Neuromuscular and Kinetic Adaptations to Symmetric and Asymmetric Load Carriage During Walking in Individuals with Chronic Low Back Pain

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Experimental Protocol

2.4. Surface Electromyography

2.5. Data Processing

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Ground Reaction Forces and Load Configuration Effects

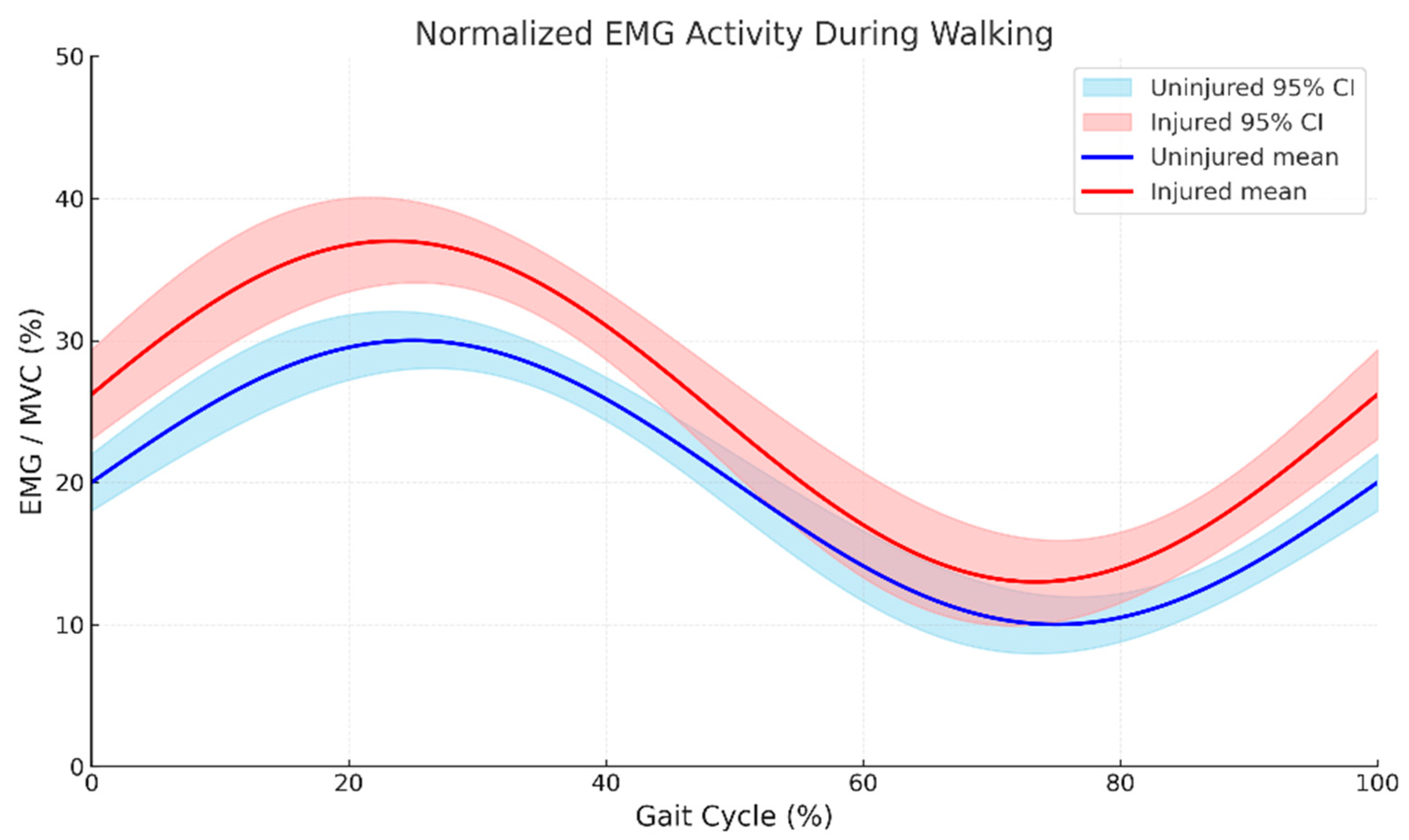

3.2. Trunk Muscle Activation Patterns During Loaded Gait

3.3. Muscle Activation–Length Relationship Alterations

3.4. Left-Side Trunk Muscle Activation Under Variable Loading

3.5. Right-Side Trunk Muscle Activation Under Variable Loading

3.6. Comparative Activation Across Loading Conditions

4. Discussion

Practical Recommendations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wu, A.; March, L.; Zheng, X.; Huang, J.; Wang, X.; Zhao, J.; Blyth, F.M.; Smith, E.; Buchbinder, R.; Hoy, D. Global low back pain prevalence and years lived with disability from 1990 to 2017: Estimates from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Ann. Transl. Med. 2020, 8, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartvigsen, J.; Hancock, M.J.; Kongsted, A.; Louw, Q.; Ferreira, M.L.; Genevay, S.; Hoy, D.; Karppinen, J.; Pransky, G.; Sieper, J.; et al. What low back pain is and why we need to pay attention. Lancet 2018, 391, 2356–2367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoy, D.; March, L.; Brooks, P.; Blyth, F.; Woolf, A.; Bain, C.; Williams, G.; Smith, E.; Vos, T.; Barendregt, J.; et al. The global burden of low back pain: Estimates from the Global Burden of Disease 2010 study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2014, 73, 968–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghafouri, M.; Teymourzadeh, A.; Nakhostin-Ansari, A.; Sepanlou, S.G.; Dalvand, S.; Moradpour, F.; Bavarsad, A.H.; Boogar, S.S.; Dehghan, M.; Ostadrahimi, A.; et al. Prevalence and predictors of low back pain among the Iranian population: Results from the Persian cohort study. Ann. Med. Surg. 2022, 74, 103243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodges, P.W.; Coppieters, M.W.; MacDonald, D.; Cholewicki, J. New insight into motor adaptation to pain revealed by a combination of modelling and empirical approaches. Eur. J. Pain. 2013, 17, 1138–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodges, P.W.; Tucker, K. Moving differently in pain: A new theory to explain the adaptation to pain. Pain 2011, 152, S90–S98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moseley, G.L.; Hodges, P.W. Are the changes in postural control associated with low back pain caused by pain interference? Clin. J. Pain 2005, 21, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Dieën, J.H.; Reeves, N.P.; Kawchuk, G.; van Dillen, L.R.; Hodges, P.W. Motor Control Changes in Low Back Pain: Divergence in Presentations and Mechanisms. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2019, 49, 370–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.H.; Fell, D.W.; Kim, K. Plantar pressure distribution during walking: Comparison of subjects with and without chronic low back pain. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2011, 23, 923–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menz, H.B. Foot Problems in Older People: Assessment and Management; Elsevier Health Sciences: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.-H.; Tsai, W.-C.; Chang, C.-Y.; Hung, M.-H.; Tu, J.-H.; Wu, T.; Chen, C.-H. Effect of Load Carriage Lifestyle on Kinematics and Kinetics of Gait. Appl. Bionics Biomech. 2023, 2023, 8022635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaya Mira, N.; Gómez Hernández, L.M.; Viloria Barragán, C.; Monsalve Montes, M.; Soto Cardona, I.C. Biomechanical and Kinematic Gait Analysis in Lower Limb Amputees: Cross-Sectional Study. JMIR Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2025, 12, e67022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birrell, S.A.; Haslam, R.A. The effect of military load carriage on 3-D lower limb kinematics and spatiotemporal parameters. Ergonomics 2009, 52, 1298–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LaFiandra, M.; Wagenaar, R.C.; Holt, K.G.; Obusek, J.P. How do load carriage and walking speed influence trunk coordination and stride parameters? J. Biomech. 2003, 36, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marino, G.; Scano, A.; Beltrame, G.; Brambilla, C.; Marazzi, A.; Aparo, F.; Molinari Tosatti, L.; Gatti, R.; Portinaro, N. Influence of Backpack Carriage and Walking Speed on Muscle Synergies in Healthy Children. Bioengineering 2024, 11, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Granata, K.P.; England, S.A. Stability of dynamic trunk movement. Spine 2006, 31, E271–E276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liew, B.X.W.; Del Vecchio, A.; Falla, D. The influence of musculoskeletal pain disorders on muscle synergies-A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0206885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dieën, J.H.; Selen, L.P.; Cholewicki, J. Trunk muscle activation in low-back pain patients, an analysis of the literature. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2003, 13, 333–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laird, R.A.; Keating, J.L.; Kent, P. Subgroups of lumbo-pelvic flexion kinematics are present in people with and without persistent low back pain. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2018, 19, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, J.; Burnfield, J. Gait Analysis: Normal and Pathological Function; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Burden, A. How should we normalize electromyograms obtained from healthy participants? What we have learned from over 25 years of research. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2010, 20, 1023–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakdash, J.Z.; Marusich, L.R. Repeated Measures Correlation. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairbank, J.C.; Pynsent, P.B. The Oswestry Disability Index. Spine 2000, 25, 2940–2952; discussion 2952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.G.; Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakens, D. Sample size justification. Collabra Psychol. 