First Detection and Genetic Characterization of Influenza D Virus in Cattle in Spain

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Concerns

2.2. Samples

2.3. Nucleic Acid Extraction and Molecular Identification of Pathogens

2.4. Sequencing of Influenza D Hemagglutinin-Esterase (HEF) Gene

2.5. Statistical Analysis

2.6. Nucleotide Sequence Accession Numbers

3. Results

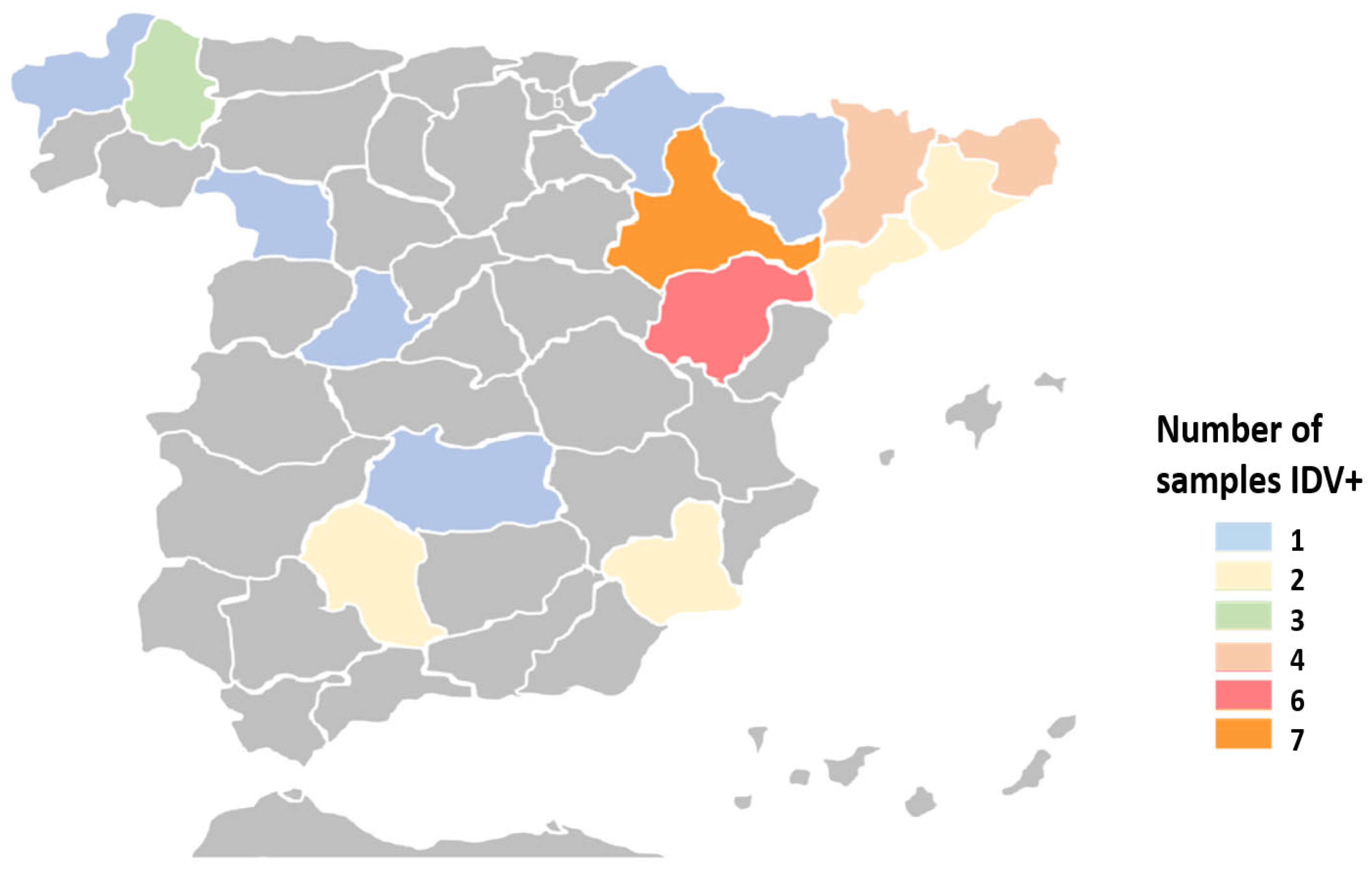

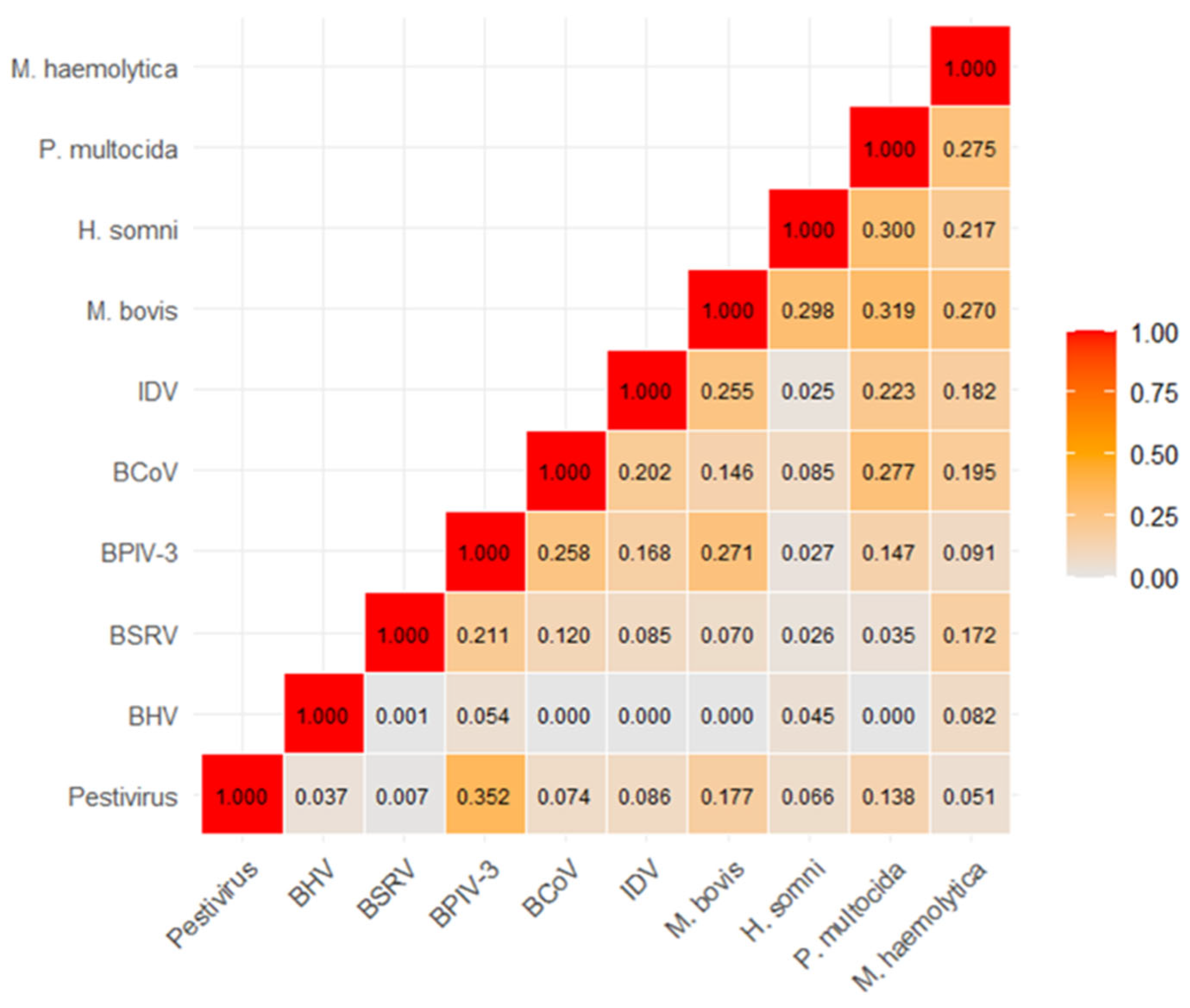

3.1. Detection of IDV and Other Pathogens in Cattle with Respiratory Clinical Signs

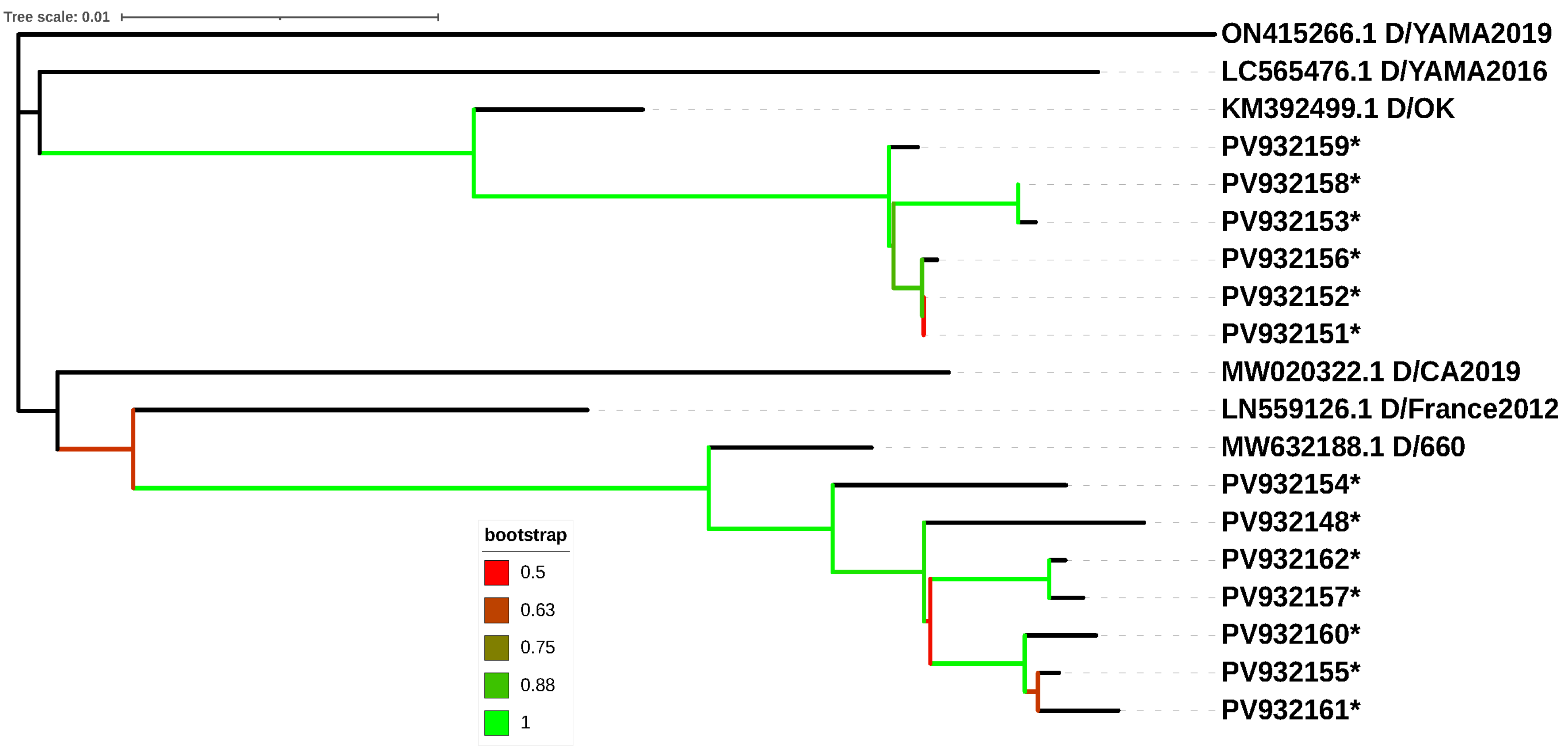

3.2. Sequencing and Phylogenetic Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, X.; Outlaw, C.; Olivier, A.K.; Woolums, A.; Epperson, W.; Wan, X.F. Pathogenesis of co-infections of influenza D virus and Mannheimia haemolytica in cattle. Vet. Microbiol. 2019, 231, 246–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pardon, B.; Callens, J.; Maris, J.; Allais, L.; Van Praet, W.; Deprez, P.; Ribbens, S. Pathogen-specific risk factors in acute outbreaks of respiratory disease in calves. J. Dairy Sci. 2020, 103, 2556–2566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fanelli, A.; Cirilli, M.; Lucente, M.S.; Zarea, A.A.K.; Buonavoglia, D.; Tempesta, M.; Greco, G. Fatal calf pneumonia outbreaks in Italian dairy herds involving Mycoplasma bovis and other agents of BRD complex. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 742785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hause, B.M.; Huntimer, L.; Falkenberg, S.; Henningson, J.; Lechtenberg, K.; Halbur, T. An inactivated influenza D virus vaccine partially protects cattle from respiratory disease caused by homologous challenge. Vet. Microbiol. 2017, 199, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blakebrough-Hall, C.; McMeniman, J.P.; González, L.A. An evaluation of the economic effects of bovine respiratory disease on animal performance, carcass traits, and economic outcomes in feedlot cattle defined using four BRD diagnosis methods. J. Anim. Sci. 2020, 98, skaa005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter-Smith, K.; Simpson, R. Insights into UK farmers’ attitudes towards cattle youngstock rearing and disease. Livestock 2020, 25, 274–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, K.K.; Pendell, D.L. Market Impacts of Reducing the Prevalence of Bovine Respiratory Disease in United States Beef Cattle Feedlots. Front. Vet. Sci. 2017, 4, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Li, F.; Wang, D. The first decade of research advances in influenza D virus. J. Gen. Virol. 