An Exploratory Research Regarding Greek Consumers’ Behavior on Wine and Wineries’ Character

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Size

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Design of the Questionnaires

- (a)

- The first part included questions about the profile and general information about the company.

- (b)

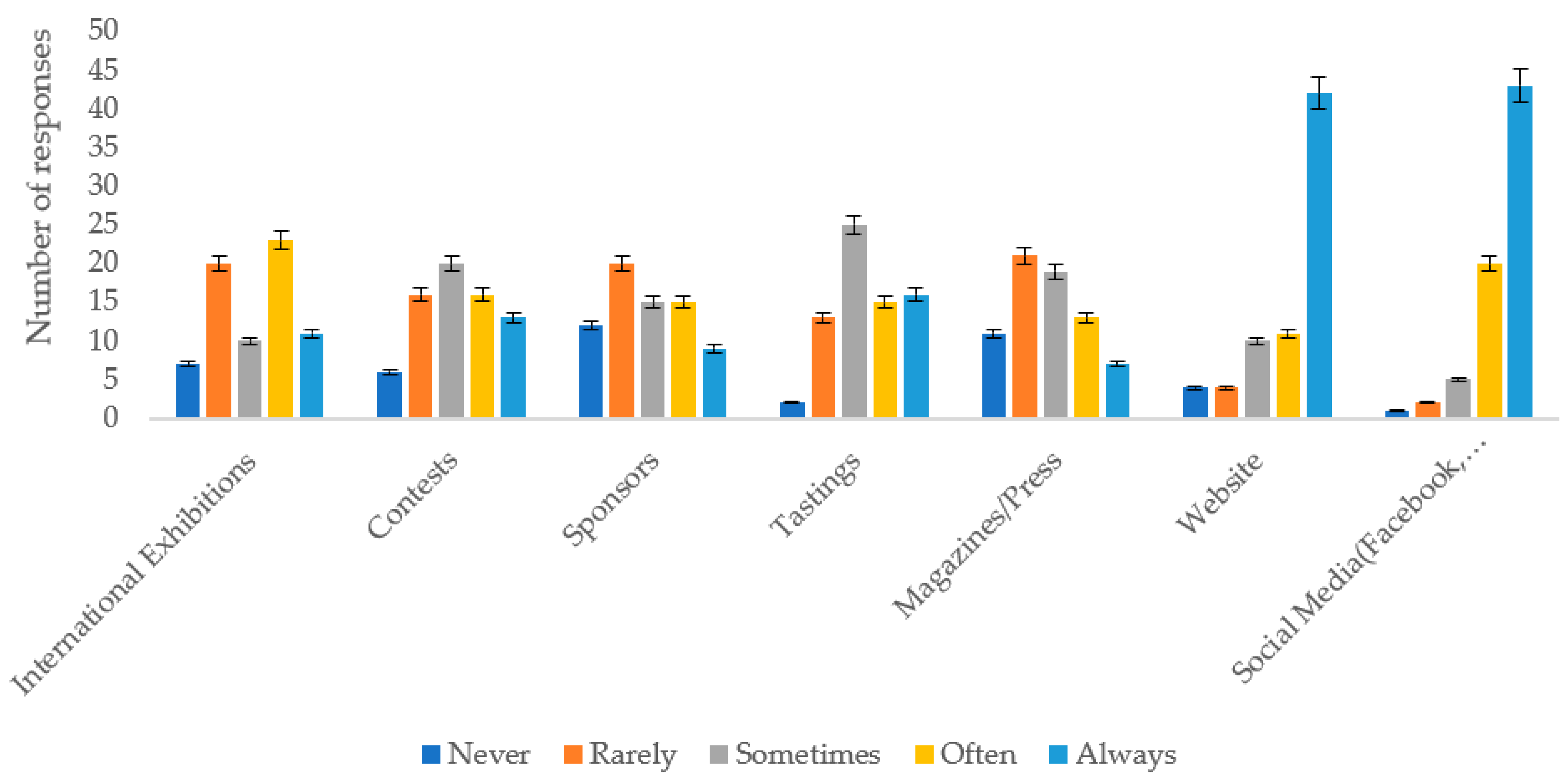

- The second part consisted of questions related to the export activity of the company, competitiveness, and advertising.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

