Transmissible Gastroenteritis Virus Binding to Red Blood Cells Disrupts Iron Homeostasis and Promotes Viral Infection

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cells and Viruses

2.2. Animals Challenge

2.3. Blood Collection and Analysis

2.4. RNA Extraction and Reverse Transcription Quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) Assay

2.5. Plaque Assay

2.6. Flow Cytometry Analysis

2.7. Prussian Blue Staining

2.8. Diff-Quik Staining

2.9. Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM)

2.10. Osmotic Fragility Test

2.11. Phosphatidylserine (PS) Measurement

2.12. Raman Spectroscopy Analysis

2.13. Detection of Oxyhemoglobin and Methemoglobin

2.14. Western Blot (WB) Analysis

2.15. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Comparison of Hematological Parameters Between Healthy and TGEV-Infected Piglets

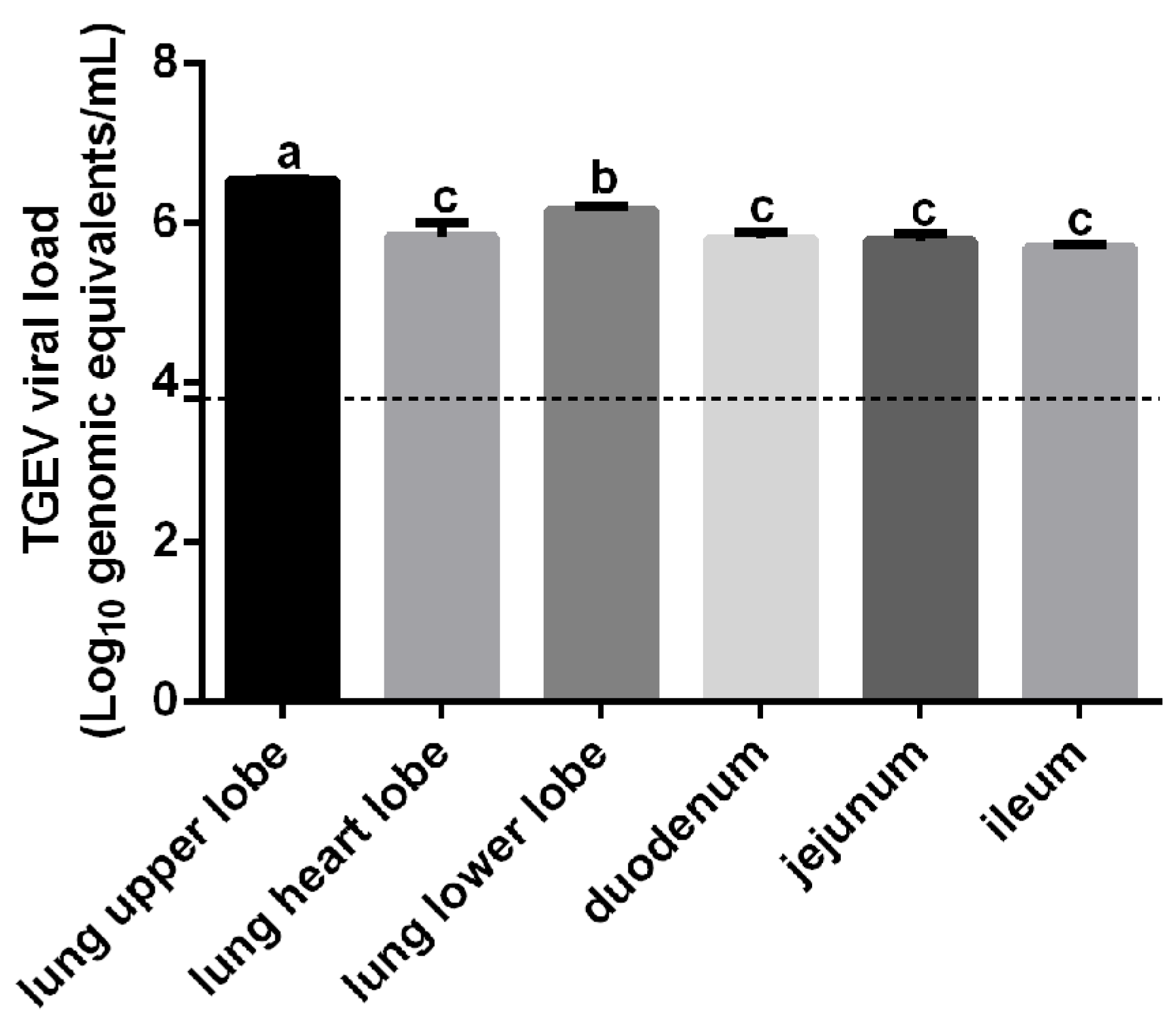

3.2. Detection of TGEV RNA in RBCs from Infected Piglets

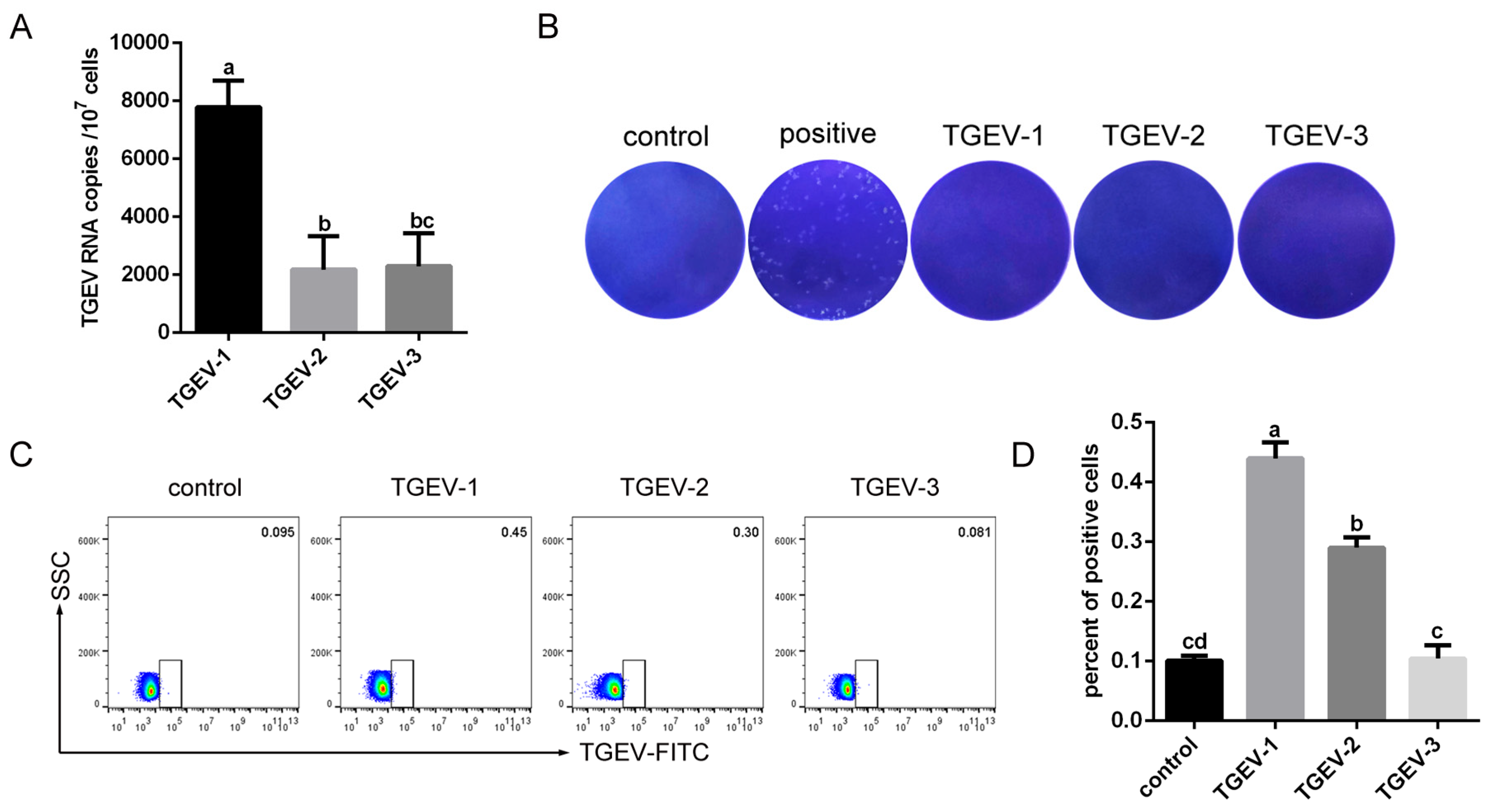

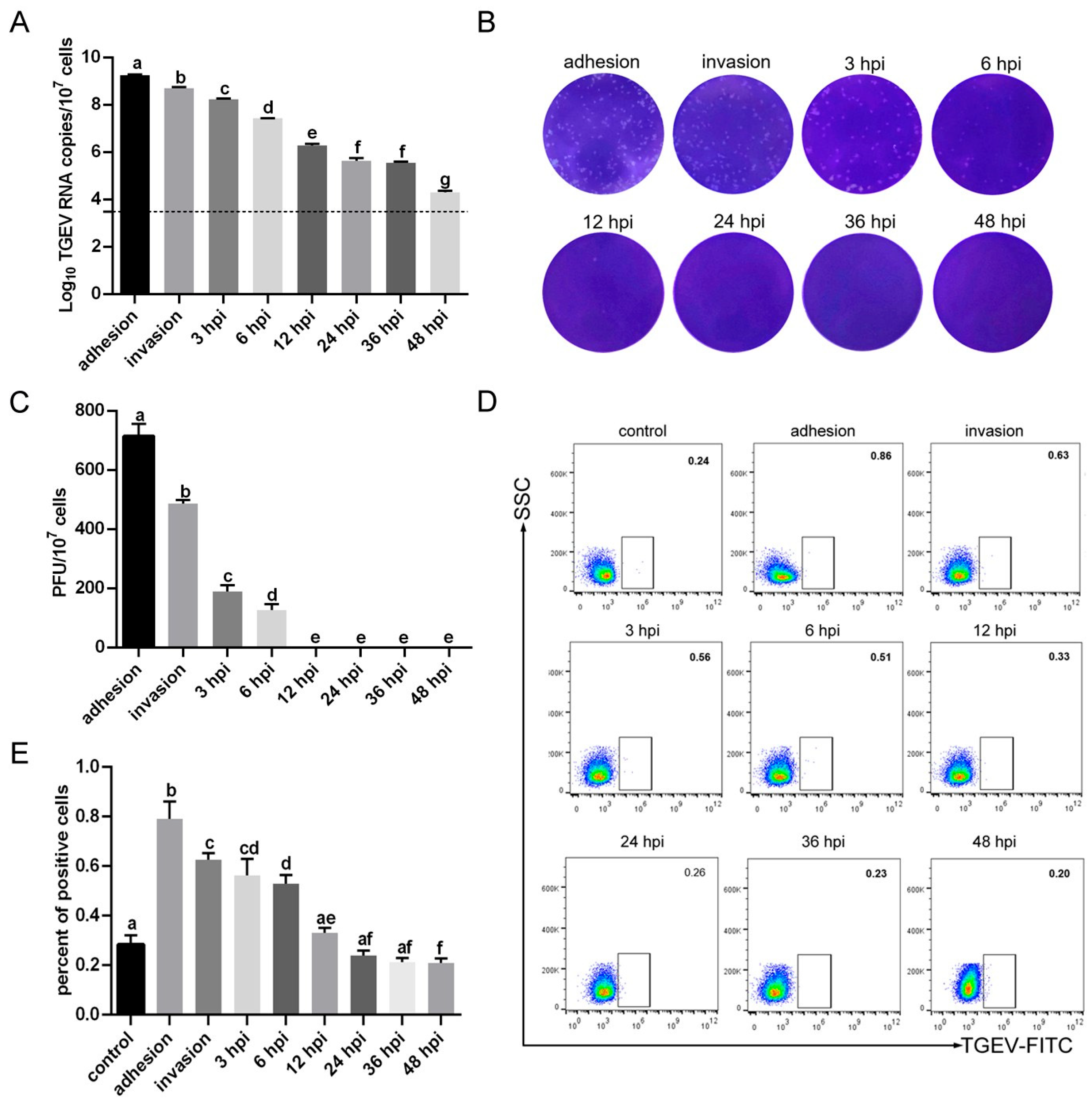

3.3. TGEV Binds to RBCs

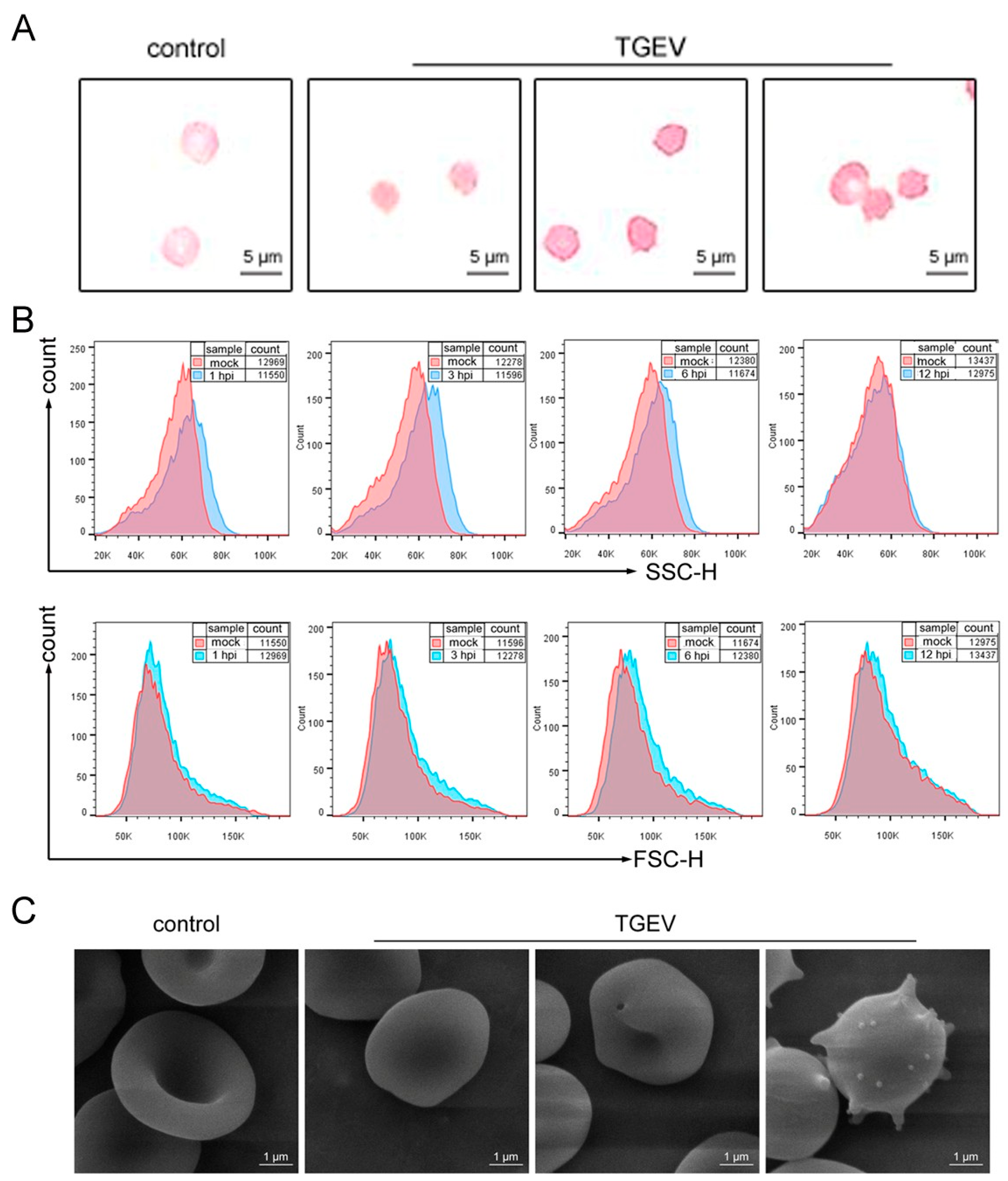

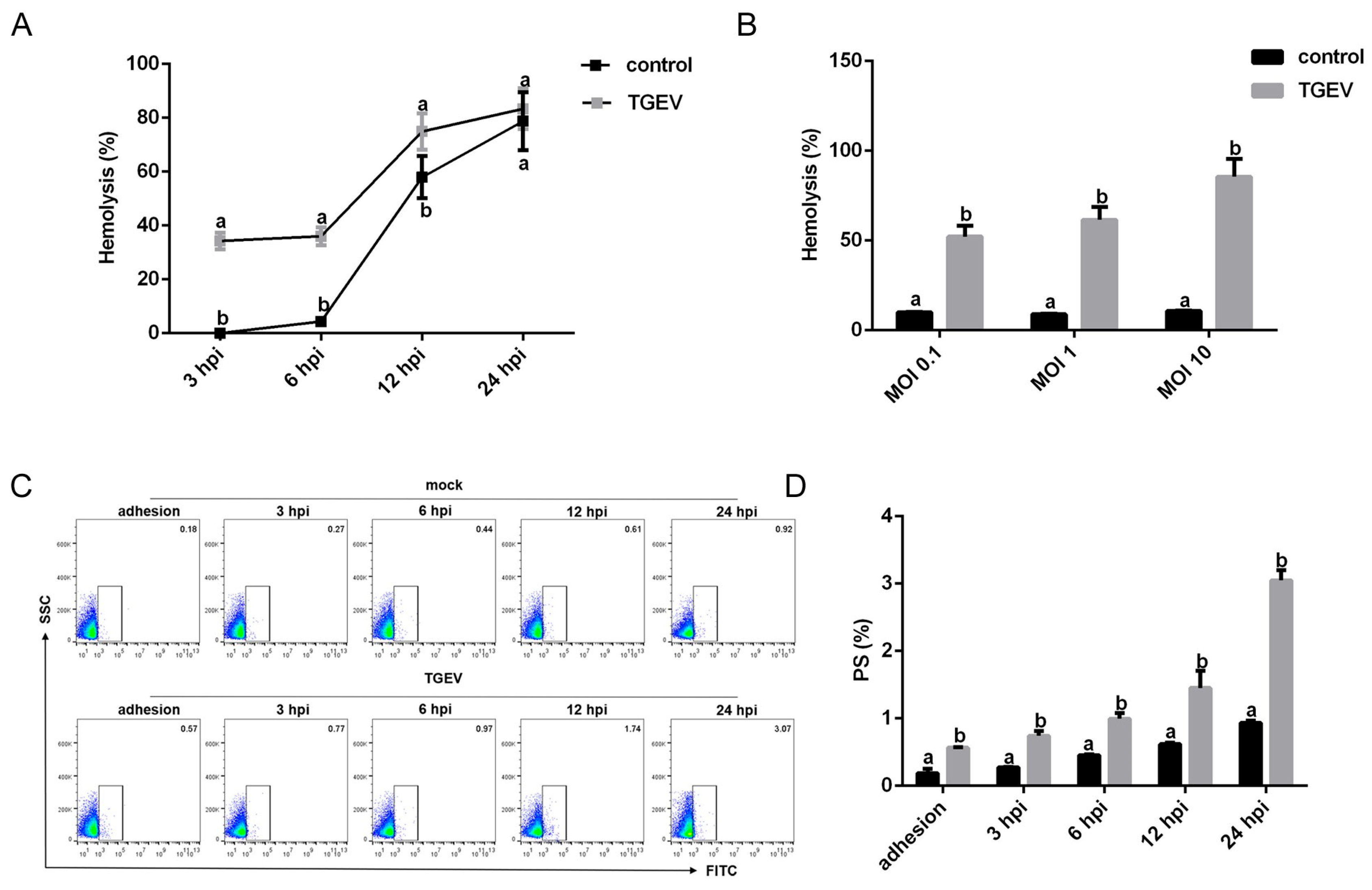

3.4. TGEV Binding Results in Structural Damage to RBCs

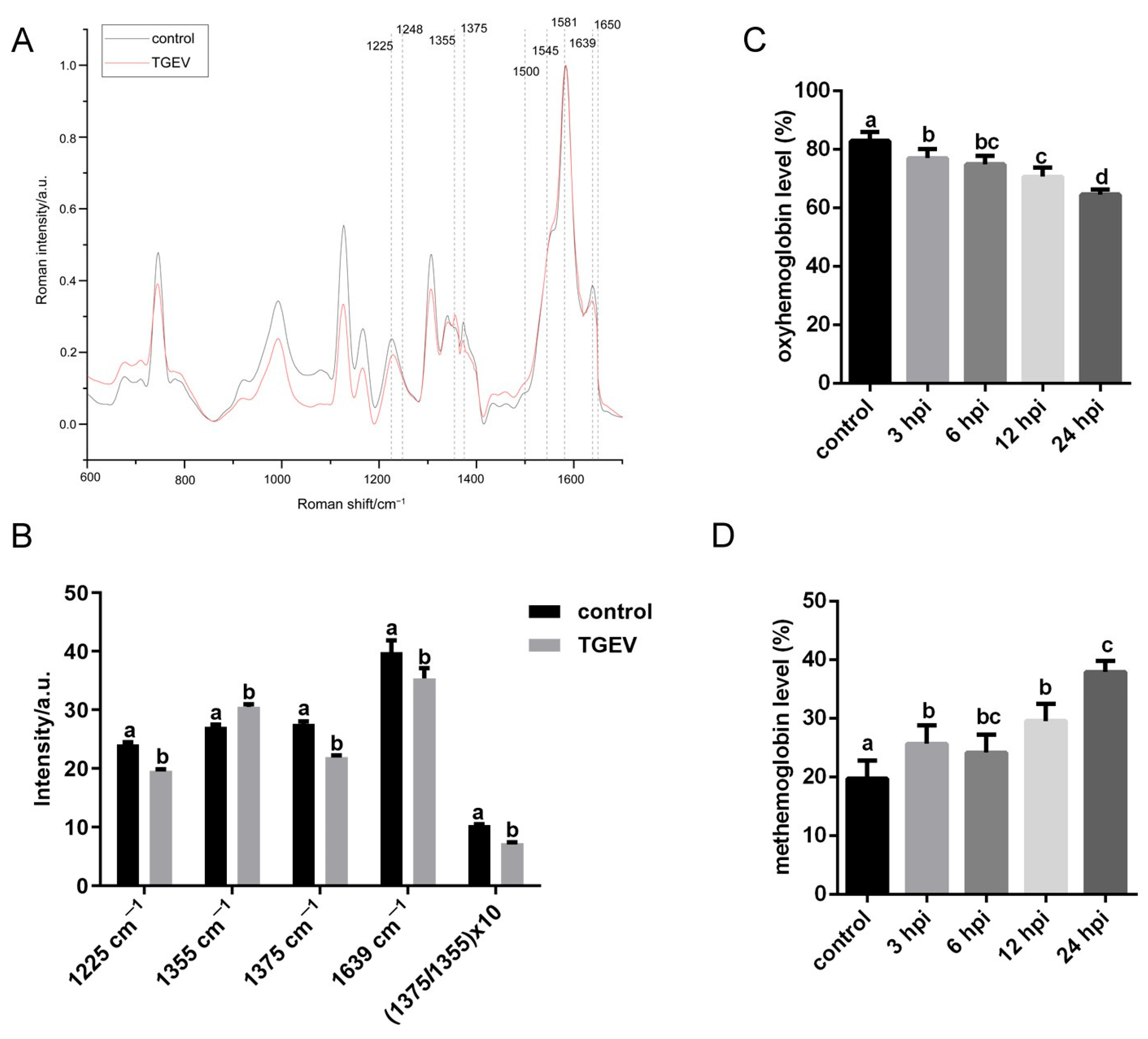

3.5. TGEV Decreases the Oxygen-Carrying Capacity of RBCs

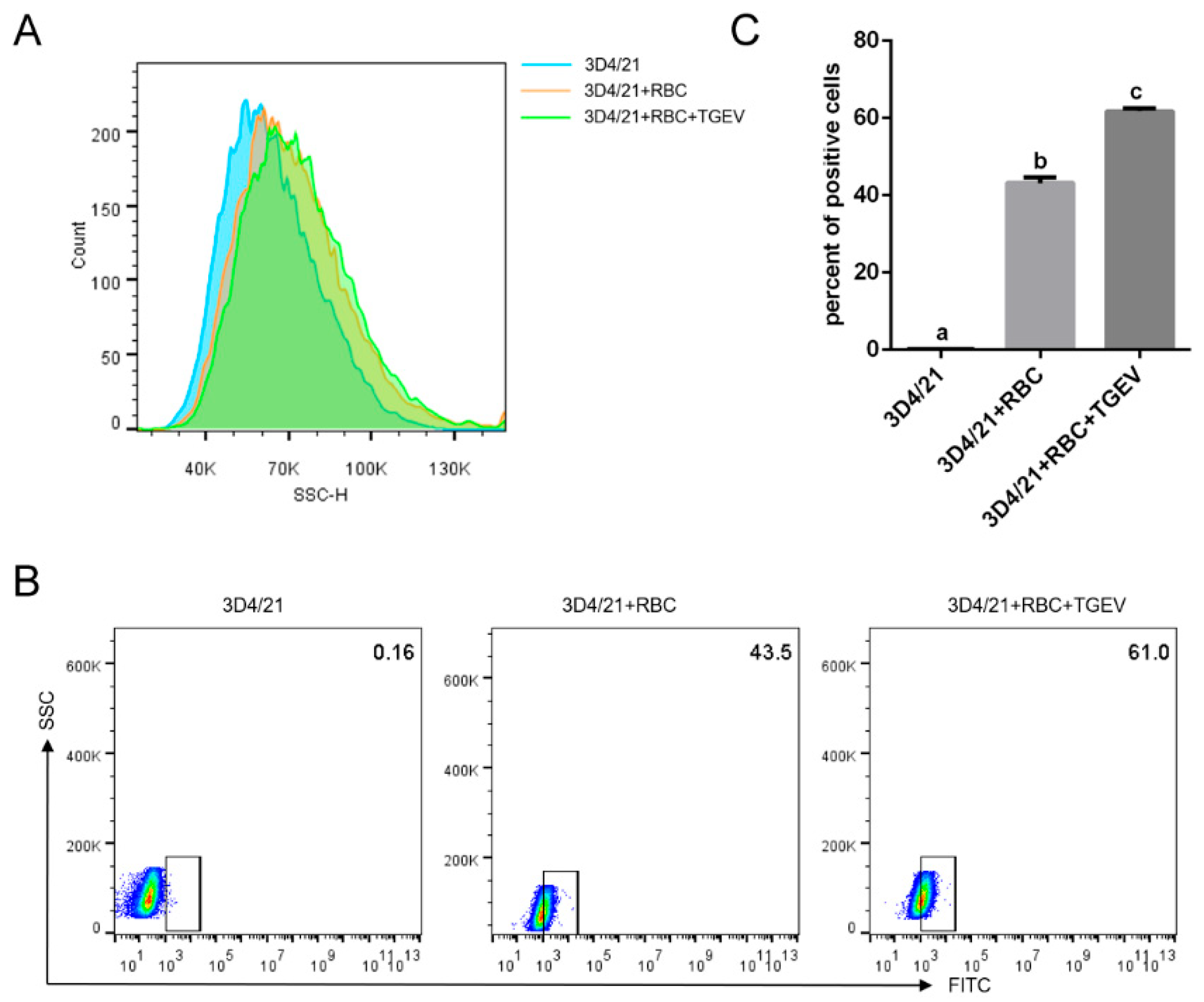

3.6. TGEV Binding Enhances Macrophage Phagocytosis of RBCs

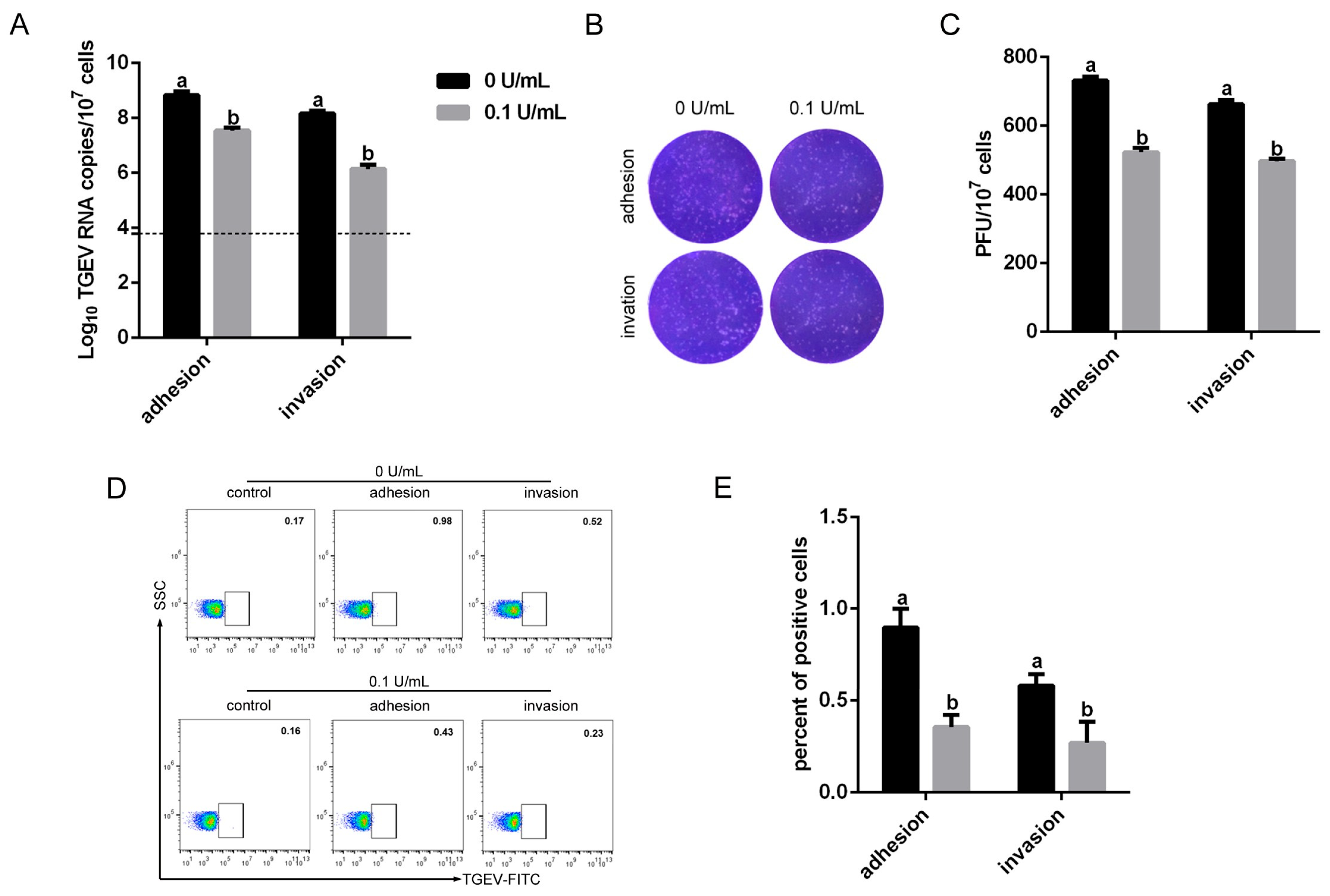

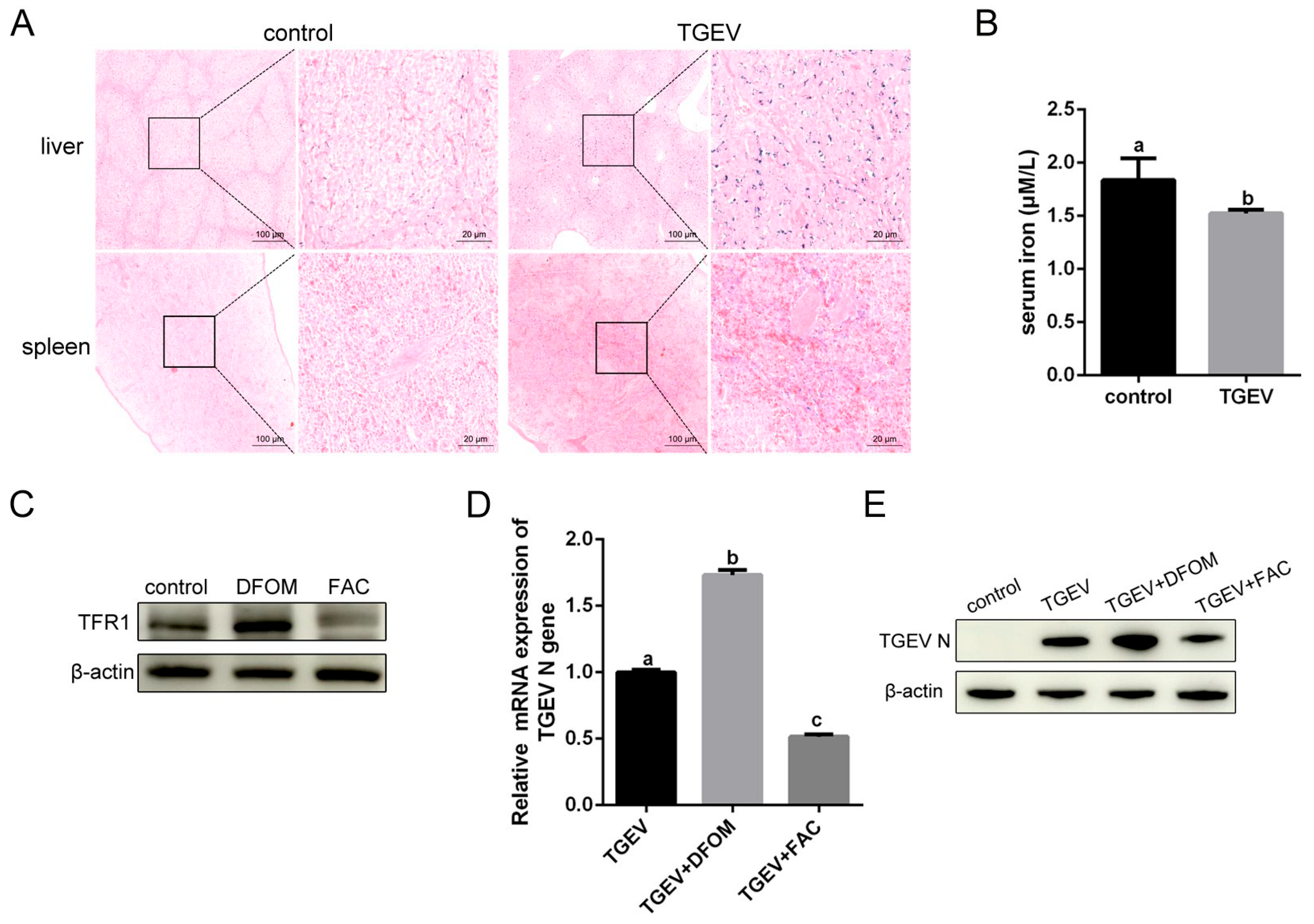

3.7. Iron Influence TGEV Infection

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhou, J.; Ma, L.; Li, J.; Yang, L.; Ouyang, H.; Yuan, H.; Pang, D. Transmissible Gastroenteritis Virus: An Update Review and Perspective. Viruses 2023, 15, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, F.; Knutson, T.P.; Rossow, S.; Saif, L.J.; Marthaler, D.G. Decline of transmissible gastroenteritis virus and its complex evolutionary relationship with porcine respiratory coronavirus in the United States. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 3953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Luo, S.; Gu, J.; Li, Z.; Li, K.; Yuan, W.; Ye, Y.; Li, H.; Ding, Z.; Song, D.; et al. Prevalence and phylogenetic analysis of porcine diarrhea associated viruses in southern China from 2012 to 2018. BMC Vet. Res. 2019, 15, 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, L.; Dai, H.B.; Luo, Z.P.; Zhu, L.; Zhao, J.; Lee, F.Q.; Liu, Z.Y.; Nie, M.C.; Wang, X.T.; Zhou, Y.C.; et al. Characterization and Evaluation of the Pathogenicity of a Natural Gene-Deleted Transmissible Gastroenteritis Virus in China. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2023, 2023, 2652850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, L.K.M.; Dobkin, J.; Eckart, K.A.; Gereg, I.; DiSalvo, A.; Nolder, A.; Anis, E.; Ellis, J.C.; Turner, G.; Mangalmurti, N.S. Bat Red Blood Cells Express Nucleic Acid-Sensing Receptors and Bind RNA and DNA. Immunohorizons 2022, 6, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, L.K.M.; Murphy, S.; Kokkinaki, D.; Venosa, A.; Sherrill-Mix, S.; Casu, C.; Rivella, S.; Weiner, A.; Park, J.; Shin, S.; et al. DNA binding to TLR9 expressed by red blood cells promotes innate immune activation and anemia. Sci. Transl. Med. 2021, 13, eabj1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, E.; Falk, A.B. Erythrocytes as Biomarkers of Virus and Bacteria in View of Metal Ion Homeostasis. In Erythrocyte—A Peripheral Biomarker for Infection and Inflammation; Fatima-Shad, K., Ed.; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, L.; Huang, Y.; Dai, M.; Zhao, X.; Du, Q.; Dong, F.; Wang, L.; Huo, R.; Zhang, W.; Xu, X.; et al. Transmissible gastroenteritis virus infection induces cell cycle arrest at S and G2/M phases via p53-dependent pathway. Virus Res. 2013, 178, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, P.; Du, E.Z.; Luo, W.T.; Yang, Y.L.; Zhang, Y.Q.; Wang, B.; Huang, Y.W. Characteristics