Evaluation of Antimicrobial Usage Supply Chain and Monitoring in the Livestock and Poultry Sector of Pakistan

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Methodological Approach

2.2. Selection Criteria for Stakeholders:

- (a)

- Institutional Representation: Stakeholders or key institutions engaged in import, regulation, distribution, and use of antimicrobials, such as regulatory bodies, the human health sector, veterinary departments, Customs, veterinary educational establishments, fisheries and aquaculture, drug quality testing laboratories, and research institutes.

- (b)

- Expertise and Knowledge: Participants with expertise in veterinary medicine, animal husbandry, pharmaceuticals, public health, and regulatory affairs related to antimicrobials.

- (c)

- Geographical Representation: Participation from all regions or provinces within the country to capture regional variations in AMU practices and regulations.

2.3. Stakeholder Enagaged

- (a)

- International Organizations: International organizations invited to the workshop included the World Organisation for Animal Health, World Health Organization, Pakistan (WHO), Food and Agriculture Organization, Pakistan (FAO), and the Fleming Fund Country Grant, Pakistan.

- (b)

- National Institutions Working with Import of Antimicrobials: These included the Ministry of National Food Security and Research, Drug Regulatory Authority of Pakistan (DRAP), Customs Department, Pakistan, and poultry, dairy and pharmaceutical associations.

- (c)

- National Institutions Working with Regulation of Antimicrobials: In addition to the DRAP, it included National Veterinary Laboratories, Islamabad.

- (d)

- National Institutions Working with Use of Antimicrobials: These included the Fisheries Development Board, Livestock and Dairy Development Board, and Directorate of Livestock, Islamabad, on the federal level. Livestock and Dairy Development Departments (L&DD) from Punjab, Khyber Pakhtunkhaw, Sindh, Balochistan, Azad Jammu and Kashmir, and Gilgit Baltistan represented the provincial and regional governments. University of Agriculture, Faisalabad, and Islamia University, Bahalwapur, represented the veterinary academic institutions. The Poultry, Dairy, and Veterinary Pharmaceutical Associations participated as private sector representatives.

2.4. Development of Activity Sheets and Data Collection

2.5. Stakeholder Consultation/Analysis

- (a)

