Phenolic Compounds and Antioxidant Activity in Grape Juices: A Chemical and Sensory View

Abstract

:1. General Introduction

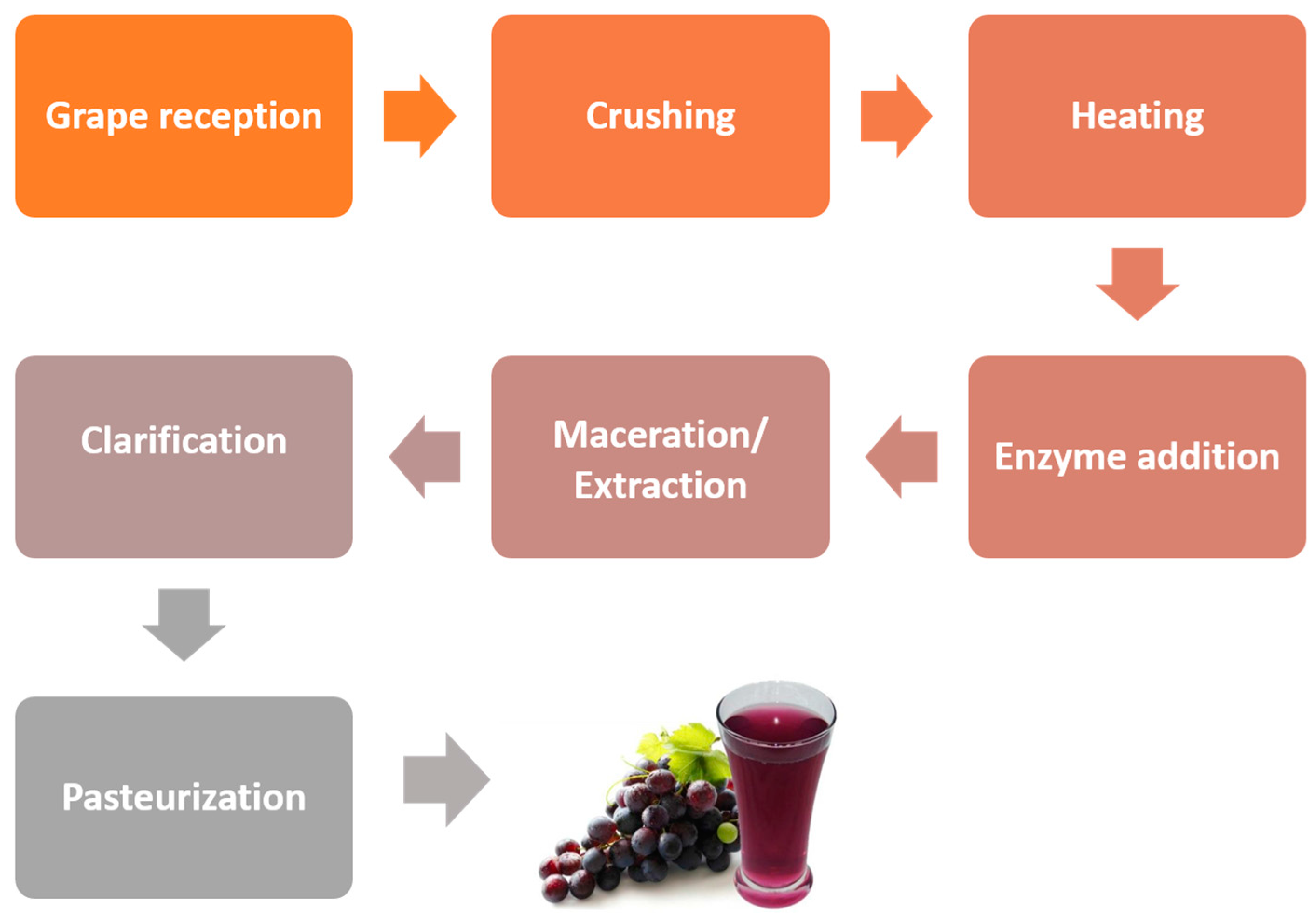

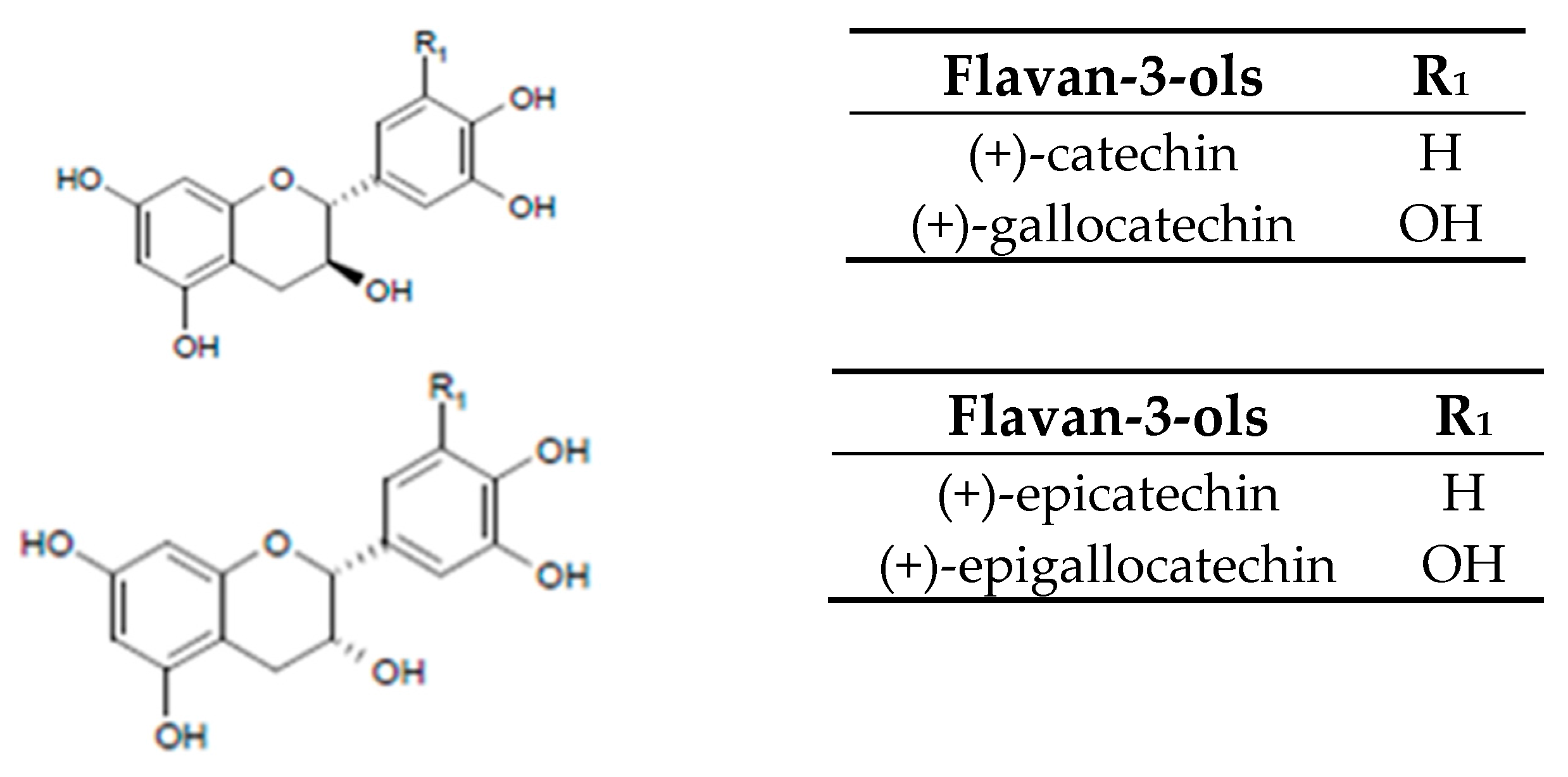

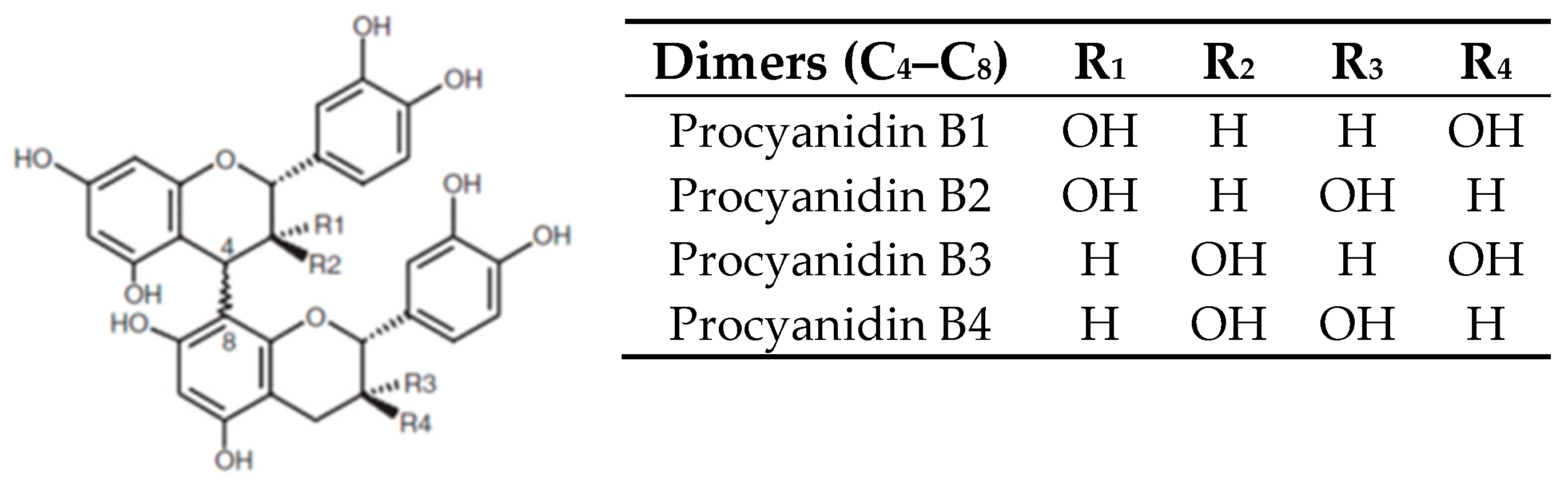

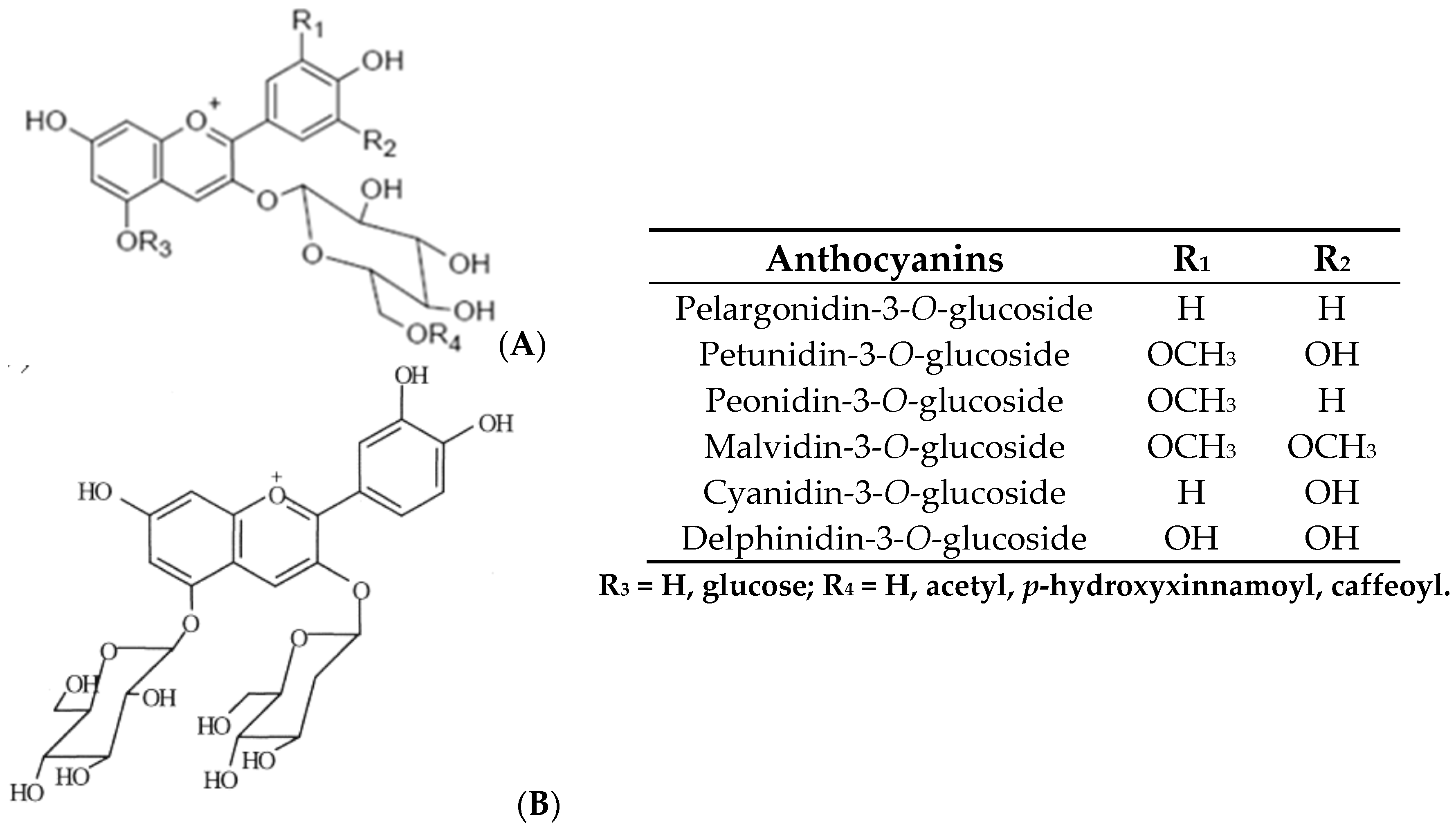

2. Grape Juice Production and Phenolic Composition

3. Biological Activity of Phenolic Compounds Present in Grape Juices

4. Sensory Characteristics of Grape Juices

5. Conclusions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rizzon, L.A.; Meneguzzo, J. Suco de Uva, 1st ed.; Embrapa Technological Information: Brasília, Brazil, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, K.; Maltese, F.; Choi, Y.; Verpoorte, R. Metabolic constituents of grapevine and grape-derived products. Phytochem. Rev. 2010, 9, 357–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizzon, L.A.; Manfroi, V.; Meneguzo, J. Elaboração de Suco de uva na Propriedade Vitícola; Embrapa-CNPUV: Bento Gonçalves, Brazil, 1998; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Camargo, U.A.; Maia, J.D.G.; Ritschel, P.S. Novas Cultivares Brasileiras de Uva; Embrapa Uva e Vinho: Bento Gonçalves, Brazil, 2010; 64p. [Google Scholar]