of the Life Cycle of Porcine Deltacoronavirus (PDCoV) In Vitro: Replication Kinetics, Cellular Ultrastructure and Virion Morphology, and Evidence of Inducing Autophagy. Viruses 2019, 11, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Hu, W.; Yuan, L.; Yang, Q. Transferrin receptor 1 is a supplementary receptor that assists transmissible gastroenteritis virus entry into porcine intestinal epithelium. Cell Commun. Signal 2018, 16, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, J.L.; Mellors, J.W. Detection of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) RNA in Blood of Patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): What Does It Mean? Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 73, e2898–e2900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madson, D.M.; Arruda, P.H.; Magstadt, D.R.; Burrough, E.R.; Hoang, H.; Sun, D.; Bower, L.P.; Bhandari, M.; Gauger, P.C.; Stevenson, G.W.; et al. Characterization of Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus Isolate US/Iowa/18984/2013 Infection in 1-Day-Old Cesarean-Derived Colostrum-Deprived Piglets. Vet. Pathol. 2016, 53, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lednicky, J.A.; Tagliamonte, M.S.; White, S.K.; Elbadry, M.A.; Alam, M.M.; Stephenson, C.J.; Bonny, T.S.; Loeb, J.C.; Telisma, T.; Chavannes, S.; et al. Independent infections of porcine deltacoronavirus among Haitian children. Nature 2021, 600, 133–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, T.; Shibahara, T.; Imai, N.; Yamamoto, T.; Ohashi, S. Genetic characterization and pathogenicity of Japanese porcine deltacoronavirus. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2018, 61, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, K.; Hu, H.; Saif, L.J. Porcine deltacoronavirus infection: Etiology, cell culture for virus isolation and propagation, molecular epidemiology and pathogenesis. Virus Res. 2016, 226, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yuan, C.; Liu, P.; Li, Y.; Zhang, P.; Yang, Q. Red blood cells serve as a vehicle for PEDV transmission. Vet. Microbiol. 