Corrections of Dental Anomalies in the Maxillary Incisors and Their Influence on Perceived Smile Esthetics: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Rationale

3. Objective

3.1. Choice of Anomalies

3.2. Prevalence

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Protocol and Registration

4.2. Eligibility Criteria

4.3. Information Sources

4.4. Search Strategy

4.4.1. Search 1 (Restorative Restoration)

Pubmed

Google Scholar and Cochrane Library

Embase

Scopus

4.4.2. Search 2 (Esthetic Dentistry)

Pubmed

Google Scholar and Cochrane Library

Embase

Scopus

4.5. Selection Process

4.6. Data Items and Data Collection Process

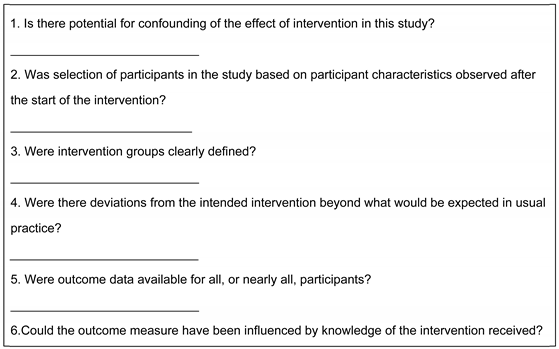

4.7. Study Risk of Bias Assessment

4.8. Synthesis Methods and Effect Measures

5. Results

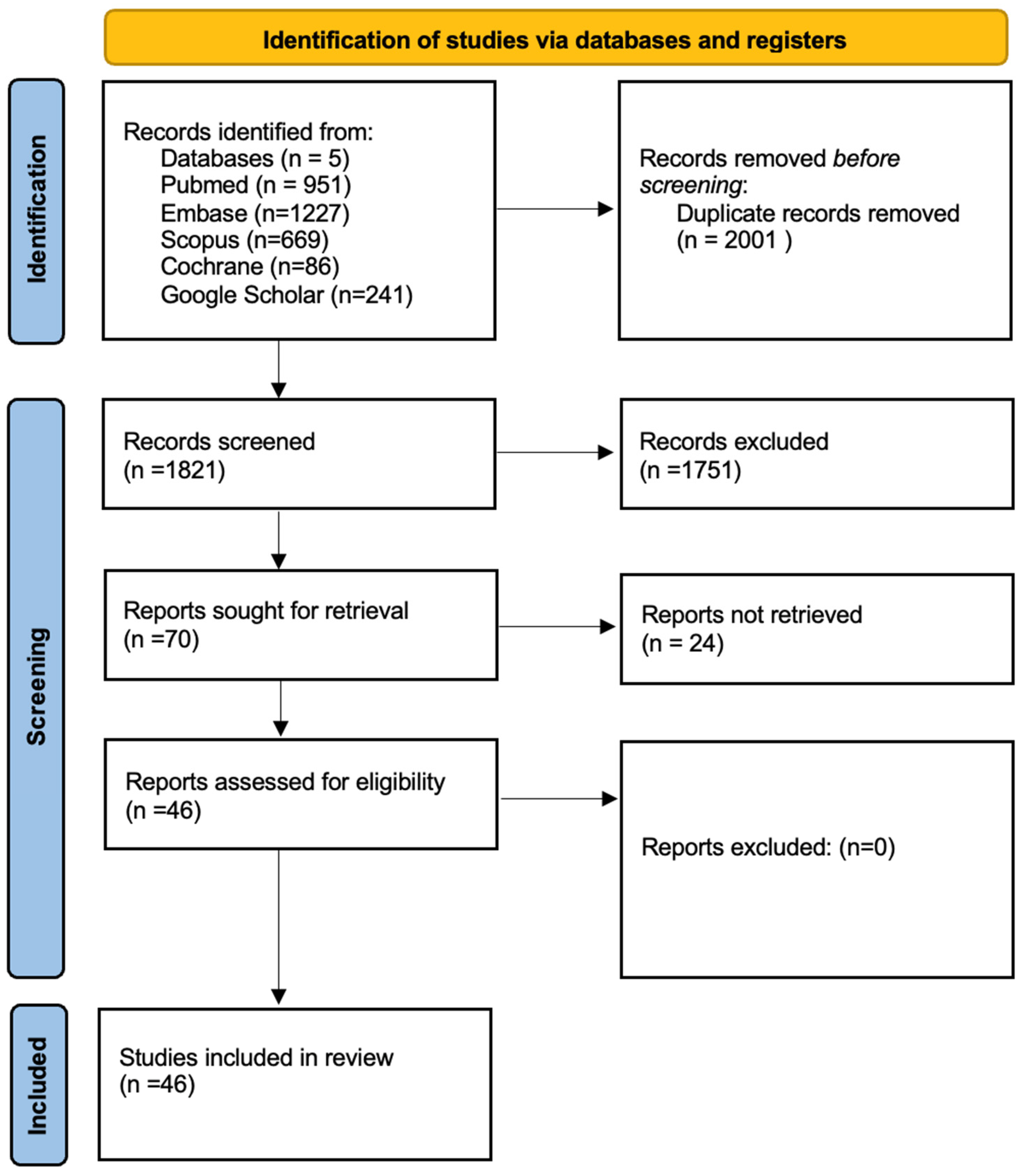

5.1. Study Selection

5.2. Study Characteristics

5.3. Results of Individual Studies

6. Discussion

6.1. Summary of Evidence

6.1.1. Amelogenesis Imperfect and Dentinogenesis Imperfecta

6.1.2. Conoid Teeth

6.1.3. Hypodontia

6.1.4. Microdontia and Macrodontia

6.1.5. Peg Laterals

6.1.6. Perception

6.1.7. Maxillary Lateral Incisor Agenesis

6.1.8. Talon Cusp and Geminated Teeth

6.2. Limitations

6.3. Future Considerations

6.4. Clinical Implications

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Davis, L.G.; Ashworth, P.D.; Spriggs, L.S. Psychological effects of aesthetic dental treatment. J. Dent. 1998, 26, 547–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johal, A.; Huang, Y.; Toledano, S. Hypodontia and its impact on a young person’s quality of life, esthetics, and self-esteem. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2022, 161, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oxford, L. Oxford English Dictionary, s.v. “anomalous (adj.)”. September 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benito, P.; Trushkowsky, R.; Magid, K.; David, S. Fiber-Reinforced Framework in Conjunction with Porcelain Veneers for the Esthetic Replacement of a Congenitally Missing Maxillary Lateral Incisor: A Case Study. Oper. Dent. 2012, 37, 576–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kokich, V.O.; Kinzer, G.A. Managing Congenitally Missing Lateral Incisors. Part I: Canine Sub-stitution. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2005, 17, 5–10. [Google Scholar]

- German, D.S.; Chu, S.J.; Furlong, M.L.; Patel, A. Simplifying optimal tooth-size calculations and communications between practitioners. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2016, 150, 1051–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathi, S.; Dhannawat, P.; Gilani, R.; Vishnani, R. A Multidisciplinary Aesthetic Treatment Approach for Peg Lateral of the Maxillary Incisors. Cureus 2022, 14, e29184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pinho, T.; Maciel, P.; Pollmann, C. Developmental disturbances associated with agenesis of the permanent maxillary lateral incisor. Br. Dent.J. 2009, 207, E25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, J.; Bosio, J.A.; Chou, J.-C.; Jiang, S.S. Maxillary lateral incisor agenesis and its relationship to overall tooth size. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2016, 115, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, W.d.A.; Souza-Silva, B.N.; Bernardino, Í.d.M.; Santana, E.S.; de Matos, F.R.; Bittencourt, M.A.V.; Paranhos, L.R. Maxillary incisorroot morphology in patients with nonsyndromic tooth agenesis: A controlled cross-sectional pilot study. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2020, 157, 212–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, D.J.d.S.; Miguel, J.A.M. Association between hypodontia of permanent maxillary lateral incisors and other dental anomalies. Dent. Press. J. Orthod. 2020, 25, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moundouri-Andritsakis, H.; Kourtis, S.G.; Andritsakis, D.P. All-ceramic restorations for complete-mouth rehabilitation in dentinogenesis imperfecta: A case report. Quintessence Int. 2002, 33, 656–660. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rushworth, B. Oxford Handbook of Clinical Dentistry, 7th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2020; pp. 74–75. [Google Scholar]

