Revealing Emerging Hydroclimatic Shifts: Advanced Trend Analysis of Rainfall and Streamflow in the Navasota River Watershed

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Navasota River Watershed

2.2. Dataset

2.2.1. Precipitation Data

2.2.2. Streamflow Data

2.2.3. Land Cover Data

2.3. Data Analysis

2.3.1. Performance of PRISM Data

2.3.2. Spatiotemporal Precipitation Changes Before and After Dam Construction

2.3.3. Autocorrelation Analysis

2.3.4. Standard Mann–Kendall and Modified Mann–Kendall Trend Tests

2.3.5. Change Point Detection

3. Results

3.1. Performance of PRISM Data

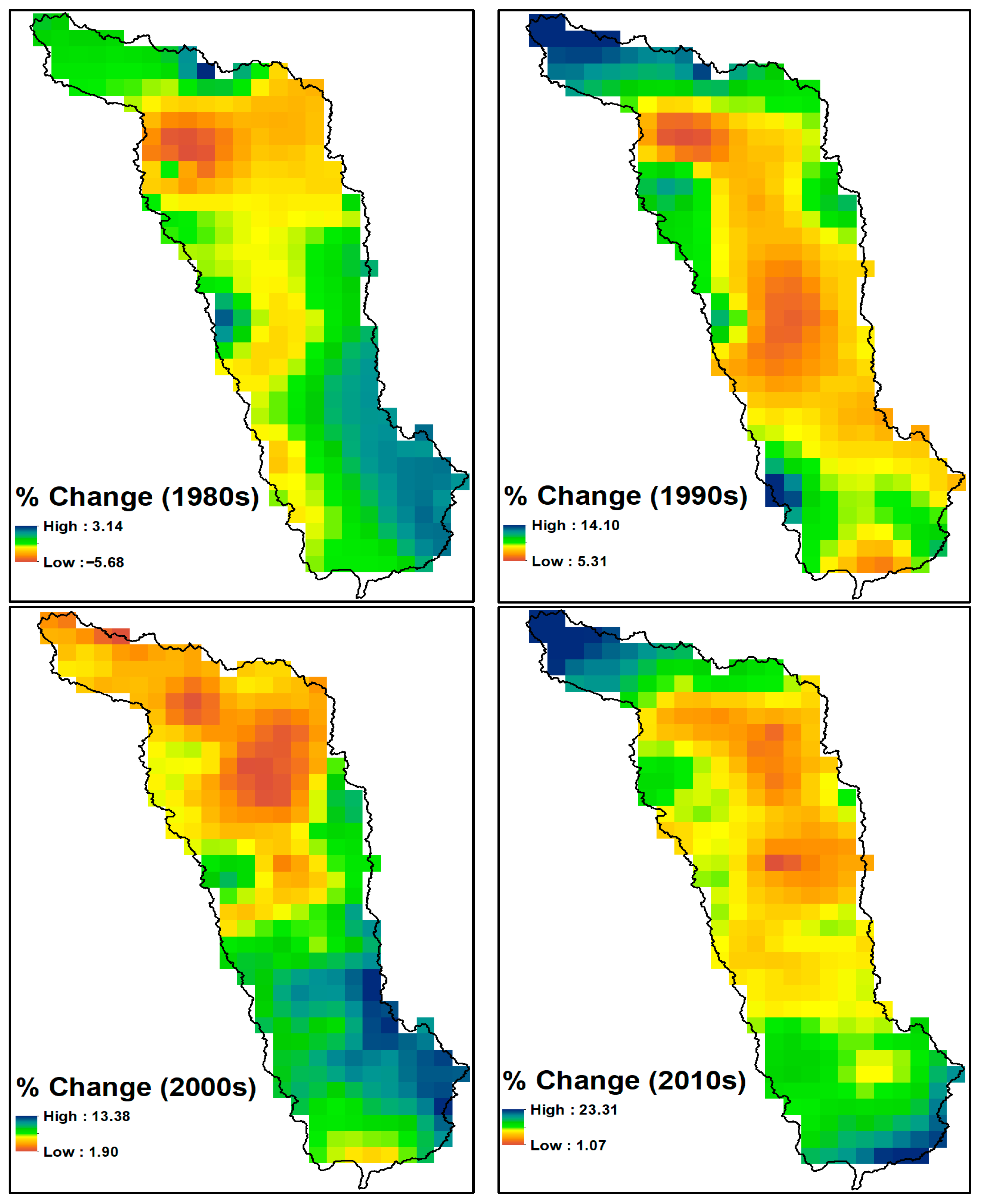

3.2. Spatiotemporal Precipitation Changes

3.3. Autocorrelation of Streamflow

3.4. Precipitation Trend

3.5. Streamflow Trend

3.6. Streamflow Change-Point Detection

4. Discussions

4.1. Spatiotemporal Changes in Precipitation and Implications for Flooding

4.2. Precipitation Trends and Seasonal Flood Risk

4.3. Streamflow Trends and Flooding Dynamics

4.4. Change-Point Detection and Hydrologic Regime Shifts

4.5. Implications of Autocorrelation Patterns on Flood Risk

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahmadiani, M.; Ferreira, S. Well-being effects of extreme weather events in the United States. Resour. Energy Econ. 2021, 64, 101213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, J.; Elliott, J.R. Natural disasters and local demographic change in the United States. Popul. Environ. 2013, 34, 293–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, K.; Peterson, M.; Marano, H. Extreme Weather, Extreme Costs: The Rising Financial Toll of Climate Change in the United States. Available online: https://www.americanprogress.org/article/extreme-weather-extreme-costs/ (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- NOAA-NCEI. 2017 U.S. Billion-Dollar Weather and Climate Disasters: A Historic Year in Context. Available online: https://www.climate.gov/disasters-2017 (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Montz, B.E.; Gruntfest, E. Flash flood mitigation: Recommendations for research and applications. Glob. Environ. Change Part B Environ. Hazards 2002, 4, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statkewicz, M.D.; Talbot, R.; Rappenglueck, B. Changes in precipitation patterns in Houston, Texas. Environ. Adv. 2021, 5, 100073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellsworth, C.E. The Floods in Central Texas in September, 1921; U.S. Geological Survey; Goyernment Printing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 1923.

