Development of an Agricultural Water Risk Indicator Framework Using National Water Model Streamflow Forecasts

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

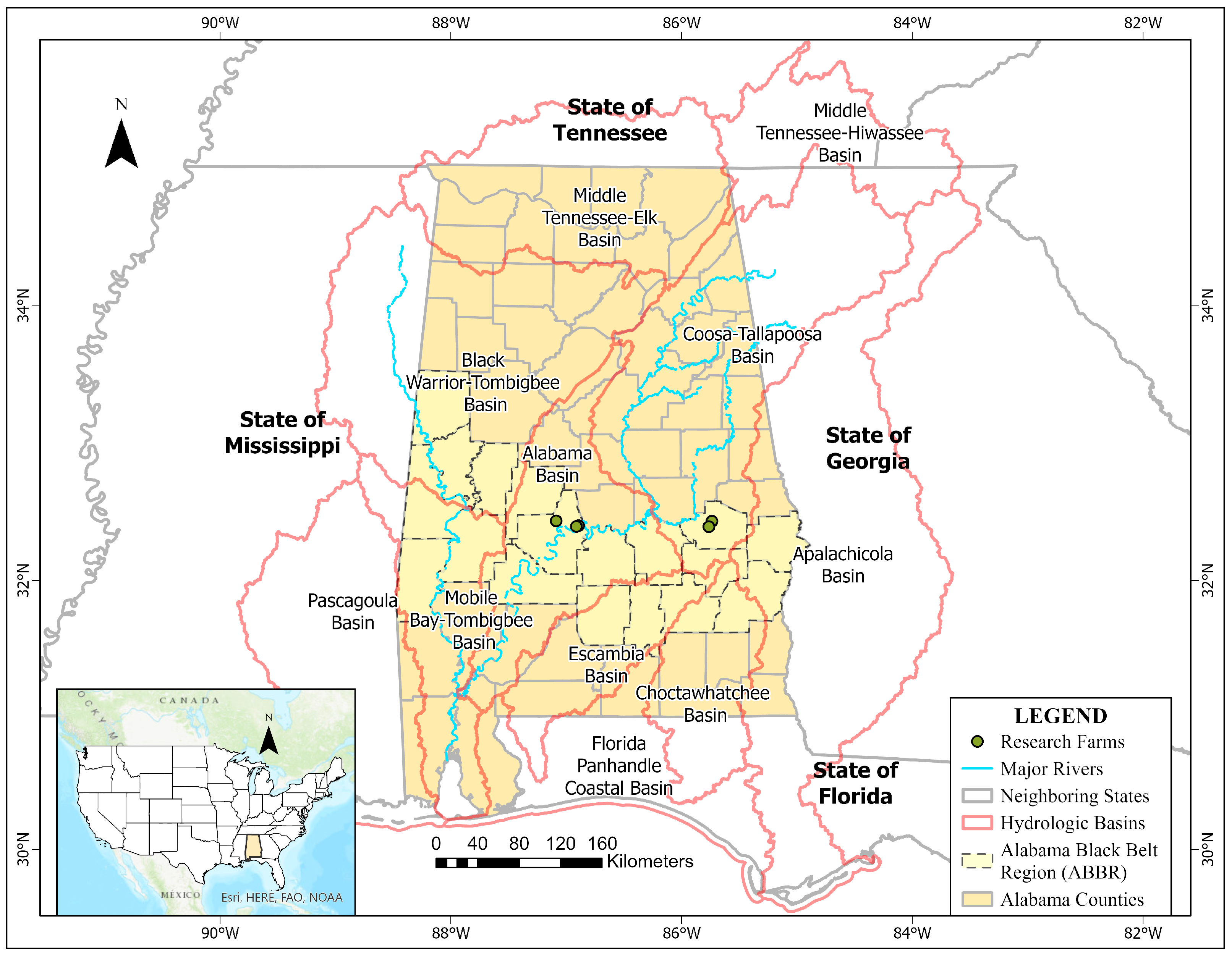

2.1. Study Area

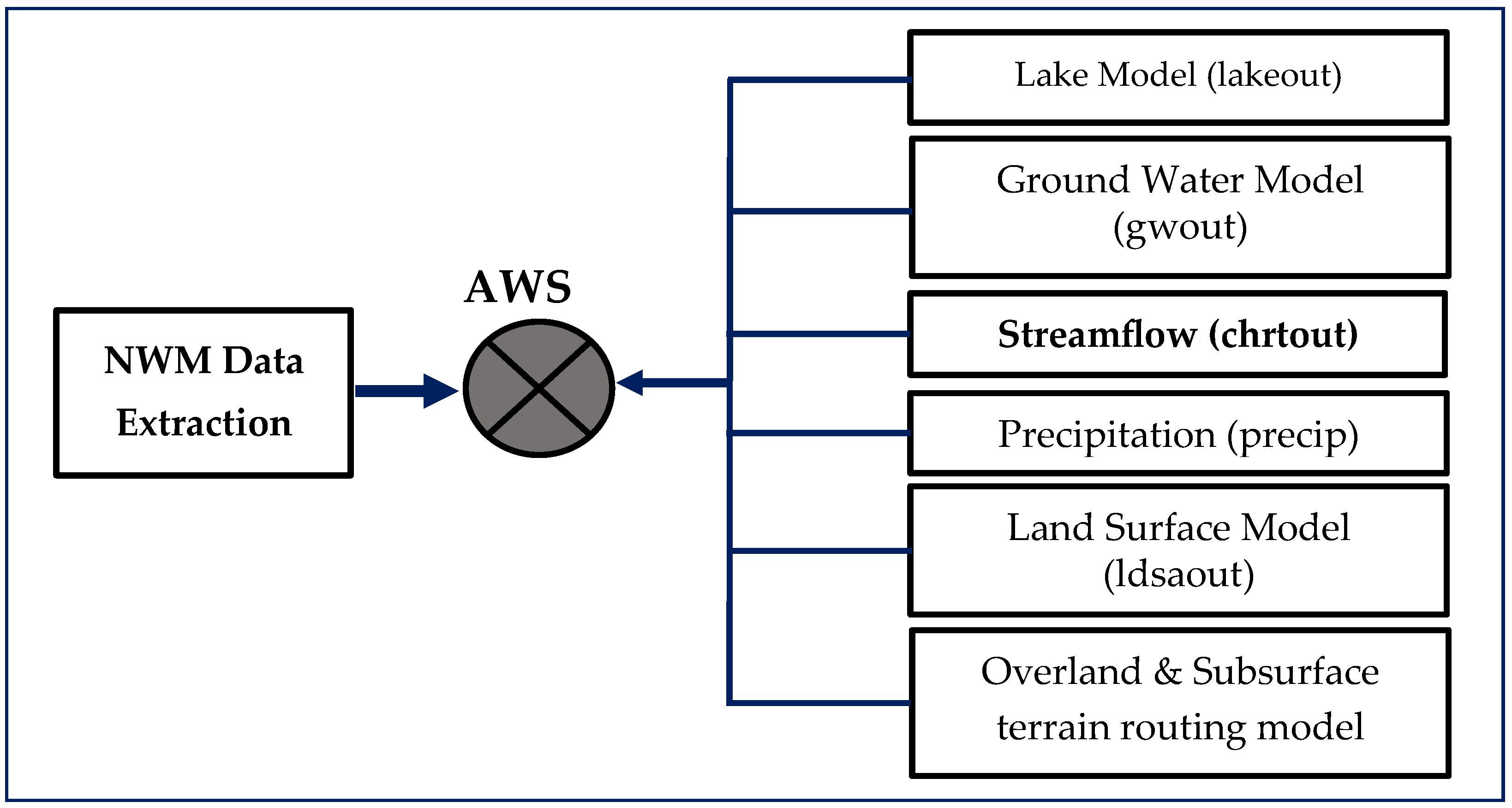

2.2. Overview of the National Water Model (NWM) and Its Use in This Study

2.3. Retrospective Streamflow Data and Baseline Threshold Development

2.4. NWM Forecast Retrieval and Preprocessing Pipeline

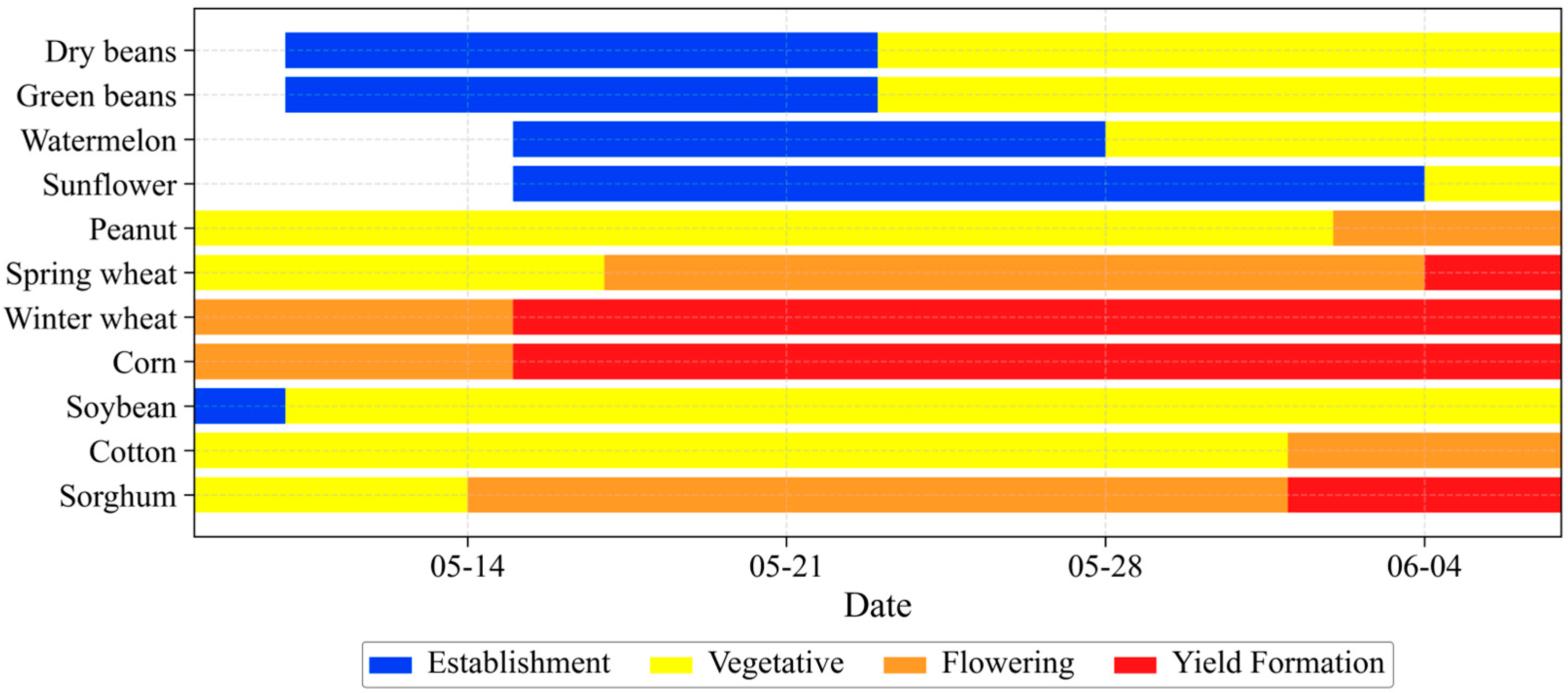

2.5. Crop Variable Characterization

2.6. AWRI Framework and Scoring System

2.6.1. Exposure: B1—Coefficient for Hydrological Threat Classification

2.6.2. Sensitivity: B2—Coefficient for Crop Tolerance to Stress Conditions

2.6.3. Adaptive Capacity: B3—Coefficient for Resilient Measures

2.6.4. Composite Classification and Implementation Workflow

3. Results

3.1. Farm-Level Streamflow Mapping for AWRI Evaluation

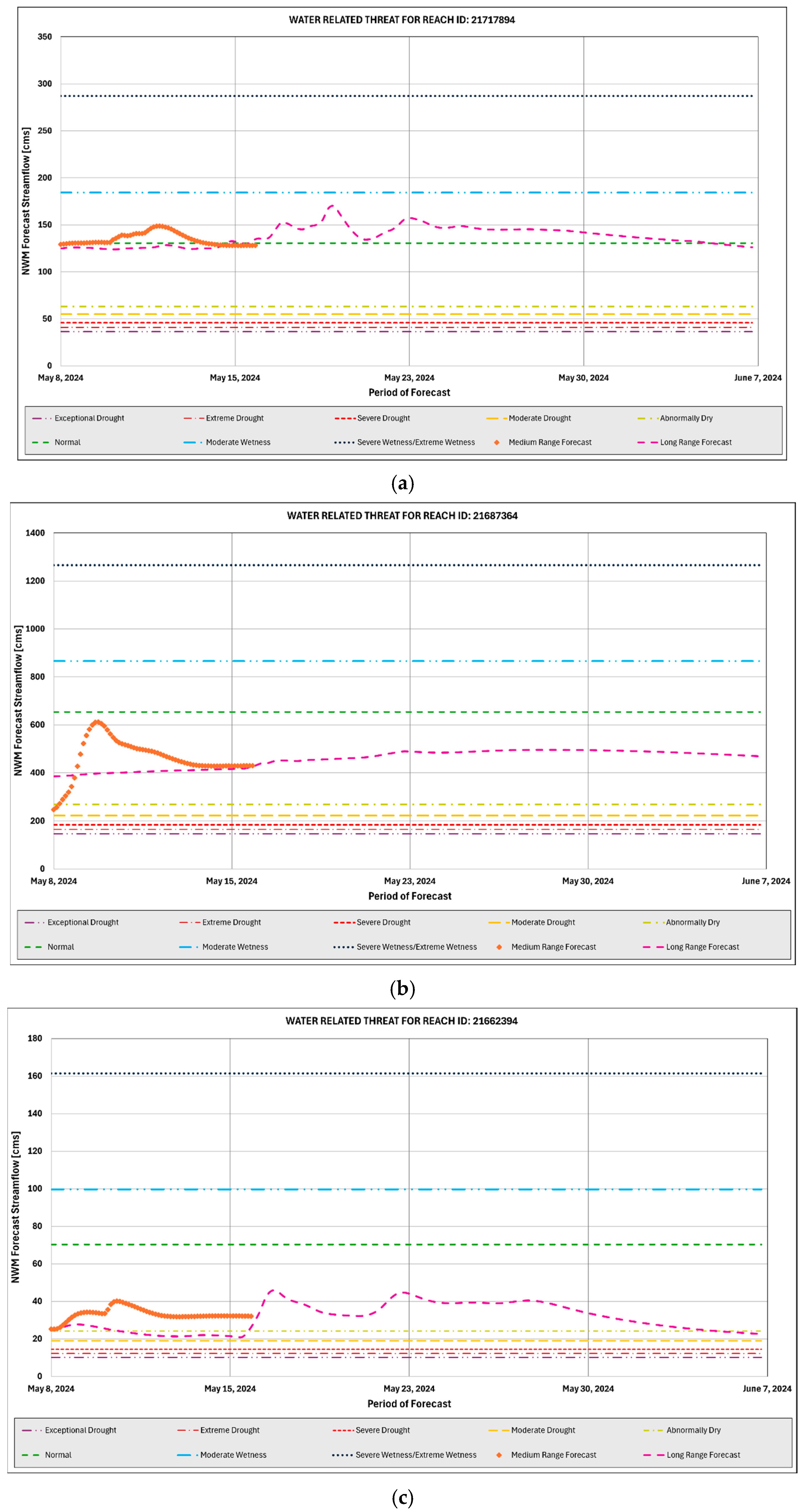

3.2. Streamflow Characterization for B1 Scoring

3.3. AWRI Scoring Example Across Reach IDs and Forecast Scenarios

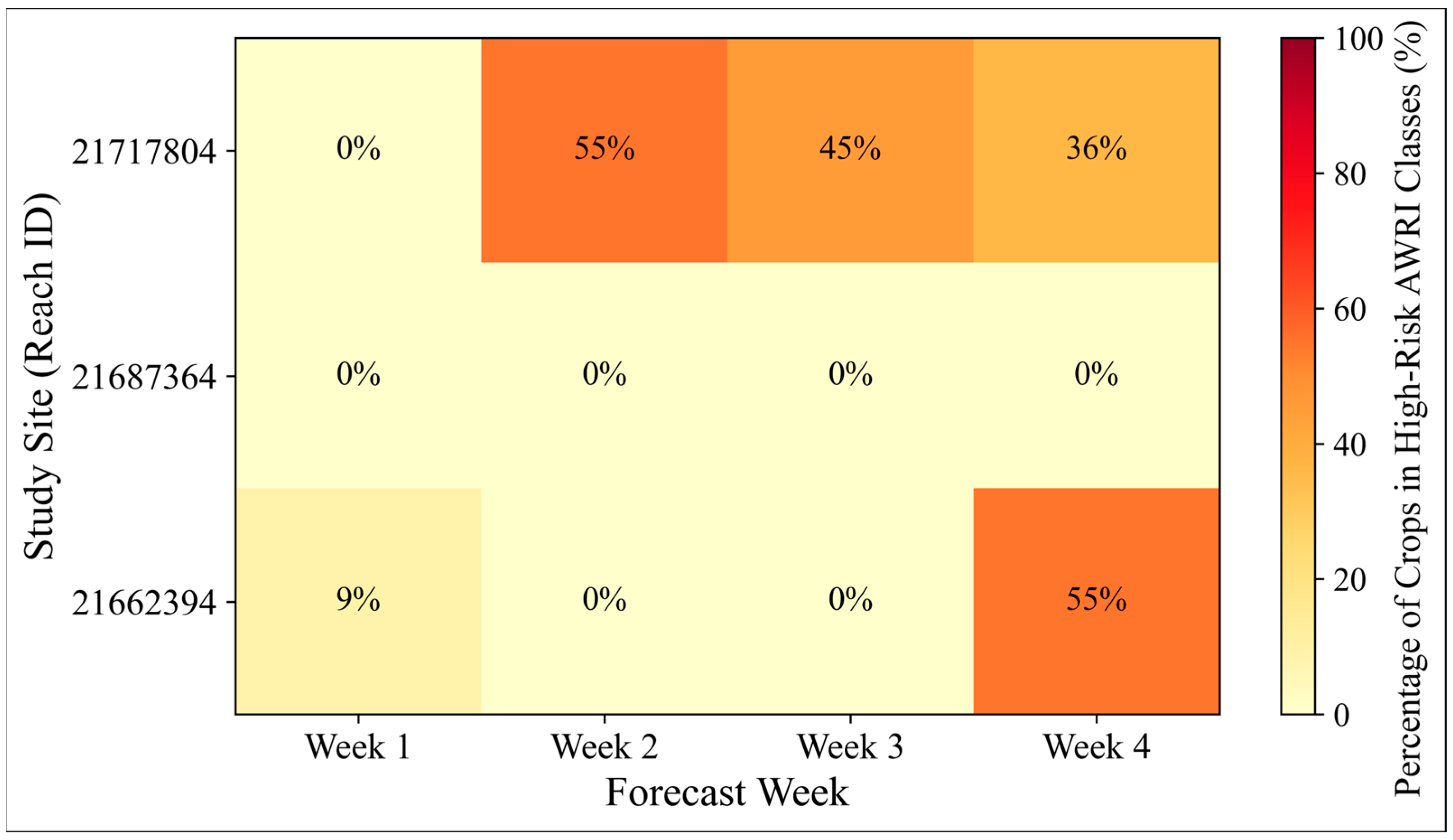

3.4. AWRI Forecast Outcomes Across Study Sites (Medium and Long Range)

3.4.1. Reach ID 21717804 (Blueberry Farm and Tuskegee University Organic Farm)

3.4.2. Reach ID 21687364 (Brown and Smith Farm)

3.4.3. Reach ID 21662394 (BBMC Selma Farm)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ABBR | Alabama Black Belt Region |

| AWRI | Agricultural Water Risk Indicator |

| HAND | Height Above Nearest Drainage |

| HRRR | High-Resolution Rapid Refresh |

| LSM | Land Surface Model |

| MPE | Multisensor Precipitation Estimator |

| MRMS | Multi-Radar/Multi-Sensor System |

| NAM-NEST | North American Mesoscale Nest |

| NCAR | National Center for Atmospheric Research |

| NHD | National Hydrography Dataset |

| NOAA | National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration |

| NSE | The Nash–Sutcliffe Model Efficiency Coefficient |

| NWM | National Water Model |

| NWP | Numerical Weather Prediction |

| OARC | Office of Water Prediction Analysis of Record for Calibration |

| PBIAS | Percent Bias |

| RAP | Rapid Refresh |

| RSR | Mean Square Error Observation Standard Deviation Ratio |

| USDM | United States Drought Monitor |

| WRF-Hydro | Water Research and Forecasting Hydrological Model |

References

- Choi, E.; Rigden, A.J.; Tangdamrongsub, N.; Jasinski, M.F.; Mueller, N.D. US crop yield losses from hydroclimatic hazards. Environ. Res. Lett. 2023, 19, 014005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupngam, T.; Messiga, A.J. Unraveling the Interactions between Flooding Dynamics and Agricultural Productivity in a Changing Climate. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Leng, G.; Peng, J. Recent Changes in the Occurrences and Damages of Floods and Droughts in the United States. Water 2018, 10, 1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuwayama, Y.; Thompson, A.; Bernknopf, R.; Zaitchik, B.; Vail, P. Estimating the impact of drought on agriculture using the US Drought Monitor. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2019, 101, 193–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodziewicz, D.; Dice, J. Drought Risk to the Agriculture Sector. Econ. Rev. 2020, 105, 61–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanir, T.; Yildirim, E.; Ferreira, C.M.; Demir, I. Social vulnerability and climate risk assessment for agricultural communities in the United States. Sci. Total. Environ. 2023, 908, 168346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabhaudhi, T.; Dirwai, T.L.; Taguta, C.; Sikka, A.; Lautze, J. Mapping Decision Support Tools (DSTs) on agricultural water productivity: A global systematic scoping review. Agric. Water Manag. 