Flash floods are among the most destructive hydro-meteorological hazards in northeastern Bangladesh, particularly in the Surma River catchment of Sylhet. The region’s proximity to the Meghalaya foothills exposes it to intense, short-duration rainfall events, which generate rapid inflows into the low-lying haor wetlands. These floods develop suddenly, causing abrupt rises in water levels and leading to extensive inundation that damages agriculture, settlements, transport networks, and urban infrastructure [

1,

2,

3]. The catastrophic 2022 flash floods in Sylhet underscored the vulnerability of the region and revealed critical shortcomings in flood forecasting and warning systems [

4] which often rely on sparse hydrological data, one-dimensional (1D) routing models, and inadequate spatial representation of inundation. Several local studies have attempted to analyze flash floods and river flooding in northeastern Bangladesh, including flash flood forecasting of the Manu River system in the northeast region [

2,

5,

6]. Decision support tools based on statistics or an artificial neural network (ANN) show improve forecasted boundary conditions [

6]. During 2008, flood forecasting was carried out for four cross-border catchments: the Jadukata river, the Khowai river, the Manu river, and the Barak river catchments using MIKE11 and SWAT. Performance of the model developed based on MIKE 11 is better and it was found that the basin lag time is shorter than a day [

5]. A flash flood forecasted in the northeast region of Bangladesh with the lead time of 2 days has been developed using the MIKE 11 and MIKE BASIN software, but the forecasted flood data were not sufficient [

7]. Flash floods have been modeled both hydrologically and hydraulically around the world [

3,

8,

9]. Apart from this national activity, few latest research on flash floods around Bangladesh have considered hydrological models viz. application of the HEC-HMS to simulate rainfall–runoff response in the Haor basin [

10], while Akter [

11] examined rainfall variability in the Surma–Kushiyara system and flood risk in the Feni–Muhuri–Selonia river basin [

12]. However, BWDB [

13] reported on the limitations of operational forecasting during the 2022 Sylhet floods. Recently, the hydrological modeling of the flash flood in Sylhet was carried out using the HEC-HMS [

1] and found better performance to feature the event-based flood rather than continuous flood modeling due to the lack of data. To overcome observed data scarcity, remote sensing and GIS-based techniques are often performed to assess inundation risk in flood-prone areas [

12,

14,

15,

16]. These efforts have advanced understanding of regional hydrology but remain constrained by reliance on lumped or semi-distributed models, limited validation datasets, and insufficient capacity to represent spatial inundation dynamics. Studies around the world demonstrate that two-dimensional (2D) hydrodynamic models, viz. Delft3D and its flexible mesh (FM) version, can simulate flooding processes with high spatial fidelity [

3,

8,

9,

17,

18]. In Bangladesh, applications of Delft3D FM have been concentrated on coastal flooding, tidal dynamics, and storm surges [

19,

20,

21,

22] with little extension to inland flash flood contexts. Moreover, local studies have rarely integrated hydrodynamic simulations with spatial validation using remote sensing, despite the growing availability of Sentinel-1 SAR flood maps.

