Toward Nanodisc Tailoring for SANS Study of Membrane Proteins

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Preparation

2.1.1. Reagents and DMPC

2.1.2. Belt Proteins

2.1.3. Total Lipid Extraction

2.1.4. Polar Mixture Fractionation by Preparative HPLC

2.1.5. Fatty Acid Methyl Esters (FAMEs) Analysis by GC-FID

2.1.6. Nanodisc Assembly

2.2. SANS Measurements

2.3. SAXS Measurements

2.4. SAS Data Analysis Based on Analytical Models

2.4.1. SANS Data Fitting

2.4.2. SAXS Data Fitting

3. Results

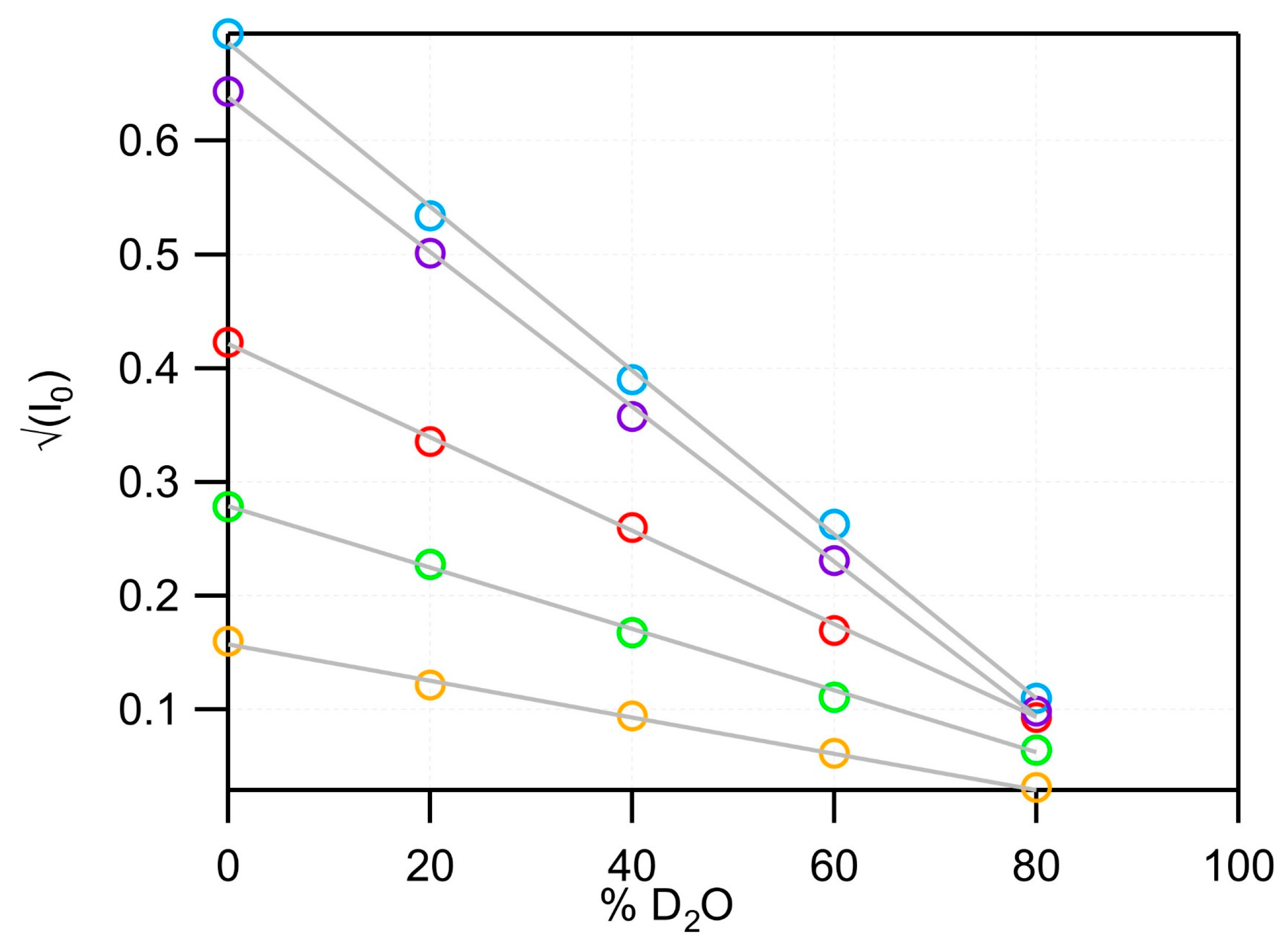

3.1. Protonated DMPC Nanodiscs

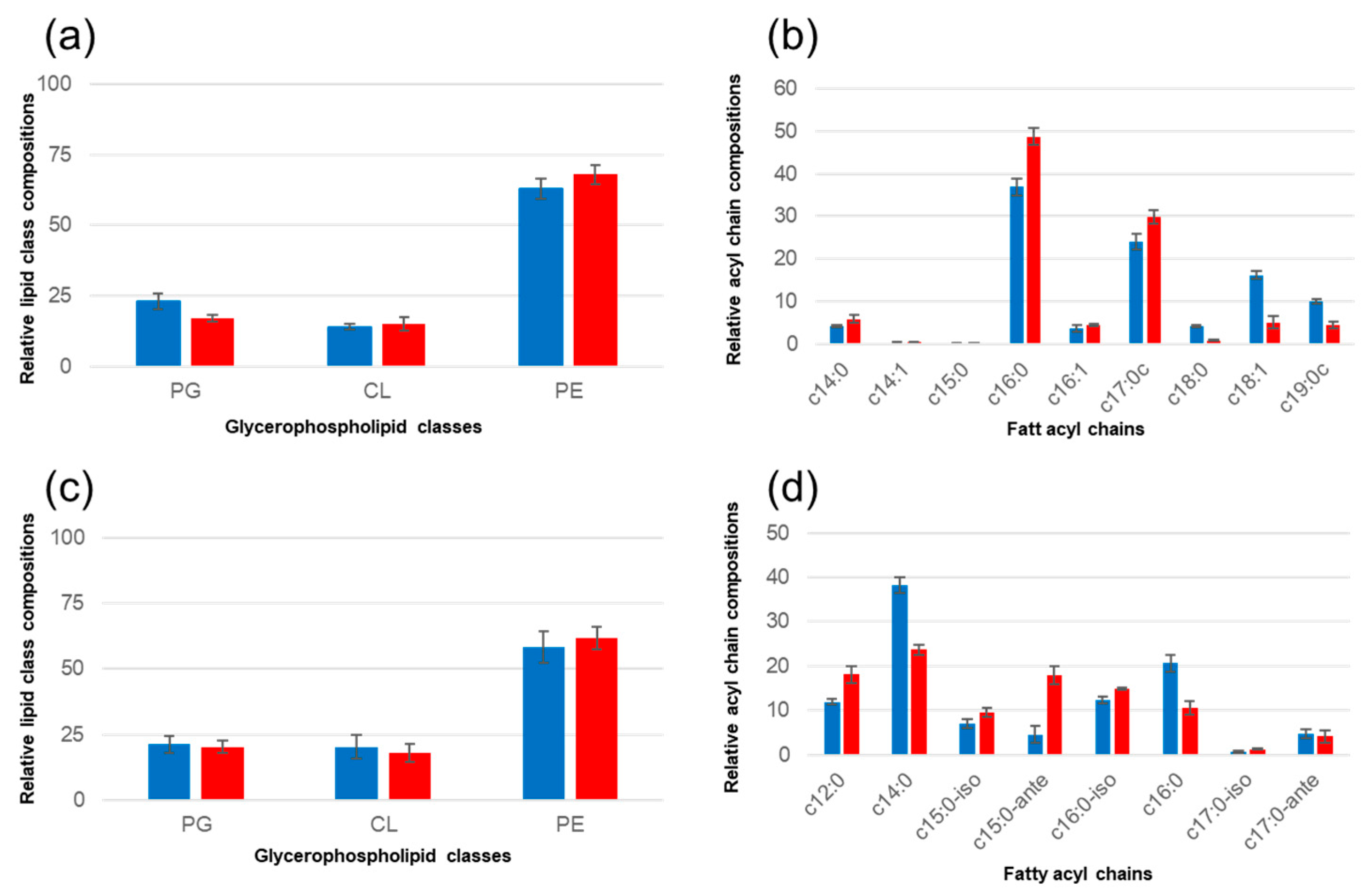

3.2. Protonated Natural Lipid Mixes Nanodiscs

3.3. Deuterated Nanodiscs

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SANS | Small-angle neutron scattering |