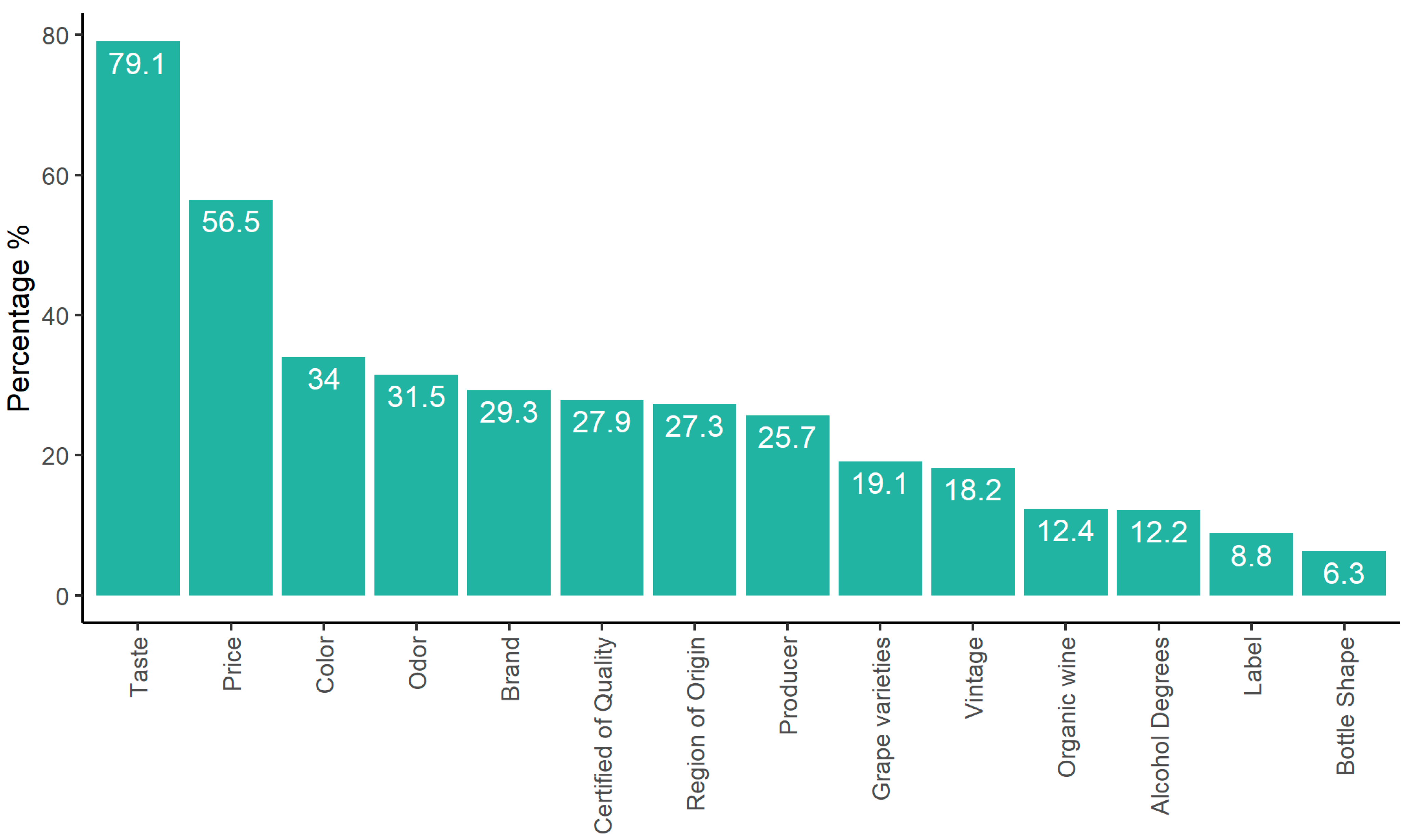

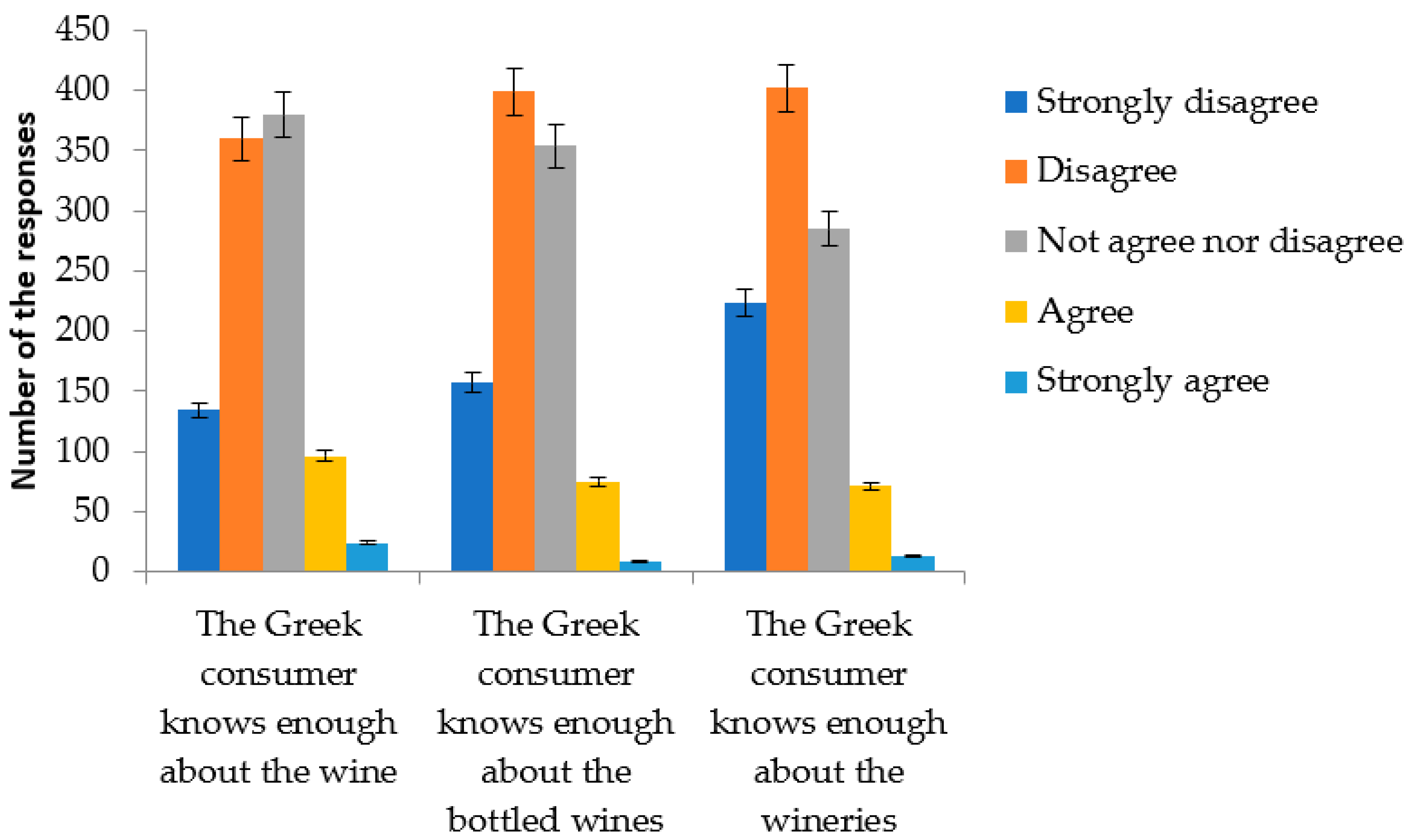

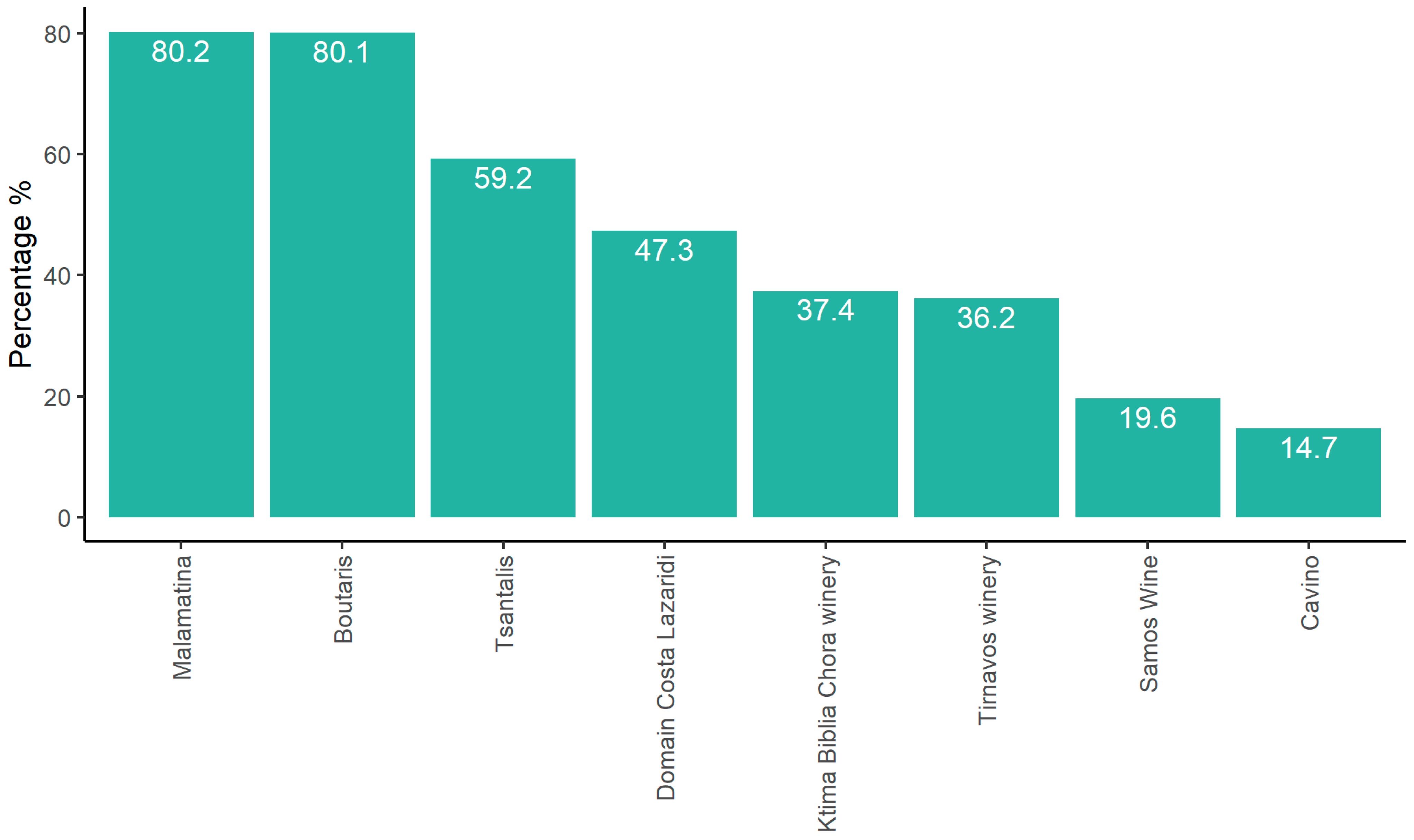

3.1. Consumers’ Data

3.2. Wineries Data

4. Discussion

5. Limitations and Strengths

6. Conclusions and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Greek alcoholic beverage produced by distillation of the residual from winemaking, mostly the marc. Tsipouro is bottled after dilution with water to obtain a product of alcohol content between 37.5% and 50% vol. [51]. |

| 2 | Greek anise-flavored alcoholic beverage produced by distillation of grapes containing with 40–50% alcohol by volume [52]. |

| 3 | Resinated wine with the use of resin as additive mainly from Aleppo pine resin. Retsina follows the same winemaking technique of white or rose [53]. |

