Owners’ Experience and Satisfaction with Radioiodine Treatment in Hyperthyroid Cats—A Prospective Questionnaire Study

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

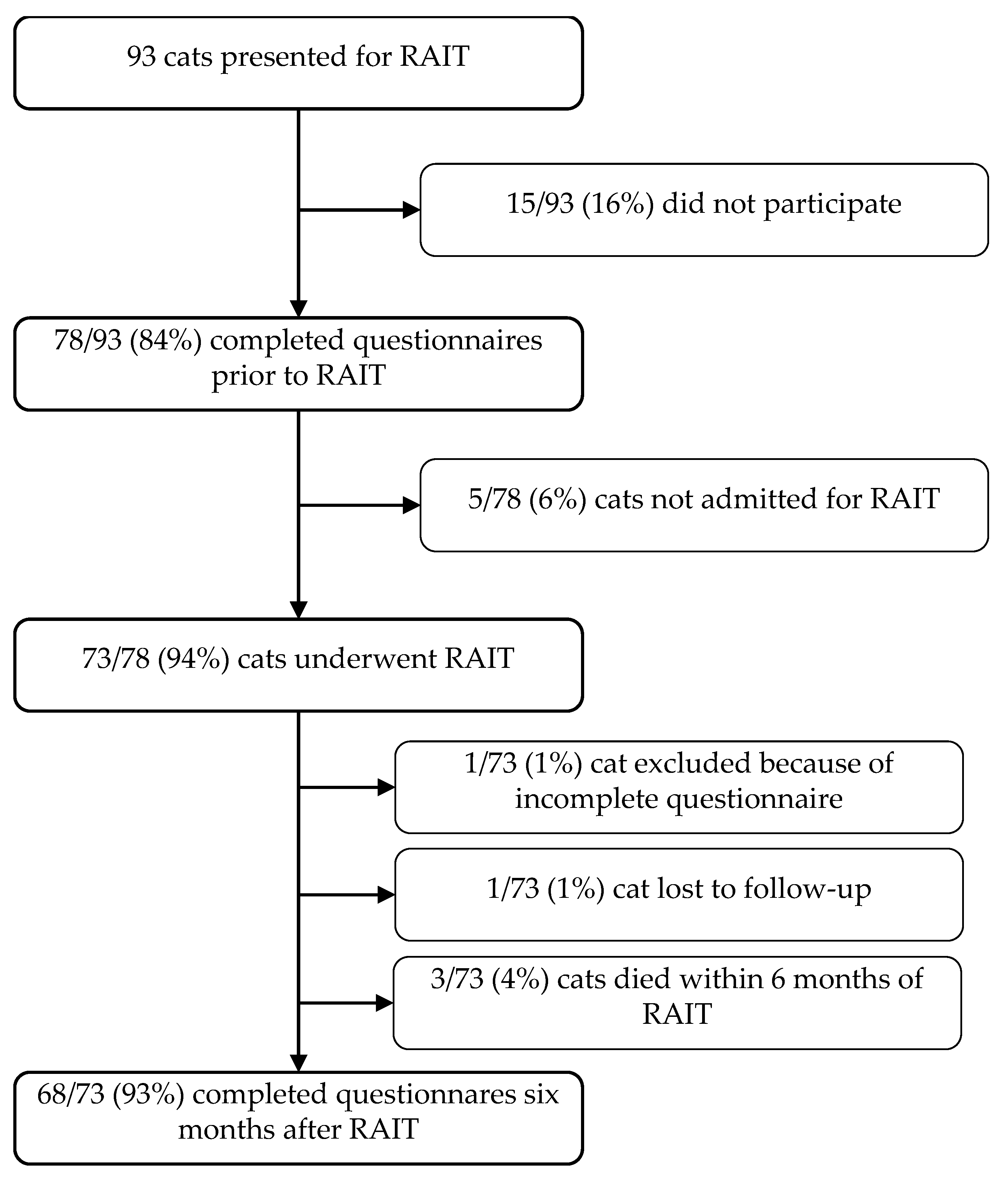

2.1. Study Design

2.1.1. Standard Procedures Before, During, and After RAIT at the Clinic for Small Animals and Radiation Safety Measures for Owners

2.1.2. Hyperthyroidism Cat-QoL

2.1.3. Questions Prior to RAIT

2.1.4. Questions Six Months After RAIT

2.1.5. Evaluation of Treatment Outcome 6 Months Post-RAIT

2.2. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Owners of RAI-Treated Cats