2022, 8, 33267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seay, J.F.; Van Emmerik, R.E.; Hamill, J. Low back pain status affects pelvis-trunk coordination and variability during walking and running. Clin. Biomech. 2011, 26, 572–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera-Garcia, F.J.; Moreside, J.M.; McGill, S.M. MVC techniques to normalize trunk muscle EMG in healthy women. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2010, 20, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Besier, T.F.; Fredericson, M.; Gold, G.E.; Beaupré, G.S.; Delp, S.L. Knee muscle forces during walking and running in patellofemoral pain patients and pain-free controls. J. Biomech. 2009, 42, 898–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeni, J.A., Jr.; Richards, J.G.; Higginson, J.S. Two simple methods for determining gait events during treadmill and overground walking using kinematic data. Gait Posture 2008, 27, 710–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merletti, R.; Hermens, H. Introduction to the special issue on the SENIAM European Concerted Action. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2000, 10, 283–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermens, H.J.; Freriks, B.; Disselhorst-Klug, C.; Rau, G. Development of recommendations for SEMG sensors and sensor placement procedures. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2000, 10, 361–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbero, M.; Merletti, R.; Rainoldi, A. Atlas of Muscle Innervation Zones: Understanding Surface Electromyography and Its Applications; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lehman, G.J.; McGill, S.M. The importance of normalization in the interpretation of surface electromyography: A proof of principle. J. Manipulative Physiol. Ther. 1999, 22, 444–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dankaerts, W.; O’Sullivan, P.; Burnett, A.; Straker, L. Differences in sitting postures are associated with nonspecific chronic low back pain disorders when patients are subclassified. Spine 2006, 31, 698–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farì, G.; Megna, M.; Fiore, P.; Ranieri, M.; Marvulli, R.; Bonavolontà, V.; Bianchi, F.P.; Puntillo, F.; Varrassi, G.; Reis, V.M. Real-Time Muscle Activity and Joint Range of Motion Monitor to Improve Shoulder Pain Rehabilitation in Wheelchair Basketball Players: A Non-Randomized Clinical Study. Clin. Pract. 2022, 12, 1092–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reaz, M.B.I.; Hussain, M.S.; Mohd-Yasin, F. Techniques of EMG signal analysis: Detection, processing, classification and applications. Biol. Proced. Online 2006, 8, 11–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodges, P.W.; Bui, B.H. A comparison of computer-based methods for the determination of onset of muscle contraction using electromyography. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1996, 101, 511–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granata, K.P.; Marras, W.S. Cost-benefit of muscle cocontraction in protecting against spinal instability. Spine 2000, 25, 1398–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H. Data analysis. In ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 189–201. [Google Scholar]

