A Rising Tide of Green: Unpacking Predictors of New Zealand Consumers’ Willingness to Drink, Pay a Price Premium, and Promote Micro-Algae-Based Beverages

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review to Underpin the Conceptual Model and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Food Neophobia and Food Neophilia

2.2. Algae Involvement

2.3. Perceived Importance of Product Characteristics for Well-Being, Nutrition, and Sustainability

3. Methods

4. Results and Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Anusha Siddiqui, S.; Bahmid, N.A.; Mahmud, C.M.; Boukid, F.; Lamri, M.; Gagaoua, M. Consumer acceptability of plant-, seaweed-, and insect-based foods as alternatives to meat: A critical compilation of a decade of research. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 63, 6630–6651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maksan, M.T.; Matulić, D.; Mesić, Ž.; Memery, J. Segmenting and profiling seaweed consumers: A cross-cultural comparison of Australia, the United Kingdom and Croatia. Food Qual. Prefer. 2025, 122, 105305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrzypczyk, V.M.; Callahan, D.L.; Francis, D.S.; Bellgrove, A. Australian brown seaweeds as a source of essential dietary minerals. J. Appl. Phycol. 2024, 36, 797–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, M.; Paul, N.; Birch, D.; Swanepoel, L. Factors Influencing the Consumption of Seaweed amongst Young Adults. Foods 2022, 11, 3052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birch, D.; Skallerud, K.; Paul, N. Who eats seaweed? An Australian perspective. J. Int. Food Agribus. Mark. 2019, 31, 329–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabitti, N.S.; Bayudan, S.; Laureati, M.; Neugart, S.; Schouteten, J.J.; Apelman, L.; Sandvik, P. Snacks from the sea: A cross-national comparison of consumer acceptance for crackers added with algae. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2024, 250, 2193–2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villaró-Cos, S.; Sánchez, J.L.G.; Acién, G.; Lafarga, T. Research trends and current requirements and challenges in the industrial production of spirulina as a food source. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 143, 104280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Embling, R.; Neilson, L.; Randall, T.; Mellor, C.; Lee, M.D.; Wilkinson, L.L. ‘Edible seaweeds’ as an alternative to animal-based proteins in the UK: Identifying product beliefs and consumer traits as drivers of consumer acceptability for macroalgae. Food Qual. Prefer. 2022, 100, 104613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, L.J.G.; Souza, A.M.; Lopes, P.F.; Jacob, M.C.M. Food macroalgae: Scoping review of aspects related to research and consumption. J. Appl. Phycol. 2024, 36, 3475–3488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotman, V.; Jeffs, A. The Aquaculture and Market Opportunities for New Zealand Seaweed Species. Report Prepared For: The Nature Conservancy. 2021. Available online: https://www.aquaculturescience.org/aquaculture-and-marketing-opportunities-nz-seaweed/ (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Birch, D.; Skallerud, K.; Paul, N.A. Who are the future seaweed consumers in a Western society? Insights from Australia. Br. Food J. 2019, 121, 603–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Davis, C.V.; Noll, A.L.; Bernier, R.; Labbe, R. US consumer preferences and attitudes toward seaweed and value-added products. Agribusiness 2024, 40, 699–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Losada-Lopez, C.; Dopico, D.C.; Faina-Medin, J.A. Neophobia and seaweed consumption: Effects on consumer attitude and willingness to consume seaweed. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2021, 24, 100338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, R.; McSweeney, M.B. Do Consumers Want Seaweed in Their Food? A Study Evaluating Emotional Responses to Foods Containing Seaweed. Foods 2021, 10, 2737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govaerts, F.; Olsen, S.O. Environmental values and self-identity as a basis for identifying seaweed consumer segments in the UK. Br. Food J. 2024, 126, 1456–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redway, M.L.; Combet, E. Seaweed as food: Survey of the UK market and appraisal of opportunities and risks in the context of iodine nutrition. Br. Food J. 2023, 125, 3601–3622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafarga, T.; Rodríguez-Bermúdez, R.; Morillas-España, A.; Villaró, S.; García-Vaquero, M.; Morán, L.; Acién-Fernández, F.G. Consumer knowledge and attitudes towards microalgae as food: The case of Spain. Algal Res. 2021, 54, 102174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinrich, R.; Elshiewy, O. A cross-country analysis of how food-related lifestyles impact consumers’ attitudes towards microalgae consumption. Algal Res. 2023, 70, 102999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, J.; Cardoso, C.; Bandarra, N.M.; Afonso, C. Microalgae as healthy ingredients for functional food: A review. Food Funct. 2017, 8, 2672–2685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. Soft Drinks—New Zealand. 2025. Available online: https://www.statista.com/outlook/cmo/non-alcoholic-drinks/soft-drinks/new-zealand (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- Widyaswari, S.G.; Amir, N. A review: Bioactive compounds of macroalgae and their application as functional beverages. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 679, 012002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stunda-Zujeva, A.; Berele, M. Algae as a Functional Food: A Case Study on Spirulina. In Value-Added Products from Algae; Abomohra, A., Ende, S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellor, C.; Embling, R.; Neilson, L.; Randall, T.; Wakeham, C.; Lee, M.D.; Wilkinson, L.L. Consumer Knowledge and Acceptance of “Algae” as a Protein Alternative: A UK-Based Qualitative Study. Foods 2022, 11, 1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rombach, M.; Botero, J.; Dean, D.L. Finding Nori—Understanding Key Factors Driving US Consumers’ Commitment for Sea-Vegetable Products. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- StatsNZ. Pacific Peoples Ethnic Group. Available online: https://www.stats.govt.nz/tools/2018-census-ethnic-group-summaries/pacific-peoples (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- Frost, H.; Te Morenga, L.; Mackay, S.; McKerchar, C.; Egli, V. Impact of unhealthy food/drink marketing exposure to children in New Zealand: A systematic narrative review. Health Promot. Int. 2025, 40, daaf021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, M.; Crawford, R. Managing time, spending time: Retail trading hours and industriousness in Australia. Hist. Aust. 2025, 22, 282–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, C.; Backholer, K.; Monaghan, J.; Parker, K.; Relf, C.; Wallace, T.; Zorbas, C. Comparing regional Australian fruit and vegetable prices according to growing location and retail characteristics. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2025, 49, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, A.M.; Vonasch, A.; Prayag, G.; Smith, J. Zero-alcohol beverage aisle placement and social norms around alcohol: A cultural perspective from Aotearoa New Zealand. Health Mark. Q. 2025, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeger, S.R.; Chheang, S.L.; Jin, D.; Ryan, G.; Worch, T. The negative influence of food neophobia on food and beverage liking: Time to look beyond extreme groups analysis? Food Qual. Prefer. 2021, 92, 104217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabitti, N.S.; Sandvik, P.; Neugart, S.; Schouteten, J.J.; Laureati, M. Green color drives rejection of crackers added with algae in children but not in adults. Food Qual. Prefer. 2025, 127, 105461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duradoni, M.; Baroni, M.; Fiorenza, M.; Bellotti, M.; Neri, G.; Guazzini, A. Readiness to Change and the Intention to Consume Novel Foods: Evidence from Linear Discriminant Analysis. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogueva, D.; Marinova, D. Will Australians Eat Alternative Proteins? Foods 2025, 14, 1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bánáti, D.; Varga, K.; Bogueva, D. Consumer Perception of Algae and Algae-Based Products. In Consumer Perceptions and Food; Bogueva, D., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, M.L.; Olsen, K.; Jensen, P.E. Consumer acceptance of microalgae as a novel food—Where are we now? And how to get further. Physiol. Plant. 