Study on the Disinfection Efficacy of Common Commercial Disinfectants in China Against Mastitis-Causing Pathogens and Bedding Materials in Large-Scale Dairy Farms

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Preparation of Bacterial Suspension

2.3. Neutralizer Identification Test

Evaluation Criteria

2.4. Determination of Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) and Minimum Bactericidal Concentration (MBC) of Disinfectants

2.5. Quantitative Bactericidal Test on Bacterial Suspension

2.6. Quantitative Bactericidal Test for Carrier Spray Disinfection

2.7. Disinfection of Cubicle Bedding in Dairy Barns

3. Results

3.1. Results of Neutralizer Identification Test

3.2. Determination Results of MIC and MBC Values of the Five Disinfectants Against Isolated Strains

3.3. Quantitative Bactericidal Test in Suspension

3.3.1. Bactericidal Efficacy of Five Disinfectants Against E. coli

3.3.2. Bactericidal Efficacy of Five Disinfectants Against S. aureus

3.4. Spray Disinfection Efficacy of Five Disinfectants on Stainless Steel Coupons

3.4.1. Spray Disinfection Efficacy of Five Disinfectants Against E. coli on Stainless Steel Coupons

3.4.2. Spray Disinfection Efficacy of Five Disinfectants Against S. aureus on Stainless Steel Coupons

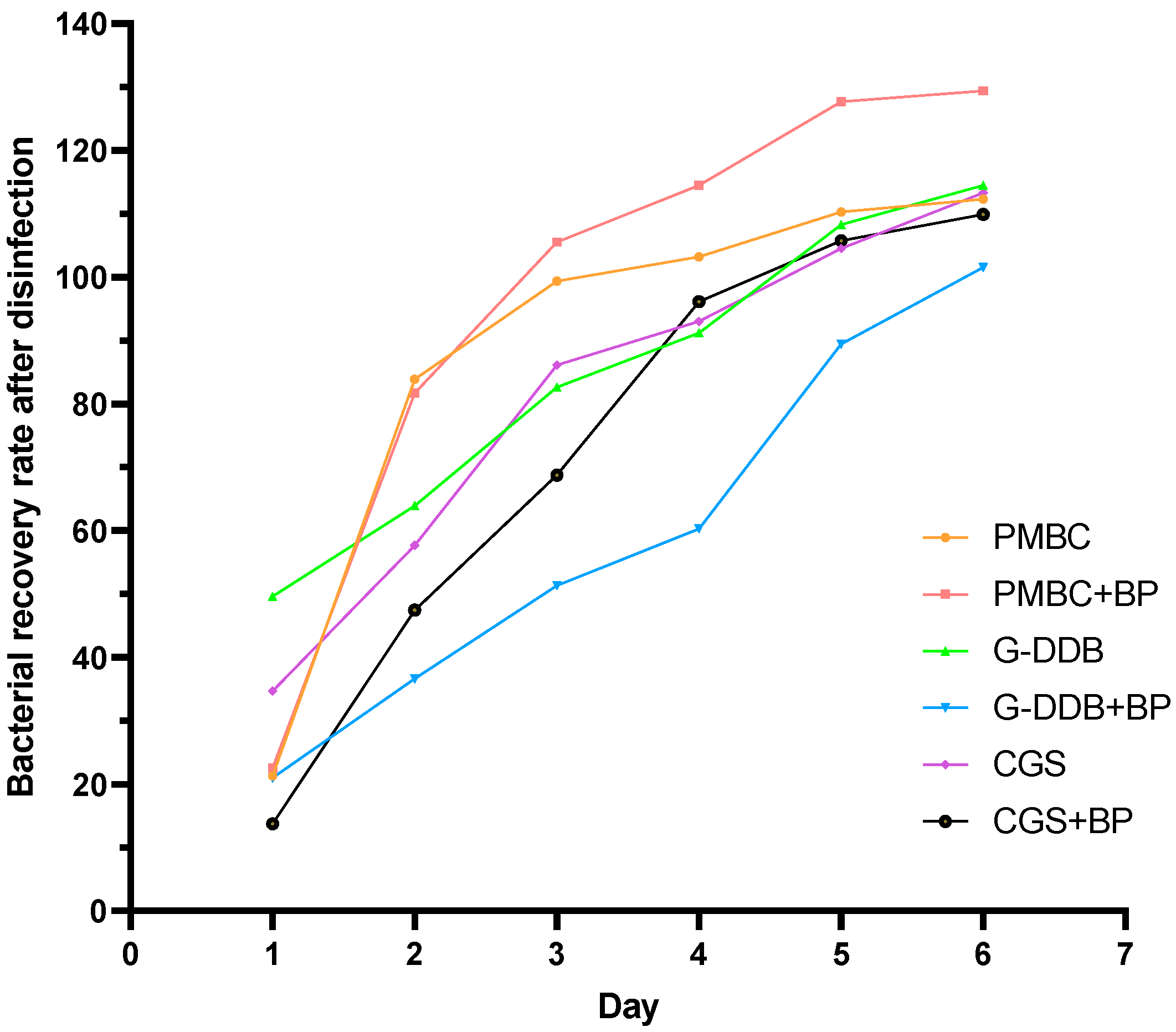

3.5. Disinfection Efficacy and Bacterial Growth–Decline Dynamics of Different Disinfectant Systems on Cow Dung Bedding

Selection Strategy for Cow Dung Bedding Disinfectants

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PVP-I | Polyvinylpyrrolidone–Iodine Solution |

| BKB | Benzalkonium Bromide Preparation |

| CGS | Compound Glutaraldehyde Preparation |

| G–DDB | Glutaraldehyde–Didecyldimethylammonium Bromide Solution |

| PMBC | Potassium Peroxymonosulfate Complex Powder |

| BP | Bleaching Powder |