- NCTCOG. North Central Texas floods: May–June 2015; North Central Texas Council of Governments: Tarrant, TX, USA, 2016; pp. 1–25.

- Lewis, J. Navasota River Flooding Caused by Rainfall, Water Release from Lake Limestone. Available online: https://www.kbtx.com/2024/05/08/navasota-river-flooding-caused-by-rainfall-water-release-lake-limestone/ (accessed on 18 May 2024).

- Rhodes, E.C.; Talchabhadel, R.; Jordan, T. A changing river: Long-term changes of sinuosity and land cover in the Navasota River Watershed, Texas. River 2024, 3, 152–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TWRI. Navasota River Flood Project Final Report; Texas Water Resources Institute: College Station, TX, USA, 2023.

- TWDB. Volumetric and Sedimentation Survey of Lake Limestone: March–April 2012 Survey; TWDB: Austin, TX, USA, 2014; pp. 1–32.

- Mishra, A.K.; Singh, V.P.; Özger, M. Seasonal streamflow extremes in Texas river basins: Uncertainty, trends, and teleconnections. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2011, 116, D08108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, E.D.; Venkataraman, K.; Chraibi, V.; Kannan, N. Hydrologic Trends in the Upper Nueces River Basin of Texas—Implications for Water Resource Management and Ecological Health. Hydrology 2019, 6, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamed, K.H. Trend detection in hydrologic data: The Mann–Kendall trend test under the scaling hypothesis. J. Hydrol. 2008, 349, 350–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryberg, K.R.; Hodgkins, G.A.; Dudley, R.W. Change points in annual peak streamflows: Method comparisons and historical change points in the United States. J. Hydrol. 2020, 583, 124307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najibi, N.; Devineni, N. Recent trends in the frequency and duration of global floods. Earth Syst. Dynam. 2018, 9, 757–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, J.D. Geomorphic Context, Constraints, and Change in the Lower Brazos and Navasota Rivers, Texas; Texas Water Development Board: Austin, TX, USA, 2006.

- Gregory, L.; Lazar, K.; Gitter, A. Navasota River Below Lake Limestone Watershed Protection Plan; Texas Water Resources Institute: College Station, TX, USA, 2017; p. 69.