2023, 290, 108590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahsan, M.N.; Warner, J. The socioeconomic vulnerability index: A pragmatic approach for assessing climate change led risks–A case study in the south-western coastal Bangladesh. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2014, 8, 32–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey, D.; Garrido, A.; Calatrava, J. Comparison of different water supply risk management tools for irrigators: Option contracts and insurance. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2015, 65, 415–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collet, L.; Beevers, L.; Stewart, M.D. Decision-making and flood risk uncertainty: Statistical data set analysis for flood risk assessment. Water Resour. Res. 2018, 54, 7291–7308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodama, C.; Stevens, B.; Mauritsen, T.; Seiki, T.; Satoh, M. A new perspective for future precipitation change from intense extratropical cyclones. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2019, 46, 12435–12444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherrer, S.C.; Fischer, E.M.; Posselt, R.; Liniger, M.A.; Croci-Maspoli, M.; Knutti, R. Emerging trends in heavy precipitation and hot temperature extremes in Switzerland. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2016, 121, 2626–2637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, M.E.; Quinn, P.F.; Hewett, C.J. The Floods and Agriculture Risk Matrix: A decision support tool for effectively communicating flood risk from farmed landscapes. Int. J. River Basin Manag. 2013, 11, 237–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadul, E.; Masih, I.; De Fraiture, C. Adaptation strategies to cope with low, high and untimely floods: Lessons from the Gash spate irrigation system, Sudan. Agric. Water Manag. 