- Altug-Atac, A.T.; Erdem, D. Prevalence and distribution of dental anomalies in orthodontic patients. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2007, 131, 510–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Ani, A.H.; Antoun, J.S.; Thomson, W.M.; Merriman, T.R.; Farella, M. Hypodontia: An Update on Its Etiology, Classification, and Clinical Management. BioMed Res. Int. 2017, 2017, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levitan, M.E.; Himel, V.T. Dens Evaginatus: Literature Review, Pathophysiology, and Comprehensive Treatment Regimen. J. Endod. 2006, 32, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hülsmann, M. Dens invaginatus: Aetiology, classification, prevalence, diagnosis, and treatment considerations. Int. Endod. J. 1997, 30, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghassem Ansari, R.W. Atlas of Pediatric Oral and Dental Developmental Anomalies, 1st ed.; Wiley Blackwell: Chichester, UK, 2019; pp. 18–19. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Hernán, M.A.; Reeves, B.C.; Savović, J.; Berkman, N.D.; Viswanathan, M.; Henry, D.; Altman, D.G.; Ansari, M.T.; Boutron, I.; et al. ROBINS-I: A tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ 2016, 355, i4919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laverty, D.P.; Thomas, M.B. The prosthodontic pathway for patients with anomalies affecting tooth structure. Dent. Update 2016, 43, 356–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nathwani, N.S.; Kelleher, M. Minimally Destructive Management of Amelogenesis Imperfecta and Hypodontia with Bleaching and Bonding. Dent. Update 2010, 37, 170–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büchi, D.; Fehmer, V.; Sailer, I.; Wolleb, K.; Jung, R. Minimally invasive rehabilitation of a patient with amelogenesis imperfecta. Int. J. Esthet. Dent. 2014, 9, 134–145. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pena, C.E.; Viotti, R.G.; Dias, W.R.; Santucci, E.; Rodrigues, J.A.; Reis, A.F. Esthetic rehabilitation of anterior conoid teeth: Comprehensive approach for improved and predictable results. Eur. J. Esthet. Dent. Off. J. Eur. Acad. Esthet. Dent. 2009, 4, 210–224. [Google Scholar]

- Ford, S.; Ashley, M.P. The dental technician as a member of the hypodontia multidisciplinary team, with practical considerations for anterior restoration design. Br. Dent. J. 2023, 235, 498–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waldman, A.B. Smile Design for the Adolescent Patient—Interdisciplinary Management of Anterior Tooth Size Discrepancies. J. Calif. Dent. Assoc. 2008, 36, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes-Rocha, L.; Garcez, J.; Tiritan, M.E.; da Silva, L.F.; Pinho, T. Maxillary lateral incisor agenesis and microdontia: Minimally invasive symmetric and asymmetric esthetic rehabilitation. Rev. Port. Estomatol. Med. Dentária E Cir. Maxilofacial. 2022, 63, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brough, E.; Donaldson, A.N.; Naini, F.B. Canine substitution for missing maxillary lateral incisors: The influence of canine morphology, size, and shade on perceptions of smile attractiveness. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2010, 138, 705.e1–705.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thierens, L.A.M.; Verhoeven, B.; Temmerman, L.; De Pauw, G.A.M. An esthetic evaluation of unilateral canine substitution for a missing maxillary lateral incisor. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2017, 29, 442–449. [Google Scholar]

- Stylianou, A.; Liu, P.; O’Neal, S.J.; Essig, M.E. Restoring Congenitally Missing Maxillary Lateral Incisors Using Zirconia-Based Resin Bonded Prostheses. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2016, 28, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qadri, S.; Parkin, N.A.; Benson, P.E. Space closing versus space opening for bilateral missing upper laterals—Aesthetic judgments of laypeople: A web-based survey. J. Orthod. 2016, 43, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mota, A.; Pinho, T. Esthetic perception of maxillary lateral incisor agenesis treatment by canine mesialization. Int. Orthod. 2016, 14, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinho, T.; Bellot-Arcís, C.; Montiel-Company, J.M.; Neves, M. Esthetic Assessment of the Effect of Gingival Exposure in the Smile of Patients with Unilateral and Bilateral Maxillary Incisor Agenesis. J. Prosthodont. 2015, 24, 366–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lombardo, L.; D′Ercole, A.; Latini, M.C.; Siciliani, G. Optimal parameters for final position of teeth in space closure in case of a missing upper lateral incisor. Prog. Orthod. 2014, 15, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkadhimi, A.; Razaghi, N.; Elder, A.; DiBiase, A.T. Camouflaging the permanent maxillary canine to substitute an absent lateral incisor—Part 1: Assessment and management. Br. Dent. J. 2022, 232, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkadhimi, A.; Razaghi, N.; Elder, A.; DiBiase, A.T. Camouflaging the permanent maxillary canine to substitute an absent lateral incisor—Part 2: Challenges and solutions. Br. Dent. J. 2022, 232, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayner, W.J.; Barber, S.K.; Spencer, R.J. The effect of canine characteristics and symmetry on perceived smile attractiveness when canine teeth are substituted for lateral incisors. J. Orthod. 2015, 42, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, E.A.; Oliveira, D.D.; Araújo, M.T. Diagnostic protocol in cases of congenitally missing maxillary lateral incisors. World J. Orthod. 2006, 7, 376–388. [Google Scholar]

- Ulhaq, A. Dental Factors Influencing Treatment Choice For Maxillary Lateral Incisor Agenesis: A Retrospective Study. Eur. J. Prosthodont. Restor. Dent. 2019, 27, 182–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priest, G. The treatment dilemma of missing maxillary lateral incisors-Part I: Canine substitution and resin-bonded fixed dental prostheses. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2019, 31, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De-Marchi, L.M.; Pini NI, P.; Ramos, A.L.; Pascotto, R.C. Smile attractiveness of patients treated for congenitally missing maxillary lateral incisors as rated by dentists, laypersons, and the patients themselves. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2014, 112, 540–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pini, N.P.; De-Marchi, L.M.; Gribel, B.F.; Pascotto, R.C. Digital Analysis of Anterior Dental Esthetic Parameters in Patients with Bilateral Maxillary Lateral Incisor Agenesis. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2013, 25, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinzer, G.A.; Kokich, V.O., Jr. Managing Congenitally Missing Lateral Incisors. Part II: Tooth-Supported Restorations. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. Off. Publ. Am. Acad. Esthet. Dent. 2005, 17, 76–84. [Google Scholar]

- Dolan, S.; Calvert, G.; Crane, L.; Savarrio, L.; PAshley, M. Restorative dentistry clinical decision-making for hypodontia: Peg and missing lateral incisor teeth. Br. Dent. J. 2023, 235, 471–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omeish, N.; Nassif, A.; Feghali, S.; Vi-Fane, B.; Bosco, J. Esthetic and functional rehabilitation of peg-shaped maxillary lateral incisors: Practical recommendations. Clin. Case Rep. 2022, 10, e05507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izgi, A.D.; Ayna, E. Direct restorative treatment of peg-shaped maxillary lateral incisors with resin composite: A clinical report. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2005, 93, 526–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saatwika, L.; Anuradha, B.; Mary, P.G.; Subbiya, A. Esthetic correction of peg laterals—A case report. Eur. J. Mol. Clin. Med. 2020, 7, 2515–8260. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes da Cunha, L.; Procopiak Gugelmin, B.; Gaião, U.; Castiglia Gonzaga, C.; Correr, G.M. Tooth movement with elastic separators before ceramic veneer treatment: Rearranging asymmetric diastemas by managing the horizontal distance. Quintessence Int. 2018, 49, 133–137. [Google Scholar]

- Irmaleny, I.; Hidayat, O.T.; Handayani, R.A.P. Componeer as an aesthetic treatment option for anterior teeth: A case report. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayindir, Y.Z.; Zorba, Y.O.; Barutcugil, C. Direct Laminate Veneers with Resin Composites: Two Case Reports with Five-Year Follow-ups. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 2010, 11, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarpelli, A.C.; Reboucas, A.P.S.; Compart, T.; Novaes-Júnior, J.B.; Paiva, S.M.; Pordeus, I.A. Seven-year follow-up of esthetic alternative for the restoration of peg-shaped incisors: A case study of identical twins. Gen. Dent. 2008, 56, 74–77. [Google Scholar]

