Dogs (Canis familiaris) as Sentinels for Human Infectious Disease and Application to Canadian Populations: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. One Health

1.2. Sentinel Surveillance

1.3. Dogs as Sentinels

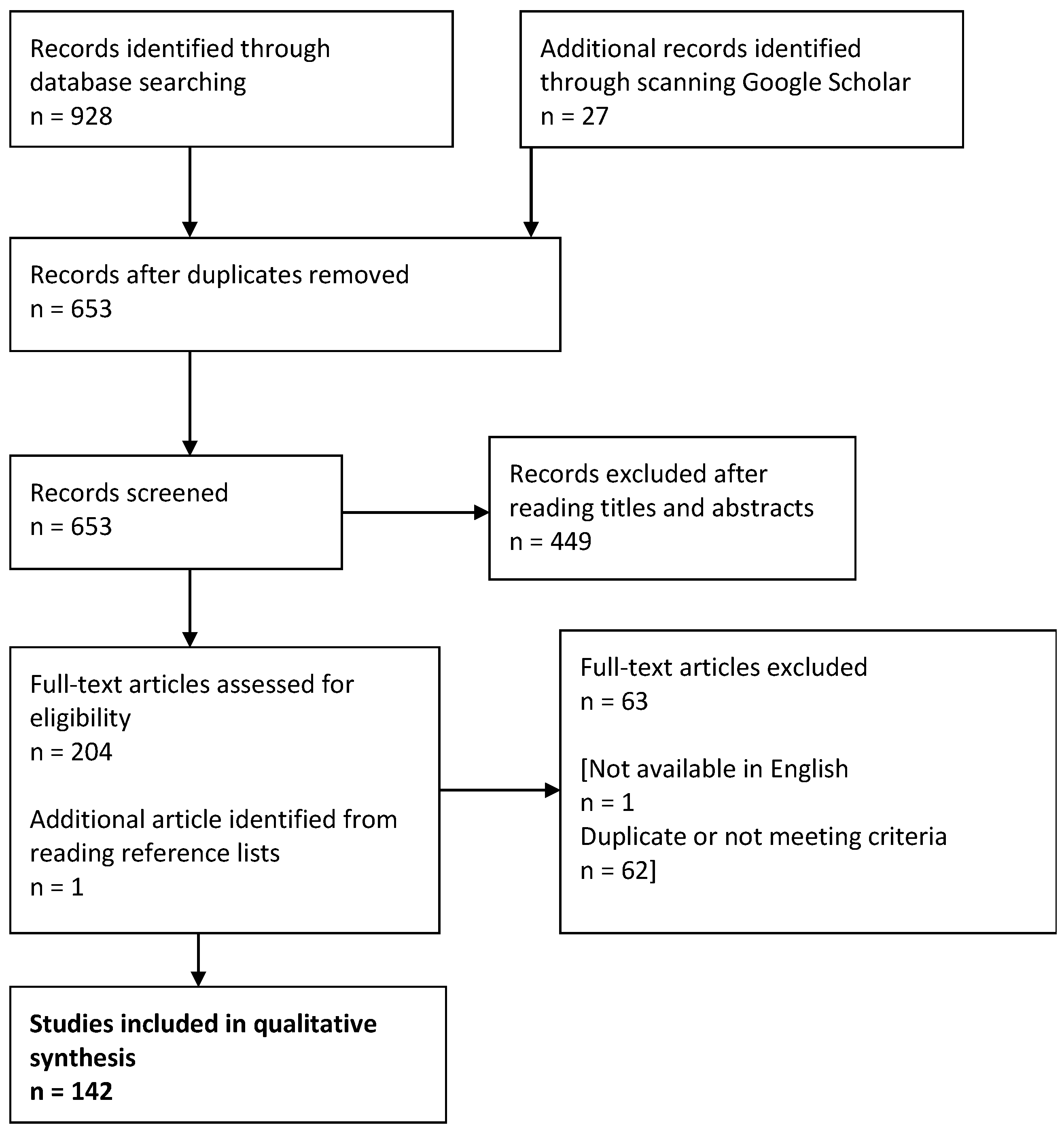

2. Materials and Methods

- Globally, what research has been undertaken related to the current use or suggestion of dogs as sentinels for human infectious disease?

- How much of this research is related to Canadian populations, and which research could be applied to Canadian populations?