| 4 | Spirit produced by double distillation of suma or suma mixed with agricultural-based ethanol and flavored with aniseed (Pimpinella anisum). Suma is produced mainly from raisins, molasses and/or grape must and is a distillate with a maximum 94.5% ethanol content [54]. |

References

- McGovern, P.E.; Fleming, S.J.; Katz, S.H. (Eds.) The Origins and Ancient History of Wine (Food and Nutrition in History and Anthropology Series No. 11); Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ridley, W.; Luckstead, J.; Devadoss, S. Wine: The Punching Bag in Trade Retaliation. Food Policy 2022, 109, 102250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sáenz-Navajas, M.P.; Avizcuri, J.M.; Ballester, J.; Fernández-Zurbano, P.; Ferreira, V.; Peyron, D.; Valentin, D. Sensory-Active Compounds Influencing Wine Experts’ and Consumers’ Perception of Red Wine Intrinsic Quality. LWT 2015, 60, 400–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sáenz-Navajas, M.P.; Campo, E.; Sutan, A.; Ballester, J.; Valentin, D. Perception of Wine Quality According to Extrinsic Cues: The Case of Burgundy Wine Consumers. Food Qual. Prefer. 2013, 27, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäufele, I.; Hamm, U. Organic wine purchase behaviour in Germany: Exploring the attitude-behaviour-gap with data from a household panel. Food Qual. Prefer. 2017, 63, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, J.M.; Sánchez, M. Consumer Preferences for Wine Attributes: A Conjoint Approach. Br. Food J. 1997, 99, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, C.A. When Consumers Buy Wine, What Factors Decide the Final Purchase? Aust. N. Z. Wine Ind. J. 2004, 19, 82–91. [Google Scholar]

