, 44, 1768–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agelopoulos, N.G.; Pickett, J.A. Headspace Analysis in Chemical Ecology: Effects of Different Sampling Methods on Ratios of Volatile Compounds Present in Headspace Samples. J. Chem. Ecol. 1998, 24, 1161–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, D.D.; Pollien, P.; Milo, C. Solid-Phase Microextraction Method Development for Headspace Analysis of Volatile Flavor Compounds. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2000, 48, 2430–2437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilley, D.C.; Degrandi-Hoffman, G.; Hooper, J.E. Volatile compounds emitted by live European honey bee (Apis mellifera L.) queens. J. Insect Physiol. 2006, 52, 520–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connell, S.G.; Kincl, L.D.; Anderson, K.A. Silicone Wristbands as Personal Passive Samplers. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 3327–3335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donald, C.E.; Scott, R.P.; Blaustein, K.L.; Halbleib, M.L.; Sarr, M.; Jepson, P.C.; Anderson, K.A. Silicone wristbands detect individuals’ pesticide exposures in West Africa. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2016, 3, 160433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, K.A.; Points, G.L., III; Donald, C.E.; Dixon, H.M.; Scott, R.P.; Wilson, G.; Tidwell, L.G.; Hoffman, P.D.; Herbstman, J.B.; O’Connelll, S.G. Preparation and performance features of wristband samplers and considerations for chemical exposure assessment. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 2017, 27, 551–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammel, S.C.; Hoffman, K.; Webster, T.F.; Anderson, K.A.; Stapleton, H.M. Measuring Personal Exposure to Organophosphate Flame Retardants Using Silicone Wristbands and Hand Wipes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 4483–4491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammel, S.C.; Phillips, A.L.; Hoffman, K.; Stapleton, H.M. Evaluating the Use of Silicone Wristbands to Measure Personal Exposure to Brominated Flame Retardants. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 11875–11885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attari, S.G.; Bahrami, A.; Shahna, F.G.; Heidari, M. Solid-phase microextraction fiber development for sampling and analysis of volatile organohalogen compounds in air. J. Environ. Health Sci. Eng. 2014, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dani, F.R.; Jones, G.R.; Corsi, S.; Beard, R.; Pradella, D.; Turillazzi, S. Nestmate Recognition Cues in the Honey Bee: Differential Importance of Cuticular Alkanes and Alkenes. Chem. Senses 2005, 30, 477–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strachecka, A.; Borsuk, G.; Paleolog, J.; Olszewski, K.; Bajda, M.; Chobotow, J. Body-surface Compounds in Buckfast and Caucasian Honey Bee Workers (Apis mellifera). J. Apic. Sci. 2014, 58, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kather, R.; Drijfhout, F.P.; Martin, S.J. Evidence for colony-specific differences in chemical mimicry in the parasitic mite Varroa destructor. Chemoecology 2015, 25, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trhlin, M.; Rajchard, J. Chemical communication in the honeybee (Apis mellifera L.): A review. Vet. Med. 2011, 56, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mărgăoan, R.; Mărghitaş, L.A.; Dezmirean, D.S.; Dulf, F.V.; Bunea, A.; Socaci, S.A.; Bobiş, O. Predominant and Secondary Pollen Botanical Origins Influence the Carotenoid and Fatty Acid Profile in Fresh Honeybee-Collected Pollen. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 6306–6316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchwald, R.; Breed, M.D.; Bjostad, L.; Hibbard, B.E.; Greenberg, A.R. The role of fatty acids in the mechanical properties of beeswax. Apidologie 2009, 40, 585–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teerawanichpan, P.; Robertson, A.J.; Qiu, X. A fatty acyl-CoA reductase highly expressed in the head of honey bee (Apis mellifera) involves biosynthesis of a wide range of aliphatic fatty alcohols. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2010, 40, 641–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zalewski, K.; Zaobidna, E.; Żóltowska, K. Fatty acid composition of the parasitic mite Varroa destructor and its host the worker prepupae of Apis mellifera. Phys. Entom. 2016, 41, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, L.; Ahmad, R.; Rehman, N.U.; Khan, A.L.; Hassan, Z.; Rizvi, T.S.; Al-Harrasi, A.; Shinwari, Z.K.; Hussain, J. A New Cyclopropyl-Triterpenoid from Ochradenus arabicus. Helv. Chim. Acta 2016, 98, 1240–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vit, P.; Soler, C.; Tomás-Barberán, F.A. Profiles of phenolic compounds of Apis mellifera and Melipona spp. honeys from Venezuela. Z. Lebensm. Unters. Forsch. A 1997, 204, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okosun, O.O.; Yusuf, A.A.; Crewe, R.M.; Pirk, C.W.W. Effects of age and Reproductive Status on Tergal Gland Secretions in Queenless Honey bee Workers, Apis mellifera scutellata and A. m. capensis. J. Chem. Ecol. 2015, 41, 896–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terzo, M.; Urbanova, K.; Valerova, I.; Rasmont, P. Intra and interspecific variability of the cephalic labial glands’ secretions in male bumblebees: The case of Bombus (Thoracobombus) ruderarius and B. (Thoracobombus) sylvarum [Hymenoptera, Apidae]. Apidologie 2005, 36, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hazardous Substances Data Bank (HSDB): A TOXNET Database. Available online: https://toxnet.nlm.nih.gov/newtoxnet/hsdb.htm (accessed on 26 March 2019).