3. Review of the Global Literature

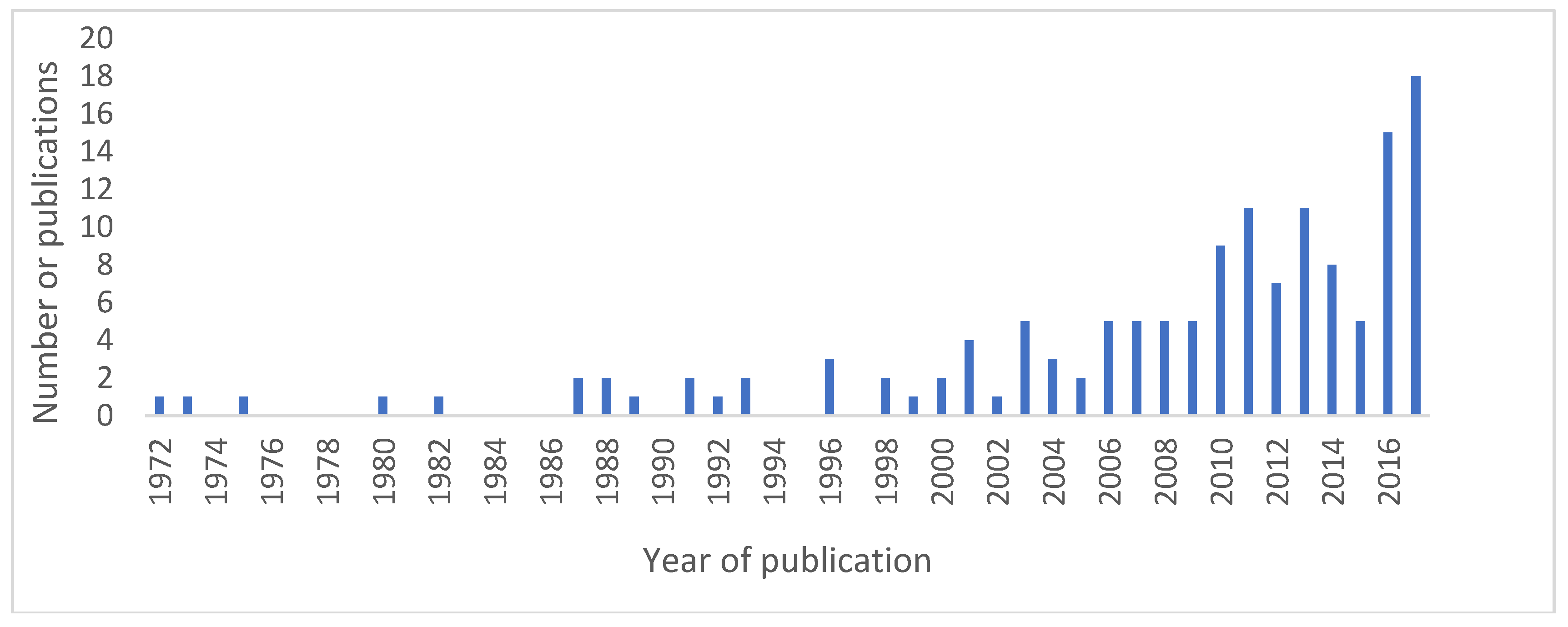

3.1. Description of Obtained Results

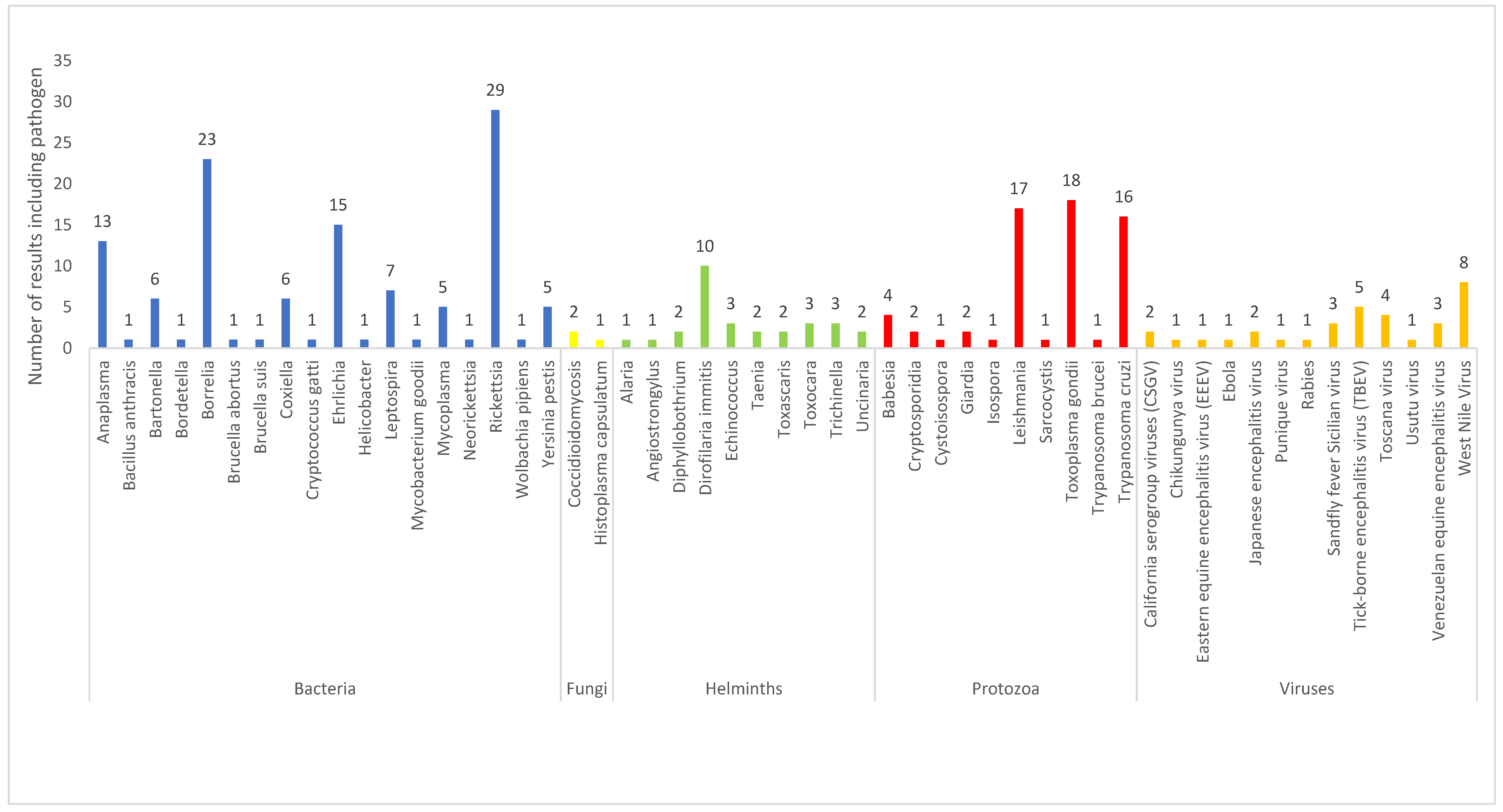

3.2. Description of Results by Type of Infectious Agent

3.2.1. Viruses

3.2.2. Bacteria

3.2.3. Protozoa

3.2.4. Fungi

3.2.5. Helminths

4. Review and Discussion of Dog-Sentinel Surveillance in Canada

4.1. Publications and First Nations (Indigenous) Communities in Canada

4.2. Viruses

4.2.1. Arboviruses

4.2.2. West Nile Virus

4.3. Bacteria

4.3.1. Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever

4.3.2. Anaplasma

4.3.3. Borrelia

4.3.4. Ehrlichia

4.4. Protozoa

4.4.1. Toxoplasma gondii

4.4.2. Babesia

4.5. Helminths

Dirofilaria immitis

4.6. Fungi

5. Limitations of the Review

6. Implementing a Dog-Sentinel Surveillance System: General Principles and Limitations

7. Recommendations

8. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- One Health Comission. One Health Commission: What Is One Health? Available online: https://www.onehealthcommission.org/en/why_one_health/what_is_one_health/ (accessed on 31 May 2018).

- Gibbs, E.P.J. The evolution of one health: A decade of progress and challenges for the future. Vet. Rec. 2014, 174, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lerner, H.; Berg, C. The concept of health in one health and some practical implications for research and education: What is one health? Infect. Ecol. Epidemiol. 2015, 5, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welburn, S. One health: The 21st century challenge. Vet. Rec. 2011, 168, 614–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zinsstag, J.; Mackenzie, J.S.; Jeggo, M.; Heymann, D.L.; Patz, J.A.; Daszak, P. Mainstreaming one health. EcoHealth 2012, 9, 107–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.; Brumme, Z.L. Operationalizing the one health approach: The global governance challenges. Health Policy Plan. 2013, 28, 778–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woolhouse, M.E.J. Population biology of emerging and re-emerging pathogens. Trends Microbiol. 2002, 10, s3–s7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millar, B.C.; Moore, J.E. Emerging pathogens in infectious diseases: Definitions, causes and trends. Rev. Med. Microbiol. 2006, 17, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, L.H.; Latham, S.M.; Woolhouse, M.E.J. Risk factors for human disease emergence. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2001, 356, 983–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, K.E.; Patel, N.G.; Levy, M.A.; Storeygard, A.; Balk, D.; Gittleman, J.L.; Daszak, P. Global trends in emerging infectious diseases. Nature 2008, 451, 990–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cleaveland, S.; Laurenson, M.K.; Taylor, L.H. Diseases of humans and their domestic mammals: Pathogen characteristics, host range and the risk of emergence. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2001, 356, 991–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woolhouse, M.; Gowtage-Sequeria, S. Host range and emerging and reemerging pathogens. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2005, 11, 1842–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCluskey, B.J. Use of sentinel herds in monitoring and surveillance systems. In Animal Disease Surveillance and Survey Systems: Methods and Applications; Salman, M.D., Ed.; Iowa State Press: Ames, IA, USA, 2003; pp. 119–133. [Google Scholar]

