Waste Activated Sludge-High Rate (WASHR) Treatment Process: A Novel, Economically Viable, and Environmentally Sustainable Method to Co-Treat High-Strength Wastewaters at Municipal Wastewater Treatment Plants

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Analytical Methods

2.2. Winery Wastewater and Anaerobic Digester Supernatant

2.3. Mixed Liquor

2.4. Experimental Set-Up and Procedures

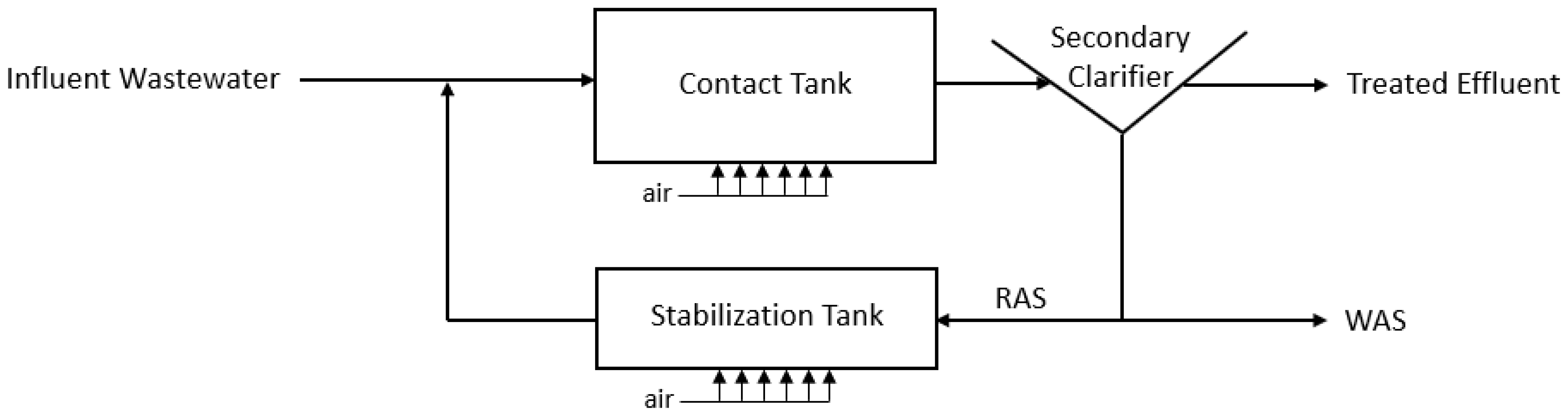

3. Configuration and Performance of the WASHR Process

3.1. WASHR System Configuration, Theory, and Concept

- Step 1: fill cycle: WAS and high-strength wastewater are added to the contact tank; if necessary, the municipal WWTP’s effluent can be added to dilute the WAS.

- Step 2: react cycle: the contact tank is continuously aerated, during which time organic and other contaminants are sorbed onto the biological floc.

- Step 3: settle cycle: aeration ceases, and the contact tank contents are allowed to settle under quiescent conditions.

- Step 4: empty cycle: the clarified supernatant is directed to the liquid treatment train of the municipal WWTP, and the settled biomass is transferred to the WASHR stabilization tank; at the end of this four-step process, the WASHR contact tank is empty and ready for another batch treatment cycle.

- Step 5: idle cycle: the empty contact tank awaits the start of the next fill cycle.

- Step 1: fill cycle: during the empty cycle of the contact stage, settled biomass is directed to the stabilization tank, which marks the start of the stabilization stage’s fill cycle.

- Step 2: aeration cycle: the settled biomass is continuously aerated, allowing the biomass to continue oxidizing the organic material sorbed during the contact phase.

- Step 3: empty cycle: the settled, stabilized biomass is emptied out of the stabilization tank and directed to the municipal WWTP’s digestion process for further treatment.

- Step 4: idle cycle: the empty stabilization tank enters the idle cycle, awaiting the transfer of the settled biomass from the empty cycle of the next contact stage.

3.2. Bench-Scale Trials

3.2.1. Contact Stage Performance

3.2.2. Stabilization Stage Performance

3.3. Discussion and Analysis

4. Economic and Environmental Impact Analysis

4.1. Capital and Operating Costs

4.2. Quantifying Greenhouse Gas Emissions

4.3. Case Study

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- MOE. Ministry of the Environment Design Guidelines for Sewage Works. 2008. Available online: https://www.ontario.ca/document/design-guidelines-sewage-works-0 (accessed on 1 October 2018).