- Coleman, R.; Penner, D. Organic Acid Enhancement of Pelargonic Acid. Weed Tech. 2008, 22, 38–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, P.K.; Sing, N.; Ahmad, G.; Dube, A.; Maurya, R. Glycolipids and other constituents from Desmodium gangeticum with antileishmanial and immunomodulatory activities. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2005, 15, 4543–4546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamboj, A.; Pooja, A.; Saluja, A.K. Isolation and Characterization of Bioactive Compounds from the Petroleum Ether Extracts of Leaves of Xanthium Strumarium Linn. BioMedRx 2013, 1, 235–238. [Google Scholar]

- Yoneyama, K.; Natsume, M. Phenolic Compounds. In Comprehensive Natural Products II; Mander, L., Liu, H.-W., Eds.; Elsevier: Kidlington, UK, 2010; Volume 1, pp. 539–558. [Google Scholar]

- Widhalm, J.R.; Dudareva, N.A. A Familiar Ring to It: Biosynthesis of Plant Benzoic Acids. Mol. Plant 2015, 8, 83–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasmont, P.; Regali, A.; Ings, T.C.; Lognay, G.; Baudart, E.; Marlier, M.; Delcarte, E.; Viville, P.; Marot, C.; Falmagne, P.; et al. Analysis of Pollen and Nectar of Arbutus unedo as a Food Source for Bombus terrestris (Hymenoptera: Apidae). J. Econ. Entomol. 2005, 98, 656–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicolson, S.W. Bee Food: The Chemistry and Nutritional Value of Nectar, Pollen and Mixtures of the Two. Afr. Zool. 2011, 46, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aerts, R.; Joly, L.; Szternfeld, P.; Tsilikas, K.; De Cremer, K.; Castelain, P.; Aerts, J.M.; Van Orshoven, J.; Somers, B.; Hendrickx, M.; et al. Silicone Wristband Passive Samplers Yield Highly Individualized Peticide Residue Exposure Profiles. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 298–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Compound Type | Chain Lengths | Log Kow Range | % of Bands a | Association with Honey Bees |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alkanes | C21–C33 odd chain lengths only | 10.7–16.6 b | 44–95 | nestmate recognition semiochemical [15,28,29,30,38] |

| queen tergal gland secretion [38] | ||||

| waggle dance (C23 and C25 only) [9,31] | ||||

| Alkenes | C23–C33 b odd chain lengths only | 11.4–16.4 b | 7–93 | nestmate recognition semiochemical [29,30,31,33] |

| queen tergal gland secretion [38] | ||||

| waggle dance (C23 and C25 only) [9,31] | ||||

| Fatty acids | C12:0–C30:0 | 3.42–13.8 | 53–97 | detected in worker bees (C12:0–C22:0; C26:0–C30:0 even chain lengths) [34,35] |

| detected in Varroa destructor (C23:0–C24:0) [35] | ||||

| Unsaturated fatty acids | C18:1 (oleic acid) | 7.64 | 96 | major constituent—beeswax [35] detected in worker bees [34,35] |