3.2. Characteristics of the Cats Presented for RAIT

3.3. General Data Relating to the Decision of the Owner in Favour of a RAIT

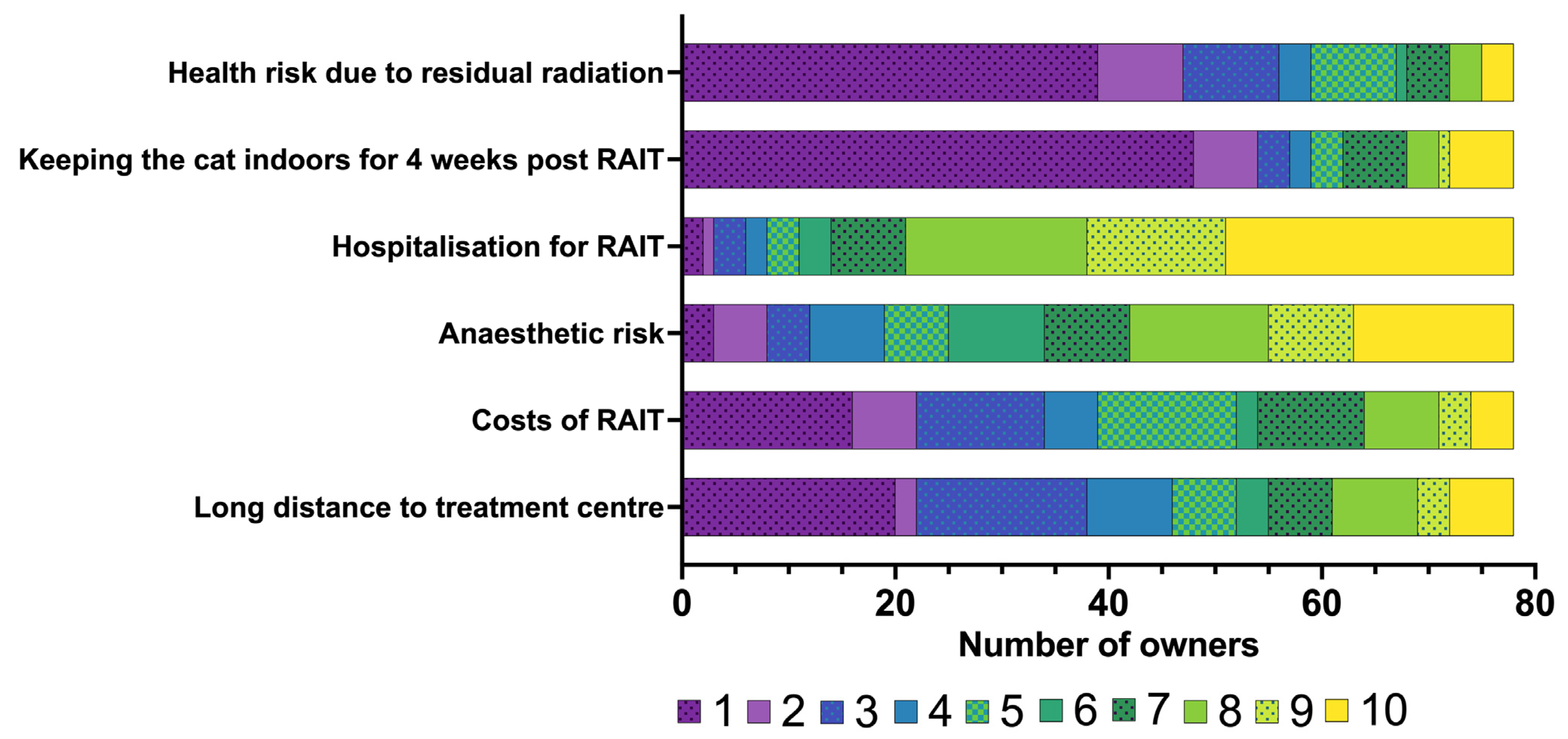

