1. Introduction

As any professional chef would know, our experience of food is not solely related to the sensations arising from the activation of a few chemical receptors on our tongue (see [

1,

2] for reviews). Just as it occurs for other aspects of our environment, beverage and food perception is determined by the complex interactions taking place among the different sensorial aspects of the stimuli and of their background, as well as by the way in which the brain integrates them into a whole experience.

A number of studies in the last two decades have started to investigate these important aspects [

2]. However, very few studies have specifically investigated taste–tactile interactions in beverage perception. Among these, Szczesniak [

3], somehow unsurprisingly, has shown that beverages containing lumps or hard particles make them unacceptable or inappropriate for participants. This effect is likely due to the fact that they provoke the fear of choking. Schifferstein [

4] used cups made of different materials (i.e., translucent plastic, opaque plastic, melamine, glass, ceramic) and asked participants to evaluate two different beverages: soda and hot tea. The participants also rated the empty cups with respect to a set of characteristics related to affective dimensions such as ‘pleasant–unpleasant’ or ‘good–bad’, as well as sensory perception across dimensions such as ‘heavy–light’ and ‘thick–thin’. The author found that the drinking experience followed the experience of the cups (e.g., the more pleasant the cup was perceived, the more pleasant the drink was perceived). Similarly, Krishna and Morrin [

5] investigated the effect of the firmness of a plastic cup on the taste perception of a mixed drink. The results showed that the firmer a cup was, the higher the participants evaluated the quality of the drink inside. Finally, Tu et al. [

6] investigated the effect of different packaging materials on taste perception of a traditional Chinese cold tea beverage. The results showed that people rated the sense of ice (a sub-dimension of the scale measuring sweetness) of the beverage as significantly higher when tasted by means of a glass cup with respect to paper or organic plastic cups.

It is worth noting here that touch plays a very important role for our emotional wellbeing [

7,

8,

9] and that tactile sensations can convey emotions [

10], just as the visual properties of stimuli do [

11]). Consequently, the emotional valence of the container textures [

12] during the manipulation might be transferred to the perception of the liquid contained in it, thus influencing its perceptual evaluation (e.g., more pleasant textures might lead to more pleasant evaluations of the water). Recently, Wang and Spence [

13] demonstrated that the same juice was rated as sweeter when presented together with visual and auditory positive-valenced stimuli (emotional faces and soundtracks harmonised with consonant music intervals) than when presented together with negatively-valenced stimuli. Importantly, as pointed out by the authors, to date the neural and cognitive correlates at the basis of these sensation transference effects (from the container to the content) are not completely clear.

The container texture effect on food might also be driven by people’s expectations based on their memory of previous experiences (exposure effects) with water [

14,

15]. In this case, the more the container deviates from a number of features perceived as ‘standard’ in water containers, the more the water was perceived as being less pleasant and lower in quality. Hence, one might expect that often-used containers, such as plastic glasses, lead to more positive water evaluations than novel—differently textured—containers [

16,

17,

18]. It is worth noting that in the studies reported so far, the container textures were all somehow congruent and compatible with participants’ previous drinking experiences. Consequently, it would seem difficult to test the hypothesis of an exposure effect [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. In fact, the extant literature lacks studies with novel or unusual container textures. Note, however, that companies are constantly searching for novel materials (possibly eco-sustainable) in order to enhance consumer experiences. Moreover, most previous studies used beverages characterised by specific odours, making it difficult to separate the effects determined by the multisensory interaction between taste and touch from those related to olfactory perception. In our paradigm, we tried to bypass these problems by using an odour-free liquid, namely water, and by using materials such as sandpaper and satin textures not commonly used for the production of water containers or packaging.

