Public Perceptions of Algorithmic Bias and Fairness in Cloud-Based Decision Systems

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

2.1. Algorithmic Bias in Information Systems

2.2. Bias in AI-Driven Hiring Systems

2.3. Bias in Healthcare Algorithms

2.4. Mitigating Bias in Recruitment

2.5. Fairness Metrics and Bias Mitigation Techniques

2.6. Additional Foundational Literature

3. Methods

3.1. Recruitment and Eligibility

3.2. Ethical Approval and Consent

3.3. Instrument

3.4. Reliability and Validity

3.5. Missing Data and Exclusions

3.6. Sample Characteristics

3.7. Survey Domains

- Awareness and knowledge of algorithmic bias (Q6–Q10);

- Perceptions of bias impact and fairness (Q11–Q15);

- Attitudes toward solutions, responsibility, and regulation (Q16–Q20);

- Trust in technology and fairness expectations (Q21–Q23);

- Prioritization of fairness in technology (Q24–Q25).

3.8. Procedure

3.9. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Overview of Result Presentation

4.2. Awareness and Understanding of Algorithmic Bias

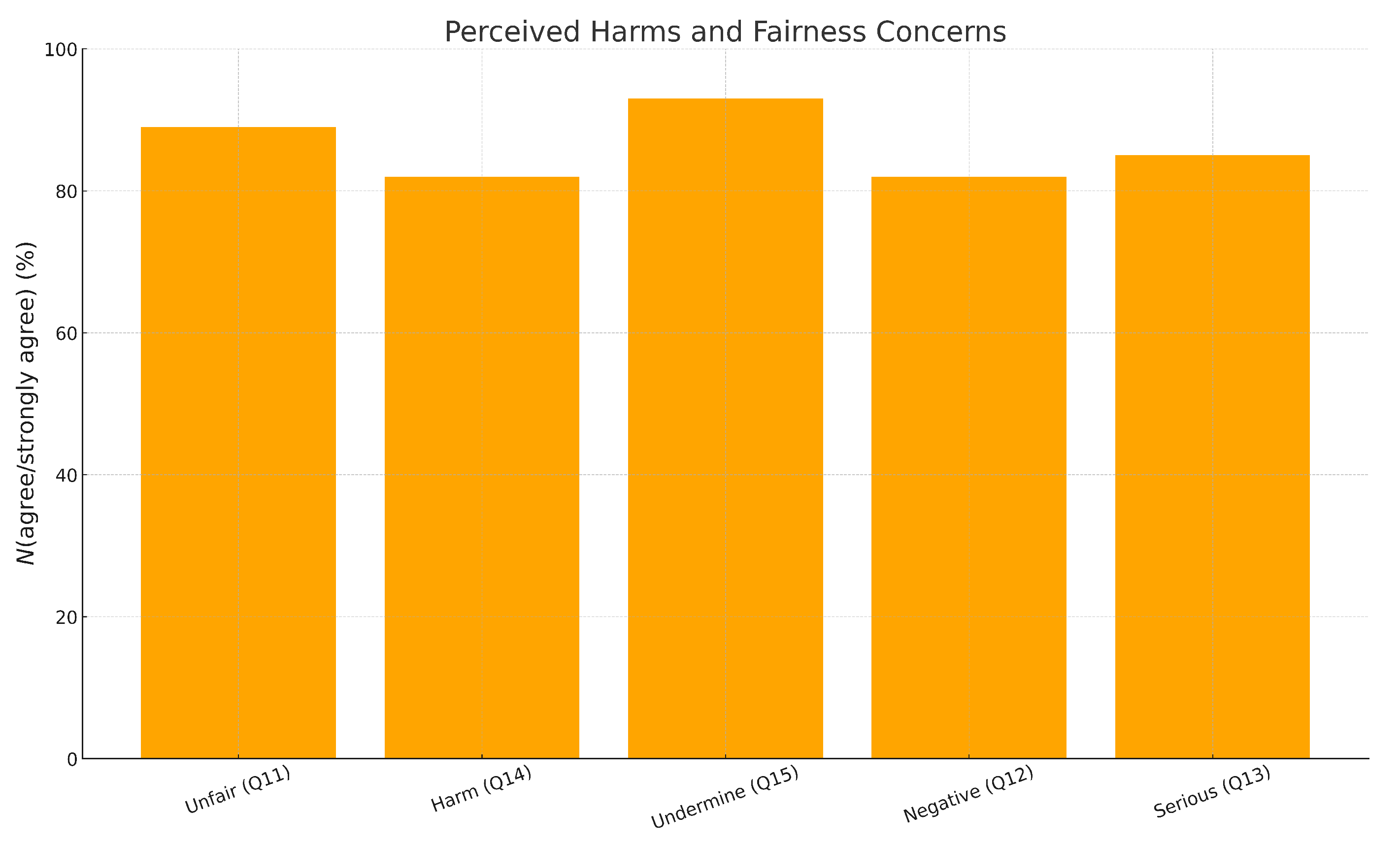

4.3. Perceived Harms and Fairness Concerns

4.4. Support for Solutions, Regulation, and Accountability

4.5. Trust in Technology and Fairness Expectations

4.6. Perceived Harms and Fairness Concerns

4.7. Support for Solutions, Regulation, and Accountability

4.8. Trust in Technology and Fairness Expectations

5. Discussion

Integration with Cloud-Based Data Query Systems

6. Recommendations

6.1. Education and Awareness

- Expand public-facing algorithmic literacy initiatives.

