AI-Based Augmented Reality Microscope for Real-Time Sperm Detection and Tracking in Micro-TESE

Abstract

1. Introduction

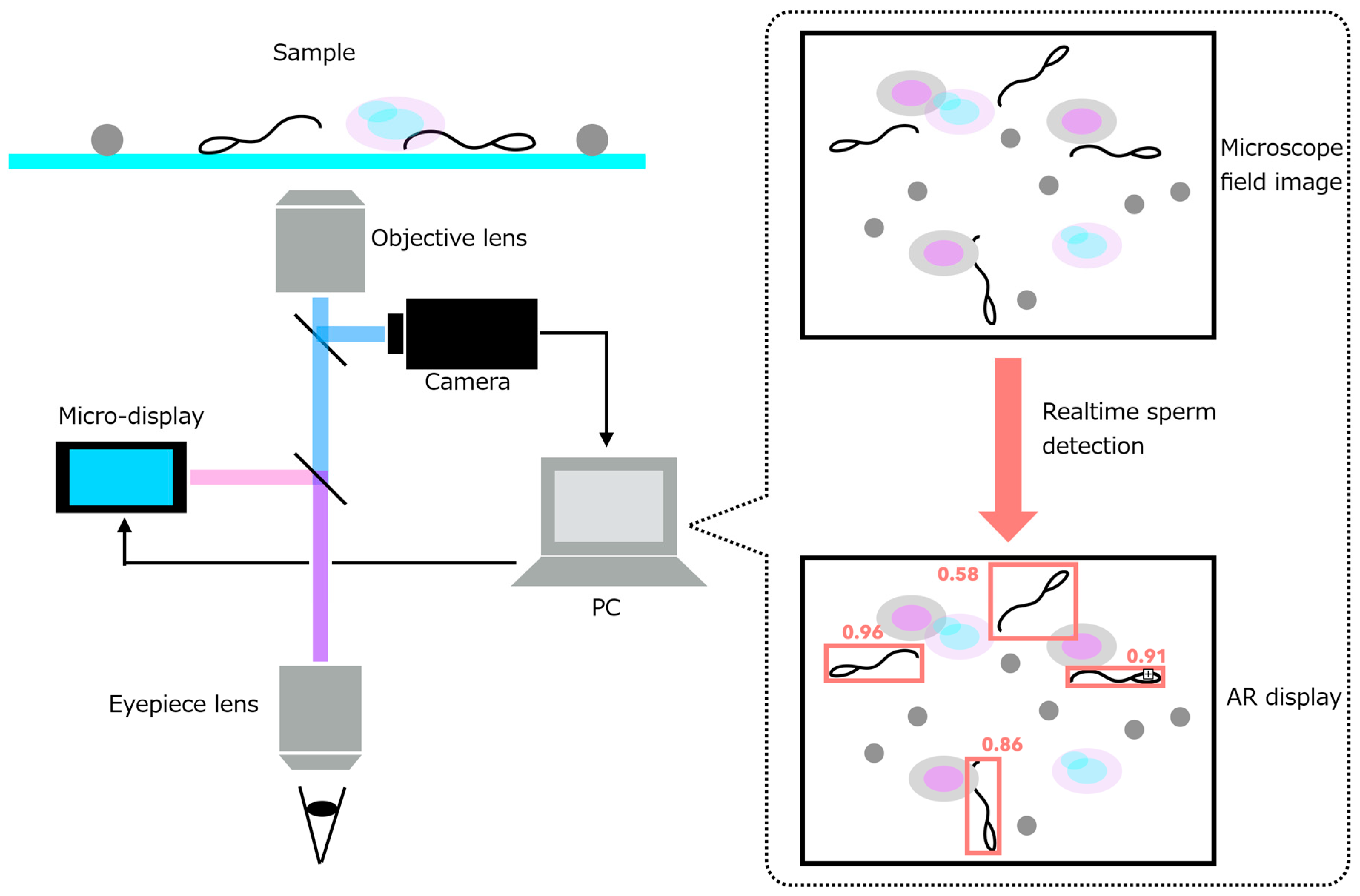

- (1)

- an AR microscope capable of extracting image features from a high-speed camera feed and projecting them into the visual path at interactive rates, and

- (2)

- a real-time sperm-analysis module that performs sperm detection, tracking, and motility-related speed analysis.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Preparation

- (1)

- Prepare a cell suspension: thaw frozen HepG2 (human liver cancer-derived) cells and add 1 mL of PBS (−).

- (2)

- Transfer 1 mL of the cell suspension into an Eppendorf tube, add 10 µL of human sperm suspension (derived from healthy donor semen), and mix thoroughly.

- (3)