- Marie, M.; Yirga, F.; Haile, M.; Ehteshammajd, S.; Azadi, H.; Scheffran, J. Time-series trend analysis and farmer perceptions of rainfall and temperature in northwestern Ethiopia. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 12904–12924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homer, C.; Dewitz, J.; Jin, S.; Xian, G.; Costello, C.; Danielson, P.; Gass, L.; Funk, M.; Wickham, J.; Stehman, S.; et al. Conterminous United States land cover change patterns 2001–2016 from the 2016 National Land Cover Database. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2020, 162, 184–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.; Homer, C.; Yang, L.; Danielson, P.; Dewitz, J.; Li, C.; Zhu, Z.; Xian, G.; Howard, D. Overall Methodology Design for the United States National Land Cover Database 2016 Products. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 2971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Jin, S.; Danielson, P.; Homer, C.; Gass, L.; Bender, S.M.; Case, A.; Costello, C.; Dewitz, J.; Fry, J.; et al. A new generation of the United States National Land Cover Database: Requirements, research priorities, design, and implementation strategies. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2018, 146, 108–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, J.; Stehman, S.V.; Sorenson, D.G.; Gass, L.; Dewitz, J.A. Thematic accuracy assessment of the NLCD 2019 land cover for the conterminous United States. GISci. Remote Sens. 2023, 60, 2181143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santhi, C.; Arnold, J.G.; Williams, J.R.; Dugas, W.A.; Srinivasan, R.; Hauck, L.M. Validation of the SWAT Model on a Large Rwer Basin with Point and Nonpoint Sources. JAWRA J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 2001, 37, 1169–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhaila, J.; Deni, S.M.; Zin, W.Z.W.; Jemain, A.A. Trends in peninsular Malaysia rainfall data during the southwest monsoon and northeast monsoon seasons: 1975–2004. Sains Malays. 2010, 39, 533–542. [Google Scholar]

- Hamed, K.H.; Ramachandra Rao, A. A modified Mann-Kendall trend test for autocorrelated data. J. Hydrol. 1998, 204, 182–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulaiman, N.H.; Kamarudin, M.K.A.; Mustafa, A.D.; Amran, M.A.; Azaman, F.; Abidin, I.Z.; Hairoma, N. Trend analysis of Pahang river using non-parametric analysis: Mann Kendall’s trend test. Malays. J. Anal. Sci. 2015, 19, 1327–1334. [Google Scholar]

- Kendall, M.G. Rank correlation methods. Br. J. Stat. Psychol. 1948, 9, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, H.B. Nonparametric tests against trend. Econometrica 1945, 13, 245–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendall, M.G.; Stuart, A. The Advanced Theory of Statistics; Hafner Publishing Company: Maple Grove, MN, USA, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Kendall, M.G. A New Measure of Rank Correlation. Biometrika 1938, 30, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendall, M.G. Rank Correlation Methods, 5th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Hipel, K.W.; McLeod, A.I. Time Series Modelling of Water Resources and Environmental Systems; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1994; Volume 45. [Google Scholar]