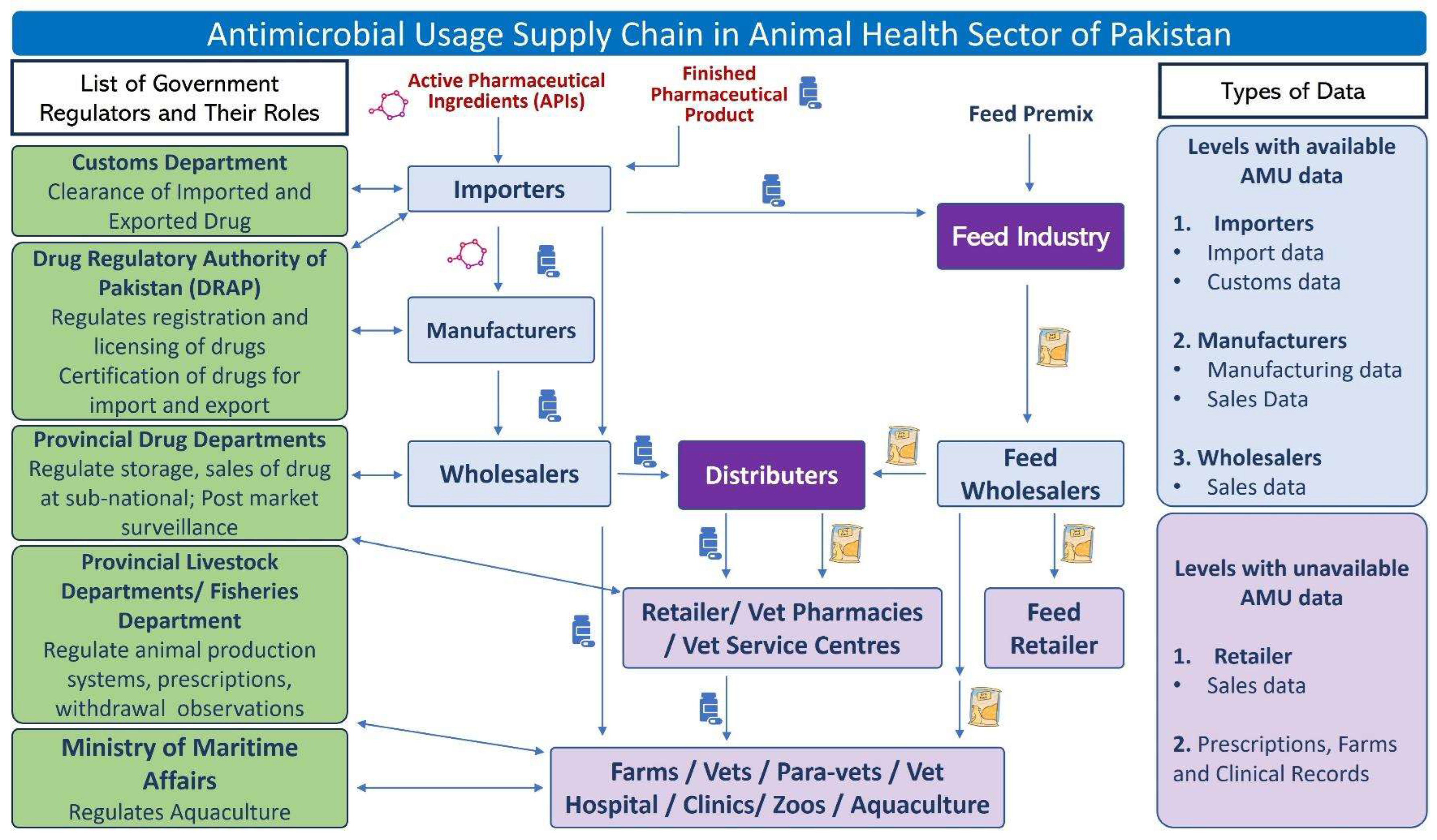

- Mapping of AMU Supply Chain: During the first day of the workshop, regulatory authorities and other participants were divided into groups to map the sources of the supply chain of antimicrobial agents intended for use in animals. However, before seeking this important information, the objectives of the activity were discussed. To sensitize the participants and emphasize the significance of national data reporting and regulatory procedures at federal and provincial levels, detailed presentations were delivered. These covered topics such as the global AMU database and the importance of national data reporting (presented by WOAH), the regulatory process around antimicrobial import, registration, sale, and usage (presented by the Drug Regulatory Authority of Pakistan), the regulatory frameworks for monitoring antimicrobial usage (presented by the Livestock and Dairy Development Department Punjab), and the import process and real-time surveillance capabilities for antimicrobials (presented by the Customs Department). This preparation aimed to ensure effective group discussions focused on mapping the AMU supply chain.

- (b)

- AMU Monitoring: On second day of the workshop, following the technical presentations on status and activities on AMR and AMU by various stakeholders, the participants were divided into three groups based on their expertise to brainstorm on (i) current legislation and governance status for monitoring of AMU in Pakistan to identify the key government regulators and their roles in regulating AMU along the supply chain; (ii) national AMU data collection and monitoring system to identify types of AMU data that each stakeholder can provide to the MoNFS&R, and (iii) monitoring of AMU at end-user level to identify priority activities to enhance national AMU-monitoring system in Pakistan. The aim of this exercise was to consider the various steps and conditions for marketing and using various antimicrobial products among livestock species in Pakistan. Prior to the workshop, the organizers drafted a map of antimicrobial chain supplies and shared it with the breakout groups to confirm and modify the pathways for AMU in livestock species.

3. Results

3.1. The AMU Supply Chain of Pakistan

3.2. Legislation and Governance Status for Monitoring of AMU in Pakistan

3.3. National AMU Data Collection and Monitoring System

3.4. Monitoring of AMU at End-User Level

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Khan, M.S.; Durrance-Bagale, A.; Legido-Quigley, H.; Mateus, A.; Hasan, R.; Spencer, J.; Hanefeld, J. ’LMICs as Reservoirs of AMR’: A Comparative Analysis of Policy Discourse on Antimicrobial Resistance with Reference to Pakistan. Health Policy Plan 2019, 34, 178–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Founou, R.C.; Blocker, A.J.; Noubom, M.; Tsayem, C.; Choukem, S.P.; Dongen, M.V.; Founou, L.L. The COVID-19 pandemic: A threat to antimicrobial resistance containment. Future Sci. OA 2021, 7, FSO736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennani, H.; Mateus, A.; Mays, N.; Eastmure, E.; Stärk, K.D.C.; Häsler, B. Overview of Evidence of Antimicrobial Use and Antimicrobial Resistance in the Food Chain. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Government of Pakistan. Economic Survey of Pakistan; Finance Division, Economic Advisor’s Wing: Islamabad, Pakistan, 2023.