- Integrate fairness and ethics modules into computer science, data science, public policy, and engineering curricula.

- Provide practitioner training on bias measurement, mitigation, and governance standards.

6.2. Transparency and Communication

- Encouraging organizations to publicly disclose algorithmic audit results.

- Using communication strategies that make fairness metrics understandable to non-expert audiences.

6.3. Regulation and Policy

- Enforce regular audits of high-stakes algorithms.

- Establish independent oversight bodies for algorithmic accountability.

- Require lifecycle fairness assessments as part of cloud compliance regimes.

6.4. Technical Measures

6.5. Developer and Organizational Responsibility

- Elevate fairness as a key performance metric on par with accuracy and latency.

- Build cross-functional teams including ethicists, domain experts, and affected stakeholders.

- Maintain documentation and audit trails to support traceability and incident responses.

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Breck, E.; Polyzotis, N.; Roy, S.; Whang, S.E.; Zinkevich, M. Data Validation for Machine Learning. 2019. Available online: https://mlsys.org/Conferences/2019/doc/2019/167.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Breck, E.; Cai, S.; Nielsen, E.; Salib, M.; Sculley, D. The ML Test Score: A Rubric for ML Production Readiness. In Proceedings of the Machine Learning Systems Workshop at NIPS, Boston, MA, USA, 11–14 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Barocas, S.; Hardt, M.; Narayanan, A. Fairness and Machine Learning: Limitations and Opportunities; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Mehrabi, N.; Morstatter, F.; Saxena, N.; Lerman, K.; Galstyan, A. A Survey on Bias and Fairness in Machine Learning. ACM Comput. Surv. 2021, 54, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddique, S.M.; Tipton, K.; Leas, B.; Jepson, C.; Aysola, J.; Cohen, J.B.; Flores, E.; Harhay, M.O.; Schmidt, H.; Weissman, G.E. The Impact of Health Care Algorithms on Racial and Ethnic Disparities: A Systematic Review. Ann. Intern. Med. 2024, 177, 484–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dailey, J. Algorithmic Bias: AI and the Challenge of Modern Employment Practices. UC Law Bus. J. 2025, 21, 215–240. [Google Scholar]

- Danks, D.; London, A.J. Algorithmic Bias in Autonomous Systems. In Proceedings of the 26th International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI), Melbourne, Australia, 19–25 August 2017; pp. 4691–4697. [Google Scholar]

- Bolukbasi, T.; Chang, K.W.; Zou, J.; Saligrama, V.; Kalai, A. Man is to Computer Programmer as Woman is to Homemaker? Debiasing Word Embeddings. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Barcelona, Spain, 5–10 December 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Obermeyer, Z.; Powers, B.; Vogeli, C.; Mullainathan, S. Dissecting Racial Bias in an Algorithm Used To Manage the Health of Populations. Science 2019, 366, 447–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedler, S.; Scheidegger, C.; Venkatasubramanian, S.; Choudhary, S.; Hamilton, E.P.; Roth, D. A Comparative Study of Fairness-Enhancing Interventions in Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, New York, NY, USA, 29–31 January 2019; pp. 329–338. [Google Scholar]