- Yue, S.; Wang, C. The Mann-Kendall Test Modified by Effective Sample Size to Detect Trend in Serially Correlated Hydrological Series. Water Resour. Manag. 2004, 18, 201–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettitt, A.N. A Non-Parametric Approach to the Change-Point Problem. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. C (Appl. Stat.) 1979, 28, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fooladi, M.; Golmohammadi, M.H.; Safavi, H.R.; Mirghafari, R.; Akbari, H. Trend analysis of hydrological and water quality variables to detect anthropogenic effects and climate variability on a river basin scale: A case study of Iran. J. Hydro-Environ. Res. 2021, 34, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, R.L.; Sishodia, R.P.; Tefera, G.W. Evaluation of Gridded Precipitation Data for Hydrologic Modeling in North-Central Texas. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 3860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, X.; Smith, P.K.; Li, J.; Li, B. Hydrological evaluation of gridded climate datasets in a texas urban watershed using soil and water assessment tool and artificial neural network. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 905774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboutalebi, M.; Torres-Rua, A.F.; Allen, N. Spatial and Temporal Analysis of Precipitation and Effective Rainfall Using Gauge Observations, Satellite, and Gridded Climate Data for Agricultural Water Management in the Upper Colorado River Basin. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 2058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Kumar, A. Winter 2015/16 Atmospheric and Precipitation Anomalies over North America: El Niño Response and the Role of Noise. Mon. Weather. Rev. 2018, 146, 909–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Qian, X.; Han, B.-P.; Luo, L.-C.; Hamilton, D.P. Effects of local climate and hydrological conditions on the thermal regime of a reservoir at Tropic of Cancer, in southern China. Water Res. 2012, 46, 2591–2604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murgulet, D.; Valeriu, M.; Hay, R.R.; Tissot, P.; Mestas-Nuñez, A.M. Relationships between sea surface temperature anomalies in the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans and South Texas precipitation and streamflow variability. J. Hydrol. 2017, 550, 726–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman Abdullahi, M.; Li, Y. Flood Risk Assessment, Future Trend Modeling, and Risk Communication: A Review of Ongoing Research. Nat. Hazards Rev. 2018, 19, 04018011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Zhang, R.; Wang, B. Scenario-based approach for emergency operational response: Implications for reservoir management decisions. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2022, 80, 103192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgakakos, A.P.; Yao, H.; Kistenmacher, M.; Georgakakos, K.P.; Graham, N.E.; Cheng, F.Y.; Spencer, C.; Shamir, E. Value of adaptive water resources management in Northern California under climatic variability and change: Reservoir management. J. Hydrol. 2012, 412–413, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Y.; Wang, H.; Jiang, C.; Ling, S. Seasonal Inflow Forecasts Using Gridded Precipitation and Soil Moisture Information: Implications for Reservoir Operation. Water Resour. Manag. 2019, 33, 3743–3757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brody, S.; Blessing, R.; Ross, A.; Fares, A.; Awal, R.; Murphy, R.R.; Juan, A.; Talchabhadel, R.; Rhodes, E.C.; Adams, J. Navasota River Flooding Project Report: Findings & Recommendations; Prairie View A&M University: Prairie View, TX, USA, 2022; pp. 1–51. [Google Scholar]

- Fiener, P.; Auerswald, K.; Van Oost, K. Spatio-temporal patterns in land use and management affecting surface runoff response of agricultural catchments—A review. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2011, 106, 92–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| ID | Station Name | Duration |

|---|---|---|

| TX-08110325 | Navasota River above Groesbeck | 1 June 1978–7 December 2021 |

| TX-08110325 | Navasota River near Groesbeck | 1 March 1965–30 April 1979 |

| TX-08110500 | Navasota River near Easterly | 27 March 1924–7 December 2021 |

| TX-08110800 | Navasota River near Bryan | 1 October 1996–7 December 2021 |

| Month | p-Value | Kendall’s Tau |

|---|---|---|

| January | 0.095 | 0.102 |

| February | 0.83 | −0.012 |

| March | 0.230 | 0.07 |

| April | 0.04 | −0.12 * |

| May | 0.067 | 0.025 |

| June | 0.033 | 0.13 ** |

| July | 0.39 | −0.05 |

| August | 0.74 | 0.02 |

| September | 0.23 | 0.07 |

| October | 0.15 | 0.08 |

| November | 0.45 | 0.04 |

| December | 0.46 | −0.04 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Fares, A.; Awal, R.; Adem, A.A.; Veettil, A.V.; Ouarda, T.B.M.J.; Brody, S.; Temimi, M. Revealing Emerging Hydroclimatic Shifts: Advanced Trend Analysis of Rainfall and Streamflow in the Navasota River Watershed. Hydrology 2026, 13, 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrology13010012

Fares A, Awal R, Adem AA, Veettil AV, Ouarda TBMJ, Brody S, Temimi M. Revealing Emerging Hydroclimatic Shifts: Advanced Trend Analysis of Rainfall and Streamflow in the Navasota River Watershed. Hydrology. 2026; 13(1):12. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrology13010012

Chicago/Turabian StyleFares, Ali, Ripendra Awal, Anwar Assefa Adem, Anoop Valiya Veettil, Taha B. M. J. Ouarda, Samuel Brody, and Marouane Temimi. 2026. "Revealing Emerging Hydroclimatic Shifts: Advanced Trend Analysis of Rainfall and Streamflow in the Navasota River Watershed" Hydrology 13, no. 1: 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrology13010012

APA StyleFares, A., Awal, R., Adem, A. A., Veettil, A. V., Ouarda, T. B. M. J., Brody, S., & Temimi, M. (2026). Revealing Emerging Hydroclimatic Shifts: Advanced Trend Analysis of Rainfall and Streamflow in the Navasota River Watershed. Hydrology, 13(1), 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrology13010012