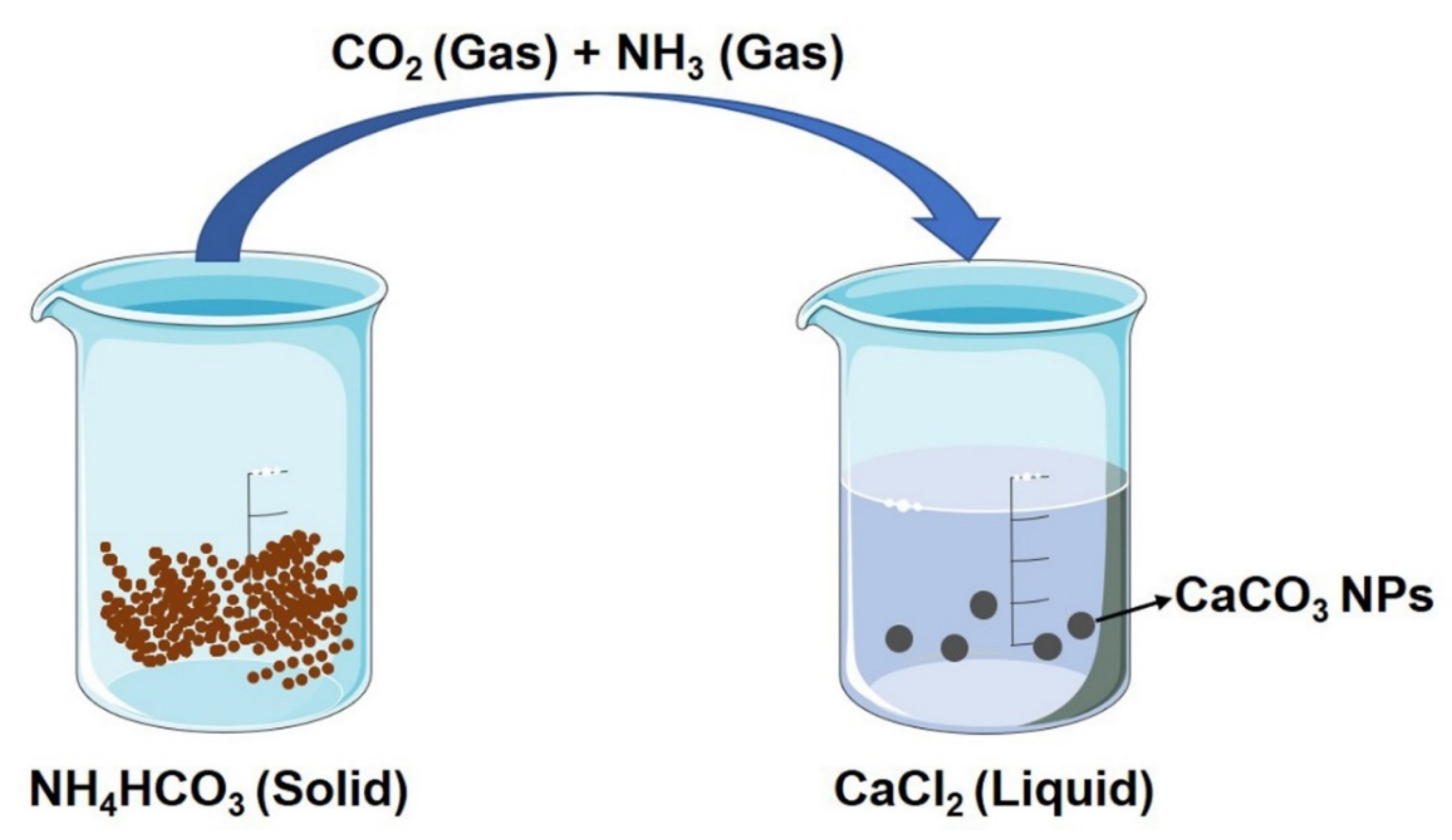

Recent Advances of Calcium Carbonate Nanoparticles for Biomedical Applications

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Advantages of CaCO3 NPs

2.1. Excellent Biocompatibility/Biodegradability and pH-Sensitive Property

2.2. Ease of Preparation and Surface Modification

3. The Preparation Methods and Controlled Release of CaCO3 NPs

3.1. Solution Precipitation Method

3.2. Microemulsion Method

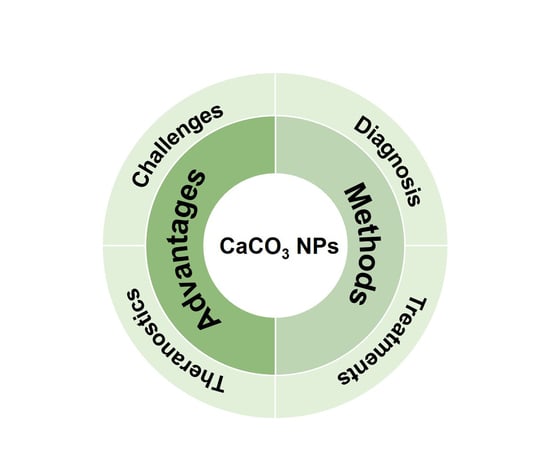

3.3. Gas Diffusion Method

3.4. Controlled Release of CaCO3 NPs

4. The Biomedical Applications of CaCO3 NPs

4.1. CaCO3 NPs for Diagnosis

4.2. CaCO3 NPs for Treatment

4.2.1. CaCO3 NPs as Carriers for Chemical Therapy

4.2.2. CaCO3 NPs as Carriers for Gene Therapy

4.2.3. CaCO3 NPs as Carriers for PTT/PDT

4.2.4. CaCO3 NPs as Ca2+ Generators for Immunotherapy

4.2.5. CaCO3 NP-Based Combination Therapy

4.3. CaCO3 NPs for Theranostic

4.3.1. US Imaging-Guided Therapy

4.3.2. FLI-Guided Therapy

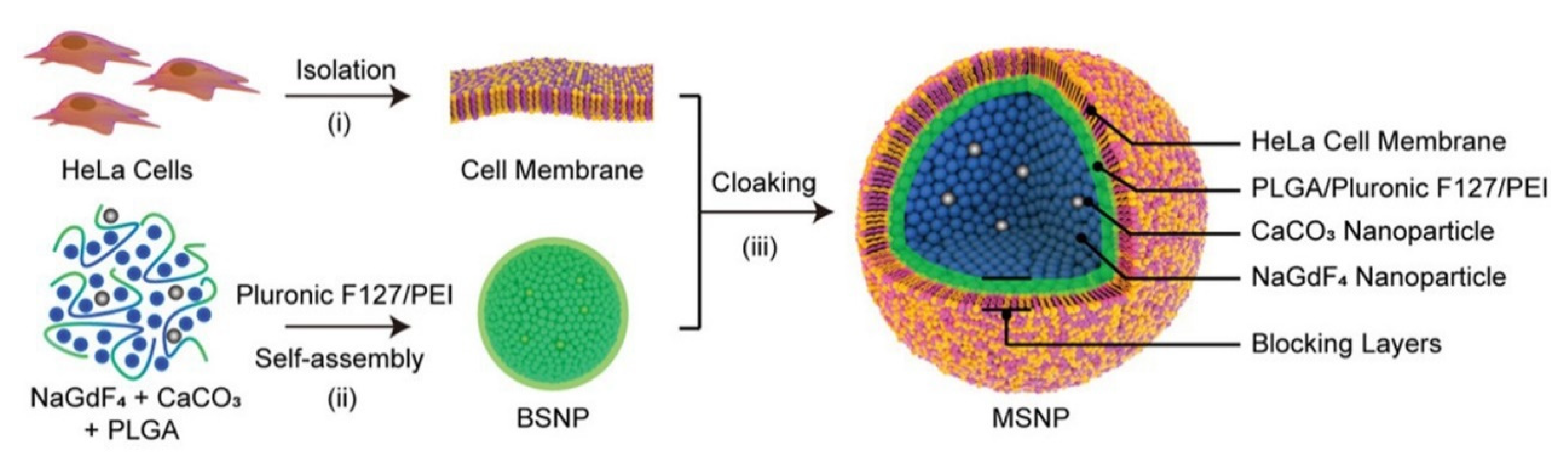

4.3.3. MRI-Guided Therapy

5. The Challenges and Recommendations for Future Studies of CaCO3 NPs

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Patra, J.K.; Das, G.; Fraceto, L.F.; Campos, E.V.R.; Rodriguez-Torres, M.d.P.; Acosta-Torres, L.S.; Diaz-Torres, L.A.; Grillo, R.; Swamy, M.K.; Sharma, S.; et al. Nano based drug delivery systems: Recent developments and future prospects. J. Nanobiotechnology 2018, 16, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, X.; Zaks, T.; Langer, R.; Dong, Y. Lipid nanoparticles for mRNA delivery. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2021, 6, 1078–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, K.K.; Koshy, P.; Yang, J.-L.; Sorrell, C.C. Preclinical Cancer Theranostics—From Nanomaterials to Clinic: The Missing Link. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2104199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, C.; Lin, J.; Fu, L.-H.; Huang, P. Calcium-based biomaterials for diagnosis, treatment, and theranostics. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018, 47, 357–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cartwright, J.H.E.; Checa, A.G.; Gale, J.D.; Gebauer, D.; Sainz-Díaz, C.I. Calcium Carbonate Polyamorphism and Its Role in Biomineralization: How Many Amorphous Calcium Carbonates Are There? Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 11960–11970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolf, S.E.; Leiterer, J.; Kappl, M.; Emmerling, F.; Tremel, W. Early Homogenous Amorphous Precursor Stages of Calcium Carbonate and Subsequent Crystal Growth in Levitated Droplets. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 12342–12347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, L.C.; Newcomb, C.J.; Kaltz, S.R.; Spoerke, E.D.; Stupp, S.I. Biomimetic Systems for Hydroxyapatite Mineralization Inspired By Bone and Enamel. Chem. Rev. 2008, 108, 4754–4783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, B.; Zhou, T.; Liu, J.; Shao, L. Involvement of Programmed Cell Death in Neurotoxicity of Metallic Nanoparticles: Recent Advances and Future Perspectives. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2016, 11, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Verma, A.; Teja, B.V.; Pandey, G.; Mittapelly, N.; Trivedi, R.; Mishra, P.R. An insight into functionalized calcium based inorganic nanomaterials in biomedicine: Trends and transitions. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2015, 133, 120–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Bian, Y.; Xiao, X.; Liu, B.; Ding, B.; Cheng, Z.; Ma, P.a.; Lin, J. Tumor Microenvironment-Responsive Cu/CaCO3-Based Nanoregulator for Mitochondrial Homeostasis Disruption-Enhanced Chemodynamic/Sonodynamic Therapy. Small 2022, 18, 2204047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Chen, T.; Wu, C.; Zhu, G.; Qiu, L.; Cui, C.; Hou, W.; Tan, W. Aptamer CaCO3 Nanostructures: A Facile, pH-Responsive, Specific Platform for Targeted Anticancer Theranostics. Chem. Asian J. 2015, 10, 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, S.; Lan, Y.; Fu, S.; Cheng, H.; Lu, Z.; Liu, G. Connecting Calcium-Based Nanomaterials and Cancer: From Diagnosis