- OED. Oxford English Dictionary Online; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK; Available online: https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/sentinel (accessed on 17 September 2018).

- Schmidt, P.L. Companion animals as sentinels for public health. Vet. Clin. North Am. Small Anim. Pract. 2009, 39, 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halliday, J.E.B.; Meredith, A.L.; Knobel, D.L.; Shaw, D.J.; Bronsvoort, B.; Cleaveland, S. A framework for evaluating animals as sentinels for infectious disease surveillance. J. R. Soc. Interface 2007, 4, 973–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Resnick, M.P.; Grunenwald, P.; Blackmar, D.; Hailey, C.; Bueno, R.; Murray, K.O. Juvenile dogs as potential sentinels for West Nile virus surveillance. Zoonoses Public Health 2008, 55, 443–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabinowitz, P.M.; Gordon, Z.; Holmes, R.; Taylor, B.; Wilcox, M.; Chudnov, D.; Nadkarni, P.; Dein, F.J. Animals as sentinels of human environmental health hazards: An evidence-based analysis. EcoHealth 2005, 2, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- University of Washington. Canary Database: Animals as Sentinels for Human Environmental Health Hazards. Available online: https://canarydatabase.org/ (accessed on 16 September 2018).

- Cleaveland, S.; Meslin, F.X.; Breiman, R. Dogs can play useful role as sentinel hosts for disease. Nature 2006, 440, 605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schurer, J.M.; Ndao, M.; Quewezance, H.; Elmore, S.A.; Jenkins, E.J. People, pets, and parasites: One health surveillance in southeastern saskatchewan. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2014, 90, 1184–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cleaveland, S.; Kaare, M.; Knobel, D.; Laurenson, M.K. Canine vaccination—Providing broader benefits for disease control. Vet. Microbiol. 2006, 117, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabinowitz, P.M.; Odofin, L.; Dein, F.J. From “us vs. them” to “shared risk”: Can animals help link environmental factors to human health? EcoHealth 2008, 5, 224–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burns, K. JAVMA news. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2007, 230, 1600–1620. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The prisma statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 151, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Bank. Data: World Bank Country and Lending Groups. Available online: https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups (accessed on 29 May 2018).

