From Production to the Clinic: Decellularized Extracellular Matrix as a Biomaterial for Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Production of Decellularized Extracellular Matrix

2.1. Physical Methods

2.2. Chemical Methods

2.3. Biological Methods

3. Characterization of Decellularized Extracellular Matrix

4. Decellularized Extracellular-Matrix-Related Patents

4.1. Evolution of Decellularization Technology Patents

4.2. Novel Decellularization Technology Patents

4.3. Tissue/Organ-Specific Decellularized ECM Patents

4.4. Challenges in Patent Translation to Commercial Products

5. Clinical Application of Decellularized Biomaterials

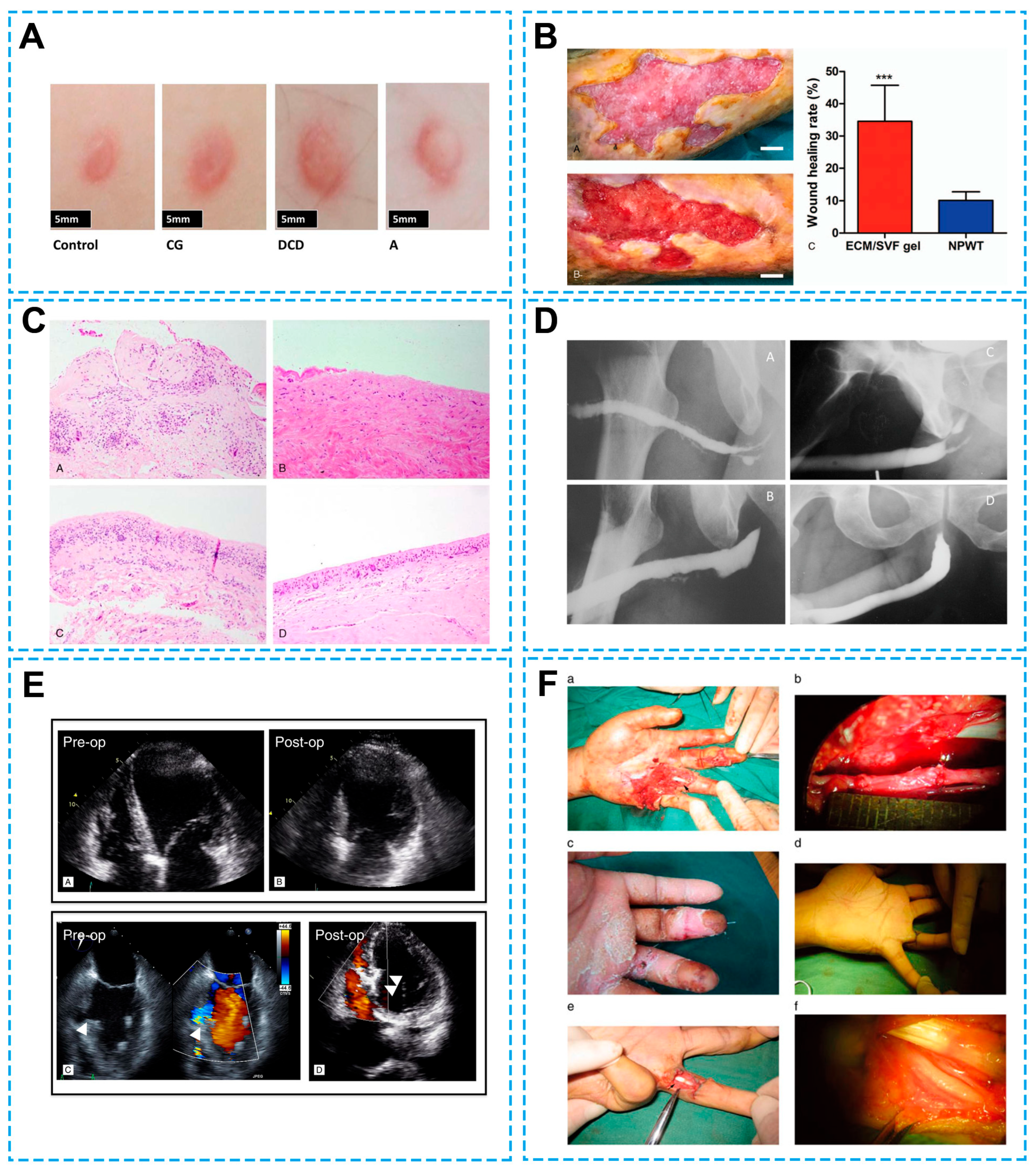

5.1. Skin Wound Healing

5.2. Urogenital System Repair

5.3. Cardiovascular System Repair

5.4. Nerve Defect Repair

6. Challenges and Future Prospects

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DAPI | 4,6-Diamino-2-phenylindole |

