1. Introduction

Climate change is altering the hydrologic cycle in ways that challenge reservoir systems designed around historical seasonality and stationarity. Warmer temperatures increase atmospheric demand and evaporative losses, intensifying heavy precipitation and increasing both drought and flood risks within the same watershed [

1,

2,

3]. For water supply reservoirs, the key operational question is not only whether annual inflow changes, but whether seasonal refill timing shifts and whether stressful warm-season conditions become more frequent [

4,

5,

6].

Recent extremes illustrate why these changes matter for water resources operations. Event attribution studies show that anthropogenic warming can increase the intensity of extreme rainfall, thereby worsening flood hazards and stressing flood management infrastructure (e.g., the 2021 Western European floods) [

7,

8]. Similar attribution evidence exists for the 2022 Pakistan floods [

9]. In the United States, the growing frequency and cost of weather and climate disasters highlight the increasing exposure of water systems to compound hazards [

10]. In Texas, Hurricane Harvey (2017) produced multi-day rainfall totals exceeding 1500 mm in some locations and caused approximately

$125 billion in damages [

11,

12].

At the other end of the hydrologic spectrum, persistent warm-season water deficits are becoming more consequential for water supply reliability. Multi-year drought crises, such as the 2020–2023 Horn of Africa drought [

13] and the 2000–2023 western U.S. megadrought, illustrate how deficits can persist beyond the buffering capacity of storage when inflows remain suppressed for several consecutive years. The west U.S. megadrought is the driest 23-year period in at least 1200 years, and anthropogenic warming has contributed substantially to soil moisture deficits that intensify hydrologic drought impacts [

6,

14]. For reservoir operations, these conditions are especially challenging when high heat and low rainfall coincide, because such compound periods align with peak water demand, low inflows, and reduced operating margins for storage and releases [

4].

Texas is particularly exposed to climate-driven water supply stress because rapid population growth and climate variability converge on a finite reservoir system. The Texas Water Development Board projects that the statewide population will grow from 29 million in 2020 to more than 51 million by 2070, with water demand increasing by about 22% [

15]. The Dallas–Fort Worth metropolitan area exceeds 8 million residents and continues to grow rapidly [

16], increasing reliance on surface water reservoirs and heightening sensitivity to seasonal inflow variability and multi-year drought.

Observed records already show warming in Texas and increasing precipitation variability, with more intense rainfall events interspersed with longer dry spells [

10,

17]. Regional assessments project additional warming and increased intensity of extreme precipitation in the remainder of the 21st century [

18,

19,

20]. Together, these trends imply a more challenging operating envelope for reservoirs: greater warm-season demand and evaporation losses, more frequent hot–dry conditions, and episodic floods that must be buffered without compromising supply reliability.

Together, these lines of evidence emphasize that mean changes alone do not capture the operational stressors that matter most: persistence of deficits, seasonality shifts, and extremes at both tails of the distribution. Accordingly, in addition to SWAT-based inflow projections, we include time series diagnostics and threshold-based indicators to connect projected changes to the historical structure of variability and to decision-relevant triggers.

Eagle Mountain Lake, a reservoir in the Upper West Fork Trinity River basin managed by the Tarrant Regional Water District, supplies drinking water to nearly half a million North Texas residents [

21]. Despite its strategic role, peer-reviewed evidence linking projected watershed-scale inflow changes to operationally relevant signals in the reservoir record (storage, releases, and flood discharge) remains limited for this system. This gap matters because management decisions are driven by thresholds (e.g., seasonal refill levels and flood release triggers), not only by annual mean changes.

Watershed models, such as the Soil and Water Assessment Tool (SWAT), provide a practical framework for translating climate scenarios into daily streamflow responses and seasonal shifts in inflow [

22,

23]. However, many climate impact studies stop at changes in hydrologic statistics, while operators need interpretable indicators that map directly to decisions, such as refill-season inflow reliability, drought trigger frequency, and the occurrence of hot–dry months that coincide with high demand. By combining SWAT projections with observed reservoir operations, this study offers a transparent, management-focused interpretation of climate risks without requiring simulation of proprietary operating rules.

This study aims to quantify how projected climate change may alter streamflow entering Eagle Mountain Lake and to translate those changes into operationally relevant risk signals using the historical reservoir record. Specific objectives are to: (i) develop and evaluate a SWAT model for the Upper West Fork Trinity watershed using long-term USGS streamflow observations; (ii) generate station-scale downscaled daily climate inputs from CMIP6 projections under SSP1-2.6, SSP2-4.5, and SSP5-8.5 for a baseline period (2003–2022) and two future windows (2031–2050; 2081–2100); (iii) quantify projected changes in annual, seasonal, and monthly inflow to the reservoir and characterize inter-model uncertainty; (iv) evaluate historical reservoir storage dynamics and threshold-based performance metrics to characterize drought exposure; and (v) link climate stress metrics, including extreme heat days and “hot–dry months”, to observed operations (water supply releases, lake level, and flood discharge) to provide a compound event framing that matches management reality.

The distinctive contribution of this work is an operational reframing of a standard SWAT-plus-climate workflow. Projected hydroclimatic changes are translated into decision-relevant indicators using the historical operations record: (i) refill-season inflow shifts (March–June), (ii) a hot–dry month metric aligned with warm-season demand, and (iii) storage threshold performance and screening-level probabilities linked to multi-year inflow deficits. This framing is intended to bridge watershed projections and threshold-based reservoir management without requiring simulation of proprietary operating rules.

2. Materials and Methods

For readability, this section is organized into study materials (study area and datasets) and methods (SWAT setup, calibration/validation, CMIP6 downscaling, and statistical/operations analyses). A schematic overview of the end-to-end workflow is provided in

Figure 1.

2.1. Study Area

The study focuses on the Eagle Mountain Lake Reservoir watershed in the Upper West Fork Trinity River basin (Hydrologic Unit Code 12030101) in North-Central Texas, USA (

Figure 2). Eagle Mountain Lake is located in Tarrant and Wise counties, approximately 8 km (5 mi) northwest of Fort Worth (centered near 32.92° N, 97.50° W) within the Dallas–Fort Worth metropolitan region. The modeled watershed outlet corresponds to the USGS West Fork Trinity River near Boyd gauge (08044500), which drains approximately 4468 km

2 upstream of the reservoir. Eagle Mountain Lake has a conservation (normal) storage capacity of approximately 228 million m

3 at a conservation pool elevation of about 197.8 m above mean sea level, making it a strategically important component of regional water supply planning.

Land cover in the watershed is dominated by pasture and agricultural lands (65%), followed by forests (18%), urban areas (9%), and other land uses, including water bodies, wetlands, shrublands, and barren land (8%) [

24]. The watershed experiences a humid subtropical climate (Köppen–Geiger classification Cfa) characterized by hot summers and mild winters [

25]. Based on the seven station records used in this study, mean annual temperature during the baseline period (2003–2022) ranges from 17.8 to 19.0 °C, and mean annual precipitation ranges from 750 to 891 mm. The U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) maintains four active streamflow gauging stations within the watershed, providing discharge measurements for model calibration and validation (

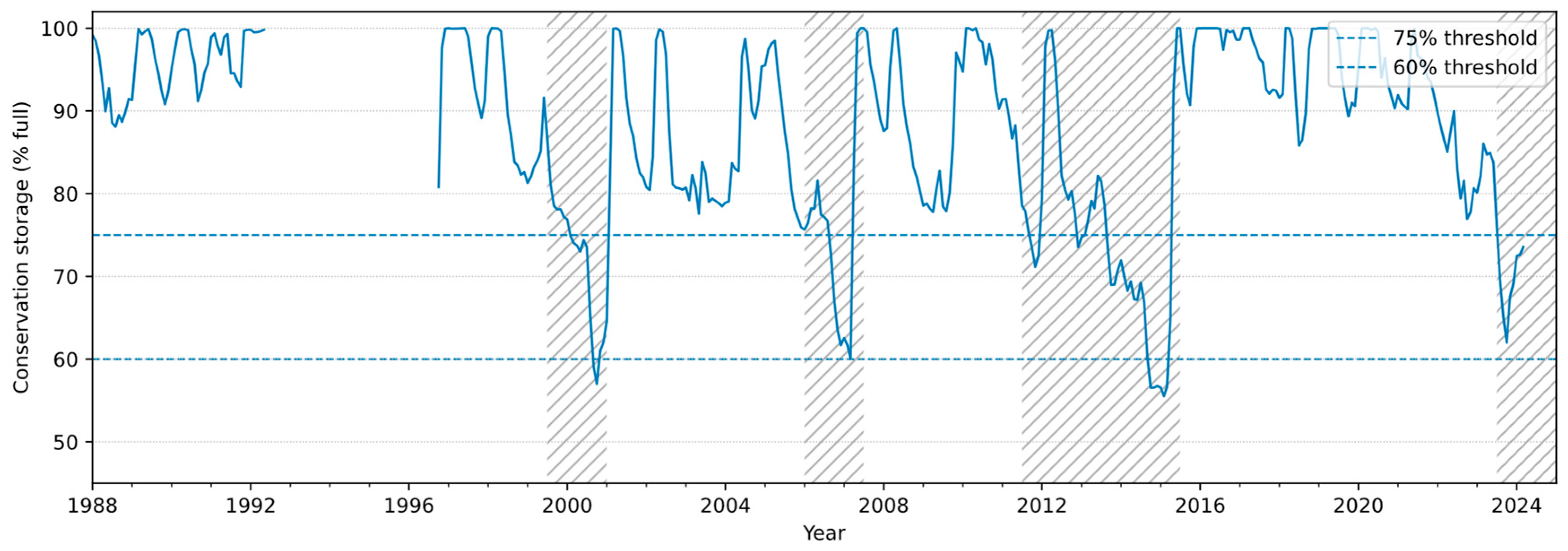

Table 1). Eagle Mountain Lake was impounded in 1932. Daily reservoir observations for 1988–2024 indicate that lake surface elevation fluctuated between 194.5 and 200.2 m, and conservation storage ranged from near full pool to approximately 54% during the drought of record [

21,

26]. In addition to municipal water supply, the reservoir supports recreational activities including fishing, boating, and water sports, generating approximately

$1.7 million in annual revenue [

21].

2.2. Hydrological Model Description

The Soil and Water Assessment Tool (SWAT) is a physically based, semi-distributed hydrological model developed by the U.S. Department of Agriculture-Agricultural Research Service (USDA-ARS) to simulate the impacts of land management practices on water, sediment, and agricultural chemical yields in large, complex watersheds [

22,

27]. The SWAT operates on a daily step and divides watersheds into subbasins based on topography, which are further subdivided into Hydrologic Response Units (HRUs), unique combinations of land use, soil type, and slope class that represent homogeneous areas with similar hydrological behavior. The SWAT model simulates the complete terrestrial water cycle, including precipitation, canopy interception, infiltration, evapotranspiration, surface runoff, lateral subsurface flow, groundwater recharge, and channel routing, with the water balance equation governing each HRU.

2.3. Input Data and Model Setup

Model development utilized ArcSWAT version 2012.10.8.26, an ArcGIS 10.8.0 interface compatible with SWAT executable version 687 (swat.tamu.edu). Four primary data layers were required for model construction: (1) topography, (2) land use/land cover, (3) soils, and (4) climate data (

Table A1).