2021, 257, 109081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagman, K.; Postigo, T.; Diez-Castro, D.; Ursing, J.; Bermejo-Martin, J.F.; de la Fuente, A.; Tedim, A.P. Prevalence and clinical relevance of viraemia in viral respiratory tract infections: A systematic review. Lancet Microbe 2025, 6, 100967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagman, K.; Hedenstierna, M.; Rudling, J.; Gille-Johnson, P.; Hammas, B.; Grabbe, M.; Jakobsson, J.; Dillner, J.; Ursing, J. Duration of SARS-CoV-2 viremia and its correlation to mortality and inflammatory parameters in patients hospitalized for COVID-19: A cohort study. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2022, 102, 115595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, J.L.; Bain, W.; Naqvi, A.; Staines, B.; Castanha, P.M.S.; Yang, H.; Boltz, V.F.; Barratt-Boyes, S.; Marques, E.T.A.; Mitchell, S.L.; et al. Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Viremia Is Associated with Coronavirus Disease 2019 Severity and Predicts Clinical Outcomes. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 74, 1525–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olech, M.; Antas, M. Transmissible Gastroenteritis Virus (TGEV) and Porcine Respiratory Coronavirus (PRCV): Epidemiology and Molecular Characteristics—An Updated Overview. Viruses 2025, 17, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Zu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, F.; Jin, X.; Hu, H. Porcine Deltacoronavirus Utilizes Sialic Acid as an Attachment Receptor and Trypsin Can Influence the Binding Activity. Viruses 2021, 13, 2442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheim, D.E. A Deadly Embrace: Hemagglutination Mediated by SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein at Its 22 N-Glycosylation Sites, Red Blood Cell Surface Sialoglycoproteins, and Antibody. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, F.; Connes, P. Morphology and Function of Red Blood Cells in COVID-19 Patients: Current Overview 2023. Life 2024, 14, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, A.; Tellone, E.; Barreca, D.; Ficarra, S.; Laganà, G. Implication of COVID-19 on Erythrocytes Functionality: Red Blood Cell Biochemical Implications and Morpho-Functional Aspects. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asher, D.R.; Cerny, A.M.; Finberg, R.W. The erythrocyte viral trap: Transgenic expression of viral receptor on erythrocytes attenuates coxsackievirus B infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 12897–12902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, M.A.G.; Kieffer, C.; Bjorkman, P.J. In vitro characterization of engineered red blood cells as viral traps against HIV-1 and SARS-CoV-2. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2021, 21, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, T.; Stefanoni, D.; Dzieciatkowska, M.; Issaian, A.; Nemkov, T.; Hill, R.C.; Francis, R.O.; Hudson, K.E.; Buehler, P.W.; Zimring, J.C.; et al. Evidence of Structural Protein Damage and Membrane Lipid Remodeling in Red Blood Cells from COVID-19 Patients. J. Proteome Res. 2020, 19, 4455–4469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Alessandro, A.; Krisnevskaya, E.; Leguizamon, V.; Hernández, I.; de la Torre, C.; Bech, J.-J.; Navarro, J.-T.; Vives-Corrons, J.-L. SARS-CoV-2 Infection and Anemia—A Focus on RBC Deformability and Membrane Proteomics—Integrated Observational Prospective Study. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kronstein-Wiedemann, R.; Stadtmüller, M.; Traikov, S.; Georgi, M.; Teichert, M.; Yosef, H.; Wallenborn, J.; Karl, A.; Schütze, K.; Wagner, M.