- Ittipuriphat, I.; Leevailoj, C. Anterior Space Management: Interdisciplinary Concepts. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2013, 25, 16–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, M.; Reddy, R.; Reddy, B.J. Perception differences of altered dental esthetics by dental professionals and laypersons. Indian J. Dent. Res. 2011, 22, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agou, S.H.; Basri, A.A.; Mudhaffer, S.M.; Altarazi, A.T.; A Elhussein, M.; Imam, A.Y. Dimensions of Maxillary Lateral Incisor on the Esthetic Perception of Smile: A Comparative Study of Dental Professionals and the General Population. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 2020, 21, 992–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cracel-Nogueira, F.; Pinho, T. Assessment of the perception of smile esthetics by laypersons, dental students and dental practitioners. Int. Orthod. 2013, 11, 432–444, (English, French). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosa, M.; Olimpo, A.; Fastuca, R.; Caprioglio, A. Perceptions of dental professionals and laypeople to altered dental esthetics in cases with congenitally missing maxillary lateral incisors. Prog. Orthod. 2013, 14, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Martinez Florez, D.; Rinchuse, D.; Zullo, T. Influence of maxillary lateral incisor width ratio on perception of smile esthetics among orthodontists and laypersons. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2021, 33, 510–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukhary SM, N.; Gill, D.S.; Tredwin, C.J.; Moles, D.R. The influence of varying maxillary lateral incisor dimensions on perceived smile aesthetics. Br. Dent. J. 2007, 203, 687–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.P.; Rauniyar, S. Orthodontic Space Closure of a Missing Maxillary Lateral Incisor Followed by Canine Lateralization. Case Rep. Dent. 2020, 2020, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, D.H. A Study of Dentists’ Preferred Maxillary Anterior Tooth Width Proportions: Comparing the Recurring Esthetic Dental Proportion to Other Mathematical and Naturally Occurring Proportions. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2007, 19, 324–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazıcıoğlu, O.; Ulukapı, H. Management of a Facial Talon Cusp on a Maxillary Permanent Central Incisor: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2014, 26, 374–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokich, V.O.; Kokich, V.G.; Kiyak, H.A. Perceptions of dental professionals and laypersons to altered dental esthetics: Asymmetric and symmetric situations. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2006, 130, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengun, A.; Ozer, F. Restoring function and esthetics in a patient with amelogenesis imperfecta: A case report. Quintessence Int. 2002, 33, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sener, S.; Unlu, N.; Basciftci, F.A.; Bozdag, G. Bilateral geminated teeth with talon cusps: A case report. Eur. J. Dent. 2012, 06, 440–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelleher, M. Dental Bleaching. Quintessentials of Dental Practice. In Operative Dentistry, 1st ed.; Quintessence Publishing Co., Ltd.: Batavia, IL, USA, 2007; Volume 6, pp. 40–60. [Google Scholar]

- Seow, W.K. Clinical diagnosis and management strategies of amelogenesis imperfectavariants. Pediatr. Dent. 1993, 15, 384–393. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Magne, P. Bonded Porcelain Restorations in the Anterior Dentition A Biomimetic Approach; Quintessence Publishing Company: Berlin, Germany, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Magne, P.; Magne, M. Use of additive waxup and direct intraoral mock-up for enamel preservation with porcelain laminate veneers. Eur. J. Esthet. Dent. 2006, 1, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Balasubramaniam, G.R. Predictability of resin bonded bridges—A systematic review. Br. Dent. J. 2017, 222, 849–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shillingburg, H.T. Fundamentals of Fixed Prosthodontics. Learning 1997, 10, 40. [Google Scholar]

- Proffit, W.R. Contemporary Orthodontics, 6th ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2007; pp. 564–570. [Google Scholar]

- Lang, N. Lindhe’s Clinical Periodontology and Implant Dentistry; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenstiel, S.F.; Ward, D.H.; Rashid, R.G. Dentists’ preferences of anterior tooth proportion--a web-based study. J. Prosthodont. 2000, 9, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonald, S.; Arkutu, N.; Malik, K.; Gadhia, K.; McKaig, S. Managing the paediatric patient with amelogenesis imperfecta. Br. Dent. J. 2012, 212, 425–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhaliwal, H.; McKaig, S. Dentinogenesis imperfecta--clinical presentation and management. Dent. Update. 2010, 37, 364–366, 369–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yip, H.K.; Smales, R.J. Oral rehabilitation of young adults with amelogenesis imperfecta. Int. J. Prosthodont. 2003, 16, 345–349. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

| Anomaly Type | Name | Etiology | Prevalence | Appearance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| STRUCTURE | Amelogenesis imperfecta | Inherited in an autosomal dominant manner and are caused by mutations in the FAM83H gene. Disturbance during apposition stage of dental development. | 0.43% | -Hypoplastic—enamel may be thin or pitted [13] -Hypocalcified—enamel is dull, opaque white or brown-colored -Hypomaturation—mottled or frosty looking white opacities at incisal third of crown, “snow-capped teeth” appearance. |

| Dentinogenesis imperfecta Type 2 | Changes in the DSPP gene and is inherited autosomal-dominantly. Disturbance during apposition stage of dental development. | 0.0125% | Opalescent brown or blue hue, bulbous crowns. | |

| SIZE | Macrodontia | General enlargement of all teeth can be observed in certain endocrine conditions. It can be linked to a form of localized gigantism due to an excess of growth hormone. Disturbance during the bud stage of dental development. | 0.03% | Anything above average size is considered macrodont -Central incisor 9 mm wide -Lateral incisor 7.5 mm wide |

| Microdontia | Various environmental and genetic factors can cause the tooth to be underdeveloped. Disturbance during the bud stage of dental development. | 1.51% | Teeth that are smaller than normal. It is distinguished by the reduction in the mesiodistal and cervico-incisal diameters (due to coronary alteration or level of the gingival margins) of the dental crown. | |

| Short roots | Various environmental and genetic factors can cause the root to be underdeveloped. Disturbance during bell stage of dental development. | 1.3% | Seen on radiograph as significantly shorter than average. | |

| NUMBER | Supernumerary-mesiodens | Disturbances during the initiation stages of dental development. | 0.36% | Ref. [14] can be conically or tuberculate shaped, more usually seen as a single tooth, not uncommonly as a pair of extra teeth on the palatal side of crowns. |

| Hypodontia-agenesis | The PAX9 gene was frequently linked to a high risk of maxillary lateral incisor agenesis due to genetic familial inheritance. Disturbance during the initiation stage of dental development. | Europe (5.5%) Australia (6.3%) [15] | Missing tooth element. | |

| MORPHOLOGY | Dens evaginatus (talon cusp) | DE arises during the bell stage of tooth development when some of the dental papilla’s inner enamel epithelium and adjacent ectomesenchymal cells proliferate and fold abnormally into the enamel orga’s stellate reticululm. | 0.6% [16] | The morphology of an accessory cusp has been described as an abnormal tubercle or extrusion that protrudes above the neighboring tooth surface. Characterized by enamel covering a dentinal core that typically contains pulp tissue, occasionally with a thin pulp horn. |

| Tooth fusion Double tooth/tooth gemination | The union of two normally separated tooth germs results in fusion (synodontia). One tooth bud attempting to divide into two crowns with a single root canal is known as gemination. During development, tooth buds may fuse or geminate. Disturbance is during the cap stage. | Gemination 0.07% Fusion 0.23% | In contrast to gemination, which produces teeth with a common pulp chamber, fusion produces teeth with distinct pulp chambers that unite at the dentin level. Radiological examination is the best way to differentiate between a fused or geminated tooth. | |

| Dens invaginatus | Arises from the dental papilla folding inward during tooth development [17]. Disturbance during the cap stage of development. | 0.3% | The affected teeth exhibit a deep infolding that may extend deep into the root, beginning at the foramen coecum or the tip of the cusps. | |

| Peg-shaped laterals | Various environmental and genetic factors can cause the tooth to be underdeveloped [13]. Disturbance during the bud stage of dental development. | 1.58% | Conical appearance | |

| Conoid teeth | Various environmental and genetic factors can cause the tooth to be underdeveloped. Disturbance during the bud stage of dental development. | 0.6% [18] | Short clinical crowns often without contact points, known as tapered teeth. |

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria | |

|---|---|---|

| Population/Patient/Problem | Permanent dentition (apart from 3rd molars) Non-syndromic patients Dental anomalies in morphology, structure, size, and number Structure