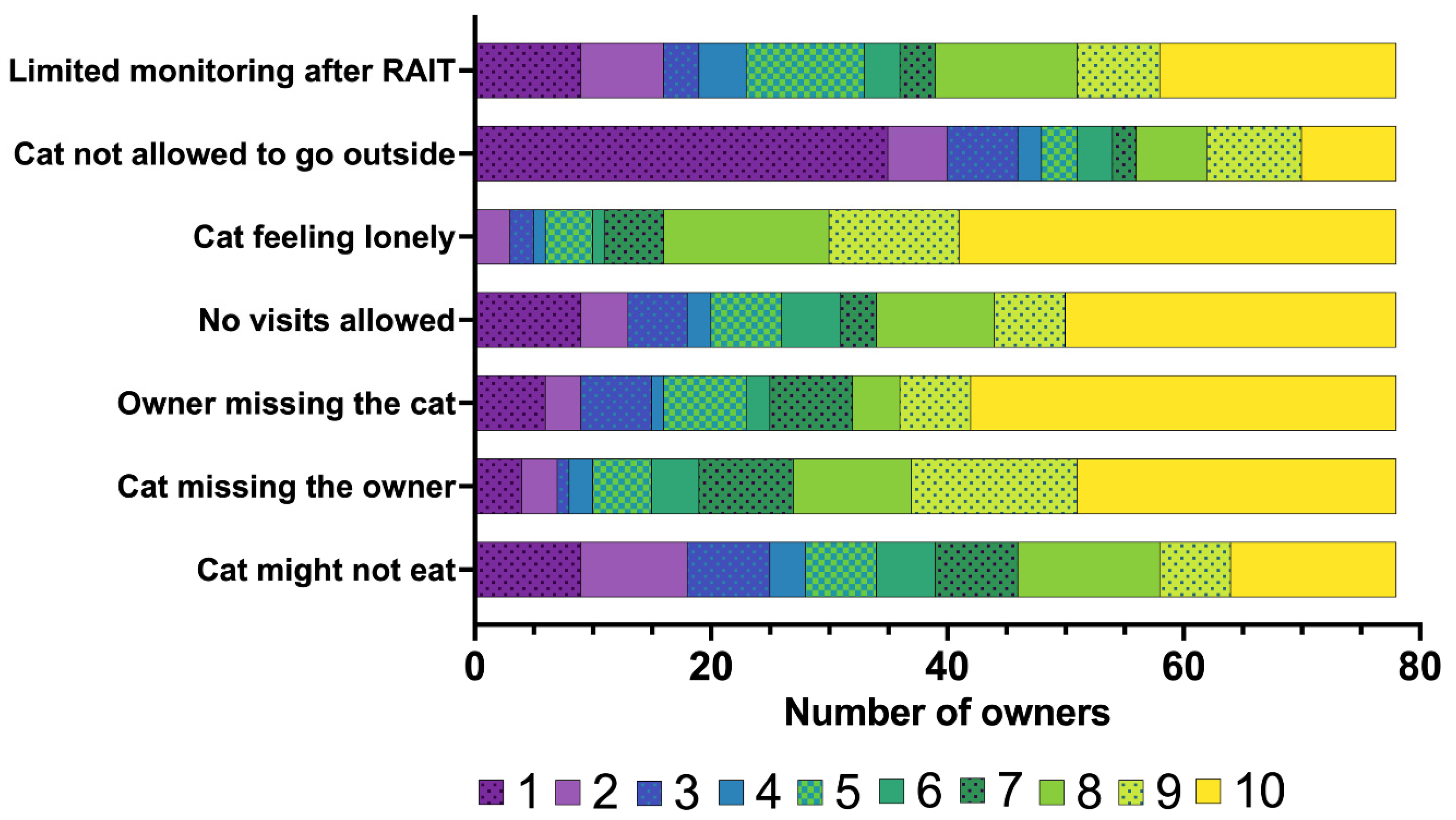

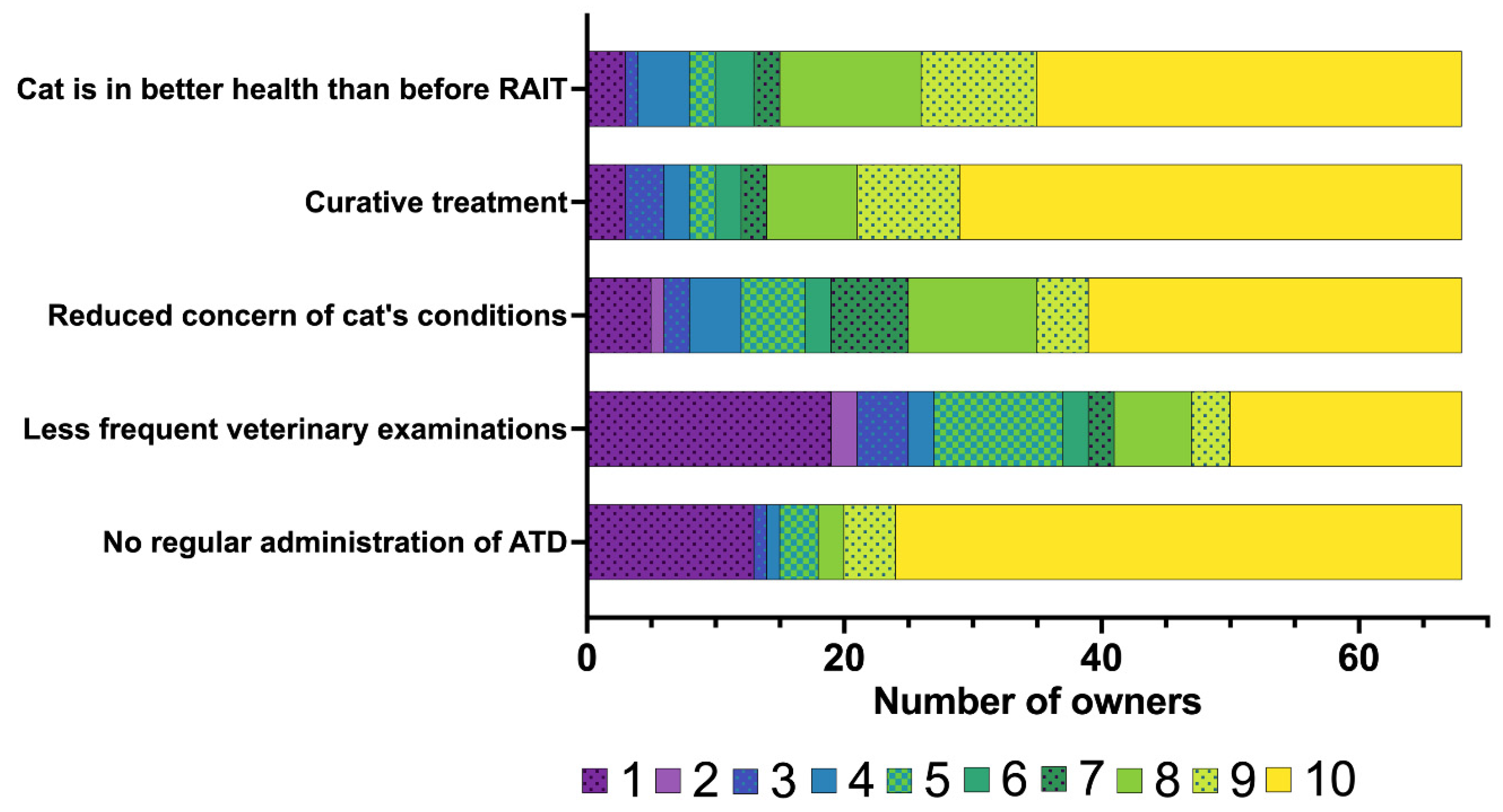

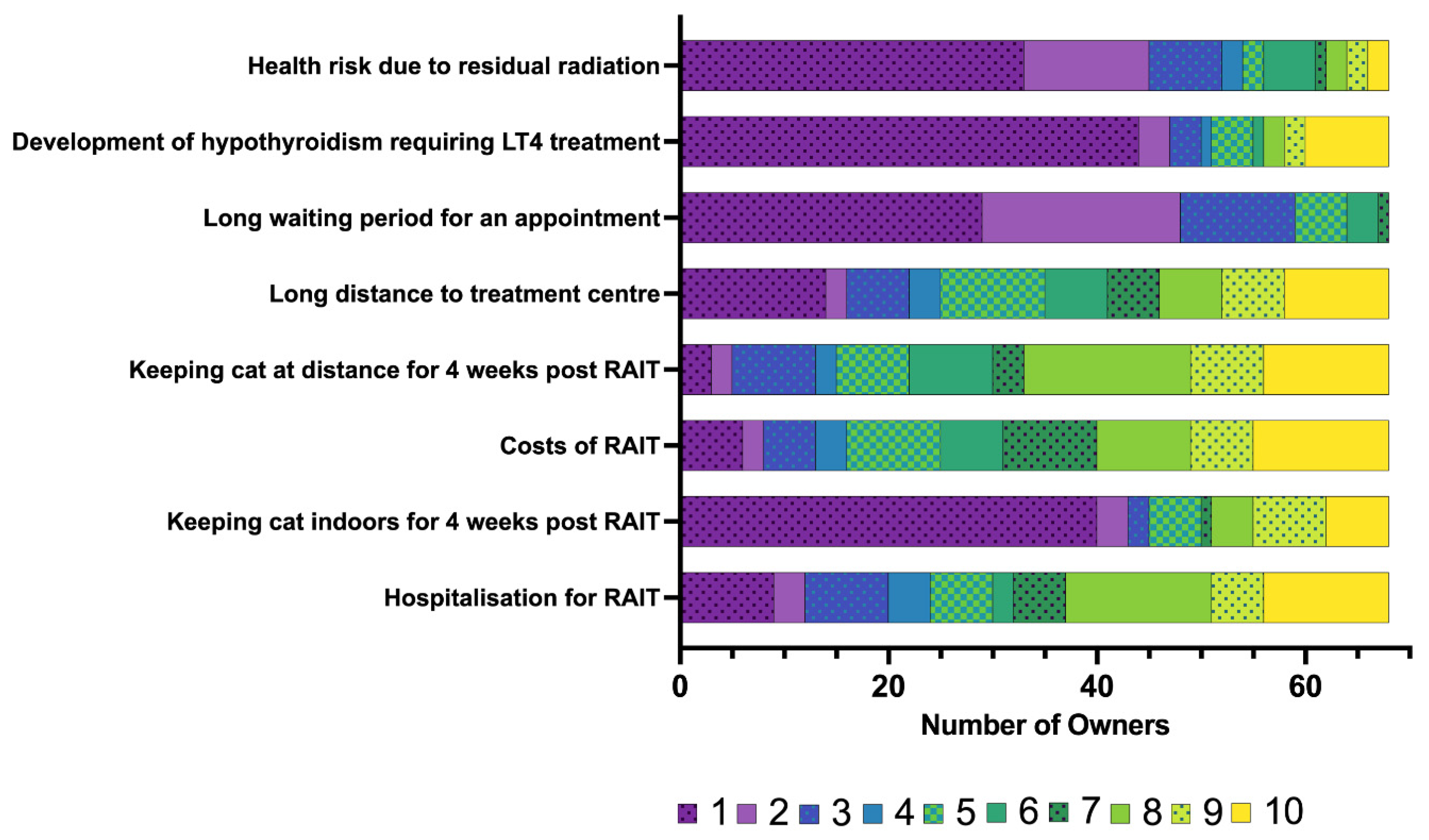

3.4. Concerns About RAIT and Hospitalisation Expressed by the Owners Prior to RAIT