to Therapy. Nano-Micro Lett. 2022, 14, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueno, Y.; Futagawa, H.; Takagi, Y.; Ueno, A.; Mizushima, Y. Drug-incorporating calcium carbonate nanoparticles for a new delivery system. J. Control. Release 2005, 103, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Luo, Z.; Li, M.; Qu, Q.; Ma, X.; Yu, S.-H.; Zhao, Y. A Preloaded Amorphous Calcium Carbonate/Doxorubicin@Silica Nanoreactor for pH-Responsive Delivery of an Anticancer Drug. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 919–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, M.; Stark, W.J.; Loher, S.; Maciejewski, M.; Krumeich, F.; Baiker, A. Flame synthesis of calcium carbonate nanoparticles. Chem. Commun. 2005, 648–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, K.N.; Zuki, A.B.Z.; Ali, M.E.; Hussein, M.Z.B.; Noordin, M.M.; Loqman, M.Y.; Wahid, H.; Hakim, M.A.; Hamid, S.B.A. Facile synthesis of calcium carbonate nanoparticles from cockle shells. J. Nanomater. 2012, 2012, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafiu Kamba, A.; Ismail, M.; Tengku Ibrahim, T.A.; Zakaria, Z.A.B. A pH-Sensitive, Biobased Calcium Carbonate Aragonite Nanocrystal as a Novel Anticancer Delivery System. BioMed Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 587451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleki Dizaj, S.; Barzegar-Jalali, M.; Zarrintan, M.H.; Adibkia, K.; Lotfipour, F. Calcium carbonate nanoparticles as cancer drug delivery system. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2015, 12, 1649–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Mann, S. Emergent Nanostructures: Water-Induced Mesoscale Transformation of Surfactant-Stabilized Amorphous Calcium Carbonate Nanoparticles in Reverse Microemulsions. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2002, 12, 773–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.X.; Ding, J.; Xue, J.M. Synthesis of calcium carbonate capsules in water-in-oil-in-water double emulsions. J. Mater. Res. 2008, 23, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.K.; Foote, M.B.; Huang, L. Targeted