2024, 176, e14337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeger, S.R.; Rasmussen, M.A.; Prescott, J. Relationships between food neophobia and food intake and preferences: Findings from a sample of New Zealand adults. Appetite 2017, 116, 410–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Cong, L.; Mirosa, M.; Hou, Y.; Bremer, P. Food Technology Neophobia Scales in cross-national context: Consumers’ acceptance of food technologies between Chinese and New Zealand. J. Food Sci. 2023, 88, 3551–3561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahyuningtyas, A.S.H.; Abidin, Z.; Putri, W.D.R.; Maligan, J.M.; Berlian, G.O.; Ningrum, P.F.W. Consumer’s willingness to try new microalgae-based food in Indonesia. J. Agric. Food Res. 2024, 18, 101367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N.; Yeasmen, N.; Dube, L.; Orsat, V. Rise of plant-based beverages: A consumer-driven perspective. Food Rev. Int. 2024, 40, 3315–3341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegrist, M.; Hartmann, C.; Keller, C. Antecedents of food neophobia and its association with eating behavior and food choices. Food Qual. Prefer. 2013, 30, 293–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeger, S.R.; Chheang, S.L.; Prescott, J. Variations in the Strength of Association between Food Neophobia and Food and Beverage Acceptability: A Data-Driven Exploratory Study of an Arousal Hypothesis. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaeger, S.R.; Giacalone, D. Barriers to consumption of plant-based beverages: A comparison of product users and non-users on emotional, conceptual, situational, conative and psychographic variables. Food Res. Int. 2021, 144, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Toffoli, A.; Spinelli, S.; Monteleone, E.; Arena, E.; Di Monaco, R.; Endrizzi, I.; Gallina Toschi, T.; Laureati, M.; Napolitano, F.; Torri, L. Influences of Psychological Traits and PROP Taster Status on Familiarity with and Choice of Phenol-Rich Foods and Beverages. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idowu-Adebayo, F.; Fogliano, V.; Oluwamukomi, M.O.; Oladimeji, S.; Linnemann, A.R. Food neophobia among Nigerian consumers: A study on attitudes towards novel turmeric-fortified drinks. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2021, 101, 3246–3256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meeprom, S.; Sathatip, P.; Leruksa, C. Understanding Generation Z customers’ citizenship behaviour in relation to cannabis-infused food and beverage experiences. Young Consum. 2025, 26, 332–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Barón, S.E.; Carmona-Escutia, R.P.; Herrera-López, E.J.; Leyva-Trinidad, D.A.; Gschaedler-Mathis, A. Consumers’ Drivers of Perception and Preference of Fermented Food Products and Beverages: A Systematic Review. Foods 2025, 14, 713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rombach, M.; Lucock, X.; Dean, D.L. No Cow? Understanding US Consumer Preferences for Plant-Based over Regular Milk-Based Products. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Lee, D.; Choi, J.W.; Moon, J. Understanding the consumption of plant-based drink in South Korea: Drinking situations and food pairings. J. Int. Food Agribus. Mark. 2024, 37, 515–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonetti, G.G.; van Hooven, C.; Onorati, M.G. Planting Seeds of Change in Foodstyles: Growing Brand Strategies to Foster Plant-Based Alternatives Through Online Platforms. Gastronomy 2024, 2, 169–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiitii, U.; Paul, N.; Burkhart, S.; Larson, S.; Swanepoel, L. Traditional Knowledge and Modern Motivations for Consuming Seaweed (Limu) in Samoa. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salgado, M.J.G.; Rosario, I.L.d.S.; de Oliveira Almeida, A.C.; Rekowsky, B.S.d.S.; Paim, U.M.; Otero, D.M.; de Oliveira Mamede, M.E.; da Costa, M.P. Buffalo Whey-Based Cocoa Beverages with Unconventional Plant-Based Flours: The Effect of Information and Taste on Consumer Perception. Beverages 2023, 9, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rombach, M.; Botero, J.; Dean, D.L. Kelp Wanted? Understanding the Drivers of US Consumers’ Willingness to Buy and Their Willingness to Pay a Price Premium for Sea Vegetables. Gastronomy 2023, 1, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.; Geada, P.; Pereira, R.N.; Teixeira, J.A. Microalgae biomass—A source of sustainable dietary bioactive compounds towards improved health and well-being. Food Chem. Adv. 2025, 6, 100926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masih, I.S. The Health Benefits of Spirulina: A Superfood for the Modern Age. Soc. Sci. Rev. Arch. 2025, 3, 608–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastasiou, K.; Hadjikakou, M.; Geyik, O.; Hendrie, G.A.; Baker, P.; Pinter, R.; Lawrence, M. A quantitative environmental impact assessment of Australian ultra-processed beverages and impact reduction scenarios. Public Health Nutr. 2025, 28, e51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fantechi, T.; Contini, C.; Casini, L. Pasta goes green: Consumer preferences for spirulina-enriched pasta in Italy. Algal Res. 2023, 75, 103275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oktafika, R.A.; Widyaningrum, D. Consumer preferences for ready to drink Chlorella-enriched milk beverages using the conjoint analysis. AIP Conf. Proc. 2024, 2867, 020033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo, H.H.; Tran, K.D.; Le-Thi, L.; Nguyen-Thi, N.N.; Nguyen-Van, T.; Dinh-Thi, T.V.; Vu-Thi, T. The Effect of the Addition of Spirulina spp. on the Quality Properties, Health Benefits, and Sensory Evaluation of Green Tea Kombucha. Food Biophys. 2024, 19, 911–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andaregie, A.; Shimura, H.; Chikasada, M.; Sasaki, S.; Sato, S.; Addisu, S.; Takagi, I. Intention of consumers dwelling in urban areas of Ethiopia to consume Spirulina-fortified bread. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2024, 11, 2366434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andaregie, A.; Sasaki, S.; Shimura, H.; Chikasada, M.; Sato, S.; Addisu, S.; Takagi, I. Promoting Spirulina-enriched bread for primary school children in Ethiopia: Assessing parental willingness to purchase through information nudging. Appl. Food Res. 2024, 4, 100403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, A.J.; Hauser, D.J.; Rosenzweig, C.; Jaffe, S.; Robinson, J.; Litman, L. Using market-research panels for behavioral science: An overview and tutorial. Adv. Methods Pract. Psychol. Sci. 2023, 6, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leipold, F.M.; Kieslich, P.J.; Henninger, F.; Fernández-Fontelo, A.; Greven, S.; Kreuter, F. Detecting respondent burden in online surveys: How different sources of question difficulty influence cursor movements. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 2025, 43, 191–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pliner, P.; Hobden, K. Development of a scale to measure the trait of food neophobia in humans. Appetite 1992, 19, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiedenroth, C.F.; Otter, V. Who Are the Superfoodies? New Healthy Luxury Food Products and Social Media Marketing Potential in Germany. Foods 2021, 10, 2907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hair, J.E.; Hult, G.T.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.A. Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 3rd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosikyan, S.; Dolan, R.; Corsi, A.M.; Bastian, S. A systematic literature review and future research agenda to study consumer acceptance of novel foods and beverages. Appetite 2024, 203, 107655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucas, B.F.; Brunner, T.A. Factors influencing the willingness to purchase and consume microalgae-based foods: An exploratory consumer study. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2024, 37, 100974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiedenroth, C.F.; Otter, V. Can new healthy luxury food products accelerate short food supply chain formation via social media marketing in high-income countries? Agric. Food Econ. 2022, 10, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, P.K.; Tai Wai, K.; Abdullah, S.I.N.W.; Ow, M.W.; Wong, K.K.S. Eating with a purpose: Development and motivators for consumption of superfood. Malays. J. Consum. Fam. Econ. 2020, 24, 207–242. [Google Scholar]