In our experiment, participants’ judgments on the liquid were expressed by means of four different scales: freshness, pleasantness, level of carbonation, and lightness. The same scales were previously used in other studies by our research group [

19,

20]. These scales were chosen among the descriptors of the categories used to classify the mouthfeel sensations of liquids [

21]. As previously mentioned, the choice of mineral water was due to the fact that it is odourless so that smell did not interfere with the evaluation of the features of the liquid (conversely to the beverages used in previous experiments on this matter; e.g., Tu et al. [

6]). By using this particular stimulus, we could directly analyse the effect of tactile qualities of containers on people’s taste perception of liquids, without the influence of other sensorial attributes of the stimuli. It is important to mention that in the present study, we wanted to exclude the so-called basic tastes (sweet, sour, bitter, salt) and odours perceived both retronasally and orthonasally from participants’ taste experience. The specific aim was to investigate tactile and trigeminal components of the flavour network in isolation [

22,

23,

24].

Given that water is often defined as tasteless by people (i.e., with the exception of highly trained ‘hydrosommeliers’), we asked our participants to assess the characteristics that are more closely linked to thirst or to the advertising campaign related to mineral water [

20,

25,

26] rather than the basic tastes (sweet, sour, salty, bitter, umami). If people’s perception of mineral water is affected by the emotional value of the stimuli, we would expect that certain characteristics of the water, such as its pleasantness, freshness, and lightness, would be enhanced by the tactile pleasantness of materials such as satin. By contrast, if people’s evaluations were mainly determined by exposure-related factors, we would expect that materials that deviate from the common drinking experience, such as satin and sandpaper, would result in negative effects: lower pleasantness, freshness and lightness.

3. Results

The participants’ mean ratings were submitted to a repeated measures ANOVA with the factors of texture of the plastic cup (i.e., sandpaper, satin, plastic), type of water (i.e., still, carbonated) and scales (i.e., freshness, pleasantness, level of carbonate, lightness). The results of the analysis revealed a significant main effect of the scale (F(3,141) = 13.96,

p < 0.001) and of texture (F(2,94) = 5.42,

p = 0.006), but not of water (F(1,47) = 3.68,

p = 0.061). The interaction between scale and texture (F(6,282) = 2.37,

p = 0.03), as well as the interaction between scale and water (F(3,141) = 118.43,

p < 0.001), resulted to be significant. The interaction between texture and water (F(2,94) = 0.06,

p = 0.94) and between scale, texture and water (F(6,282) = 1.14,

p = 0.34) were not significant. Newman–Keuls post hoc tests were performed on all the significant effects. The main effect of scale showed that on average, participants provided quantitatively lower evaluations (i.e., evaluations closer to the ‘not at all’ endpoint of the scale) for the intensity of carbonation scale than for freshness (

p < 0.001), pleasantness (

p < 0.001) and lightness (

p < 0.001) scales. A post hoc test on the significant effect of texture demonstrated that people on average provided quantitatively lower evaluations (i.e., evaluations closer to the ‘not at all’ endpoint of the scale) for sandpaper (