| SAXS | Small-angle X-ray scattering |

| HPLC | High-performance liquid chromatography |

| DMPC | Di-myristoyl-phosphatidyl-choline |

| EcLip | Escherichia coli total polar lipids |

| BsLip | Bacillus subtilis total polar lipids |

| GC-MS | Gas chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry |

References

- White, S.H. The Progress of Membrane Protein Structure Determination. Protein Sci. 2004, 13, 1948–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denisov, I.G.; Grinkova, Y.V.; Lazarides, A.A.; Sligar, S.G. Directed Self-Assembly of Monodisperse Phospholipid Bilayer Nanodiscs with Controlled Size. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 3477–3487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Kijac, A.Z.; Sligar, S.G.; Rienstra, C.M. Structural Analysis of Nanoscale Self-Assembled Discoidal Lipid Bilayers by Solid-State NMR Spectroscopy. Biophys. J. 2006, 91, 3819–3828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayburt, T.H.; Sligar, S.G. Membrane Protein Assembly into Nanodiscs. FEBS Lett. 2010, 584, 1721–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenkarev, Z.O.; Lyukmanova, E.N.; Paramonov, A.S.; Shingarova, L.N.; Chupin, V.V.; Kirpichnikov, M.P.; Blommers, M.J.J.; Arseniev, A.S. Lipid−Protein Nanodiscs as Reference Medium in Detergent Screening for High-Resolution NMR Studies of Integral Membrane Proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 5628–5629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Daday, C.; Gu, R.-X.; Cox, C.D.; Martinac, B.; De Groot, B.L.; Walz, T. Visualization of the Mechanosensitive Ion Channel MscS under Membrane Tension. Nature 2021, 590, 509–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golub, M.; Gätcke, J.; Subramanian, S.; Kölsch, A.; Darwish, T.; Howard, J.K.; Feoktystov, A.; Matsarskaia, O.; Martel, A.; Porcar, L.; et al. “Invisible” Detergents Enable a Reliable Determination of Solution Structures of Native Photosystems by Small-Angle Neutron Scattering. J. Phys. Chem. B 2022, 126, 2824–2833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midtgaard, S.R.; Darwish, T.A.; Pedersen, M.C.; Huda, P.; Larsen, A.H.; Jensen, G.V.; Kynde, S.A.R.; Skar-Gislinge, N.; Nielsen, A.J.Z.; Olesen, C.; et al. Invisible Detergents for Structure Determination of Membrane Proteins by Small-angle Neutron Scattering. FEBS J. 2018, 285, 357–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansen, N.T.; Bonaccorsi, M.; Bengtsen, T.; Larsen, A.H.; Tidemand, F.G.; Pedersen, M.C.; Huda, P.; Berndtsson, J.; Darwish, T.; Yepuri, N.R.; et al. Mg2+-Dependent Conformational Equilibria in CorA and an Integrated View on Transport Regulation. eLife 2022, 11, e71887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabel, F. Small-Angle Neutron Scattering for Structural Biology of Protein–RNA Complexes. In Methods in Enzymology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; Volume 558, pp. 391–415. ISBN 978-0-12-801934-4. [Google Scholar]

- Breyton, C.; Gabel, F.; Lethier, M.; Flayhan, A.; Durand, G.; Jault, J.-M.; Juillan-Binard, C.; Imbert, L.; Moulin, M.; Ravaud, S.; et al. Small Angle Neutron Scattering for the Study of Solubilised Membrane Proteins. Eur. Phys. J. E 2013, 36, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiyama, M.; Yagi, H.; Ishii, K.; Porcar, L.; Martel, A.; Oyama, K.; Noda, M.; Yunoki, Y.; Murakami, R.; Inoue, R.; et al. Structural Characterization of the Circadian Clock Protein Complex Composed of KaiB and KaiC by Inverse Contrast-Matching Small-Angle Neutron Scattering. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 35567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapinaite, A.; Carlomagno, T.; Gabel, F. Small-Angle Neutron Scattering of RNA–Protein Complexes. In RNA Spectroscopy; Arluison, V., Wien, F., Eds.; Methods in Molecular Biology; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2020; Volume 2113, pp. 165–188. ISBN 978-1-0716-0277-5. [Google Scholar]