- Dutra, M.C.P.; Lima, M.S.; Barros, A.P.A.; Mascarenhas, R.J.; Lafisca, A. Influência da variedade de uvas nas características analíticas e aceitação sensorial do suco artesanal. Rev. Bras. Prod. Agroind. 2014, 16, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soundararajan, R.; Wishart, A.D.; Rupasinghe, H.P.V.; Arcellana-Panlilio, M.; Nelson, C.M.; Mayne, M.; Robertson, G.S. Quercetin-3-glucoside protects neuroblastoma (SH-SY5Y) cells in vitro against oxidative damage by inducing SREBP-2 mediated cholesterol biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 2231–2245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gollücke, A.P.B.; Catharino, R.R.; Souza, J.C.; Eberlin, M.N.; Tavares, D.Q. Evolution of major phenolic components and radical scavenging activity of grape juices through concentration process and storage. Food Chem. 2009, 112, 868–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraga, C.G.; Galleano, M.; Verstraeten, S.V.; Oteiza, P.I. Basic biochemical mechanisms behind the health benefits of polyphenols. Mol. Asp. Med. 2010, 31, 435–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamagata, K.; Tagami, M.; Yamori, Y. Dietary polyphenols regulate endothelial function and prevent cardiovascular disease. Nutrition 2015, 31, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mintel. Functional Beverages-US August; Market Research Report; Mintel International Group Ltd.: Chicago, IL, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- OIV—Organisation Internationale de la Vigne et du Vin. Vine and Wine Outlook; OIV: Paris, France, 2012; ISBN 979-10-91799-56-0. [Google Scholar]