| dECM | Decellularized extracellular matrix |

| ECM | Extracellular matrix |

References

- Li, Y.Y.; Wu, J.W.; Ye, P.L.; Cai, Y.L.; Shao, M.F.; Zhang, T.; Guo, Y.C.; Zeng, S.J.; Pathak, J.L. Decellularized Extracellular Matrix Scaffolds: Recent Advances and Emerging Strategies in Bone Tissue Engineering. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2024, 10, 7372–7385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangani, S.; Vetoulas, M.; Mineschou, K.; Spanopoulos, K.; Vivanco, M.D.; Piperigkou, Z.; Karamanos, N.K. Design and Applications of Extracellular Matrix Scaffolds in Tissue Engineering and Regeneration. Cells 2025, 14, 1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Kampen, K.A.; Mota, C.; Moroni, L. A Tissue Engineering’s Guide to Biomimicry. Macromol. Biosci. 2025, 25, e00093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N.S.; Karan, A.; Tran, H.Q.; John, J.; Andrabi, S.M.; Shahriar, S.M.S.; Xie, J.W. Decellularized Extracellular Matrix-Decorated 3D Nanofiber Scaffolds Enhance Cellular Responses and Tissue Regeneration. Acta Biomater. 2024, 184, 81–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milan, P.B.; Masoumi, F.; Biazar, E.; Jalise, S.Z.; Mehrabi, A. Exploiting the Potential of Decellularized Extracellular Matrix (ECM) in Tissue Engineering: A Review Study. Macromol. Biosci. 2025, 25, e2400322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golebiowska, A.A.; Intravaia, J.T.; Sathe, V.M.; Kumbar, S.G.; Nukavarapu, S.P. Decellularized Extracellular Matrix Biomaterials for Regenerative Therapies: Advances, Challenges and Clinical Prospects. Bioact. Mater. 2024, 32, 98–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neishabouri, A.; Khaboushan, A.S.; Daghigh, F.; Kajbafzadeh, A.M.; Zolbin, M.M. Decellularization in Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine: Evaluation, Modification, and Application Methods. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 805299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Tang, Q.L.; Yang, Q.; Li, M.M.; Zeng, S.Y.; Yang, X.M.; Xiao, Z.; Tong, X.Y.; Lei, L.J.; Li, S.S. Functional Acellular Matrix for Tissue Repair. Mater. Today Bio 2023, 18, 100530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brigido, S.A. The Use of an Acellular Dermal Regenerative Tissue Matrix in the Treatment of Lower Extremity Wounds: A Prospective 16-Week Pilot Study. Int. Wound J. 2006, 3, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Headon, H.; Kasem, A.; Manson, A.; Choy, C.; Carmichael, A.R.; Mokbel, K. Clinical Outcome and Patient Satisfaction with the Use of Bovine-Derived Acellular Dermal Matrix (Surgimend™) in Implant Based Immediate Reconstruction Following Skin Sparing Mastectomy: A Prospective Observational Study in a Single Centre. Surg. Oncol. 2016, 25, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Eredità, R. Porcine Small Intestinal Submucosa (SIS) Myringoplasty in Children: A Randomized Controlled Study. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2015, 79, 1085–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, B.; Zhu, Q.T.; Chai, Y.M.; Ding, X.H.; Tang, J.Y.; Gu, L.Q.; Xiang, J.P.; Yang, Y.X.; Zhu, J.K.; Liu, X.L. Safety and Efficacy Evaluation of a Human Acellular Nerve Graft as a Digital Nerve Scaffold: A Prospective, Multicentre Controlled Clinical Trial. J. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2015, 9, 286–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sackett, S.D.; Tremmel, D.M.; Ma, F.F.; Feeney, A.K.; Maguire, R.M.; Brown, M.E.; Zhou, Y.; Li, X.; O’Brien, C.; Li, L.J.; et al. Extracellular Matrix Scaffold and Hydrogel Derived from Decellularized and Delipidized Human Pancreas. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 10452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, H.X.; Hoshiba, T.; Kawazoe, N.; Koda, I.; Song, M.H.; Chen, G.P. Cultured Cell-Derived Extracellular Matrix Scaffolds for Tissue Engineering. Biomaterials 2011, 32, 9658–9666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.J.; Cho, J.Y.; Heo, T.H.; Yang, D.H.; Chun, H.J.; Yoon, J.K.; Jeong, G.J. Recent Advances in Applications of Nanoparticles and Decellularized ECM for Organoid Engineering. Mater. Today Bio 2025, 35, 102274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.X.; Liu, X.B.; Ahmad, M.A.; Ao, Q.; Yu, Y.; Shao, D.; Yu, T.H. Engineering Cell-Derived Extracellular Matrix for Peripheral Nerve Regeneration. Mater. Today Bio 2024, 27, 101125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aamodt, J.M.; Grainger, D.W. Extracellular Matrix-Based Biomaterial Scaffolds and the Host Response. Biomaterials 2016, 86, 68–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, K.H.; Choi, B.H.; Park, S.R.; Kim, B.J.; Min, B.H. The Chondrogenic Differentiation of Mesenchymal Stem Cells on an Extracellular Matrix Scaffold Derived from Porcine Chondrocytes. Biomaterials 2010, 31, 5355–5365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolchok, J.C.; Tresco, P.A. The Isolation of Cell Derived Extracellular Matrix Constructs Using Sacrificial Open-Cell Foams. Biomaterials 2010, 31, 9595–9603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volpato, F.Z.; Führmann, T.; Migliaresi, C.; Hutmacher, D.W.; Dalton, P.D. Using Extracellular Matrix for Regenerative Medicine in the Spinal Cord. Biomaterials 2013, 34, 4945–4955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, L.; Jiang, C.Y.; Yu, B.; Zhu, J.W.; Sun, Y.Y.; Yi, S. Single-Cell Profiling of Cellular Changes in the Somatic Peripheral Nerves Following Nerve Injury. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1448253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Xie, J.L.; Dai, W.Y.; Lu, B.; Yi, S. Schwann Cells in Regeneration and Cancer. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1506552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, Y.; Zhu, J.B.; Xue, C.B.; Li, Z.M.Y.; Ding, F.; Yang, Y.M.; Gu, X.S. Chitosan/Silk Fibroin-Based, Schwann Cell-Derived Extracellular Matrix-Modified Scaffolds for Bridging Rat Sciatic Nerve Gaps. Biomaterials 2014, 35, 2253–2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.R.; Zhu, C.L.; Zhang, B.; Hu, J.X.; Xu, J.H.; Xue, C.B.; Bao, S.X.; Gu, X.K.; Ding, F.; Yang, Y.M.; et al. BMSC-Derived Extracellular Matrix Better Optimizes the Microenvironment to Support Nerve Regeneration. Biomaterials 2022, 280, 121251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.L.; Huang, J.; Xue, C.B.; Wang, Y.X.; Wang, S.R.; Bao, S.X.; Chen, R.Y.; Li, Y.; Gu, Y. Skin Derived Precursor Schwann Cell-Generated Acellular Matrix Modified Chitosan/Silk Scaffolds for Bridging Rat Sciatic Nerve Gap. Neurosci. Res. 2018, 135, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, D.; Zreiqat, H.; Benkirane-Jessel, N.; Ramakrishna, S.; Ramalingam, M. Development of Decellularized Scaffolds for Stem Cell-Driven Tissue Engineering. J. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2017, 11, 942–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crapo, P.M.; Gilbert, T.W.; Badylak, S.F. An Overview of Tissue and Whole Organ Decellularization Processes. Biomaterials 2011, 32, 3233–3243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagata, S.; Hanayama, R.; Kawane, K. Autoimmunity and the Clearance of Dead Cells. Cell 2010, 140, 619–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulver; Sheytsov, A.; Leybovich, B.; Artyuhov, I.; Maleev, Y.; Peregudov, A. Production of Organ Extracellular Matrix Using a Freeze-Thaw Cycle Employing Extracellular Cryoprotectants. Cryoletters 2014, 35, 400–406. [Google Scholar]