Number

| Primary or mixed dentition patients Syndromic patients including, but not limited to:

MIH—pediatric cases Fluorosis and hypoplasia -Oligodontia—frequently associated with a syndromic disorder -Anodontia Trauma—dilaceration, subluxation, fracture Any tooth other than the maxillary incisors, except for maxillary canines, when used in canine mesialization as a conservative treatment for MLIA |

| Intervention | Restorative rehabilitation:

Bleaching and microabrasion Crown lengthening procedure | Surgical rehabilitation (implants) Surgical intervention—autotransplantation, impaction, transmigration Endodontic treatment |

| Comparison | Conservative restorative techniques Anomalous vs. non anomalous dentition | Surgical techniques No treatment |

| Outcome | Primary outcome: Based on standardized esthetic indexes such as: Golden ratio Bolton analysis Smile Esthetic Index RED proportion Patients’ own satisfaction Secondary outcome: Quality of life Long term durability of the restorations | Non-quantifiable results |

| Type of Study | Randomized controlled trials Research studies Case reports Case–control studies Retrospective studies Literature reviews | Systematic reviews and meta-analyses Narrative reviews Letters to the editor In vitro studies |

| ||||||||

| + | low risk of bias | |||||||

| - | high risk of bias | |||||||

| x | unclear risk of bias | |||||||

| AMELOGENESIS IMPERFECTA + DENTINOGENESIS IMPERFECTA. | ||||||||

| Laverty, Dominic P [22] | 2016 | - | + | + | + | x | + | x |

| Nathwani, N.S. and Kelleher, M. [23] | 2010 | - | + | + | + | x | + | x |

| Büchi, D. and Fehmer, V. [24] | 2014 | - | + | + | + | x | + | x |

| CONOID TEETH. | ||||||||

| Pena, C.E. and Viotti. [25] | 2009 | - | + | + | + | x | + | x |

| HYPODONTIA. | ||||||||

| Ford, S., Ashley, M.P. [26] | 2023 | - | x | x | + | x | + | x |

| MICRODONTIA + MACRODONTIA. | ||||||||

| Waldman, A.B. [27] | 2008 | - | + | + | - | x | + | x |

| German, D.S. and Chu, S.J. [6] | 2016 | + | x | + | + | x | + | x |

| Lopes-Rocha, L. and Garcez. [28] | 2022 | - | + | - | + | + | + | x |

| MAXILLARY LATERAL INCISOR AGENESIS (MLIA). | ||||||||

| Brough E, et al. [29] | 2010 | + | + | x | - | + | x | x |

| Thierens, L.A.M., Pet al. [30] | 2017 | + | - | x | + | - | + | x |

| Stylianou A, et al. [31] | 2016 | + | + | - | - | + | + | x |

| Qadri S, et al. [32] | 2016 | + | + | - | - | + | + | x |

| Mota, A. et al. [33] | 2016 | + | + | - | + | + | + | x |

| Pinho, T. et al. [34] | 2015 | + | + | - | - | + | + | x |

| Lombardo, L. et al. [35] | 2014 | + | + | - | - | + | x | x |

| Alkadhimi, A. et al. [36,37] | 2022 | + | + | - | - | + | + | x |

| Rayner, W.J. et al. [38] | 2015 | + | + | - | - | + | + | x |

| Araújo, E.A. et al. [39] | 2006 | + | + | - | x | + | + | x |

| Ulhaq, A. et al. [40] | 2019 | + | + | - | - | + | + | x |

| Priest, G. [41] | 2019 | + | + | - | - | + | + | x |

| De-Marchi, L.M. et al. [42] | 2014 | + | + | - | - | + | + | x |

| German, D.S. et al. [6] | 2016 | + | + | + | - | + | + | x |

| Lopes-Rocha, L. et al. [28] | 2022 | + | + | - | - | + | - | x |

| Pini, N.P. et al. [43] | 2012 | + | + | - | - | + | + | x |

| Benito, P.P. et al. [4] | 2012 | + | + | - | x | + | + | x |

| Kokich Jr., V.O. et al. [44] | 2005 | + | + | - | - | + | + | x |

| Kokich Jr et al. [5] | 2005 | + | + | - | - | + | + | x |

| PEG-SHAPED LATERAL. | ||||||||

| Rathi S, et al. [7] | 2022 | + | - | - | + | - | x | x |

| Dolan, S. et al. [45] | 2023 | + | + | - | - | + | + | x |

| Omeish, N. et al. Bosco, J. [46] | 2022 | + | - | + | + | - | x | + |

| Izgi, Ayna [47] | 2005 | + | + | - | - | + | + | x |

| Saatwika, et al. [48] | 2020 | + | + | - | - | + | + | x |

| da Cunha, L.F. et al. [49] | 2018 | + | + | - | - | + | + | x |

| Irmaleny, I. et al. [50] | 2024 | + | + | - | - | + | + | x |

| Zorba, Y.O. et al. [51] | 2010 | + | - | - | - | + | + | x |

| Scarpelli, A.C. et al. [52] | 2008 | + | + | - | + | - | + | x |

| Ittipuriphat, I. et al. [53] | 2013 | + | + | - | - | + | + | x |

| PERCEPTION. | ||||||||

| Thomas M, et al. [54] | 2011 | + | + | - | - | + | + | x |

| Agou SH, et al. [55] | 2020 | + | + | - | - | + | + | x |

| Cracel-Nogueira F, Pinho T. [56] | 2013 | + | + | - | - | + | + | - |

| Rosa, Olimpo. [57] | 2013 | + | + | + | - | - | + | x |

| Kokich, et al. [5] | 2006 | + | + | - | - | + | + | + |

| De-Marchi, L.M. et al. [42] | 2014 | + | + | - | - | - | + | + |

| Mota, Pinho [33] | 2015 | + | + | - | + | + | - | x |

| Florez, Rinchuse. [58] | 2019 | + | + | - | - | + | + | x |

| Parkin, Benson [32] | 2016 | + | + | - | - | + | + | x |

| Bukhary S.M., et al. [59] | 2007 | + | + | - | + | + | - | - |

| Souza RA, et al. [10] | 2017 | + | + | - | - | + | + | x |

| Amelogenesis Imperfecta and Dentinogenesis Imperfecta. | |||||||

| Title | Year | Authors | Study Design | Population | Intervention | Comparison | Outcome |

| The prosthodontic pathway for patients with anomalies affecting tooth structure | 2016 | Laverty, Dominic P and Thomas, Matthew BM [22] | Clinical article | N/A | Patients with AI and DI frequently have veneers placed on their anterior teeth. They permit good esthetics whilst being relatively conservative of tooth tissue in comparison to crowns. | Various restorative options—resin bonding vs. veneers vs. crowns and onlays. | Although adhesion to teeth affected by AI and DI is less predictable, minimal preparation is necessary to preserve as much tooth tissue as possible. |

| Minimally destructive management of amelogenesis imperfecta and hypodontia with bleaching and bonding. | 2010 | Nathwani, N.S. and Kelleher, M. [23] | Case report | 20-year-old female | Prosthodontics for MILA—cantilever on canines in this case, plus composite bonding to maintain spaces and stop mesial drifting. | Bleaching, gingivectomy, composite bonding and cantilever bridges on canines were used instead of the more invasive traditional veneer or bridge placement | Patient very pleased with final outcome |

| Minimally invasive rehabilitation of a patient with amelogenesis imperfecta. | 2014 | Büchi, D. and Fehmer, V. and Sailer, I. and Wolleb, K. and Jung, R. [24] | Case report | 27-year-old female | Crown lengthening on to prep for veneers later. At home bleaching for. Period of 2 weeks followed up by microabrasion. Veneer placement to alter position and shape of teeth—silicon key as a guide for prep before fabrication. | Veneers to cover the extensive staining—bleaching and microabrasion improved the underlying tooth color, but bonding would not have been as effective in this case. | Patient was happy with the final treatment outcome. At a follow-up visit 18 months post-insertion, all the veneers looked well integrated without any discoloration of the margin, or chipping or fractures of the ceramic |

| Conoid Teeth. | |||||||

| Title | Year | Authors | Study Design | Population | Intervention | Comparison | Outcome |