Appendix A

| Disinfectants | 3 min (%) | 5 min (%) | 10 min (%) | 3 min (%) | 5 min (%) | 10 min (%) | 3 min (%) | 5 min (%) | 10 min (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 °C | 25 °C | 37 °C | 4 °C | 25 °C | 37 °C | 4 °C | 25 °C | 37 °C | |

| PVP-I | |||||||||

| 1:4 | 99.99 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| 1:8 | 99.99 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| 1:16 | 99.55 | 99.68 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| 1:32 | 99.32 | 99.44 | 99.51 | 99.91 | 99.95 | 99.99 | 99.98 | 99.99 | 100.00 |

| BKB | |||||||||

| 1:200 | 97.23 | 96.30 | 99.99 | 99.99 | 99.20 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| 1:400 | 92.50 | 96.20 | 98.18 | 95.23 | 98.30 | 99.99 | 99.99 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| 1:800 | 90.63 | 91.68 | 93.45 | 92.46 | 95.42 | 97.19 | 95.73 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| 1:1600 | 84.62 | 87.25 | 92.18 | 88.21 | 90.26 | 95.80 | 93.25 | 96.20 | 98.30 |

| CGS | |||||||||

| 1:200 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| 1:400 | 99.99 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| 1:800 | 99.69 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 99.99 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| 1:1600 | 99.01 | 96.40 | 98.20 | 99.20 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 99.87 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| G-DDB | |||||||||

| 1:200 | 96.59 | 78.32 | 98.44 | 80.73 | 99.16 | 99.20 | 85.54 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| 1:400 | 86.78 | 74.05 | 85.58 | 75.11 | 91.71 | 95.85 | 81.08 | 98.40 | 99.99 |

| 1:800 | 58.68 | 73.65 | 73.83 | 74.91 | 76.89 | 78.48 | 79.56 | 88.38 | 81.43 |

| 1:1600 | 54.89 | 70.46 | 72.65 | 65.80 | 70.15 | 75.51 | 75.75 | 60.92 | 80.72 |