- Mosala Nezhad, Z.; Poncelet, A.; de Kerchove, L.; Gianello, P.; Fervaille, C.; El Khoury, G. Small Intestinal Submucosa Extracellular Matrix (CorMatrix®) in Cardiovascular Surgery: A Systematic Review. Interdiscip. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg. 2016, 22, 839–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabetkish, S.; Kajbafzadeh, A.M.; Sabetkish, N.; Khorramirouz, R.; Akbarzadeh, A.; Seyedian, S.L.; Pasalar, P.; Orangian, S.; Beigi, R.S.H.; Aryan, Z.; et al. Whole-Organ Tissue Engineering: Decellularization and Recellularization of Three-Dimensional Matrix Liver Scaffolds. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 2015, 103, 1498–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koo, M.A.; Jeong, H.; Hong, S.H.; Seon, G.M.; Lee, M.H.; Park, J.C. Preconditioning Process for Dermal Tissue Decellularization Using Electroporation with Sonication. Regen. Biomater. 2022, 9, rbab071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, S.; Lu, F.; Chen, L.; Li, C.; Zhou, X.; Wu, Y.; Chen, H.; Yan, G.; Qi, Z. Preparation of a Decellularized Scaffold from Hare Carotid Artery for Vascular Tissue Engineering Applications. Tissue Eng. Part A 2015, 21, S231. [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki, S.; Funamoto, S.; Hashimoto, Y.; Kimura, T.; Honda, T.; Hattori, S.; Kobayashi, H.; Kishida, A.; Mochizuki, M. In Vivo Evaluation of a Novel Scaffold for Artificial Corneas Prepared by Using Ultrahigh Hydrostatic Pressure to Decellularize Porcine Corneas. Mol. Vis. 2009, 15, 2022–2028. [Google Scholar]