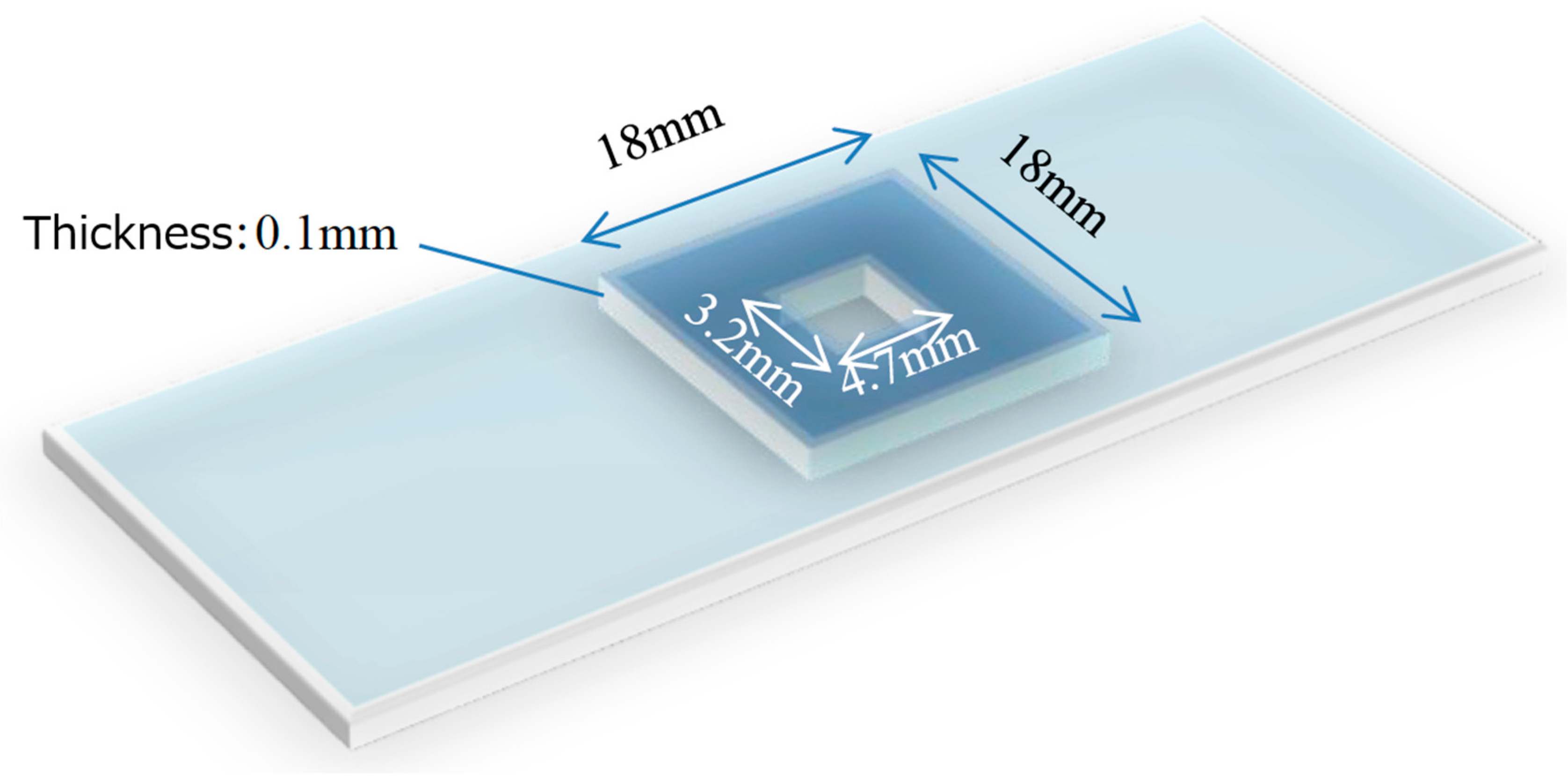

- Deposit 5 µL of the mixture onto a partitioned slide glass (Figure 2).

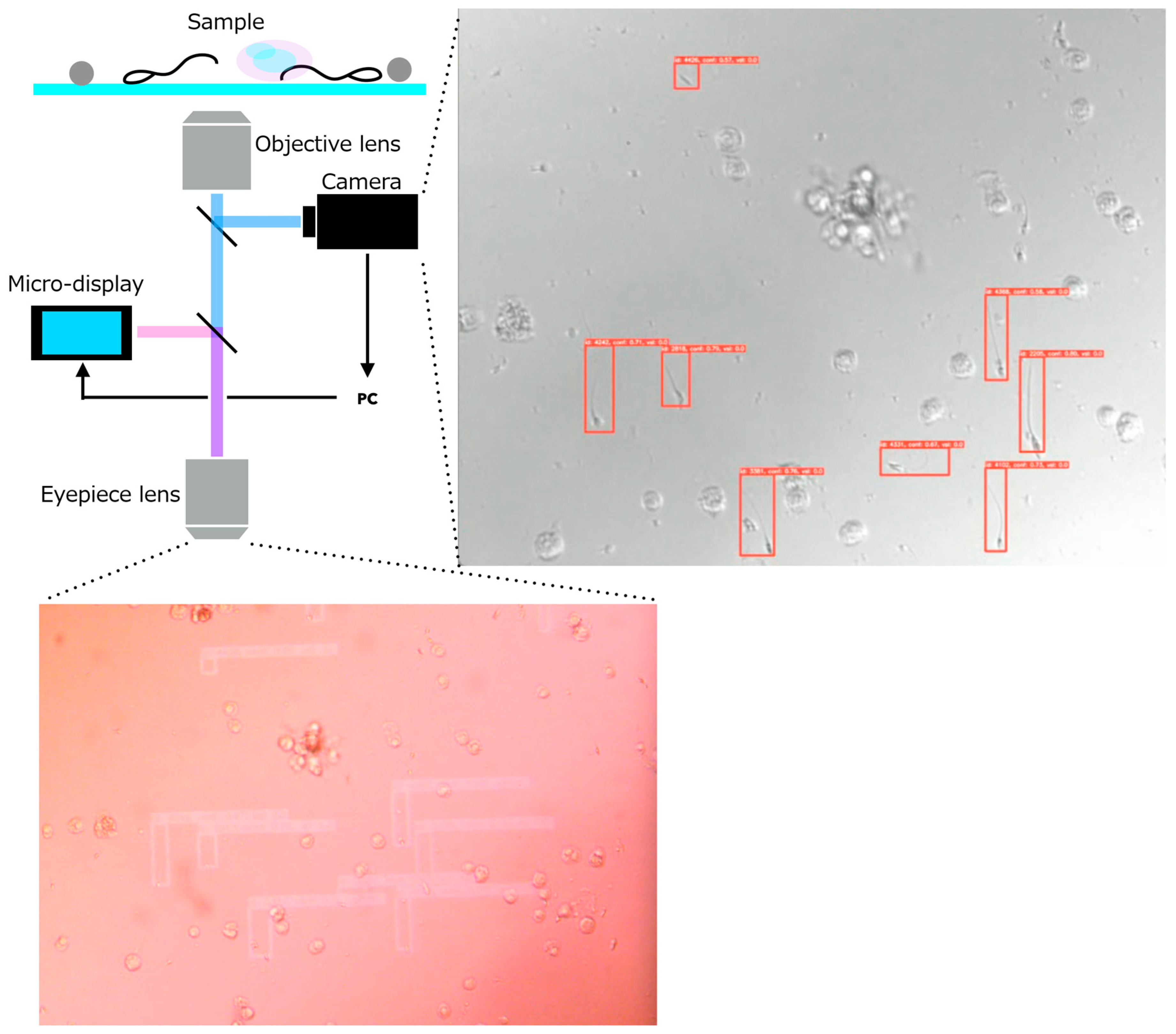

2.2. Requirements and System Design of the AR Microscope for Sperm Retrieval Support

- (1)

