Health Education: The “Education Box” of the Fondazione Policlinico Universitario Campus Bio-Medico

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- Individual patient education: consists of sharing information, activities, and coping skills adapted to each patient’s pain experience [19];

- (2)

- (3)

- (1)

- Home education: patient education in the independent use of health devices (VAC—Vacuum-Assisted Closure, the proper management of drains; the Holter pressor; home polysomnography; etc.);

- (2)

- Caregiver education (for geriatric patients, cancer patients, patients with disabilities, etc.);

- (3)

- Education in small and/or large groups (before surgery or post-surgery, e.g., for hip or bariatric surgery).

2. Materials and Methods

- (1)

- The design, creation, and distribution of informative brochures (pre/post-procedure).

- (2)

- The review and formatting of patients’ informative notes (to be attached to standard informed consent forms).

- (3)

- The development, production, and dissemination of clinical tutorial videos (e.g., the home management of drains).

- (4)

- “Education box” events (focused on specific healthcare topics).

- Modify the classic form of clinical education by creating a free public service dedicated to patients, family members, and caregivers.

- Patient engagement: foster an “active patient” model within the care pathway, in alignment with the national plan for chronic diseases [38], promoting a culture of shared decision-making.

- Empowerment through education: address patients’ needs for scientific knowledge, emotional support, and social connection, reducing fear and isolation. Proactively and accessibly provide information to prevent doubts and uncertainties.

- Community and networking: establish collaborations with patient associations and disease-specific organizations to create specialized resources and expand the reach of information and support.

- The creation and distribution of informational materials: develop brochures, video tutorials, and informative notes linked to consent forms.

