1. Introduction

The dairy sector faces many challenges due to societal pressure to handle the negative environmental effects of dairy production. A reduction in the number of dairy farms and increasing herd sizes have become global trends over recent decades [

1], thus impacting the sector’s development. Increases in herd size are characterized by the farm’s transformation from a family labor-driven farm to the need for hired labor—often immigrants in the industrialized world [

2]. In the period when the dairy farms’ structure changed, the dairy veterinarian tasks changed from individual animal treatment to proactive herd health management [

3,

4].

During this period, dairy veterinarian-initiated herd health services and preventive veterinary medicine shifted from the traditional approach of reactive ‘firefighter’ work and drug distribution [

3]. This third phase was characterized by a shift from reactive to proactive involvement of the herd veterinarian, as dairy farmers recognized that increased herd performance was linked to monitoring and reducing the negative impact of subclinical disease. Dairy veterinarian-initiated herd health services and preventative veterinary medicine changed in that period from the historical approach of firefighter work and distributing drugs [

5].

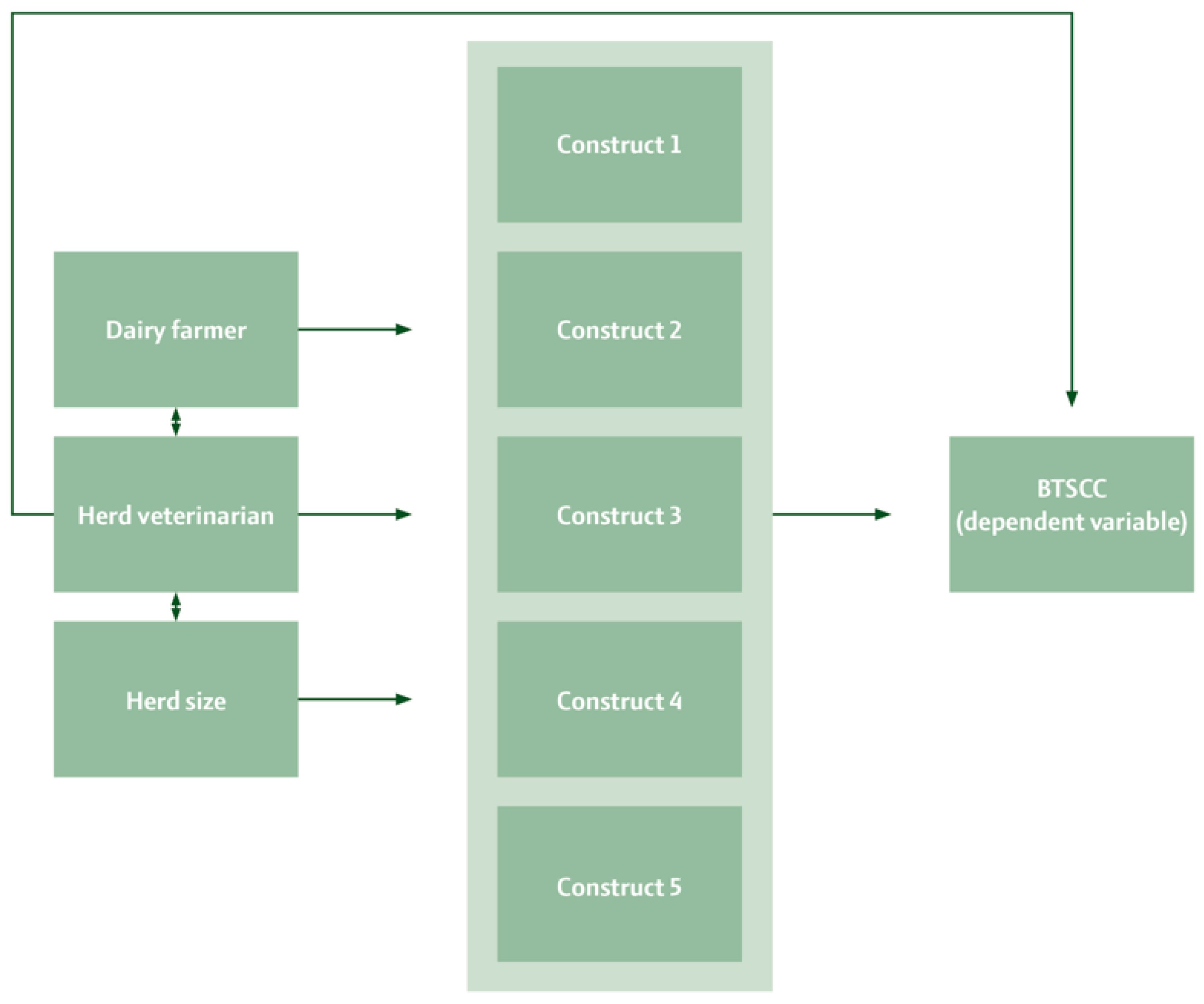

As a result, the dairy veterinarian of today needs a comprehensive soft-skills toolbox with a variety of skills that may be very different from the traditional veterinary college curriculum to have an impact on the bulk tank somatic cell count (BTSCC) as a measure of udder health [

6,

7]. The herd veterinarian must acknowledge and understand the dairy farmer’s aim—whether to eradicate disease, increase production, or achieve other goals [

8]. The increase in the production level may also increase the incidence of production-related diseases (Gröhn et al. (1995)) [

9], and dairy veterinarians today therefore need an economic mindset to allow them to focus on the costliest production diseases in dairy cows [

10].

Dairy veterinarians must therefore be skilled in interpersonal communication at different operational levels and frequently in a foreign language to accommodate different owners and a diverse labor force. Evidence shows that the involvement and respect of experience in relations between patients or clients improve consultancy quality in human and veterinary medicine [

11,

12]. Also well described in the literature is the use of motivational interviews by Bard et al. (2018) and Svensson et al. (2020) [

13,

14], which can be another add-on approach to improving communication. Therefore, the herd veterinarian needs to adapt to what is regarded as necessary by the dairy farmer (Kristensen and Enevoldsen (2008)) [

15] and balance the time each of the two parties participates in the mutual discussion during the general herd health consulting [

16]. All these factors have been identified as essential to reaching the overall goal in herd health programs, where association with improved performance, e.g., milk production and BTSCC, was an expected outcome [