A 10 m resolution Digital Elevation Model (DEM) was obtained from the USGS National Elevation Dataset and processed to derive watershed boundaries, stream networks, flow direction, and slope characteristics. Land use/land cover data were obtained from the USDA National Agricultural Statistics Service Cropland Data Layer (2016), which provides 30 m resolution classification based on a modified Anderson Level II system [

24]. The original 16 land classes were reclassified into eight broader categories: agricultural land, barren land, forests, urban areas, grass/pasture, wetlands, open water bodies, and shrubland. Soil data were obtained from the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) gridded Soil Survey Geographic (gSSURGO) database, providing detailed information on soil physical and hydrological properties. Soils were classified into four hydrologic soil groups (A–D) based on infiltration capacity, with Group A representing high-infiltration sandy soils and Group D representing low-infiltration clay soils with high runoff potential (

Table A2). Climate data, including daily precipitation and minimum/maximum temperature, were compiled for seven stations/grid points (five stations and two PRISM gridded points) for the period 2003–2022 (

Table A3). Station and grid point metadata are retained in the SWAT project input files. Watershed delineation using the 10 m DEM resulted in 25 subbasins. Subsequent HRU delineation, based on unique combinations of land use, soil type, and slope class (<2%, 2–5%, >5%), generated 2118 HRUs. The model was run for the period 1990–2022, with a three-year warm-up period (1990–1992) to allow model state variables to reach equilibrium.

2.4. Model Calibration and Validation

Model calibration and validation were performed using SWAT-CUP Premium [

28], employing the SWAT Parameter Estimator (SPE) algorithm with stochastic calibration. Twenty-two parameters controlling surface runoff, baseflow, groundwater, evapotranspiration, and channel routing processes were selected for calibration based on a literature review and preliminary sensitivity analysis (

Table A4). A global sensitivity analysis using a multiple regression approach with Latin Hypercube sampling identified the most influential parameters, with significance assessed using t-statistics and

p-values. Daily discharge observations from these gauges extend through the calibration/validation period (1990–2022);

Table 1 lists the period of record start dates for reference.

Calibration was performed separately for four USGS gauge stations (

Table 1) representing different drainage areas and streamflow regimes within the watershed. Watershed, draining to USGS station 08044500 (West Fork Trinity River near Boyd, TX, USA), represents the primary inlet to Eagle Mountain Lake and encompasses 4462 km

2 (approximately 80% of the total watershed area). For each USGS gauge, 2000 model iterations were executed across four calibration rounds, with parameter ranges progressively refined based on simulation results.

Model performance was assessed using a suite of five complementary statistical metrics to provide a comprehensive evaluation of the agreement between simulated and observed streamflow: the coefficient of determination (R

2), Nash–Sutcliffe Efficiency (NSE), Kling–Gupta Efficiency (KGE), Percent Bias (PBIAS), and the RMSE observations standard deviation ratio (RSR). This multi-metric approach was adopted to capture different aspects of model performance, including correlation, bias, variability, and overall predictive accuracy. NSE was computed as

NSE = 1 − [Σ(

Qobs −

Qsim)

2/Σ(

Qobs −

Qmean)

2], where

Qobs and

Qsim are observed and simulated discharge, and

Qmean is the observed mean. KGE was computed as

KGE = 1 − [(

r − 1)

2 + (

α − 1)

2 + (

β − 1)

2]

1/2, where

r is the correlation coefficient,

α is the variability ratio (

σsim/

σobs), and

β is the bias ratio (

μsim/

μobs). PBIAS was computed as

PBIAS = 100 × Σ(

Qsim −

Qobs)/Σ(

Qobs), and RSR was computed as

RMSE/

σobs. For detailed methodological frameworks on SWAT model calibration and uncertainty analysis, readers are referred to Abbaspour et al. [

28].

2.5. Future Climate Scenarios

Future climate projections were generated using the Long Ashton Research Station Weather Generator (LARS-WG) version 8.0 [

29,

30], a stochastic weather generator that produces site-specific daily weather data under both baseline and climate change scenarios. LARS-WG was calibrated using 33 years (1990–2022) of observed daily precipitation and temperature data from each of the seven weather stations in the study area. Model performance was evaluated using chi-square goodness-of-fit tests,

t-tests, and F-tests comparing the statistical properties of observed and simulated weather series.

Climate change scenarios were derived from five Global Climate Models (GCMs) participating in the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6): ACCESS-ESM1-5 (Australia), CNRM-CM6-1 (France), HadGEM3-GC31-LL (UK), MPI-ESM1-2-LR (Germany), and MRI-ESM2-0 (Japan) (

Table A5). These models were selected because they are implemented within LARS-WG (enabling consistent site-scale statistical downscaling at all seven locations), originate from different modeling centers (providing structural diversity), and span a range of warming rates and hydroclimate responses over North America. We treat the resulting five-model ensemble as a scenario set to bracket uncertainty rather than a probabilistic forecast; therefore, results are reported as ensemble summaries (means and uncertainty ranges) consistent with known inter-model spread in CMIP6 precipitation projections and model sensitivity differences [

31,

32]. Projections were obtained for three Shared Socioeconomic Pathways: SSP1-2.6 (sustainable development, low emissions), SSP2-4.5 (middle-of-the-road development, moderate emissions), and SSP5-8.5 (fossil-fueled development, high emissions), representing radiative forcing of 2.6, 4.5, and 8.5 W/m

2 by 2100, respectively [

33,

34]. Downscaled daily series were generated for each of the seven station/grid point locations used in this study (

Table A3).

Daily climate time series used to force the SWAT and to compute climate metrics were assembled for seven stations within the study area (Alvord, Boyd, Bridgeport, Markley, Newport, PRISM1, PRISM2). The historical baseline spans 2003–2022 and includes daily precipitation and minimum/maximum temperature. Future daily series were developed for two windows, 2031–2050 (2030s) and 2081–2100 (2080s), for five CMIP6 GCMs (

Table A5) under SSP1-2.6, SSP2-4.5, and SSP5-8.5. These daily series were used both to drive SWAT simulations and to quantify changes in mean climate, extremes, and management-relevant compound conditions.

Management-relevant climate stress metrics were computed from the downscaled daily series and applied consistently across historical and future periods. Extreme heat days were defined as days with Tmax exceeding the station-specific 95th percentile of the baseline (2003–2022). Hot–dry months were defined as months with a monthly mean Tmax exceeding the station-specific 90th percentile of the baseline and monthly precipitation below the baseline median. Percentile-based temperature thresholds normalize for spatial differences among stations/grid points and identify unusually hot months that remain frequent enough to be operationally meaningful, while the median precipitation threshold provides a robust separator of below-normal rainfall months given precipitation skewness. The combined hot–dry criterion captures periods when atmospheric demand (and typically warm-season water demand) is high while rainfall–runoff generation is suppressed, aligning with conditions that historically coincide with storage drawdown and higher water supply releases.