| PMBC | |||||||||

| 1:200 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| 1:400 | 93.10 | 98.33 | 98.74 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| 1:800 | 91.54 | 95.46 | 97.80 | 99.62 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| 1:1600 | 88.91 | 95.00 | 95.60 | 94.70 | 95.00 | 97.30 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| Disinfectants | 3 min (%) | 5 min (%) | 10 min (%) | 3 min (%) | 5 min (%) | 10 min (%) | 3 min (%) | 5 min (%) | 10 min (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 °C | 25 °C | 37 °C | 4 °C | 25 °C | 37 °C | 4 °C | 25 °C | 37 °C | |

| PVP-I | |||||||||

| 1:4 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| 1:8 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| 1:16 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| 1:32 | 99.84 | 99.98 | 100.00 | 99.99 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| BKB | |||||||||

| 1:200 | 97.93 | 100.00 | 99.99 | 99.99 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| 1:400 | 96.82 | 96.21 | 99.89 | 99.99 | 99.99 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| 1:800 | 91.25 | 92.10 | 94.80 | 93.61 | 96.80 | 97.90 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| 1:1600 | 85.80 | 88.30 | 93.20 | 92.29 | 96.30 | 97.20 | 93.72 | 98.21 | 99.25 |

| CGS | |||||||||

| 1:200 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| 1:400 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| 1:800 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| 1:1600 | 99.99 | 99.99 | 99.99 | 99.99 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| G-DDB | |||||||||

| 1:200 | 97.37 | 78.95 | 99.23 | 81.38 | 99.96 | 100.00 | 86.23 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| 1:400 | 88.01 | 75.10 | 86.80 | 76.72 | 93.68 | 97.91 | 81.90 | 99.39 | 100.00 |

| 1:800 | 59.51 | 74.70 | 74.88 | 76.52 | 78.54 | 80.16 | 80.36 | 89.27 | 81.58 |

| 1:1600 | 55.67 | 71.46 | 73.68 | 67.21 | 71.65 | 77.13 | 76.52 | 61.54 | 77.33 |

| PMBC | |||||||||

| 1:200 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| 1:400 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| 1:800 | 97.75 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| 1:1600 | 93.42 | 95.40 | 97.67 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| Disinfectants | 3 min (%) | 5 min (%) | 10 min (%) | 3 min (%) | 5 min (%) | 10 min (%) | 3 min (%) | 5 min (%) | 10 min (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 °C | 25 °C | 37 °C | 4 °C | 25 °C | 37 °C | 4 °C | 25 °C | 37 °C | |

| PVP-I | |||||||||

| 1:4 | 92.56 | 94.27 | 96.16 | 92.81 | 94.92 | 96.84 | 93.55 | 95.30 | 97.03 |

| 1:8 | 87.28 | 89.26 | 93.77 | 88.13 | 92.19 | 94.21 | 89.92 | 94.83 | 94.80 |

| 1:16 | 84.92 | 86.93 | 90.13 | 86.09 | 91.82 | 91.51 | 87.03 | 92.10 | 92.87 |

| 1:32 | 81.37 | 84.55 | 86.07 | 82.36 | 87.19 | 90.99 | 83.79 | 89.02 | 92.84 |

| BKB | |||||||||

| 1:200 | 80.88 | 83.36 | 85.09 | 84.58 | 86.99 | 88.05 | 92.30 | 96.48 | 97.99 |

| 1:400 | 79.73 | 80.02 | 83.44 | 82.95 | 84.31 | 85.26 | 90.44 | 92.99 | 96.99 |

| 1:800 | 76.08 | 79.82 | 82.41 | 81.27 | 83.33 | 84.38 | 88.83 | 93.67 | 94.92 |

| 1:1600 | 74.28 | 78.67 | 81.54 | 80.64 | 81.63 | 83.50 | 88.45 | 92.81 | 93.79 |

| CGS | |||||||||

| 1:200 | 92.45 | 93.60 | 94.03 | 99.99 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| 1:400 | 90.34 | 92.82 | 93.68 | 99.92 | 99.86 | 99.99 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| 1:800 | 89.98 | 90.30 | 91.68 | 99.85 | 99.79 | 99.89 | 99.99 | 99.99 | 100.00 |