- Latham, E. Unravelling the food narratives of Aotearoa New Zealand: Moving on from Pavlova and Lamingtons. Local J. Pac. Food Stud. 2021, 8, 89–115. [Google Scholar]

- Aboelenien, A.; Baudet, A.; Chow, A.M. ‘You need to change how you consume’: Ethical influencers, their audiences and their linking strategies. J. Mark. Manag. 2023, 39, 1043–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Frequency | Percentage (%) | NZ Census | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age Group | |||

| 18–24 years old | 62 | 14.2 | 12.2 |

| 25–34 years old | 79 | 18.1 | 18.4 |

| 35–44 years old | 72 | 16.5 | 16.3 |

| 45–54 years old | 77 | 17.6 | 17.5 |

| 55–64 years old | 62 | 14.2 | 15.7 |

| 65 years old and older | 85 | 19.5 | 19.9 |

| Total | 437 | 100 | 100 |

| Household Income Group (per Year in NZD) | |||

| NZD 0 to NZD 24,999 | 50 | 11.4 | 19 |

| NZD 25,000 to NZD 49,999 | 125 | 28.6 | 40 |

| NZD 50,000 to NZD 74,999 | 116 | 26.5 | 24 |

| NZD 75,000 to NZD 99,999 | 65 | 14.9 | 11 |

| NZD 100,000 or higher | 81 | 18.5 | 6 |

| Total | 437 | 100 | 100 |

| Gender Group | |||

| Female | 224 | 51.3 | 50.7 |

| Male | 213 | 48.8 | 49.4 |

| Prefer not to say | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 437 | 100 | 100 |