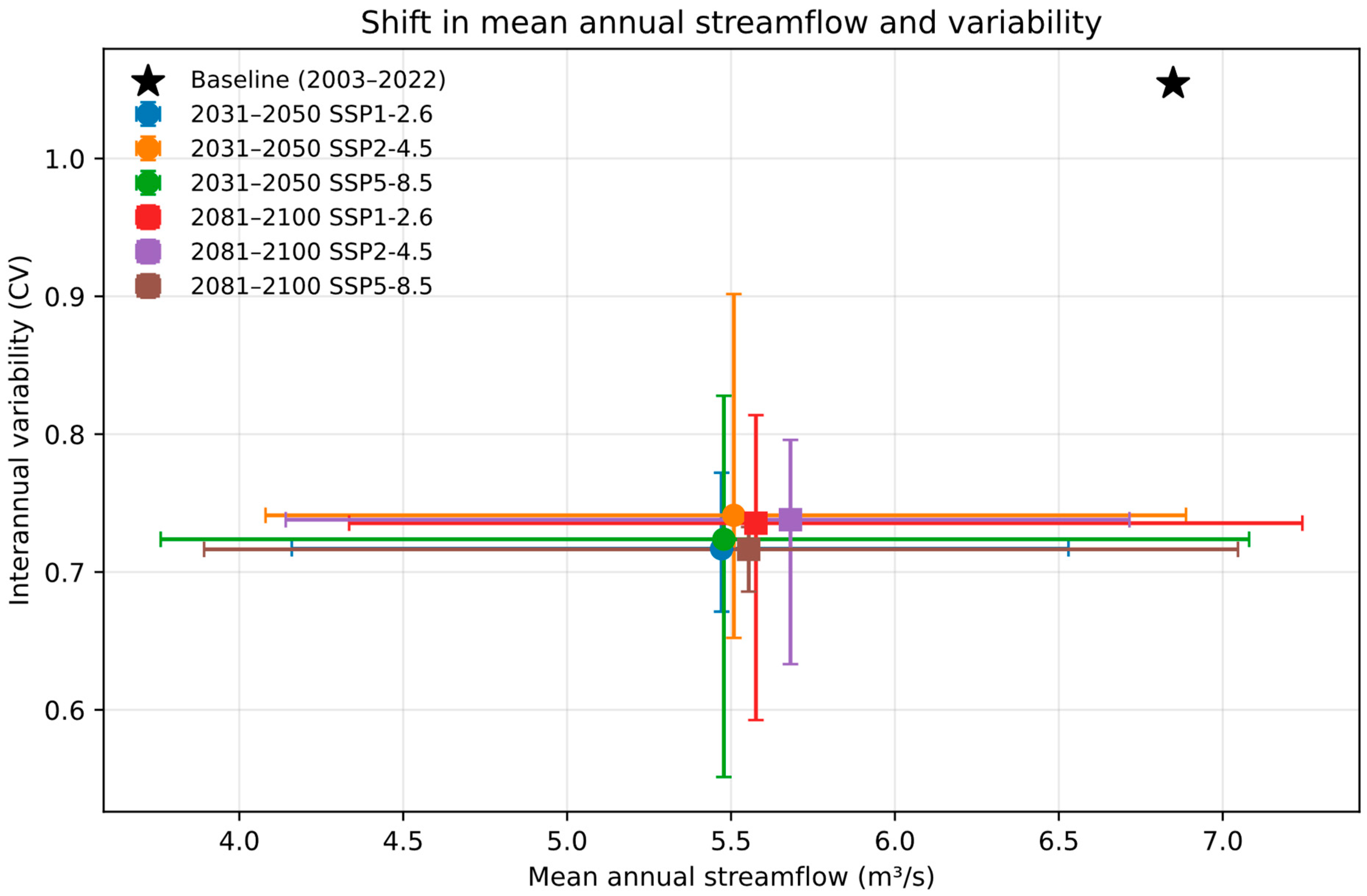

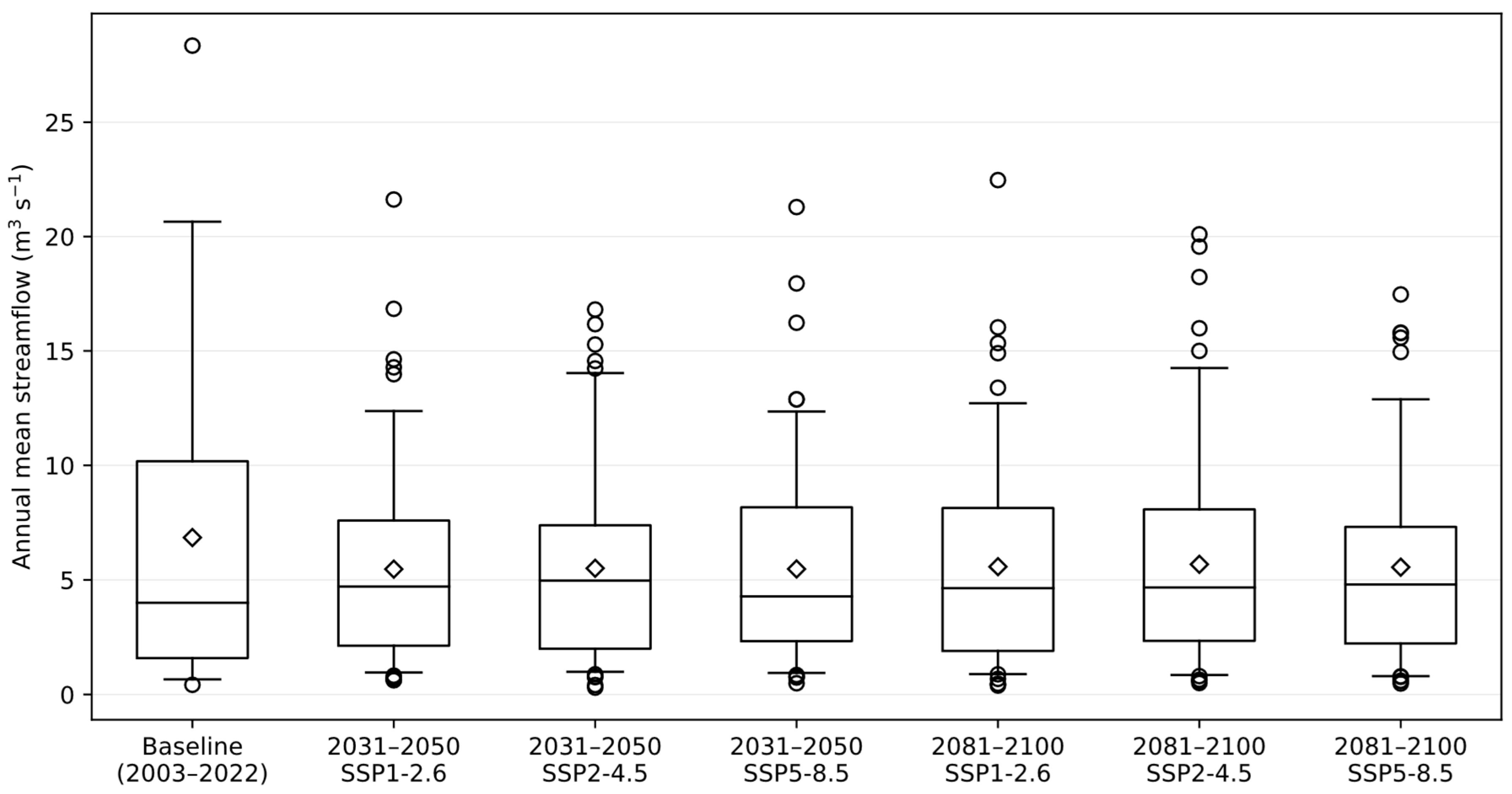

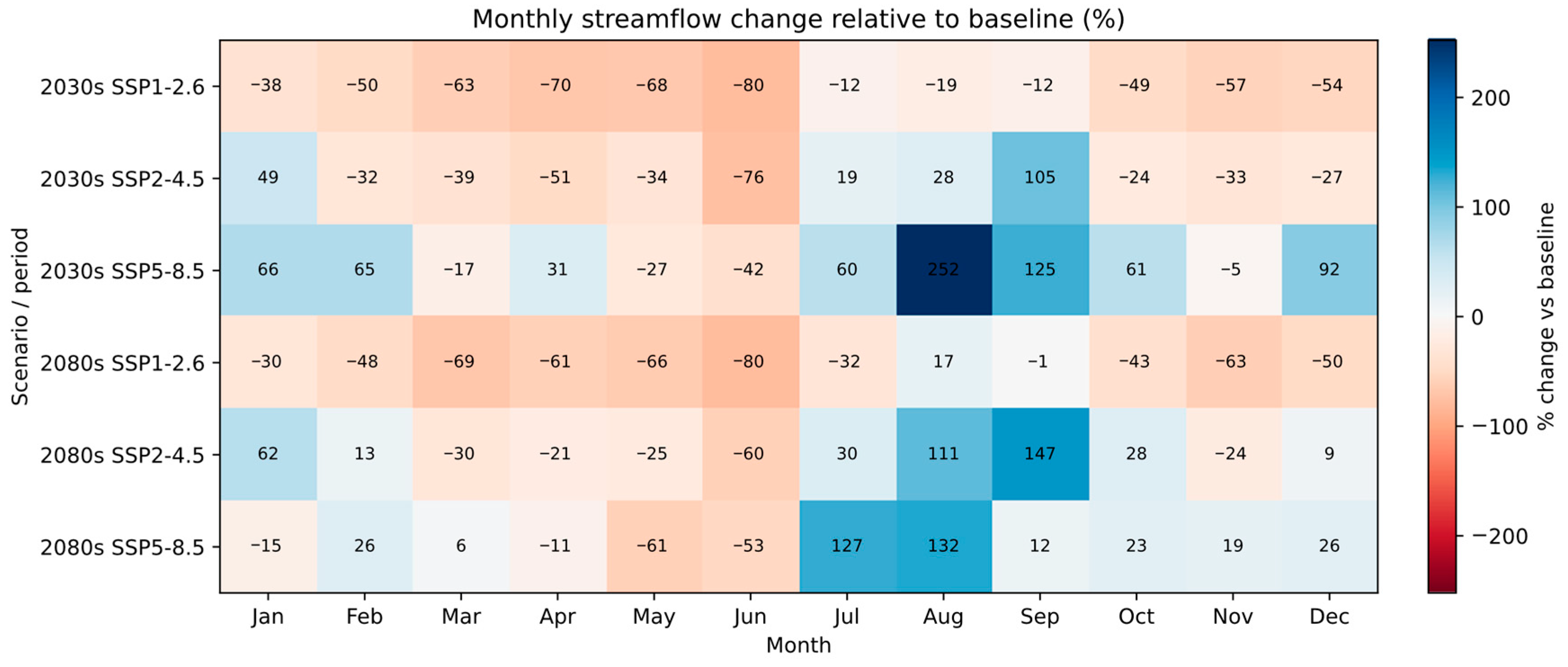

2.6. Statistical Analysis and Uncertainty Characterization

Streamflow change was quantified at annual, seasonal, and monthly scales using ensemble summaries across five GCMs. Annual and monthly distributions are reported using the mean, median, coefficient of variation (CV), and the 5th–95th percentile range (Q5–Q95). Percent changes were computed relative to the baseline mean (2003–2022).

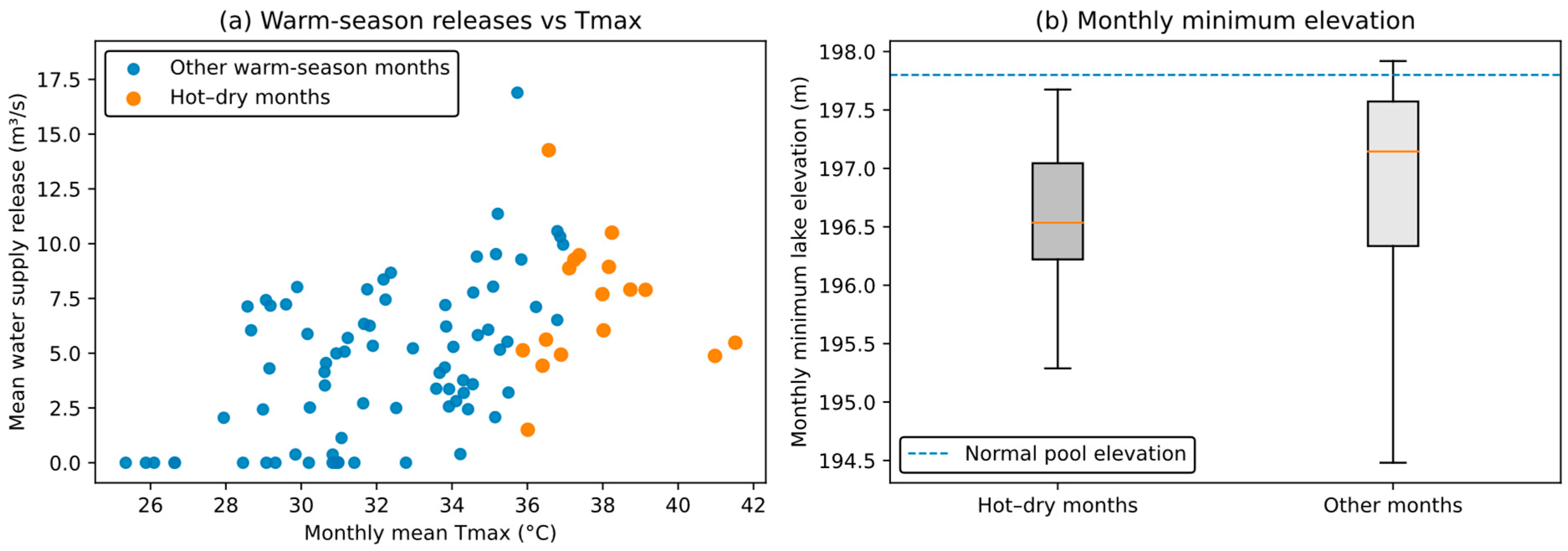

To interpret climate projections in operational terms, we quantified the climate stress metrics defined above and summarized them alongside streamflow projections. For reservoir operations, differences between hot–dry months and other months were tested using Mann–Whitney U tests, and simple regression and classification models were evaluated using standard metrics (R2 for linear models; AUC and Brier score for flood event classification).

2.7. Time Series Diagnostics of Historical Climate Inputs and Storage

The historical climate input series and the observed storage record were evaluated for trend structure, homogeneity, and multi-year fluctuations using two complementary visualization-based techniques: innovative trend analysis (ITA) [

35] and rescaled adjusted partial sums (RAPS) [

36]. The goal is not to replace the core SWAT and downscaled climate analyses, but to provide additional context on how the historical record partitions into sub-periods and to confirm that a single step change does not dominate the baseline input data.