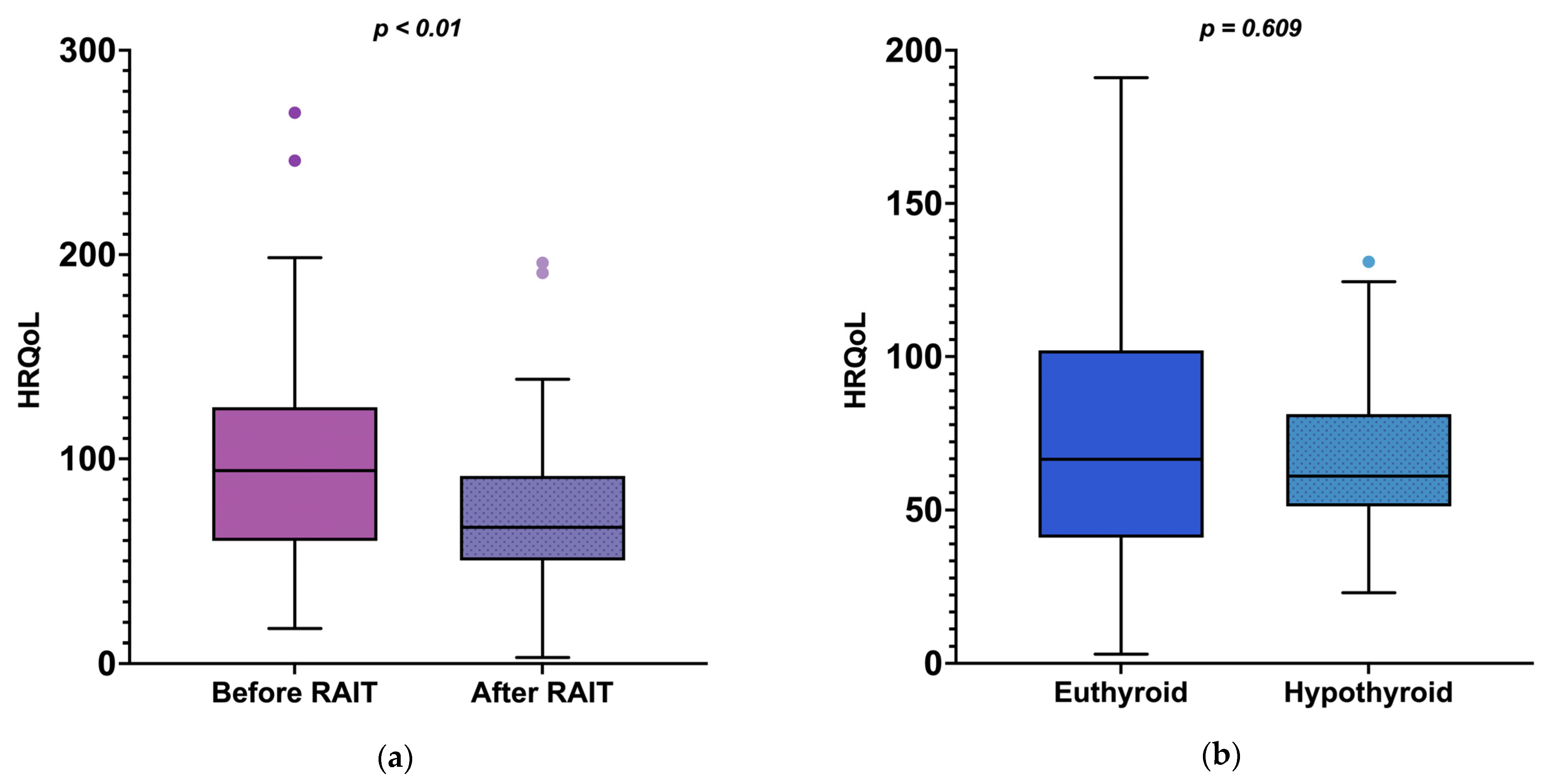

3.5. Outcome of the RAIT and Comparison of Clinical Signs and QoL Before and Six Months After RAIT

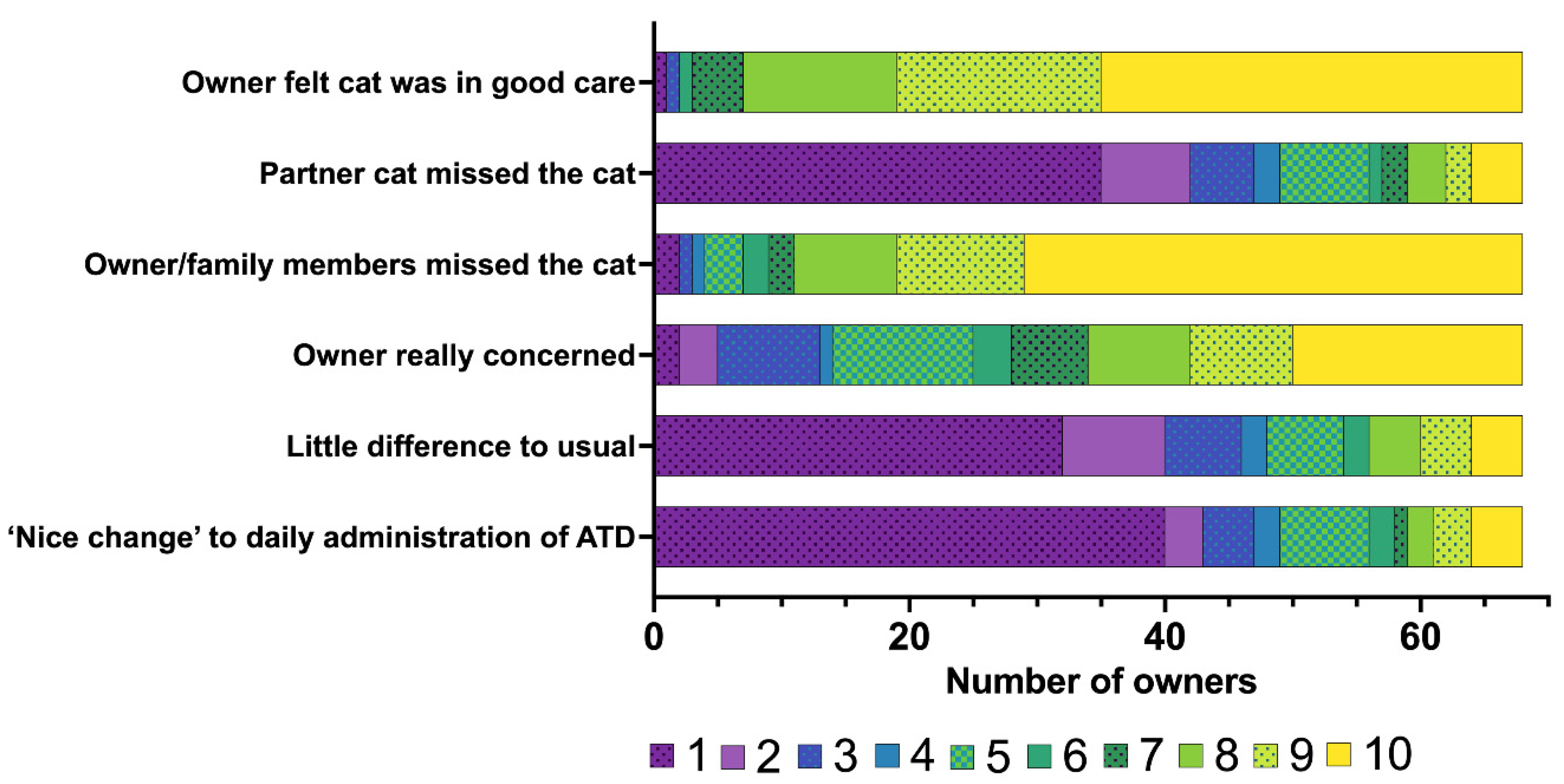