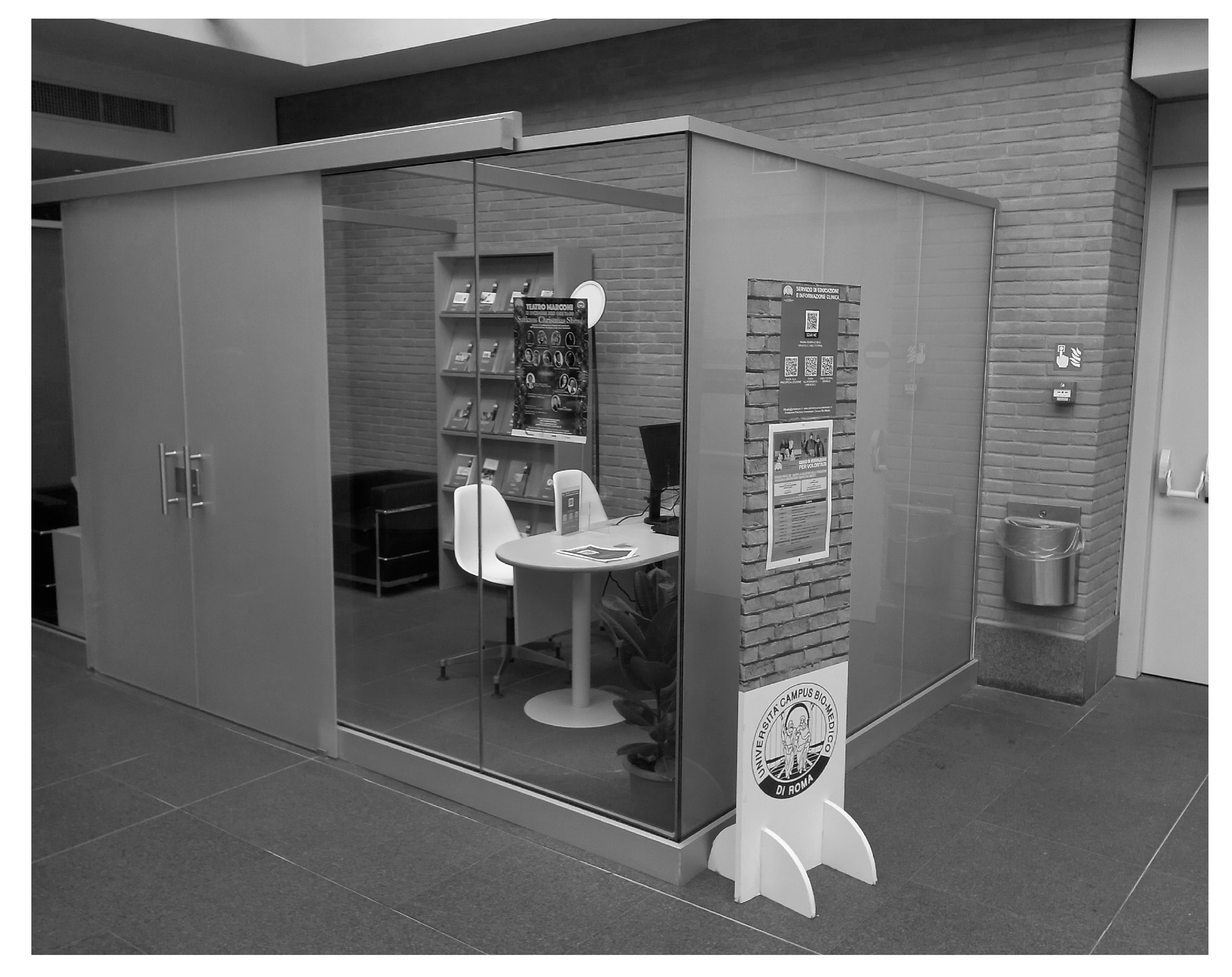

- The creation of a physical interrelational space: provide a welcoming physical environment (distinct from a cold medical office or a crowded inpatient ward) where healthcare professionals can meet with patients’ families or caregivers. This service acts as a space for reception and information, located on the second floor of the foundation, where patients and families can receive reliable information and support to better understand the care provided.

- The promotion of a culture of active patient involvement in therapeutic decisions: advocate for active participation by patients in their treatment decisions.

- Enhance patient education and clinical support, addressing the need for clear and accessible information that fosters awareness and confidence in the care journey.

- Engage 30 patients/family members/caregivers per event.

- Encouraging empathetic and transparent healthcare: deliver healthcare that addresses the informational and emotional needs of patients and their families with empathy and transparency.

3. Implementations

- Educational box events: sessions led by healthcare specialists on topics such as chronic disease management, device handling, prevention strategies, and innovative treatments.

- Information hub: a physical space staffed by FPUCBM volunteers, available to address patient questions and distribute educational brochures and video tutorials.

- Digital access: QR codes linked to a dedicated section of the institutional website, where patients can access infographics and instructional videos.

- Collaboration with associations: working with patient associations to review content included in information notes or information booklets to improve communication quality and the effectiveness of ‘‘health education”.

- Aligns with the principles of Health Technology Assessment (HTA), promoting patient participation in the evaluation of healthcare technologies and ensuring that their needs and preferences are taken into account.

- Contributes to the collection of Patient-Reported Outcomes (PROs), i.e., data on patients’ experiences, which are essential for assessing the effectiveness and impact of care.

- Promotes an approach based on the assessment of the benefits and risks (efficacy and safety) of treatments.

- Promotes integrated care: integrated care models have the potential to improve quality of life, self-care, adherence to medical and mental health treatments, and both mental and physical disease outcomes [39].

- Hospital education plans are based on the care, treatments, and services provided, as well as the needs of the patient population.

- The hospital has a program for patient education in all departments, which includes:

- ○

- Supervision by one or more qualified clinical staff member.

- ○

- Access to educational resources tailored to the care, treatments, and services provided and the needs of the patient population.

- Patient and family education is developed and delivered collaboratively by interdisciplinary staff members.

- The clinical staff providing the education have the subject matter knowledge and communication skills necessary to do so effectively.

4. Outcomes

4.1. Educational Brochures

4.2. Patient Information Notes

- Name of the hospital;

- Name of the test, procedure, or treatment covered by the informed consent;

- Name of the responsible practitioner(s) performing the procedures(s);

- Signature of the patient or designee if the hospital or laws and regulations require a signed consent form;

- Date and time consent is granted by the patient;

- Statement that the procedure was explained to the patient or designee, including benefits, risks, and alternatives;

- The likelihood of success, potential complications, the recovery process, and the possible results of nontreatment;

- The name, signature, and role of the person who explained the procedure to the patient or surrogate.

4.3. Video Tutorial

4.4. Education Box Events

- (1)

- An educational session: led by a healthcare professional (e.g., a doctor, nurse, nutritionist, or psychologist), this phase provides detailed information about the disease, treatment, or care pathway relevant to the theme of the event.

- (2)

- An interactive session: this phase is dedicated to listening to the questions, doubts, and concerns raised by patients, families, and healthcare professionals present.

“I had the opportunity to say it in person that day: you are extraordinary in the way, in the location and in exposing the contents. Unfortunately, you are the only ones who organize events of this kind with the “hunger” for information that all of us users of the health service have. Congratulations, keep it up!”