- Combet, S.; Bonneté, F.; Finet, S.; Pozza, A.; Saade, C.; Martel, A.; Koutsioubas, A.; Lacapère, J.-J. Effect of Amphiphilic Environment on the Solution Structure of Mouse TSPO Translocator Protein. Biochimie 2023, 205, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maric, S.; Skar-Gislinge, N.; Midtgaard, S.; Thygesen, M.B.; Schiller, J.; Frielinghaus, H.; Moulin, M.; Haertlein, M.; Forsyth, V.T.; Pomorski, T.G.; et al. Stealth Carriers for Low-Resolution Structure Determination of Membrane Proteins in Solution. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2014, 70, 317–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Josts, I.; Nitsche, J.; Maric, S.; Mertens, H.D.; Moulin, M.; Haertlein, M.; Prevost, S.; Svergun, D.I.; Busch, S.; Forsyth, V.T.; et al. Conformational States of ABC Transporter MsbA in a Lipid Environment Investigated by Small-Angle Scattering Using Stealth Carrier Nanodiscs. Structure 2018, 26, 1072–1079.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johansen, N.T.; Tidemand, F.G.; Nguyen, T.T.T.N.; Rand, K.D.; Pedersen, M.C.; Arleth, L. Circularized and Solubility-enhanced MSP s Facilitate Simple and High-yield Production of Stable Nanodiscs for Studies of Membrane Proteins in Solution. FEBS J. 2019, 286, 1734–1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Ren, Q.; Novick, S.J.; Strutzenberg, T.S.; Griffin, P.R.; Bao, H. One-Step Construction of Circularized Nanodiscs Using SpyCatcher-SpyTag. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 5451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, M.; Huang, Y.; Craigie, R.; Clore, G.M. A Simple Protocol for Expression of Isotope-Labeled Proteins in Escherichia Coli Grown in Shaker Flasks at High Cell Density. J. Biomol. NMR 2019, 73, 743–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bligh, E.G.; Dyer, W.J. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can. J. Biochem. Physiol. 1959, 37, 911–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folch, J.; Lees, M.; Sloane Stanley, G.H. A Simple Method for the Isolation and Purification of Total Lipides from Animal Tissues. J. Biol. Chem. 1957, 226, 497–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakanishi, H.; Hayashida, K.; Nishizawa, T.; Oshima, A.; Abe, K. Cryo-EM of the ATP11C Flippase Reconstituted in Nanodiscs Shows a Distended Phospholipid Bilayer Inner Membrane around Transmembrane Helix 2. J. Biol. Chem. 2022, 298, 101498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tully, M.D.; Kieffer, J.; Brennich, M.E.; Cohen Aberdam, R.; Florial, J.B.; Hutin, S.; Oscarsson, M.; Beteva, A.; Popov, A.; Moussaoui, D.; et al. BioSAXS at European Synchrotron Radiation Facility—Extremely Brilliant Source: BM29 with an Upgraded Source, Detector, Robot, Sample Environment, Data Collection and Analysis Software. J. Synchrotron Rad. 2023, 30, 258–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kieffer, J.; Brennich, M.; Florial, J.-B.; Oscarsson, M.; De Maria Antolinos, A.; Tully, M.; Pernot, P. New Data Analysis for BioSAXS at the ESRF. J. Synchrotron Rad. 2022, 29, 1318–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsen, A.H.; Pedersen, M.C. Experimental Noise in Small-Angle Scattering Can Be Assessed Using the Bayesian Indirect Fourier Transformation. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2021, 54, 1281–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakano, M.; Fukuda, M.; Kudo, T.; Miyazaki, M.; Wada, Y.; Matsuzaki, N.; Endo, H.; Handa, T. Static and Dynamic Properties of Phospholipid Bilayer Nanodiscs. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 8308–8312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, P.; Faraone, A.; Kelley, E.G.; Benedetto, A. Stiffening Effect of the [Bmim][Cl] Ionic Liquid on the Bending Dynamics of DMPC Lipid Vesicles. J. Phys. Chem. B 2021, 125, 7241–7250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, W.T. Small-Angle Neutron Scattering for Studying Lipid Bilayer Membranes. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, R.D.; Bello, G.; Kikhney, A.G.; Torres, J.; Surya, W.; Wölk, C.; Shen, C. Absolute Scattering Length Density Profile of Liposome Bilayers Obtained by SAXS Combined with GIXOS: A Tool to Determine Model Biomembrane Structure. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2023, 56, 1639–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gidden, J.; Denson, J.; Liyanage, R.; Ivey, D.M.; Lay, J.O. Lipid Compositions in Escherichia Coli and Bacillus Subtilis during Growth as Determined by MALDI-TOF and TOF/TOF Mass Spectrometry. Int. J. Mass. Spectrom. 2009, 283, 178–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barák, I.; Muchová, K. The Role of Lipid Domains in Bacterial Cell Processes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 4050–4065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corucci, G.; Vadukul, D.M.; Paracini, N.; Laux, V.; Batchu, K.C.; Aprile, F.A.; Pastore, A. Membrane Charge Drives the Aggregation of TDP-43 Pathological Fragments. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2025, 147, 13577–13591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diomandé, S.E.; Nguyen-The, C.; Guinebretière, M.-H.; Broussolle, V.; Brillard, J. Role of Fatty Acids in Bacillus Environmental Adaptation. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneda, T. Fatty Acids in the Genus Bacillus I. Iso- and Anteiso-Fatty Acids as Characteristic Constituents of Lipids in 10 Species. J. Bacteriol. 1967, 93, 894–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kates, M. Bacterial Lipids. Adv. Lipid Res. 1964, 2, 17–90. [Google Scholar]