p = 0.01) and satin (

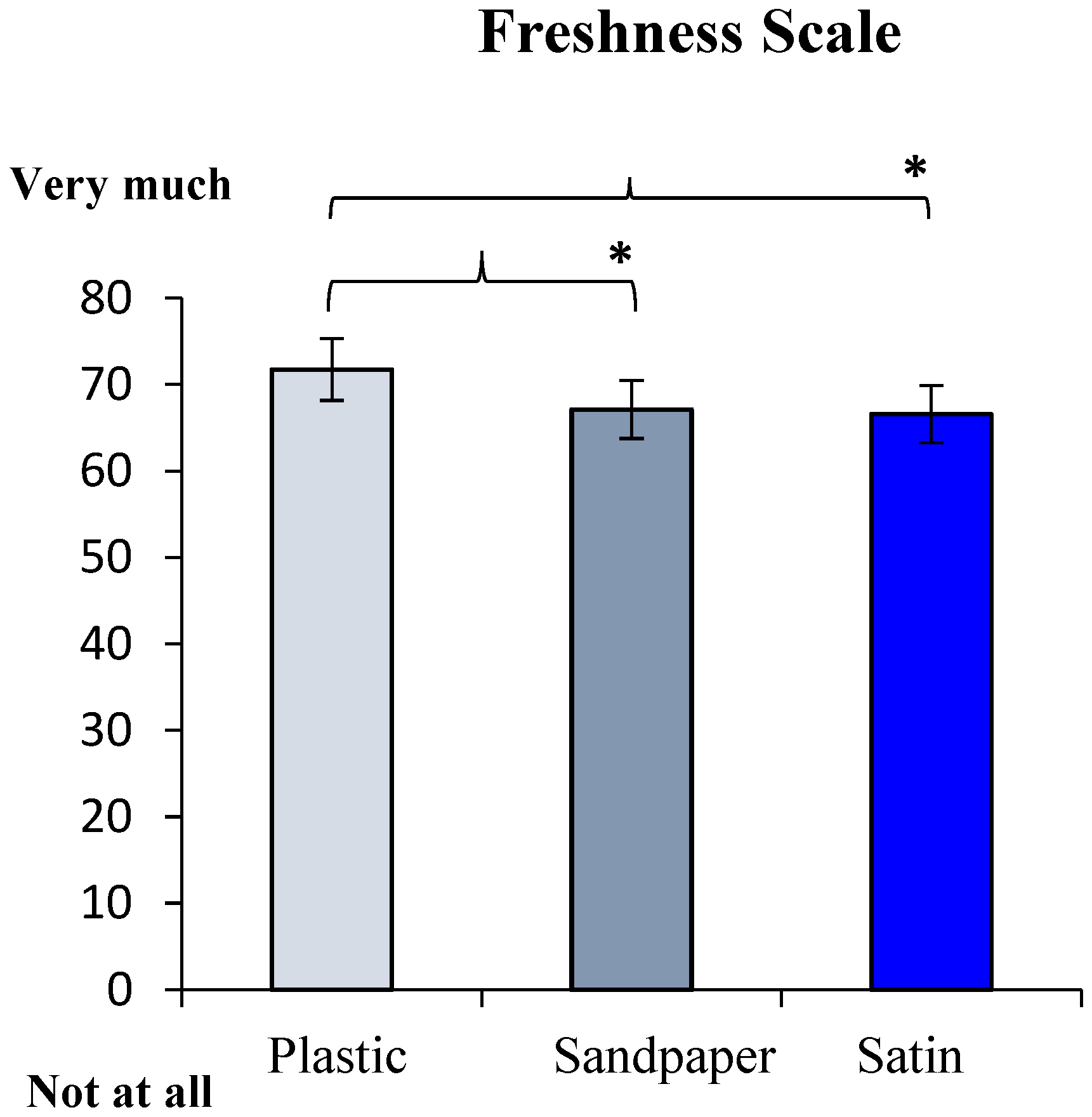

p = 0.01), as compared to the plastic texture. A post hoc test on the interaction between scale and texture revealed that participants perceived mineral water as fresher when served in a plastic cup as compared to a cup covered with sandpaper (

p = 0.049) or satin (

p = 0.028) (see

Figure 2).