- Maicas, S.; Mateo, J.J. Sustainability of Wine Production. Sustainability 2020, 12, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruwer, J.; Saliba, A.; Miller, B. Consumer behaviour and sensory preference differences: Implications for wine product marketing. J. Consum. Mark. 2011, 28, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, D.; Wood, C. Wine: Achieving Competitive Advantage Through Design. Int. J. Wine Mark. 1994, 6, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscovici, D.; Rezwanul, R.; Mihailescu, R.; Gow, J.; Ugaglia, A.A.; Valenzuela, L.; Rinaldi, A. Preferences for eco certified wines in the United States. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2020, 33, 153–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, S.; Szolnoki, G. The relative influence of packaging, labelling, branding and sensory attributes on liking and purchase intent: Consumers differ in their responsiveness. Food Qual. Prefer. 2010, 21, 774–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamzami, L.; Andrini, A.; Budiyati, E. Consumer preferences for a new variety of grapes (Vitis vinifera) paras 61. Ann. Biol. 2020, 36, 159–162. [Google Scholar]

- Famularo, B.; Bruwer, J.; Li, E. Region of origin as choice factor: Wine knowledge and wine tourism involvement influence. Int. J. Wine Bus Res. 2010, 22, 362–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galli, F.; Boger, C.A.; Taylor, D.C. Rethinking luxury for segmentation and brand strategy: The semiotic square and identity prism model for fine wines. Beverages 2019, 5, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orth, U.R.; Malkewitz, K. Holistic package design and consumer brand impressions. J. Mark. 2008, 72, 64–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudreaux, C.A.; Palmer, S. A charming little cabernet: Effects of wine label design on purchase intent and brand personality. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2007, 19, 170–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, N.; Almanza, B.A. Influence of wine packaging on consumers’ decision to purchase. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2006, 9, 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, V.W.; Greatorex, M. Risk reducing strategies used in the purchase of wine in the UK. Eur. J. Mark. 1989, 23, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R.L.; Rao, C.P. The Combined Effects of Brand and Store Reputation on Consumer Perceived Risk and Confidence. In Proceedings of the 1983 Academy of Marketing Science (AMS) Annual Conference; Springer International Publishing: New York City, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 117–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, J.F.; Schiffman, L.G.; Berenson, C. Risk- and Personality-Related Dimensions of Store Choice. J. Mark. 1976, 40, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skuras, D.; Vakrou, A. Consumers’ willingness to pay for origin labelled wine: A Greek case study. Br. Food J. 2002, 104, 898–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caracciolo, F.; Di Vita, G.; Lanfranchi, M.; D’Amico, M. Determinants of sicilian wine consumption: Evidence from a binary response model. Am. J. Appl. Sci. 2015, 12, 794–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, L.M.-C.; Molla-Bauza, M.M.-B.; Gomis, F.J.D.C.; Poveda, A.M. Influence of purchase place and consumption frequency over quality wine preferences. Food Qual. Prefer. 2006, 17, 315–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockshin, L.; Jarvis, W.; d’Hauteville, F.; Perrouty, J.P. Using simulations from discrete choice experiments to measure consumer sensitivity to brand, region, price, and awards in wine choice. Food Qual. Prefer. 2006, 17, 166–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gluckman, R.L. A Consumer Approach to Branded Wines. Eur. J. Mark. 1986, 20, 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruwer, J.; Li, E.; Reid, M. Segmentation of the Australian Wine Market Using a Wine-Related Lifestyle Approach. J. Wine Res. 2002, 13, 217–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capitello, R.; Sirieix, L. Consumers’ perceptions of sustainable wine: An exploratory study in France and Italy. Economies 2019, 7, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amico, M.; Di Vita, G.; Monaco, L. Exploring environmental consciousness and consumer preferences for organic wines without sulfites. J. Clean Prod. 2016, 120, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominici, A.; Boncinelli, F.; Gerini, F.; Marone, E. Consumer preference for wine from hand-harvested grapes. Br. Food J. 2020, 122, 2551–2567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanco, M.; Lerro, M.; Marotta, G. Consumers’ preferences for wine attributes: A best-worst scaling analysis. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunner, T.A.; Siegrist, M. A consumer-oriented segmentation study in the Swiss wine market. Br. Food J. 2011, 113, 353–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amico, M.; Di Vita, G.; Chinnici, G.; Pappalardo, G.; Pecorino, B. Short food supply chain and locally produced wines: Factors affecting consumer behavior. Ital. J. Food Sci. 2014, 26, 329–334. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/2318/1691587 (accessed on 25 March 2019).