| 1:1600 | 84.06 | 89.69 | 90.98 | 97.62 | 97.72 | 99.85 | 94.78 | 96.29 | 99.88 |

| G-DDB | |||||||||

| 1:200 | 95.73 | 96.77 | 96.97 | 99.99 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| 1:400 | 94.35 | 95.76 | 95.88 | 99.87 | 99.68 | 99.99 | 99.99 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| 1:800 | 93.86 | 93.76 | 95.35 | 99.55 | 99.43 | 99.82 | 99.99 | 99.99 | 100.00 |

| 1:1600 | 85.39 | 91.68 | 93.14 | 96.63 | 97.33 | 98.38 | 93.54 | 95.79 | 99.76 |

| PMBC | |||||||||

| 1:200 | 96.39 | 96.79 | 97.83 | 99.92 | 99.98 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| 1:400 | 92.84 | 96.04 | 97.04 | 99.87 | 99.90 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| 1:800 | 90.10 | 93.65 | 96.34 | 98.76 | 99.81 | 99.95 | 99.99 | 99.99 | 100.00 |

| 1:1600 | 83.90 | 91.37 | 92.55 | 92.28 | 93.47 | 96.91 | 99.99 | 99.99 | 100.00 |

| Disinfectants | 3 min (%) | 5 min (%) | 10 min (%) | 3 min (%) | 5 min (%) | 10 min (%) | 3 min (%) | 5 min (%) | 10 min (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 °C | 25 °C | 37 °C | 4 °C | 25 °C | 37 °C | 4 °C | 25 °C | 37 °C | |

| PVP-I | |||||||||

| 1:4 | 93.04 | 96.16 | 97.09 | 93.25 | 96.88 | 97.20 | 93.88 | 97.20 | 97.32 |

| 1:8 | 88.33 | 91.45 | 94.25 | 89.37 | 93.77 | 95.33 | 90.65 | 95.33 | 95.55 |

| 1:16 | 85.41 | 90.71 | 92.89 | 86.70 | 92.21 | 93.77 | 87.54 | 93.15 | 93.93 |

| 1:32 | 83.23 | 89.77 | 91.95 | 83.88 | 90.65 | 92.83 | 84.42 | 91.90 | 93.46 |

| BKB | |||||||||

| 1:200 | 86.97 | 86.04 | 89.72 | 89.19 | 90.66 | 91.67 | 97.25 | 99.99 | 99.99 |

| 1:400 | 82.20 | 85.94 | 87.72 | 87.20 | 89.68 | 90.77 | 95.16 | 99.46 | 99.99 |

| 1:800 | 79.25 | 82.10 | 84.80 | 83.61 | 86.80 | 87.90 | 92.53 | 96.53 | 97.83 |

| 1:1600 | 75.80 | 81.30 | 83.20 | 82.29 | 83.30 | 85.20 | 90.25 | 95.72 | 96.72 |

| CGS | |||||||||

| 1:200 | 97.32 | 98.53 | 98.98 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| 1:400 | 95.09 | 97.71 | 98.61 | 99.99 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| 1:800 | 94.72 | 95.05 | 96.50 | 99.92 | 99.99 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| 1:1600 | 88.48 | 94.41 | 95.76 | 99.86 | 99.84 | 99.84 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| G-DDB | |||||||||

| 1:200 | 96.21 | 97.26 | 97.46 | 99.99 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| 1:400 | 94.82 | 96.24 | 96.36 | 99.91 | 99.96 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| 1:800 | 94.33 | 94.23 | 95.83 | 99.73 | 99.89 | 99.98 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| 1:1600 | 85.82 | 92.14 | 93.57 | 98.53 | 99.71 | 99.90 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| PMBC | |||||||||