- Soyer, Y.; Koca, N.; Karadeniz, F. Organic acid profile of Turkish white grapes and grape juices. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2003, 16, 629–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, J.R. Factors influencing grape juice quality. Hort Technol. 1998, 8, 471–478. [Google Scholar]

- Iyer, M.M.; Sacks, G.L.; Padilla-Zakour, O.I. Impact of harvesting and processing conditions on green leaf volatile development and phenolics in concord grape juice. J. Food Sci. 2010, 75, 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizzon, L.A.; Miele, A. Características analíticas e discriminação de suco, néctar e bebida de uva comerciais brasileiros. Ciênc Tecnol Aliment. 2012, 32, 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stalmach, A.; Edwards, C.A.; Wightman, J.D.; Crozier, A. Identification of (Poly)phenolic Compounds in Concord Grape Juice and Their Metabolites in Human Plasma and Urine after Juice Consumption. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 9512–9522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro, T.P.; Lima, M.A.C.; Alves, R.E. Maturação e qualidade de uvas para suco em condições tropicais, nos primeiros ciclos de produção. Pesq. Agrop. Bras. 2012, 47, 1057–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camargo, U.A. ‘Isabel Precoce’: Alternativa Para a Vitivinicultura Brasileira. In Comunicado Técnico N° 54; Embrapa Uva e Vinho: Bento Gonçalves, Brazil, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Camargo, U.A.; Maia, J.D.G. “BRS Cora” nova cultivar de uva para suco, adaptada a climas tropicais. In Comunicado Técnico N° 53; Embrapa Uva e Vinho: Bento Gonçalves, Brazil, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Camargo, U.A.; Maia, J.D.G.; Nachtigal, J.C. “BRS Violeta” nova cultivar de uva para suco e vinho de mesa. In Comunicado Técnico N° 63; Embrapa Uva e Vinho: Bento Gonçalves, Brazil, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, J.R.; Striegler, K.R. Processing Fruits: Science and Technology, 2nd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Lima, M.S.; Dutra, M.C.P.; Toaldo, I.M.; Corrêa, L.C.; Pereira, G.L.; Oliveira, D.; Bordignon-Luiz, M.T.; Ninowd, J.L. Phenolic compounds, organic acids and antioxidant activity of grape juices produced in industrial scale by different processes of maceration. Food Chem. 2015, 188, 384–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monrad, J.K.; Suárez, M.; Motilva, M.J.; King, J.W.; Srinivas, K.; Howard, L.R. Extraction of anthocyanins and flavan-3-ols from red grape pomace continuously by coupling hot water extraction with a modified expeller. Food Res. Int. 2014, 65, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelebek, H.; Canbas, A.; Selli, S. Effects of different maceration times and pectolytic enzyme addition on the anthocyanin composition of Vitis vinifera cv. Kalecik karasi wines. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2009, 33, 296–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastrana-Bonilla, E.; Akoh, C.C.; Sellappan, S.; Krewer, G. Phenolic content and antioxidant capacity of Muscadine grapes. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 5497–5503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruno, G.; Sparapano, L. Effects of three esca-associated fungi on Vitis vinifera L. Changes in the chemical and biological profile of xylem sap from diseased cv. Sangiovese vines. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2007, 71, 210–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rombaldi, C.V.; Bergamasqui, M.; Lucchetta, L.; Zanuzo, M.; Silva, J.A. Vineyard yield and grape quality in two different cultivation systems. Rev. Bras. Frutic. 2004, 26, 89–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankel, E.N.; Bosanek, C.A.; Meyer, A.S.; Silliman, K.; Kirk, L.L. Commercial grape Juices inhibit the in vitro oxidation of human low density lipoproteins. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1998, 46, 834–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido, J.; Borges, F. Wine and grape polyphenols—A chemical perspective. Food Res. Int. 2013, 54, 1844–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahidi, F.; Naczk, M. Phenolic compounds in fruits and vegetables. In Phenolics in Food and Nutraceuticals; CRC Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004; pp. 144–151. [Google Scholar]

- Corrales, M.; García, A.F.; Butz, P.; Tauscher, B. Extraction of anthocyanins from grape skins assisted by high hydrostatic pressure. J. Food Eng. 2009, 90, 415–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Darra, N.E.; Grimi, N.; Maroun, R.G.; Louka, N.; Vorobiev, E. Pulsed electric field, ultrasound, and thermal pretreatments for better phenolic extraction during red fermentation. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2013, 236, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Darra, N.E.; Grimi, N.; Vorobiev, E.; Louka, N.; Maroun, R. Extraction of polyphenols from red grape pomace assisted by pulsed ohmic heating. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2013, 6, 1281–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacchi, K.L.; Bisson, L.F.; Adams, D.O. A review of the effect of winemaking techniques on phenolic extraction in red wines. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2005, 56, 197–206. [Google Scholar]

- Celotti, E.; Rebecca, S. Recenti esperienze di termomacerazione delle uve rosse. Industrie delle Bevande 1998, 155, 245–255. [Google Scholar]