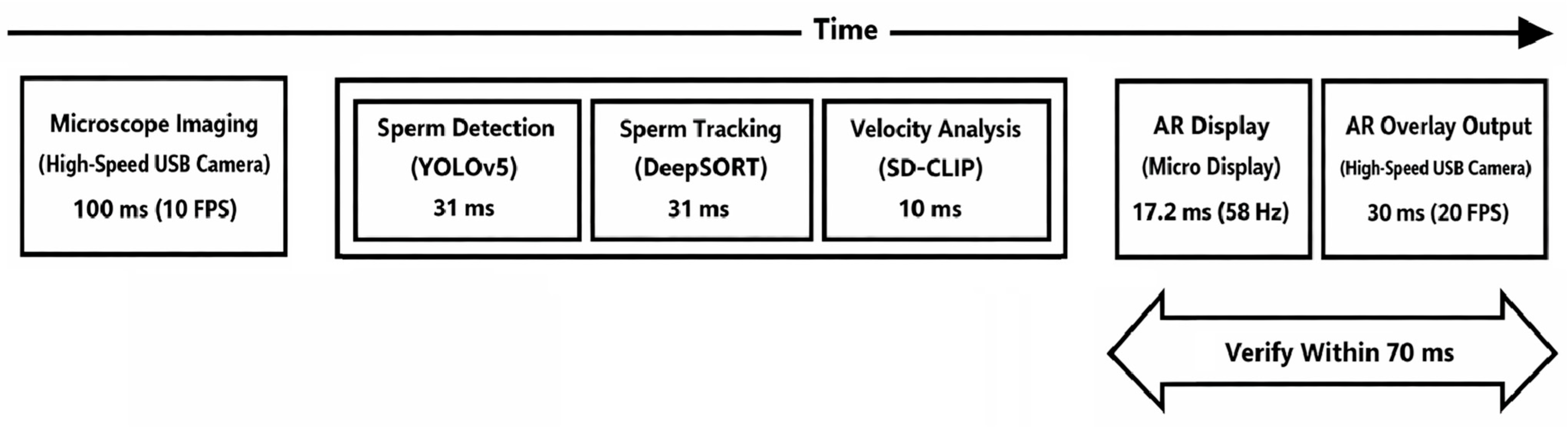

- Response time from acquisition of the microscope image to AR overlay projection must be within 200 ms.

- (2)

- When using a 10× objective lens, the imaging system must resolve the size of spermatozoa (total length: ~50 µm; head short axis: ~3 µm; tail diameter: 0.2–0.3 µm).

- (3)

- The sperm-analysis software must operate on a portable notebook PC, enabling deployment within clinical environments such as operating rooms.

- •

- A high-resolution camera module that captures the current microscopic field of view.

- •

- A micro-display module that overlays digital information directly onto the original optical path.

- •

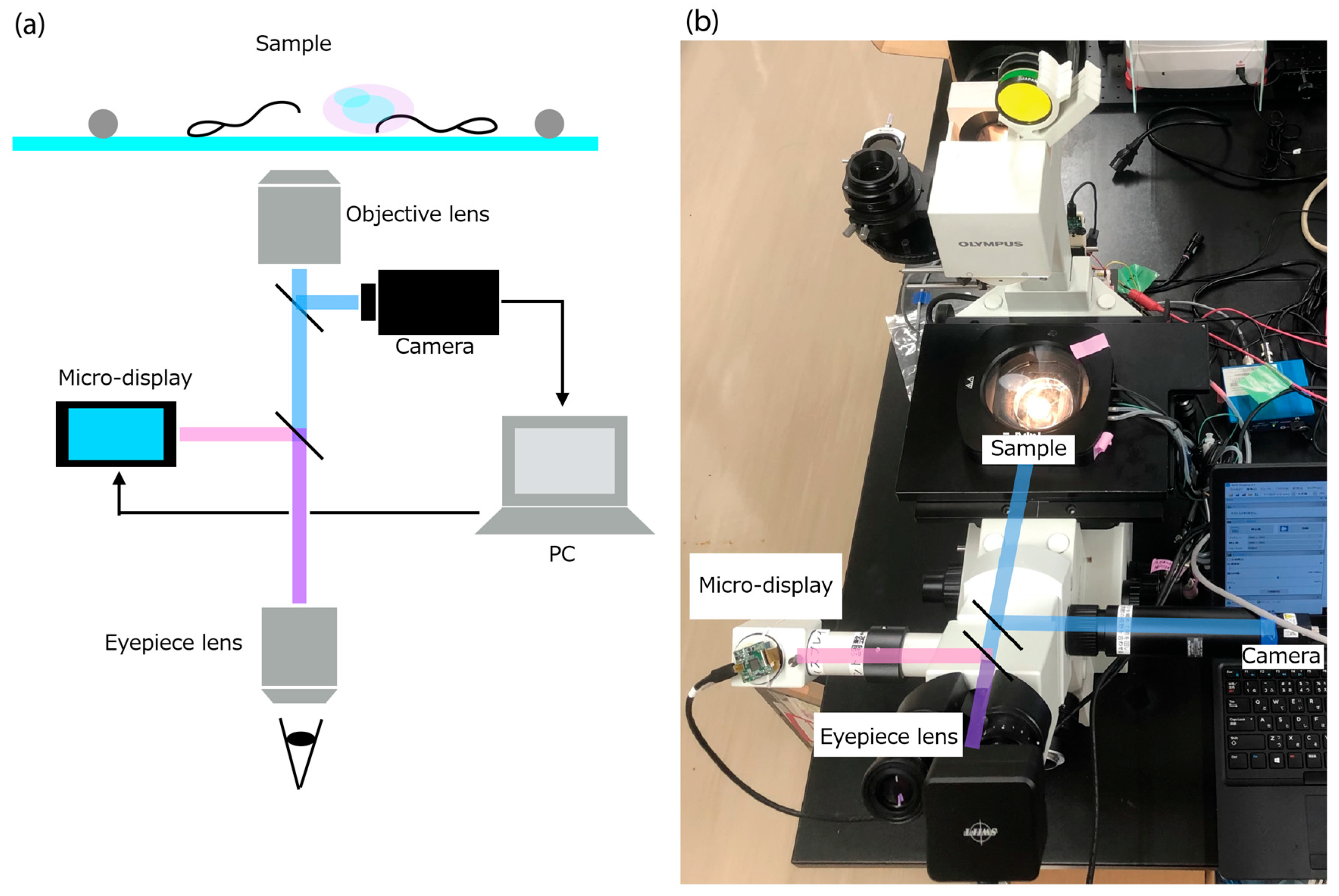

- Inverted fluorescence microscope: IX70 (Olympus, Hachioji, Japan)

- •

- High-speed USB camera: STC-MBS510U3V (OMRON SENTECH, Ebina, Japan)

- ○

- Frame rate: 75.7 FPS

- ○

- Effective pixels: 2448 × 2048 (grayscale)

- •

- Micro-display: ECX334C (Sony, Minato-ku, Japan)

- ○

- Refresh rate: 57.942 Hz

- ○

- Resolution: 1024 × 768 (RGB)

- ○

- Maximum brightness: 1000 cd/m2

- ○

- Contrast ratio: 100,000:1

2.3. Sperm Detection Model

- (1)

- Image classification: Identifying only the object category in an image

- (2)

- Object detection: Estimating the positions and classes of multiple objects using bounding boxes

- (3)

- Semantic segmentation: Assigning a class label to each pixel

2.4. Evaluation of Sperm Motility

- (1)

- higher measurement precision, and

- (2)

- quantitative acquisition of kinematic parameters such as progressive motility, hyperactivation, and capacitation-related changes.