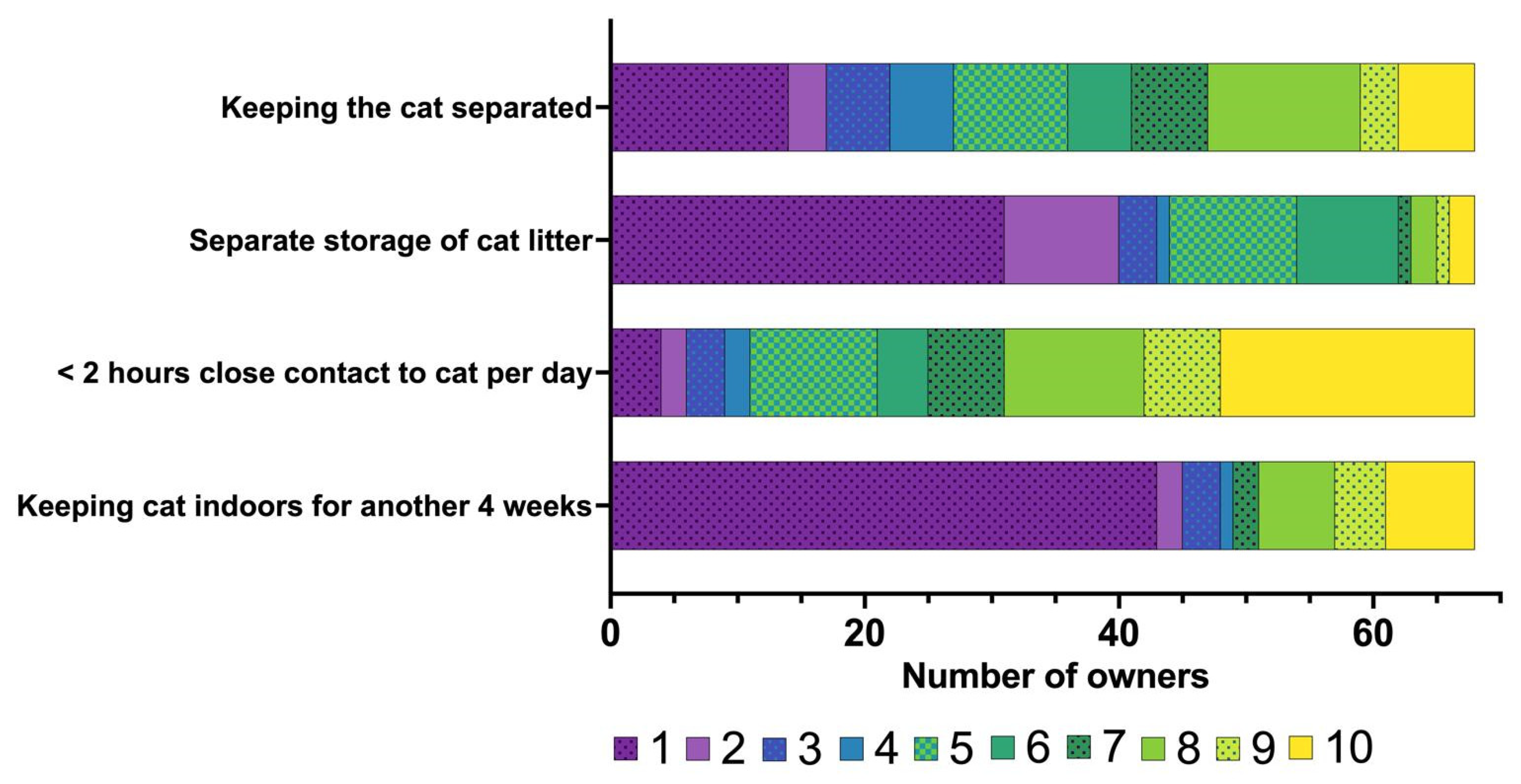

3.6. Owners’ Perception of the Hospitalisation and the Immediate Period Following Discharge from the Hospital, Including Radiation Safety Measures