- Prieur, C.; Rigaud, J.; Cheynier, V.; Moutounet, M. Oligomeric and polymeric procyanidins from grape seeds. Phytochemistry 1994, 3, 781–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souquet, J.M.; Cheynier, V.; Brossaud, F.; Moutounet, M. Polymeric proanthocyanidins from grape skins. Phytochemistry 1996, 43, 509–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Mu, L.; Yan, G.L.; Liang, N.N.; Pan, Q.H.; Wang, J.; Reeves, M.J.; Duan, C.Q. Biosynthesis of Anthocyanins and Their Regulation in Colored Grapes. Molecules 2010, 15, 9057–9091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuleki, T.; Ricardo-Da-Silva, J.M. Effects of cultivar and processing method on the contents of catechins and procyanidins in grape juice. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 640–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shrikhande, A.J. Wine by-products with health benefits. Food Res. Int. 2000, 33, 469–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wroblewski, K.; Muhandiram, R.; Chakrabartty, A.; Bennick, A. The molecular interaction of human salivary histatins with polyphenolic compounds. Eur. J. Biochem. 2001, 268, 4384–4397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auger, C.; Teissedre, P.L.; Gerain, P.; Lequeux, N.; Bornet, A.; Serisier, S.; Besançon, P.; Caporiccio, B.; Cristol, J.P.; Rouanet, J.M. Dietary wine phenolics catechin, quercetin, and resveratrol efficiently protect hypercholesterolemic hamsters against aortic fatty streak accumulation. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 2015–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jordão, A.M.; Ricardo-da-Silva, J.M.; Laureano, O. Evolution of catechins and oligomeric procyanidins during grape maturation of Castelão Francês and Touriga Francesa. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2001, 52, 230–234. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, B.S.; Ricardo-da-Silva, J.M.; Spranger, M.I. Quantification of catechins and proanthocyanidins in several Portuguese grapevine varieties and red wines. Ciência Téc Vitiv 2001, 16, 23–34. [Google Scholar]