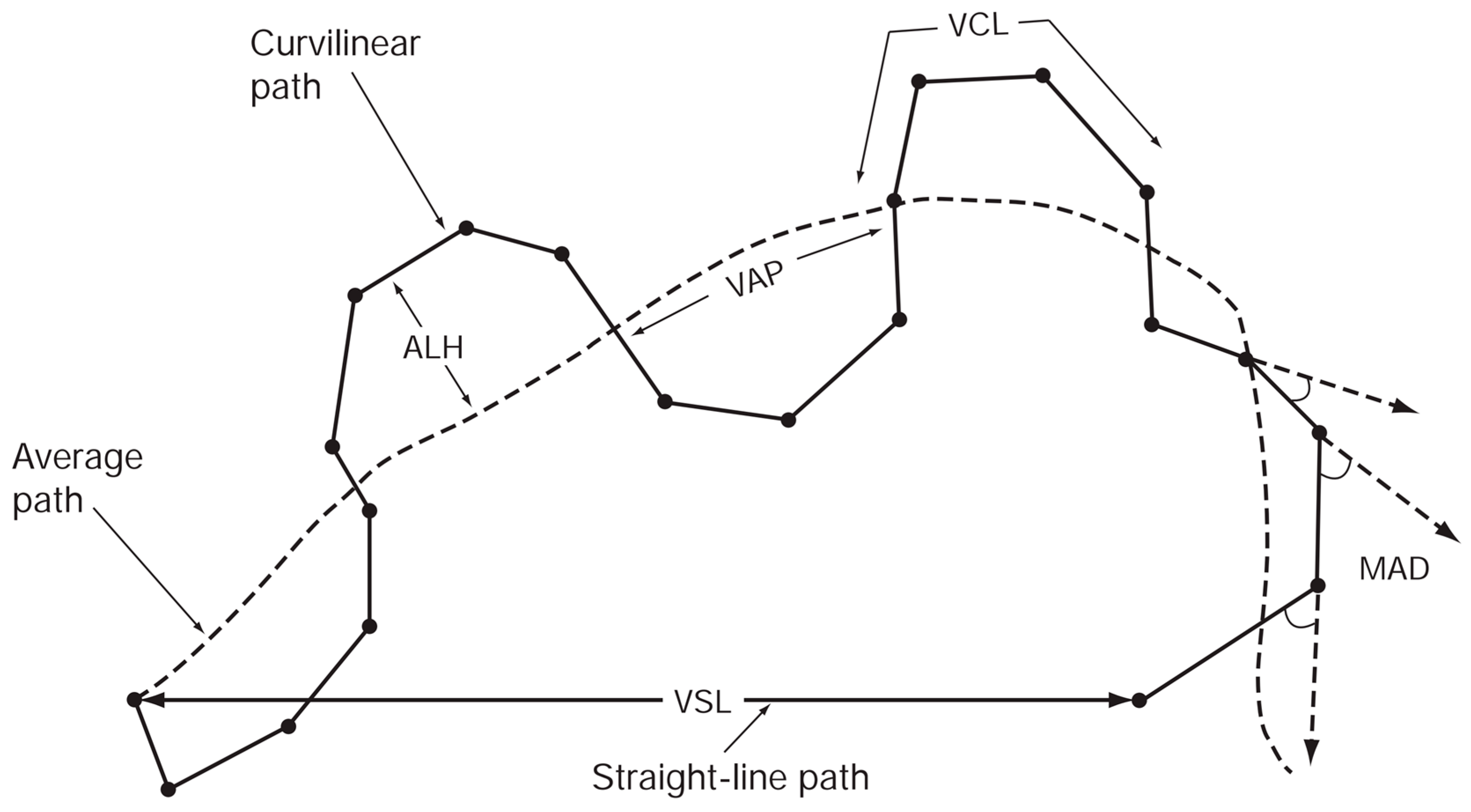

- (1)

- VCL (curvilinear velocity, µm/s): Time-averaged velocity of the sperm head along the actual curved trajectory observed in two dimensions under the microscope; an indicator of cellular vigor.

- (2)

- VSL (straight-line velocity, µm/s): Time-averaged velocity along the straight line connecting the first and last detected head positions.

- (3)

- VAP (average path velocity, µm/s): Time-averaged velocity along a smoothed average trajectory connecting the initial and final positions. The average path is obtained by smoothing the curved trajectory according to proprietary CASA algorithms, which can differ among systems and therefore may limit inter-system comparability.

- (4)

- ALH (amplitude of lateral head displacement, µm): Magnitude of lateral deviation of the sperm head from its average path, expressed as the maximum or mean displacement. Because algorithms differ among CASA systems, ALH values may not be directly comparable between systems.

- (5)

- LIN (linearity): Straightness of the curvilinear path, defined as VSL/VCL.

- (6)

- WOB (wobble): Degree of oscillation of the actual trajectory around the average path, defined as VAP/VCL.

- (7)

- STR (straightness): Straightness of the average path, defined as VSL/VAP.

- (8)

- BCF (beat-cross frequency, Hz): Average frequency at which the curvilinear path crosses the average path.

- (9)

- MAD (mean angular displacement, degrees): Time-averaged absolute instantaneous turning angle of the sperm head along its curved trajectory.

2.5. Sperm Tracking Model

- •

- high-speed operation, and

- •

- robust tracking even when objects temporarily disappear behind occlusions and then reappear.