- Molyneux, D.H. Combating the “other diseases” of MDG 6: Changing the paradigm to achieve equity and poverty reduction? Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2008, 102, 509–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maudlin, I.; Eisler, M.C.; Welburn, S.C. Neglected and endemic zoonoses. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2009, 364, 2777–2787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okello, A.L.; Welburn, S.C. Global health a challenge for interdisciplinary research. In 8. Inter-Disciplinary Health Approaches for Poverty Alleviation: Control of Neglected Zzoonoses in Developing Countries; Kappas, M., Groß, U., Kelleher, D., Eds.; Universitätsverlag Göttingen: Göttingen, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Davoust, B.; Leparc-Goffart, I.; Demoncheaux, J.P.; Tine, R.; Diarra, M.; Trombini, G.; Mediannikov, O.; Marie, J.L. Serologic surveillance for West Nile virus in dogs, Africa. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2014, 20, 1415–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komar, N.; Panella, N.A.; Boyce, E. Exposure of domestic mammals to West Nile virus during an outbreak of human encephalitis, New York City, 1999. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2001, 7, 736–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kile, J.C.; Panella, N.A.; Komar, N.; Chow, C.C.; MacNeil, A.; Robbins, B.; Bunning, M.L. Serologic survey of cats and dogs during an epidemic of West Nile virus infection in humans. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2005, 226, 1349–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durand, B.; Haskouri, H.; Lowenski, S.; Vachiery, N.; Beck, C.; Lecollinet, S. Seroprevalence of West Nile and Usutu viruses in military working horses and dogs, Morocco, 2012: Dog as an alternative WNV sentinel species? Epidemiol. Infect. 2016, 144, 1857–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocheleau, J.P.; Michel, P.; Lindsay, L.R.; Drebot, M.; Dibernardo, A.; Ogden, N.H.; Fortin, A.; Arsenault, J. Emerging arboviruses in Quebec, Canada: Assessing public health risk by serology in humans, horses and pet dogs. Epidemiol. Infect. 2017, 145, 2940–2948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lan, D.; Ji, W.; Yu, D.; Chu, J.; Wang, C.; Yang, Z.; Hua, X. Serological evidence of West Nile virus in dogs and cats in China. Arch. Virol. 2011, 156, 893–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breitschwerdt, E.B.; Moncol, D.J.; Corbett, W.T.; MacCormack, J.N.; Burgdorfer, W.; Ford, R.B.; Levy, M.G. Antibodies to spotted fever-group rickettsiae in dogs in North Carolina. Am. J. Vet. Res. 1987, 48, 1436–1440. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Comer, J.A.; Vargas, M.C.; Poshni, I.; Childs, J.E. Serologic evidence of Rickettsia akari infection among dogs in a metropolitan city. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2001, 218, 1780–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elchos, B.N.; Goddard, J. Implications of presumptive fatal Rocky Mountain spotted fever in two dogs and their owner. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2003, 223, 1450–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McQuiston, J.H.; Guerra, M.A.; Watts, M.R.; Lawaczeck, E.; Levy, C.; Nicholson, W.L.; Adjemian, J.; Swerdlow, D.L. Evidence of exposure to spotted fever group rickettsiae among Arizona dogs outside a previously documented outbreak area. Zoonoses Public Health 2011, 58, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Lemos, E.R.S.; Machado, R.D.; Coura, J.R.; Guimaraes, M.A.A.M.; Chagas, N. Epidemiological aspects of the Brazilian spotted fever: Serological survey of dogs and horses in an endemic area in the state of Sao Paulo, Brazil. Rev. Inst. Med. Trop. Sao Paulo 1996, 38, 427–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinter, A.; Horta, M.C.; Pacheco, R.C.; Moraes Filho, J.; Labruna, M.B. Serosurvey of Rickettsia spp. in dogs and humans from an endemic area for Brazilian spotted fever in the state of Sao Paulo, Brazil. Cad. Saude Publica 2008, 24, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milagres, B.S.; Padilha, A.F.; Barcelos, R.M.; Gomes, G.G.; Montandon, C.E.; Pena, D.C.H.; Bastos, F.A.N.; Silveira, I.; Pacheco, R.; Labruna, M.B.; et al. Rickettsia in synanthropic and domestic animals and their hosts from two areas of low endemicity for Brazilian spotted fever in the eastern region of Minas Gerais, Brazil. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2010, 83, 1305–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunha, N.C.D.; de Lemos, E.R.S.; Rozental, T.; Teixeira, R.C.; Cordeiro, M.D.; Lisboa, R.S.; Favacho, A.R.; Barreira, J.D.; Rezende, J.D.; Fonseca, A.H.D. Rickettsiae of the spotted fever group in dogs, horses and ticks: An epidemiological study in an endemic region of the State of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Rev. Bras. Med. Vet. 2014, 36, 294–300. [Google Scholar]