- Ribéreau-Gayon, P.; Dubourdieu, D.; Donèche, B.; Lonvaud, A. Trattato di Enologia: Microbiologia del vino e Vinificazioni, 2nd ed.; Edagricole: Bologna, Italy, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Rubilar, M.; Pinelo, M.; Shene, C.; Sineiro, J.; Nunez, M.J. Separation and HPLC-MS identification of phenolic antioxidants from agricultural residues: Almond hulls and grape pomace. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 10101–10109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, R.S. Wine Science Principle and Applications, 3rd ed.; Academic Press: Burlington, VT, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Dopico-Garcia, M.S.; Fique, A.; Guerra, L.; Afonso, J.M.; Pereira, O.; Valentao, P.; Andrade, P.B.; Seabra, R.M. Principal components of phenolics to characterize red Vinho Verde grapes: Anthocyanins or non-coloured compounds? Talanta 2008, 75, 1190–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vilela, A.; Cosme, F. Drink Red: Phenolic Composition of Red Fruit Juices and Their Sensorial Acceptance. Beverages 2016, 2, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.M.; He, J.J.; Bi, H.Q.; Cui, X.Y.; Duan, C.Q. Phenolic Compound Profiles in Berry Skins from Nine Red Wine Grape Cultivars in Northwest China. Molecules 2009, 14, 4922–4935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabrera, S.G.; Jang, J.I.H.; Kim, S.T.; Lee, Y.R.; Lee, H.J.; Chung, H.S.; Moon, K.D. Effects of processing time and temperature on the quality components of Campbell grape juice. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2009, 33, 347–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagchi, D.; Bagchi, M.; Stohs, S.J.; Das, D.K.; Ray, C.A.; Kuszynski, S.S.; Joshi, H.G. Free radicals and grape seed proanthocyanidin extract: Importance in human health and disease prevention. Toxicology 2000, 148, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantos, E.; Espin, J.C.; Tomas-Barberan, F.A. Varietal differences among the polyphenol profiles of seven table grape cultivars studied by LC-DAD-MS-MS. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 5691–5696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makris, D.P.; Kallithrakab, S.; Kefalasa, K. Flavonols in grapes, grape products and wines: Burden, profile and influential parameters. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2006, 19, 396–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pace-Asciak, C.R.; Rounova, O.; Hahn, S.E.; Diamandis, E.P.; Goldberg, D.M. Wines and grape juices as modulators of platelet aggregation in healthy human subject. Clin. Chim. Acta 1996, 246, 163–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daglia, M. Polyphenols as antimicrobial agents. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2012, 23, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sautter, C.K.; Denardin, S.; Alves, A.O.; Mallmann, C.A.; Penna, N.G.; Hecktheuer, L.H. Determinação de resveratrol em sucos de uva no Brasil. Ciênc. Tecnol. Aliment. 2005, 25, 437–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capanoglu, E.; Vos, R.C.H.; Hall, R.D.; Boyacioglu, D.; Beekwilder, J. Changes in polyphenol content during production of grape juice concentrate. Food Chem. 2013, 139, 521–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dani, C.; Oliboni, L.S.; Vanderlinde, R.; Bonatto, D.; Salvador, M.; Henriques, J.A.P. Phenolic content and antioxidant activities of white and purple juices manufactured with organically- or conventionally-produced grapes. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2007, 45, 2574–2580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lima, M.S.; Silani, I.S.V.; Toaldo, I.M.; Corrêa, L.C.; Biasoto, A.C.T.; Pereira, G.E.; Bordignon-Luiz, M.T.; Ninow, J.L. Phenolic compounds, organic acids and antioxidant activity of grape juices produced from new Brazilian varieties planted in the Northeast Region of Brazil. Food Chem. 2014, 161, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toaldo, I.M.; Cruz, F.A.; Alves, T.L.; Gois, J.S.; Borges, D.L.G.; Cunha, H.P.; Silva, E.L.; Bordignon-Luiz, M.T. Bioactive potential of Vitis labrusca L. grape juices from the Southern Region of Brazil: Phenolic and elemental composition and effect on lipid peroxidation in healthy subjects. Food Chem. 2015, 173, 527–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balasundram, N.; Sundram, K.; Samman, S. Phenolic compounds in plants and agri-industrial by-products: Antioxidant activity, occurrence, and potential uses. Food Chem. 2006, 99, 191–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice-Evans, C.A.; Miller, N.J.; Paganga, G. Structure-antioxidant activity relationships of flavonoids and phenolic acids. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1996, 20, 933–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, M.; Sanchez-Moreno, C.; Pascual-Teresa, S. Flavonoid-flavonoid interaction and its effect on their antioxidant activity. Food Chem. 2010, 121, 691–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiev, V.; Ananga, A.; Tsolova, V. Recent Advances and Uses of Grape Flavonoids as Nutraceuticals. Nutrients 2014, 6, 391–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wada, M.; Kido, H.; Ohyama, K.; Ichibangas, T.; Kishikaw, N.; Ohba, Y.; Nakashima, M.N.; Kurod, N.; Nakashima, K. Chemiluminescent screening of quenching effects of natural colorants against reactive oxygen species: Evaluation of grape seed, monascus, gardenia and red radish extracts as multi-functional food additives. Food Chem. 2007, 101, 980–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinova, E.M.; Yanishlieva, N.V. Antioxidant activity and mechanism of action of some phenolic acids at ambient and high temperatures. Food Chem. 2003, 81, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coimbra, S.R.; Lage, S.H.; Brandizzi, L.; Yoshida, V.; da Luz, P.L. The action of red wine and purple grape juice on vascular reactivity is independent of plasma lipids in hypercholesterolemic patients. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2005, 38, 1339–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dohadwala, M.M.; Vita, J.A. Grapes and Cardiovascular Disease. J. Nutr. 2009, 139, 1788–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aviram, M.; Fuhrman, B. Wine flavonoids protect against LDL oxidation and atherosclerosis. Alcohol and Wine in Health and Disease. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2002, 957, 146–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mudnic, I.; Modun, D.; Rastija, V.; Vukovic, J.; Brizic, I.; Katalinic, V.; Kozina, B.; Medic-Saric, M.; Boban, M. Antioxidative and vasodilatory effects of phenolic acids in wine. Food Chem. 2010, 119, 1205–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, M.; Cai, L.; Udeani, G.O.; Slowing, K.V.; Thomas, C.F.; Beecher, C.W.W.; Fong, H.H.S.; Farnsworth, N.R.; Kinghorn, A.D.; Mehta, R.G.; et al. Cancer Chemopreventive Activity of Resveratrol, a Natural Product Derived from Grapes. Science 1997, 275, 218–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zunino, S. Type 2 Diabetes and Glycemic Response to Grapes or Grape Products. J. Nutr. 2009, 139, 1794–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joseph, J.A.; Shukitt-Hale, B.; Willis, L.M. Grape Juice, Berries, and Walnuts Affect Brain Aging and Behavior. J. Nutr. 2009, 139, 1813–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Modun, D.; Music, I.; Vukovic, J.; Brizic, I.; Katalinic, V.; Obad, A.; Palada, I.; Dujic, Z.; Boban, M. The increase in human plasma antioxidant capacity after red wine consumption is due to both plasma urate and wine polyphenols. Atherosclerosis 2008, 197, 250–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ursini, F.; Sevanian, A. Wine Polyphenols and Optimal Nutrition. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2002, 957, 200–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dávalos, A.; Fernández-Hernando, C.; Cerrato, F.; Martínez-Botas, J.; Gómez-Coronado, D.; Gómez-Cordovés, C.; Lasunción, M.A. Red Grape Juice Polyphenols Alter Cholesterol Homeostasis and Increase LDL-Receptor Activity in Human Cells In Vitro. J. Nutr. 2006, 136, 1766–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castilla, P.; Echarri, R.; Davalos, A.; Cerrato, F.; Ortega, H.; Teruel, J.L.; Lucas, M.F.; Gomez-Coronado, D.; Ortuno, J.; Lasuncion, M.A. Concentrated red grape juice exerts antioxidant, hypolipidemic, and anti-inflammatory effects in both hemodialysis patients and healthy subjects. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2006, 84, 252–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernandez-Jimenez, A.; Gomez-Plaza, E.; Martinez-Cutillas, A.; Kennedy, J.A. Grape skin and seed proanthocyanidins from Monastrell x Syrah grapes. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 10798–10803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novaka, I.; Janeiroa, P.; Serugab, M.; Oliveira-Brett, A.M. Ultrasound extracted flavonoids from four varieties of Portuguese red grape skins determined by reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography with electrochemical detection. Anal. Chim. Acta 2008, 630, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spáčil, Z.; Nováková, L.; Solich, P.; Spacil, Z.; Novakova, L.; Solich, P. Analysis of phenolic compounds by high performance liquid chromatography and ultra performance liquid chromatography. Talanta 2008, 76, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Natividade, M.M.P.; Corrêa, L.C.; Souza, S.V.C.; Pereira, G.E.; Lima, L.C.O. Simultaneous analysis of 25 phenolic compounds in grape juice for HPLC: Method validation and characterization of São Francisco Valley samples. Microchem. J. 2013, 110, 665–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, E.-Q.; Deng, G.-F.; Guo, Y.-J.; Li, H.-B. Biological Activities of Polyphenols from Grapes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2010, 11, 622–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soleas, G.J.; Diamandis, E.P.; Goldberg, D.M. Resveratrol: A molecule whose time has come? And gone? Clin. Biochem. 1997, 30, 91–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbonaro, M.; Mattera, M.; Nicoli, S.; Bergamo, P.; Capelloni, M. Modulation of antioxidant compounds in organic vs. conventional fruit (peach, Prunus persica L.; and pear, Pyrus commumis L.). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 5458–5462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grinder-Pederson, L.; Rasmussen, S.E.; Bugel, S.; Jørgensen, L.V.; Dragsted, L.O.; Gundersen, V.; Sandström, B. Effect of diets based on foods from conventional versus organic production on intake and excretion o flavonoids and markers of antioxidative defense in humans. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 5671–5676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leblanc, M.R.; Johnson, C.E.; Wilson, P.W. Influence of pressing method on juice stilbene content in Muscadine and Bunch grapes. J. Food Sci. 2008, 73, 58–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Treptow, T.C.; Franco, F.W.; Mascarin, L.G.; Hecktheuer, L.H.R.; Sautter, C.K. Physicochemical Composition and Sensory Analysis of Whole Juice Extracted from Grapes Irradiated with Ultraviolet C. Rev. Bras. Frutic. 2017, 39, e579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattivi, F.; Guzzon, R.; Vrhovsek, U.; Stefanini, M.; Velasco, R. Metabolite profiling of grape: Flavonols and anthocyanins. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 7692–7702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burin, V.M.; Falcão, L.D.; Gonzaga, L.V.; Fett, R.; Rosier, J.P.; Bordignon-Luiz, M.-T. Colour, phenolic content and antioxidant activity of grape juice. Food Sci. Technol. 2010, 30, 1027–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurak, P.D.; Cabral, L.M.C.; Rocha-Leão, M.H.M.; Matta, V.M.; Freitas, S.P. Quality evaluation of grape juice concentrated by reverse osmosis. J. Food Eng. 2010, 96, 421–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downey, M.O.; Krstic, M.K.; Dokoozlian, N.K. Cultural practice and environment impacts on the flavonoid composition of grapes and wine—A review of recent research. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2006, 57, 257–268. [Google Scholar]