- Funamoto, S.; Nam, K.; Kimura, T.; Murakoshi, A.; Hashimoto, Y.; Niwaya, K.; Kitamura, S.; Fujisato, T.; Kishida, A. The Use of High-Hydrostatic Pressure Treatment to Decellularize Blood Vessels. Biomaterials 2010, 31, 3590–3595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoya, C.V.; McFetridge, P.S. Preparation of Ex Vivo-Based Biomaterials Using Convective Flow Decellularization. Tissue Eng. Part C Methods 2009, 15, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierad, L.N.; Shaw, E.L.; Bina, A.; Brazile, B.; Rierson, N.; Patnaik, S.S.; Kennamer, A.; Odum, R.; Cotoi, O.; Terezia, P.; et al. Functional Heart Valve Scaffolds Obtained by Complete Decellularization of Porcine Aortic Roots in a Novel Differential Pressure Gradient Perfusion System. Tissue Eng. Part C Methods 2015, 21, 1284–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keane, T.J.; Swinehart, I.T.; Badylak, S.F. Methods of Tissue Decellularization used for Preparation of Biologic Scaffolds and Relevance. Methods 2015, 84, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.H.; Tseng, F.W.; Chang, W.H.; Peng, I.C.; Hsieh, D.J.; Wu, S.W.; Yeh, M.L. Preparation of Acellular Scaffold for Corneal Tissue Engineering by Supercritical Carbon Dioxide Extraction Technology. Acta Biomater. 2017, 58, 238–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guler, S.; Aslan, B.; Hosseinian, P.; Aydin, H.M. Supercritical Carbon Dioxide-Assisted Decellularization of Aorta and Cornea. Tissue Eng. Part C Methods 2017, 23, 540–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiemer, B.; Genz, B.; Jonitz-Heincke, A.; Pasold, J.; Wree, A.; Dommerich, S.; Bader, R. Devitalisation of Human Cartilage by High Hydrostatic Pressure Treatment: Subsequent Cultivation of Chondrocytes and Mesenchymal Stem Cells on the Devitalised Tissue. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 33747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jungebluth, P.; Go, T.; Asnaghi, A.; Bellini, S.; Martorell, J.; Calore, C.; Urbani, L.; Ostertag, H.; Mantero, S.; Conconi, M.T.; et al. Structural and Morphologic Evaluation of a Novel Detergent-Enzymatic Tissue-Engineered Tracheal Tubular Matrix. J. Thorac. Cardiov. Sur. 2009, 138, 586–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.C.; Wei, X.F.; Yi, W.; Gu, C.H.; Kang, X.J.; Liu, Y.; Li, Q.; Yi, D.H. RGD-Modified Acellular Bovine Pericardium as a Bioprosthetic Scaffold for Tissue Engineering. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2009, 20, 2327–2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisbig, N.A.; Hussein, H.A.; Pinnell, E.; Bertone, A.L. Comparison of Four Methods for Generating Decellularized Equine Synovial Extracellular Matrix. Am. J. Vet. Res. 2016, 77, 1332–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawecki, M.; Labus, W.; Klama-Baryla, A.; Kitala, D.; Kraut, M.; Glik, J.; Misiuga, M.; Nowak, M.; Bielecki, T.; Kasperczyk, A. A Review of Decellurization Methods Caused by an Urgent Need for Quality Control of Cell-Free Extracellular Matrix’ Scaffolds and Their Role in Regenerative Medicine. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B 2018, 106, 909–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reing, J.E.; Brown, B.N.; Daly, K.A.; Freund, J.M.; Gilbert, T.W.; Hsiong, S.X.; Huber, A.; Kullas, K.E.; Tottey, S.; Wolf, M.T.; et al. The Effects of Processing Methods upon Mechanical and Biologic Properties of Porcine Dermal Extracellular Matrix Scaffolds. Biomaterials 2010, 31, 8626–8633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza-Novelo, B.; Avila, E.E.; Cauich-Rodríguez, J.V.; Jorge-Herrero, E.; Rojo, F.J.; Guinea, G.V.; Mata-Mata, J.L. Decellularization of Pericardial Tissue and Its Impact on Tensile Viscoelasticity and Glycosaminoglycan Content. Acta Biomater. 2011, 7, 1241–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varhac, R.; Robinson, N.C.; Musatov, A. Removal of Bound Triton X-100 from Purified Bovine Heart Cytochrome. Anal. Biochem. 2009, 395, 268–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Li, Z.N.; Yu, T.H.; Wang, W.Z.; Tao, M.H.; Wang, S.L.; Ma, Y.Z.; Fan, J.; Tian, X.H.; Wang, X.H.; et al. In Vitro and In Vivo Biocompatibility Study on Acellular Sheep Periosteum for Guided Bone Regeneration. Biomed. Mater. 2020, 15, 015013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, J.; Joyce, E.M.; Sacks, M.S. Effects of Decellularization on the Mechanical and Structural Properties of The Porcine Aortic Valve Leaflet. Biomaterials 2008, 29, 1065–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faulk, D.M.; Carruthers, C.A.; Warner, H.J.; Kramer, C.R.; Reing, J.E.; Zhang, L.; D’Amore, A.; Badylak, S.F. The Effect of Detergents on the Basement Membrane Complex of a Biologic Scaffold Material. Acta Biomater. 2014, 10, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.M.; Li, Y.; Mo, X.M. The Study of a New Detergent (Octyl-Glucopyranoside) for Decellularizing Porcine Pericardium as Tissue Engineering Scaffold. J. Surg. Res. 2013, 183, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bera, A.K.; Sriya, Y.; Pati, F. Formulation of Dermal Tissue Matrix Bioink by a Facile Decellularization Method and Process Optimization for 3D Bioprinting toward Translation Research. Macromol. Biosci. 2022, 22, 2200109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumpkins, S.B.; Pierre, N.; McFetridge, P.S. A Mechanical Evaluation of Three Decellularization Methods in the Design of a Xenogeneic Scaffold for Tissue Engineering the Temporomandibular Joint Disc. Acta Biomater. 2008, 4, 808–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopera, H.M.; Griffiths, L.G. Antigen Removal Process Preserves Function of Small Diameter Venous valved conduits, Whereas SDS-Decellularization Results in Significant Valvular Insufficiency. Acta Biomater. 2020, 107, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bongolan, T.; Whiteley, J.; Castillo-Prado, J.; Fantin, A.; Larsen, B.; Wong, C.J.; Mazilescu, L.; Kawamura, M.; Urbanellis, P.; Jonebring, A.; et al. Decellularization of Porcine Kidney with Submicellar Concentrations of SDS Results in the Retention of ECM Proteins Required for the Adhesion and Maintenance of Human Adult Renal Epithelial Cells. Biomater. Sci. 2022, 10, 2972–2990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakayama, K.H.; Batchelder, C.A.; Lee, C.I.; Tarantal, A.F. Decellularized Rhesus Monkey Kidney as a Three-Dimensional Scaffold for Renal Tissue Engineering. Tissue. Eng. Part A 2010, 16, 2207–2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woods, T.; Gratzer, P.F. Effectiveness of Three Extraction Techniques in the Development of a Decellularized Bone-Anterior Cruciate Ligament-Bone Graft. Biomaterials 2005, 26, 7339–7349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahl, S.L.M.; Koh, J.; Prabhakar, V.; Niklason, L.E. Decellularized Native and Engineered Arterial Scaffolds for Transplantation. Cell Transplant 2003, 12, 659–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.N.; Ho, H.O.; Tsai, Y.T.; Sheu, M.T. Process Development of an Acellular Dermal Matrix (ADM) for Biomedical Applications. Biomaterials 2004, 25, 2679–2686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.W.; Solorio, L.D.; Alsberg, E. Decellularized Tissue and Cell-Derived Extracellular Matrices as Scaffolds for Orthopaedic Tissue Engineering. Biotechnol. Adv. 2014, 32, 462–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.; Griffin, M.; Naik, A.; Szarko, M.; Butler, P.E.M. Optimising the Decellularization of Human Elastic Cartilage with Trypsin for Future Use in Ear Reconstruction. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 3097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hensley, A.; Rames, J.; Casler, V.; Rood, C.; Walters, J.; Fernandez, C.; Gill, S.; Mercuri, J.J. Decellularization and Characterization of a Whole Intervertebral Disk Xenograft Scaffold. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2018, 106, 2412–2423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Callanan, A. Comparison of Methods for Whole-Organ Decellularization in Tissue Engineering of Bioartificial Organs. Tissue. Eng. Part B Rev. 2013, 19, 194–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knight, R.L.; Wilcox, H.E.; Korossis, S.A.; Fisher, J.; Ingham, E. The Use of Acellular Matrices for the Tissue Engineering of Cardiac Valves. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part H J. Eng. Med. 2008, 222, 129–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieder, E.; Kasimir, M.T.; Silberhumer, G.; Seebacher, G.; Wolner, E.; Simon, P.; Weigel, G. Decellularization Protocols of Porcine Heart Valves Differ Importantly in Efficiency of Cell Removal and Susceptibility of the Matrix to Recellularization with Human Vascular Cells. J. Thorac. Cardiov. Sur. 2015, 149, 1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillies, A.R.; Smith, L.R.; Lieber, R.L.; Varghese, S. Method for Decellularizing Skeletal Muscle Without Detergents or Proteolytic Enzymes. Tissue Eng. Part C Methods 2011, 17, 383–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambon, J.P.; Ko, I.K.; Abolbashari, M.; Huling, J.; Clouse, C.; Kim, T.H.; Smith, C.; Atala, A.; Yoo, J.J. Comparative Analysis of Two Porcine Kidney Decellularization Methods for Maintenance of Functional Vascular Architectures. Acta Biomater. 2018, 75, 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckenmeyer, M.J.; Meder, T.J.; Prest, T.A.; Brown, B.N. Decellularization Techniques and their Applications for the Repair and Regeneration of the Nervous System. Methods 2020, 171, 41–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrebikova, H.; Diaz, D.; Mokry, J. Chemical Decellularization: A Promising Approach for Preparation of Extracellular Matrix. Biomed. Pap. 2015, 159, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tchoukalova, Y.D.; Hintze, J.M.; Hayden, R.E.; Lott, D.G. Tracheal Decellularization Using a Combination of Chemical, Physical and Bioreactor Methods. Int. J. Artif. Organs 2018, 41, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deeken, C.R.; White, A.K.; Bachman, S.L.; Ramshaw, B.J.; Cleveland, D.S.; Loy, T.S.; Grant, S.A. Method of Preparing a Decellularized Porcine Tendon Using Tributyl Phosphate. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B 2011, 96, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-García, O.D.; El Soury, M.; Campos, F.; Sánchez-Porras, D.; Geuna, S.; Alaminos, M.; Gambarotta, G.; Chato-Astrain, J.; Raimondo, S.; Carriel, V. Comprehensive and Preclinical Evaluation of Novel Chemo Enzymatic Decellularized Peripheral Nerve Allografts. Front. Bioeng. Biotech. 2023, 11, 1162684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moffat, D.; Ye, K.M.; Jin, S. Decellularization for the Retention of Tissue Niches. J. Tissue Eng. 2022, 13, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morawski, M.; Krasnodebski, M.; Rochon, J.; Kubiszewski, H.; Marzecki, M.; Topyla, D.; Murat, K.; Staszewski, M.; Szczytko, J.; Maleszewski, M.; et al. Decellularized Liver Matrices for Expanding the Donor Pool-An Evaluation of Existing Protocols and Future Trends. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.Y.; Zhong, B.; Liu, Y.F.; Chen, F. Comparison of Anterolateral Thigh Flap with or without acellular dermal matrix in Repair of the Defect from Hypopharyngeal Squamous- Cell Carcinoma: A Retrospective Study. Asian J. Surg. 2023, 46, 1027–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, M.E.; Blum, K.M.; Watanabe, T.; Schwarz, E.L.; Nabavinia, M.; Leland, J.T.; Villarreal, D.J.; Schwartzman, W.E.; Chou, T.H.; Baker, P.B.; et al. Tissue Engineered Vascular Grafts are Resistant to the Formation of Dystrophic Calcification. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trevizani, M.; Leal, L.L.; Barros, R.J.D.; de Paoli, F.; Nogueira, B.V.; Costa, F.F.; de Aguiar, J.A.K.; Maranduba, C.M.D. Effects of Decellularization on Glycosaminoglycans and Collagen Macromolecules in Bovine Bone Extracellular Matrix. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 307, 141007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.; Li, J.Y.; Moraes, C.; Tabrizian, M.; Li-Jessen, N.Y.K. Decellularized Extracellular Matrix: New Promising and Challenging Biomaterials for Regenerative Medicine. Biomaterials 2022, 289, 121786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoganarasimha, S.; Trahan, W.R.; Best, A.; Bowlin, G.L.; Kitten, T.O.; Moon, P.C.; Madurantakam, P.A. Peracetic Acid: A Practical Agent for Sterilizing Heat-Labile Polymeric Tissue-Engineering Scaffolds. Tissue Eng. Part. C Methods 2014, 20, 714–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barajaa, M.A.; Otsuka, T.; Ghosh, D.; Kan, H.M.; Laurencin, C.T. Development of Porcine Skeletal Muscle Extracellular Matrix-Derived Hydrogels with Improved Properties and Low Immunogenicity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2322822121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sano, H.; Orbay, H.; Terashi, H.; Hyakusoku, H.; Ogawa, R. Acellular Adipose Matrix as a Natural Scaffold for Tissue Engineering. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aes. 2014, 67, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.Q.; Fan, J.; Gao, J.H.; Zhang, C.; Bai, S.L. Comparison of In Vivo Adipogenic Capabilities of Two Different Extracellular Matrix Microparticle Scaffolds. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2013, 131, 174e–187e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, I.; Nahas, Z.; Kimmerling, K.A.; Rosson, G.D.; Elisseeff, J.H. An Injectable Adipose Matrix for Soft-Tissue Reconstruction. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2012, 129, 1247–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flynn, L.E. The Use of Decellularized Adipose Tissue to Provide an Inductive Microenvironment for the Adipogenic Differentiation of Human Adipose-Derived Stem Cells. Biomaterials 2010, 31, 4715–4724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porzionato, A.; Sfriso, M.M.; Macchi, V.; Rambaldo, A.; Lago, G.; Lancerotto, L.; Vindigni, V.; De Caro, R. Decellularized Omentum as novel biologic scaffold for reconstructive surgery and regenerative medicine. Eur. J. Histochem. 2013, 57, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.N.; Johnson, J.A.; Zhang, Q.X.; Beahm, E.K. Combining Decellularized Human Adipose Tissue Extracellular Matrix and Adipose-Derived Stem Cells for Adipose Tissue Engineering. Acta Biomater. 2013, 9, 8921–8931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Zhang, X.C.; Wei, N.; Wu, X.P.; Yuan, P.P.; Zeng, T.; Liang, L.R.; Zhang, H.; Wu, W. 3D Perfusable Minichannels Stented with Matrix Bound Vesicles Derived from Gingival Mesenchymal Stem Cells Ameliorated Granuloma-Related Stenosis and Improved Survival in a Rabbit Tracheal Replacement Model. Biomaterials 2026, 327, 123769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.X.; Johnson, J.A.; Dunne, L.W.; Chen, Y.B.; Iyyanki, T.; Wu, Y.W.; Chang, E.I.; Branch-Brooks, C.D.; Robb, G.L.; Butler, C.E. Decellularized Skin/Adipose Tissue Flap Matrix for Engineering Vascularized Composite Soft Tissue Flaps. Acta Biomater. 2016, 35, 166–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.S.; Choi, J.S.; Cho, Y.W. Cell-Free Hydrogel System Based on a Tissue-Specific Extracellular Matrix for In Situ Adipose Tissue Regeneration. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 2017, 9, 8581–8588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.R.; Zheng, K.K.; Sherlock, B.E.; Zhong, J.X.; Mansfield, J.; Green, E.; Toms, A.D.; Winlove, C.P.; Chen, J.N. Zonal Characteristics of Collagen Ultrastructure and Responses to Mechanical Loading in Articular Cartilage. Acta Biomater. 2025, 195, 104–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuniakova, M.; Novakova, Z.V.; Haspinger, D.; Niestrawska, J.A.; Klein, M.; Galfiova, P.; Kovac, J.; Palkovic, M.; Danisovic, L.; Hammer, N.; et al. Effects of Two Decellularization Protocols on the Mechanical Behavior and Structural Properties of the Human Urethra. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Li, Z.M.Y.; Huang, J.; Wang, H.K.; Gu, X.S.; Gu, J.H. Application of Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Extracellular Matrix in Peripheral Nerve Tissue Engineering. J. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2017, 11, 2250–2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayashi, Y.; Yamauchi, M.; Kim, S.K.; Kusaoke, H. Biomaterials: Chitosan and Collagen for Regenerative Medicine. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 690485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunne, L.W.; Huang, Z.; Meng, W.X.; Fan, X.J.; Zhang, N.Y.; Zhang, Q.X.; An, Z.G. Human Decellularized Adipose Tissue Scaffold as a Model for Breast Cancer Cell Growth and Drug Treatments. Biomaterials 2014, 35, 4940–4949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omidi, E.; Fuetterer, L.; Mousavi, S.R.; Armstrong, R.C.; Flynn, L.E.; Samani, A. Characterization and Assessment of Hyperelastic and Elastic Properties of Decellularized Human Adipose Tissues. J. Biomech. 2014, 47, 3657–3663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Bianco, J.; Brown, C.; Fuetterer, L.; Watkins, J.E.; Samani, A.; Flynn, L.E. Porous Decellularized Adipose Tissue Foams for Soft Tissue Regeneration. Biomaterials 2013, 34, 3290–3302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindaraj, S.; Cohen, M.; Genden, E.M.; Costantino, P.D.; Urken, M.L. The Use of Acellular Dermis in the Prevention of Frey’s Syndrome. Laryngoscope 2001, 111, 1993–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyzelman, A.; Crews, R.T.; Moore, J.C.; Moore, L.; Mukker, J.S.; Offutt, S.; Tallis, A.; Turner, W.B.; Vayser, D.; Winters, C.; et al. Clinical Effectiveness of an Acellular Dermal Regenerative Tissue Matrix Compared to Standard Wound Management in Healing Diabetic Foot Ulcers: A Prospective, Randomised, Multicentre Study. Int. Wound J. 2009, 6, 196–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frykberg, R.G.; Cazzell, S.M.; Arroyo-Rivera, J.; Tallis, A.; Reyzelman, A.M.; Saba, F.; Warren, L.; Stouch, B.C.; Gilbert, T.W. Evaluation of Tissue Engineering Products for the Management of Neuropathic Diabetic Foot Ulcers: An Interim Analysis. J. Wound Care 2016, 25, S18–S25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greaves, N.S.; Iqbal, S.A.; Hodgkinson, T.; Morris, J.; Benatar, B.; Alonso-Rasgado, T.; Baguneid, M.; Bayat, A. Skin Substitute-Assisted Repair Shows Reduced Dermal Fibrosis in Acute Human Wounds Validated Simultaneously by Histology and Optical Coherence Tomography. Wound Repair Regen. 2015, 23, 483–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.; Hanna, K.R.; LeGallo, R.D.; Drake, D.B. Comparison of Histological Characteristics of Acellular Dermal Matrix Capsules to Surrounding Breast Capsules in Acellular Dermal Matrix-Assisted Breast Reconstruction. Ann. Plas. Surg. 2016, 76, 485–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, A.M.; Higdon, K.K.; Kilgo, M.S.; Tepper, D.G.; Alizadeh, K.; Glat, P.M.; Agarwal, J.P. Porcine Acellular Peritoneal Matrix in Immediate Breast Reconstruction: A Multicenter, Prospective, Single-Arm Trial. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2019, 143, 10e–21e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Zou, R.; He, J.Q.; Ouyang, K.X.; Piao, Z.G. Comparing Osteogenic Effects between Concentrated Growth Factors and the Acellular Dermal Matrix. Braz. Oral Res. 2018, 32, e29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, C.L.; Wang, L.Y.; Feng, J.W.; Lu, F. Treatment of Human Chronic Wounds with Autologous Extracellular Matrix/Stromal Vascular Fraction Gel: A STROBE-Compliant Study. Medicine 2018, 97, e11667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitala, D.; Klama-Baryla, A.; Labus, W.; Kraut, M.; Glik, J.; Kawecki, M.; Joszko, K.; Gzik-Zroska, B. Porcine Transgenic, Acellular Material as an Alternative for Human Skin. Transplant. Proc. 2020, 52, 2218–2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Kassaby, A.; AbouShwareb, T.; Atala, A. Randomized Comparative Study between Buccal Mucosal and Acellular Bladder Matrix Grafts in Complex Anterior Urethral Strictures. J. Urol. 2008, 179, 1432–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yanagawa, B.; Rao, V.; Yau, T.M.; Cusimano, R.J. Initial Experience with Intraventricular Repair Using CorMatrix Extracellular Matrix. Innovations 2013, 8, 348–352. [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins, R.A.; Lofland, G.K.; Marshall, J.; Connelly, D.; Acharya, G.; Dennis, P.; Stroup, R.; O’Brien, J.E. Pulmonary Arterioplasty with Decellularized Allogeneic Patches. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2014, 97, 1407–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarikouch, S.; Horke, A.; Tudorache, I.; Beerbaum, P.; Westhoff-Bleck, M.; Boethig, D.; Repin, O.; Maniuc, L.; Ciubotaru, A.; Haverich, A.; et al. Decellularized Fresh Homografts for Pulmonary Valve Replacement: A Decade of Clinical Experience. Eur. J. Cardio-Thorac. Surg. 2016, 50, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cevallos, C.A.R.; de Resende, D.R.B.; Damante, C.A.; Sant’Ana, A.C.P.; de Rezende, M.L.R.; Greghi, S.L.A.; Zangrando, M.S.R. Free Gingival Graft and Acellular Dermal Matrix for Gingival Augmentation: A 15-Year Clinical Study. Clin. Oral. Investig. 2020, 24, 1197–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, R.; Das, P.; Joardar, S.N.; Biswas, B.K.; Batabyal, S.; Das, P.K.; Nandi, S.K. Novel Decellularized Animal Conchal Cartilage Graft for Application in Human Patient. J. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2019, 13, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teng, Y.J.; Zhang, X.H.; Song, L.; Yang, J.N.; Li, D.; Shi, Z.Q.; Guo, X.Q.; Wang, S.F.; Fan, H.J.; Jiang, L.; et al. Construction of Anti-Calcification Small-Diameter Vascular Grafts Using Decellularized Extracellular Matrix/Poly (L-Lactide-Co-Ε-Caprolactone) and Baicalin-Cathepsin S Inhibitor. Acta Biomater. 2025, 197, 184–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayam, R.; Hamias, S.; Moshe, M.S.; Davidov, T.; Yen, F.C.; Baruch, L.; Machluf, M. Porcine Bone Extracellular Matrix Hydrogel as a Promising Graft for Bone Regeneration. Gels 2025, 11, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, D.L.; Chen, Z.X.; Guo, K.M.; Xie, Q.Q.; Zou, Y.X.; Mou, Q.Z.; Zhou, Z.J.; Jin, G.X. Enhanced Viability and Functional Maturity of iPSC-Derived Islet Organoids by Collagen-Vi-Enriched ECM Scaffolds. Cell Stem Cell 2025, 32, 547–563.E7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, H.S.; Lee, G.; Park, S.; Ha, J.; Choi, D.; Ko, J.H.; Ahn, J. Reconstructing the Female Reproductive System Using 3D Bioprinting in Tissue Engineering. Mater. Today Bio 2025, 34, 102127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Core Difference | Organ-Derived ECM | Cell-Derived ECM | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sources | limited source of donor material | abundant sources | [15] |