2.6. Sperm Velocity Analysis

2.7. Evaluation Metrics

3. Results and Discussion

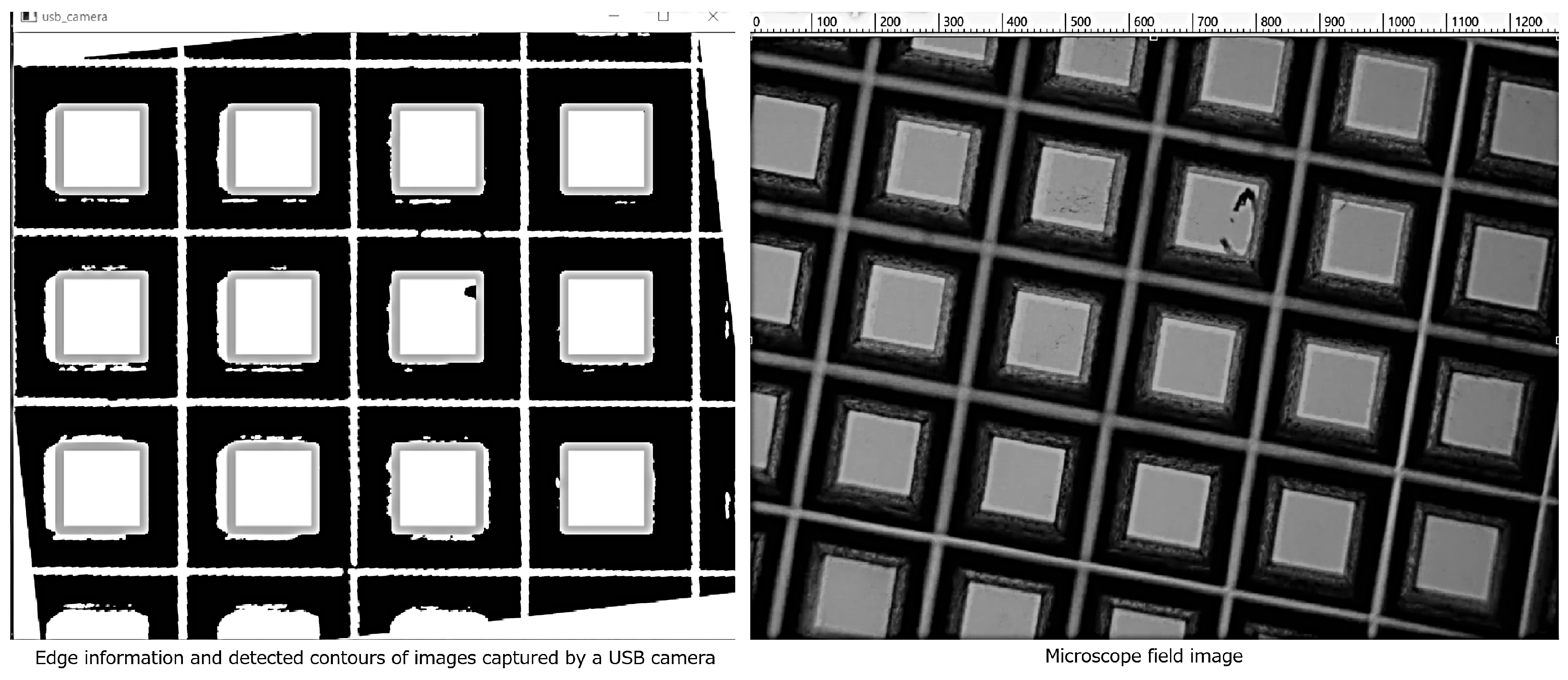

3.1. Evaluation of the AR-Display Microscope System

- •

- 2 × 2 binning in both vertical and horizontal directions

- •

- Gain set to 128

3.2. Evaluation of the Sperm Detection Model

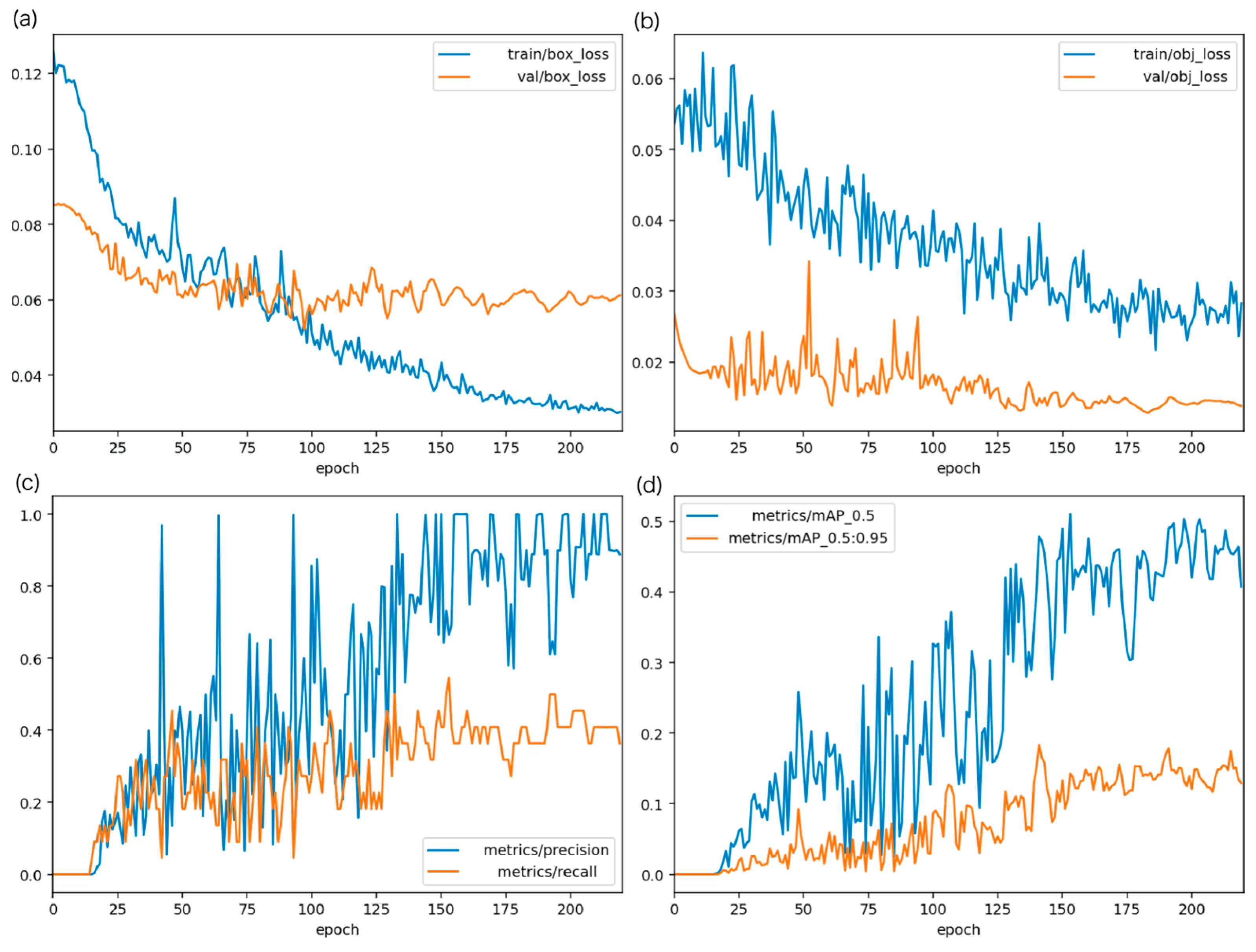

3.2.1. Training Conditions for the Sperm Detection Model

- •

- Model: YOLOv5s

- •

- Epochs: 220

- •

- Image size: 640

- •

- Optimizer: Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD)