delivery of EV peptide to tumor cell cytoplasm using lipid coated calcium carbonate nanoparticles. Cancer Lett. 2013, 334, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barhoum, A.; Rahier, H.; Abou-Zaied, R.E.; Rehan, M.; Dufour, T.; Hill, G.; Dufresne, A. Effect of Cationic and Anionic Surfactants on the Application of Calcium Carbonate Nanoparticles in Paper Coating. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 2734–2744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyjoo, Y.; Pareek, V.K.; Liu, J. Synthesis of micro and nano-sized calcium carbonate particles and their applications. J. Mater. Chem. A 2014, 2, 14270–14288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, A.M.; Vikulina, A.S.; Volodkin, D. CaCO(3) crystals as versatile carriers for controlled delivery of antimicrobials. J. Control. Release Off. J. Control. Release Soc. 2020, 328, 470–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vikulina, A.; Voronin, D.; Fakhrullin, R.; Vinokurov, V.; Volodkin, D. Naturally derived nano- and micro-drug delivery vehicles: Halloysite, vaterite and nanocellulose. New J. Chem. 2020, 44, 5638–5655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begum, G.; Reddy, T.N.; Kumar, K.P.; Dhevendar, K.; Singh, S.; Amarnath, M.; Misra, S.; Rangari, V.K.; Rana, R.K. In Situ Strategy to Encapsulate Antibiotics in a Bioinspired CaCO3 Structure Enabling pH-Sensitive Drug Release Apt for Therapeutic and Imaging Applications. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 22056–22063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Z.; Luo, Z.; Barth, N.D.; Meng, X.; Liu, H.; Bu, W.; All, A.; Vendrell, M.; Liu, X. In Vivo Tumor Visualization through MRI Off-On Switching of NaGdF4–CaCO3 Nanoconjugates. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, 1901851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, S.E.; Kang, S.S.; Tae, G. Nanosized Ultrasound Enhanced-Contrast Agent for in Vivo Tumor Imaging via Intravenous Injection. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 8409–8418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