- Metcalf & Eddy; Tchobanoglou, G.; Stensel, D.; Tsuchihashi, R.; Burton, F.L. Wastewater Engineering: Treatment and Resource Recovery, 5th ed.; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2014; ISBN 978-0-07-340118-8. [Google Scholar]

- Carr, S.; Kobylinski, E.; Long, J.; Swezy, R.; Nolkemper, D. What to consider before you co-digest FOG. Water Environ. Technol. 2018, 2018, 24–29. [Google Scholar]

- Mehariya, S.; Patel, A.K.; Obulisamy, P.K.; Punniyakotti, E.; Wong, J.W. Co-digestion of food waste and sewage sludge for methane production: Current status and perspective. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 265, 519–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, M.B.; Mehrvar, M. Winery wastewater management and treatment in Niagara Region, Ontario, Canada: A review and analysis of current regional practices and treatment performance. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 2020, 98, 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, X.; Xu, Y.; Dai, X. Biohythane production from two-stage anaerobic digestion of food waste: A review. J. Environ. Sci. 2023, 139, 334–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchis-Perucho, P.; Torres KM, M.; Ferrer, J.; Robles, Á. Evaluating the potential of off-line methodologies to determine sludge filterability from different municipal wastewater treatment systems. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 648, 143537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szaja, A.; Montusiewicz, A.; Lebiocka, M. Variability of micro- and macro-elements in anaerobic co-digestion of municipal sewage sludge and food industrial by-products. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrijos, M.; Moletta, R. Winery wastewater depollution by sequencing batch reactor. Water Sci. Technol. 1997, 35, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eusebio, A.; Petruccioli, M.; Lageiro, M.; Federici, F.; Duarte, J. Microbial characterisation of activated sludge in jet-loop bioreactors treating winery wastewaters. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2004, 31, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolzonella, D.; Zanette, M.; Battistoni, P.; Cecchi, F. Treatment of winery wastewater in a conventional municipal activated sludge process: Five years of experience. Water Sci. Technol. 2007, 56, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bolzonella, D.; Papa, M.; Da Ros, C.; Muthukumar, L.A.; Rosso, D. Winery wastewater treatment: A critical overview of advanced biological processes. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2019, 39, 489–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, M.B.; Mehrvar, M. An assessment of the grey water footprint of winery wastewater in the Niagara Region of Ontario, Canada. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 214, 623–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.B.; Mehrvar, M. From field to bottle: Water footprint estimation in the winery industry. In Water Footprint Assessment and Case Studies; Muthu, S.S., Ed.; Environmental Footprints and Eco-Design of Products and Processes; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2021; pp. 103–136. [Google Scholar]

- Wines of Canada. List of Ontario, Canada Wineries. 2021. Available online: http://www.winesofcanada.com/list_ont.html (accessed on 22 April 2021).

- Wines of Canada. Ontario. 2017. Available online: www.winesofcanada.com/Ontario.html (accessed on 29 May 2017).

- Johnson, M.B.; Mehrvar, M. Characterising winery wastewater composition to optimize treatment and reuse. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2020, 26, 410–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrvar, M.; Johnson, M.B. Method and System for Pre-Treating High Strength Wastewater. International Patent Application No. PCT/CA2022/050507 (WO 2022/204823), 4 April 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Bridgewater, L.; American Public Health Association; American Water Works Association; Water Environment Federation. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater, 22nd ed.; APHA (American Public Health Association): Washington, DC, USA, 2012; ISBN 0875530133. [Google Scholar]

- Gancarczyk, J. Activated Sludge Process: Theory and Practice; Marcel Dekker: New York, NY, USA, 1983; ISBN 0-8247-1758-9. [Google Scholar]

- Bustamante, M.A.; Paredes, C.; Moral, R.; Moreno-Caselles, J.; Perez-Espinosa, A.; Perez-Murcia, M.D. Uses of winery and distillery effluents in agriculture: Characterisation of nutrient and hazardous components. Water Sci. Technol. 2005, 51, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lofrano, G.; Meric, S. A comprehensive approach to winery wastewater treatment: A review of the state-of-the-art. Desalination Water Treat. 2016, 57, 3011–3028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.B.; Mehrvar, M. Co-treatment of winery and domestic wastewaters in municipal wastewater treatment plants: Analysis of biodegradation kinetics and process performance impacts. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wines and Vines. B.C. Winery Ferments Water—Tantalus Vineyards Purifies Wastewater in Sequencing Batch Reactor. 2021. Available online: https://winesvinesanalytics.com/news/article/87687/BC-Winery-Ferments-Water (accessed on 22 April 2021).