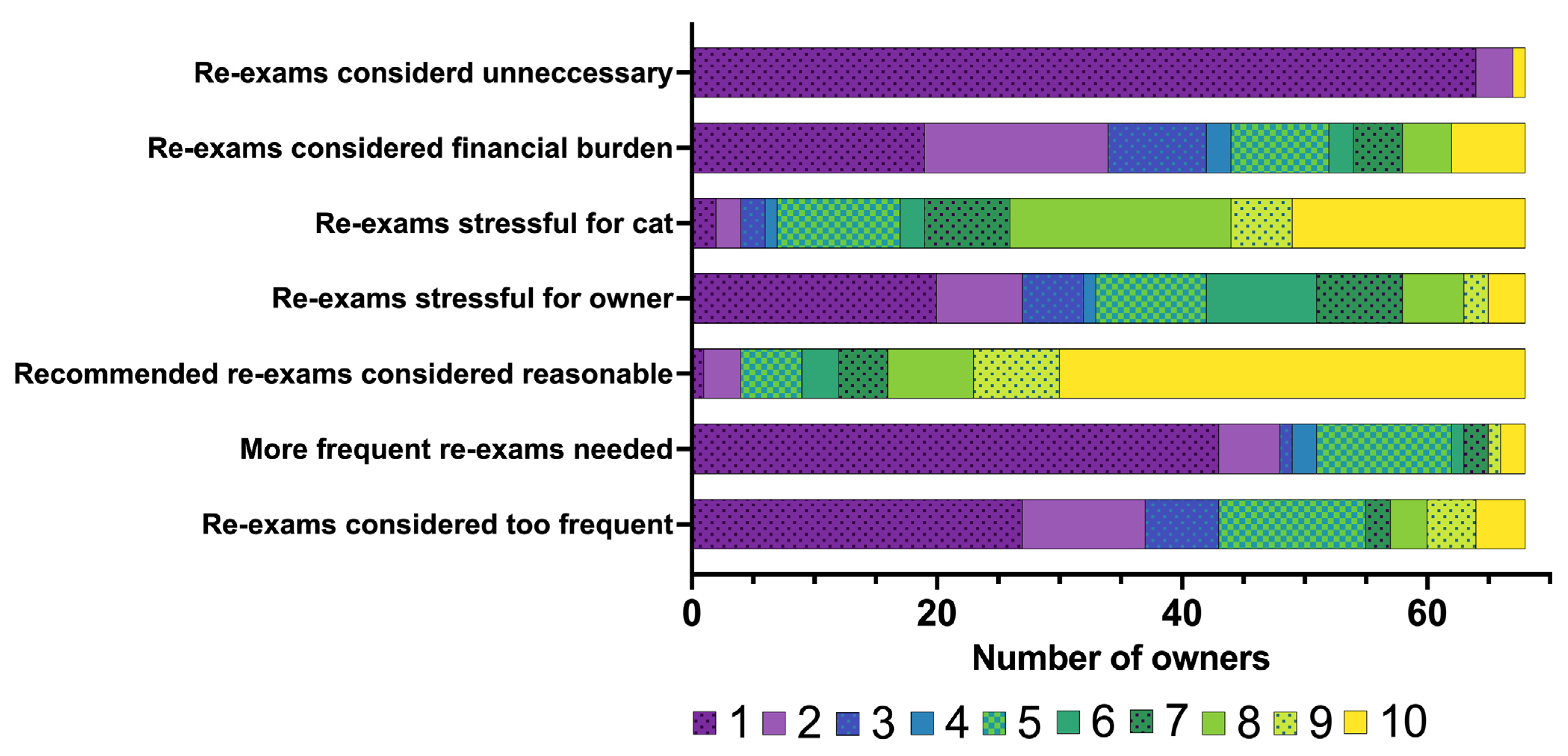

3.7. Re-Examinations Following RAIT and Support Given by Attending Clinicians During Follow-Up

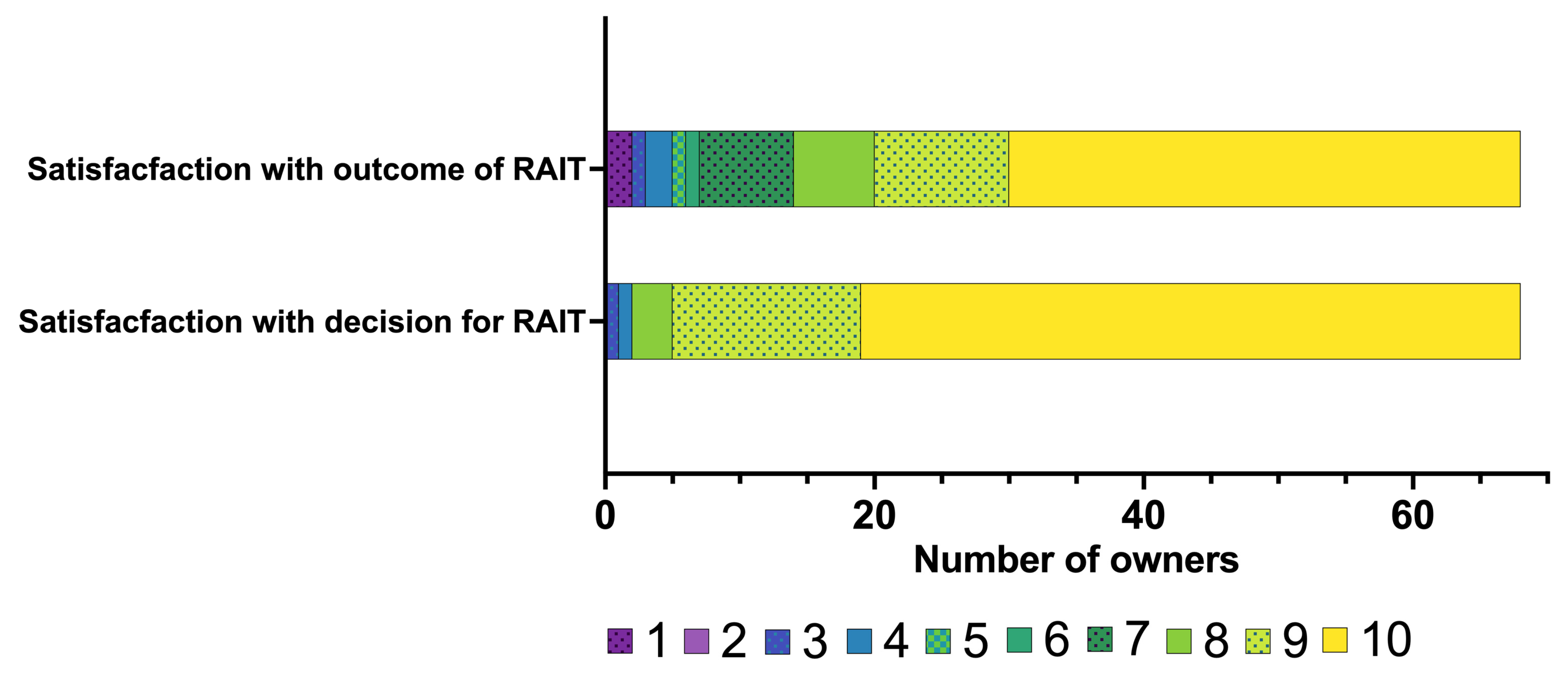

3.8. Overall Satisfaction with RAIT

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ATDs | Antithyroid drugs |

| HRQoL | Health-related quality of life |

| IQR | Interquartile range |

| LID | Low iodine diet |

| LT4 | Levothyroxine |

| QoL | Quality of life |

| RAI | Radioiodine |

| RAIT | Radioiodine treatment |

| RI | Reference interval |

| TSH | Thyroid stimulating hormone |

| TT4 | Total thyroxine |

References

- McLean, J.L.; Lobetti, R.G.; Schoeman, J.P. Worldwide Prevalence and Risk Factors for Feline Hyperthyroidism: A Review. J. S. Afr. Vet. Assoc. 2014, 85, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peterson, M.E. Radioiodine Treatment of Hyperthyroidism. Clin. Tech. Small Anim. Pract. 2006, 21, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peterson, M.E. Hyperthyroidism in Cats: Considering the Impact of Treatment Modality on Quality of Life for Cats and Their Owners. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Am. Small Anim. Pract. 2020, 50, 1065–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carney, H.C.; Ward, C.R.; Bailey, S.J.; Bruyette, D.; Dennis, S.; Ferguson, D.; Hinc, A.; Rucinsky, A.R. Guidelines for the Management of Feline Hyperthyroidism. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2016, 18, 400–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blunschi, F.; Schofield, I.; Muthmann, S.; Bauer, N.B.; Hazuchova, K. Development and Validation of a Questionnaire to Assess Health-Related Quality-of-Life in Cats with Hyperthyroidism. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2024, 38, 1384–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgs, P.; Murray, J.K.; Hibbert, A. Medical Management and Monitoring of the Hyperthyroid Cat: A Survey of UK General Practitioners. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2014, 16, 788–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopecny, L.; Higgs, P.; Hibbert, A.; Malik, R.; Harvey, A.M. Management and Monitoring of Hyperthyroid Cats: A Survey of Australian Veterinarians. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2016, 19, 559–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boland, L.A.; Murray, J.K.; Bovens, C.P.; Hibbert, A. A Survey of Owners’ Perceptions and Experiences of Radioiodine Treatment of Feline Hyperthyroidism in the UK. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2014, 16, 663–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caney, S.M.A. An Online Survey to Determine Owner Experiences and Opinions on the Management of Their Hyperthyroid Cats Using Oral Anti-Thyroid Medications. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2013, 15, 494–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Voogt, C.; Williams, L.; Stammeleer, L.; Peremans, K.; Vandermeulen, E.; Paepe, D.; Daminet, S. Radioiodine Treatment in Hyperthyroid Cats: Insights into the Characteristics of Owners and Their Cats, and Owner Motivation and Perceptions. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2023, 25, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doit, H.; Dean, R.S.; Duz, M.; Brennan, M.L. A Systematic Review of the Quality of Life Assessment Tools for Cats in the Published Literature. Vet. J. 2021, 272, 105658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skowronski, J.J.; Walker, W.R.; Henderson, D.X.; Bond, G.D. The Fading Affect Bias: Its History, Its Implications, and Its Future. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2014, 49, 163–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, W.R.; Skowronski, J.J.; Thompson, C.P. Life Is Pleasant—And Memory Helps to Keep It That Way! Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2003, 7, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthmann, S.; Schofield, I.; Kersting, M.; Blunschi, F.; Tiefenbrunner, J.L.; Bauer, N.B.; Hazuchova, K. Influence of Owner Personality and Other Owner-, Cat- and Treatment-Related Factors on the Perception of Quality of Life in Cats with Hyperthyroidism. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2025, 39, e70091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hibbert, A.; Gruffydd-Jones, T.; Barrett, E.L.; Day, M.J.; Harvey, A.M. Feline Thyroid Carcinoma: Diagnosis and Response to High-Dose Radioactive Iodine Treatment. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2009, 11, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menzel, P.A.; Lin, J.; Güssow, A.; Patzelt, V.; Bauer, N.; Hazuchova, K. A Effect of Presence of Uni-or Bilateral Thyroid Adenoma on Recovery of Pituitary-Thyroid Axis and Creatinine Concentration in Radioiodine-Treated Cats. Animals 2024, 14, 2627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, M.E.; Carmody, S.; Rishniw, M. Hyperthyroid Cats That Develop Azotemia Following Successful Radioiodine Treatment Have Shorter Survival Times Compared to Cats That Remain Nonazotemic. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2024, 263, 454–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puig, J.; Cattin, I.; Seth, M. Concurrent Diseases in Hyperthyroid Cats Undergoing Assessment Prior to Radioiodine Treatment. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2015, 17, 537–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daminet, S.; Kooistra, H.S.; Fracassi, F.; Graham, P.A.; Hibbert, A.; Lloret, A.; Mooney, C.T.; Neiger, R.; Rosenberg, D.; Syme, H.M.; et al. Best Practice for the Pharmacological Management of Hyperthyroid Cats with Antithyroid Drugs. J. Small Anim. Pract. 2014, 55, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, M.E.; Broome, M.R.; Rishniw, M. Prevalence and Degree of Thyroid Pathology in Hyperthyroid Cats Increases with Disease Duration: A Cross-Sectional Analysis of 2096 Cats Referred for Radioiodine Therapy. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2016, 18, 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, N.; Murray, J.K.; Fonfara, S.; Hibbert, A. Clinicopathological Features and Comorbidities of Cats with Mild, Moderate or Severe Hyperthyroidism: A Radioiodine Referral Population. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2018, 20, 1130–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNicholas, J.; Gilbey, A.; Rennie, A.; Ahmedzai, S.; Dono, J.-A.; Ormerod, E. Education and Debate Pet Ownership and Human Health: A Brief Review of Evidence and Issues. BMJ 2005, 331, 1252–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finka Id, L.R.; Ward, J.; Farnworth, M.J.; Mills, D.S. Owner Personality and the Wellbeing of Their Cats Share Parallels with the Parent-Child Relationship. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0211862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voith, V.L. Attachment of People to Companion Animals. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Small Anim. Pract. 1985, 15, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlstead, K.; Brown, J.L.; Strawn, W. Behavioral and Physiological Correlates of Stress in Laboratory Cats. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1993, 38, 143–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, S.L.H. Environmental Enrichment. Practical Strategies for Improving Feline Welfare. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2009, 11, 901–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeiler, G.E.; Fosgate, G.T.; van Vollenhoven, E.; Rioja, E. Assessment of Behavioural Changes in Domestic Cats During Short-Term Hospitalisation. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2014, 16, 499–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eschle, S.; Hartmann, K.; Bergmann, M. Compliance of Dog and Cat Owners in Preventive Health Care. Tierarztl. Prax. 2020, 48, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berendsen, M.; Knol, B. Treatment Compliance. Tijdschr Diergeneeskd 2002, 127, 548–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, M.E.; Carothers, M.A.; Gamble, D.A.; Rishniw, M. Spontaneous Primary Hypothyroidism in 7 Adult Cats. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2018, 32, 1864–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthmann, S.; Schofield, I.; Kersting, M.; Blunschi, F.; Bauer, N.; Hazuchova, K. Influence of the Owner’s Personality and Other Owner-, Cat- and Treatment-Related Facets on the Perception of the Quality of Life for Cats with Hyperthyroidism [Abstract]. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2024, 38, 3537–3694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M.; Choi, S.; Kim, S.; Ko, A.; Son, J.S.; Park, S.M. Association of Thyroid Status with Health-Related Quality of Life in Korean Older Adults. Korean J. Fam. Med. 2020, 41, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.J.; Lee, E.J.; Lee, Y.J.; Choi, S.H.; Park, J.H.; Lee, S.B.; Lim, S.; Lee, W.W.; Jang, H.C.; Cho, B.Y.; et al. Subclinical Hypothyroidism (SCH) Is Not Associated with Metabolic Derangement, Cognitive Impairment, Depression or Poor Quality of Life (QoL) in Elderly Subjects. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2010, 50, e68–e73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, T.L.; Philhower, C.L. Socioemotional Correlates of Self-Reported Menstrual Cycle Irregularity in Premenopausal Women. Psychosom. Med. 2003, 65, 1065–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCambridge, J.; Witton, J.; Elbourne, D.R. Systematic Review of the Hawthorne Effect: New Concepts Are Needed to Study Research Participation Effects. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2014, 67, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, B.C.; Pak, A.W. A Catalog of Biases in Questionnaires. Prev. Chronic Dis. Public Health Res. Pract. Policy 2005, 2, A13. [Google Scholar]