| 1:200 | 96.87 | 97.28 | 98.32 | 99.99 | 99.99 | 99.99 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| 1:400 | 95.32 | 96.52 | 97.53 | 99.94 | 99.94 | 99.99 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| 1:800 | 92.56 | 94.12 | 96.82 | 99.82 | 98.84 | 99.46 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| 1:1600 | 84.32 | 91.83 | 93.02 | 99.47 | 98.58 | 99.19 | 95.28 | 97.82 | 99.98 |

| Group | Item | Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 3 | Day 4 | Day 5 | Day 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PMBC | Bacterial Count Before Disinfection (106 cfu/mL) | 1.55 ± 0.82 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Bacterial Count After Disinfection (106 cfu/mL) | 1.22 ± 0.17 | 1.30 ± 0.73 | 1.54 ± 1.21 | 1.60 ± 0.73 | 1.71 ± 1.70 | 1.74 ± 1.17 | |

| Bacterial Recovery Rate (%) | 21.3 | 83.9 | 99.4 | 103.2 | 110.3 | 112.3 | |

| PMBC + BP | Bacterial Count Before Disinfection (106 cfu/mL) | 2.35 ± 0.17 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Bacterial Count After Disinfection (106 cfu/mL) | 1.82 ± 0.17 | 1.92 ± 2.56 | 2.48 ± 1.70 | 2.69 ± 2.23 | 3.00 ± 1.59 | 3.04 ± 1.82 | |

| Bacterial Recovery Rate (%) | 22.6 | 81.7 | 105.5 | 114.5 | 127.7 | 129.4 | |

| G-DDB | Bacterial Count Before Disinfection (106 cfu/mL) | 3.97 ± 1.25 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Bacterial Count After Disinfection (106 cfu/mL) | 2.00 ± 1.03 | 2.54 ± 1.23 | 3.28 ± 0.83 | 3.62 ± 0.96 | 4.30 ± 1.03 | 4.54 ± 2.83 | |

| Bacterial Recovery Rate (%) | 49.64 | 63.93 | 82.62 | 91.23 | 108.31 | 114.48 | |

| G-DDB + BP | Bacterial Count Before Disinfection (105 cfu/mL) | 9.50 ± 1.01 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Bacterial Count After Disinfection (105 cfu/mL) | 2.00 ± 1.06 | 3.48 ± 2.74 | 4.87 ± 2.96 | 5.74 ± 0.94 | 8.51 ± 1.26 | 9.66 ± 2.31 | |

| Bacterial Recovery Rate (%) | 20.98 | 36.62 | 51.34 | 60.32 | 89.43 | 101.57 | |

| CGS | Bacterial Count Before Disinfection (106 cfu/mL) | 5.56 ± 0.71 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Bacterial Count After Disinfection (106 cfu/mL) | 1.93 ± 1.09 | 3.21 ± 0.31 | 4.79 ± 0.76 | 5.22 ± 2.29 | 5.81 ± 0.74 | 6.29 ± 1.12 | |

| Bacterial Recovery Rate (%) | 34.68 | 57.72 | 86.13 | 93.02 | 104.54 | 113.33 | |

| CGS + BP | Bacterial Count Before Disinfection (106 cfu/mL) | 4.09 ± 1.14 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Bacterial Count After Disinfection (106 cfu/mL) | 0.56 ± 0.34 | 1.94 ± 0.98 | 2.81 ± 1.43 | 3.93 ± 2.00 | 4.32 ± 2.20 | 4.49 ± 2.28 | |

| Bacterial Recovery Rate (%) | 13.72 | 47.47 | 68.73 | 96.12 | 105.74 | 109.92 |