| Esthetic rehabilitation of anterior conoid teeth: comprehensive approach for improved and predictable results. | 2009 | Pena, C.E. and Viotti, R.G. and Dias, W.R. and Santucci, E. and Rodrigues, J.A. and Reis, A.F. [25] | Case report | 22-year-old female | Gingivectomy of laterals, bleaching, silicone index and mockup. Luting, laminate veneers for laterals and composite bonding for central incisors. | Conservative veneer prep allows its translucency to render a natural appearance vs. Ultraconservative veneer prep preserves the available enamel for bonding, thus increasing the prognosis for long-term bonding success. | Patient was satisfied with outcome |

| Hypodontia. | |||||||

| Title | Year | Authors | Study Design | Population | Intervention | Comparison | Outcome |

| The dental technician as a member of the hypodontia multidisciplinary team, with practical considerations for anterior restoration design | 2023 | Ford, S., Ashley, M.P. [26] | Discussion article | N/A—hypodontia patients | Design of a resin-bonded bridge with bridge wing design, taking into account the incisal edge and the occlusal surface and also the abutment of choice. | Optimal abutment tooth: orthodontically repositioned canines are prone to rotation during relapse. As a result, a cantilever lateral incisor bridge attached to a canine may relapse. An alternative is to replace both lateral incisor teeth with a single restoration using a bridge that is appropriately crafted from both maxillary central incisors. | Replacing the missing anterior requires clinicians and dental technicians to collaborate. Ideal tooth placement and the creation of space between natural teeth can be made possible by mutual understanding, allowing restorations to be used to produce acceptable functional and esthetic results. |

| Microdontia and Macrodontia. | |||||||

| Title | Year | Authors | Study Design | Population | Intervention | Comparison | Outcome |

| Smile design for the adolescent patient--interdisciplinary management of anterior tooth size discrepancies | 2008 | Waldman, A.B. [27] | Discussion Article | Adolescents | Interdisciplinary diagnosis and treatment plan. Orthodontic space management. Vertical management of gingival margins 4) Restorative phase. 5) Finishing. | These clinical principles for treating adolescent patients with a significant TSD. Bolton analysis to determine tooth size discrepancies. | The most important factors in clinical planning: tooth size, tooth shape, tooth proportions, occlusion, incisal edge position, gingival margin position, restorative material, treatment timing and sequence. |

| Simplifying optimal tooth-size calculations and communications between practitioners | 2016 | German, D.S. and Chu, S.J. and Furlong, M.L. and Patel, A. [6] | Discussion Article | Orthodontic patient | Anomalous incisors can be restored early during orthodontic correction. At least 2 mm is created around the lateral incisors by the orthodontist. The brackets are taken out, the dentist resizes and shapes them to the patient’s specifications, the brackets are put back in, and the gaps are sealed. | New methods vs. Bolton Analysis—both have some discrepancies. In contrast to the normal anterior Bolton ratio of 77.2 percent, the tooth widths in this example yield a total tooth mass of 45 mm for the maxillary anterior teeth; 36 mm divided by 45 mm yields an anterior Bolton ratio of 80 percent. | Since the mandibular central incisor is the least variable of the 12 anterior teeth, its width can be used to determine the ideal sizes of the other teeth when several of them are abnormal, missing, or not of the proper size. As a result, the ideal maxillary incisor widths can be determined by measuring their width. |

| Maxillary lateral incisor agenesis and microdontia: Minimally invasive symmetric and asymmetric esthetic rehabilitation | 2022 | Lopes-Rocha, L. and Garcez, J. and Tiritan, M.E. and da Silva, L.F.M. and Pinho, T. [28] | Case Report | Adolescent orthodontic patients | Pretreatment planning using Bolton analysis and golden proportion. Bleaching, enameloplasty, and bonding with composite resin can enhance esthetics and functions following orthodontic space closure. | Following orthodontic treatment for the six anterior upper and lower teeth, an analysis of tooth movement using golden proportion and Bolton’s anterior was conducted prior to treatment planning. | An alternative method for figuring out how much room to make for an MLI is the Bolton analysis. The most efficient and esthetically pleasing results for patients are generally acknowledged to be obtained through a diagnostic wax-up and a smile simulation. The proportion in gold (i.e., E.) For figuring out the MLI width, a fixed ratio of 1.618:1 can serve as a framework. |

| Peg Laterals. | |||||||

| Title | Year | Authors | Study Design | Population | Intervention | Comparison | Outcome |

| A Multidisciplinary Aesthetic Treatment Approach for Peg Lateral of the Maxillary Incisors | 2022 | Rathi S, Dhannawat P, Gilani R, Vishnani R. [7] | Case report | 22 yr old female | Frenectomy and midline diiastema closure, space created for peg laterals’ build up in composite bonding. | Treatment options; canine mesialization and recontouring. Replacement fixed partial dentures (FPDs), restoration peg lateral incisors. | A multidisciplinary approach in treatment results in enhances a conservative yet very esthetic finished result. |

| Restorative dentistry clinical decision-making for hypodontia: peg and missing lateral incisor teeth | 2023 | Dolan, S. and Calvert, G. and Crane, L. and Savarrio, L. and P Ashley, M. [45] | Clinical article | N/A | Multidisciplinary; MLIA—space closure or opening. PEG—removal or retaining tooth with composite build up. | Space closure vs. opening in MLIA. Removal or retain peg lateral. | No mention |

| Esthetic and functional rehabilitation of peg-shaped maxillary lateral incisors: Practical recommendations | 2022 | Omeish, N. and Nassif, A. and Feghali, S. and Vi-Fane, B. and Bosco, J. [46] | Clinical case | N/A | Multidisciplinary: orthodontic movement and veneer on one peg lateral. Composite bonding on the other. Veneer on the left lateral due to its shape and the high interproximal space to fill. Direct composite on right lateral due to low interproximal space. | Veneer versus composite bonding. Digital Smile Design and mockup to help with orthodontic finishing and help with tooth preparation. | Digital Smile Design to determine the lateral incisor dimensions—during the orthodontic finishing phase. To facilitate the movement of the peg-shaped affected teeth, DSD can be transformed into a mock-up |

| Direct restorative treatment of peg-shaped maxillary lateral incisors with resin composite: A clinical report | 2005 | Ayca Deniz Izgi and Emrah Ayna [47] | Clinical report | 4 adult patients | Direct resin composite laminate veneers | Resin composite bonding versus ceramic restorations. | Resin composite shown to be more conservative of the underlying dentition, less brittle as a material and less abrasive for the opposing dentition in comparison to its porcelain counterparts. |

| Esthetic correction of peg laterals—A case report | 2020 | Saatwika, L. and Anuradha, B. and Gold Pearlin Mary [48] | Case report | 19-year-old female | Ortho treatment for midline diastema, correction of peg laterals using direct composites and putty technique | Advantages and disadvantages of composite bonding. | Good esthetics and good periodontal outcome. |

| Tooth movement with elastic separators before ceramic veneer treatment: Rearranging asymmetric diastemas by managing the horizontal distance | 2018 | da Cunha, L.F. and Gugelmin, B.P. and Gaião, U. and Gonzaga, C.C. and Correr, G.M. [49] | Case reports | 18-year-old female | Space creation with interdental elastics orthodontic movement to increase the proximal spaces and redistribute the diastemas before closing with minimally invasive ceramic veneers. | Redistribution of spaces before veneer placement or not. | Revaluation of patients smile after 10 months after cementation—anterior tooth proportion, periodontal health and smile arc were all optimal. |

| Componeer as an aesthetic treatment option for anterior teeth: a case report | 2024 | Irmaleny, I. and Hidayat, O.T. and Handayani, R.A.P. [50] | Case report | 32-year-old female | Use of componeer Digital Smile Design, wax-up and mockup used to determine ideal proportions. | Ceramic veneers versus composite | In order to attain a golden proportion, the final restoration results demonstrate an increase in each tooth’s height and width. |

| Direct laminate veneers with resin composites: two case reports with five-year follow-ups. | 2010 | Zorba, Y.O. and Bayindir, Y.Z. and Barutcugil, C. [51] | Case report | 15-year-old female | Direct laminate resin-based composite veneers to improve esthetics. | Veneer vs. composite bonding. DSD and mockup help with orthodontic finishing and tooth preparation. | Very satisfied patient. |