- D’Amico, M.; Di Vita, G.; Bracco, S. Direct sale of agro-food product: The case of wine in Italy. Qual.-Access Success. 2014, 15, 247–253. [Google Scholar]

- Chrysochou, P.; Corsi, A.M.; Krystallis, A. What drives Greek consumer preferences for cask wine? Br. Food J. 2012, 114, 1072–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botonaki, A.; Tsakiridou, E. Consumer response evaluation of a greek quality wine. Food Econ. Acta Agric. Scand. Sect. C 2004, 1, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotopoulos, C.; Krystallis, A.; Ness, M. Wine produced by organic grapes in Greece: Using means—End chains analysis to reveal organic buyers’ purchasing motives in comparison to the non-buyers. Food Qual Prefer. 2003, 14, 549–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Organisation of Vine and Wine (OIV). Statistical Report on World Vitiviniculture. Available online: http://www.oiv.int/public/medias/6371/oiv-statistical-report-on-world-vitiviniculture-2018.pdf (accessed on 7 February 2023).

- Tsiakis, T.; Anagnostou, E.; Granata, G.; Manakou, V. Communicating Terroir through Wine Label Toponymy Greek Wineries Practice. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiou, T.; Vrontis, D. Wine Sector Development: A Conceptual Framework Toward Succession Effectiveness in Family Wineries. J. Transnatl. Manag. 2013, 18, 246–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charters, S.; Fountain, J. Younger Wine Tourists: A Study of Generational Differences in the Cellar Door Experience. In Global Wine Tourism: Research, Management and Marketing; Cabi: Wallingford UK, 2006; pp. 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutroupi, E.; Natos, D.; Karelakis, C. Assessing Exports Market Dynamics: The Case of Greek Wine Exports. Procedia Econ Financ. 2015, 19, 184–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Agricultual Information Network. Wine Annual Report and Statistics; USDA Foreign Agricultural Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2012.

- Bruwer, J.; Alant, K. The Hedonic Nature of Wine Tourism Consumption: An Experiential View. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2009, 21, 235–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinography. Social Media and the Wine Industry: A New Era. Available online: https://www.vinography.com/2012/02/social_media_and_the_wine_indu (accessed on 7 February 2023).

- Palmieri, N.; Perito, M.A. Consumers’ willingness to consume sustainable and local wine in Italy. Ital. J. Food Sci. 2020, 32, 222–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, F.; Madureira, T.; Oliveira, J.V.; Madureira, H. The consumer trail: Applying best-worst scaling to classical wine attributes. Wine Econ Policy 2016, 5, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmieri, N.; Perito, M.A.; Macrì, M.C.; Lupi, C. Exploring consumers’ willingness to eat insects in Italy. Br. Food J. 2019, 121, 2937–2950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmieri, N.; Suardi, A.; Pari, L. Italian Consumers’ Willingness to Pay for Eucalyptus Firewood. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmieri, N.; Perito, M.A.; Lupi, C. Consumer acceptance of cultured meat: Some hints from Italy. Br. Food J. 2020, 123, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolopoulou, A.A.; Flouros, A.I.; Demertzis, P.G.; Akrida-Demertzi, K. Differences in Concentration of Principal Volatile Constituents in Traditional Greek Distillates. Food Control 2005, 16, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsarouhas, P.; Papachristos, I. Environmental Assessment of Ouzo Production in Greece: A Life Cycle Assessment Approach. Clean. Environ. Syst. 2021, 3, 100044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, H.; Krausz, S.; Olmer, F.; Mathe, C.; Vieillescazes, C. Analysis of Organic Residues from the Châteaumeillant Oppidum (Cher, France) Using GC–MS. J. Cult. Herit. 2021, 51, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yucesoy, D.; Ozen, B. Authentication of a Turkish Traditional Aniseed Flavoured Distilled Spirit, Raki. Food Chem. 2013, 141, 1461–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Leeuw, A.; Valois, P.; Ajzen, I.; Schmidt, P. Using the theory of planned behavior to identify key beliefs underlying pro-environmental behavior in high-school students: Implications for educational interventions. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 42, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappalardo, G.; Lusk, J.L. The role of beliefs in purchasing process of functional foods. Food Qual. Prefer. 2016, 53, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinnici, G.; d’Amico, M.; Pecorino, B. A multivariate statistical analysis on the consumers of organic products. Br. Food J. 2002, 104, 187–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giampietri, E.; Verneau, F.; del Giudice, T.; Carfora, V.; Finco, A. A Theory of Planned behaviour perspective for investigating the role of trust in consumer purchasing decision related to short food supply chains. Food Qual. Prefer. 2018, 64, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skalkos, D.; Roumeliotis, N.; Kosma, I.S.; Yiakoumettis, C.; Karantonis, H.C. The Impact of COVID-19 on Consumers’ Motives in Purchasing and Consuming Quality Greek Wine. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Němcová, J.; Staňková, P. Factors influencing consumer behaviour of Generation Y on the Czech wine market. E+M Èkon. A Manag. 2019, 22, 145–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyedimany, A.; Koksal, M.H. Segmentation of Turkish Wine Consumers Based on Generational Cohorts: An Exploratory Study. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Groups | Sample Size (N) | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 682 | 68.6 |