17]. Researchers have focused on different ways to implement knowledge at dairy farms, mainly within udder health consulting, to facilitate this development. One approach has been the “stable school”, where farmer-to-farmer communication catalyzes the implementation of changes [

18]. In terms of communication between dairy farmers and dairy veterinarians, previous studies have identified some challenges, with a client group that dairy veterinarians typically regard as “hard to reach” when they are focused on improving udder health on the farm [

19]. However, most dairy farmers acknowledge the herd veterinarian is a crucial partner in udder health consulting [

7]. Therefore, the successful herd veterinarian must identify herd-specific goals and targets and ensure that communication is tailored to the specific dairy farmer (Jansen et al. (2010)) [

20], while considering the farmer’s aim and values. As recommended by Bard et al. (2028) [

13], trust, shared understanding between the dairy farmer and herd veterinarian, and the meaningful interpretation of advice are critical factors for motivating change. Therefore, good consulting consists of several elements e.g., herd-specific goals, tailored communication, trust, and understanding, and to ensure this, we need to address the level of agreement between the dairy farmer and the herd veterinarian.

Nevertheless, to our knowledge, no previous studies have aimed to determine the level of agreement between dairy farmers and herd veterinarians in the mutual communication during udder health consulting and how this may affect BTSCC. The expected results can be utilized to target the future training and communication between the dairy farmer and the herd veterinarian, with the benefit of improved mutual communication between the stakeholders involved.

Therefore, this study aims to determine the agreement in mutual communication between dairy farmers and herd veterinarians working with udder health consulting in Denmark, where the agreement in communication affects the BTSCC. Ideally, the dairy farmer and herd veterinarian relationship is built on mutual trust and an alignment of expectations; therefore, we hypothesize that the agreement would be at least minor to moderate, and the association with BTSCC will be minor. Specifically, the study aims to investigate two critical questions: What is the level of agreement between dairy farmers and herd veterinarians in terms of their perception of mutual communication when it comes to udder health? Does the level of agreement in mutual communication between the herd veterinarian and dairy farmer affect the BTSCC.

3. Results

The descriptive statistics were first calculated; there were four herd veterinarians answering the questionnaire on request, and one was incomplete because the herd veterinarian had never discussed udder health at the farm. Finally, one herd veterinarian had herd health contracts with two different dairy farms enrolled in the study. We enrolled dairy farmers and herd veterinarians from the same herds, and the response levels were high, with 100% of dairy farmers participating at the time of our visit, but the herd veterinarians also had a high questionnaire return rate of 94%. The first author verified the answers but did not address potential missing values at the visit. No illogical answers were recorded because the categories for answers were fixed.