2021, 102, jgv001529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Li, T.; Wen, Z.; Wu, S.; Wang, Z.; Zheng, J.; Chen, M.; Chen, F.; Wei, W.K.; Zhai, S.L.; et al. Identification of D/Yama2019 Lineage-Like Influenza D Virus in Chinese Cattle. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 939456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lion, A.; Secula, A.; Rançon, C.; Boulesteix, O.; Pinard, A.; Deslis, A.; Hägglund, S.; Salem, E.; Cassard, H.; Näslund, K.; et al. Enhanced Pathogenesis Caused by Influenza D Virus and Mycoplasma bovis Coinfection in Calves: A Disease Severity Linked with Overexpression of IFN-γ as a Key Player of the Enhanced Innate Immune Response in Lungs. Microbiol. Spectr. 2021, 9, e0169021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, M.; Puig, A.; Bassols, M.; Fraile, L.; Armengol, R. Influenza D Virus: A Review and Update of Its Role in Bovine Respiratory Syndrome. Viruses 2022, 14, 2717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limaye, S.; Lohar, T.; Dube, H.; Ramasamy, S.; Kale, M.; Kulkarni-Kale, U.; Kuchipudi, S.V. Rapid evolution leads to extensive genetic diversification of cattle flu Influenza D virus. Commun. Biol. 2024, 7, 1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudino, M.; Chiapponi, C.; Moreno, A.; Zohari, S.; O’Donovan, T.; Quinless, E.; Sausy, A.; Oliva, J.; Salem, E.; Fusade-Boyer, M.; et al. Evolutionary and temporal dynamics of emerging influenza D virus in Europe (2009–22). Virus Evol. 2022, 8, veac081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saegerman, C.; Gaudino, M.; Savard, C.; Broes, A.; Ariel, O.; Meyer, G.; Ducatez, M.F. Influenza D virus in respiratory disease in Canadian, province of Québec, cattle: Relative importance and evidence of new reassortment between different clades. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2022, 69, 1227–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murakami, S.; Sato, R.; Ishida, H.; Katayama, M.; Takenaka-Uema, A.; Horimoto, T. Influenza D Virus of New Phylogenetic Lineage, Japan. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020, 26, 168–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, E.H.; Lim, S.I.; Kim, M.J.; Kwon, M.; Kim, M.J.; Lee, K.B.; Choe, S.; An, D.J.; Hyun, B.H.; Park, J.Y.; et al. First Detection of Influenza D Virus Infection in Cattle and Pigs in the Republic of Korea. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, M.S.; Mosena, A.C.S.; Baumbach, L.; Demoliner, M.; Gularte, J.S.; Pavarini, S.P.; Driemeier, D.; Weber, M.N.; Spilki, F.R.; Canal, C.W. Cattle influenza D virus in Brazil is divergent from established lineages. Arch. Virol. 2022, 167, 1181–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yesilbag, K.; Toker, E.B.; Ates, O. Recent strains of influenza D virus create a new genetic cluster for European strains. Microb. Pathog. 2022, 172, 105769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ducatez, M.F.; Pelletier, C.; Meyer, G. Influenza D virus in cattle, France, 2011–2014. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2015, 21, 368–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snoeck, C.J.; Oliva, J.; Pauly, M.; Losch, S.; Wildschutz, F.; Muller, C.P.; Hübschen, J.M.; Ducatez, M.F. Influenza D Virus Circulation in Cattle and Swine, Luxembourg, 2012–2016. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2018, 24, 1388–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donovan, T.; Donohoe, L.; Ducatez, M.F.; Meyer, G.; Ryan, E. Seroprevalence of influenza D virus in selected sample groups of Irish cattle, sheep and pigs. Ir. Vet. J. 2019, 72, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliva, J.; Eichenbaum, A.; Belin, J.; Gaudino, M.; Guillotin, J.; Alzieu, J.P.; Nicollet, P.; Brugidou, R.; Gueneau, E.; Michel, E.; et al. Serological Evidence of Influenza D Virus Circulation Among Cattle and Small Ruminants in France. Viruses 2019, 11, 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falsini, A.; Coppola, C.; Fiori, A.; Buonavoglia, D.; Marchi, S.; Montomoli, E.; Pellegrini, F.; Lanave, G.; Martella, V.; Camero, M.; et al. Influenza D Virus Circulation Among Bovines, Swine, Equines, and Wild Boars in Italy: A Sero-Epidemiological Study. Pathogens 2025, 14, 891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dane, H.; Duffy, C.; Guelbenzu, M.; Hause, B.; Fee, S.; Forster, F.; McMenamy, M.J.; Lemon, K. Detection of influenza D virus in bovine respiratory disease samples, UK. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2019, 66, 2184–2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, O.; Gallagher, C.; Mooney, J.; Irvine, C.; Ducatez, M.; Hause, B.; McGrath, G.; Ryan, E. Influenza D Virus in Cattle, Ireland. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2018, 24, 389–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiapponi, C.; Faccini, S.; Fusaro, A.; Moreno, A.; Prosperi, A.; Merenda, M.; Baioni, L.; Gabbi, V.; Rosignoli, C.; Alborali, G.L.; et al. Detection of a New Genetic Cluster of Influenza D Virus in Italian Cattle. Viruses 2019, 11, 1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Studer, E.; Schönecker, L.; Meylan, M.; Stucki, D.; Dijkman, R.; Holwerda, M.; Glaus, A.; Becker, J. Prevalence of BRD-Related Viral Pathogens in the Upper Respiratory Tract of Swiss Veal Calves. Animals 2021, 11, 1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goecke, N.B.; Liang, Y.; Otten, N.D.; Hjulsager, C.K.; Larsen, L.E. Characterization of Influenza D Virus in Danish Calves. Viruses 2022, 14, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, I.; Banihashem, F.; Persson, A.; Hurri, E.; Kim, H.; Ducatez, M.; Geijer, E.; Valarcher, J.F.; Hägglund, S.; Zohari, S. Detection and Phylogenetic Characterization of Influenza D in Swedish Cattle. Viruses 2024, 17, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altschul, S.F.; Gish, W.; Miller, W.; Myers, E.W.; Lipman, D.J. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990, 215, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limaye, S.; Shelke, A.; Kale, M.M.; Kulkarni-Kale, U.; Kuchipudi, S.V. IDV Typer: An Automated Tool for Lineage Typing of Influenza D Viruses Based on Return Time Distribution. Viruses 2024, 16, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Kumar, S. MEGA11: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 3022–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Letunic, I.; Bork, P. Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL) v6: Recent updates to the phylogenetic tree display and annotation tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, W78–W82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rozas, J.; Ferrer-Mata, A.; Sánchez-DelBarrio, J.C.; Guirao-Rico, S.; Librado, P.; Ramos-Onsins, S.E.; Sánchez-Gracia, A. DnaSP v6: DNA sequence polymorphism Analysis of Large Datasets. Mol. Bio. Evol. 2017, 34, 3299–3302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asha, K.; Kumar, B. Emerging Influenza D Virus Threat: What We Know so Far! J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudino, M.; Moreno, A.; Snoeck, C.J.; Zohari, S.; Saegerman, C.; O’Donovan, T.; Ryan, E.; Zanni, I.; Foni, E.; Sausy, A.; et al. Emerging Influenza D virus infection in European livestock as determined in serology studies: Are we underestimating its spread over the continent? Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2021, 68, 1125–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudino, M.; Nagamine, B.; Ducatez, M.F.; Meyer, G. Understanding the mechanisms of viral and bacterial coinfections in bovine respiratory disease: A comprehensive literature review of experimental evidence. Vet. Res. 2022, 53, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Z.; Wang, J.; Tan, B.; Zhang, S.A. Systematic Study of Bovine Viral Diarrhoea Virus Co-Infection with Other Pathogens. Viruses 2025, 17, 700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal, J.M.C.; Fernández, A.; Arnal, J.L.; Baselga, C.; Benito Zuñiga, A.; Fernández-Garyzábal, J.F.; Alonso, A.I.V.; Cid, D. Cluster analysis of bovine respiratory disease (BRD)—Associated pathogens shows the existence of two epidemiological patterns in BRD outbreaks. Vet. Microbiol. 2023, 280, 109701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorin, S.; Richard, G.; Hervé, S.; Eveno, E.; Blanchard, Y.; Jardin, A.; Rose, N.; Simon, G. Characterization of Influenza D Virus Reassortant Strain in Swine from Mixed Pig and Beef Farm, France. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2024, 30, 1672–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, B.S.; Falkenberg, S.; Dassanayake, R.; Neill, J.; Velayudhan, B.; Li, F.; Vincent, A.L. Virus strain influenced the interspecies transmission of influenza D virus between calves and pigs. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2021, 68, 3396–3404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Positive Samples (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pathogen as Sole Agent | Infections with One or More Pathogens | Total | |