- Bautista-Ortín, A.B.; Fernández-Fernández, J.I.; López-Roca, J.M.; Gómez-Plaza, M. The effects of enological practices in anthocyanins, phenolic compounds and wine colour and their dependence on grape characteristics. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2007, 546–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meullenet, J.-F.; Lovely, C.; Threlfall, R.; Morris, J.R.; Striegler, R.K. An ideal point density plot method for determining an optimal sensory profile for Muscadine grape juice. Food Qual. Preference 2008, 19, 210–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huckleberry, J.M.; Morris, J.R.; James, C.; Marx, D.; Rathburn, I.M. Evaluation of Wine Grapes for Suitability in Juice Production. J. Food Qual. 1990, 13, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girard, B.; Mazza, G. Produtos Funcionales derivados de lãs uvas y de los cítricos. Cap 5. In Alimentos Funcionales: Aspectos Bioquímicos e de Procesado; Mazza, G., Acribia, S.A., Eds.; Acribia: Zaragoza, Spain, 1998; pp. 141–182. [Google Scholar]

- Öncül, N.; Karabiyikli, S. Factors affecting the quality attributes of unripe grape functional food products. J. Food Biochem. 2015, 39, 689–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simone, G.V.; Montevecchi, G.; Masino, F.; Matrella, V.; Imazio, S.A.; Antonelli, A.; Bignami, C. Ampelographic and chemical characterization of Reggio Emilia and Modena (northern Italy) grapes for two traditional seasonings: ‘Saba’ and ‘agresto’. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2013, 93, 3502–3511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alipour, M.; Davoudi, P.; Davoudi, Z. Effects of unripe grape juice (verjuice) on plasma lipid profile, blood pressure, malondialdehyde and total antioxidant capacity in normal, hyperlipidemic and hyperlipidemic with hypertensive human volunteers. J. Med. Plants Res. 2012, 6, 5677–5683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setorki, M.; Asgary, S.; Eidi, A.; Rohani, A.H. Effects of acute verjuice consumption with a high-cholesterol diet on some biochemical risk factors of atherosclerosis in rabbits. Med. Sci. Monit. 2010, 16, 124–130. [Google Scholar]

- Öncül, N.; Karabiyikli, S. Survival of foodborne pathogens in unripe grape products. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 74, 168–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karabiyikli, Ş.; Öncül, N. Inhibitory effect of unripe grape products on foodborne pathogens. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2016, 40, 1459–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, S.; Vitorino, R.; Osório, H.; Fernandes, A.; Venâncio, A.; Mateus, N.; Freitas, V. Reactivity of human salivary proteins families toward food polyphenols. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 5535–5547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matos, A.D.; Curioni, A.; Bakalinsky, A.T.; Marangon, M.; Pasini, G.; Vincenzi, S. Chemical and sensory analysis of verjuice: An acidic food ingredient obtained from unripe grape berries. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2017, 44, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taste of Beirut. Sour Grapes to Make Verjuice or Husrum. Available online: http://www.tasteofbeirut.com/sour-grapes-to-make-verjuice-or-husrum/ (accessed on 12 December 2017).