The herds enrolled ranged from 105 to 1291 cows, with a mean herd size of 326 milking cows. There were three milking years per culled cow, calculated from first calving to leaving the herd as a culled cow, and a rolling average of 11,774 L of energy-corrected milk. The mean, median, and quartiles of the farm-level geometric mean BTSCC were then calculated, with the results shown in

Table 1.

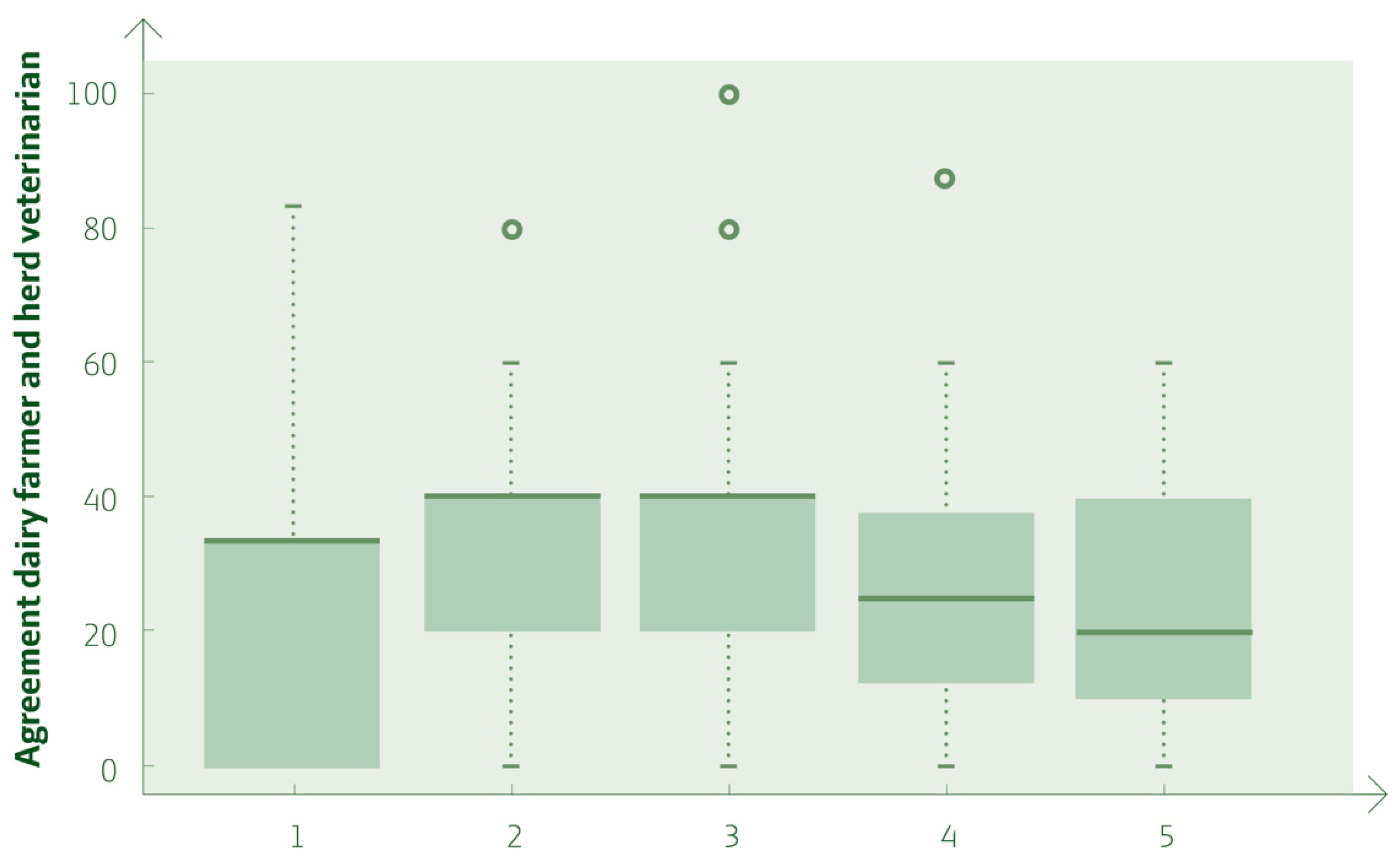

The minimum and maximum agreement values of each of the five constructs are illustrated in

Figure 2.