| IDV | 0 | 38 (12%) | 38 (12) |

| BCoV | 3 (0.9) | 92 (29.1) | 95 (30.1) |

| BHV-1 | 1 (0.3) | 9 (2.8) | 10 (0.3) |

| BRSV | 4 (1.3) | 52 (16.5) | 56 (17.7) |

| Pestivirus | 1 (0.3) | 32 (10.1) | 33 (10.4) |

| BPI3V | 1 (0.3) | 51 (16.1) | 52 (16.4) |

| H. somni | 0 | 86 (27.2) | 86 (27.2) |

| M. bovis | 15 (4.7) | 179 (56.6) | 194 (61.4) |

| M. haemolytica | 5 (1.6) | 120 (38) | 125 (39.5) |

| P. multocida | 9 (2.8) | 167 (52.8) | 176 (55.7) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Benito, A.A.; Monteagudo, L.V.; Lázaro-Gaspar, S.; Garza-Moreno, L.; Antón-Baltanás, N.; Quílez, J. First Detection and Genetic Characterization of Influenza D Virus in Cattle in Spain. Vet. Sci. 2026, 13, 130. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci13020130

Benito AA, Monteagudo LV, Lázaro-Gaspar S, Garza-Moreno L, Antón-Baltanás N, Quílez J. First Detection and Genetic Characterization of Influenza D Virus in Cattle in Spain. Veterinary Sciences. 2026; 13(2):130. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci13020130

Chicago/Turabian StyleBenito, Alfredo A., Luis V. Monteagudo, Sofía Lázaro-Gaspar, Laura Garza-Moreno, Nuria Antón-Baltanás, and Joaquín Quílez. 2026. "First Detection and Genetic Characterization of Influenza D Virus in Cattle in Spain" Veterinary Sciences 13, no. 2: 130. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci13020130

APA StyleBenito, A. A., Monteagudo, L. V., Lázaro-Gaspar, S., Garza-Moreno, L., Antón-Baltanás, N., & Quílez, J. (2026). First Detection and Genetic Characterization of Influenza D Virus in Cattle in Spain. Veterinary Sciences, 13(2), 130. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci13020130