- Saman, A.; Chaudhry, M.; Ijaz, M.; Shaukat, W.; Zaheer, M.U.; Mateus, A.; Rehman, A. Assessment of Knowledge, Perception, Practices and Drivers of Antimicrobial Resistance and Antimicrobial Usage Among Veterinarians in Pakistan. Prev. Vet. Med. 2023, 212, 105836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Animal Husbandry Commissioner. National Surveillance Strategy for Antimicrobial Resistance in Healthy Food Animals; Animal Husbandry Commissioner, Livestock Wing, Ministry of National Food Security and Research, Government of Pakistan: Islamabad, Pakistan, 2021.

- Qiu, Y.; Ferreira, J.P.; Ullah, R.W.; Flanagan, P.; Zaheer, M.U.; Tahir, M.F.; Alam, J.; Hoet, A.E.; Song, J.; Akram, M. Assessment of the Implementation of Pakistan’s National Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance in the Agriculture and Food Sectors. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH). The OIE Strategy on Antimicrobial Resistance and the Prudent Use of Antimicrobials; OIE: Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Matthiessen, L.E.; Hald, T.; Vigre, H. System Mapping of Antimicrobial Resistance to Combat a Rising Global Health Crisis. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 816943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Government of the Punjab. The Punjab Gazette; Law and Parliamentary Affairs Department: Lahore, Pakistan, 2017. Available online: https://poultry.punjab.gov.pk/system/files/PPPRULE2017.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2021).

- Malik, F.; Figueras, A. Analysis of the Antimicrobial Market in Pakistan: Is It Really Necessary Such a Vast Offering of “Watch” Antimicrobials? Antibiotics 2019, 8, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Annual International Trade Statistics by Country (HS02). Trend Economy. 2021. Available online: https://trendeconomy.com/data/h2/Pakistan/2941 (accessed on 15 July 2021).

- Kotwani, A.; Joshi, J.; Why We Need Smart Regulation to Contain Antimicrobial Resistance. Down to Earth. 2020. Available online: https://www.downtoearth.org.in/blog/health/why-we-need-smart-regulation-to-contain-antimicrobial-resistance-74311 (accessed on 15 August 2021).

- Poupaud, M.; Putthana, V.; Patriarchi, A.; Caro, D.; Agunos, A.; Tansakul, N.; Goutard, F.L. Understanding the veterinary antibiotics supply chain to address antimicrobial resistance in Lao PDR: Roles and interactions of involved stakeholders. Acta Trop. 2021, 220, 105943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Organization for Animal Health (WOAH). WOAH Annual Report on Antimicrobial Agents Intended for Use in Animals. 2nd Report. 2017. Available online: https://www.oie.int/fileadmin/Home/eng/Our_scientific_expertise/docs/pdf/AMR/Annual_Report_AMR_2.pdf (accessed on 15 August 2021).

- DANMAP. Use of Antimicrobial Agents and Occurrence of Antimicrobial Resistance in Bacteria from Food Animals, Food and Humans in Denmark; Danish Integrated Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring and Research Programme: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2017. Available online: http://www.danmap.org/~/media/Projekt%20sites/Danmap/DANMAP%20reports/DANMAP%202013/DANMAP%202013.ashx (accessed on 15 July 2021).

- European Medicines Agency. Trends in the Sales of Veterinary Antimicrobial Agents in Nine European Countries (2005–2009) (EMA/238630/2011). 2011. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/report/trends-sales-veterinary-antimicrobial-agents-nine-european-countries_en.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2021).

- Viola, C.; DeVincent, S.J. Overview of Issues Pertaining to the Manufacture, Distribution, and Use of Antimicrobials in Animals and Other Information Relevant to Animal Antimicrobial Use Data Collection in the United States. Prev. Vet. Med. 2016, 73, 111–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schar, D.; Sommanustweechai, A.; Laxminarayan, R.; Tangcharoensathien, V. Surveillance of antimicrobial consumption in animal production sectors of low-and middle-income countries: Optimizing use and addressing antimicrobial resistance. PLoS Med. 2018, 15, e1002521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umair, M.; Tahir, M.F.; Ullah, R.W.; Ali, J.; Siddique, N.; Rasheed, A.; Akram, M.; Zaheer, M.U.; Mohsin, M. Quantification and Trends of Antimicrobial Use in Commercial Broiler Chicken Production in Pakistan. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Topic | Current Gaps/Challenges | Way Forward | Lead Implementer | Collaborator | Timeline |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| National Data Collection System | No system in place. | AMU data collection system to be developed | AHC MoNFS&R FDC, MoMA | DRAP, Customs, Prov LDD, Prov Drug Regulatory Authorities (DRAs) | |