- Frederickson, G. The State of Social Equity in American Public Administration. Natl. Civ. Rev. 2005, 94, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guy, M.E.; McCandless, S.A. Social Equity: Its Legacy, Its Promise. Public Adm. Rev. 2012, 72, S5–S13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kordzadeh, N.; Ghasemaghaei, M. Algorithmic Bias: Review, Synthesis, and Future Research Directions. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2022, 31, 388–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Standards and Technology. Artificial Intelligence Risk Management Framework (AI RMF 1.0); Technical Report NIST AI 100-1; NIST: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- IEEE Std 7003™–2024; IEEE Standard for Algorithmic Bias Considerations. IEEE Systems and Software Engineering Standards Committee: New York, NY, USA, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Alderman, J.E.; Palmer, J.; Laws, E.; McCradden, M.D.; Ordish, J.; Ghassemi, M.; Pfohl, S.R.; Rostamzadeh, N.; Cole-Lewis, H.; Glocker, B. Tackling Algorithmic Bias and Promoting Transparency in Health Datasets: The STANDING Together Consensus Recommendations. Lancet Digit. Health 2025, 7, e64–e88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schelter, S.; Lange, D.; Schmidt, P.; Böhm, S. Automating Large-Scale Data Quality Verification. In Proceedings of the IEEE ICDE, Paris, France, 16–18 April 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, S.E.; Dorn, C.; Park, D.J.; Matheny, M.E. Emerging Algorithmic Bias: Fairness Drift as the Next Dimension of Model Maintenance and Sustainability. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2025, 32, 845–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquino, Y.S.J.; Carter, S.M.; Houssami, N.; Braunack-Mayer, A.; Win, K.T.; Degeling, C.; Wang, L.; Rogers, W.A. Practical, Epistemic, and Normative Implications of Algorithmic Bias in Healthcare AI: A Qualitative Study of Expert Perspectives. J. Med. Ethics 2025, 51, 420–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soleimani, M.; Intezari, A.; Arrowsmith, J.; Pauleen, D.J.; Taskin, N. Reducing AI Bias in Recruitment and Selection: An Integrative Grounded Approach. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2025, 36, 2480–2515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pessach, D.; Shmueli, E. Algorithmic Fairness. In Machine Learning for Data Science Handbook; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 867–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebru, T.; Morgenstern, J.; Vecchione, B.; Wortman Vaughan, J.; Wallach, H.; Daumé, H., III; Crawford, K. Datasheets for Datasets. Commun. ACM 2021, 64, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, M.; Wu, S.; Zaldivar, A.; Barnes, P.; Vasserman, L.; Hutchinson, B.; Spitzer, E.; Raji, I.D.; Gebru, T. Model Cards for Model Reporting. In Proceedings of the ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency (FAT*), Atlanta, GA, USA, 29–31 January 2019; pp. 220–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neil, C. Weapons of Math Destruction: How Big Data Increases Inequality and Threatens Democracy; Crown: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Fraile-Rojas, B.; De-Pablos-Heredero, C.; Mendez-Suarez, M. Female Perspectives on Algorithmic Bias: Implications for AI Researchers and Practitioners. Manag. Decis. 2025, 63, 3042–3065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittelstadt, B.; Allo, P.; Taddeo, M.; Wachter, S.; Floridi, L. The Ethics of Algorithms: Mapping the Debate. Big Data Soc. 2016, 3, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jobin, A.; Ienca, M.; Vayena, E. The Global Landscape of AI Ethics Guidelines. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2019, 1, 389–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachter, S.; Mittelstadt, B.; Floridi, L. Why a Right to Explanation of Automated Decision-Making Does Not Exist in the GDPR. Int. Data Privacy Law 2017, 7, 76–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonas, E.; Schleier-Smith, J.; Sreekanti, V.; Tsai, C.C.; Khandelwal, A.; Pu, Q.; Shankar, V.; Carreira, J.; Krauth, K.; Yadwadkar, N.; et al. Serverless Computing: State of the Art and Research Challenges. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1902.03383. [Google Scholar]

- Hardt, M.; Price, E.; Srebro, N. Equality of Opportunity in Supervised Learning. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Barcelona, Spain, 5–10 December 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Dressel, J.; Farid, H. The Accuracy, Fairness, and Limits of Predicting Recidivism. Sci. Adv. 2018, 4, eaao5580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Nam, A.; Lake, E.; Nudell, J.; Quartey, M.; Mengesha, Z.; Toups, C.; Rickford, J.R.; Jurafsky, D.; Goel, S. Racial Disparities in Automated Speech Recognition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 117, 7684–7689. [Google Scholar]

- Cowgill, B.; Dell’Acqua, F.; Matz, S. The Managerial Effects of Algorithmic Fairness Activism. In AEA Papers and Proceedings; American Economic Association: Nashville, TN, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Panch, T.; Mattie, H.; Atun, R. Artificial Intelligence and Algorithmic Bias: Implications for Health Systems. J. Glob. Health 2019, 9, 020318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johanson, G.A.; Brooks, P.G. Initial scale development: Sample size for pilot studies. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2010, 70, 394–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertzog, M.A. Considerations in determining sample size for pilot studies. Res. Nurs. Health 2008, 31, 180–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Teijlingen, E.; Hundley, V. How large should a pilot study be? Soc. Res. Updat. 1998, 35, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Sambasivan, N.; Kapania, S.; Highfill, E.; Akrong, D.; Paritosh, P.; Aroyo, L. Everyone Wants To Do the Model Work, Not the Data Work: Data Cascades in High-Stakes AI. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, New York, NY, USA, 8–13 May 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raji, I.D.; Smart, A.; White, R.N.; Mitchell, M.; Gebru, T.; Hutchinson, B.; Smith-Loud, J.; Theron, D.; Barnes, P. Closing the AI Accountability Gap: Defining, Evaluating, and Achieving Audits. In Proceedings of the ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency (FAccT), New York, NY, USA, 27–30 January 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Paper | Research Question | Method & Citation |