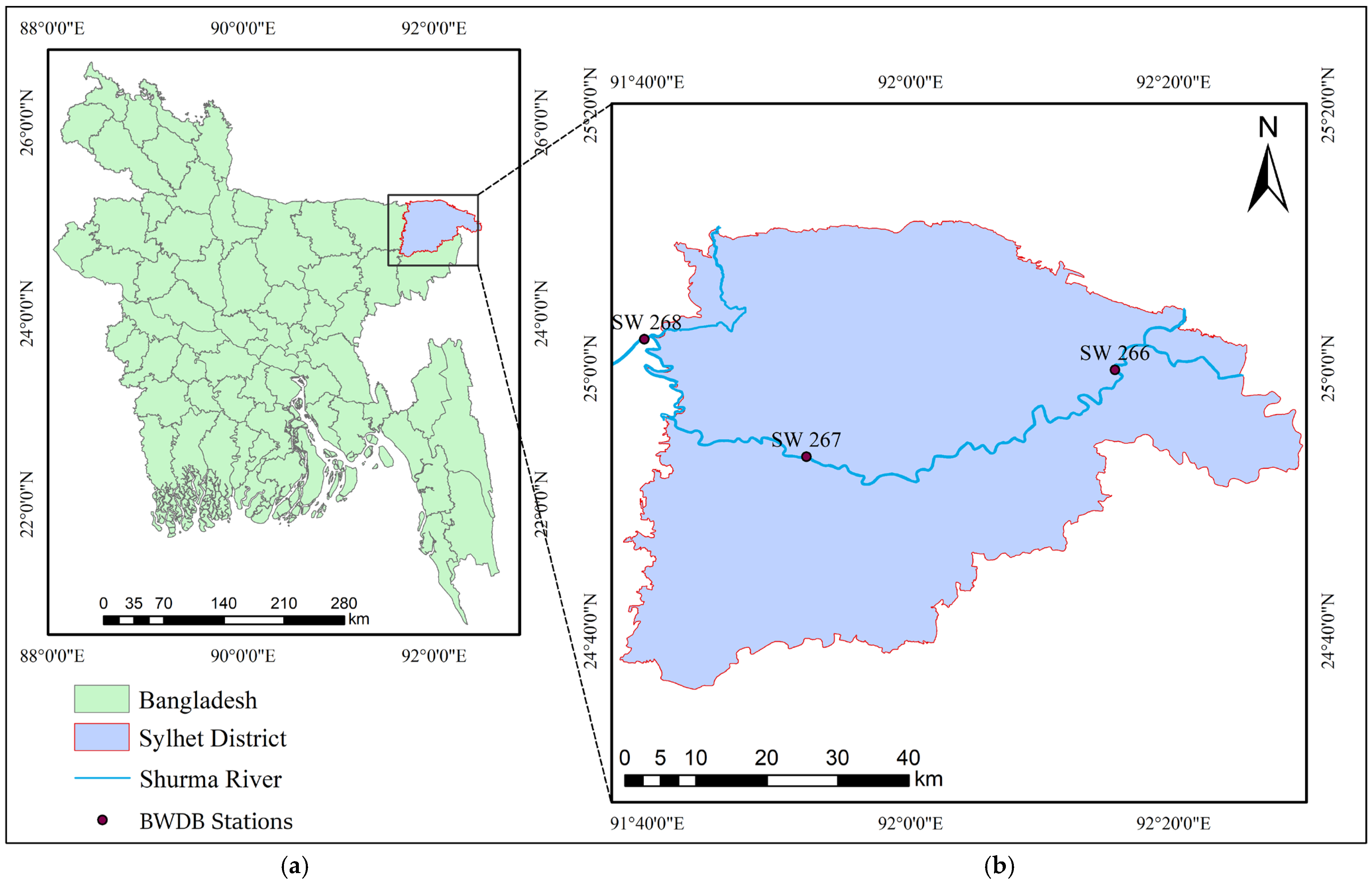

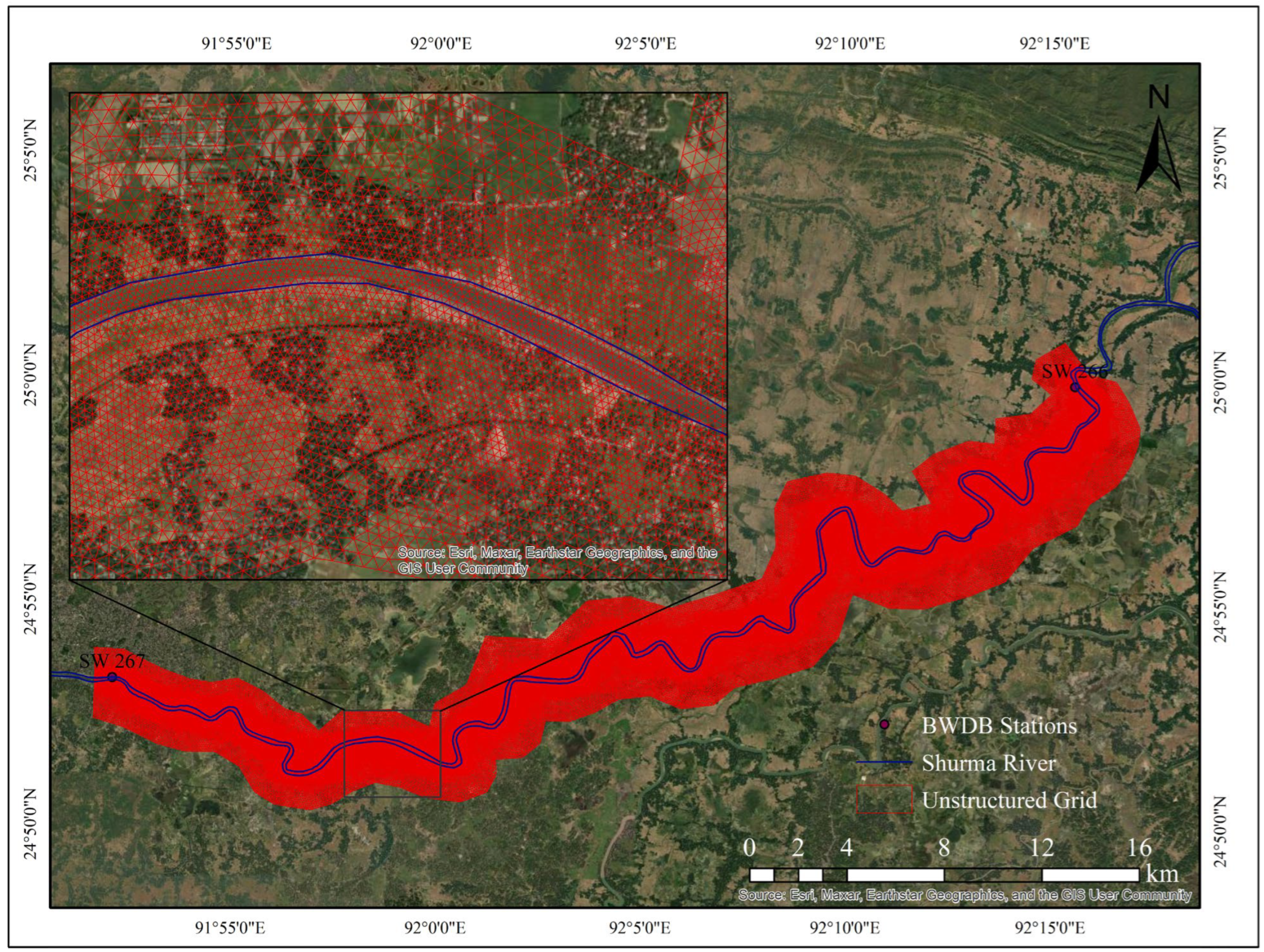

This study addresses these gaps by applying Delft3D FM Suite to simulate flash flood inundation in the Surma River catchment of Sylhet district. Specifically, the model is calibrated with hydrological data, validated against Sentinel-1A satellite-derived flood maps, and used to assess inundation extent and depth during major flood events. To the best of our knowledge, no prior published work has applied Delft3D FM for inland flash flood simulation in the Sylhet region. Previous studies have primarily employed one-dimensional (1D) or semi-distributed hydrological models such as MIKE11 [

7,

13] and HEC-HMS [

1]. Therefore, this study represents one of the first applications of the Delft3D Flexible Mesh hydrodynamic model for event-based inland flash flood modeling in northeastern Bangladesh.

The novelty lies in integrating a flexible mesh 2D hydrodynamic model with radar-based remote sensing validation, providing a spatially explicit approach that has not previously been used in Bangladesh for flash flood contexts. By bridging hydrograph-based studies with high-resolution inundation modeling, this research advances methodological practice and offers practical insights for flood risk assessment, early warning, and climate-resilient urban planning in one of the most vulnerable flash flood-prone regions of Bangladesh.