| Phenolic Compounds | Temperature/Enzyme | Grape Variety | Grape Production | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50 °C/3.0 g | 60 °C/3.0 g | Isabel Precoce | BRS Cora | BRS Violeta | Organic | Conventional | |

| (+)-Catechin | 9.9 ± 0.5 | 11.2 ± 3.4 | 4.7 ± 0.1 | 12.4 ± 0.3 | 19.8 ± 0.4 | 500.52 ± 12.33 | 79.89 ± 30.19 |

| (−)-Epicatechin | 0.8 ± 0.7 | 1.7 ± 0.3 | 1.0 ± 1.0 | 1.4 ± 0.5 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 53.48 ± 19.78 | 14.40 ± 0.77 |

| (−)-Epicatechin gallate | 2.2 ± 1.2 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 1.2 ± 0.0 | 1.9 ± 0.2 | - | - |

| (−)-Epigallocatechin gallate | 2.1 ± 0.5 | 1.8 ± 0.3 | - | - | . | - | - |

| (−)-Epigallocatechin | - | - | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 4.7 ± 0.4 | 6.2 ± 0.1 | - | - |

| Procyanidin A2 | 2.6 ± 0.2 | 3.0 ± 0.2 | 2.8 ± 0.2 | 2.9 ± 0.2 | 3.6 ± 0.1 | - | - |

| Procyanidin B1 | 34.4 ± 2.4 | 36.8 ± 0.8 | 47.1 ± 0.1 | 37.2 ± 0.6 | 44.2 ± 0.3 | - | - |

| Procyanidin B2 | 13.1 ± 3.1 | 16.1 ± 2.5 | 14.3 ± 0.1 | 16.3 ± 0.7 | 17.5 ± 0.5 | - | - |

| trans-Resveratrol | 0.90 ± 0.3 | 0.90 ± 0.4 | - | - | - | 3.73 ± 0.19 | 2.24 ± 0.07 |

| Malvidin 3,5-diglucoside | 5.2 ± 1.0 | 6.4 ± 0.1 | 1.8 ± 0.0 | 0.7 ± 0.0 | 11.7 ± 0.0 | 721.26 ± 20.99 | 189.43 ± 1.29 |

| Malvidin 3-glucoside | 8.1 ± 3.6 | 11.2 ± 0.5 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | - | 1.6 ± 0.2 | 23.91 ± 2.59 | 47.42 ± 0.73 |

| Cyanidin-3,5-diglucoside | 4.8 ± 1.0 | 5.6 ± 1.0 | - | 11.8 ± 0.1 | 38.0 ± 0.6 | 785.53 ± 39.56 | 152.02 ± 6.98 |

| Cyanidin 3-glucoside | 5.2 ± 3.2 | 8.0 ± 0.3 | 3.0 ± 0.0 | 1.4 ± 0.1 | 32.7 ± 0.5 | 21.72 ± 4.17 | 7.17 ± 0.59 |

| Delphinidin 3-glucoside | 3.3 ± 2.8 | 6.0 ± 1.2 | - | 11.7 ± 0.2 | 73.7 ± 1.2 | 17.79 ± 1.01 | 12.15 ± 0.09 |

| Peonidin 3-glucoside | 2.2 ± 1.0 | 3.0 ± 0.1 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 0.2 ± 0.0 | 2.45 ± 0.66 | 10.84 ± 0.11 |

| Pelargonidin 3-glucoside | 2.4 ± 1.4 | 3.6 ± 0.4 | - | 6.7 ± 0.1 | 6.7 ± 0.1 | - | - |

| Gallic acid | 2.3 ± 0.4 | 2.8 ± 0.5 | 1.8 ± 0.1 | 13.6 ± 0.1 | 10.5 ± 0.8 | 16.96 ± 0.39 | 11.51 ± 0.10 |

| Caffeic acid | 15.7 ± 1.0 | 17.2 ± 1.6 | 8.6 ± 0.1 | 35.8 ± 0.5 | 28.9 ± 0.4 | 29.95 ± 1.57 | 14.08 ± 0.17 |

| Cinnamic acid | 1.2 ± 0.7 | 2.0 ± 0.2 | 0.5 ± 0.0 | 0.6 ± 0.2 | 1.9 ± 0.1 | - | - |

| Chlorogenic acid | 2.3 ± 0.1 | 2.5 ± 0.3 | 4.1 ± 0.1 | 8.3 ± 0.3 | 21.3 ± 0.6 | - | - |

| p-Coumaric acid | 1.4 ± 0.0 | 1.7 ± 0.1 | 2.6 ± 0.1 | 4.5 ± 0.4 | 9.0 ± 0.1 | 11.23 ± 0.16 | 10.73 ± 0.51 |

| Kaempferol | 0.9 ± 0.2 | 1.2 ± 0.2 | - | - | - | 2.67 ± 0.02 | 3.01 ± 0.67 |

| Myricetin | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | - | - | - | 7.99 ± 0.99 | 6.98 ± 0.90 |

| Isorhamnetin | 1.2 ± 0.6 | 1.6 ± 0.2 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Rutin | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 1.8 ± 0.3 | - | - | - | . | - |

| Quercetin | 0.10 ± 0.00 | 0.17 ± 0.06 | - | - | - | 3.91 ± 0.08 | 4.27 ± 0.54 |

| DPPH (TE mmol/L) | - | - | - | - | - | 54.19 ± 0.24 | 40.76 ± 0.71 |

| ABTS (TE mmol/L) | - | - | - | - | - | 51.90 ± 0.33 | 31.09 ± 0.17 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cosme, F.; Pinto, T.; Vilela, A. Phenolic Compounds and Antioxidant Activity in Grape Juices: A Chemical and Sensory View. Beverages 2018, 4, 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages4010022

Cosme F, Pinto T, Vilela A. Phenolic Compounds and Antioxidant Activity in Grape Juices: A Chemical and Sensory View. Beverages. 2018; 4(1):22. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages4010022

Chicago/Turabian StyleCosme, Fernanda, Teresa Pinto, and Alice Vilela. 2018. "Phenolic Compounds and Antioxidant Activity in Grape Juices: A Chemical and Sensory View" Beverages 4, no. 1: 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages4010022

APA StyleCosme, F., Pinto, T., & Vilela, A. (2018). Phenolic Compounds and Antioxidant Activity in Grape Juices: A Chemical and Sensory View. Beverages, 4(1), 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages4010022