- International Sugar Organization. Daily Sugar Prices. 2021. Available online: https://www.isosugar.org/prices.php (accessed on 22 April 2021).

- Environment and Climate Change Canada. National Inventory Report 1990–2018: Greenhouse Gas Sources and Sinks in Canada—Part 3, Table A13-7. 2020. Available online: http://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2020/eccc/En81-4-2018-3-eng.pdf (accessed on 22 April 2021).

- Caivano, M.; Bellandi, G.; Mancini, I.M.; Masi, S.; Brienza, R.; Panariello, S.; Gori, R.; Caniani, D. Monitoring the aeration efficiency and carbon footprint of a medium-sized WWTP: Experimental results on oxidation tank and aerobic digester. Environ. Technol. 2017, 38, 629–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czepiel, P.; Crill, P.M.; Harris, R.C. Nitrous oxide emission frommunicipal wastewater treatment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1995, 29, 2352–2356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mannina, G.; Ekama, G.; Caniani, D.; Cosenza, A.; Esposito, G.; Gori, R.; Garrido-Baserba, M.; Rosso, D.; Olsson, G. Greenhouse gases from wastewater treatment–a review of modelling tools. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 551–552, 254–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gogolek, P. Methane Emission Factors for Biogas Flares; International Flame Research Foundation: Sheffield, UK, 2012; ISSN 2075-3071. Available online: https://ifrf.net/research/archive/methane-emission-factors-for-biogas-flares/# (accessed on 28 April 2020).

- Bai, R.L.; Jin, L.; Sun, S.R.; Cheng, Y.; Wei, Y. Quantification of greenhouse gas emission from wastewater treatment plants. Greenh. Gases Sci. Technol. 2022, 12, 587–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | WWW | Digester Supernatant |

|---|---|---|

| COD (mg/L) | 163,000 | 1200 |

| TOC (mg/L) | 57,300 | 259 |

| TSS (mg/L) | 71,600 | 556 |

| VSS (mg/L) | 51,600 | 438 |

| TAN (mg/L) | 10.9 | 246 |

| TP (mg/L) | 30.2 | 32.5 |

| Parameter | Unit | Run A | Run B | Run C | Run D |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contact Stage | |||||

| MLSSo | mg/L | 1488 | 1488 | 1488 | 1488 |

| MLVSSo | mg/L | 1244 | 1244 | 1244 | 1244 |

| Operating Volume | L | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 |

| Reaction Cycle Duration | h | 3 and 6 | 3 and 6 | 3 and 6 | 3 and 6 |

| Settle Cycle Duration | h | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Stabilization Stage | |||||

| Operating Volume | L | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| Aeration Cycle Duration | h | 18 | 18 | 18 | 18 |

| Feed Volumes | |||||

| WWW | L | 0.14 | 0.28 | 0.42 | 0.56 |

| Digester Supernatant | L | 0.54 | 0.54 | 0.54 | 0.54 |

| Initial Concentrations (1) | |||||

| CODo | mg/L | 1751 | 3381 | 5010 | 6639 |

| TOCo | mg/L | 583 | 1156 | 1729 | 2302 |

| TSSo | mg/L | 757 | 1473 | 2188 | 2904 |

| VSSo | mg/L | 551 | 1066 | 1582 | 2098 |

| TANo | mg/L | 32.1 | 31.9 | 31.8 | 31.7 |

| TKNo | mg/L | 47.7 | 49.1 | 50.6 | 52.1 |

| TPo | mg/L | 2.07 | 2.37 | 2.66 | 2.96 |

| Total Effluent Volumes (2) | |||||

| Clarified Supernatant | L | 7.1 | 7.1 | 7.1 | 7.1 |

| Settled Biomass | L | 6.9 | 6.9 | 6.9 | 6.9 |

| Parameter | Unit | Run A | Run B | Run C | Run D |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TS | |||||