The herd veterinarians visited the farms every 1–3 weeks according to legislation and depending on the herd size. The perception data included are from questionnaires collected from (n = 88) dairy farmers and (n = 84) veterinarians.

The complete output from testing Cohen’s weighted kappa value for paired questions can be found in the

Supplementary Material Table S3. As a summary, the agreement between dairy farmers and herd veterinarians regarding communication for each paired question is graphically illustrated in

Figure 3. The agreement ranged between −0.06 and 0.12, indicating no to slight agreement, which was lower than the expected moderate agreement.

This suggests that the dairy farmers and herd veterinarians perceived the communication of the udder health consultation quite differently.

There were a few differences between farmer and veterinarian answers in the constructs, as illustrated in

Figure 2. From the dairy farmers’ perspective, in question pair two, representing “To what extent do you agree that there is an opportunity for fruitful discussion between the farmer and herd veterinarian, with time for reflection during the meeting?” (

Supplementary Table S2), the agreement was −0.06. With an agreement at 0.12, question pair 22, “To what extent do you agree that mastitis is a serious problem in the herd, bearing in mind the sector’s target of reducing antibiotic consumption” (

Supplementary Table S3), had the highest agreement in the study.

An important result was the factors associated with udder health, represented by the BTSCC, here in

Table 2, the full and the final model can be seen. After the calculations, constructs, C1, C3, and C5 (

Supplementary Tables S1 and S2) were eliminated, as well as herd size.

The coefficient for construct (2), the frequency with which udder health is discussed and how potential problems are identified, was negative; every unit agreement increase was associated with a 427 cells/mL lower BTSCC. In contrast, for construct (4), general cooperation between the dairy farmer and herd veterinarian, in investigating the understanding and relationship between them, the coefficient was positive but small; one-unit higher agreement between the dairy farmer and herd veterinarian was associated with a 604 cells/mL higher BTSCC.

4. Discussion

To continuously improve communication between dairy farmers and their herd veterinarians, we first need to obtain the present status. Therefore, we assessed the agreement between the dairy farmers and herd veterinarians’ perception of the mutual communication during udder health consultation and found no to slight agreement (Fleiss (1981)) [

23], which was between −0.06 and 0.12. This finding was in contrast with our expectations that the agreement would be at least moderate to have a working relationship between the dairy farmer and herd veterinarian. Good consulting from the herd veterinarian consists of several elements, e.g., herd-specific goals, tailored communication, trust, and understanding; therefore, we analyzed the level of agreement. In other areas of veterinary medicine, successful communication has been linked to quality (Abood (2008), Churchill and Ward (2016)) [

24,

25]; therefore, we associated the agreement in perceived communication with the actual BTSCC on a farm.

In conducting this type of research, it is always a challenge to prevent self-reporting bias in a questionnaire, where the respondents potentially rate themselves higher, especially in areas with adverse effects [

26,

27]. This issue must be considered when assessing the agreement. A second challenge in self-reporting questionnaires is the impact of negative mood states in the past two weeks prior to answering the questionnaire [

28]. This potential bias in answering must be considered because we focus on asking about the most recent visit from the herd veterinarian to avoid the risk of recall bias. Thus, we wanted to focus on the degree to which they agreed and whether certain areas would indicate agreement to monitor the status and highlight whether and potentially where improvement was needed. There can also be some contextual differences between the two groups of respondents, which impact the distribution of answers and, therefore, the level of agreement. This point can be affected by the different educational backgrounds of dairy farmers and herd veterinarians, social norms and values, and social influence from other peer groups. The respondents’ personalities also impact the responses, where some will choose extreme responses such as “strongly agree” or “strongly disagree”, potentially leading to low agreement. Also, here, the dairy farmer has to relate only to the herd veterinarian and only one person; the herd veterinarian is also asked about the specific dairy farmer. However, the herd veterinarian has a group of farmers they service; therefore, they could risk providing answers of more general opinion.

Construct 2 was found to have a confidence interval of the estimate overlapping with zero. This indicates that this variable could be insignificant. Still, it was kept in the final model by the backwards model selection procedure using AIC. Further studies should address this because a small but consistent effect might have a CI that overlaps with zero if the effect size is too small to be reliably distinguished from zero due to high variability or limited precision.

The question pair with the least agreement was question pair 2, which was a personal question regarding satisfaction: “To what extent do you agree that there is an opportunity for fruitful discussion between the dairy farmer and herd veterinarian, with time for reflection during the meeting?”. Because we have this low level of agreement, we need to reflect on the extreme values in trying to understand the challenges in communication between the dairy farmer and the herd veterinarian. It seems like we need to work with the frame of the meeting—because the discussion lacks mutual understanding. The meeting is set, and the topic discussed is the udder health, but they do not discuss it out of a common understanding of the aims and goals of the dairy farmer.