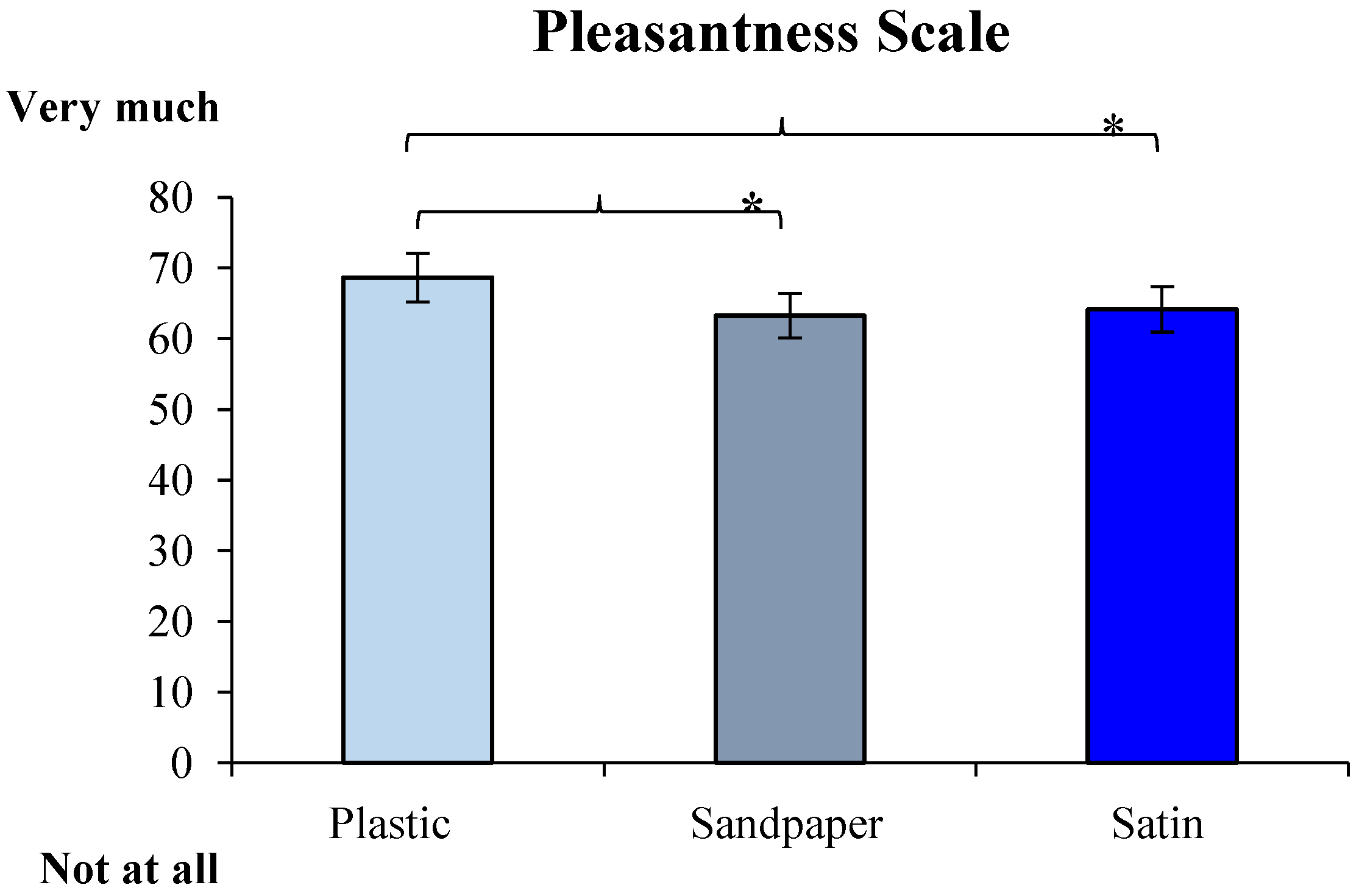

The post hoc test also revealed that water was perceived as more pleasant when served in a plastic cup as compared to water served in cups covered by sandpaper (