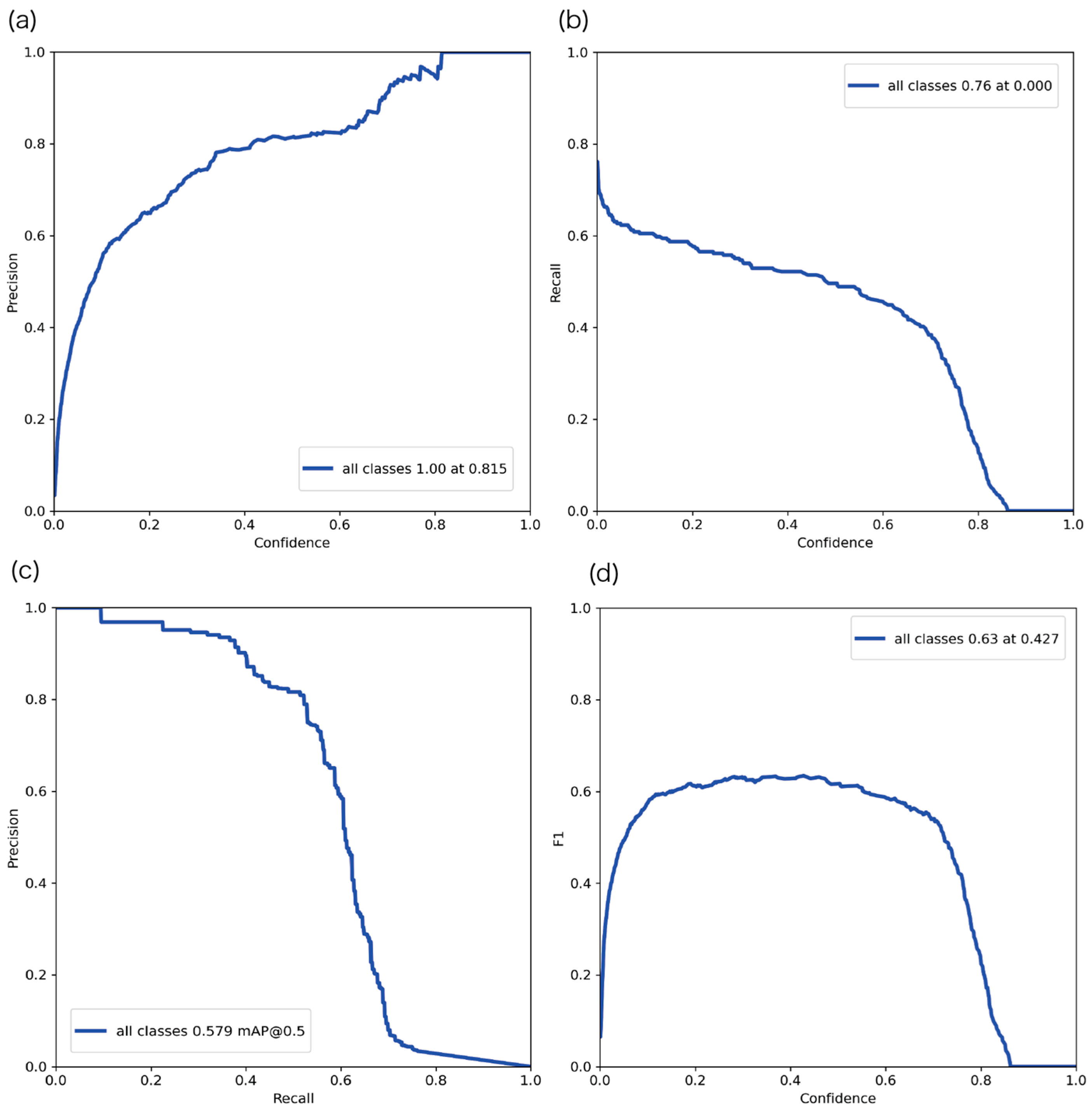

3.2.2. Evaluation Results of the YOLOv5 Sperm Detection Model

3.2.3. Comparison with Previous Detection Methods

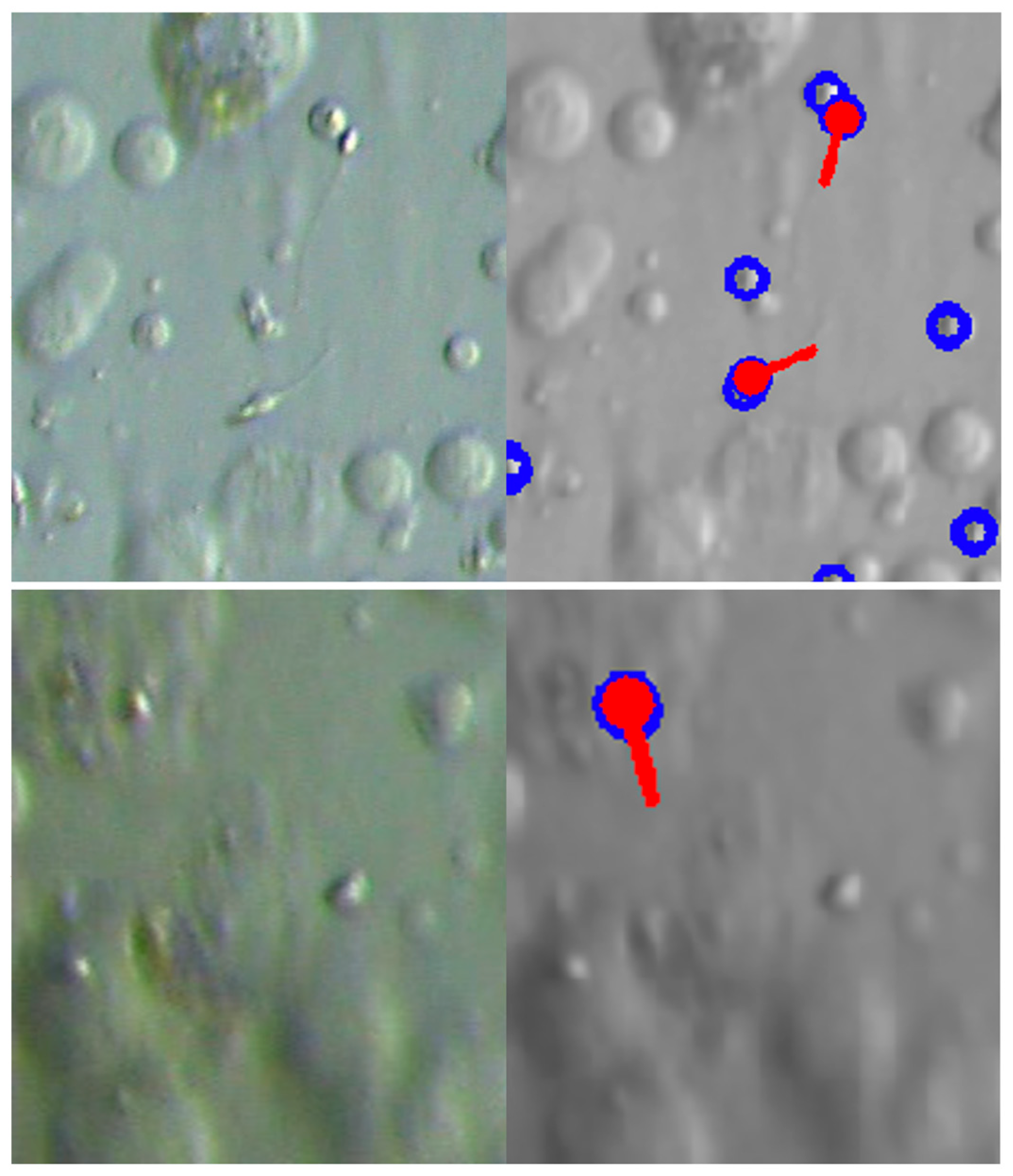

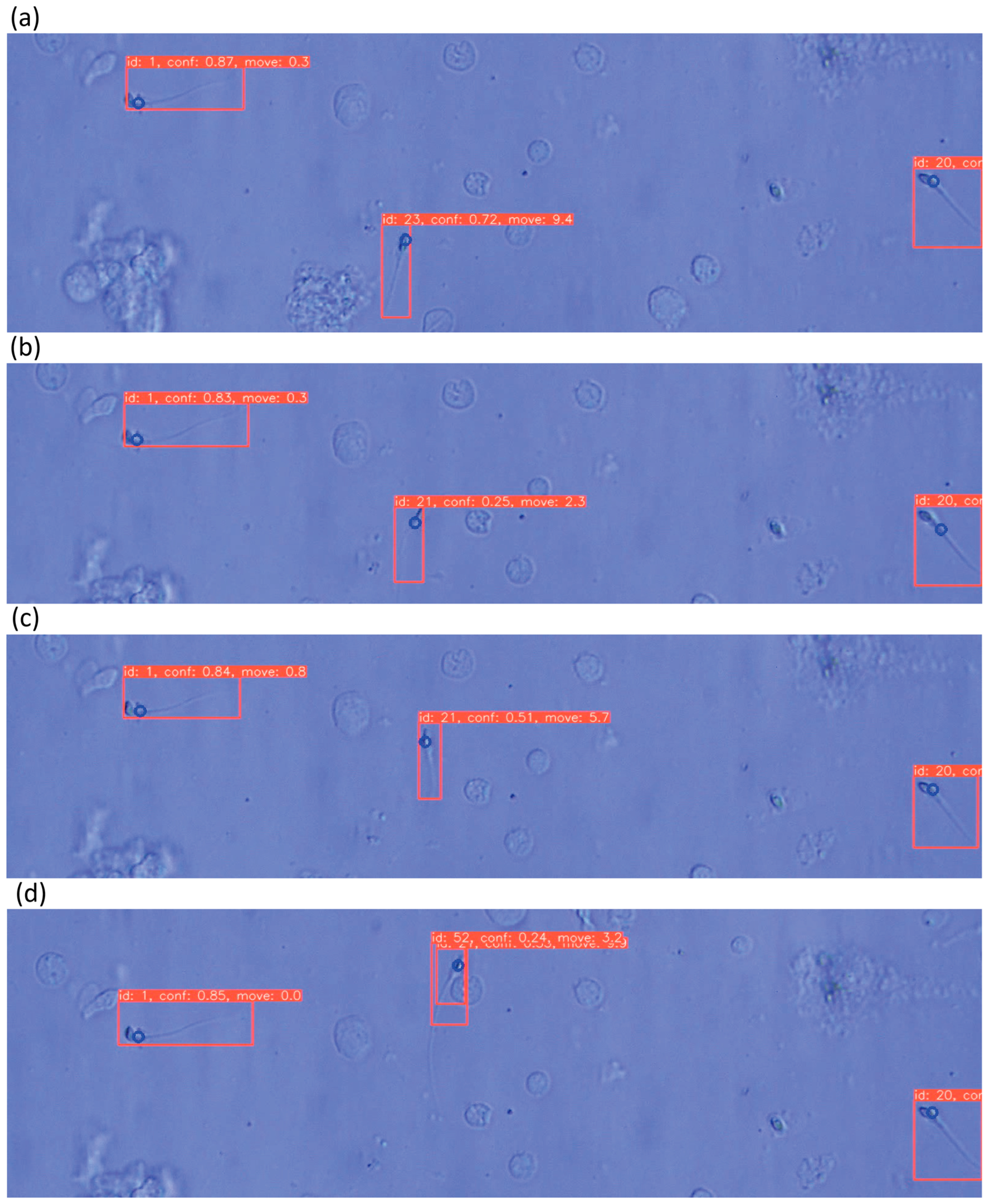

3.2.4. Examples of Actual Detection Results of the Proposed Model

3.3. Evaluation of Sperm Dynamic Analysis

3.4. Evaluation of the Entire Proposed System

4. Conclusions and Future Work

- •

- Construction of an AR microscope system

- •

- Development of a real-time sperm analysis software suite, including:

- ○

- Sperm detection

- ○

- Sperm tracking

- ○

- Sperm velocity estimation

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ART | Assisted reproductive technology |

| ET | Embryo transfer |

| IVF | in vitro fertilization |

| ICSI | Intracytoplasmic sperm injection |

| FET | Frozen–thawed embryo transfers |

| Micro-TESE | Microdissection testicular sperm extraction |

| NOA | Non-obstructive azoospermia |

| AR | Augmented reality |

| ARM | Augmented reality microscope |

| FPS | Frames per second |

| SD-CLIP | Sperm Detection using Classical Image Processing |

| YOLO | You Only Look Once |

| SSD | Single Shot MultiBox Detector |

| CASA | Computer-Aided Sperm Analysis |

| VCL | Curvilinear velocity |

| VSL | Straight-line velocity |

| VAP | Average path velocity |

| ALH | Amplitude of lateral head displacement |

| LIN | Linearity |

| WOB | Wobble |

| STR | straightness |

| BCF | Beat-cross frequency |

| MAD | Mean angular displacement |

| MOT | Multi-Object Tracking |

| SORT | Simple Online and Realtime Tracking |

| IoU | Intersection over Union |

| PR | Precision–Recall |

| AP | Average Precision |

| mAP | mean Average Precision |

| SGD | Stochastic Gradient Descent |

References