| Type of AMU Data | No specific demarcation on Critical AMs/GPs, etc. | Differentiation of AMs according to intl. standards | AHC, FDC | DRAP, Customs, Prov LDD, Prov DRA | Short term |

| Main Importers of AMs | Most importers are private pharmaceutical companies and importers/distributors. | List of importers needs to be identified and recorded. | AHC and FDC | DRAP, Customs | Short term |

| List of AMs Harmonized as per WOAH and WHO List | No list of AMs identified and notified as per critical AMs notified by WOAH and WHO, neither are any legislation/guidelines available for monitoring and data collection | List of critical AMs to be notified. Guidelines to be formulated and legislation is required for monitoring AMs used. | AHC and FDC | DRAP, Customs, Prov L&DD, Prov DRA | Short term |

| Type of Data to be Provided to MoNFS&R and MoMA | No systematic mechanism is available; no legislation is available. | System to be developed for data collection and sharing with MoNFS&R and MoMA through AHC and FDC from the private sector as well as federal and provincial regulators | AHC, FDC | DRAP, Customs, Prov LDD, Prov DRA, Pharmaceuticals | Long term |

| Gaps and Barriers for AMU Data Collection | No guidelines, legislation, No SOPs, No system exists | Develop system, guidelines, SOPs, legislative reforms | AHC/FDC | DRAP, Customs, Prov L&DD, Prov DRA | Medium term |

| Way Forward | Political commitment, HR issues, legislative issues, need to develop a harmonized system for data collection, effective communication between federal and provinces, advocacy, and awareness of AMU. | Form a taskforce or technical working group (TWG) on AMU |

| Topic | Current Gaps/Challenges | Way Forward | Lead Implementer | Collaborator | Timeline |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMU Monitoring | No system in place | Surveillance plan/legislation | Federal and Provinces | Public and Private | Medium term |

| Guidelines/SOPs | Don’t exist | Develop guidelines/SOPs | Federal and Provinces | Academia, Livestock Dept, Res. Institute, Association, Fish Dept | Medium term |

| Development of a monitoring system | No data base | Pilot study in different production systems | Federal and Provinces | Livestock Dept, Association Farmers | Short term |

| Publications | Only one that is too limited to the human health component [11] | More planned studies | Academia, Res. Institute | Livestock Dept, Association Farmers | Long term |

| Implementations and Challenges | Lack of awareness, trained manpower, funding, political interest | Allocation of budget, political will, training | Federal and Provinces | Planning and Finance | Long term |

| Roles and responsibilities | Federal legislation | Legislation, implementation, data analysis, reporting | |||

| Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices surveys | No planned activity | Planned study, multi-sectorial approach, awareness, AMR day | livestock dept | Academia, Research Institutes, NGO’s, Associations, Farmers |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tahir, M.F.; Wasee Ullah, R.; Wang, J.; Dukpa, K.; Zaheer, M.U.; Bahadur, S.U.K.; Talib, U.; Alam, J.; Akram, M.; Salman, M.; et al. Evaluation of Antimicrobial Usage Supply Chain and Monitoring in the Livestock and Poultry Sector of Pakistan. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 215. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci12030215

Tahir MF, Wasee Ullah R, Wang J, Dukpa K, Zaheer MU, Bahadur SUK, Talib U, Alam J, Akram M, Salman M, et al. Evaluation of Antimicrobial Usage Supply Chain and Monitoring in the Livestock and Poultry Sector of Pakistan. Veterinary Sciences. 2025; 12(3):215. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci12030215

Chicago/Turabian StyleTahir, Muhammad Farooq, Riasat Wasee Ullah, Jing Wang, Kinzang Dukpa, Muhammad Usman Zaheer, Sami Ullah Khan Bahadur, Usman Talib, Javaria Alam, Muhammad Akram, Mo Salman, and et al. 2025. "Evaluation of Antimicrobial Usage Supply Chain and Monitoring in the Livestock and Poultry Sector of Pakistan" Veterinary Sciences 12, no. 3: 215. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci12030215

APA StyleTahir, M. F., Wasee Ullah, R., Wang, J., Dukpa, K., Zaheer, M. U., Bahadur, S. U. K., Talib, U., Alam, J., Akram, M., Salman, M., & Irshad, H. (2025). Evaluation of Antimicrobial Usage Supply Chain and Monitoring in the Livestock and Poultry Sector of Pakistan. Veterinary Sciences, 12(3), 215. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci12030215