| Seven-year follow-up of esthetic alternative for the restoration of peg-shaped incisors | 2008 | Scarpelli, A.C. and Reboucas, A.P.S. and Compart, T. [52] | Case report | 14-year-old identical twins | Direct composite bonding of the right peg lateral in both twins. | The dimensions of the maxillary left lateral incisor served as reference. | Very satisfied patients. |

| Anterior space management: Interdisciplinary concepts | 2013 | Ittipuriphat, I. and Leevailoj, C. [53] | Discussion | N/A | CLP, minor tooth movement and bleaching prior to restoration. Composite bonding corrected anterior spacing. Final restoration of ceramic veneers on the lateral peg-shaped incisors. | Golden proportion vs. RED proportion. | RED proportion show need for gingival margin alteration and orthodontic movement. Tooth spacing analyzed based on the (RED) proportion. |

| Perception. | |||||||

| Title | Year | Authors | Study Design | Population | Intervention | Comparison | Outcome |

| Perception differences of altered dental esthetics by dental professionals and laypersons | 2011 | Thomas M, Reddy R, Reddy BJ. [54] | Comparative study | Orthodontists vs. general dentists vs. laypersons | Three images of smiles were altered using a software-imaging program. The alterations involved the crown length, crown width, midline diastema, and the papillary height of the maxillary anterior teeth. These images were then rated. | All three groups could identify a unilateral crown width discrepancy of 2.0 mm. No group considered a small diastema in the midline to be unattractive. In general, people found it less appealing when papillary height was reduced. | When assessing asymmetric crown length discrepancies, orthodontists were more critical than general dentists and laypeople. Asymmetric alterations make teeth more unattractive not only to the dental professionals, but also to laypersons. |

| Dimensions of Maxillary Lateral Incisor on the Esthetic Perception of Smile: A Comparative Study of Dental Professionals and the General Population | 2020 | Agou SH, Basri AA, Mudhaffer SM, Altarazi AT, Elhussein MA, Imam AY. [55] | Comparative study | 156 participants, 36 patients with hypodontia (HP), 54 non-hypodontia patients (NHP), and 30 dentists (D). | Using computer software, two sets of photos were produced with the maxillary incisor dimensions altered. The width of the maxillary lateral incisors was altered in the first set. Only the maxillary lateral incisor length was altered in the second set, while the gingival margins remained unchanged. | The smiles with a lateral incisor to central incisor width proportion of 77 percent, according to 25.0 percent (HP), 40.8 percent (D), and only 4.2 percent of (P), were the most attractive. The smiles with 52.0 percent (HP), 20.8 percent (P), and 49.0 percent (D) were the least popular. | Not all groups were thought to be the most attractive, including the golden proportion. Dentists may have different esthetic opinions than their patients. Not all maxillary lateral incisor width reductions were generally deemed acceptable. |

| Assessment of the perception of smile esthetics by laypersons, dental students and dental practitioners | 2013 | Cracel-Nogueira F, Pinho T. [56] | Comparative study | 292 laypersons, 241 dental students and 101 practitioners | With Adobe Photoshop, a smile’s manipulated elements—the gingival exposure, gingival margin level, crown length, maxillary midline, and inter-incisor diastema—were changed. Visual analogue scale (VAS) responses were gathered and assigned a score between 1 and 10. | The medium smile was regarded as the most esthetic, and high smile line and diastemas the least. Importance of MCI in smiling shown via the preference for asymmetry of the gingival margin at the maxillary lateral incisors (MLI). | Professionals were more critical in their scoring, while laypeople, dental students, and dental professionals all had different opinions about how attractive various modified features were, with the exception of diastemas. |

| Smile attractiveness of patients treated for congenitally MLIA as rated by dentists, laypersons, and the patients themselves | 2014 | De-Marchi, L.M. and Pini, N.I. and Ramos, A.L. and Pascotto, R.C. [42] | Comparative study | 60 patients with MLIA, 20 laypersons, and 20 dentists | Evaluation of smile attractiveness in patients treated with space closure or space opening. | Patients treated with space closure reported higher satisfaction with their smiles compared to those treated with space opening. | Laypersons rated smiles with space closure more attractive than space opening. Dentists had a higher rating for space opening. |

| Influence of maxillary lateral incisor width ratio on perception of smile esthetics among orthodontists and laypersons | 2022 | Daniela Martinez Florez [58] | Cross-sectional study | 283 laypersons and 83 orthodontists | A smile showing the lips and gingival margins was selected. The smile was standardized for maxillary central incisor width proportions and ideally perceived smile esthetics. In symmetrical increments of the central incisor ratio, the maxillary lateral incisor width was adjusted from 4:10 to 8:10. | Evaluated the perception of smile esthetics with different width ratios of maxillary lateral incisors among laypeople and orthodontists. | For orthodontists, the most attractive width ratio was 5.7:10, conversely for was 8:10, although laypersons ranked all ratios very similarly. The width ratio of 4:10 was ranked lowest by both groups. When evaluating esthetics, orthodontists were more critical. |

| Space closing versus space opening for bilateral missing upper laterals—aesthetic judgments of laypeople: a web-based survey | 2016 | Parkin, Benson [32] | Web-based survey | 959 participants including staff and students at the University of Sheffield | Evaluation of 10 images of space closing (OSC) versus prosthetic replacement (PR) in images of patients with missing upper lateral incisors. Using a 5-point Likert scale. | The mean rating for OSC images was 3 points 34 out of 5, which is higher than the mean rating for PR images, which is 3 points 14 out of 5. Three out of four paired images were preferred by both males and females as OSC images. | The general public found space closing more appealing than space opening. Higher ratings of attractiveness were typically given by female and staff judges. |

| The influence of varying maxillary lateral incisor dimensions on perceived smile aesthetics | 2007 | Bukhary SM, Gill DS, Tredwin CJ, Moles DR. [59] | Clinical study | 41 hypodontia patients, 46 non-hypodontia ‘control’ patients, and 30 dentists. | Alteration of maxillary lateral incisor dimensions in images. Initially, the maxillary lateral incisors’ width in relation to the central incisor was changed. In a second group, the lateral incisor’s length was changed in increments of 0–5 mm. | Laypersons were more tolerant of variations in width ratios. All groups preferred the lateral to central width proportions of 67 percent and 72 percent, respectively. It was found that the most common maxillary lateral incisor length was 1–1.5 mm shorter than the central. | The golden proportion is a range rather than a single value. The 67% lateral-to-central width proportion followed by the 72% width proportion were most preferred. Very long + very short lateral incisors were thought to be the least attractive. Patients with hypodontia favored longer lateral incisors. |

| Esthetic perception of maxillary lateral incisor agenesis treatment by canine mesialization | 2015 | Antonino Mota, Teresa Pinho [33] | Observational study | 654 participants including 303 laypersons, 215 general dentists, 55 prosthodontists, and 82 orthodontists. | Nine images were digitally modified from the same frontal intraoral photograph to show various treatment options for space closure in MLIA for comparison along with a questionnaire. | The MLIA restoration perceived to be most attractive showed unilateral dental and gingival reshaping. Dental and gingival reshaping was considered the most attractive whereas unmodified mesialization was considered the least attractive. | Regarding SC treatments, all groups regarded simple dental reshaping of the canine to be attractive, only the dental professionals considered gingival and crown reshaping to be the most esthetic. |

| Perceptions of dental professionals and laypeople to altered dental esthetics in cases with congenitally missing maxillary lateral incisors | 2013 | Marco Rosa, Alessia Olimpo, Rosamaria Fastuca and Alberto Caprioglio [57] | Observational study | 160 participants including laypeople, adult orthodontic patients, general dentists, and orthodontists. | Alterations of dental esthetics in images (crown length, crown width, midline diastema, and papillary height) using software-imaging program. Professionals and laypeople were found to perceive smiles significantly differently. | Asymmetric alterations were deemed unattractive by both groups. Dental tipping and a noticeable diastema in the arch were discordant features that no one liked to see in a smile. Simulations associated with SC orthodontic treatment were ranked as the most attractive smile and significantly ranked higher by dental professionals than patients and laypeople. | Orthodontists were more critical of asymmetric crown length discrepancies. All groups identified a 2.0 mm crown-width discrepancy. Midline diastema was not rated unattractive. Papillary height reduction was generally rated less attractive. Treatment, absence of diastema, and symmetry were the most accepted characteristics by all. |