2019, 217, 212–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.; Irmak, A.; Kabenge, I.; Irmak, S. Application of GIS and geographically weighted regression to evaluate the spatial non-stationarity relationships between precipitation vs. irrigated and rainfed maize and soybean yields. Trans. ASABE 2011, 54, 953–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corral-Quintana, S.; la Nuez, D.L.-D.; Verna, C.L.; Hernández, J.H.; de Lara, D.R.-M. How to improve strategic decision-making in complex systems when only qualitative information is available. Land Use Policy 2016, 50, 83–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarghami, M. Effective watershed management; Case study of Urmia Lake, Iran. Lake Reserv. Manag. 2011, 27, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azmi, M.; Rüdiger, C.; Walker, J.P. A data fusion-based drought index. Water Resour. Res. 2016, 52, 2222–2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murthy, C.; Laxman, B.; Sai, M.S. Geospatial analysis of agricultural drought vulnerability using a composite index based on exposure, sensitivity and adaptive capacity. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2015, 12, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Jiang, S.; Jin, J.; Ning, S.; Feng, P. Quantitative assessment of soybean drought loss sensitivity at different growth stages based on S-shaped damage curve. Agric. Water Manag. 2019, 213, 821–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehgal, V.K.; Dhakar, R. Geospatial approach for assessment of biophysical vulnerability to agricultural drought and its intra-seasonal variations. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2016, 188, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, W.; Fu, Q.; Liu, D.; Li, T.; Cheng, K.; Cui, S. A novel method for agricultural drought risk assessment. Water Resour. Manag. 2019, 33, 2033–2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheumann, W.; Freisem, C. The role of drainage for sustainable agriculture. J. Appl. Irrig. Sci. 2002, 37, 33–61. [Google Scholar]