p = 0.01) or satin (

p = 0.04) (see

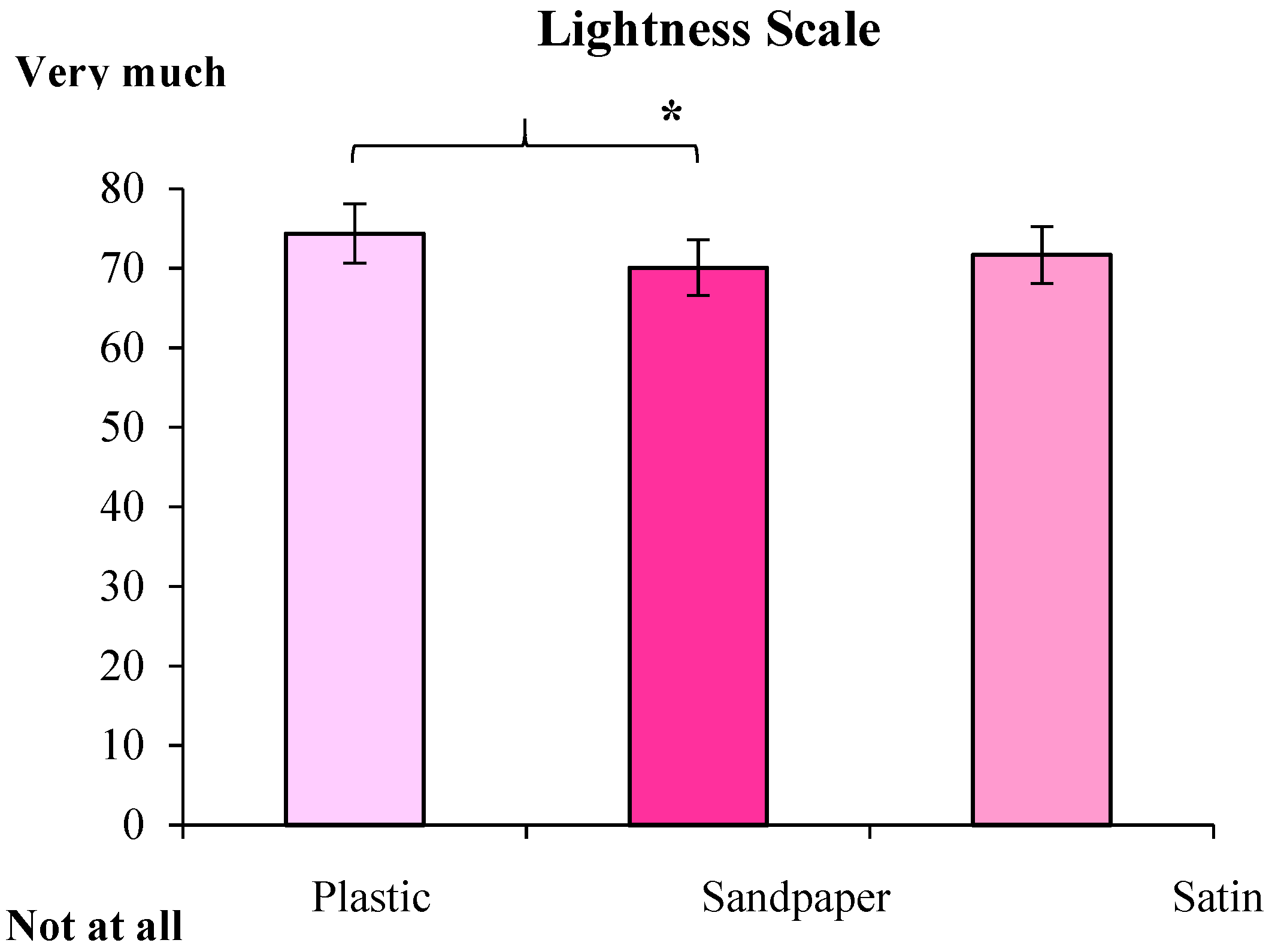

Figure 3). Finally, the results showed that the mineral water was perceived as lighter when served in a plastic cup than when served in a cup covered by sandpaper (

p = 0.054) (see

Figure 4). No significant differences were found on the scale of carbonation intensity. A post hoc test on the interaction between the factors of scale and water revealed that participants perceived still water as fresher (

p = 0.01), more pleasant (

p < 0.001) and lighter (

p < 0.001) than carbonated water. Not surprisingly, carbonated mineral water was perceived as more carbonated than still water (

p < 0.001).

A univariate ANOVA was performed on the participants’ pleasantness evaluations of the three textures. The results of the analysis revealed a significant main effect of texture (F(2,141) = 13.06, p < 0.001). A Newman–Keuls post hoc test showed that participants rated sandpaper as less pleasant than the satin (p < 0.001) and plastic (p < 0.001). Finally, people’s responses regarding their ability to recognise the textures and their preference for the mineral water were calculated: 47 individuals recognised the plastic (98%), 41 recognised the sandpaper (82%) and 2 recognised the satin (4%). As far as the evaluations of the water preferences are concerned, 36 participants, in general, preferred to drink still water (75%), 10 carbonated water (21%), and 2 slightly carbonated water (4%).