- Macfarlane, M.G. Cardiolipin and Other Phospholipids in Ox Liver. Biochem. J. 1961, 78, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barclay, A.; Tidemand Johansen, N.; Tidemand, F.G.; Arleth, L.; Pedersen, M.C. Global Fitting of Multiple Data Frames from SEC–SAXS to Investigate the Structure of next-Generation Nanodiscs. Acta Crystallogr. D Struct. Biol. 2022, 78, 483–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Ghellinck, A.; Schaller, H.; Laux, V.; Haertlein, M.; Sferrazza, M.; Maréchal, E.; Wacklin, H.; Jouhet, J.; Fragneto, G. Production and Analysis of Perdeuterated Lipids from Pichia Pastoris Cells. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e92999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| % D2O | Parameters (Å) | SLD (10−6 Å−2) | Χ2/Pts | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a-Radius | b/a-Radius Factor | c-Rim Thickness | d-Face Thickness | e-Length | Tails | Headgroups | Belt Protein | Solvent | ||||

| SANS | MSP1D1-DMPC | 0 | 34.65 ± 1.18 | 0.99 ± 0.07 | 8.78 ± 0.08 | 8.44 ± 0.53 | 28.94 ± 0.08 | −0.35 ± 0.01 | 1.89 ± 0.07 | 1.91 | −0.55 | 0.89 |

| 20 | 1.86 ± 0.24 | 2.15 | 0.83 | 0.66 | ||||||||

| 40 | 2.41 ± 0.14 | 2.38 | 2.22 | 0.90 | ||||||||

| 60 | 2.78 ± 0.19 | 2.61 | 3.60 | 1.36 | ||||||||

| 80 | 2.73 ± 0.30 | 2.85 | 4.99 | 1.03 | ||||||||

| csE3-DMPC | 0 | 65.13 ± 0.56 | 0.55 ± 0.01 | 9.79 ± 0.26 | 7.24 ± 0.19 | 31.89 ± 0.63 | −0.39 ± 0.02 | 1.22 ± 0.12 | 1.91 | −0.55 | 1.03 | |