| Male | 312 | 31.3 | |

| Age | 18–25 | 635 | 63.9 |

| 26–35 | 129 | 13 | |

| 36–45 | 130 | 13.1 | |

| 46–55 | 64 | 6.4 | |

| 55+ | 36 | 3.6 |

| Sample Size (N) | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Which of the alcohol beverages do you prefer? | ||

| Wine | 701 | 70.5 |

| Beer | 420 | 42.3 |

| Tsipouro 1 | 195 | 19.6 |

| Other | 188 | 18.9 |

| Ouzo 2 | 129 | 13 |

| Retsina 3 | 116 | 11.7 |

| Raki 4 | 67 | 6.7 |

| How often do you consume wine? | ||

| 1–2 times a week 1–2 times a month | 410 338 | 41.3 33.9 |

| Rarely | 225 | 22.6 |

| Daily | 20 | 2 |

| Which type of wine do you prefer? | ||

| Red | 613 | 61.7 |

| White | 340 | 34.2 |

| Rose/Blush | 200 | 20.1 |

| Which type of wine do you prefer? (Including sweetness) | ||

| Semi-sweet | 574 | 57.8 |

| Dry | 333 | 33.5 |

| Sparkling | 160 | 16.1 |

| Sweet | 117 | 11.8 |

| Semi-dry | 111 | 11.2 |

| Do you prefer to buy bottled wine or not? | ||

| Bottled | 659 | 66.3 |

| Bulk | 335 | 33.7 |

| Sample Size (N) | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| At what age did you start drinking wine? | ||

| Age | ||

| <18 | 550 | 55.3 |

| 18–25 | 390 | 39.2 |

| >26 | 54 | 5.5 |

| How much do you spend for a bottled wine? | ||

| <10 Euro | 492 | 49.5 |

| 11–20 Euro | 430 | 43.3 |

| 21–30 Euro | 52 | 5.2 |

| >30 Euro | 10 | 1.9 |

| Where do you usually buy your wine? | ||

| Supermarket | 594 | 59.8 |

| Liquor stores | 461 | 46.4 |

| Known-friend winemaker | 240 | 24.2 |

| Winery | 94 | 9.5 |

| Internet | 9 | 0.9 |

| Do you choose bottled wine as a gift? | ||

| Yes | 769 | 77.4 |

| No | 225 | 22.6 |

| Do you prefer Greek or foreign wines? | ||

| Greek | 942 | 94.8 |

| Foreign | 62 | 6.2 |

| Sample Size (N) | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Geographic region of the winery in Greece: | ||