A linear regression analysis was performed to evaluate the possible presence of a relationship between the perception of mineral water and the pleasantness of the textures on each of the four scales. The four dimensions investigated freshness (r = 0.11, p = 0.93), pleasantness (r = 0.35, p = 0.77), carbonation intensity (r = 0.93, p = 0.23) and lightness (r = 0.55, p = 0.63) of the water and did not show any significant correlation with the perceived pleasantness of the textures.

4. General Discussion and Conclusions

The results of the present study revealed that the perception of certain attributes/qualities of mineral water was affected by the different textures used to cover the cups in which the liquid was served. In particular, participants perceived both still and carbonated mineral water as fresher and more pleasant when the liquid was tasted in a plastic cup as compared to conditions where the cups were covered by sandpaper or satin. On the dimensions of lightness, we found that people perceived mineral water as lighter when the liquid was tasted in plastic cups as compared to conditions where the cups were covered by sandpaper. The dimension of carbonation intensity was not modulated by the different container textures.

As far as the result on the dimension of freshness is concerned, it is important to highlight that in Italian, this word is usually referred to the thirst-quenching characteristics of a drink more than its temperature. As a matter of fact, the water was served at constant room temperature (19–22 °C) and it is unlikely that the participants could perceive it as really ‘fresh’. Therefore, it is unlikely that by holding a plastic cup or holding a cup covered by satin or sandpaper, they could have perceived a different temperature of the liquid inside. Therefore, it is difficult to argue that participants’ water taste perception in our experiment was only affected by the different surface temperature of the three different cups adopted. However, we believe that temperature variables of the container might be able to contribute to people’s perception of the content. This aspect should be further investigated in the future.

Similar considerations also apply to the lightness dimension. That is, although the cups were covered by different materials, their physical weight was unlikely perceived as different by the participants (variations were in terms of fractions of milligrams). Moreover, if the effect found was due to weight differences between the glasses, probably such difference should have also involved the cup covered with satin, where instead no effect was reported.

It might be speculated that the degree of the appropriateness of the container to the whole drinking experience could explain the effect reported in the present study. In fact, it is possible that the participants, as a function of their previous experiences, considered the plastic cup—i.e., that one covered by the same material used to make the cup—as the more appropriate container from which to drink mineral water. In fact, this condition might be considered more similar to the typical beverage drinking experience stored in memory within a given culture. This experience-based interpretation agrees with Woods et al.’s [

18] model, suggesting that flavour sensations fluctuate in order to harmonise with the expectations generated from actual and past food/beverage experiences. It might also be possible that participants transferred to the water some of the characteristics of the texture (such as the presence of rough particles of sandpaper and of fabrics), thus diminishing the level of acceptance of the water [

3,

27].

It is important to mention here that the effects found could also be related to emotional responses to the stimuli. Specifically, with reference to the affective ventriloquist effect [

28]), the emotional response elicited by a tactile aspect of the container might affect the overall evaluation of the drinking experience. That is, containers covered with sandpaper and satin may have caused here an unpleasant negative feeling regarding the experience of drinking mineral water that is usually served in glass or plastic containers. Such a hypothesis could be strengthened by the fact that also the pleasantness dimension was decreased by the presence of unusual textures such as satin and sandpaper.

The perceptions of males and females were not evaluated in the current study.

In conclusion, the results of the present study show that the perception of mineral water can be modulated by the texture of the materials used to cover the cups in which the liquid is served. In particular, unusual container textures—at least those adopted in the present study—can lower people’s perception of certain mineral water characteristics. Further investigations should be directed to assess whether the effects found in the present study are consistent over time or fluctuate depending on people’s repeated exposure to specific textures and materials. Moreover, future research will also need to assess how different types of liquids interact with the same characteristics of the textures used to cover the containers. For example, one might study the effect of sandpaper-coated cups on the taste perception of grainy beverages such as pear juice. From an applied point of view, the results of the present study could help researchers in the field of environmentally-friendly materials. That is, it will be really important in the future to determine the perceptual effects of new and more eco-sustainable materials on people’s expectations, consumption and choice of food and beverage. Finally, our results might also suggest that unusual container textures could perhaps be used to contribute to reducing the consumption of beverages potentially harmful to health, for example, alcoholic and/or drinks with a high sugar content [

2].