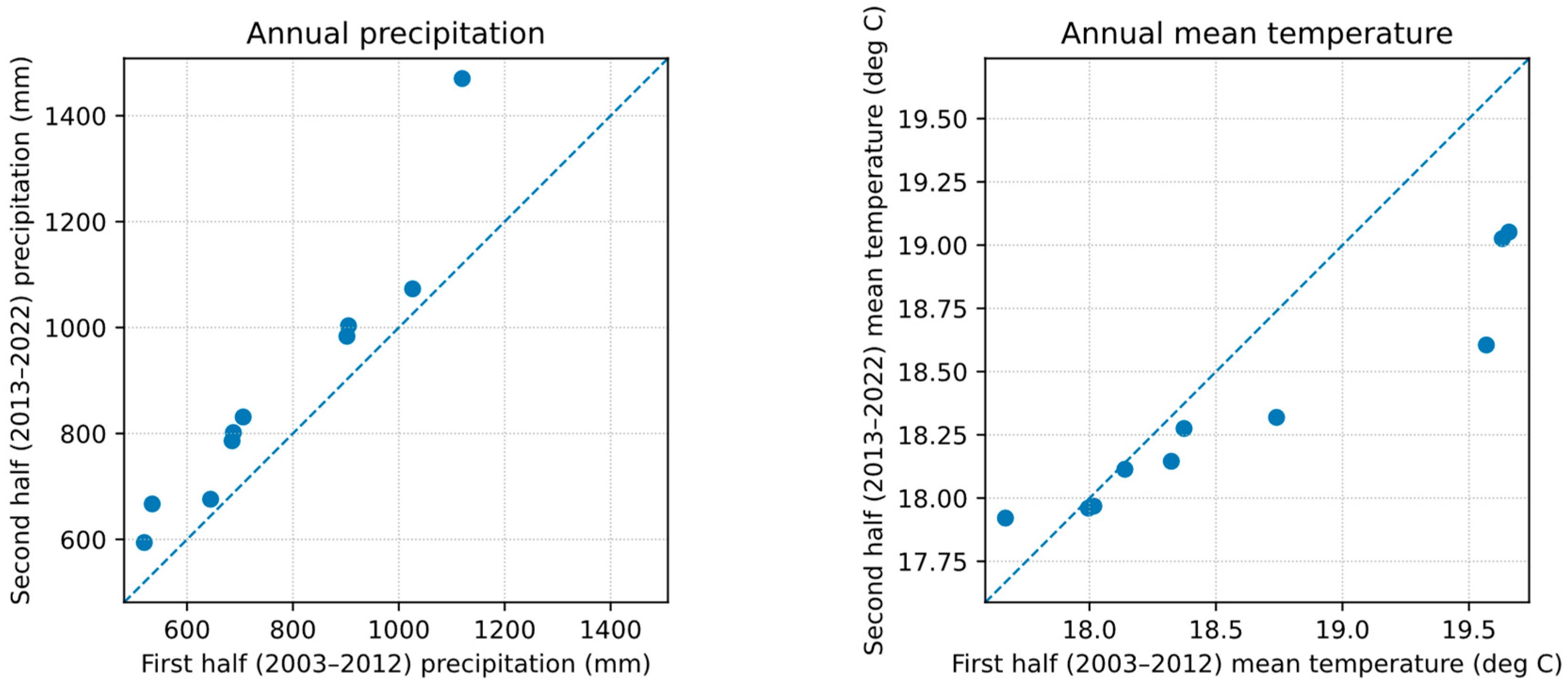

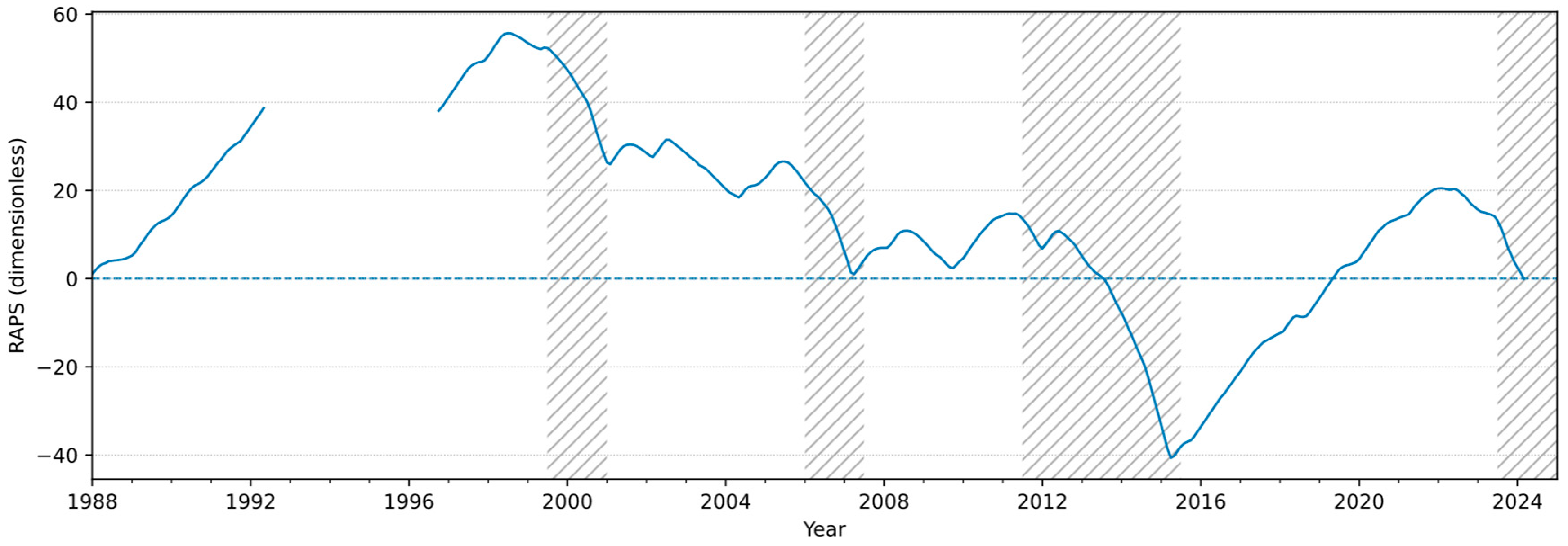

ITA was applied to annual basin-average precipitation totals and annual mean temperature derived from the seven-station baseline daily series (2003–2022). Following Sen [

35], the annual series was split into two equal sub-periods (2003–2012 and 2013–2022), each sub-series was ranked, and values were plotted against one another relative to the 1:1 line. Points consistently above (below) the 1:1 line indicate an increasing (decreasing) tendency across the distribution. To supplement the ITA visualization, time series homogeneity was also evaluated using the Pettitt nonparametric change point test [

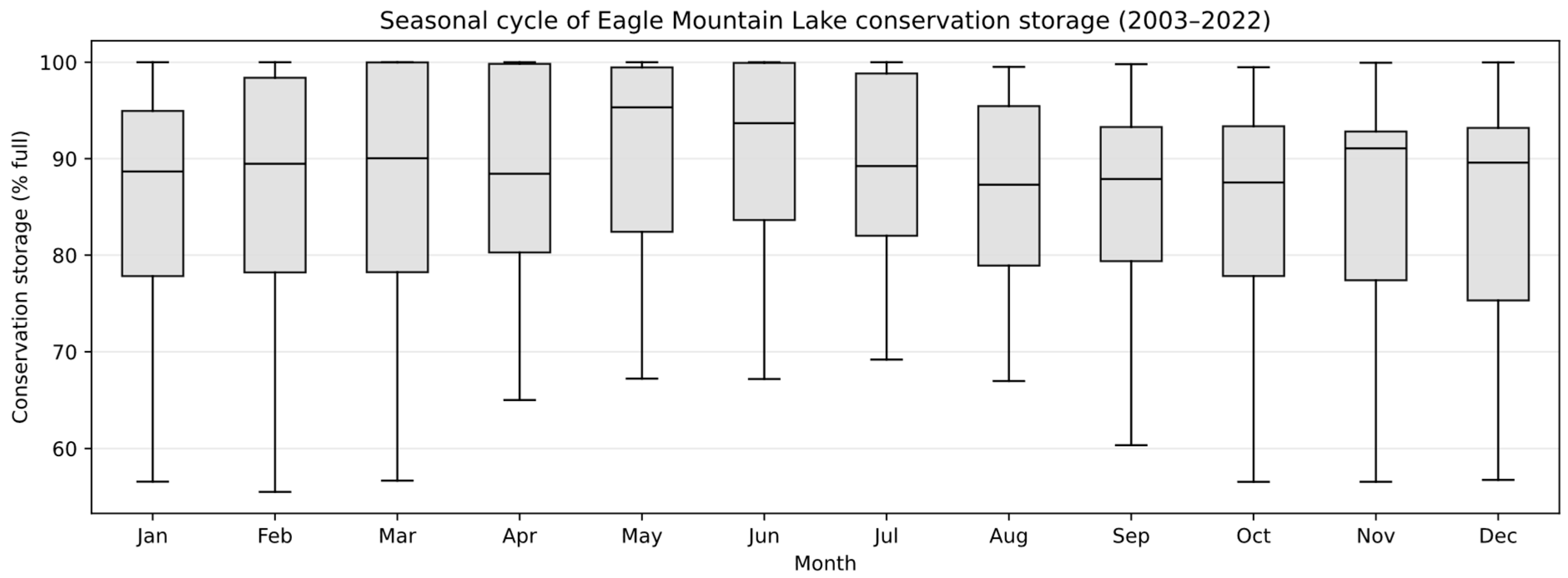

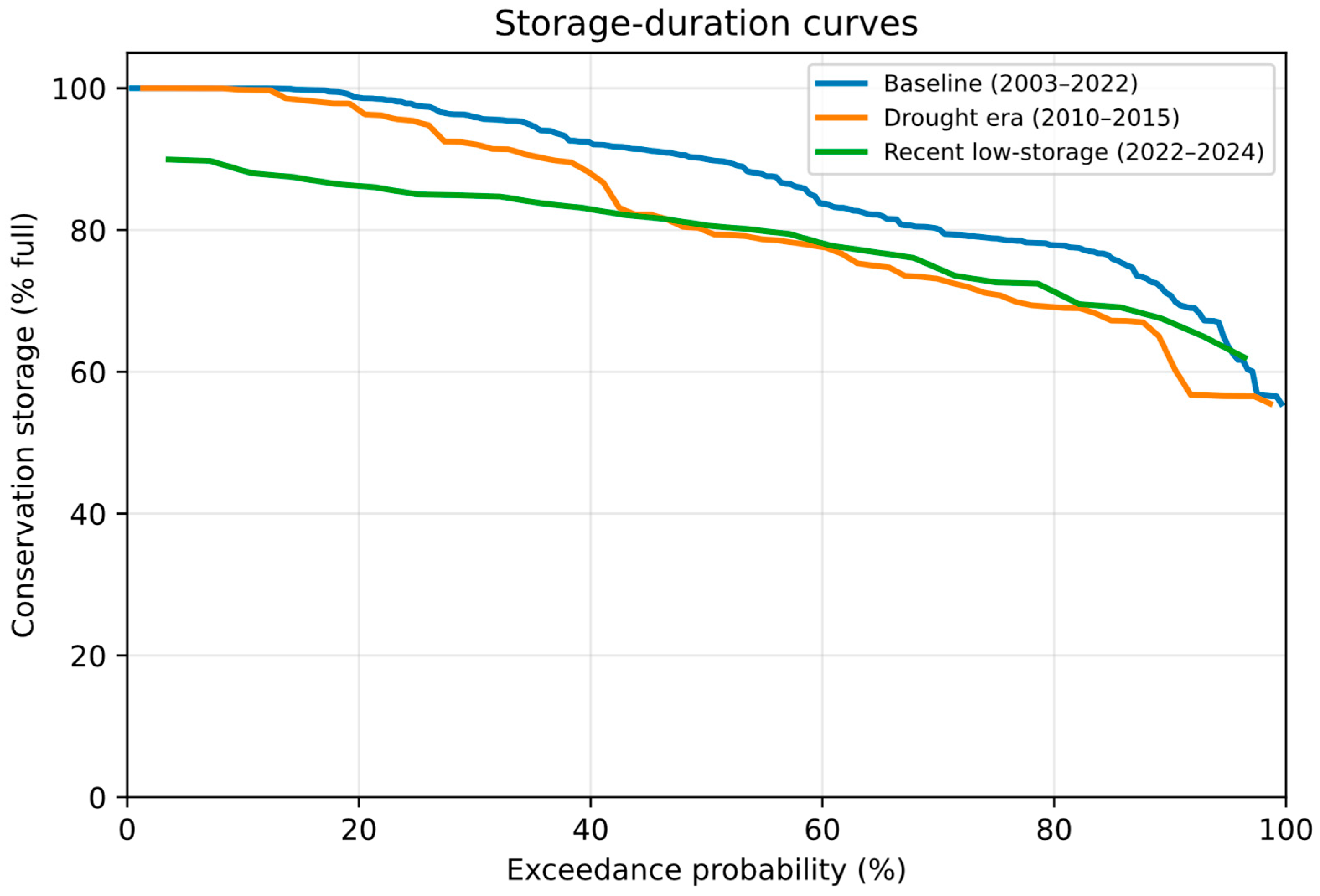

37] applied to the annual series. RAPS was applied to the observed monthly conservation storage (% full) record (1988–2024) of the Eagle Mountain Lake Reservoir. RAPS values were computed as the cumulative sum of deviations from the long-term mean, rescaled by the standard deviation, which highlights persistent departures and potential shifts in the mean state.