- Galvao, M.A.M.; Cardoso, L.D.; Mafra, C.L.; Calic, S.B.; Walker, D.H. Revisiting Brazilian spotted fever focus of caratinga, Minas Gerais State, Brazil. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2006, 1078, 255–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otomura, F.H.; Truppel, J.H.; Moraes Filho, J.; Labruna, M.B.; Rossoni, D.F.; Massafera, R.; Soccol, V.T.; Teodoro, U. Probability of occurrence of the Brazilian spotted fever in northeast of Parana state, Brazil. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Vet. 2016, 25, 394–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreira-Soto, A.; Carranza, M.V.; Taylor, L.; Calderon-Arguedas, O.; Hun, L.; Troyo, A. Exposure of dogs to spotted fever group rickettsiae in urban sites associated with human rickettsioses in Costa Rica. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2016, 7, 748–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, P.J.; Mason, P.R. Tick-bite fever in Zimbabwe. Survey of antibodies to rickettsia conorii in man and dogs, and of rickettsia-like organisms in dog ticks. S. Afr. Med. J. 1991, 80, 233–236. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Salb, A.L.; Barkema, H.W.; Elkin, B.T.; Thompson, R.C.A.; Whiteside, D.P.; Black, S.R.; Dubey, J.R.; Kutz, S.J. Dogs as sources and sentinels of parasites in humans and wildlife, northern Canada. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2008, 14, 60–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benitez, A.D.; Martins, F.D.C.; Mareze, M.; Santos, N.J.R.; Ferreira, F.P.; Martins, C.M.; Garcia, J.L.; Mitsuka-Bregano, R.; Freire, R.L.; Biondo, A.W.; et al. Spatial and simultaneous representative seroprevalence of anti-Toxoplasma gondii antibodies in owners and their domiciled dogs in a major city of southern Brazil. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0180906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Constantino, C.; Pellizzaro, M.; de Paula, E.F.E.; Vieira, T.S.W.J.; Brandao, A.P.D.; Ferreira, F.; Vieira, R.F.D.C.; Langoni, H.; Biondo, A.W. Serosurvey for leishmania spp., Toxoplasma gondii, Trypanosoma cruzi and Neospora caninum in neighborhood dogs in Curitiba-Parana, Brazil. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Vet. 2016, 25, 504–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meireles, L.R.; Galisteo Junior, A.J.; Pompeu, E.; Andrade Junior, H.F. Toxoplasma gondii spreading in an urban area evaluated by seroprevalence in free-living cats and dogs. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2004, 9, 876–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Silva, J.R.; Maciel, B.M.; de Santana Souza Santos, L.K.N.; Carvalho, F.S.; de Santana Rocha, D.; Lopes, C.W.G.; Albuquerque, G.R. Isolation and genotyping of Toxoplasma gondii in Brazilian dogs. Korean J. Parasitol. 2017, 55, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da Silva, R.C.; de Lima, V.Y.; Tanaka, E.M.; da Silva, A.V.; de Souza, L.C.; Langoni, H. Risk factors and presence of antibodies to Toxoplasma gondii in dogs from the coast of Sao Paulo State, Brazil. Pesqui. Vet. Bras. 2010, 30, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordeiro, R.A.; Coelho, C.G.V.; Brilhante, R.S.N.; Sidrim, J.J.C.; Castelo-Branco, D.S.C.M.; Moura, F.B.P.; Rocha, F.A.C.; Rocha, M.F.G. Serological evidence of Histoplasma capsulatum infection among dogs with leishmaniasis in Brazil. Acta Trop. 2011, 119, 203–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gautam, R.; Srinath, I.; Clavijo, A.; Szonyi, B.; Bani-Yaghoub, M.; Park, S.; Ivanek, R. Identifying areas of high risk of human exposure to coccidioidomycosis in Texas using serology data from dogs. Zoonoses Public Health 2013, 60, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grayzel, S.E.; Martinez-Lopez, B.; Sykes, J.E. Risk factors and spatial distribution of canine Coccidioidomycosis in California, 2005–2013. Transbound Emerg. Dis. 2017, 64, 1110–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryan, H.M.; Darimont, C.T.; Paquet, P.C.; Ellis, J.A.; Goji, N.; Gouix, M.; Smits, J.E. Exposure to infectious agents in dogs in remote coastal British Columbia: Possible sentinels of diseases in wildlife and humans. Can. J. Vet. Res. 2011, 75, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Henn, J.B.; Gabriel, M.W.; Kasten, R.W.; Brown, R.N.; Theis, J.H.; Foley, J.E.; Chomel, B.B. Gray foxes (urocyon cinereoargenteus) as a potential reservoir of a Bartonella clarridgeiae-like bacterium and domestic dogs as part of a sentinel system for surveillance of zoonotic arthropod-borne pathogens in Northern California. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2007, 45, 2411–2418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowman, D.; Little, S.E.; Lorentzen, L.; Shields, J.; Sullivan, M.P.; Carlin, E.P. Prevalence and geographic distribution of Dirofilaria immitis, Borrelia burgdorferi, Ehrlichia canis, and Anaplasma phagocytophilum in dogs in the United States: Results of a national clinic-based serologic survey. Vet. Parasitol. 2009, 160, 138–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irwin, P.J.; Robertson, I.D.; Westman, M.E.; Perkins, M.; Straubinger, R.K. Searching for Lyme Borreliosis in Australia: Results of a canine sentinel study. Parasit. Vectors 2017, 10, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Paiva Diniz, P.P.V.; Schwartz, D.S.; de Morais, H.S.A.; Breitschwerdt, E.B. Surveillance for zoonotic vector-borne infections using sick dogs from southeastern Brazil. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2007, 7, 689–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Constantino, C.; de Paula, E.F.E.; Brandao, A.P.D.; Ferreira, F.; da Costa Vieira, R.F.; Biondo, A.W. Survey of spatial distribution of vector-borne disease in neighborhood dogs in southern Brazil. Open Vet. J. 2017, 7, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schule, C.; Rehbein, S.; Shukullari, E.; Rapti, D.; Reese, S.; Silaghi, C. Police dogs from Albania as indicators of exposure risk to Toxoplasma gondii, Neospora caninum and vector-borne pathogens of zoonotic and veterinary concern. Vet. Parasitol. Reg. Stud. Rep. 2015, 1, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, J.K.; Crawford, P.C.; Lappin, M.R.; Dubovi, E.J.; Levy, M.G.; Alleman, R.; Tucker, S.J.; Clifford, E.L. Infectious diseases of dogs and cats on Isabela Island, Galapagos. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2008, 22, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardoso, L.; Mendao, C.; de Carvalho, L.M. Prevalence of Dirofilaria immitis, Ehrlichia canis, Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato, Anaplasma spp. and Leishmania infantum in apparently healthy and CVBD-suspect dogs in Portugal-a national serological study. Parasit. Vectors 2012, 5, 555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schurer, J.M.; Hill, J.E.; Fernando, C.; Jenkins, E.J. Sentinel surveillance for zoonotic parasites in companion animals in indigenous communities of Saskatchewan. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2012, 87, 495–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerjee, S.; Stephen, C.; Fernando, K.; Coffey, S.; Dong, M. Evaluation of dogs as sero-indicators of the geographic distribution of Lyme borreliosis in British Columbia. Can. Vet. J. 1996, 37, 168–169. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Drebot, M.; National Microbiology Laboratory. Emerging Arboviruses: Diagnostic Challenges and Virological Surprises Presentation. Available online: https://www.publichealthontario.ca/en/LearningAndDevelopment/EventPresentations/Arbovirus_apr%206.pdf (accessed on 29 May 2018).