| Pre-Stabilization | mg/L | 4859 | 6177 | 7251 | 8230 |

| Post-Stabilization | mg/L | 4500 | 5480 | 6000 | 6860 |

| Removal Rate | % | 7.4 | 11.3 | 17.3 | 16.6 |

| VS | |||||

| Pre-Stabilization | mg/L | 3221 | 4143 | 4991 | 5594 |

| Post-Stabilization | mg/L | 3250 | 4020 | 4410 | 5080 |

| Removal Rate | % | −0.9 | 3.0 | 11.6 | 9.2 |

| TSS | |||||

| Pre-Stabilization | mg/L | 4060 | 4685 | 5443 | 5826 |

| Post-Stabilization | mg/L | 4440 | 5297 | 5995 | 6390 |

| Removal Rate | % | −9.3 | −13.1 | −10.1 | −9.7 |

| COD | |||||

| Pre-Stabilization | mg/L | 5688 | 7439 | 9831 | 11,300 |

| Post-Stabilization | mg/L | 6920 | 7380 | 7980 | 9400 |

| Removal Rate | % | −21.7 | 0.8 | 18.8 | 16.8 |

| Parameter | Reduction in Loadings to | |

|---|---|---|

| Liquid Treatment Train | Solids Treatment Train | |

| COD | 81.4% | 59.6% |

| TOC | 83.6% | - |

| TSS | 92.8% | 30.2% |

| VS | - | 47.9% |

| TAN | 59.3% | - |

| Parameter | Unit | Liquid Treatment Train Co-Treatment | Solids Treatment Train Co-Treatment | WASHR Pre-Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short-Term | ||||

| Capital Cost | CAD | 2,470,000 | 2,510,000 | 2,590,000 |

| O&M Cost | CAD/yr | 115,100 | 53,000 | 67,900 |

| LCC Cost (15 Years) | CAD | 3,898,800 | 3,122,800 | 3,447,500 |

| Cost per Unit of Treated WWW | CAD/m3 | 54.15 | 43.37 | 47.88 |

| GHG Emissions | eCO2 ton/yr | 771 | 2204 | 959 |

| Long-Term | ||||

| Capital Cost | CAD | 8,520,000 | 5,580,000 | 6,770,000 |

| O&M Cost | CAD/yr | 118,200 | 55,400 | 69,500 |

| LCC Cost (25 Years) | CAD | 10,685,000 | 6,489,100 | 8,077,300 |

| Cost per Unit of Treated WWW | CAD/m3 | 89.04 | 54.08 | 67.31 |

| GHG Emissions | eCO2 ton/yr | 771 | 2205 | 960 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Johnson, M.B.; Mehrvar, M. Waste Activated Sludge-High Rate (WASHR) Treatment Process: A Novel, Economically Viable, and Environmentally Sustainable Method to Co-Treat High-Strength Wastewaters at Municipal Wastewater Treatment Plants. Bioengineering 2023, 10, 1017. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering10091017

Johnson MB, Mehrvar M. Waste Activated Sludge-High Rate (WASHR) Treatment Process: A Novel, Economically Viable, and Environmentally Sustainable Method to Co-Treat High-Strength Wastewaters at Municipal Wastewater Treatment Plants. Bioengineering. 2023; 10(9):1017. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering10091017

Chicago/Turabian StyleJohnson, Melody Blythe, and Mehrab Mehrvar. 2023. "Waste Activated Sludge-High Rate (WASHR) Treatment Process: A Novel, Economically Viable, and Environmentally Sustainable Method to Co-Treat High-Strength Wastewaters at Municipal Wastewater Treatment Plants" Bioengineering 10, no. 9: 1017. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering10091017

APA StyleJohnson, M. B., & Mehrvar, M. (2023). Waste Activated Sludge-High Rate (WASHR) Treatment Process: A Novel, Economically Viable, and Environmentally Sustainable Method to Co-Treat High-Strength Wastewaters at Municipal Wastewater Treatment Plants. Bioengineering, 10(9), 1017. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering10091017