2.8. Reservoir Observation Analysis

Daily reservoir operations data were compiled for Eagle Mountain Lake from January 1990 to January 2022. The dataset includes (i) lake surface elevation (m), (ii) water supply release rate (m3/s), and (iii) flood discharge (m3/s; release/spill). The operations time series complements the conservation storage record used elsewhere in this study by providing direct information on release behavior and lake level dynamics.

For statistical analysis, reservoir operation variables were aggregated to monthly metrics: mean water supply release, number of flood discharge days, total flood discharge, mean elevation, and monthly minimum elevation. These monthly metrics were merged with basin-average monthly temperature and precipitation derived from the seven-station historical daily climate series for the overlapping period (2003–2021).

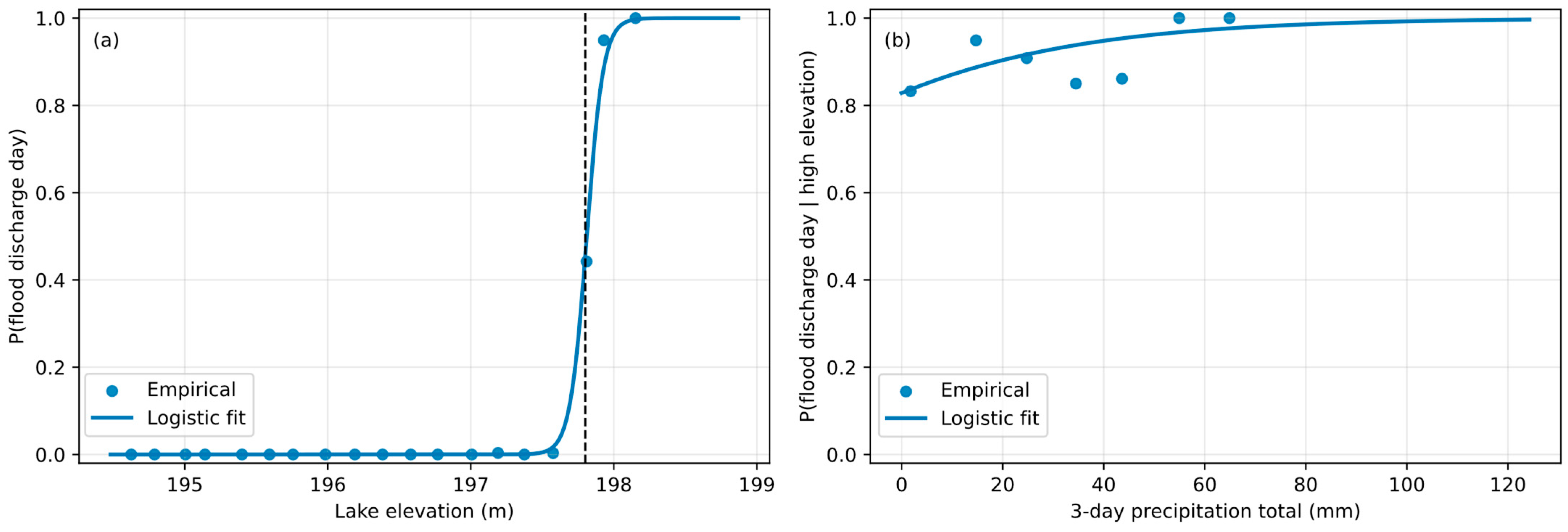

To quantify climate–operations linkages without assuming a particular operating policy model, two complementary approaches were used. Firstly, reservoir operation metrics in hot–dry months were compared with those in all other months using nonparametric tests. Secondly, for the demand season (May–September), an ordinary least squares model of monthly mean water supply release as a function of monthly mean Tmax and monthly precipitation was fitted. For flood operations, the daily occurrence of flood discharge (>0) was modeled using logistic regression with predictors representing multi-day precipitation totals and lake elevation; predictive skill was evaluated using time series cross-validation (AUC and Brier score).

2.9. Linking Projected Inflows to Reservoir Operations and Compound Event Screening

Reservoir operations respond to both seasonal timing and persistence of wet and dry conditions, rather than to annual totals alone. To translate SWAT inflow projections into management-relevant risk indicators using available observations, (i) threshold-based performance metrics from the historical conservation storage record and (ii) a screening-level storage risk relationship based on multi-year inflow deficits were combined.

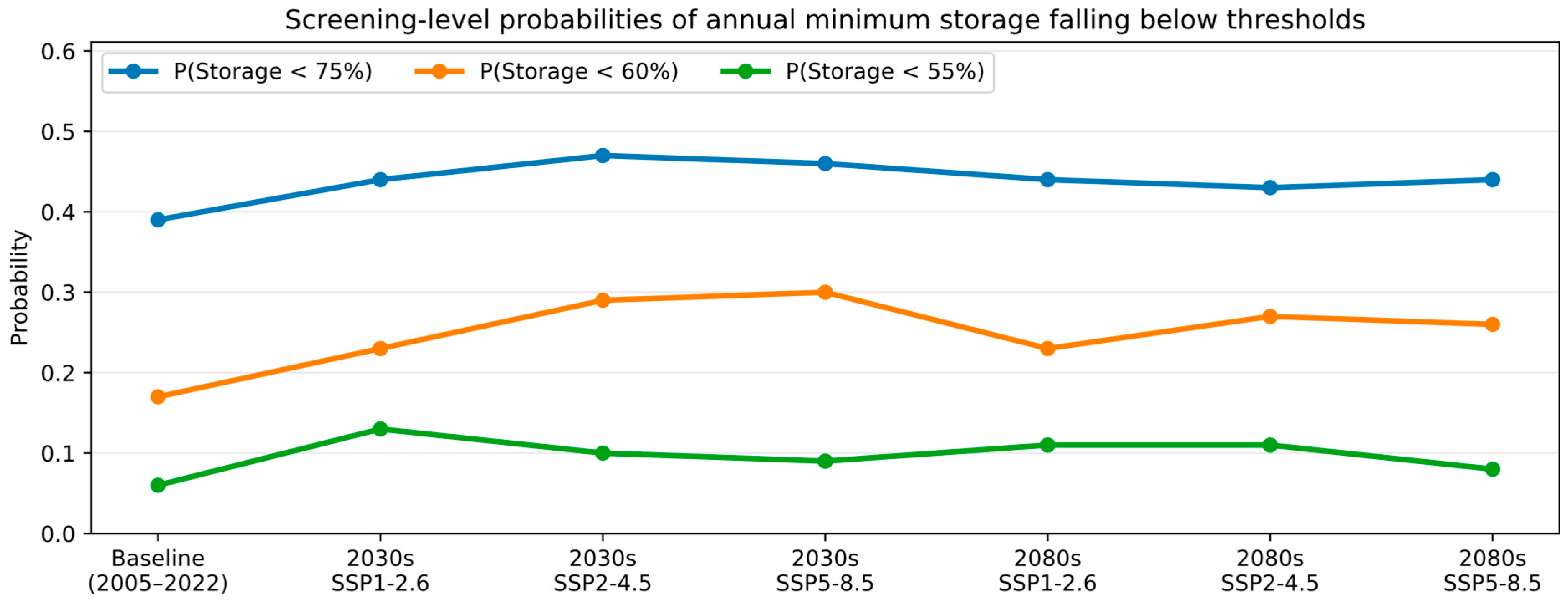

Annual inflow at the reservoir inlet was extracted from SWAT for the baseline period (2003–2022) and for each future GCM-SSP time horizon simulation. To represent multi-year drought persistence, a 3-year rolling mean inflow anomaly (Q3y) was computed. A 3-year window was selected as a compromise between capturing persistence and retaining an adequate sample size for fitting. Sensitivity checks using 2-year and 5-year rolling means produced the same monotonic relationship between sustained inflow deficits and annual minimum lake level, with only modest differences in correlation strength (r increasing from about 0.43 for 2-year to about 0.57 for 3-year and about 0.62 for 5-year). For the baseline period, Q3y values were paired with observed annual minimum conservation storage (Smin) to develop an empirical relationship between sustained inflow deficits and low-storage outcomes. Using this relationship, screening-level probabilities of annual minimum storage falling below 75% (moderate low-storage exposure), 60% (severe exposure), and 55% (approximately the minimum observed during the drought of record in the available record) were estimated for each SSP and time horizon. The 75% and 60% thresholds were chosen because they map to distinct parts of the observed distribution and operational envelope: 75% marks the onset of multi-season low-storage episodes in the historical record, whereas 60% represents rare, severe conditions that occurred only during the most extreme drought periods.

In parallel, a management-focused climate stress metric based on the downscaled daily series was quantified. A “hot–dry month” is defined as a month in which temperatures are unusually high (monthly mean Tmax above the baseline 90th percentile), and rainfall is below normal (monthly precipitation below the baseline median). Changes in hot–dry month frequency were summarized for the 2030s and 2080s across stations and GCMs, as these months coincide with peak outdoor water use and typically correspond to low inflows. Finally, the reservoir operations record (elevation, water supply releases, and flood discharge) was used to identify how hot–dry months and multi-day rainfall clusters map to distinct operating modes. This provides a direct operational bridge between projected climate conditions, SWAT inflow changes, and the observed decisions that control lake levels and downstream releases.

4. Discussion

This section synthesizes the results in the context of the study objectives: (i) evaluating SWAT performance for the Upper West Fork Trinity watershed, (ii) characterizing downscaled CMIP6 climate drivers and their uncertainty, (iii) translating those drivers into seasonal inflow shifts, and (iv) interpreting operational implications for Eagle Mountain Lake using threshold-based storage metrics and observed release/discharge responses to climate stressors.

4.1. Model Performance in Context

The calibrated SWAT model demonstrated satisfactory to good performance in reproducing observed streamflow dynamics at multiple locations within the Upper West Fork Trinity Watershed. Validation metrics for subbasin 22 (R

2 = 0.72; NSE = 0.72; KGE = 0.80) compare favorably with other SWAT applications in Texas and similar regions. Tefera and Ray [

38] reported R

2 = 0.65 and NSE = 0.61 for the Bosque watershed in North-Central Texas, while Chen et al. [

39] achieved R

2 = 0.70 and NSE = 0.79 in the Upper Mississippi River basin. The robust validation performance provides confidence in the model’s ability to analyze climate change scenarios.