- Field, A.; Field, Z.; Miles, J. Discovering Statistics Using R; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Proske, U.; Gandevia, S.C. The proprioceptive senses: Their roles in signaling body shape, body position and movement, and muscle force. Physiol. Rev. 2012, 92, 1651–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, D.; Moseley, L.G.; Hodges, P.W. Why do some patients keep hurting their back? Evidence of ongoing back muscle dysfunction during remission from recurrent back pain. Pain 2009, 142, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavcic, N.; Grenier, S.; McGill, S.M. Determining the stabilizing role of individual torso muscles during rehabilitation exercises. Spine 2004, 29, 1254–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callaghan, J.P.; Patla, A.E.; McGill, S.M. Low back three-dimensional joint forces, kinematics, and kinetics during walking. Clin. Biomech. 1999, 14, 203–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, J.D.; Abboud, J.; St-Pierre, C.; Piché, M.; Descarreaux, M. Neuromuscular adaptations predict functional disability independently of clinical pain and psychological factors in patients with chronic non-specific low back pain. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2014, 24, 550–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Zuriaga, D.; López-Pascual, J.; Garrido-Jaén, D.; de Moya, M.F.; Prat-Pastor, J. Reliability and validity of a new objective tool for low back pain functional assessment. Spine 2011, 36, 1279–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massé-Alarie, H.; Beaulieu, L.D.; Preuss, R.; Schneider, C. The side of chronic low back pain matters: Evidence from the primary motor cortex excitability and the postural adjustments of multifidi muscles. Exp. Brain Res. 2017, 235, 647–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schabrun, S.M.; Elgueta-Cancino, E.L.; Hodges, P.W. Smudging of the Motor Cortex Is Related to the Severity of Low Back Pain. Spine 2017, 42, 1172–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.E.; Littlewood, C.; May, S. An update of stabilisation exercises for low back pain: A systematic review with meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2014, 15, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strutton, P.H.; Theodorou, S.; Catley, M.; McGregor, A.H.; Davey, N.J. Corticospinal excitability in patients with chronic low back pain. J. Spinal Disord. Tech. 2005, 18, 420–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Sullivan, K.; O’Keeffe, M.; Forster, B.B.; Qamar, S.R.; van der Westhuizen, A.; O’Sullivan, P.B. Managing low back pain in active adolescents. Best. Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 2019, 33, 102–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russo, M.; Deckers, K.; Eldabe, S.; Kiesel, K.; Gilligan, C.; Vieceli, J.; Crosby, P. Muscle Control and Non-specific Chronic Low Back Pain. Neuromodulation 2018, 21, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortin, M.; Dobrescu, O.; Courtemanche, M.; Sparrey, C.J.; Santaguida, C.; Fehlings, M.G.; Weber, M.H. Association Between Paraspinal Muscle Morphology, Clinical Symptoms, and Functional Status in Patients With Degenerative Cervical Myelopathy. Spine 2017, 42, 232–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hug, F.; Del Vecchio, A.; Avrillon, S.; Farina, D.; Tucker, K. Muscles from the same muscle group do not necessarily share common drive: Evidence from the human triceps surae. J. Appl. Physiol. 2021, 130, 342–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larivière, C.; Arsenault, A.B.; Gravel, D.; Gagnon, D.; Loisel, P. Evaluation of measurement strategies to increase the reliability of EMG indices to assess back muscle fatigue and recovery. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2002, 12, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Muscle | CLBP Group | Control Group | Statistical Effects (p-Value) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Load | As 10% | S 10% | As 20% | S 20% | No Load | As 10% | S 10% | As 20% | S 20% | G | P | LC | G×P×LC | |

| LEO | 0.126 d | 0.187 b | 0.154 c | 0.243 a | 0.216 a | 0.100 d | 0.172 b | 0.144 c | 0.214 a | 0.190 b | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.059 |

| LIO | 0.125 c | 0.188 b | 0.161 b | 0.237 a | 0.222 a | 0.094 | 0.173 b | 0.134 c | 0.220 a | 0.187 a | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.052 |

| LLD | 0.100 c | 0.174 b | 0.134 c | 0.215 a | 0.188 a | 0.075 | 0.152 bc | 0.117 c | 0.195 a | 0.175 b | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.136 |

| LLE | 0.154 c | 0.230 a | 0.201 b | 0.282 a | 0.256 a | 0.140 c | 0.220 ab | 0.183 b | 0.262 a | 0.230 a | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.451 |