- Kulkarni, M.A.; Berrang-Ford, L.; Buck, P.A.; Drebot, M.A.; Lindsay, L.R.; Ogden, N.H. Major emerging vector-borne zoonotic diseases of public health importance in Canada. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2015, 4, e33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webster, D.; Dimitrova, K.; Holloway, K.; Makowski, K.; Safronetz, D.; Drebot, M.A. California serogroup virus infection associated with encephalitis and cognitive decline, Canada, 2015. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2017, 23, 1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Government of Canada. West Nile Virus and Other Mosquito-Borne Disease National Surveillance Report. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/diseases-conditions/west-nile-virus-other-mosquito-borne-disease-national-surveillance-report-2016-final-summary.html (accessed on 29 May 2018).

- Kulkarni, M.A.; Lecocq, A.C.; Artsob, H.; Drebot, M.A.; Ogden, N.H. Epidemiology and aetiology of encephalitis in Canada, 1994–2008: A case for undiagnosed arboviral agents? Epidemiol. Infect. 2013, 141, 2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godsey, M.S., Jr.; Amoo, F.; Yuill, T.M.; DeFoliart, G.R. California serogroup virus infections in Wisconsin domestic animals. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1988, 39, 409–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, V.; Fazil, A.; Gachon, P.; Deuymes, G.; Radojevic, M.; Mascarenhas, M.; Garasia, S.; Johansson, M.A.; Ogden, N.H. Assessment of the probability of autochthonous transmission of chikungunya virus in canada under recent and projected climate change. Environ. Health Perspect. 2017, 125, 067001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pryor, J.W.H.; Irving, G.S.; Kundin, W.D.; Taylor, G.D.; Ziegler, R.F.; Dixon, J.D.F.; Hinkle, D.K. A serologic survey of military personnel and dogs in Thailand and South Vietnam for antibodies to Arboviruses, Rickettsia tsutsugamushi, and Pseudomonas pseudomallei. Am. J. Vet. Res. 1972, 33, 2091–2095. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, P.M.; Andreadis, T.G. Eastern equine encephalitis virus—Old enemy, new threat. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 1670–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Government of Canada. Risks of Japanese Encephalitis. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/diseases/japanese-encephalitis/risks-japanese-encephalitis.html (accessed on 29 May 2018).

- CFIA. Venezuelan Equine Encephalomyelitis (vee) Fact Sheet. Available online: http://www.inspection.gc.ca/animals/terrestrial-animals/diseases/reportable/venezuelan-equine-encephalomyelitis/fact-sheet/eng/1329841926239/1329842048136 (accessed on 29 May 2018).

- Forrester, N.L.; Wertheim, J.O.; Dugan, V.G.; Auguste, A.J.; Lin, D.; Adams, A.P.; Chen, R.; Gorchakov, R.; Leal, G.; Estrada-Franco, J.G.; et al. . Evolution and spread of Venezuelan equine encephalitis complex alphavirus in the Americas. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2017, 11, e0005693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Government of Canada. Risks of Tick-Borne Encephalitis (tbe). Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/diseases/tick-borne-encephalitis/risks-tick-borne-encephalitis.html (accessed on 29 May 2018).

- Mostashari, F.; Bunning, M.L.; Kitsutani, P.T.; Singer, D.A.; Nash, D.; Cooper, M.J.; Katz, N.; Liljebjelke, K.A.; Biggerstaff, B.J.; Fine, A.D.; et al. Epidemic West Nile encephalitis, New York, 1999: Results of a household-based seroepidemiological survey. Lancet 2001, 358, 261–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Canada. Surveillance of West Nile Virus. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/diseases/west-nile-virus/surveillance-west-nile-virus.html (accessed on 29 May 2018).

- Leighton, A.F.; Artsob, H.A.; Chu, M.C.; Olson, J.G. Serological survey of rural dogs and cats on the southwestern Canadian prairie for zoonotic pathogens. Can. J. Public Health 2001, 92, 67–71. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Government of Canada. List of Nationally Notifiable Diseases. Available online: http://diseases.canada.ca/notifiable/diseases-list (accessed on 29 May 2018).

- Paddock, C.D.; Brenner, O.; Vaid, C.; Boyd, D.B.; Berg, J.M.; Joseph, R.J.; Zaki, S.R.; Childs, J.E. Short report: Concurrent Rocky Mountain spotted fever in a dog and its owner. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2002, 66, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cockwill, K.R.; Taylor, S.M.; Snead, E.C.R.; Dickinson, R.; Cosford, K.; Malek, S.; Lindsay, L.R.; Diniz, P.P.V.D.P. Granulocytic anaplasmosis in three dogs from Saskatoon, Saskatchewan. Can. Vet. J. 2009, 50, 835–840. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shapiro, A.J.; Brown, G.; Norris, J.M.; Bosward, K.L.; Marriot, D.J.; Nandhakumar, B.; Breitschwerdt, E.B.; Malik, R. Vector-borne and zoonotic diseases of dogs in North-west New South Wales and the Northern Territory, Australia. BMC Vet. Res. 2017, 13, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leighton, P.A.; Koffi, J.K.; Pelcat, Y.; Lindsay, L.R.; Ogden, N.H. Predicting the speed of tick invasion: An empirical model of range expansion for the Lyme disease vector Ixodes scapularis in Canada. J. Appl. Ecol. 2012, 49, 457–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogden, N.H.; Lindsay, L.R.; Leighton, P.A. Predicting the rate of invasion of the agent of Lyme disease Borrelia burgdorferi. J. Appl. Ecol. 2013, 50, 510–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Canada. Risk of Lyme Disease to Canadians. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/diseases/lyme-disease/risk-lyme-disease.html (accessed on 29 May 2018).