The most sensitive parameters (CN2, ESCO, GW_REVAP, GW_DELAY, and related groundwater recession terms) are consistent with many SWAT applications in Texas and other semi-humid, mixed land use basins. Runoff sensitivity to CN2 and soil/evaporation parameters reflects the importance of infiltration-excess runoff and evapotranspiration partitioning, while sensitivity to groundwater parameters reflects the role of shallow aquifer storage in sustaining baseflow during dry periods. Similar sensitivity patterns have been reported for SWAT-based climate impact studies in Texas, including the Bosque watershed and other regional basins [

38,

40]. These consistencies provide confidence that the calibrated parameter set reflects plausible process controls rather than compensating errors.

4.2. Climate Projections and Uncertainty

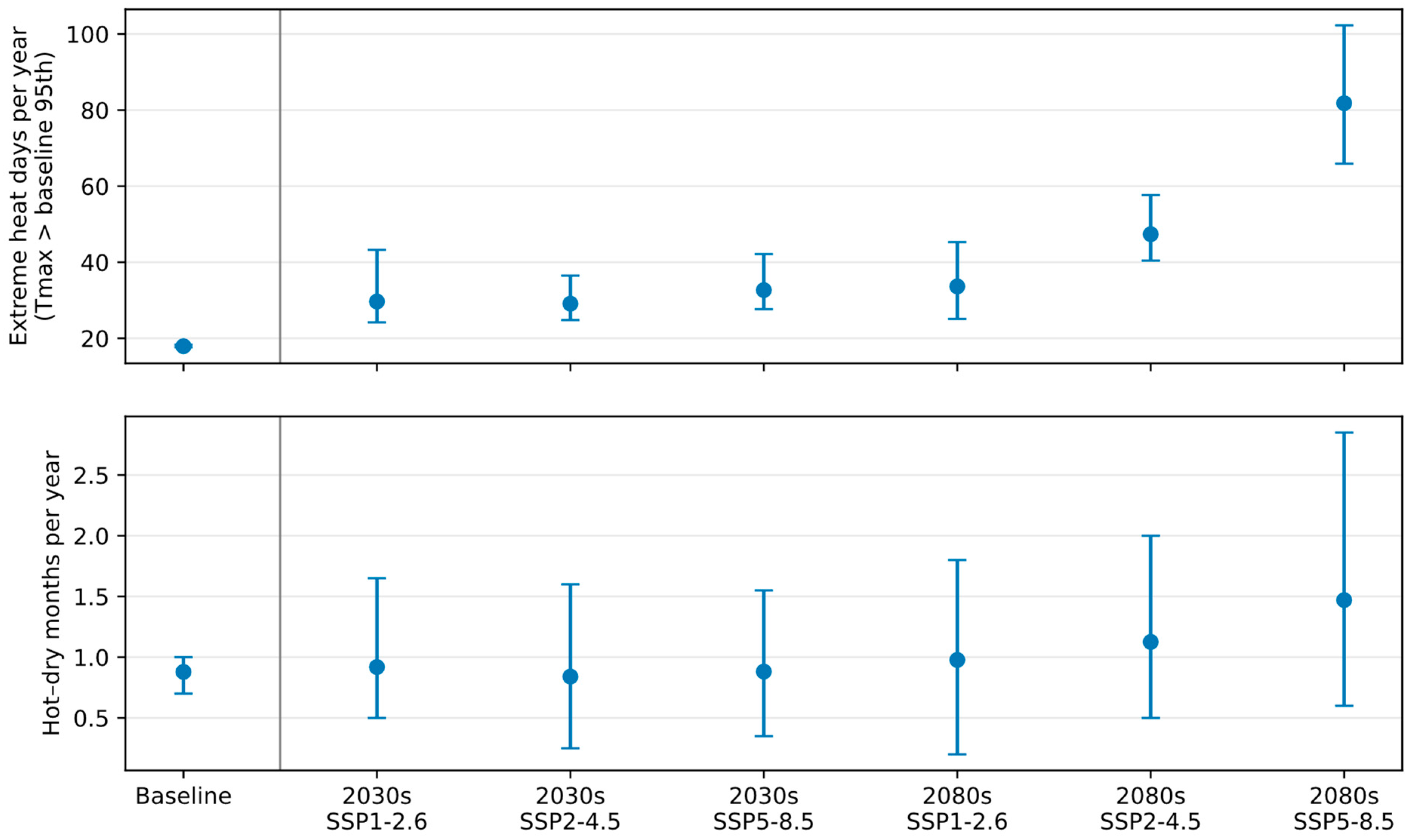

The downscaled daily series showed a robust warming signal across all stations and GCMs. Relative to 2003–2022, mean annual temperature increased by 0.7–1.9 °C by the 2030s and by 0.7–6.1 °C by the 2080s, depending on SSP (

Table A6). Importantly for operations, warming is not only reflected in a higher mean but also in many more very hot days: days above the historical 95th percentile increased from ~18 yr

−1 to ~30–33 yr

−1 in the 2030s and to ~34–82 yr

−1 in the 2080s (

Figure 11).