| Macedonia (South Macedonia) | 17 | 23.94 |

| Peloponnese | 16 | 22.51 |

| Aegean islands | 11 | 15.49 |

| Central Greece | 8 | 11.26 |

| Crete | 7 | 9.85 |

| Thessaly | 6 | 8.45 |

| Ionian islands | 3 | 4.22 |

| Epirus | 2 | 2.81 |

| Thrace | 1 | 1.4 |

| How many employees do you employ? | ||

| 1–10 | 57 | 80.28 |

| 11–40 | 7 | 9.85 |

| 41–60 | 4 | 5.63 |

| 61–80 | 2 | 2.8 |

| 81–100 | 0 | 0 |

| >100 | 1 | 1.4 |

| What type of wine do you produce? | ||

| White | 70 | 98.59 |

| Dry | 70 | 98.59 |

| Red | 68 | 95.77 |

| Rosé/Blush | 66 | 92.95 |

| Semi-sweet | 28 | 39.43 |

| Sweet | 26 | 36.61 |

| Semi-dry | 20 | 28.16 |

| Sparkling | 7 | 9.85 |

| Where do you sell your products in Greece? | ||

| Liquor stores | 69 | 97.18 |

| Winery | 58 | 81.69 |

| Supermarkets | 40 | 56.33 |

| Internet | 20 | 28.16 |

| Cooperatives | 8 | 11.26 |

| Other (Horeca, delegations) | 1 | 1.4 |

| Is your winery open to visitors? | ||

| Yes | 58 | 81.69 |

| No | 13 | 18.3 |

| How do you package your wine? | ||

| In bottles | 41 | 57.74 |

| Both | 30 | 42.25 |

| Bulk | 0 | 0 |

| What is the annual production in bottles? | ||

| >100,000 | 33 | 46.47 |

| 10,000–50,000 | 23 | 32.39 |

| 50,000–100,000 | 10 | 14.08 |

| 5000–10,000 | 4 | 5.63 |

|

0–2000 2000–5000 |

1 0 |

1.4 0 |

| Scale | 1 = Not at all | 2 = Slightly | 3 = Moderately | 4 = Very | 5 = Extremely |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size (N) | 25 | 15 | 26 | 4 | 1 |

| Percentage (%) | 35.21% a | 21.12% b | 36.61% c | 5.63% d | 1.4% e |

| Sample Size (N) | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Do you export your wine? | ||

| Yes | 60 | 84.5 |

| No | 11 | 15.49 |

| What percentage of the annual production is exported? | ||

| 1–20% | 23 | 38.3 |

| 21–40% | 22 | 36.7 |

| 41–60% | 10 | 16.7 |

| 61–80% | 5 | 8.3 |

| 81–100% | 0 | 0 |

| How many years your company have been exporting? | ||

| 6–10 | 17 | 28.3 |

| 1–5 | 16 | 26.7 |

| >25 | 9 | 15 |

| 11–15 | 8 | 13.3 |

| 16–20 | 8 | 13.3 |

| 21–25 | 2 | 3.3 |

| In how many countries do you export? | ||

| 1–5 | 27 | 45 |

| 6–10 | 21 | 35 |

| 11–15 | 3 | 5 |

| 16–20 | 3 | 5 |

| 21–25 | 3 | 5 |

| >25 | 3 | 5 |

| In which countries your products are mainly exported to? * | ||

| Germany | 39 | 65 |

| United States of America | 38 | 63.3 |

| Canada | 22 | 36.66 |

| Italy | 2 | 16.66 |

| Austria | 5 | 15 |

| Cyprus | 6 | 10 |

| Australia | 6 | 10 |

| Netherlands | 4 | 6.66 |

| Sweden | 3 | 5 |

| Serbia | 2 | 3.33 |

| Russia | 2 | 3.33 |

| Switzerland | 1 | 1.66 |

| Luxembourg | 1 | 1.66 |

| Japan | 1 | 1.66 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sykalia, D.; Chrisostomidou, Y.; Karabagias, I.K. An Exploratory Research Regarding Greek Consumers’ Behavior on Wine and Wineries’ Character. Beverages 2023, 9, 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages9020043

Sykalia D, Chrisostomidou Y, Karabagias IK. An Exploratory Research Regarding Greek Consumers’ Behavior on Wine and Wineries’ Character. Beverages. 2023; 9(2):43. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages9020043

Chicago/Turabian StyleSykalia, Dionysia, Yvonni Chrisostomidou, and Ioannis K. Karabagias. 2023. "An Exploratory Research Regarding Greek Consumers’ Behavior on Wine and Wineries’ Character" Beverages 9, no. 2: 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages9020043

APA StyleSykalia, D., Chrisostomidou, Y., & Karabagias, I. K. (2023). An Exploratory Research Regarding Greek Consumers’ Behavior on Wine and Wineries’ Character. Beverages, 9(2), 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages9020043