| C18:2 (linoleic acid) | 7.05 | 81 | major constituent—beeswax [31] | |

| detected in worker bees [34,35] | ||||

| C18:3 (α-linolenic acid) | 6.46 | 48 | major constituent—beeswax [31] | |

| detected in worker bees [34,35] | ||||

| Fatty alcohols | C16–C32 | 6.83–14.10 b | 36–96 | queen retinue pheromone (QRP) (C16) [31] |

| drone cocoon (C17) [36] | ||||

| detected in worker bees (C18–C32) [34] | ||||

| C19 c | 40 | detected in Bombus ruderarius and Bombus sylvarum (Hymenoptera, Apidae) [39] | ||

| C19 c,d | 76 | detected in Bombus ruderarius and B. sylvarum (Hymenoptera, Apidae) [39] | ||

| C20 c [Z]-11-eicosenol | 76 | alarm pheromone [31,34] | ||

| Other | Chrysin | 3.52 | 13 | honey, propolis, and beeswax [37] |

| Glycerol | -1.76 | 78 | ester biosynthesis in honey bees [31] |

| Compound Group | Compounds | Log Kow Range26 | % of Bands a | Associations with Plants |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fatty acids | C10:0–C20:0; C22:0 | 4.0–9.9 | 64–97 | pollen [32] |

| C9:0 | 3.42 | 84 | nonselective herbicide [41] | |

| Unsaturated fatty acids | C18:1 (oleic acid) | 7.64 | 96 | |

| C18:2 (linoleic acid) | 7.05 | 81 | all major constituents of pollen [32] | |

| C18:3 (α-linolenic acid) | 6.46 | 48 | ||

| Fatty alcohols | C33 | 13 | plant origin [42,43] | |

| Bnzoic and cinnamic acid derivatives | benzoic acid | 1.87 | 79 | |

| cinnamic acid, p-methoxy | 2.68 | 63 | ||

| cinnamyl cinnamate | 3.96 | 12 | plant originated allelochemicals [44,45] | |

| 4-hydroxybenzoic acid | 1.58 | 12 | ||

| hydrocinnamic acid | 1.84 | 10 | ||

| benzyl cinnamate | 3.44 | 9 | ||

| ferulic acid | 1.51 | 7 | ||

| cinnamic acid, 3,4-dihydroxy- | 1.15 | 3 | ||

| benzyl salicylate | 4.31 b | 3 | ||

| Sterols | beta-sitosterol (29Δ (5)) | 9.65 b | 43 | pollen [46] |

| stigmasterol (29Δ (5, 22)) | 9.43 | 13 | pollen [46] | |

| lanosta-8,24-dien-3-ol, acetate, (2, β)- | 11.8 b | 9 | pollen [46] | |

| Sugars | d-mannose | −3.38 b | 9 | nectar [47] |

| d-glucose | −2.82 | 6 | nectar [47] | |

| d-glucopyranose | −2.82 | 3 | nectar [47] | |

| d-xylose | −2.74 b | 3 | nectar [47] |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bullock, E.J.; Schafsnitz, A.M.; Wang, C.H.; Broadrup, R.L.; Macherone, A.; Mayack, C.; White, H.K. Silicone Wristbands as Passive Samplers in Honey Bee Hives. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 86. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci7030086

Bullock EJ, Schafsnitz AM, Wang CH, Broadrup RL, Macherone A, Mayack C, White HK. Silicone Wristbands as Passive Samplers in Honey Bee Hives. Veterinary Sciences. 2020; 7(3):86. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci7030086

Chicago/Turabian StyleBullock, Emma J., Alexis M. Schafsnitz, Chloe H. Wang, Robert L. Broadrup, Anthony Macherone, Christopher Mayack, and Helen K. White. 2020. "Silicone Wristbands as Passive Samplers in Honey Bee Hives" Veterinary Sciences 7, no. 3: 86. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci7030086

APA StyleBullock, E. J., Schafsnitz, A. M., Wang, C. H., Broadrup, R. L., Macherone, A., Mayack, C., & White, H. K. (2020). Silicone Wristbands as Passive Samplers in Honey Bee Hives. Veterinary Sciences, 7(3), 86. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci7030086