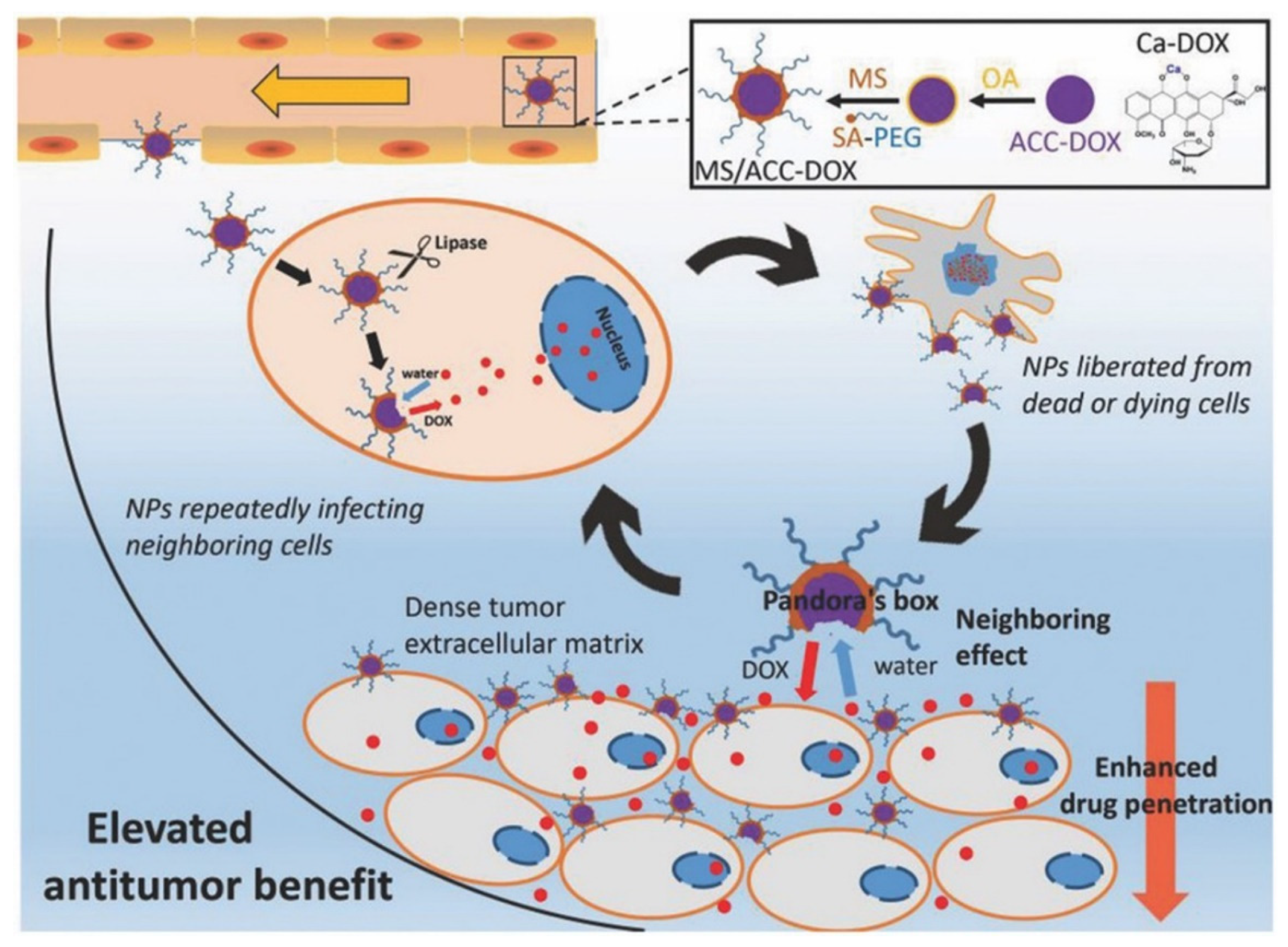

- Wang, C.; Chen, S.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Hu, F.; Sun, J.; Yuan, H. Lipase-Triggered Water-Responsive “Pandora’s Box” for Cancer Therapy: Toward Induced Neighboring Effect and Enhanced Drug Penetration. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1706407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, P.; Hou, M.; Sun, L.; Li, Q.; Zhang, L.; Xu, Z.; Kang, Y. Calcium-carbonate packaging magnetic polydopamine nanoparticles loaded with indocyanine green for near-infrared induced photothermal/photodynamic therapy. Acta Biomater 2018, 81, 242–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Wu, S.; Cheng, Y.; You, J.; Chen, Y.; Li, M.; He, C.; Zhang, X.; Yang, T.; Lu, Y.; et al. MiR-375 delivered by lipid-coated doxorubicin-calcium carbonate nanoparticles overcomes chemoresistance in hepatocellular carcinoma. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 2017, 13, 2507–2516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendell, J.R.; Al-Zaidy, S.A.; Rodino-Klapac, L.R.; Goodspeed, K.; Gray, S.J.; Kay, C.N.; Boye, S.L.; Boye, S.E.; George, L.A.; Salabarria, S.; et al. Current Clinical Applications of In Vivo Gene Therapy with AAVs. Mol. Ther. 2021, 29, 464–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Santa Chalarca, C.F.; Bockman, M.R.; Bruggen, C.V.; Grimme, C.J.; Dalal, R.J.; Hanson, M.G.; Hexum, J.K.; Reineke, T.M. Polymeric Delivery of Therapeutic Nucleic Acids. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 11527–11652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.W.; Liu, T.; Chen, Y.X.; Cheng, D.J.; Li, X.R.; Xiao, Y.; Feng, Y.L. Calcium carbonate nanoparticle delivering vascular endothelial growth factor-C siRNA effectively inhibits lymphangiogenesis and growth of gastric cancer in vivo. Cancer Gene Ther. 2008, 15, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Han, H.; Yang, W.; Ren, X.; Kong, X. Polyethyleneimine-modified calcium carbonate nanoparticles for p53 gene delivery. Regen. Biomater. 2016, 3, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; El-Sayed, I.H.; Qian, W.; El-Sayed, M.A. Cancer Cell Imaging and Photothermal Therapy in the Near-Infrared Region by Using Gold Nanorods. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 2115–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolmans, D.E.J.G.J.; Fukumura, D.; Jain, R.K. Photodynamic therapy for cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2003, 3, 380–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, R.S.; June, C.H.; Langer, R.; Mitchell, M.J. Delivery technologies for cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2019, 18, 175–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