- Ritzema, H. Drain for Gain: Managing salinity in irrigated lands—A review. Agric. Water Manag. 2016, 176, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, B.L., II; Kasperson, R.E.; Matson, P.A.; McCarthy, J.J.; Corell, R.W.; Christensen, L.; Eckley, N.; Kasperson, J.X.; Luers, A.; Martello, M.L.; et al. A framework for vulnerability analysis in sustainability science. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 8074–8079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, C.; Huo, Z. Optimizing irrigation and drainage by considering agricultural hydrological process in arid farmland with shallow groundwater. J. Hydrol. 2020, 585, 124785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Playán, E.; Mateos, L. Modernization and optimization of irrigation systems to increase water productivity. Agric. Water Manag. 2006, 80, 100–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, T.; Hanjra, M.A.; Khan, S.; Hafeez, M. Building a climate resilient farm: A risk based approach for understanding water, energy and emissions in irrigated agriculture. Agric. Syst. 2011, 104, 729–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dizaj, A.A.; Noory, H.; Ebrahimian, H. Effect of irrigation depth reduction, planting date and cropping pattern on water productivity in West Lake Urmia, Iran. Irrig. Drain. 2018, 68, 191–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bales, J.; Flowers, T. Featured Collection Introduction: National Water Model IV. J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 2022, 58, 767–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quansah, J.; Doria, R.; Fall, S. Evaluating the Performance of the National Water Model: A Spatiotemporal Analysis of Streamflow Forecasting. Water 2025, 17, 2950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NOAA. The National Water Model; OWP Office of Water Prediction: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. Available online: https://water.noaa.gov/about/nwm (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Jachens, E.; Hutcheson, H.; Thomas, M. Groundwater-Surface Water Exchange and Streamflow Prediction using the National Water Model in the Northern High Plains Aquifer region, USA. In National Water Center Innovators Program Summer Institute Report 2018; Columbia Engineering: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kopp, S.; Cline, D.; Miniat, C.; Lucero, C.; Rothlisberger, J.; Levinson, D.; Evett, S.; Brusberg, M.; Lowenfish, M.; Strobel, M.; et al. Perspectives on the National Water Model. AWRA Impact 2018, 20, 10–11. [Google Scholar]

- Shastry, A.; Egbert, R.; Aristizabal, F.; Luo, C.; Yu, C.; Praskievicz, S. Using steady-state backwater analysis to predict inundated area from National Water Model streamflow simulations. JAWRA J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 2019, 55, 940–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.M.; Munasinghe, D.; Eyelade, D.; Cohen, S. An integrated evaluation of the National Water Model (NWM)–Height Above Nearest Drainage (HAND) flood mapping methodology. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2019, 19, 2405–2420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viterbo, F.; Mahoney, K.; Read, L.; Salas, F.; Bates, B.; Elliott, J.; Cosgrove, B.; Dugger, A.; Gochis, D.; Cifelli, R. A multiscale, hydrometeorological forecast evaluation of National Water Model forecasts of the May 2018 Ellicott City, Maryland, flood. J. Hydrometeorol. 2020, 21, 475–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; D’Angelo, C.; Maidment, D.R.; Passalacqua, P. Application of a large-scale terrain-analysis-based flood mapping system to Hurricane Harvey. J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 2022, 58, 149–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Kumar, S. Predictability of seasonal streamflow and soil moisture in National Water Model and a humid Alabama-Coosa-Tallapoosa River Basin. J. Hydrometeorol. 2020, 21, 1447–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raczynski, K.; Dyer, J. Variability of annual and monthly streamflow droughts over the southeastern United States. Water 2022, 14, 3848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S.1643-117th Congress (2021–2022): Alabama Black Belt National Heritage Area Act (2021-05-13). Available online: https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/senate-bill/1643 (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Smith, E.A.; Johnson, L.C.; Langdon, D.W., Jr.; Aldrich, T.H.; Cunningham, K.M. Report on the Geology of the Coastal Plain of Alabama; Special Report 6; Brown Printing Company, State Printers: Monterey Park, CA, USA, 1894; p. 759. Available online: https://books.google.com/books?id=BzsxAQAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Stephenson, L.W.; Monrow, W.H. Stratigraphy of the Upper Cretaceous series in Mississippi and Alabama; Bulletin V. 22 12; American Association of Petroleum Geologists: Tulsa, OK, USA, 1938; pp. 1639. Available online: https://ngmdb.usgs.gov/Prodesc/proddesc_87938.htm (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Winemiller, T. Black Belt Region in Alabama. In Encyclopedia of Alabama; Alabama Humanities Alliance: Birmingham, AL, USA, 2009; Available online: https://encyclopediaofalabama.org/article/black-belt-region-in-alabama/ (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- USGS. Hydrologic Unit Codes (HUCs) Explained; USGS: Reston, VA, USA, 2024. Available online: https://nas.er.usgs.gov/about/hucs.aspx (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- USGS. USGS Current Water Data for the Nation. 2024. Available online: https://waterdata.usgs.gov/nwis/rt (accessed on 10 April 2024).