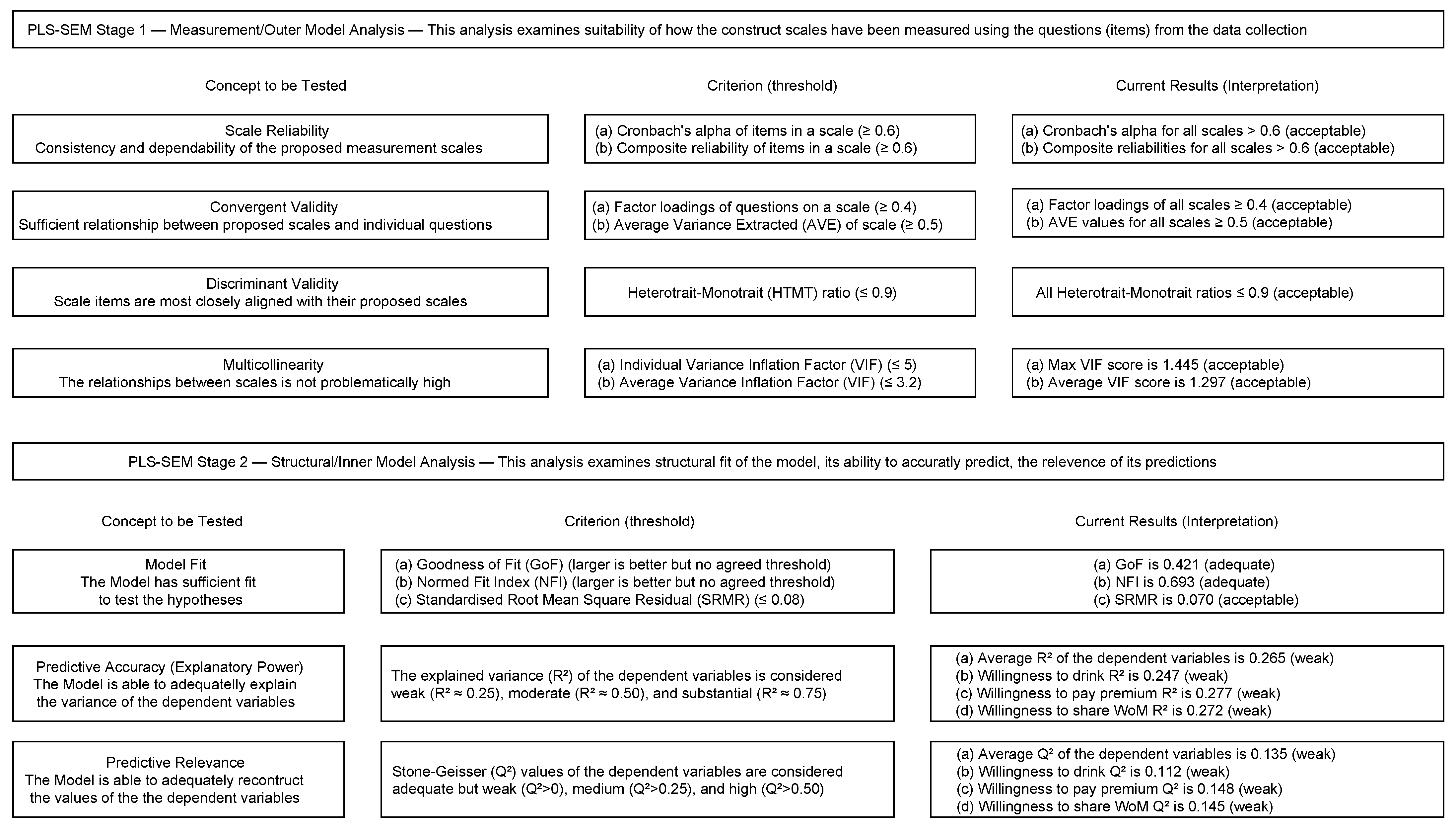

| Scales and Items | Factor Loadings | Cronbach’s Alpha | Composite Reliability | Average Variance Extracted |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food Neophilia | 0.727 | 0.828 | 0.549 | |

| I like to try new ethnic restaurants. | 0.762 | |||

| I like foods from different cultures. | 0.771 | |||

| At dinner parties, I will try new foods. | 0.767 | |||

| I will eat almost anything. | 0.838 | |||

| Food Neophobia | 0.792 | 0.865 | 0.616 | |

| I don’t trust new foods. | 0.799 | |||

| If I don’t know what a food is, I won’t try it. | 0.740 | |||

| Ethnic food looks too weird to eat. | 0.779 | |||

| I am afraid to eat things I have never had before. | 0.634 | |||

| Algae Involvement | 0.734 | 0.835 | 0.567 | |

| I have been foraging for algae. | 0.801 | |||

| I am committed to food processing and food preserving. | 0.608 | |||

| I have watched YouTube videos about algae production. | 0.840 | |||

| I know how to identify algae. | 0.814 | |||

| Perceived importance of product characteristics for well-being, nutrition, and sustainability | 0.872 | 0.889 | 0.528 | |

| Healthfulness | 0.794 | |||

| Nutritiousness | 0.683 | |||

| Contains Omega-3 acids | 0.636 | |||

| Calories (low) | 0.824 | |||

| Contains iodine | 0.735 | |||

| Sustainability | 0.649 | |||

| Product from the seafood industry | 0.735 | |||

| Contains protein | 0.735 | |||

| Willingness to drink micro-algae-based beverages | 0.806 | 0.885 | 0.721 | |

| Micro-algae-based smoothy | 0.685 | |||

| Micro-algae-based tea | 0.826 | |||

| Micro-algae-based cuppa soup | 0.783 | |||

| Willingness to pay a price premium for micro-algae-based beverages | 0.646 | 0.810 | 0.588 | |

| Micro-algae-based smoothy | 0.776 | |||

| Micro-algae-based tea | 0.886 | |||

| Micro-algae-based cuppa soup | 0.880 | |||

| Willingness to spread word of mouth for micro-algae-based beverages | 0.813 | 0.890 | 0.729 | |