- Ogden, N.H.; St-Onge, L.; Barker, I.K.; Brazeau, S.; Bigras-Poulin, M.; Charron, D.F.; Francis, C.M.; Heagy, A.; Lindsay, L.R.; Maarouf, A.; et al. Risk maps for range expansion of the Lyme disease vector, Ixodes scapularis, in Canada now and with climate change. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2008, 7, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mead, P.; Goel, R.; Kugeler, K. Canine serology as adjunct to human Lyme disease surveillance. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2011, 17, 1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamer, S.A.; Tsao, J.I.; Walker, E.D.; Mansfield, L.S.; Foster, E.S.; Hickling, G.J. Use of tick surveys and serosurveys to evaluate pet dogs as a sentinel species for emerging Lyme disease. Am. J. Vet. Res. 2009, 70, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Government of Canada. Surveillance of Lyme Disease. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/diseases/lyme-disease/surveillance-lyme-disease.html (accessed on 29 May 2018).

- CDC. Ehrlichiosis: Epidemiology and Statistics. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/ehrlichiosis/stats/index.html (accessed on 29 May 2018).

- Pritt, B.S.; Sloan, L.M.; Johnson, D.K.H.; Munderloh, U.G.; Paskewitz, S.M.; McElroy, K.M.; McFadden, J.D.; Binnicker, M.J.; Neitzel, D.F.; Liu, G.; et al. Emergence of a new pathogenic Ehrlichia species, Wisconsin and Minnesota, 2009. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 365, 422–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vieira, T.S.W.J.; da Costa Vieira, R.F.; do Nascimento, D.A.G.; Tamekuni, K.; dos Santos Toledo, R.; Chandrashekar, R.; Marcondes, M.; Biondo, A.W.; Vidotto, O. Serosurvey of tick-borne pathogens in dogs from urban and rural areas from Parana State, Brazil. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Vet. 2013, 22, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lauzi, S.; Maia, J.P.; Epis, S.; Marcos, R.; Pereira, C.; Luzzago, C.; Santos, M.; Puente-Payo, P.; Giordano, A.; Pajoro, M.; et al. Molecular detection of Anaplasma platys, Ehrlichia canis, Hepatozoon canis and Rickettsia monacensis in dogs from Maio Island of Cape Verde archipelago. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2016, 7, 964–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foley, J.E.; Foley, P.; Madigan, J.E. Spatial distribution of seropositivity to the causative agent of granulocytic ehrlichiosis in dogs in California. Am. J. Vet. Res. 2001, 62, 1599–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torgerson, P.R.; Devleesschauwer, B.; Praet, N.; Speybroeck, N.; Willingham, A.L.; Kasuga, F.; Rokni, M.B.; Zhou, X.N.; Fèvre, E.M.; Sripa, B.; et al. World Health Organization estimates of the global and regional disease burden of 11 foodborne parasitic diseases, 2010: A data synthesis. PLoS Med. 2015, 12, e1001920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dixon, B.R. Prevalence and control of toxoplasmosis—A Canadian perspective. Food Control 1992, 3, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CFIA. Annually Notifiable Diseases. Available online: http://www.inspection.gc.ca/animals/terrestrial-animals/diseases/annually-notifiable/eng/1305672292490/1305672713247 (accessed on 31 May 2018).

- Jenkins, E.J.; Simon, A.; Bachand, N.; Stephen, C. Wildlife parasites in a One Health World. Trends Parasitol. 2015, 31, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bullard, J.M.P.; Ahsanuddin, A.N.; Perry, A.M.; Lindsay, L.R.; Iranpour, M.; Dibernardo, A.; van Caeseele, P.G. The first case of locally acquired tick-borne Babesia microti infection in Canada. Can. J. Infect. Dis. Med. Microbiol. 2014, 25, e87. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Scott, J.D. First record of locally acquired human babesiosis in Canada caused by Babesia duncani: A case report. SAGE Open Med. Case Rep. 2017, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, S.F.; Delage, G.; Scalia, V.; Lindsay, R.; Bernier, F.; Dubuc, S.; Germain, M.; Pilot, G.; Yi, Q.L.; Fearon, M.A. Seroprevalence of Babesia microti infection in Canadian blood donors. Transfusion 2016, 56, 237–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klotins, K.C.; Martin, S.W.; Bonnett, B.N.; Peregrine, A.S. Canine heartworm testing in Canada: Are we being effective? Can. Vet. J. 2000, 41, 929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IDEXX. Real-Time Pet Disease Reporting. Available online: http://www.petdiseasereport.com/content/prevmap.aspx (accessed on 29 May 2018).

- CDC. Dirofilariasis Faqs. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/dirofilariasis/faqs.html (accessed on 29 May 2018).

- Theis, J.H. Public health aspects of dirofilariasis in the United States. Vet. Parasitol. 2005, 133, 157–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PHAC. Canada Communicable Disease Report: Locally Acquired Histoplasmosis Cluster, Alberta. 2003. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/reports-publications/canada-communicable-disease-report-ccdr/monthly-issue/2005-31/locally-acquired-histoplasmosis-cluster-alberta-2003.html (accessed on 29 May 2018).