References

- Ramesh, A.; Bailey, E.S.; Ahyong, V.; Langelier, C.; Phelps, M.; Neff, N.; Sit, R.; Tato, C.; DeRisi, J.L.; Greer, A.G.; et al. Metagenomic characterization of swine slurry in a North American swine farm operation. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 16994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán-Luna, P.; Nag, R.; Martínez, I.; Mauricio-Iglesias, M.; Hospido, A.; Cummins, E. Quantifying current and future raw milk losses due to bovine mastitis on European dairy farms under climate change scenarios. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 833, 155149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Tang, X.; Nan, X.; Jiang, L.; Wang, H.; Liu, J.; Yang, L.; Yao, J.; Xiong, B. Nutrition, gastrointestinal microorganisms and metabolites in mastitis occurrence and control. Anim. Nutr. 2024, 17, 220–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, Y.; Gao, Y.; Guo, M.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, G.; Xia, L.; Ma, J.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, H.; Sun, J.; et al. Phage cocktail superimposed disinfection: A ecological strategy for preventing pathogenic bacterial infections in dairy farms. Environ. Res. 2024, 252, 118720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaatout, N.; Ayachi, A.; Kecha, M. Staphylococcus aureus persistence properties associated with bovine mastitis and alternative therapeutic modalities. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2020, 129, 1102–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.M.; Wang, J.L.; Gou, W.Q.; Tian, Y.; Wang, J. Research Progress on Bovine Mastitis Abroad—Based on Web of Science Core Database. China Dairy Ind. 2023, 89–97. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Vieira, R.; Rodrigues, M.; Santos, P.; Medeiros, N.; Cândido, E.; Rodrigues, N. The effects of implementing management practices on somatic cell count levels in bovine milk. Animal 2021, 15, 100177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germon, P.; Foucras, G.; Smith, E.G.D.; Rainard, P. INVITED REVIEW: Mastitis Escherichia coli strains: Mastitis-Associated or Mammo-Pathogenic? J. Dairy Sci. 2025, 108, 4485–4507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomanić, D.; Samardžija, M.; Kovačević, Z. Alternatives to Antimicrobial Treatment in Bovine Mastitis Therapy: A Review. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, K.; Godden, S.; Royster, E.; Crooker, B.; Timmerman, J.; Fox, L. Relationships among bedding materials, bedding bacteria counts, udder hygiene, milk quality, and udder health in US dairy herds. J. Dairy Sci. 2019, 102, 10213–10234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maillard, J.-Y.; Pascoe, M. Disinfectants and antiseptics: Mechanisms of action and resistance. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 22, 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, A.M.; Teska, P.J.; Lineback, C.B.; Oliver, H.F. Strain, disinfectant, concentration, and contact time quantitatively impact disinfectant efficacy. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2018, 7, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klarczyk, B.; Ruffert, L.; Ulatowski, A.; Mogrovejo, D.; Steinmann, E.; Steinmann, J.; Brill, F. Evaluation of temperature, drying time and other determinants for the recovery of Gram-negative bacterial pathogens in disinfectant efficacy testing. J. Hosp. Infect. 2023, 141, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Chung, H.; Lee, H.; Myung, D.; Choi, K.; Kim, S.; Htet, S.L.; Jeong, W.; Choe, N. Evaluation of the disinfectant concentration used on livestock facilities in Korea during dual outbreak of foot and mouth disease and high pathogenic avian influenza. J. Vet. Sci. 2020, 21, e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klaas, I.C.; Zadoks, R.N. An update on environmental mastitis: Challenging perceptions. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2018, 65 (Suppl 1), 166–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Dong, F.; Sun, W.K.; Zhao, K.Y.; Yang, B.; Cui, S.Y. Interpretation of the Standard for Evaluation of On-site Disinfection (WS/T 797-2022). J. Environ. Hyg. 2022, 12, 634–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 38502-2020; Laboratory Test Methods for Bactericidal Efficacy of Disinfectants. China Zhijian Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2020.