| Perceptions of dental professionals and laypersons to altered dental esthetics: Asymmetric and symmetric situations | 2006 | Vincent O. Kokich, Vincent G. Kokich, and H. Asuman Kiyak [63] | Observational study | General dentists, orthodontists, and laypersons. | A software imaging program was used to modify seven pictures of women’s smiles. The alterations involved crown length, crown width, midline diastema, papilla height, and gingiva-to-lip relationship of the maxillary anterior teeth. These altered images were rated using a visual analog scale. | Orthodontists were more critical than others when evaluating asymmetric crown length discrepancies. A unilateral crown width discrepancy of 2 points 0 mm was found by all groups. No group found a small midline diastema to be unattractive. Bilateral alteration was deemed more appealing than unilateral papillary height reduction. | In general, asymmetric alterations make teeth more unattractive to not only dental professionals but also the lay public. Symmetric alterations might appear unattractive to dental professionals, but the lay group often did not recognize some symmetric alterations. |

| Perception of attractiveness of missing maxillary lateral incisors replaced by canines | 2018 | Souza RA, Alves GN, Mattos JM, Coqueiro RDS, Pithon MM, Paiva JB. [10] | Observational study | 150 laypersons and 100 dentists and dental students | A 20-year-old woman’s smiling front view extraoral photo was digitally modified to mimic agenesis and its treatment by shifting, bleaching, or reshaping the gingival and canine contours. | While dentists thought that MLIA with canine repositioning and reshaping was the least attractive, students and laypeople thought that MLIA with canine repositioning, gingival contour, bleaching, and reshaping was the worst. | Dentists and students were more likely to accept treatment approaches that involved altering the gingival contour than laypeople, who preferred approaches that merely involved reshaping. |

| Maxillary Lateral Incisor Agenesis. | |||||||

| Title | Year | Authors | Study Design | Population | Intervention | Comparison | Outcome |

| Canine substitution for missing maxillary lateral incisors: the influence of canine morphology, size, and shade on perceptions of smile attractiveness | 2010 | Brough E, Donaldson AN, Naini FB. [29] | Observational study | 120 participants (40 orthodontists, 40 dentists, and 40 laypeople) | A smiling photograph of a hypodontia patient who had OSC with maxillary canines replacing the lateral incisors. Image digitally altered the canine gingival height, crown tip height, canine width, and canine shade. | The most appealing canine gingival height was 0–5 mm below the maxillary central incisor’s gingival margin. It was thought that pointed canines, wider canines, and taller canine tips were unsightly. | Dark canines were ranked least attractive by all groups, Natural shades were preferred by dentists and brighter shades by orthodontists and laypeople. Narrow canine crowns frequently were ranked as most attractive. |

| An esthetic evaluation of unilateral canine substitution for a missing maxillary lateral incisor | 2017 | Thierens LAM, Verhoeven B, Temmerman L, De Pauw GAM. [30] | Observational study | 174 examiners of orthodontists, periodontists, dentists, and laypeople | By modifying a photograph from the standard, the following parameters were investigated: (1) width, (2) color, (3) gingival margin height, (4) crown tip morphology of the substituted canine, and (5) gingival margin height of the neighboring first premolar. | Overall, a darker canine color and a more pronounced canine tip morphology were significantly ranked as most unattractive (p < 0.05). The gingival height of the neighboring premolar was ranked as least unattractive by all groups of examiners. | Darker canine color and a pronounced tip morphology of a substituted canine are rated as the most unattractive by dental professionals and laypeople. |

| Restoring Congenitally Missing Maxillary Lateral Incisors Using Zirconia-Based Resin Bonded Prostheses | 2016 | Stylianou A, Liu PR, O’Neal SJ, Essig ME. [31] | Clinical report | 17-year-old patient | For a young patient with very high esthetic standards, zirconia-based resin-bonded fixed partial dentures (RBFPDs) were chosen as a practical and conservative treatment option. After being digitally designed, the bilateral-winged zirconia frameworks were milled with (CAD/CAM)-controlled milling machine. | Tooth preparation design and subsequent RBFDP framework design are fundamental for the mechanical retention and strength of the prosthesis. An increased frequency of adhesive debonding has been recorded for non-retentive prepared RBFDP retainers. | Completion of the treatment resulted in a functional and esthetic successful outcome and a 17-month follow-up presented uneventful. Esthetic expectations and potential ongoing growth of the patient must be thoroughly considered. |

| Esthetic Assessment of the Effect of Gingival Exposure in the Smile of Patients with Unilateral and Bilateral Maxillary Incisor Agenesis | 2015 | Pinho, T. and Bellot-Arcís, C. and Montiel-Company, J.M. and Neves, M. [34] | Observational study | 381 people (80 orthodontists, 181 general dentists, 120 laypersons) | In four cases, patients were asked to score the smiles’ attractiveness both before and after treatment, including two cases with bilateral MLIA and two cases with unilateral MLIA and contralateral microdontia. A computer was used to modify the buccal photo in each instance, applying standard lips to produce high, medium, and low smiles. | Photos of people with medium smiles scored higher than those with high or low smiles in both the pre- and post-treatment cases, and the differences were substantial. In all cases, orthodontists were the least tolerant evaluation group (assigning lowest scores), followed by general dentists. | The medium-height smile was considered to be more Symmetrical treatments scored higher than asymmetrical treatments. Gingival exposure had a significant influence on the esthetic perception of smiles in post-treatment cases. |

| Optimal parameters for final position of teeth in space closure in case of a missing upper lateral incisor | 2014 | Lombardo, L. and D′Ercole, A. and Latini, M.C. and Siciliani, G. [35] | Case–control | 30 patients with MLIA | Space closure setup in the upper lateral incisor region was carried out in 30 individuals with agenesis in this specific tooth. The tip, torque, and in–out measurements were taken and contrasted with the data from earlier researchers. | With the exception of the first premolars, which need a larger tip, and the first molars, which need a smaller tip, the tip values in the upper dentition were similar to those reported by Andrews (Am J Orthod 62 (3):296–309, 1972). | An important suggestion, seen in other studies, is extruding the canine and intruding the first premolar in order to obtain ideal gingival architecture. |

| Camouflaging the permanent maxillary canine to substitute an absent lateral incisor—part 2: challenges and solutions | 2022 | Alkadhimi, A. and Razaghi, N. and Elder, A. and DiBiase, A.T. [37] | Clinical article | N/A | Some of the common problems in canine camouflage cases are discussed, along with potential fixes. | Bolton’s analysis is used to identify any disparity in tooth size. Gingival discrepancy: Intrusion and extrusion of the involved teeth, as well as a higher gingival margin, can change the gingival contour. | In general, the golden proportion concept of esthetics can serve as a helpful guide to attain ideal dimensions and symmetry. However, it is important to consider the patient’s perspective and acknowledge that there may be genetic, ethnic, and cultural differences in determining what is esthetically pleasing. |

| The effect of canine characteristics and symmetry on perceived smile attractiveness when canine teeth are substituted for lateral incisors | 2015 | Rayner, W.J. and Barber, S.K. and Spencer, R.J. [38] | Prospective cross-sectional study | 90 participants (30 orthodontists, 30 dentists and 30 laypeople) | Different dentitions were displayed using a picture of a smiling woman. There was a control picture with the “ideal” smile, and six more pictures that replaced the maxillary lateral incisors with canine teeth of different sizes, either unilaterally or bilaterally. | Orthodontists and GDP rated smiles with canine substitution for lateral incisor agenesis to be significantly less attractive than an ideal smile unless the substituted canine teeth approximated the lateral incisor in terms of size, shape, color, and gingival margin. Regardless of the canine tooth characteristics, laypeople did not find the same smiles to be noticeably more or less attractive than an ideal smile. All groups did not find smiles with unilateral canine substitution to be noticeably less attractive than those with bilateral canine substitution. | Dental professionals were significantly more perceptive than lay people to the deviation from ideal smile esthetics when canine teeth were substituted for lateral incisors. Orthodontists, general practitioners, and laypeople did not find smiles with a unilaterally replaced canine tooth inherently less attractive than those with a bilaterally substituted canine tooth. |