- Sekhon, A.; Isaac-Renton, J.M.S.; Dixon, J.; Stein, L.; Sims, H. Review of human and animal cases of coccidioidomycosis diagnosed in Canada. Mycopathologia 1991, 113, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, R.; Revie, C.W.; Sanchez, J. The use of expert opinion to assess the risk of emergence or re-emergence of infectious diseases in Canada associated with climate change. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e41590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutton, A.J.; Duval, S.J.; Tweedie, R.L.; Abrams, K.R.; Jones, D.R. Empirical assessment of effect of publication bias on meta-analyses. BMJ 2000, 320, 1574–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dwan, K.; Altman, D.G.; Arnaiz, J.A.; Bloom, J.; Chan, A.-W.; Cronin, E.; Decullier, E.; Easterbrook, P.J.; Von Elm, E.; Gamble, C.; et al. Systematic review of the empirical evidence of study publication bias and outcome reporting bias (publication and reporting bias). PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e3081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fenwick, N.; Griffin, G.; Gauthier, C. Welfare of animals used in science: How the “three rs” ethic guides improvements. Can. Vet. J. 2009, 50, 523–530. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

| Term | Search Terms and Synonyms Used |

|---|---|

| dog | “dog*” OR “canine” OR “canis” |

| sentinel | “sentinel*” OR “indicator*” |

| disease | “public health” OR “infectious disease” OR “zoono*” OR “epidemiolog*” |

| Pathogen(s) Studied | Location | Populations | Conclusion | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B. burgdorferi | British Columbia; regions with previous tick infestation | Domestic owned dogs: healthy, post tick-bite or symptomatic for tick-borne disease | Value of randomly sampled, asymptomatic dogs as sentinels is limited. | [67] |

| Multiple; viral, bacterial, helminths, protozoa | British Columbia; remote coastal regions | Dogs owned by First Nations communities | Provides baseline results for future monitoring of infectious agents that could affect dogs, wildlife, and humans. | [57] |

| Arboviruses: West Nile virus (WNV), equine encephalitis virus (EEV), California serogroup viruses (CSGV) | Southern Quebec | Domestic owned dogs | Dogs provide sensitive indication of past or ongoing WNV or CSGV activity, and can indicate when transmission occurred. | [34] |

| Multiple; protozoa, helminths | Alberta and Northwest Territories | Dogs owned by First Nations communities | Dogs may serve as sources and sentinels for parasites in people and wildlife, and as parasite bridges between wildlife and humans. | [48] |

| Multiple; protozoa, helminths | Alberta and Saskatchewan | Dogs owned by First Nations communities | Companion-animal surveillance of parasites is a potential tool for detection of zoonotic risks for people, and could be used to evaluate efficacy of animal and public health interventions. | [66] |

| Multiple; bacteria, helminths, protozoa | Southeastern Saskatchewan | Dogs owned by First Nations communities | Emphasized the use of dogs as sentinels for emerging pathogens and the need for targeted surveillance and intervention programs within cultural communities. | [21] |

| Pathogen | Status in Canada | Suggested Region of Surveillance | Risk(s) Being Assessed | Suggested Dog Samples or Populations for Sentinel Surveillance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| California serogroup viruses | Considered to have high risk of emergence. Low prevalence currently, with vectors present. Not notifiable. 24 human cases confirmed in Canada in 2016. | Canada-wide | Emergence of pathogen. | Dogs of all ages for estimating period of former viral transmission. Juvenile dogs for detecting new periods of transmission. |

| Chikungunya virus | Low risk of emergence in one region, where climate change could enable establishment of the vector and virus for one to two months per year. Not notifiable. | Southern coastal British Columbia | Emergence of pathogen. | Outdoor dogs, preferably not receiving mosquito prophylaxis. |

| West Nile virus | Endemic in several regions of Canada with 104 human cases reported in 2016. Immediately notifiable; all laboratories must notify the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) when suspecting or diagnosing disease. | Southern Canada | Expansion, risk of infection, and predicting rise in human cases. | Outdoor, rural, or urban dogs, preferably not receiving mosquito prophylaxis. Juvenile dogs for detecting and predicting new viral transmission. Serum taken from annual parasite checks could be analyzed for WNV. |

| Rickettsia spp. | Present in western Canada. Not notifiable since 1978. | Western Canada | Geographic prevalence and expansion, risk of human infection, and individual risk based on health of in-contact dogs. | Rural dogs, ideally not taking tick prophylaxis, and on an individual-case level, dogs in-contact with clinically ill humans. |

| Lyme borreliosis | Endemic in multiple regions across Canada. Notifiable disease in people since 2009. | Canada-wide | Expansion of pathogen, risk of infection, presence of vector that might indicate other diseases. | Passive surveillance of submitted ticks could be supplemented by mandatory reporting of positive Lyme cases by laboratories to human health sector. |

| Ehrlichia spp. | Considered to be high risk for emergence, with new pathogenic species detected in Minnesota and Wisconsin. Not notifiable. | Southern Manitoba and southern Ontario | Emergence of pathogen. | Dogs not receiving tick prophylaxis (free-roaming, outdoors, stray, or relinquished dogs) and those with clinical signs of a history of tick bites. |

| Dirofilaria immitis | Low prevalence in dogs. Not notifiable. No reports of Canadian human cases, but disease documented in Wisconsin, Michigan, and New York State. | Southern Ontario and southern Quebec | Expansion of pathogen, increased risk of human infection. | Laboratory results from annual parasite screening could be shared with the human health sector. |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bowser, N.H.; Anderson, N.E. Dogs (Canis familiaris) as Sentinels for Human Infectious Disease and Application to Canadian Populations: A Systematic Review. Vet. Sci. 2018, 5, 83. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci5040083

Bowser NH, Anderson NE. Dogs (Canis familiaris) as Sentinels for Human Infectious Disease and Application to Canadian Populations: A Systematic Review. Veterinary Sciences. 2018; 5(4):83. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci5040083

Chicago/Turabian StyleBowser, Natasha H., and Neil E. Anderson. 2018. "Dogs (Canis familiaris) as Sentinels for Human Infectious Disease and Application to Canadian Populations: A Systematic Review" Veterinary Sciences 5, no. 4: 83. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci5040083

APA StyleBowser, N. H., & Anderson, N. E. (2018). Dogs (Canis familiaris) as Sentinels for Human Infectious Disease and Application to Canadian Populations: A Systematic Review. Veterinary Sciences, 5(4), 83. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci5040083