| Micro-algae-based smoothy | 0.808 | |||

| Micro-algae-based tea | 0.890 | |||

| Micro-algae-based cuppa soup | 0.862 | |||

| HTMT | A | B | C | D | E | F |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (A) Food neophilia | ||||||

| (B) Food neophobia | 0.663 | |||||

| (C) Algae involvement | 0.163 | 0.254 | ||||

| (D) Perceived importance of product characteristics | 0.332 | 0.177 | 0.329 | |||

| (E) Willingness to pay a price premium for micro-algae-based beverages | 0.200 | 0.118 | 0.503 | 0.195 | ||

| (F) Willingness to drink micro-algae-based beverages | 0.444 | 0.307 | 0.284 | 0.288 | 0.701 | |

| (G) Willingness to spread word of mouth for micro-algae-based beverages | 0.309 | 0.100 | 0.407 | 0.338 | 0.753 | 0.814 |

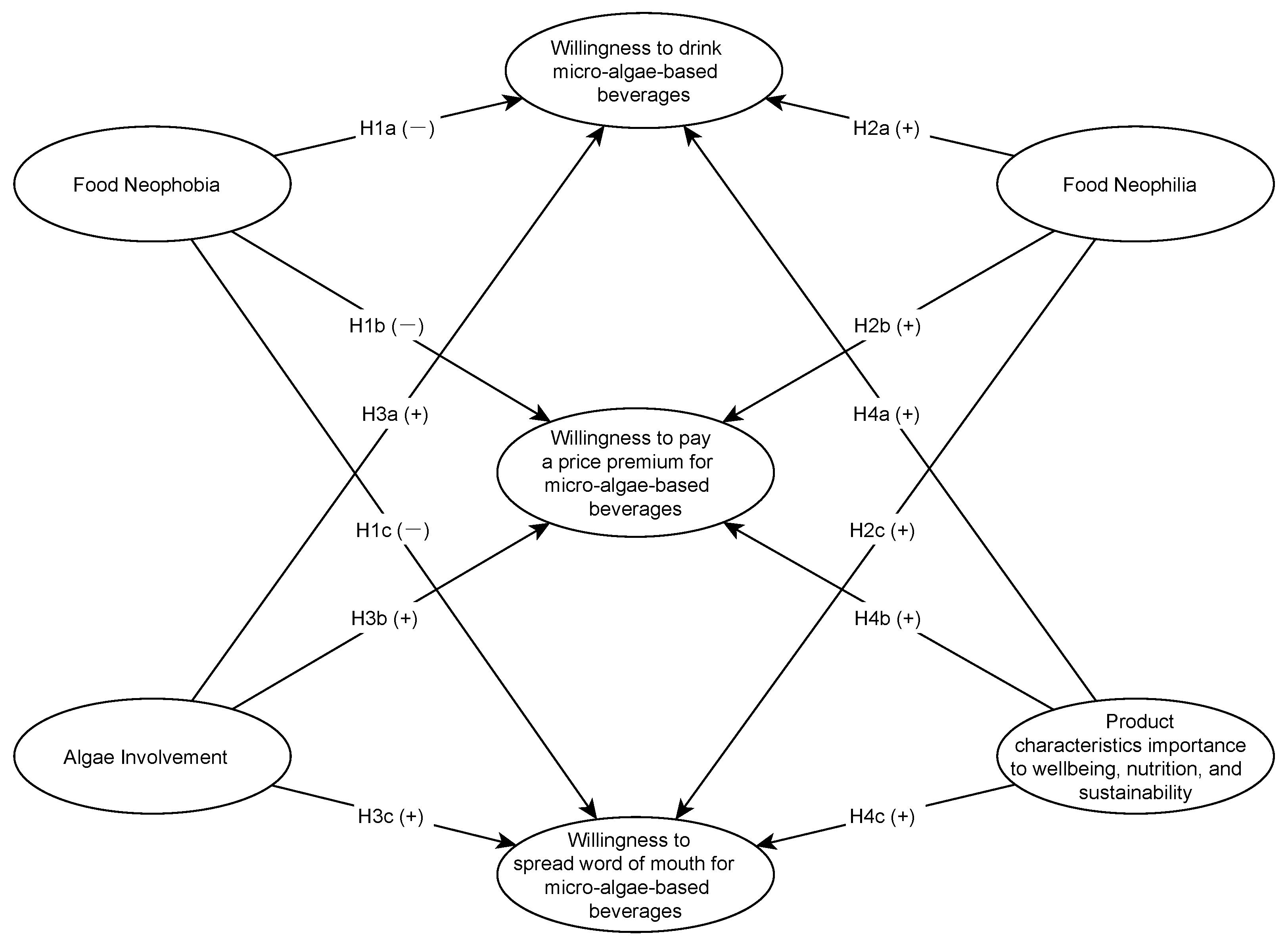

| Hypothesised Relationship | Coefficient | T Statistics | p Values |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1a. Food neophobia → Willingness to drink micro-algae-based beverages. | −0.138 | 2.396 | 0.017 |

| H1b. Food neophobia → Willingness to pay a price premium for micro-algae-based beverages. | 0.087 | 1.539 | 0.124 |

| H1c. Food neophobia → Willingness to spread word of mouth for micro-algae-based beverages. | 0.002 | 0.035 | 0.972 |

| H2a. Food neophilia → Willingness to drink micro-algae-based beverages. | 0.194 | 3.212 | 0.001 |

| H2b. Food neophilia → Willingness to pay a price premium for micro-algae-based beverages. | 0.142 | 2.600 | 0.009 |

| H2c. Food neophilia → Willingness to spread word of mouth for micro-algae-based beverages. | 0.165 | 2.755 | 0.006 |

| H3a. Algae involvement → Willingness to drink micro-algae-based beverages. | 0.159 | 2.834 | 0.005 |

| H3b. Algae involvement → Willingness to pay a price premium for micro-algae-based beverages. | 0.352 | 7.132 | 0.000 |