- Tripathi, A.; Park, J.; Pho, T.; Champion, J.A. Dual Antibacterial Properties of Copper-Coated Nanotextured Stainless Steel. Small 2024, 20, e2311546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, L.-Y.; Lee, S.-Y.; Park, J.; Hong, S.-W.; Daniel, K.F.; Jeong, H.-H.; Lee, I.-B. Improving spray performance of vehicle disinfection systems in livestock farms using computational fluid dynamics analysis. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 215, 108435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.M.; Kwon, S.J.; Jiang, B.H.; Choi, E.H.; Park, G.; Kim, K.M. The antibacterial effect of non-thermal atmospheric pressure plasma treatment of titanium surfaces according to the bacterial wall structure. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pokhrel, R.; Shakya, R.; Baral, P.; Chapagain, P. Molecular Modeling and Simulation of the Peptidoglycan Layer of Gram-Positive Bacteria Staphylococcus aureus. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2022, 62, 4955–4962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senchenkova, N.S.; Hou, W.; Naumenko, I.O.; Geng, P.; Shashkov, A.S.; Perepelov, A.V.; Yang, B.; Knirel, Y.A. Structure and genetics of a glycerol 2-phosphate-containing O-specific polysaccharide of Escherichia coli O33. Carbohydr. Res. 2018, 460, 47–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medina, C.; Manriquez, D.; Gonzalez-Córdova, B.; Pacha, P.; Vidal, J.; Oliva, R.; Latorre, A. Biofilm Forming Ability of Staphylococcus aureus on Materials Commonly Found in Milking Equipment Surfaces. J. Dairy Sci. 2025, 108, 3382–3389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ersoy, G.Z.; Dinc, O.; Cinar, B.; Gedik, S.T.; Dimoglo, A. Comparative evaluation of disinfection mechanism of sodium hypochlorite, chlorine dioxide and electroactivated water on Enterococcus faecalis. LWT 2018, 102, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Nitin, N. Antimicrobial Particle-Based Novel Sanitizer for Enhanced Decontamination of Fresh Produce. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2019, 85, e02599-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeon, J.; Jung, S. Effects of temperature and solution composition on evaporation of iodine as a part of estimating volatility of iodine under gamma irradiation. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 2017, 49, 1689–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Yang, Y.; Wei, J.; Xu, J.; Li, J.; Wang, P.; Xu, J.; Han, Y.; Jin, H.; Jin, D.; et al. Cobalt ferrites/activated carbon: Synthesis, magnetic separation and catalysis for potassium hydrogen persulfate. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2019, 249, 114420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, B.; Zhao, K.; Li, X. Application research of nano-storage materials in cold chain logistics of e-commerce fresh agricultural products. Results Phys. 2019, 13, 102049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahfouz, R.A.; Nada, G.H.; Magar, S.H.; ElBaghdady, K.Z.; Hassan, R.Y. Nano-biosensors for rapid detection of antibiotic resistance genes blaCTX-M in Escherichia coli and blaKPC in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 310 Pt 2, 143216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, M.A.; Zadoks, R.N. Methicillin resistant S. aureus in human and bovine mastitis. J. Mammary Gland. Biol. Neoplasia 2011, 16, 373–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzoli, F.; Turchi, B.; Pedonese, F.; Torracca, B.; Bertelloni, F.; Cilia, G.; Cerri, D.; Fratini, F. Coagulase negative staphylococci from ovine bulk-tank milk: Effects of the exposure to sub-inhibitory concentrations of disinfectants for teat-dipping. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2021, 76, 101656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, D.; Rahman, A.; Hu, H.; Jensen, S.; Deva, A.; Vickery, K. Effect of disinfectant formulation and organic soil on the efficacy of oxidizing disinfectants against biofilms. J. Hosp. Infect. 2019, 103, e33–e41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeLeo, C.P.; Huynh, C.; Pattanayek, M.; Schmid, K.C.; Pechacek, N. Assessment of ecological hazards and environmental fate of disinfectant quaternary ammonium compounds. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2020, 206, 111116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Disinfectant Abbreviation | Main Component(s) | Dilution Ratio (mg/L) | Neutralizer |

|---|---|---|---|

| PVP-I | 5% Iodine | 156.25~1250 | 0.1% Sodium Thiosulfate Solution |

| BKB | 5% Benzalkonium Bromide | 31.25~250 | 3% Tween 80 |

| CGS | 15% Glutaraldehyde + 10% Benzalkonium Chloride | 62.5~500 | 3% Tween-80 + 0.5% Lecithin + 0.3% Glycine |