In contrast, question pair 22 had the highest agreement, where the question was more general regarding antimicrobials: “To what extent do you agree that clinical mastitis in cows requires excessive resources and time from the farm employees?” (

Supplementary Table S3). The latter question, which received the highest level of agreement, is more technical in nature and likely easier for participants to agree on. In this context, both dairy farmers and herd veterinarians are less influenced by personal feelings, preferences, or individual personalities regarding the goals and objectives for the dairy herd. Instead, their shared practical experience in managing sick cows allows them to readily understand the complexities of diagnosing, treating, and handling waste milk, which is often viewed as an inconvenient disruption to the daily routine. And this point about the disruption is important, because continuity is very important in milk production to ensure the allocation of enough resources in terms of employees at any given time.

Handling antimicrobials was described by Gröndal et al. (2023) [

29], where prescribing antimicrobials for dairy cattle needs to be understood as taking form in a relationship in which both veterinarians and farmers take an active part. This can be a reason for the level of agreement.

The scope of the seven-point Likert scale challenged the likelihood that the dairy farmer and herd veterinarian have the exact same answer to their perception of communication in udder health consulting at a specific dairy farm, but this was overcome with the weight of the answers. Other researchers found that the herd veterinarian’s perceived skills were not equal to those desired by the dairy farmer [

30]. Here, the herd veterinarian could implement the motivational interview to improve agreement, which would be beneficial to improving the overall communication during consulting [

31]. However, the perspectives of the dairy farmer and the dairy veterinarian still differ because their starting point for conversation differs. We did not expect complete agreement, but a discrepancy of this magnitude was unexpected.

The multivariable analysis for associating BTSCC with constructs representing agreement on communication in udder health consulting showed that monitoring DHI data related to udder health and regular follow-up by the herd veterinarian in construct (2) “The frequency with which udder health is discussed and how potential problems are identified” were associated with a significantly lower BTSCC of 427 cells/mL. This agreement was expected because the role of monitoring has long been seen as necessary: “Udder health monitoring is an essential part of preventive veterinary medicine [

6]. Another significant factor associated with BTSCC is the agreement between dairy farmers and herd veterinarians in construct (4), general cooperation between the dairy farmer and herd veterinarian, in investigating the understanding and relationship between them; more cooperation was associated with a 604 cells/mL higher BTSCC.

This result is, on one hand, counterintuitive but like the findings of Stevens et al. (2019) [

32], who found increased new infection rates in the herds with increased veterinary intervention. Conversely, dairy farmers with more udder health problems may cooperate more to solve these issues. Therefore, we need to consider plausible explanations to interpret the findings of increased cooperation and high BTSCC, such as (1) a recent acute clinical mastitis problem encouraged the farmers to seek advice from the herd veterinarian, (2) the dairy farmers are in the process of improving the BTSCC and therefore feel confident and recognize the value created by the herd veterinarian, or (3) the dairy farmer or the herd veterinarian over- or underestimate the advice. It is evident from the present analysis that the herd veterinarians may not be fully aware of the farmers’ aims and targets. This observation agrees with Derks et al. (2012) [

33], who found that dairy veterinarians providing services in herd health programs did not sufficiently align with the dairy farmer regarding goal-setting and evaluation. This makes it difficult to solve potential herd-specific problems and add value to the dairy farm. It is, of course, easy to point at the herd veterinarian, who must be proactive in providing the service. Yet, it is also essential to consider how skilled the farmer is in defining their own needs and be instrumental in implementing the herd-specific advice from the herd veterinarian.

Thus, from a business perspective, the dairy farmer should select a herd veterinarian who is skilled and capable of suggesting interventions to solve problems, focus on communication (Derks et al. (2012)) [

33], and use communication methods like motivational interviewing for improved implementation [

34]. This points to self-reflection for the herd veterinarians who want to be the preferred dairy consultant in the future and adapt their communication style towards the dairy farmer’s needs [

31]. Herd veterinarians will face more challenges due to the development of larger farms, more hired staff, and several management levels. As a result, herd health veterinarians must act as integrated team members and be able to adapt their communication style, motivation, and operational effort to each dairy farmer they work with. In that context, other researchers have suggested four categories of dairy farmers (Jansen et al. (2010)) [