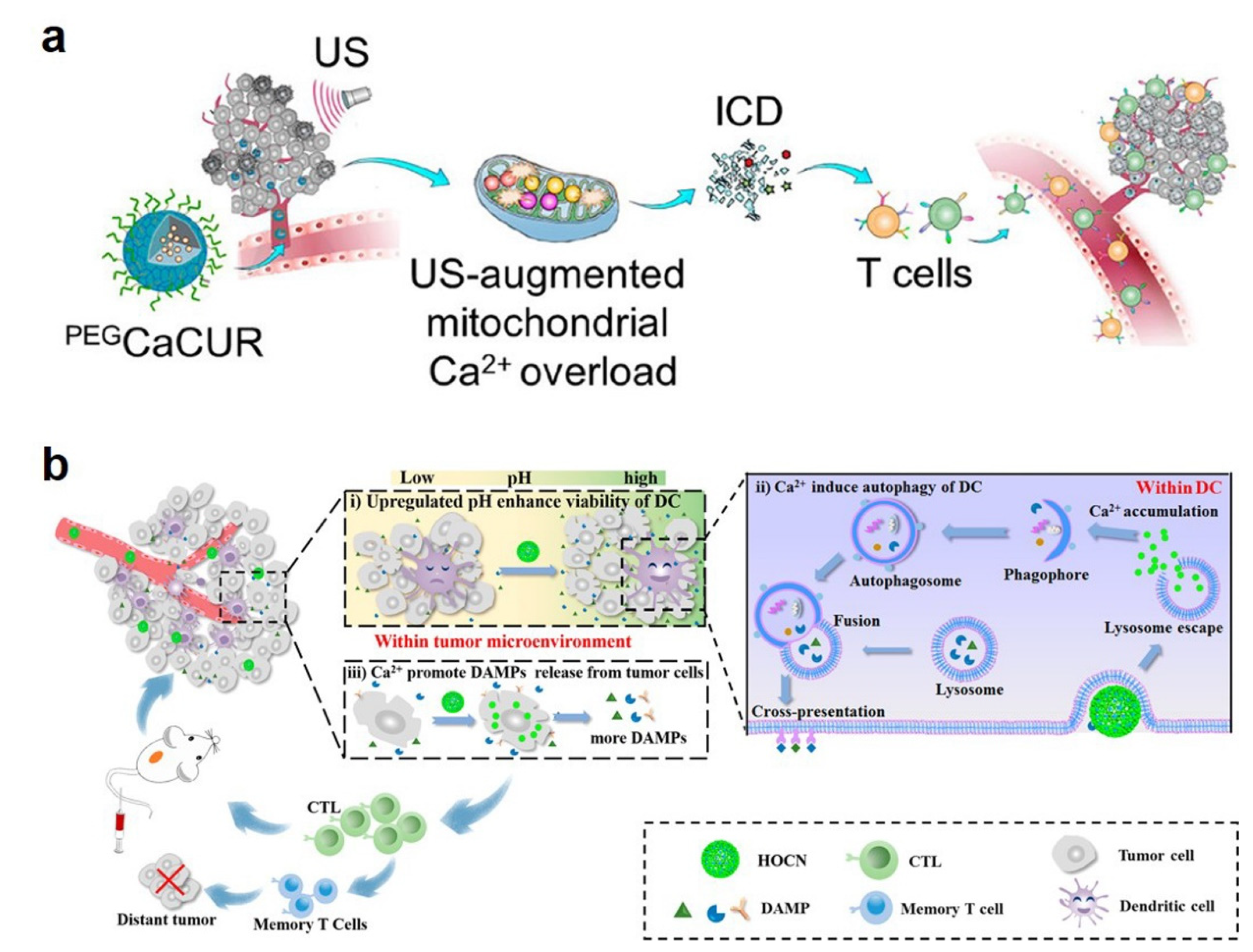

- Zheng, P.; Ding, B.; Jiang, Z.; Xu, W.; Li, G.; Ding, J.; Chen, X. Ultrasound-Augmented Mitochondrial Calcium Ion Overload by Calcium Nanomodulator to Induce Immunogenic Cell Death. Nano Lett. 2021, 21, 2088–2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, J.; Zhang, K.; Wang, B.; Wu, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, J.; Shi, J. Nanoenabled Disruption of Multiple Barriers in Antigen Cross-Presentation of Dendritic Cells via Calcium Interference for Enhanced Chemo-Immunotherapy. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 7639–7650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, A.L.; Hsu, C.; Chan, S.L.; Choo, S.P.; Kudo, M. Challenges of combination therapy with immune checkpoint inhibitors for hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Hepatol. 2020, 72, 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, P.; Li, M.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Y.; He, C.; Zhang, X.; Yang, T.; Lu, Y.; You, J.; Lee, R.J.; et al. Enhancing anti-tumor efficiency in hepatocellular carcinoma through the autophagy inhibition by miR-375/sorafenib in lipid-coated calcium carbonate nanoparticles. Acta Biomater 2018, 72, 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, F.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, X.; Liu, D.; Chen, D.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, L.; Santos, H.A.; Hai, M. Biodegradable Photothermal and pH Responsive Calcium Carbonate@Phospholipid@Acetalated Dextran Hybrid Platform for Advancing Biomedical Applications. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2016, 26, 6158–6169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lammers, T.; Aime, S.; Hennink, W.E.; Storm, G.; Kiessling, F. Theranostic Nanomedicine. Acc. Chem. Res. 2011, 44, 1029–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Min, K.H.; Min, H.S.; Lee, H.J.; Park, D.J.; Yhee, J.Y.; Kim, K.; Kwon, I.C.; Jeong, S.Y.; Silvestre, O.F.; Chen, X.; et al. pH-Controlled Gas-Generating Mineralized Nanoparticles: A Theranostic Agent for Ultrasound Imaging and Therapy of Cancers. ACS Nano 2015, 9, 134–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Zhang, W.; Liu, Z.; Guo, H.; Zhang, P. Smart responsive-calcium carbonate nanoparticles for dual-model cancer imaging and treatment. Ultrasonics 2020, 108, 