- Reja, U.; Manfreda, K.L.; Hlebec, V.; Vehovar, V. Open-Ended vs. Close-Ended Questions in Web Questionnaires. Dev. Appl. Stat. 2003, 19, 159–177. [Google Scholar]

| Parameter | Choice of Options | Number n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 3 to 6 years | 2 (3) |

| 7 to 10 years | 14 (18) | |

| 11 to 14 years | 50 (64) | |

| Over 15 years | 11 (14) | |

| Unknown | 1 (1) | |

| Sex | Male | 0 (0) |

| Male, neutered | 41 (53) | |

| Female | 1 (1) | |

| Female, neutered | 36 (46) | |

| Breed | European Shorthair | 55 (71) |

| Mixed Breed | 7 (9) | |

| Norwegian Forest | 4 (5) | |

| Maine Coon | 2 (3) | |

| British Shorthair | 2 (3) | |

| Persian | 1 (1) | |

| Ragdoll | 1 (1) | |

| Others | 6 (8) |

| Parameter | Choice of Options | Number n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Duration of hyperthyroidism | 6 months or less | 33 (42) |

| 7 to 12 months | 19 (25) | |

| 1 to 2 years | 16 (21) | |

| 3 years or longer | 6 (8) | |

| Unknown | 4 (5) | |

| Treatment before RAIT | Antithyroid drugs | 57 (73) |

| Iodine-reduced diet | 4 (5) | |

| RAIT | 2 (3) | |

| No treatment | 15 (19) | |

| Thyroid status prior to RAIT | Hyperthyroid | 34 (44) |

| Euthyroid | 34 (44) | |

| Hypothyroid | 2 (3) | |

| Unknown | 8 (10) | |

| Frequency of thyroid hormone evaluation | Four times a year | 23 (29) |

| Three times a year | 15 (19) | |

| Twice a year | 4 (5) | |

| Once a year | 8 (10) | |

| Other | 28 (36) | |

| Comorbidities | No other disease | 37 (47) |

| Dental disease | 27 (34) | |

| Musculoskeletal disease | 9 (11) | |

| Heart disease | 7 (8) | |

| Respiratory tract disease | 5 (6) | |

| Chronic kidney disease | 2 (3) | |

| Gastrointestinal disease | 2 (3) | |

| Skin disease | 2 (3) | |

| Urinary tract disease | 1 (1) | |

| Other | 15 (18) | |

| Treatment for comorbidities | No treatment | 57 (73) |

| Oral medication | 14 (17) | |

| Special diet | 3 (4) | |

| Medical treatment with regular injections | 2 (3) | |

| Other | 2 (3) |

| Parameter | Choice of Options | Number n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Main reason for choosing RAIT | Because RAIT is the treatment of choice (“gold standard”). | 27 (35) |

| The cat has side effects from the antithyroid drugs. | 18 (23) | |

| The owner wanted RAIT since the cat was diagnosed. | 11 (14) | |

| The cat does not respond to antithyroid drugs. | 7 (9) | |

| Advice from primary veterinarian. | 5 (6) | |

| Difficulties administering antithyroid medication. | 3 (4) | |

| Other reasons. | 7 (9) | |

| How the owners learned about the possibility of RAIT at the referral clinic | Advice from primary care veterinarian. | 50 (64) |

| Internet. | 33 (42) | |

| Social media. | 8 (10) | |

| Owner already owned a cat treated with RAIT. | 1 (1) | |

| Travel distance to the referral clinic | Less than 100 km. | 16 (21) |

| 100 to 200 km. | 27 (35) | |

| 200 to 300 km. | 18 (23) | |

| 300 to 400 km. | 8 (10) | |

| More than 400 km. | 9 (12) | |

| Waiting period for the appointment | Less than 1 month. | 23 (29) |

| 1 to 2 months. | 44 (56) | |

| 3 to 4 months. | 26 (33) | |

| 5 to 6 months. | 6 (8) |

| Prior to RAIT | Six Months After RAIT | p-Values | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | IQR | Median | IQR | ||

| Weight loss | 5 | 3–8 | 1 | 1–1 | <0.01 |

| Muscle wasting | 3 | 1–6 | 1 | 1–2 | <0.01 |

| Restlessness | 5 | 2–2.8 | 2 | 1–3 | <0.01 |

| Aggression | 1 | 1–3.8 | 1 | 1–2 | <0.01 |

| Vomiting | 3 | 1–5.8 | 1 | 1–3 | <0.01 |

| Diarrhoea | 2 | 1–3 | 1 | 1–2 | 0.04 |

| Polyuria | 4 | 1–6 | 1.5 | 1–3 | <0.01 |

| Polydipsia | 4 | 2–7 | 2 | 1–3.3 | <0.01 |

| Poor coat quality | 3 | 2–7 | 1 | 1–2 | <0.01 |

| HRQoL-Score | 92.3 | 67.3–123.5 | 66.5 | 50.8–89.9 | <0.01 |

| General concern about the cat’s hyperthyroidism | 9 | 7–10 | 2 | 1–4 | <0.01 |

| Parameter | Choice of Options | Number n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Comorbidities | No other disease | 35 (51) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 10 (15) | |

| Heart disease | 2 (3) | |

| Musculoskeletal disease | 1 (1) | |

| Skin disease | 1 (1) | |

| Other | 10 (15) | |

| Treatment for comorbidities | No treatment | 40 (59) |

| Oral medication | 12 (18) | |

| Special diet | 5 (7) | |

| Medical treatment with regular injections | 1 (1) | |

| Other | 10 (15) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Muthmann, S.; Tiefenbrunner, J.L.; Blunschi, F.; Klemm, I.; Bauer, N.B.; Hazuchova, K. Owners’ Experience and Satisfaction with Radioiodine Treatment in Hyperthyroid Cats—A Prospective Questionnaire Study. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 458. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci12050458

Muthmann S, Tiefenbrunner JL, Blunschi F, Klemm I, Bauer NB, Hazuchova K. Owners’ Experience and Satisfaction with Radioiodine Treatment in Hyperthyroid Cats—A Prospective Questionnaire Study. Veterinary Sciences. 2025; 12(5):458. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci12050458

Chicago/Turabian StyleMuthmann, Sofie, Joana Léonie Tiefenbrunner, Fabienne Blunschi, Isabell Klemm, Natali Bettina Bauer, and Katarina Hazuchova. 2025. "Owners’ Experience and Satisfaction with Radioiodine Treatment in Hyperthyroid Cats—A Prospective Questionnaire Study" Veterinary Sciences 12, no. 5: 458. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci12050458

APA StyleMuthmann, S., Tiefenbrunner, J. L., Blunschi, F., Klemm, I., Bauer, N. B., & Hazuchova, K. (2025). Owners’ Experience and Satisfaction with Radioiodine Treatment in Hyperthyroid Cats—A Prospective Questionnaire Study. Veterinary Sciences, 12(5), 458. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci12050458