| Immunogenicity risk | potential host immune response | greatly reduce the potential host response | [16] |

| Customizability of structure | structural fixation | prepared according to needs | [16] |

| Scale potential | NO | YES | [16] |

| Scalability | weak scalability | relatively flexible | [15,16] |

| Category | Treatment/Technique | Core Principle | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical | Freeze–thaw cycling |

| [26,29] |

| Mechanical stirring |

| [27,30] | |

| Electroporation |

| [31,32] | |

| Pressure |

| [33,34,35,36,37] | |

| Supercritical fluid |

| [38,39,40,41] | |

| Chemical | Acids and bases |

| [42,43,44,45,46] |

| Non-ionic detergents |

| [47,48,49,50,51,52,53] | |

| Ionic detergents |

| [54,55,56,57,58] | |

| Zwitterionic detergent |

| [59,60] | |

| Hypotonic/hypertonic solutions |

| [61] | |

| Alcohols |

| [27,54] | |

| Biological methods | Trypsin |

| [62] |

| Nucleases |

| [63] | |

| Non-enzymatic agents |

| [64,65,66,67] |

| Decellularized Extracellular Matrix | Publication | Pub. No. | Pub. Date |

|---|---|---|---|

| Decellularized engineered tissues by growing cells on a substrate and decellularizing | United States Patent Application Publication | US2002/0115208 A1 | 2002/08/22 |

| Decellularization method that contains enzymatic proteolytic digestion, nucleic acid removal, and cellular component removal | World Intellectual Property Organization, International Bureau | WO 2006/095342 A2 | 2006/09/14 |

| Fabricated chondrocyte extracellular matrix from cartilage derived-chondrocytes by centrifuging and freeze-drying | World Intellectual Property Organization, International Bureau | WO 2008/126952 A1 | 2008/10/23 |

| Decellularized extracellular matrix derived from the native or natural matrix of heart tissue | World Intellectual Property Organization, International Bureau | WO 2010/039823 A2 | 2010/04/08 |