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (Japan). Outline of Vital Statistics Annual (Provisional), 2020; Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare: Tokyo, Japan, 2021. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/jinkou/geppo/nengai20/index.html (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Japan Association of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Assisted Reproductive Technology (ART). 2021. Available online: https://www.jaog.or.jp/lecture/11-%E7%94%9F%E6%AE%96%E8%A3%9C%E5%8A%A9%E5%8C%BB%E7%99%82%EF%BC%88art%EF%BC%89/ (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Katagiri, Y.; Jwa, S.C.; Kuwahara, A.; Iwasa, T.; Ono, M.; Kato, K.; Kishi, H.; Kuwabara, Y.; Taniguchi, F.; Harada, M.; et al. Assisted reproductive technology in Japan: A summary report for 2022 by the Ethics Committee of the Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology. Reprod. Med. Biol. 2024, 23, e12620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlegel, P.N. Testicular sperm extraction: Microdissection improves sperm yield with minimal tissue excision. Hum. Reprod. 1999, 14, 131–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, P.C.; Gadepalli, K.; MacDonald, R.; Liu, Y.; Kadowaki, S.; Nagpal, K.; Kohlberger, T.; Dean, J.; Corrado, G.S.; Hipp, J.D.; et al. An augmented reality microscope with real-time artificial intelligence integration for cancer diagnosis. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 1453–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dott, H.M.; Foster, G.C. The estimation of sperm motility in semen, on a membrane slide, by measuring the area change frequency with an image analysing computer. J. Reprod. Fertil. 1979, 55, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nafisi, V.R.; Moradi, M.H.; Nasr-Esfahani, M.H. Sperm identification using elliptic model and tail detection. Int. J. Med. Health Sci. 2005, 1, 400–403. [Google Scholar]