| LM | 0.143 c | 0.219 ab | 0.177 b | 0.263 a | 0.225 a | 0.121 c | 0.192 b | 0.158 bc | 0.239 a | 0.211 ab | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.595 |

| LRA | 0.120 c | 0.193 b | 0.161 b | 0.240 a | 0.211 a | 0.099 | 0.171 b | 0.136 c | 0.222 a | 0.187 b | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.883 |

| LTF | 0.125 c | 0.186 b | 0.156 bc | 0.244 a | 0.206 a | 0.095 c | 0.169 b | 0.137 c | 0.210 a | 0.185 b | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.114 |

| Muscle | CLBP Group | Control Group | Statistical Effects (p-Value) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Load | As 10% | S 10% | As 20% | S 20% | No Load | As 10% | S 10% | As 20% | S 20% | G | P | LC | G×P×LC | |

| REO | 0.129 e | 0.197 bc | 0.158 d | 0.236 a | 0.214 b | 0.104 e | 0.170 c | 0.132 d | 0.212 b | 0.189 bc | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.156 |

| RIO | 0.122 e | 0.186 bc | 0.163 d | 0.231 a | 0.210 b | 0.097 e | 0.173 c | 0.140 d | 0.213 b | 0.196 bc | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.351 |

| RLD | 0.097 e | 0.169 bc | 0.142 d | 0.220 a | 0.193 b | 0.079 e | 0.145 c | 0.117 d | 0.190 b | 0.169 bc | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.647 |

| RLE | 0.167 e | 0.227 b | 0.199 cd | 0.276 a | 0.253 a | 0.142 d | 0.210 b | 0.184 c | 0.258 b | 0.236 b | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.460 |

| RM | 0.139 de | 0.215 bc | 0.181 c | 0.260 a | 0.231 b | 0.125 e | 0.196 c | 0.158 d | 0.243 b | 0.212 bc | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.835 |

| RRA | 0.119 e | 0.191 bc | 0.165 d | 0.239 a | 0.212 b | 0.097 e | 0.172 c | 0.144 d | 0.215 b | 0.197 bc | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.434 |

| RTF | 0.122 e | 0.187 bc | 0.122 e | 0.239 a | 0.159 c | 0.105 e | 0.175 c | 0.146 d | 0.213 b | 0.190 bc | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.463 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Tajik, R.; Dhahbi, W.; Mimar, R.; Khaleghi Tazji, M.; Ceylan, H.İ.; Bayrakdaroğlu, S.; Stefanica, V.; Hammami, N. Neuromuscular and Kinetic Adaptations to Symmetric and Asymmetric Load Carriage During Walking in Individuals with Chronic Low Back Pain. Bioengineering 2026, 13, 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering13010082

Tajik R, Dhahbi W, Mimar R, Khaleghi Tazji M, Ceylan Hİ, Bayrakdaroğlu S, Stefanica V, Hammami N. Neuromuscular and Kinetic Adaptations to Symmetric and Asymmetric Load Carriage During Walking in Individuals with Chronic Low Back Pain. Bioengineering. 2026; 13(1):82. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering13010082

Chicago/Turabian StyleTajik, Raheleh, Wissem Dhahbi, Raghad Mimar, Mehdi Khaleghi Tazji, Halil İbrahim Ceylan, Serdar Bayrakdaroğlu, Valentina Stefanica, and Nadhir Hammami. 2026. "Neuromuscular and Kinetic Adaptations to Symmetric and Asymmetric Load Carriage During Walking in Individuals with Chronic Low Back Pain" Bioengineering 13, no. 1: 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering13010082

APA StyleTajik, R., Dhahbi, W., Mimar, R., Khaleghi Tazji, M., Ceylan, H. İ., Bayrakdaroğlu, S., Stefanica, V., & Hammami, N. (2026). Neuromuscular and Kinetic Adaptations to Symmetric and Asymmetric Load Carriage During Walking in Individuals with Chronic Low Back Pain. Bioengineering, 13(1), 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering13010082