| 20 | 1.97 ± 0.15 | 2.15 | 0.83 | 0.94 | ||||||||

| 40 | 1.94 ± 0.10 | 2.38 | 2.22 | 0.98 | ||||||||

| 60 | 2.21 ± 0.16 | 2.61 | 3.60 | 1.09 | ||||||||

| 80 | 2.34 ± 0.24 | 2.85 | 4.99 | 1.35 | ||||||||

| spNW15-DMPC | 0 | 54.13 ± 0.79 | 0.55 ± 0.02 | 8.89 ± 0.22 | 6.74 ± 0.68 | 29.54 ± 0.79 | −0.37 ± 0.02 | 1.21 ± 0.22 | 1.92 | −0.55 | 1.01 | |

| 20 | 1.69 ± 0.3 | 2.17 | 0.83 | 0.86 | ||||||||

| 40 | 1.82 ± 0.12 | 2.41 | 2.22 | 1.05 | ||||||||

| 60 | 1.88 ± 0.14 | 2.66 | 3.60 | 1.38 | ||||||||

| 80 | 1.50 ± 0.22 | 2.91 | 4.99 | 1.52 | ||||||||

| csE3-EcLip | 0 | 57.34 ± 0.90 | 0.47 ± 0.02 | 9.10 ± 0.83 | 7.99 ± 0.69 | 24.77 ± 1.51 | −0.37 ± 0.01 | 2.81 ± 0.17 | 1.91 | −0.55 | 0.95 | |

| 20 | 1.18 ± 0.42 | 2.15 | 0.83 | 0.64 | ||||||||

| 40 | 2.16 ± 0.17 | 2.38 | 2.22 | 0.70 | ||||||||

| 60 | 1.92 ± 0.19 | 2.61 | 3.60 | 0.70 | ||||||||

| 80 | 2.32 ± 0.26 | 2.85 | 4.99 | 1.01 | ||||||||

| csE3-BsLip | 0 | 57.84 ± 0.84 | 0.58 ± 0.02 | 9.50 ± 0.29 | 8.36 ± 0.59 | 26.07 ± 0.94 | −0.39 ± 0.01 | 1.99 ± 0.05 | 1.91 | −0.55 | 0.71 | |

| 20 | 1.52 ± 0.30 | 2.15 | 0.83 | 0.66 | ||||||||

| 40 | 2.02 ± 0.03 | 2.38 | 2.22 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 60 | 2.19 ± 0.06 | 2.61 | 3.60 | 1.14 | ||||||||

| 80 | 2.99 ± 0.09 | 2.85 | 4.99 | 0.84 | ||||||||

| SAXS | MSP1D1-DMPC | 39.26 ± 2.09 | 0.99 ± 0.00 | 8.99 ± 0.57 | 8.32 ± 0.41 | 30.86 ± 1.00 | 8.25 ± 0.08 | 12.27 ± 0.21 | 11.64 ± 0.05 | 9.40 | 1.27 | |

| csE3-DMPC | 68.52 ± 2.33 | 0.58 ± 0.07 | 8.56 ± 0.67 | 12.51 ± 0.29 | 1.82 | |||||||

| spNW15-DMPC | 58.61 ± 4.69 | 0.55 ± 0.09 | 9.54 ± 0.77 | 11.73 ± 0.04 | 3.86 | |||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Batchu, K.C.; Tully, M.D.; Martel, A. Toward Nanodisc Tailoring for SANS Study of Membrane Proteins. Bioengineering 2026, 13, 87. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering13010087

Batchu KC, Tully MD, Martel A. Toward Nanodisc Tailoring for SANS Study of Membrane Proteins. Bioengineering. 2026; 13(1):87. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering13010087

Chicago/Turabian StyleBatchu, Krishna Chaithanya, Mark D. Tully, and Anne Martel. 2026. "Toward Nanodisc Tailoring for SANS Study of Membrane Proteins" Bioengineering 13, no. 1: 87. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering13010087

APA StyleBatchu, K. C., Tully, M. D., & Martel, A. (2026). Toward Nanodisc Tailoring for SANS Study of Membrane Proteins. Bioengineering, 13(1), 87. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering13010087