19]: proactivists, do-it-yourselfers, wait-and-see-ers, and reclusive traditionalists, but we still need more insight into how we can successfully approach each type. The herd veterinarian needs to consider the different kinds of dairy farmers to target how they approach their problems. Effective communication will only become more important because even though automation and the increased application of milking robots and sensor technology will remove the need to align with some operational staff, clear communication and establishing specific and realistic goals with the dairy farmer is still essential. The dairy farmer expects value for money when involving the herd veterinarian, and the herd veterinarian must continuously offer herd-specific solutions to add value to the dairy farm. However, farmers differ in their opinions and behavior, and we therefore expected variation in the “Cooperation with the herd veterinarian” construct regarding the level of agreement. The five constructs also differ in importance.

Of the constructs with no significant outcome, it was interesting that a SMART action plan was not associated with better udder health. Thus, the herd veterinarians should try to identify the dairy farmers’ clear and well-considered vision for improving udder health consultation and deal with dairy farmers individually. The well-informed dairy farmers only need support from the sideline with motivation and knowledge upon request. In contrast, the herd veterinarian must suggest goals and actions for the less informed farmers and provide more operational support. Researchers such as Kupier et al. (2005) [

7] found that the herd veterinarian is an essential partner for the dairy farmer, and we anticipated that the dairy farmer and herd veterinarian would regularly discuss and align expectations regarding udder health consulting.

However, our analysis demonstrated a wide variation in opinion about the communication between farmers and their veterinarians during udder health consulting. The current study included (n = 88) dairy farmers and their consulting herd veterinarians, compromising the study’s statistical power. Other studies, such as Jansen et al. (2010) [

19] had (n = 25) dairy farmers enrolled: Falkenberg et al. (2019) [

35], with (n = 33) dairy participating veterinarians, and Bard (2018) [

13], where (n = 14) dairy farmers and their corresponding herd veterinarians were interviewed. However, there is a difference in how the data were collected in the cited studies; they were based on interviews, whereas the present study is based on closed-end questions in a questionnaire. The studies based on semi-structured open-ended questions are beneficial for a more explorative approach, where other topics than the data from the present study can be retrieved.

Another challenge of this study could be the choice of Likert scale steps in monitoring agreement; yet, research has shown that questionnaires become less accurate when the scales include less than four and more than seven points [

36]. We therefore chose Likert scale questions with answers in five to seven steps in accordance with other studies on mastitis and udder health consulting [

32]. The scale is sensitive to a single-unit difference in answer, but weighting was used to compensate for this. The high level of response allowed us to analyze the impact of perception at the herd level and helped reveal a low level of agreement.

Based on our analysis, it is evident that there is a need to rethink the collaboration between dairy farmers and herd veterinarians in the operationalization of udder health management at the herd level. From the perspective of the herd veterinarian, there is significant potential for more active engagement with communication strategies that have been empirically shown to be effective, such as motivational interviewing [

31]. This evidence-based technique emphasizes empathetic listening, active engagement, and maintaining a non-judgmental stance. Motivational interviewing fosters a collaborative dynamic where the focus is on resolving ambivalence and enhancing the individual’s intrinsic motivation to embrace change [

37].

However, the successful implementation of this approach hinges on the clarity of the dairy farmer’s objectives and the establishment of interventions framed within a SMART action plan [

38]. By aligning goals and interventions in a well-defined, structured manner, the SMART approach not only ensures that the aim is clear but also facilitates the allocation of shared responsibilities between the farmer and the herd veterinarian. This communication strategy represents a positive shift toward more effective collaboration, where the veterinarian’s guidance is paired with a clear roadmap that drives accountability and tangible outcomes.

In the current study, several limitations must be considered when interpreting the results. First, there may be over- or under-reporting, as some respondents might feel a social responsibility to provide confident answers, particularly in the context of the customer–service provider relationship. Additionally, some respondents may prefer extreme statements on the Likert scale, which could skew the results. Lastly, selection bias based on the inclusion criteria may also be present—for example, dairy farmers using robotic milking systems might have different perspectives than those who do not.

A follow-up study could address some of these issues by incorporating triangulation, such as through personal interviews or focus groups, to add additional data and perspectives. Observational studies, which rely less on subjective self-reports, offer an alternative method for data collection and could help reduce many of the biases associated with self-reporting, as seen in the current study.

All through the limitations, this study fills a gap in the current literature and has contributed new knowledge to help improve the quality of udder health consulting.