- NOAA. National Water Model. Available online: https://toolkit.climate.gov/tool/national-water-model (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Gochis, D.J.; Cosgrove, B.; Dugger, A.L.; Karsten, L.; Sampson, K.M.; McCreight, J.L.; Flowers, T.; Clark, E.P.; Vukicevic, T.; Salas, F.; et al. Multi-Variate Evaluation of the NOAA National Water Model; H33G-01; AGU Fall Meeting Abstracts; American Geophysical Union: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. Available online: https://ui.adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2018AGUFM.H33G..01G/abstract (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Cosgrove, B.; Gochis, D.; Flowers, T.; Dugger, A.; Ogden, F.; Graziano, T.; Clark, E.; Cabell, R.; Casiday, N.; Cui, Z.; et al. NOAA’s National Water Model: Advancing operational hydrology through continental-scale modeling. JAWRA J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 2024, 60, 247–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haslinger, K.; Koffler, D.; Schöner, W.; Laaha, G. Exploring the link between meteorological drought and streamflow: Effects of climate-catchment interaction. Water Resour. Res. 2014, 50, 2468–2487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Berríos, N.L.; Soto-Bayó, S.; Holupchinski, E.; Fain, S.J.; Gould, W.A. Correlating drought conservation practices and drought vulnerability in a tropical agricultural system. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2018, 33, 279–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Drought Mitigation Center. What is the US Drought Monitor. United States Drought Monitor. 2024. Available online: https://droughtmonitor.unl.edu/About/WhatistheUSDM.aspx (accessed on 18 May 2024).

- Auer, I.; Böhm, R. Combined temperature-precipitation variations in Austria during the instrumental period. Theor. Appl. Clim. 1994, 49, 161–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmielewski, F.-M.; Potts, J. The relationship between crop yields from an experiment in southern England and long-term climate variations. Agric. For. Meteorol. 1995, 73, 43–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, C.; Shiva, J.S.; McDonald, S.; Nabors, A. Assessing Retrospective National Water Model Streamflow with Respect to Droughts and Low Flows in the Colorado River Basin. JAWRA J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 2019, 55, 964–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kothari, K.; Ale, S.; Bordovsky, J.P.; Thorp, K.R.; Porter, D.O.; Munster, C.L. Simulation of efficient irrigation management strategies for grain sorghum production over different climate variability classes. Agric. Syst. 2019, 170, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lins, H.F.; Slack, J.R. Seasonal and Regional Characteristics of U.S. Streamflow Trends in the United States from 1940 to 1999. Phys. Geogr. 2005, 26, 489–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luce, C.H.; Holden, Z.A. Declining annual streamflow distributions in the Pacific Northwest United States, 1948–2006. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2009, 36, L16401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ames, D. Introduction to the National Water Model. Hydrolearn. 2020. Available online: https://apps.edx.hydrolearn.org/learning/course/course-v1:BYU+NWM101+2021/home (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- USDA. 2022 Census of Agriculture: Alabama, State and County Data (AC-22-A-1, p. 741). United States Department of Agriculture. 2024. Available online: https://www.nass.usda.gov/Publications/AgCensus/2022/Full_Report/Volume_1,_Chapter_1_State_Level/Alabama/alv1.pdf (accessed on 12 April 2024).

- Alabama Department of Agriculture and Industries. Alabama Agricultural Facts (p. 2). United States Department of Agriculture. 2022. Available online: https://www.nass.usda.gov/Statistics_by_State/Alabama/Publications/More_Features/ALAgFacts.pdf (accessed on 12 April 2024).

- National Agricultural Statistic Service (NASS). CropScape—NASS CDL Program. 2022. Available online: https://nassgeodata.gmu.edu/CropScape/ (accessed on 12 April 2024).

- USDA; NASS. Usual Planting and Harvesting Dates for U.S. Field Crops; Agricultural Handbook 628; United States Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 1997; p. 51. Available online: https://swat.tamu.edu/media/90113/crops-typicalplanting-harvestingdates-by-states.pdf (accessed on 12 April 2024).

- Boguszewska-Mańkowska, D.; Ruszczak, B.; Zarzyńska, K. Classification of potato varieties drought stress tolerance using supervised learning. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brackins, J.T.; Kalyanapu, A.J. Using ADCIRC and HEC-FIA Modeling to Predict Storm Surge Impact on Coastal Infrastructure. In Proceedings of the World Environmental and Water Resources Congress, West Palm Beach, FL, USA, 22–26 May 2016; pp. 203–212. [Google Scholar]

- García-León, D.; Contreras, S.; Hunink, J. Comparison of meteorological and satellite-based drought indices as yield predictors of Spanish cereals. Agric. Water Manag. 2019, 213, 388–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhtari, F.; Soltani, S.; Mousavi, S.A. Assessment of Flood Damage on Humans, Infrastructure, and Agriculture in the Ghamsar Watershed Using HEC-FIA Software. Nat. Hazards Rev. 2017, 18, 04017006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidek, L.M.; Yalit, M.R.; Djuladi, D.A.; Marufuzzaman, M. Flood Damage Assessment for Pergau Hydroelectric Power Project using HEC-FIA. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 704, 012002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todisco, F.; Vergni, L.; Mannocchi, F. Operative Approach to Agricultural Drought Risk Management. J. Irrig. Drain. Eng. 2009, 135, 654–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobin, A. Weather related risks in Belgian arable agriculture. Agric. Syst. 2018, 159, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valverde-Arias, O.; Garrido, A.; Valencia, J.L.; Tarquis, A.M. Using geographical information system to generate a drought risk map for rice cultivation: Case study in Babahoyo canton (Ecuador). Biosyst. Eng. 2018, 168, 26–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Jin, J.; Jiang, S.; Ning, S.; Cui, Y.; Zhou, Y. Simulated Assessment of Summer Maize Drought Loss Sensitivity in Huaibei Plain, China. Agronomy 2019, 9, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Tian, Z.; He, X.; Wang, J.; Sun, L.; Fischer, G.; Fan, D.; Zhong, H.; Wu, W.; Pope, E.; et al. Future increases in irrigation water requirement challenge the water-food nexus in the northeast farming region of China. Agric. Water Manag. 2019, 213, 594–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Streamflow (SF) Percentiles | B1 Score |