106198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vavaev, E.S.; Novoselova, M.; Shchelkunov, N.M.; German, S.; Komlev, A.S.; Mokrousov, M.D.; Zelepukin, I.V.; Burov, A.M.; Khlebtsov, B.N.; Lyubin, E.V.; et al. CaCO3 Nanoparticles Coated with Alternating Layers of Poly-L-Arginine Hydrochloride and Fe3O4 Nanoparticles as Navigable Drug Carriers and Hyperthermia Agents. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2022, 5, 2994–3006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Q.; Zhang, W.; Yang, X.; Li, Y.; Hao, Y.; Zhang, H.; Hou, L.; Zhang, Z. pH/Ultrasound Dual-Responsive Gas Generator for Ultrasound Imaging-Guided Therapeutic Inertial Cavitation and Sonodynamic Therapy. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2018, 7, 1700957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, S.; Zhang, Y.; Li, D.; Shi, X.; Lin, G.; Liu, G. Gain an advantage from both sides: Smart size-shrinkable drug delivery nanosystems for high accumulation and deep penetration. Nano Today 2021, 36, 101038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhong, X.; Li, J.; Liu, Z.; Cheng, L. Inorganic nanomaterials with rapid clearance for biomedical applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 8669–8742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinawi, M. Disorders of Calcium Metabolism: Hypocalcemia and Hypercalcemia. Cureus 2021, 13, e12420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhao, P.; Tian, Y.; You, J.; Hu, X.; Liu, Y. Recent Advances of Calcium Carbonate Nanoparticles for Biomedical Applications. Bioengineering 2022, 9, 691. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering9110691

Zhao P, Tian Y, You J, Hu X, Liu Y. Recent Advances of Calcium Carbonate Nanoparticles for Biomedical Applications. Bioengineering. 2022; 9(11):691. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering9110691

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Pengxuan, Yu Tian, Jia You, Xin Hu, and Yani Liu. 2022. "Recent Advances of Calcium Carbonate Nanoparticles for Biomedical Applications" Bioengineering 9, no. 11: 691. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering9110691

APA StyleZhao, P., Tian, Y., You, J., Hu, X., & Liu, Y. (2022). Recent Advances of Calcium Carbonate Nanoparticles for Biomedical Applications. Bioengineering, 9(11), 691. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering9110691