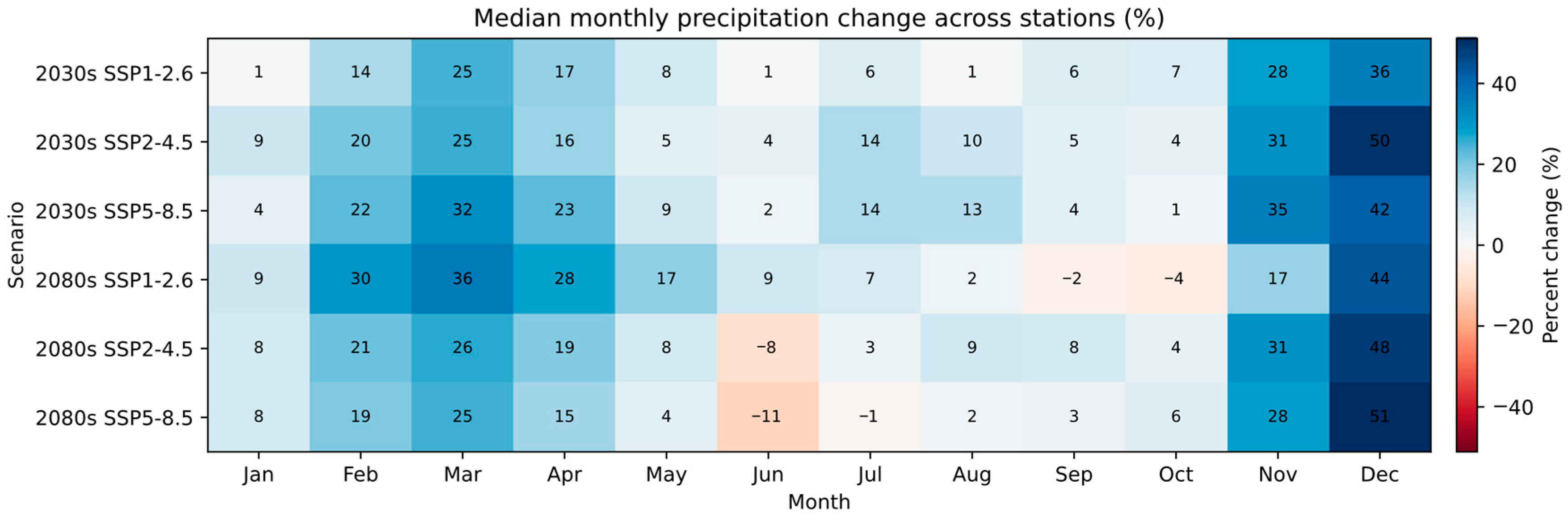

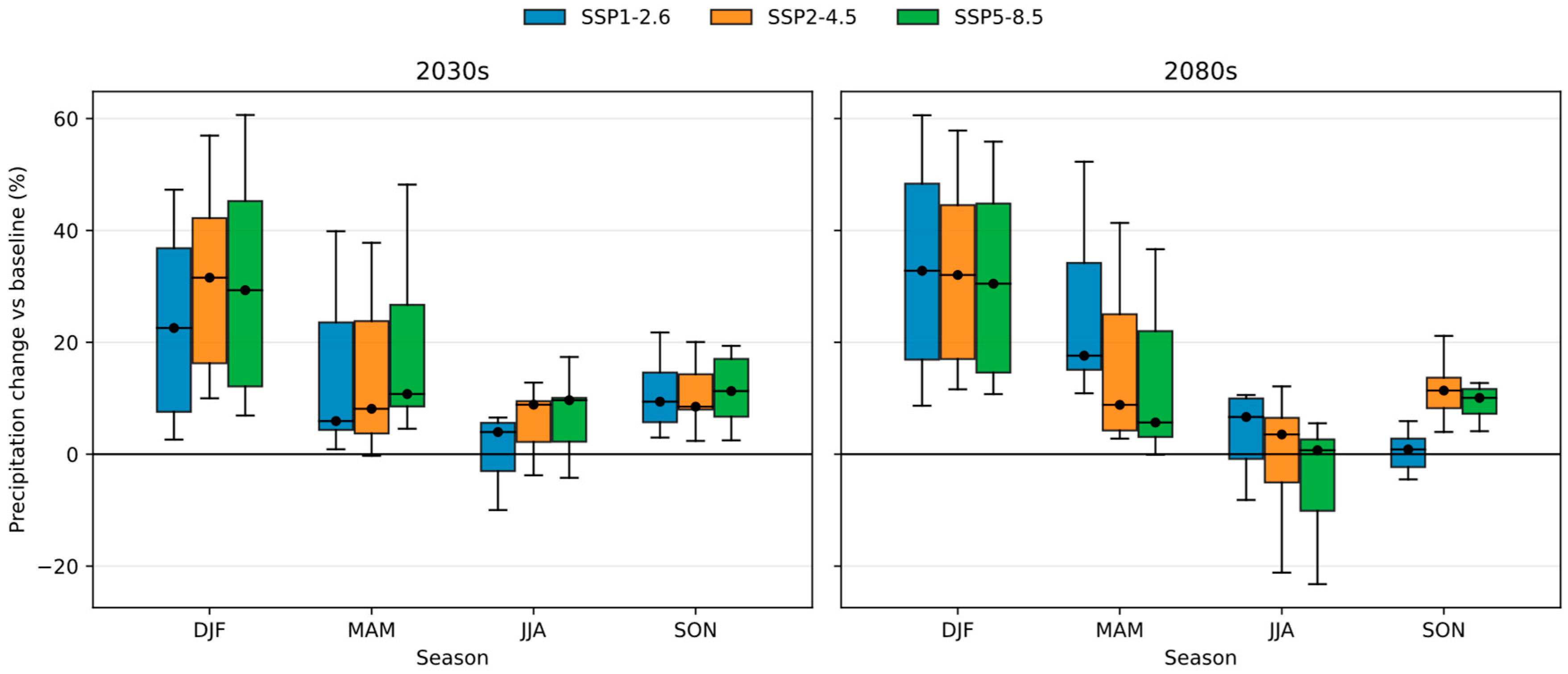

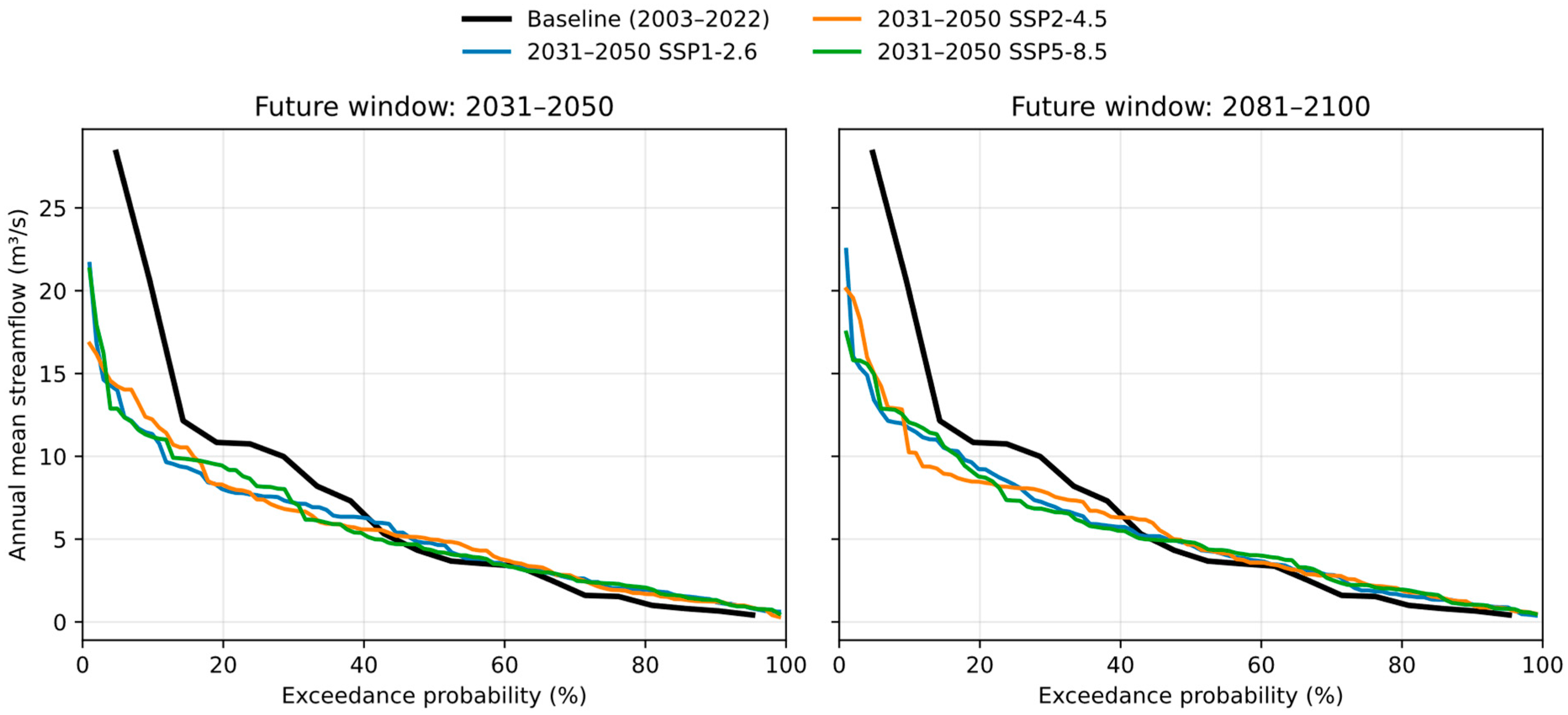

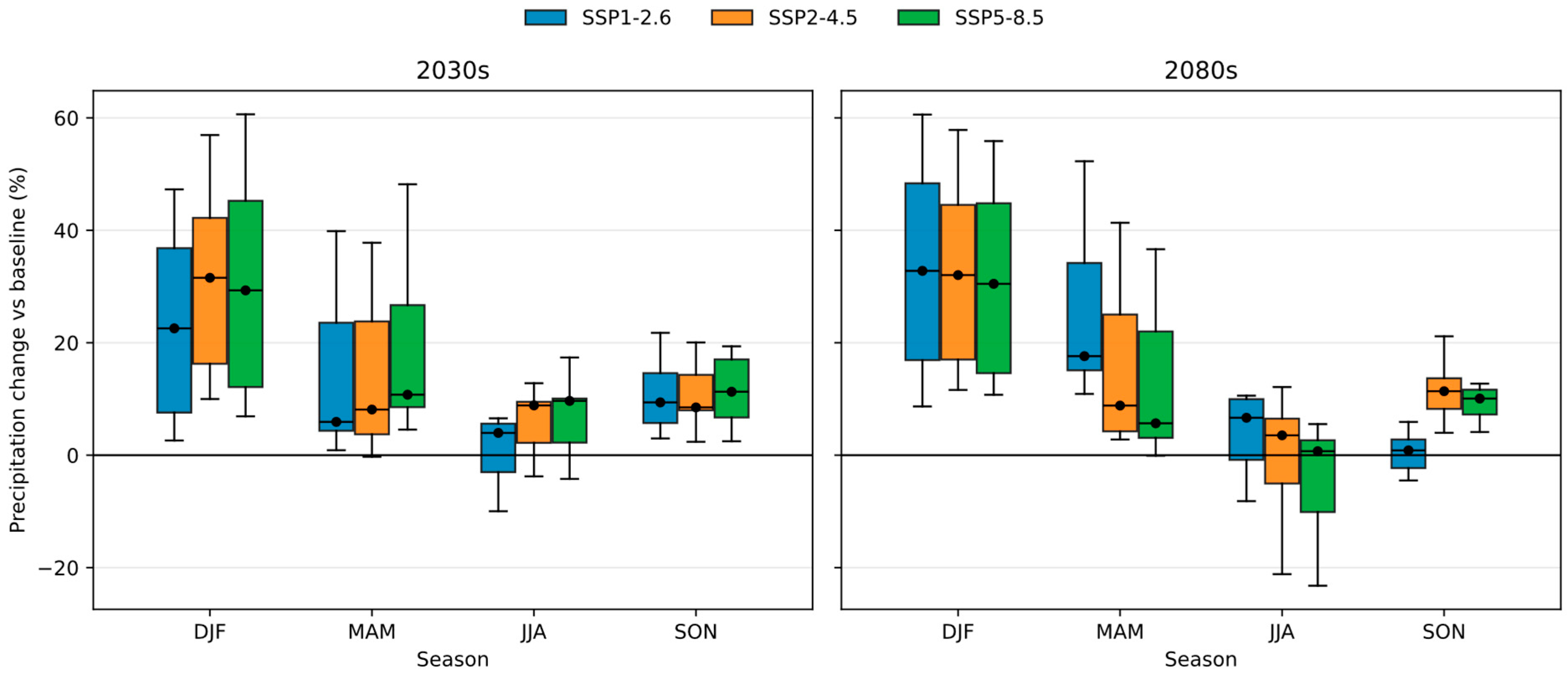

Precipitation projections remained more uncertain than temperature. The ensemble median indicated modest increases in mean annual precipitation (~10–14%), but the full range spans decreases of ~10–24% and increases up to ~55% (

Figure 4;

Table A7). This uncertainty matters because relatively small changes in rainfall timing and intensity can translate into larger changes in runoff generation and seasonal refill, particularly when paired with higher evaporative demand in a warmer atmosphere.

4.3. Streamflow Response Mechanisms

The projected decline in annual streamflow despite modest increases in mean annual precipitation in some scenarios indicates that warming-driven increases in evaporative demand can dominate the water balance. The temperature signal was robust across stations and GCMs (

Figure 4b), and higher temperatures increase potential evapotranspiration and reduce effective precipitation available for runoff generation, particularly during the warm season. Accordingly, precipitation variability alone is insufficient to explain simulated flow reductions; the combined influence of warming, longer growing seasons, and higher atmospheric demand provides a physically consistent explanation for reduced runoff efficiency.

The seasonal redistribution of streamflow, with enhanced reductions in spring–summer and potential increases in late summer–fall, reflects the projected changes in precipitation seasonality combined with temperature-driven evapotranspiration dynamics. Spring streamflow reductions of up to 80% (June under SSP1-2.6) would substantially impact the primary reservoir recharge period, potentially leading to critically low water levels during subsequent summer demand peaks. Conversely, projected late-summer and fall increases (>250% in August under some scenarios) could increase flood risk while providing limited water supply benefit if reservoir storage is already depleted.

4.4. Comparison with Regional Studies

The projected streamflow reductions in the Upper West Fork Trinity watershed are broadly consistent with recent Texas-focused and southern Great Plains studies that emphasize increasing evaporative demand and more persistent drought risk under warming. For example, drought risk assessments for multiple Texas reservoirs have shown that storage outcomes can diverge across climate models and that explicitly tracking critical storage thresholds improves interpretability for planning [

41]. At the basin scale, SWAT-based work in the Trinity River basin has similarly highlighted the value of process-based simulations for interpreting future streamflow drought behavior under changing climate forcing [

42].

Nationally, the magnitude and direction of projected inflow changes align with broader evidence that many U.S. reservoirs will experience reduced inflows and increased hydroclimatic stress as temperatures rise [

43]. The seasonality signal identified here, with larger reductions during the spring refill period and higher relative variability in late summer, is also consistent with studies across the Southwest and southern Great Plains that project earlier and less reliable runoff generation under warming, even when precipitation changes are uncertain [

17,

44].

4.5. Implications for Water Resource Management

The projected 17–20% reduction in average annual streamflow, combined with a marked increase in extreme heat days and more frequent hot–dry months, has direct implications for future reservoir operations at Eagle Mountain Lake. SWAT results indicated reduced spring refill (March–June), whereas daily climate projections indicated that hot conditions would intensify during the warm season. Because observed operations indicated that hot–dry months coincided with roughly twice the mean water supply release and lower minimum lake levels (

Section 3.7), these climate shifts would increase the likelihood of warm-season drawdown and tighter operating margins even if operating rules remain unchanged.

Firstly, enhanced storage and capture infrastructure could maximize the retention of projected increases in late-summer and fall streamflow. Upgrades to intake structures, spillway capacity, and pumping systems could enable rapid response to episodic high-flow events that may occur more frequently under climate change scenarios. From a flood operations perspective, the projected late-summer inflow increases imply that the period requiring available flood storage and rapid release capacity may extend into July–September. Under the scenario with the largest late-summer increases (2030s SSP5-8.5), the ensemble mean July–September inflow volume would be approximately 3.7 × 107 m3 higher than baseline, about 15% of the reservoir’s conservation storage. Although these estimates are based on mean monthly inflows and do not represent peak event flows, they indicate a higher likelihood that a small number of intense storms could rapidly raise the pool elevation and trigger flood releases if the reservoir is near normal pool elevation. Practically, this supports (i) maintaining seasonal flood buffer space later into summer, (ii) prioritizing forecast-informed pre-releases when heavy rainfall is expected and the pool is elevated, and (iii) revisiting downstream release constraints and spillway/outlet capacities to ensure safe routing of late-summer storm clusters.