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Infects Red Blood Cell Progenitors and Dysregulates Hemoglobin and Iron Metabolism. Stem Cell Rev. Rep. 2022, 18, 1809–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechuga, G.C.; Souza-Silva, F.; Sacramento, C.Q.; Trugilho, M.R.O.; Valente, R.H.; Napoleão-Pêgo, P.; Dias, S.S.G.; Fintelman-Rodrigues, N.; Temerozo, J.R.; Carels, N.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Proteins Bind to Hemoglobin and Its Metabolites. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchla, A.; Kriebardis, A.G.; Georgatzakou, H.T.; Fortis, S.P.; Thomopoulos, T.P.; Lekkakou, L.; Markakis, K.; Gkotzias, D.; Panagiotou, A.; Papageorgiou, E.G.; et al. Red Blood Cell Abnormalities as the Mirror of SARS-CoV-2 Disease Severity: A Pilot Study. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 825055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grau, M.; Ibershoff, L.; Zacher, J.; Bros, J.; Tomschi, F.; Diebold, K.F.; Predel, H.G.; Bloch, W. Even patients with mild COVID-19 symptoms after SARS-CoV-2 infection show prolonged altered red blood cell morphology and rheological parameters. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2022, 26, 3022–3030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klei, T.R.; Meinderts, S.M.; van den Berg, T.K.; van Bruggen, R. From the Cradle to the Grave: The Role of Macrophages in Erythropoiesis and Erythrophagocytosis. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borges, M.D.; Sesti-Costa, R. Macrophages: Key players in erythrocyte turnover. Hematol. Transfus. Cell Ther. 2022, 44, 574–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, S.; Ge, H.; Li, S.; Qiu, H.-J. Modulation of Macrophage Polarization by Viruses: Turning Off/On Host Antiviral Responses. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 839585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, F.; Xu, Z.; Gao, P.; Qu, Y.; Ge, X.; Zhang, Y.; Han, J.; Guo, X.; Zhou, L.; Yang, H. African swine fever virus infection enhances CD14-dependent phagocytosis of porcine alveolar macrophages to promote bacterial uptake and apoptotic body-mediated viral transmission. J. Virol. 2025, 99, e0069025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Li, Z.; Niu, J.; Xu, Y.; Ma, L.; Lu, A.; Wang, X.; Qian, Z.; Huang, Z.; Jin, X.; et al. Antiviral effects of ferric ammonium citrate. Cell Discov. 2018, 4, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Z.; Wang, C.; Tang, X.; Yang, M.; Duan, Z.; Liu, L.; Lu, S.; Ma, L.; Cheng, R.; Wang, G.; et al. Human transferrin receptor can mediate SARS-CoV-2 infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2317026121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazel-Sanchez, B.; Niu, C.; Williams, N.; Bachmann, M.; Choltus, H.; Silva, F.; Serre-Beinier, V.; Karenovics, W.; Iwaszkiewicz, J.; Zoete, V.; et al. Influenza A virus exploits transferrin receptor recycling to enter host cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2214936120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Cao, Y.; Yang, Q. Transferrin receptor 1 levels at the cell surface influence the susceptibility of newborn piglets to PEDV infection. PLoS Pathog. 2020, 16, e1008682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Tong, L.; Nie, K.; Wiwatanaratanabutr, I.; Sun, P.; Li, Q.; Yu, X.; Wu, P.; Wu, T.; Yu, C.; et al. Host serum iron modulates dengue virus acquisition by mosquitoes. Nat. Microbiol. 2019, 4, 2405–2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esan, M.O.; van Hensbroek, M.B.; Nkhoma, E.; Musicha, C.; White, S.A.; Ter Kuile, F.O.; Phiri, K.S. Iron supplementation in HIV-infected Malawian children with anemia: A double-blind, randomized, controlled trial. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2013, 57, 1626–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Peak Position (cm−1) | Assignment |