|---|---|---|

| Extreme Wetness | SF ≥ 90th | 8 |

| Severe Wetness | 80th ≥ SF < 90th | 4 |

| Moderate Wetness | 70th ≥ SF < 80th | 2 |

| Normal | 30th ≥ SF< 70th | −0.1 |

| Abnormally Dry | 20th ≥ SF < 30th | −1 |

| Moderate Drought | 10th ≥ SF < 20th | −2 |

| Severe Drought | 5th ≥ SF< 10th | −5 |

| Extreme Drought | 2nd ≥ SF < 5th | −8 |

| Exceptional Drought | SF < 2nd | −10 |

| Range | Class | Description |

|---|---|---|

| AWRI ≥ +7 | WE-3: Critical Water Excess | Widespread crop losses, movement of animals to the highland, and some damage to infrastructure |

| +4 ≤ AWRI < +7 | WE-2: Severe Water Excess | Likely crops will be lost to waterlogging |

| +2 ≤ AWRI < +4 | WE-1: Moderate Water Excess | crops, waterlogging issues, or a reduction in yield production |

| −2 < AWRI < +2 | WN-0: Normal | Normal crop development |

| −3 < AWRI ≤ −2 | WS-1: Abnormally Dry | Some yield reduction and longer duration to obtain maturity |

| −3.5 < AWRI ≤ −3 | WS-2: Moderate Water Scarcity | Some damage to crops |

| −6 < AWRI ≤ −3.5 | WS-3: Severe Water Scarcity | Crop and pasture losses likely |

| AWRI ≤ −6 | WS-4: Critical Water Scarcity | Major crop/pasture losses, and widespread water reduction |

| Farm | Reach ID | Stream Order | County | HUC −10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brown and Smith | 21687364 | 7 | Dallas | Soapstone Creek |

| BBMC Selma | 21662394 | 6 | Dallas | Lower Cahaba River |

| Blueberry and TU Organic Farm | 21717804 | 6 | Macon | Calebee Creek |

| Classes | Reach ID: 21717804 (cms) | Reach ID: 21687364 (cms) | Reach ID: 21662394 (cms) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exceptional Drought | Value ≤ 36 | Value ≤ 147 | Value ≤ 10 |

| Extreme Drought | 36 > Value ≤ 41 | 147 > Value ≤ 165 | 10 > Value ≤ 12 |

| Severe Drought | 41 > Value ≤ 46 | 165 > Value ≤ 184 | 12 > Value ≤ 14 |

| Moderate Drought | 46 > Value ≤ 55 | 184 > Value ≤ 223 | 14 > Value ≤ 19 |

| Abnormally Dry | 55 > Value ≤ 63 | 233 > Value ≤ 269 | 19 > Value ≤ 24 |

| Normal | 63 > Value ≤ 130 | 269 > Value ≤ 653 | 24 > Value ≤ 70 |

| Moderate Wetness | 130 > Value ≤ 184 | 653 > Value ≤ 866 | 70 > Value ≤ 100 |

| Severe Wetness | 184 > Value ≤ 287 | 866 > Value ≤ 1266 | 100 > Value ≤ 161 |

| Extreme Wetness | Value > 287 | Value > 1266 | Value > 161 |

| 8 May 2024 | Reach ID: 21717804 | Reach ID: 21687364 | Reach ID: 21662394 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Week 1 | Moderate wetness | Normal | Normal | Normal | Normal | Normal/Abnormally dry |

| Week 2 | Moderate wetness | Normal | Normal | |||

| Week 3 | Moderate wetness | Normal | Normal | |||

| Week 4 | Moderate wetness | Normal | Normal/Abnormally dry | |||

| Infrastructure | B1 | B2 | B3 | AWRI Score | Risk Class |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | +2.0 | +2.0 | 0.0 | +4.0 | WE-2 (Severe Water Excess) |

| With drainage | +2.0 | +2.0 | −2.0 | +2.0 | WE-1 (Moderate Water Excess) |

| Infrastructure | Risk Framing | B1 | B2 | B3 | AWRI Score | Risk Class |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | Excess | −0.1 | +1.5 | 0.0 | +1.4 | WN-0 (Normal) |

| With irrigation | Scarcity | −0.1 | −1.5 | +2.5 | +0.9 | WN-0 (Normal) |

| Period | Week1 | Week 2 | Week 3 | Week 4 | Resilience Measures | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crop | NS | NE | E | E | E | |

| Dry bean | −1.6 | 1.9 | 4 | 4 | 4 | No measure |

| 0.9 | −0.1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | Measures | |

| Green beans | −1.6 | 1.9 | 4 | 4 | 4 | No measure |

| 0.9 | −0.1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | Measures | |

| Watermelon | Out of season | 4 | 3.5 | 3.5 | No measure | |

| 2 | 1.5 | 1.5 | Measures | |||

| Sunflower | Out of season | 4 | 4 | 3.5 | No measure | |

| 2 | 2 | 1.5 | Measures | |||

| Peanut | −1.6 | 1.9 | 4 | 4 | 4 | No measure |

| 0.9 | −0.1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | Measures | |

| Spring wheat | −1.6 | 1.4 | 3.5 | 3.5 | 3.5 | No measure |

| 0.9 | −0.6 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | Measures | |

| Winter wheat | −1.6 | 1.4 | 3.5 | 3.5 | 3.5 | No measure |

| 0.9 | −0.6 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | Measures | |

| Corn | −2.1 | 1.4 | 3.5 | 3.5 | 3.5 | No measure |

| 0.4 | −0.6 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | Measures | |

| Soybean | −1.6 | 1.9 | 3.5 | 3.5 | 3.5 | No measure |

| 0.9 | −0.1 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | Measures | |

| Cotton | −1.6 | 1.9 | 4 | 4 | 4 | No measure |

| 0.9 | −0.1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | Measures | |

| Sorghum | −1.6 | 1.4 | 3.5 | 3.5 | 3.5 | No measure |

| 0.9 | −0.6 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | Measures | |

| Period | Week1 | Week 2 | Week 3 | Week 4 | Resilience Measures | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crop | NS | NE | NS | NE | NS | NE | NS | NE | |

| Dry bean | −1.6 | 1.9 | −1.6 | 1.9 | −1.6 | 1.9 | −1.6 | 1.9 | No measure |

| 0.9 | −0.1 | 0.9 | −0.1 | 0.9 | −0.1 | 0.9 | −0.1 | Measures | |

| Green beans | −1.6 | 1.9 | −1.6 | 1.9 | −1.6 | 1.9 | −1.6 | 1.9 | No measure |

| 0.9 | −0.1 | 0.9 | −0.1 | 0.9 | −0.1 | 0.9 | −0.1 | Measures | |

| Watermelon | Out of season | −2.1 | 1.9 | −2.1 | 1.4 | −2.1 | 1.4 | No measure | |