| Diagnostic protocol in cases of congenitally missing maxillary lateral incisors. | 2006 | Araújo, E.A. and Oliveira, D.D. and Araújo, M.T. [38] | Literature Review | N/A | Discussion of clinical variables to be considered -canine position, color, functional occlusion and gingival height. | Canine color—the presence of color difference has a big impact on perception. Functional occlusion—can be obtained with lateral group function after space closure, as opposed to canine. Gingival height—Ideal anterior gingival architecture has the central incisor and canine margins at the same level, while the lateral incisor gingival contour is approximately 1 mm more incisal. | Canine position and its root angulation may be a complicating factor when the clinician decides to open space for a prosthesis. In patients with congenital MLIA the canines frequently show a mesial pattern of eruption. Such a condition favors using the canine as a substitute for the lateral incisor. |

| Dental Factors Influencing Treatment Choice For Maxillary Lateral Incisor Agenesis: A Retrospective Study | 2019 | Ulhaq, A. and Fee, P. and Cresta, M. and Turner, S. and Dutta, A. [40] | Retrospective study | 44 MLIA patients previously treated | Baseline data consisted of patient records, pre-treatment orthodontic study casts and clinical photographs | Space closing versus space opening. Space opening importantly, the amount of bone that is available at the lateral incisor site—often found to be deficient. Space closing—surveys have shown that patient who have space closure and canine recontouring are perceived as having the best esthetic results. | Orthodontic space opening for MLIA is linked to the maxillary arch’s sufficient space. |

| The treatment dilemma of missing maxillary lateral incisors-Part I: Canine substitution and resin-bonded fixed dental prostheses | 2019 | Priest, G. [41] | Review article | N/A | Discussion of treatment options for MLIA Canine substitution and resin-bonded fixed dental prosthesis. | Canine substitution versus resin-bonded bridge. Multiple studies have shown canine substitution to be preferable esthetically compared to prosthodotic interventions, as well as preferable outcomes in terms of periodontal health. A RBFDP can be removed whenever it is no longer required with little to no modification of the adjacent teeth, and can be rebonded or remade again with minimal adverse effects on the supporting teeth. | Available data indicates that canine substitution and RBFDPs have demonstrated successful results and patient satisfaction. Dental teams should inform patients about the alternatives and mutually agree on the treatment solution tailored for each patient that provides the best potential for long-term esthetics and function. |

| Simplifying optimal tooth-size calculations and communications between practitioners | 2016 | German, D.S. and Chu, S.J. and Furlong, M.L. and Patel, A. [6] | Clinical article | N/A | A simple formula to determine optimal tooth sizes, along with an esthetic guide worksheet to use with collaborating dentists. | This method uses the mandibular incisors as a reference for size, especially in the anomalous dentition. The width of the mandibular central incisor can be used to calculate the ideal sizes of the other, anomalous dentition as it is the least variable tooth among the 12 anterior teeth. | Due to maxillary and mandibular teeth being smaller than normal in patients missing one or both maxillary lateral incisors space created or remaining for the final restorations may be smaller than ideal. Thus, clinicians should plan accordingly. |

| Maxillary lateral incisor agenesis and microdontia: Minimally invasive symmetric and asymmetric esthetic rehabilitation | 2022 | Lopes-Rocha, L. and Garcez, J. and Tiritan, M.E. and da Silva, L.F.M. and Pinho, T. [28] | Clinical study | 40 orthodontic patients treated for MLIA | Casts were made and teeth were measured with a digital caliper at their greatest mesiodistal width and then compared with those of a control group matched for ethnicity, age, and sex. | The maxillary arch had a larger tooth size difference between the control and test groups than the mandibular arch maxillary and mandibular teeth are smaller than normal in patients missing one or both maxillary lateral incisors. | Because maxillary and mandibular teeth are smaller than normal in patients missing one or both maxillary lateral incisors space created or remaining for the final restorations may be smaller than ideal. |

| Fiber-reinforced framework in conjunction with porcelain veneers for the esthetic replacement of a congenital MILA | 2012 | Benito, P.P. and Trushkowsky, R.D. and Magid, K.S. and David, S.B. [4] | Case study | 28-year-old female | For teeth 5–12, porcelain veneers and the congenitally missing upper right lateral incisor were replaced with a metal-free, two-component, resin-bonded Encore bridge. | Comparing the Encore bridge’s less invasive preparation to that of conventional metal ceramic full-coverage fixed partial dentures. | The metal-free RBFPD has proven to be a good substitute for single-tooth replacement in the anterior esthetic zone. |

| Managing congenitally missing lateral incisors. Part I: Canine substitution | 2005 | Kokich Jr., V.O. and Kinzer, G.A. [5] | Review article | N/A | Discussion of the most important parameters to consider for canine substitution, including malocclusion, profile, color, and shape of the canines and lip level. Malocclusion: most suitable for canine substitution—Angle Class II malocclusion with no crowding in the mandibular arch OR Angle Class I malocclusion with sufficient crowding to necessitate mandibular extractions. | Profile: generally, a balanced, relatively straight profile is ideal. Shape and color of canine; once too much does not have to be removed the shape can be modified, the color can be adjusted by bleaching and if not adequate, veneers. Smiling lip level; Positioning the natural canine’s gingival margin slightly incisal to the central incisor gingival margin is recommended. | Patient selection depends on the type of malocclusion, profile, the shape and color of the canines, and smiling level of the lips. These selection criteria must be evaluated prior to treatment in order to guarantee both treatment success and consistent esthetics. |

| Managing Congenitally Missing Lateral Incisors Part 2: Tooth-Supported Restorations | 2005 | Kokich Jr and Kinzer [44] | Review article | N/A | Discussion of the most important parameters to consider for Fixed Partial Denture and a comparison between Resin Bonded, Full Coverage or Cantilevered fixed partial denture | The most conservative tooth-supported restoration is the resin-bonded fixed partial denture, followed by the Cantilever fixed partial denture. The least conservative of all is a conventional full-coverage fixed partial denture. | Many restorative options exist. Depending on the type of final restoration that is chosen, interdisciplinary management of patients with congenitally missing lateral incisors often plays a vital role in the facilitation of treatment. |

| TALON CUSP AND GEMINATED TEETH | |||||||

| Title | Year | Authors | Study Design | Population | Intervention | Comparison | Outcome |

| Bilateral geminated teeth with talon cusps: A case report | 2012 | Sener, S. and Unlu, N. and Basciftci, F.A. and Bozdag, G. [65] | Case report | Adolescent 17 yr boy | Talon cusps in both incisors were gradually reduced on two consecutive sittings held 6–8 weeks apart. The distinct enamel grooves running buccolingually on both central incisors were restored with a composite resin, and the esthetic appearance of anterior teeth was improved. | The purpose of the waiting period for cuspal reduction is to allow for the deposition of reparative dentin for pulpal protection and to avoid pulpal exposure. After both grinding procedures, the exposed surface was treated with fluoride gel as a desensitizing agent. | Patient was satisfied with the outcome. |

| Management of a facial talon cusp on a maxillary permanent central incisor: a case report and review of the literature | 2014 | Yazıcıoğlu, O. and Ulukapı, H. [62] | Case Report and Review of Literature | 21 yr old Female | Minimal restorative treatment. The talon cusp was gradually reduced with a high-speed hand piece. The cusp was nearly completely eliminated without causing pulpal exposure. Direct resin-based composite was used. | Generally, the talon cusp area is grinded until reaching healthy tooth tissue. For this purpose, the labial surface of the tooth is painted with articulating paper. The purpose of this process is to ensure careful grinding. | Satisfied patient. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

McGarty, N.R.; Delre, C.; Gaeta, C.; Doldo, T. Corrections of Dental Anomalies in the Maxillary Incisors and Their Influence on Perceived Smile Esthetics: A Systematic Review. Bioengineering 2025, 12, 262. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering12030262

McGarty NR, Delre C, Gaeta C, Doldo T. Corrections of Dental Anomalies in the Maxillary Incisors and Their Influence on Perceived Smile Esthetics: A Systematic Review. Bioengineering. 2025; 12(3):262. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering12030262

Chicago/Turabian StyleMcGarty, Nessa Rose, Caterina Delre, Carlo Gaeta, and Tiziana Doldo. 2025. "Corrections of Dental Anomalies in the Maxillary Incisors and Their Influence on Perceived Smile Esthetics: A Systematic Review" Bioengineering 12, no. 3: 262. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering12030262

APA StyleMcGarty, N. R., Delre, C., Gaeta, C., & Doldo, T. (2025). Corrections of Dental Anomalies in the Maxillary Incisors and Their Influence on Perceived Smile Esthetics: A Systematic Review. Bioengineering, 12(3), 262. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering12030262