|---|---|---|

| Algorithmic Bias: Review, Synthesis, and Future Research Directions | What are the origins, effects, and mitigation strategies of algorithmic bias? | Systematic review [13] |

| Algorithmic Bias: AI and the Challenge of Modern Employment Practices. UC Law Business Journal | How does algorithmic hiring impact social justice and employment law? | Legal analysis, case study [6] |

| The Impact of Health Care Algorithms on Racial and Ethnic Disparities: A Systematic Review. Annals of Internal Medicine | How do healthcare algorithms affect racial and ethnic disparities? | Systematic review [5] |

| IEEE Standard for Algorithmic Bias Considerations | What is a comprehensive standard for identifying and mitigating algorithmic bias? | Standards development (IEEE Standards Association [15]) |

| Reducing AI Bias in Recruitment and Selection: An Integrative Grounded Approach | How can AI bias be reduced in recruitment and selection processes? | Grounded theory [20] |

| Algorithmic Fairness | How can algorithmic fairness be defined, measured, and achieved? | Technical survey and taxonomy [21] |

| Question | Statement | Mean | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | Algorithms in everyday tech can be biased | 3.21 | 0.62 | [2.98, 3.44] |

| 7 | Understands how algorithmic biases are introduced | 2.89 | 0.77 | [2.60, 3.18] |

| 8 | Confident in personal knowledge about bias | 2.46 | 0.82 | [2.15, 2.77] |

| 9 | Has read/heard examples of algorithmic bias | 2.64 | 0.77 | [2.35, 2.93] |

| 10 | Considers self informed about algorithmic-bias issues | 2.46 | 0.73 | [2.19, 2.73] |

| 11 | Biased algorithms can lead to unfair treatment | 3.11 | 0.68 | [2.86, 3.36] |

| 12 | Algorithmic bias negatively affects people’s lives | 3.11 | 0.68 | [2.86, 3.36] |

| 13 | Bias is a serious fairness issue | 3.07 | 0.60 | [2.85, 3.29] |

| 14 | Worried about harm to vulnerable communities | 3.07 | 0.77 | [2.78, 3.36] |

| 15 | Biased algorithms undermine fairness | 3.26 | 0.52 | [3.07, 3.45] |

| 16 | Bias can be reduced via careful design/testing | 3.04 | 0.68 | [2.79, 3.29] |

| 17 | Support regulations ensuring algorithmic fairness | 3.39 | 0.56 | [3.18, 3.60] |

| 18 | Developers are responsible for minimizing bias | 3.36 | 0.55 | [3.15, 3.57] |

| 19 | Endorse technical solutions to reduce bias | 3.07 | 0.70 | [2.81, 3.33] |

| 20 | Endorse transparency about algorithms and data | 3.32 | 0.66 | [3.07, 3.57] |

| 21 | Important that technology used is bias-free | 3.14 | 0.58 | [2.92, 3.36] |

| 22 | Would lose trust if a system used biased algorithms | 3.18 | 0.89 | [2.85, 3.51] |

| 23 | Companies should be held accountable for bias | 3.18 | 0.85 | [2.86, 3.50] |

| 24 | Fairness is as important as accuracy | 3.36 | 0.61 | [3.13, 3.59] |

| 25 | Addressing algorithmic bias should be a high societal priority | 3.32 | 0.54 | [3.12, 3.52] |

| Domain | Question | Mean |

|---|---|---|

| Awareness/Knowledge | Q6–Q10 | 2.73 |

| Harms and Fairness | Q11–Q15 | 3.12 |

| Solutions/Regulation | Q16–Q20 | 3.24 |

| Trust and Expectations | Q21–Q23 | 3.17 |

| Prioritization | Q24–Q25 | 3.34 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Alhosban, A.; Gaire, R.; Al-Ababneh, H. Public Perceptions of Algorithmic Bias and Fairness in Cloud-Based Decision Systems. Standards 2026, 6, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/standards6010002

Alhosban A, Gaire R, Al-Ababneh H. Public Perceptions of Algorithmic Bias and Fairness in Cloud-Based Decision Systems. Standards. 2026; 6(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/standards6010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlhosban, Amal, Ritik Gaire, and Hassan Al-Ababneh. 2026. "Public Perceptions of Algorithmic Bias and Fairness in Cloud-Based Decision Systems" Standards 6, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/standards6010002

APA StyleAlhosban, A., Gaire, R., & Al-Ababneh, H. (2026). Public Perceptions of Algorithmic Bias and Fairness in Cloud-Based Decision Systems. Standards, 6(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/standards6010002