|---|---|

| 1225 | protein |

| 1248 | Amide III/heme aggregation |

| 1355 | Fe2+/deoxyHb |

| 1375 | Fe3+/oxyHb |

| 1565 | tryptophan |

| 1585 | cytochrome c |

| 1639 | hemoglobin |

| 1650 | Amide I |

| Blood Parameters | Unit | Control | TGEV |

|---|---|---|---|

| RBC | 1012/L | 6.477 ± 3.059 | 4.277 ± 1.767 |

| HGB | g/L | 116.3 ± 51.87 | 78.33 ± 32.72 |

| HCT | % | 38.43 ± 17.25 | 24.27 ± 9.765 |

| MCV | fL | 59.97 ± 1.234 | 57.13 ± 5.297 |

| MCH | pg | 18.1 ± 0.4359 | 18.37 ± 2.996 |

| MCHC | g/L | 302.3 ± 3.215 | 321 ± 21.63 |

| RDW_CV | % | 27.7 ± 3.503 a | 19.73 ± 1.358 b |

| RDW_SD | fL | 50.57 ± 2.829 a | 38.13 ± 2.779 b |

| PLT | 109/L | 889 ± 426.9 | 596 ± 369.9 |

| MPV | fL | 12.17 ± 3.753 | 10 ± 0.7 |

| PDW | % | 14.93 ± 0.5033 | 14.63 ± 0.6658 |

| PCT | % | 0.2473 ± 0.1426 | 0.1603 ± 0.007506 |

| pH | 7.265 ± 0.1526 | 7.237 ± 0.1617 | |

| O2 | mmHg | 51.33 ± 8.622 | 50.67 ± 4.041 |

| CO2 | mmHg | 35.33 ± 2.887 a | 42.33 ± 2.887 b |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Xia, L.; Wang, Z.; He, Y.; Wang, J.; Ren, J.; Zhang, E.; Liu, Z.; Li, Y.; Li, Z.; Wei, Z. Transmissible Gastroenteritis Virus Binding to Red Blood Cells Disrupts Iron Homeostasis and Promotes Viral Infection. Vet. Sci. 2026, 13, 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci13010042

Xia L, Wang Z, He Y, Wang J, Ren J, Zhang E, Liu Z, Li Y, Li Z, Wei Z. Transmissible Gastroenteritis Virus Binding to Red Blood Cells Disrupts Iron Homeostasis and Promotes Viral Infection. Veterinary Sciences. 2026; 13(1):42. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci13010042

Chicago/Turabian StyleXia, Lu, Ziqi Wang, Yeqing He, Jingwen Wang, Junyuan Ren, Erhao Zhang, Zhonghu Liu, Yilei Li, Zi Li, and Zhanyong Wei. 2026. "Transmissible Gastroenteritis Virus Binding to Red Blood Cells Disrupts Iron Homeostasis and Promotes Viral Infection" Veterinary Sciences 13, no. 1: 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci13010042

APA StyleXia, L., Wang, Z., He, Y., Wang, J., Ren, J., Zhang, E., Liu, Z., Li, Y., Li, Z., & Wei, Z. (2026). Transmissible Gastroenteritis Virus Binding to Red Blood Cells Disrupts Iron Homeostasis and Promotes Viral Infection. Veterinary Sciences, 13(1), 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci13010042