| Decellularized scaffolds with porous structures obtained by freeze-drying/lyophilizing bio-scaffolds and using detergent and alkaline solution | United States Patent Application Publication | US2012/0259415 A1 | 2012/10/11 |

| Muscle implants comprising decellularized muscle matrices | World Intellectual Property Organization, International Bureau | WO 2014/008181 A2 | 2014/01/09 |

| Decellularization using detergent perfusing, neutral buffer rinsing, and DNase solution delivery | United States Patent Application Publication | US2015/0238656 A1 | 2015/08/27 |

| Decellularization by subjecting detergent-treated tissue samples to oscillation at a certain frequency | World Intellectual Property Organization, International Bureau | WO 2017/017474 A1 | 2017/02/02 |

| Decellularization via non-thermal irreversible electroporation | United States Patent Application Publication | US2017/0209620 A1 | 2017/07/27 |

| Bio-inks containing decellularized extracellular matrix | World Intellectual Property Organization, International Bureau | WO 2018/094166 A1 | 2018/05/24 |

| Decellularization by closing afferent blood vessels to substantially seal a donor lobular organ with no common artery, eradicating blood, and perfusing detergent and enzymatic solutions | World Intellectual Property Organization, International Bureau | WO 2019/220091 A1 | 2019/11/21 |

| Decellularized Extracellular Matrix | Publication | Pub. No. | Pub. Date |

|---|---|---|---|

| Decellularized biphasic periodontal tissue grafts comprising interconnected polymer fiber scaffolds | World Intellectual Property Organization, International Bureau | WO 2016/049682 A1 | 2016/04/07 |

| Decellularized extracellular matrix incorporated with a synthetic polymer | World Intellectual Property Organization, International Bureau | WO 2021/202974 A1 | 2021/10/07 |

| Category | Disease/Application Area | Product/Trial Name | Company/Institution | Outcome | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical Trial | Frey’s Syndrome | Acellular dermis (AlloDerm®) | LifeCell Corp. | Reduced gustatory sweating and complication rate | [98] |

| Diabetic foot ulcer | Acellular dermal graft (Graftjacket®) | Wright Medical Technology | Complete wound closure in 12 out of 14 patients | [9,99] | |

| Non-healing diabetic foot ulcers | MatriStem® Wound Matrix | ACell, Inc. | Improved quality of life and reduced cost | [100] | |

| Clinical Trial | Wound regeneration | Decellularized dermis | - | Reduced fibrosis and thicker regenerated dermis | [101] |

| Breast reconstruction | Acellular dermal matrix (DermACELL®) | LifeNet Health | Less inflammation, fewer myofibroblasts, and decreased capsular contracture | [102] | |

| Breast reconstruction | Bovine-derived acellular dermal matrix (SurgiMend®) | TEI Biosciences | Reduced immunogenicity, low implant loss, high patient satisfaction | [10] | |

| Breast reconstruction | Porcine-derived acellular peritoneal matrix (Meso BioMatrix®) | DSM Biomedical | Identified as a safe adjunct | [103] | |

| Alveolar cleft | Acellular dermal matrix heterograft (Heal-All®) | Zhenghai Biotechnology Co., Ltd. | Increased osteogenic effect and bone formation | [104] | |

| Chronic wounds | Autologous ECM/stromal vascular fraction gel | - | Increased wound healing rate, reduced lymphocyte infiltration, elevated collagen and vessel formation | [105] | |

| Severe burns | Acellular skin from transgenic porcine | - | Reduced pain intensity and shorter hospitalization | [106] | |

| Urethral stricture | Acellular bladder matrix grafts | - | High recovery rate, comparable to buccal mucosal grafts | [107] | |

| Post myocardial infarction complications | CorMatrix® ECM (porcine SIS) | CorMatrix Cardiovascular Inc. | High stability, safety, and efficacy as a pericardial patch | [108] | |

| Tympanic membrane perforation | Porcine SIS (SurgiSIS®) | Cook Surgical | Stable tympanic membrane closures in 209/217 children | [11] | |

| Pulmonary valve replacement | Decellularized allogeneic pulmonary artery patches (MatrACELL®) | LifeNet Health | No serious adverse effects, failure, or reoperation | [109] | |

| Pulmonary valve replacement | Decellularized homografts | - | Reduced re-operation rates | [110] | |

| Nerve defects | Acellular nerve grafts | - | A high excellent and good rate | [12] | |

| Market Product | Wound healing | Biodesign® (SIS) | Evergen (formerly Cook Biotech, Alachua, FL, USA) | Commercially available for soft tissue repair and wound management | - |

| Wound healing | OASIS® (SIS) | Evergen (formerly Cook Biotech, Alachua, FL, USA) | Commercially available for acute and chronic wound treatment | - | |

| Cardiovascular repair | Decellularized pulmonary heart valve | Artivion (formerly Cryolife, Kennesaw, GA, USA) | Marketed since the late 2000s for pulmonary valve replacement | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yang, H.; Xia, J.; Qian, Y.; Gu, X.; Cong, M. From Production to the Clinic: Decellularized Extracellular Matrix as a Biomaterial for Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine. Bioengineering 2026, 13, 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering13010024

Yang H, Xia J, Qian Y, Gu X, Cong M. From Production to the Clinic: Decellularized Extracellular Matrix as a Biomaterial for Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine. Bioengineering. 2026; 13(1):24. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering13010024

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Haochen, Jiesheng Xia, Yuyue Qian, Xiaosong Gu, and Meng Cong. 2026. "From Production to the Clinic: Decellularized Extracellular Matrix as a Biomaterial for Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine" Bioengineering 13, no. 1: 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering13010024

APA StyleYang, H., Xia, J., Qian, Y., Gu, X., & Cong, M. (2026). From Production to the Clinic: Decellularized Extracellular Matrix as a Biomaterial for Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine. Bioengineering, 13(1), 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering13010024