| H3c. Algae involvement → Willingness to spread word of mouth for micro-algae-based beverages. | 0.249 | 4.715 | 0.000 |

| H4a. Perception of product attributes → Willingness to drink micro-algae-based beverages. | 0.113 | 1.807 | 0.071 |

| H4b. Perception of product attributes → Willingness to pay a price premium for micro-algae-based beverages. | 0.054 | 0.906 | 0.365 |

| H4c. Perception of product attributes → Willingness to spread word of mouth for micro-algae-based beverages. | 0.184 | 3.085 | 0.002 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rombach, M.; Dean, D.L. A Rising Tide of Green: Unpacking Predictors of New Zealand Consumers’ Willingness to Drink, Pay a Price Premium, and Promote Micro-Algae-Based Beverages. Beverages 2025, 11, 120. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages11040120

Rombach M, Dean DL. A Rising Tide of Green: Unpacking Predictors of New Zealand Consumers’ Willingness to Drink, Pay a Price Premium, and Promote Micro-Algae-Based Beverages. Beverages. 2025; 11(4):120. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages11040120

Chicago/Turabian StyleRombach, Meike, and David L Dean. 2025. "A Rising Tide of Green: Unpacking Predictors of New Zealand Consumers’ Willingness to Drink, Pay a Price Premium, and Promote Micro-Algae-Based Beverages" Beverages 11, no. 4: 120. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages11040120

APA StyleRombach, M., & Dean, D. L. (2025). A Rising Tide of Green: Unpacking Predictors of New Zealand Consumers’ Willingness to Drink, Pay a Price Premium, and Promote Micro-Algae-Based Beverages. Beverages, 11(4), 120. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages11040120