- Alcantarilla, P.; Nuevo, J.; Bartoli, A. Fast explicit diffusion for accelerated features in nonlinear scale spaces. In Proceedings of the British Machine Vision Conference, Bristol, UK, 9–13 September 2013; BMVA Press: Durham, UK, 2013; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Chu, R.; Xiang, S.; Liao, S.; Li, S.Z. Face detection based on multi-block lbp representation. In Advances in Biometrics; Lee, S.-W., Li, S.Z., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; pp. 11–18. [Google Scholar]

- Freund, Y.; Schapire, R.E. A desicion-theoretic generalization of on-line learning and an application to boosting. In Computational Learning Theory; Vitanyi, P., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1995; pp. 23–37. [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki, H.; Nakata, M.; Yamamoto, M.; Takeshima, T.; Yumura, Y.; Hamagami, T. Investigation about control of false positive rate for automatic sperm detection in assisted reproductive technology. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics (SMC), Miyazaki, Japan, 7–10 October 2018; pp. 1964–1969. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed, M.; Kachi, K.; Motoya, K.; Ikeuchi, M. Fast and Accurate Sperm Detection Algorithm for Micro-TESE in NOA Patients. Bioengineering 2025, 12, 601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lowe, D.G. Distinctive image features from scale-invariant keypoints. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2004, 60, 91110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bay, H.; Tuytelaars, T.; Gool, L.V. Surf: Speeded up robust features. In Computer Vision—ECCV 2006; Leonardis, A., Bischof, H., Pinz, A., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; pp. 404–417. [Google Scholar]

- Viola, P.; Jones, M. Rapid object detection using a boosted cascade of simple features. In Proceedings of the 2001 IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, CVPR 2001, Kauai, HI, USA, 8–14 December 2001; Volume 1, p. I. [Google Scholar]

- Girshick, R.; Donahue, J.; Darrell, T.; Malik, J. Rich feature hierarchies for accurate object detection and semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Columbus, OH, USA, 23–28 June 2014; pp. 580–587. [Google Scholar]

- The PASCAL VOC Project. The Pascal Visual Object Classes Homepage. 2021. Available online: http://host.robots.ox.ac.uk/pascal/VOC/ (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Girshick, R. Fast r-cnn. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Santiago, Chile, 7–13 December 2015; IEEE Computer Society: Los Alamitos, CA, USA, 2015; pp. 1440–1448. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster r-cnn: Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Cortes, C., Lawrence, N., Lee, D., Sugiyama, M., Garnett, R., Eds.; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2015; Volume 28. [Google Scholar]

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A. You only look once: Unified, real-time object detection. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 779–788. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Szegedy, C.; Reed, S.; Fu, C.; Berg, A.C. Ssd: Single shot multibox detector. In Computer Vision—ECCV 2016; Leibe, B., Matas, J., Sebe, N., Welling, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 21–37. [Google Scholar]

- Ultralytics. Yolov5 in Pytorch. 2021. Available online: https://github.com/ultralytics/yolov5 (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- DITECT Co., Ltd. SMAS—Sperm Motility Analysis System. Available online: https://www.ditect.co.jp/smas/ (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Liu, D.Y.; Clarke, G.N.; Baker, H.W. Relationship between sperm motility assessed with the Hamilton-Thorn motility analyzer and fertilization rates in vitro. J. Androl. 1991, 12, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barratt, C.L.; Tomlinson, M.J.; Cooke, I.D. Prognostic significance of computerized motility analysis for in vivo fertility. Fertil. Steril. 1993, 60, 520–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irvine, D.S.; Macleod, I.C.; Templeton, A.A.; Masterton, A.; Taylor, A. A prospective clinical study of the relationship between the computer-assisted assessment of human semen quality and the achievement of pregnancy in vivo. Hum. Reprod. 1994, 9, 2324–2334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrett, C.; Baker, H.W. A new fully automated system for the morphometric analysis of human sperm heads. Fertil. Steril. 1995, 63, 1306–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menkveld, R.; Lacquet, F.A.; Kruger, T.F.; Lombard, C.J.; Sanchez Sarmiento, C.A.; de Villiers, A. Effects of different staining and washing procedures on the results of human sperm morphology evaluation by manual and computerised methods. Andrologia 1997, 29, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bewley, A.; Ge, Z.; Ott, L.; Ramos, F.; Upcroft, B. Simple online and realtime tracking. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP), Phoenix, AZ, USA, 25–28 September 2016; pp. 3464–3468. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Who Laboratory Manual for the Examination and Processing of Human Semen; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wojke, N.; Bewley, A.; Paulus, D. Simple online and realtime tracking with a deep association metric. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP), Beijing, China, 17–20 September 2017; pp. 3645–3649. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, L.; Bie, Z.; Sun, Y.; Wang, J.; Su, C.; Wang, S.; Tian, Q. Mars: A video benchmark for large-scale person re-identification. In Computer Vision—ECCV 2016; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; Volume 9910, pp. 868–884. [Google Scholar]

- Ikeuchi, M.; Oishi, K.; Noguchi, H.; Hayashi, S.; Ikuta, K. Soft tapered stencil mask for combinatorial 3d cluster formation of stem cells. In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Miniaturized Systems for Chemistry and Life Sciences, Groningen, The Netherlands, 3–7 October 2010; Volume 1, pp. 641–643. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, A.; Qin, Y.; Wang, B.; Chen, X.Q.; Jia, L.M. An elastic expandable fault diagnosis method of three-phase motors using continual learning for class-added sample accumulations. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2023, 70, 7896–7905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, C.F.S.; Xiao, Y. Resource-efficient continual learning for sensor-based human activity recognition. ACM Trans. Embed. Comput. Syst. 2022, 21, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Mohamed, M.; Yuriko, E.; Kawagoe, Y.; Kawamura, K.; Ikeuchi, M. AI-Based Augmented Reality Microscope for Real-Time Sperm Detection and Tracking in Micro-TESE. Bioengineering 2026, 13, 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering13010102

Mohamed M, Yuriko E, Kawagoe Y, Kawamura K, Ikeuchi M. AI-Based Augmented Reality Microscope for Real-Time Sperm Detection and Tracking in Micro-TESE. Bioengineering. 2026; 13(1):102. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering13010102

Chicago/Turabian StyleMohamed, Mahmoud, Ezaki Yuriko, Yuta Kawagoe, Kazuhiro Kawamura, and Masashi Ikeuchi. 2026. "AI-Based Augmented Reality Microscope for Real-Time Sperm Detection and Tracking in Micro-TESE" Bioengineering 13, no. 1: 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering13010102

APA StyleMohamed, M., Yuriko, E., Kawagoe, Y., Kawamura, K., & Ikeuchi, M. (2026). AI-Based Augmented Reality Microscope for Real-Time Sperm Detection and Tracking in Micro-TESE. Bioengineering, 13(1), 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering13010102