| Out of season | 0.4 | −0.1 | 0.4 | −0.6 | 0.4 | −0.6 | Measures | ||

| Sunflower | Out of season | −1.6 | 1.9 | −1.6 | 1.9 | −1.6 | 1.4 | No measure | |

| Out of season | 0.9 | −0.1 | 0.9 | −0.1 | 0.9 | −0.6 | Measures | ||

| Peanut | −1.6 | 1.9 | −1.6 | 1.9 | −1.6 | 1.9 | −2.1 | 1.9 | No measure |

| 0.9 | −0.1 | 0.9 | −0.1 | 0.9 | −0.1 | 0.4 | −0.1 | Measures | |

| Spring wheat | −1.6 | 1.4 | −2.1 | 1.4 | −2.1 | 1.4 | −2.1 | 1.4 | No measure |

| 0.9 | −0.6 | 0.4 | −0.6 | 0.4 | −0.6 | 0.4 | −0.6 | Measures | |

| Winter wheat | −1.6 | 1.4 | −1.6 | 1.4 | −1.6 | 1.9 | −2.1 | 1.4 | No measure |

| 0.9 | −0.6 | 0.9 | −0.6 | 0.9 | −0.1 | 0.4 | −0.6 | Measures | |

| Corn | −2.1 | 1.4 | −2.1 | 1.4 | −2.1 | 1.4 | −2.1 | 1.4 | No measure |

| 0.4 | −0.6 | 0.4 | −0.6 | 0.4 | −0.6 | 0.4 | −0.6 | Measures | |

| Soybean | −1.6 | 1.9 | −1.6 | 1.4 | −1.6 | 1.4 | −1.6 | 1.4 | No measure |

| 0.9 | −0.1 | 0.9 | −0.6 | 0.9 | −0.6 | 0.9 | −0.6 | Measures | |

| Cotton | −1.6 | 1.9 | −1.6 | 1.9 | −1.6 | 1.9 | −2.1 | 1.9 | No measure |

| 0.9 | −0.1 | 0.9 | −0.1 | 0.9 | −0.1 | 0.4 | −0.1 | Measures | |

| Sorghum | −1.6 | 1.4 | −1.6 | 1.4 | −1.6 | 1.4 | −1.6 | 1.4 | No measure |

| 0.9 | −0.6 | 0.4 | −0.6 | 0.4 | −0.6 | 0.4 | −0.6 | Measures | |

| Period | Week1 | Week 2 | Week 3 | Week 4 | Resilience Measures | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crop | S | NS | NE | NS | NE | S | |

| Dry bean | −2.5 | −1.6 | 1.9 | −1.6 | 1.9 | −2.5 | No measure |

| 0 | 0.9 | −0.1 | 0.9 | −0.1 | 0 | Measures | |

| Green beans | −2.5 | −1.6 | 1.9 | −1.6 | 1.9 | −2.5 | No measure |

| 0 | 0.9 | −0.1 | 0.9 | −0.1 | 0 | Measures | |

| Watermelon | Out of season | −2.1 | 1.9 | −2.1 | 1.4 | −3 | No measure |

| 0.4 | −0.1 | 0.4 | −0.6 | −0.5 | Measures | ||

| Sunflower | Out of season | −1.6 | 1.9 | −1.6 | 1.9 | −2.5 | No measure |

| 0.9 | −0.1 | 0.9 | −0.1 | 0 | Measures | ||

| Peanut | −2.5 | −1.6 | 1.9 | −1.6 | 1.9 | −3 | No measure |

| 0 | 0.9 | −0.1 | 0.9 | −0.1 | −0.5 | Measures | |

| Spring wheat | −2.5 | −2.1 | 1.4 | −2.1 | 1.4 | −3 | No measure |

| 0 | 0.4 | −0.6 | 0.4 | −0.6 | −0.5 | Measures | |

| Winter wheat | −2.5 | −1.6 | 1.4 | −1.6 | 1.9 | −3 | No measure |

| 0 | 0.9 | −0.6 | 0.9 | −0.1 | −0.5 | Measures | |

| Corn | −3 | −2.1 | 1.4 | −2.1 | 1.4 | −3 | No measure |

| −0.5 | 0.4 | −0.6 | 0.4 | −0.6 | −0.5 | Measures | |

| Soybean | −2.5 | −1.6 | 1.4 | −1.6 | 1.4 | −2.5 | No measure |

| 0 | 0.9 | −0.6 | 0.9 | −0.6 | 0 | Measures | |

| Cotton | −2.5 | −1.6 | 1.9 | −1.6 | 1.9 | −3 | No measure |

| 0 | 0.9 | −0.1 | 0.9 | −0.1 | −0.5 | Measures | |

| Sorghum | −2.5 | −1.6 | 1.4 | −2.6 | 1.4 | −2.5 | No measure |

| 0 | 0.4 | −0.6 | 0.4 | −0.6 | −0.5 | Measures | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Quansah, J.E.; Doria, R.G.; Olakanmi, E.E.; Fall, S. Development of an Agricultural Water Risk Indicator Framework Using National Water Model Streamflow Forecasts. Hydrology 2026, 13, 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrology13020043

Quansah JE, Doria RG, Olakanmi EE, Fall S. Development of an Agricultural Water Risk Indicator Framework Using National Water Model Streamflow Forecasts. Hydrology. 2026; 13(2):43. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrology13020043

Chicago/Turabian StyleQuansah, Joseph E., Ruben G. Doria, Eniola E. Olakanmi, and Souleymane Fall. 2026. "Development of an Agricultural Water Risk Indicator Framework Using National Water Model Streamflow Forecasts" Hydrology 13, no. 2: 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrology13020043

APA StyleQuansah, J. E., Doria, R. G., Olakanmi, E. E., & Fall, S. (2026). Development of an Agricultural Water Risk Indicator Framework Using National Water Model Streamflow Forecasts. Hydrology, 13(2), 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrology13020043