Secondly, demand management and conservation programs will become increasingly critical as supply margins narrow. The DFW region has already achieved per-capita water use reductions (541 L/day vs. the state average of 587 L/day), and further conservation, particularly in outdoor irrigation, which accounts for 27% of urban use, could substantially buffer against projected supply reductions. Thirdly, diversification of water supply sources through enhanced conjunctive use of surface and groundwater, water reuse and recycling, and interbasin transfer agreements could reduce vulnerability to disruptions in single-source supply. The Texas 2022 State Water Plan identifies multiple regional water supply strategies that could complement the supply of Eagle Mountain Lake under future climate conditions. Fourthly, updated reservoir operating rules that account for changes in seasonal streamflow patterns could improve water supply reliability. Current operations, developed under historical climate conditions, may require revision to optimize storage and releases in response to projected seasonal shifts in inflow timing and magnitude.

Finally, communicating risk in operational terms is as important as the hydrologic signal itself. The “hot–dry month” framing translates climate projections into the months that matter most for managers, periods with peak demand and typically low inflows, and the operations record confirms that these months are associated with higher releases and lower lake levels. In parallel, flood discharges occur primarily when lake levels are near or above normal pool and after multi-day rainfall clusters (AUC = 0.99), underscoring that future operations will need to balance refill and drought protection against maintaining flood buffer. Together, these results support drought triggers and rule curve reviews that account for both seasonal timing shifts and persistence of hot, dry conditions.

4.6. Storage Reliability Implications from Reservoir Observations

Reservoir observations provide a practical lens for interpreting the projected inflow changes. The 2010–2015 Texas drought produced the longest and deepest drawdown in the 1988–2024 record, including 20 months below 75% storage and a minimum of about 54% full. These durations are operationally critical because they span multiple high-demand seasons and reduce flexibility for meeting competing water supply and recreational objectives.

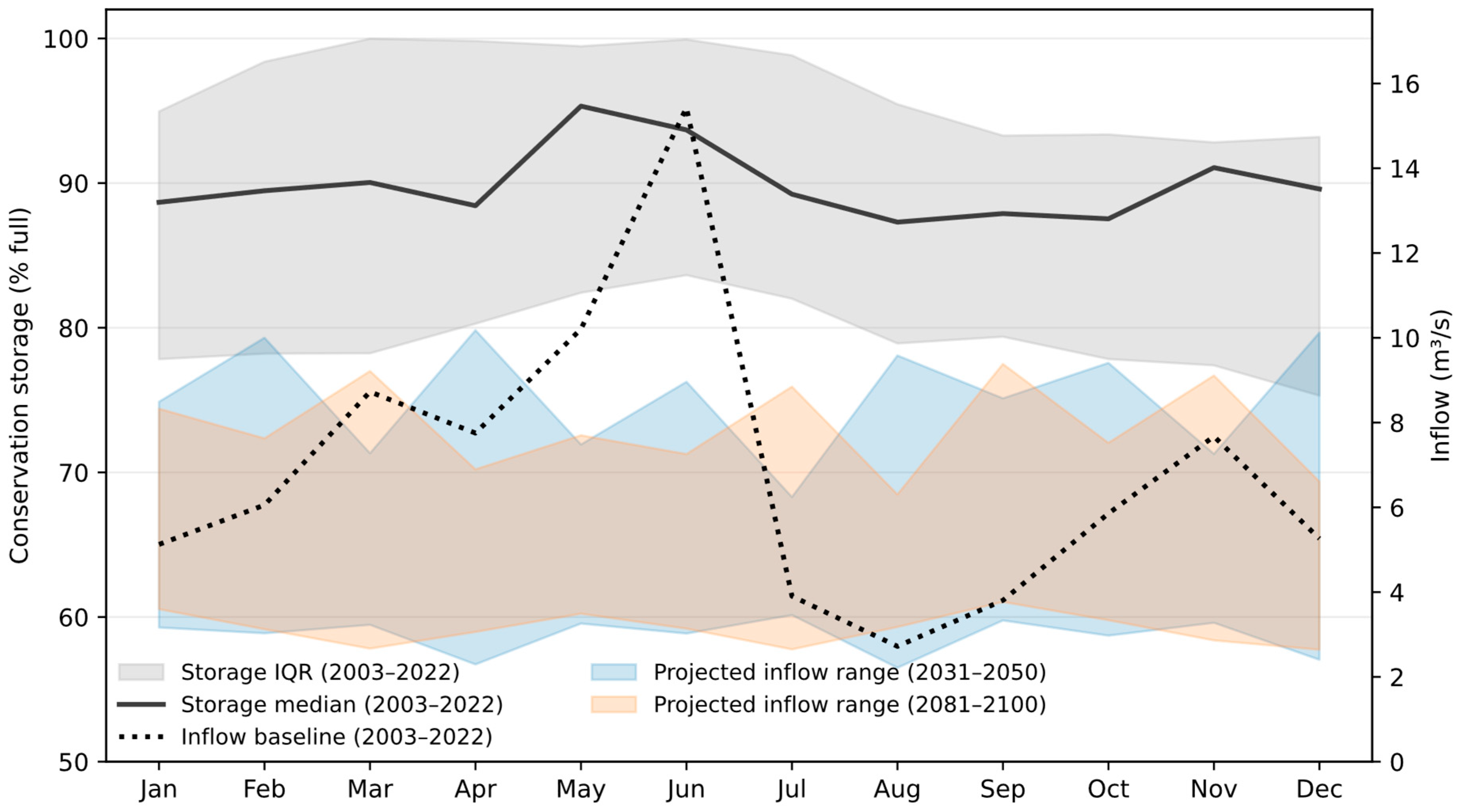

Projected inflow reductions would be largest in March–June, which coincides with the period when the reservoir most often reaches its annual maximum and refills from watershed inflows (

Figure A8). This seasonal alignment suggests that changes in inflow timing can increase the persistence of late-summer low-storage levels unless offset by operational adjustments (e.g., revised release rules, drought-stage demand reductions, increased reuse, or additional interconnections). Although this study does not simulate reservoir operations, the threshold metrics reported here provide transparent benchmarks (75% and 60% storage) that can be used to evaluate future reservoir performance once SWAT inflow projections are coupled to an operations model.

The screening-level storage risk emulator developed here provides a transparent method for translating inflow projections into storage outcomes, using observed behavior as a benchmark. Although it does not replace an explicit reservoir operations model, it captures a key operational reality: minimum storage is strongly associated with sustained inflow deficits over multiple years. Under both mid-century and late-century horizons, the projected inflow distributions imply higher probabilities of severe low-storage years (S

min < 60%) than the historical baseline (

Table 5), even when mean annual precipitation does not decline consistently across models.

This approach also supports “stress testing” that is directly actionable. For example, utilities can interpret the probabilities in

Figure 10 as the likelihood of entering restriction-relevant storage zones under unchanged operations and demand. When combined with the compound hot–dry month lens (hot conditions plus below-normal rainfall), the results indicated a higher risk of demand–supply mismatch in the warm season: storage refilled less during spring and then faced higher evaporative and demand pressures during summer. These dynamics motivate adaptive rule curves, enhanced conservation, and diversified supply portfolios designed for persistence-driven drought rather than isolated low-flow years.

4.7. Study Limitations and Future Research

Some limitations should be considered when interpreting these results. Firstly, potential evapotranspiration was estimated using the Hargreaves method because humidity, wind speed, and solar radiation data were not consistently available across stations. Although a sensitivity check indicated modest effects on simulated streamflow, using the Penman–Monteith method where feasible would reduce uncertainty in warm-season water balance estimates. Secondly, land cover was held constant and therefore does not represent projected land use change in the rapidly urbanizing Dallas–Fort Worth region, which could alter runoff generation, infiltration, and baseflow. Thirdly, the analysis emphasized annual and monthly statistics to support long-term planning, which may not fully capture short-duration extremes and persistence (e.g., multi-day flood-producing storms or multi-week hot–dry spells) that drive operational stress. Fourthly, future reservoir storage and releases were not simulated using an explicit reservoir mass balance model and operating policy, and potential changes in human water use (demand growth, irrigation practices, groundwater pumping) were not explicitly represented. A mid-century 2051–2080 window was not analyzed because the downscaled daily forcing series generated for this study covered 2031–2050 and 2081–2100; adding 2051–2080 would require regenerating the downscaled series and rerunning the SWAT ensemble, which is identified as a priority extension.

Future research should: (i) quantify daily extremes and compound event metrics directly from the downscaled daily station series, including frequency and persistence of “hot–dry” months (e.g., Tmax above the baseline 90th percentile and precipitation below the baseline median) and related run-length/clustering metrics; (ii) couple climate-conditioned SWAT inflows to a reservoir operations model (rule curve simulation and/or optimization) to evaluate storage reliability, drought trigger performance, and tradeoffs among water supply, flood risk reduction, recreation, and environmental objectives; (iii) incorporate demand growth, improved lake surface evaporation estimates under warming, and land use change scenarios; and (iv) broaden the uncertainty envelope using additional GCMs and alternative downscaling methods. Operations-focused extensions would benefit from additional data, such as daily releases (separating flood discharge and water supply releases), withdrawals, interconnection, diversion flows, and lake surface precipitation and evaporation.

5. Conclusions

By integrating a calibrated SWAT watershed model, station-scale downscaled CMIP6 daily climate projections, and a multi-decadal record of Eagle Mountain Lake storage and operations, this study translated climate-driven hydrologic change into indicators that are directly interpretable in reservoir management terms. The analytical framework emphasized three critical dimensions of climate–reservoir interactions: (i) seasonality, particularly the contrast between spring refill dynamics and warm-season drawdown patterns; (ii) persistence, focusing on multi-year inflow deficit sequences rather than isolated annual anomalies; and (iii) operational triggers, including hot–dry month conditions associated with elevated demand and rainfall clustering events linked to flood discharge protocols. Key takeaways are summarized as follows:

- (1)

Projected hydroclimatic signal: Downscaled CMIP6 projections indicated robust warming across the watershed (about +0.7 to +1.9 °C in 2031–2050 and about +0.7 to +6.1 °C in 2081–2100 across scenarios), while mean annual precipitation changes remained uncertain and model-dependent.

- (2)

Projected inflow change: SWAT simulations forced by the downscaled series indicated a consistent decline in mean annual inflow (about 17–20%), with the largest reductions concentrated in the spring refill season (March–June).

- (3)

Storage risk implication: When inflow deficits persisted for multiple years, the historical record showed that the reservoir is more likely to enter extended low-storage episodes; screening results based on multi-year inflow anomalies indicated a higher future likelihood of crossing 75%, 60%, and 55% storage thresholds under unchanged demand and operating conditions.

- (4)

Operational relevance of hot–dry months and rainfall clusters: Hot–dry months coincided with higher water supply releases and lower minimum lake levels, whereas flood discharges occurred primarily near or above normal pool and after multi-day rainfall clusters. Increasing extreme heat days and more frequent hot–dry months, therefore, tightened the operational margin between refill, summer demand, and flood readiness.

Collectively, these results indicate that the most consequential climate signal for Eagle Mountain Lake is not only “how much” inflow changes, but “when” inflow arrives and “how persistent” deficits become, because these factors govern refill reliability and the likelihood of entering storage zones associated with multi-month drawdowns. The management-oriented indicators used here (seasonal refill sensitivity, persistence-based storage risk screening, and hot–dry/rainfall cluster operational triggers) are intended as transparent, decision-relevant diagnostics; a logical next step is coupling the climate-conditioned inflow ensembles to an explicit reservoir mass balance/operations model (including demand growth and improved evaporation representation) to evaluate alternative drought triggers, rule curves, and integrated drought–flood operating strategies.