| G-DDB | 5% Glutaraldehyde + 5% Didecyldimethylammonium Bromide | 62.5~500 | 3% Tween-80 + 0.5% Lecithin + 0.3% Glycine |

| PMBC | Available Chlorine ≥ 10% | 62.5~500 | 2% Tween-80 + 0.1% Lecithin + 0.5% Sodium Thiosulfate |

| Disinfectant Abbreviation | E. coli/(107 CFU/mL) | Error Rate (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | Group 4 | Group 5 | Group 6 | ||

| PVP-I | 0 | 8 | 1.66 | 1.87 | 1.70 | 0 | 4.84 |

| BKB | 0 | 9 | 1.70 | 1.73 | 1.68 | 0 | 1.04 |

| CGS | 0 | 9 | 1.32 | 1.21 | 1.67 | 0 | 12.86 |

| G-DDB | 0 | 11 | 1.24 | 1.08 | 1.40 | 0 | 8.60 |

| PMBC | 0 | 8 | 1.54 | 1.87 | 1.56 | 0 | 8.58 |

| Pathogenic Microorganism | MIC Value (Dilution Ratio) of Disinfectants | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PVP-I | PMBC | BKB | CGS | G-DDB | |

| E. coli | 1:8 | 1:800 | 1:1280 | 1:3840 | 1:2400 |

| S. aureus | 1:8 | 1:800 | 1:1280 | 1:3840 | 1:2400 |

| Pathogenic Microorganism | MIC Value (Dilution Ratio) of Disinfectants | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PVP-I | PMBC | BKB | CGS | G-DDB | |

| E. coli | 1:4 | 1:400 | 1:160 | 1:640 | 1:480 |

| S. aureus | 1:4 | 1:400 | 1:160 | 1:640 | 1:480 |

| Group | Immediate Disinfection Efficiency (%) | Persistence Days (days) | 6-Day Bacterial Count Increase Ratio | Overall Efficacy Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CGS + BP | 86.28 | 5 | 7.98 | 1 |

| G-DDB + BP | 79.02 | 6 | 4.83 | 2 |

| CGS alone | 65.32 | 5 | 3.26 | 3 |

| G-DDB alone | 50.36 | 5 | 2.27 | 4 |

| PMBC alone | 21.30 | 4 | 1.43 | 5 |

| PMBC + BP | 22.60 | 3 | 1.67 | 6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, T.; Fan, H.; Chai, M.; He, T.; Li, Y.; Han, X.; Li, Y.; Bai, H.; Jiang, S. Study on the Disinfection Efficacy of Common Commercial Disinfectants in China Against Mastitis-Causing Pathogens and Bedding Materials in Large-Scale Dairy Farms. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 1072. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci12111072

Wang T, Fan H, Chai M, He T, Li Y, Han X, Li Y, Bai H, Jiang S. Study on the Disinfection Efficacy of Common Commercial Disinfectants in China Against Mastitis-Causing Pathogens and Bedding Materials in Large-Scale Dairy Farms. Veterinary Sciences. 2025; 12(11):1072. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci12111072

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Tianchen, Haoyu Fan, Mengqi Chai, Tao He, Yongqi Li, Xiangshu Han, Yanyang Li, Hangfei Bai, and Song Jiang. 2025. "Study on the Disinfection Efficacy of Common Commercial Disinfectants in China Against Mastitis-Causing Pathogens and Bedding Materials in Large-Scale Dairy Farms" Veterinary Sciences 12, no. 11: 1072. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci12111072

APA StyleWang, T., Fan, H., Chai, M., He, T., Li, Y., Han, X., Li, Y., Bai, H., & Jiang, S. (2025). Study on the Disinfection Efficacy of Common Commercial Disinfectants in China Against Mastitis-Causing Pathogens and Bedding Materials in Large-Scale Dairy Farms. Veterinary Sciences, 12(11), 1072. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci12111072