5. Discussion

- (1)

- The improved acquisition of useful feedback from participants. The evaluation of the impact of training: the objective is to develop a digital system for assessing both the effectiveness and the quality of the training provided.

- (2)

- Healthcare professionals. Optimize physicians’ time: the goal is to free up valuable time for physicians, enabling them to focus more on fostering meaningful connections with patients during consultations. By offering clear guidance to informational resources, such as directing patients to a dedicated box or its digital content, physicians can ensure that patients have access to video tutorials and educational materials. These resources allow patients to deepen their understanding of their condition and revisit the explanations provided by the physician at their convenience. This approach empowers physicians to prioritize the relational aspects of care while maintaining the quality and accessibility of the information delivered.

- (3)

- Clinical research. Enhancing awareness of clinical trials: the objective is to improve patients’ understanding and awareness of clinical trials by ensuring they are provided with all essential information, including any details they may have overlooked or forgotten to inquire about during their consultation. By offering accessible resources that support patients in comprehending their involvement, this initiative seeks to reduce clinical trial dropout rates, fostering a sense of confidence and support throughout their therapeutic journey.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| FPUCBM | Fondazione Policlinico Universitario Campus Bio-Medico |

| JCI | Joint Commission International |

| HTA | Health Technology Assessment |

| PROs | Patient-Reported Outcomes |

| VAC | Vacuum-Assisted Closure |

References

- Pleshkan, V. A systematic review: Clinical education and preceptorship during nurse practitioner role transition. J. Prof. Nurs. 2024, 50, 16–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higuchi, D.; Echigo, A. Clinical education-related stressors and emotional states during clinical education among physical therapy students. Physiother. Theory Pract. 2023, 39, 405–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, H.; Shim, S.; Lee, Y.M. A scoping review on adaptations of clinical education for medical students during COVID-19. Prim. Care Diabetes 2021, 15, 958–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bachmann, C.; Roschlaub, S.; Harendza, S.; Keim, R.; Scherer, M. Medical students’ communication skills in clinical education: Results from a cohort study. Patient Educ. Couns. 2017, 100, 1874–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofer, D.; Gartenmann, S.J.; Wiedemeier, D.B.; Attin, T.; Schmidlin, P.R. The effect of clinical education on optimizing self-care by dental students in Switzerland. Swiss Dent. J. 2022, 132, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolden, M.; Flom-Meland, C.; Gusman, L.N.; Drevyn, E.; McCallum, C. Determining the Optimal Length of Clinical Education Experiences: Surveying Doctor of Physical Therapy Academic and Clinical Faculty. J. Phys. Ther. Educ. 2024, 38, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stenberg, U.; Vågana, A.; Flink, M.; Lynggaard, V.; Fredriksen, K.; Fredrik Westermann, K.; Gallefosse, F. Health economic evéaluations of patient education interventions a scoping review of the literature. Patient Educ. Couns. 2018, 101, 1006–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrosio, L.; Senosiain Garcia, J.M.; Riverol Fernandez, M.; Anaut Bravo, S.; Diaz De Cerio Ayesa, S.; Ursua Sesma, M.E.; Caparrós, N.; Portillo, M.C. Living with chronic illness in adults: A concept analysis. J. Clin. Nurs. 2015, 24, 2357–2367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulman-Green, D.; Jaser, S.; Martin, F.; Alonzo, A.; Grey, M.; McCorkle, R.; Redeker, N.S.; Reynolds, N.; Whittemore, R. Processes of self-management in chronic illness. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2012, 44, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, S.; Steed, L.; Mulligan, K. Self-management interventions for chronic illness. Lancet 2004, 364, 1523–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagioti, M.; Richardson, G.; Small, N.; Murray, E.; Rogers, A.; Kennedy, A.; Newman, S.; Bower, P. Self-management support interventions to reduce health care utilisation without compromising outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2014, 14, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bajpai, S.; Semwal, M.; Bajpai, R.; Car, J.; Ho, A.H.Y. Health professions’ digital education: Review of learning theories in randomized controlled trials by the digital health education collaboration. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019, 21, e12912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Dai, H.; MJJ van der Kleij, R.; Lim, R.; Wu, H.; Hallensleben, C.; Willems, S.H.; Chavannes, N.H. Digital Health Education for Chronic Lung Disease: Scoping Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2025, 27, e53142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulrich, M. How Hospitals Evaluate Patient Education Programs. In Proceedings of the National Conference on Hospital-Based Patient Education, Chicago, IL, USA, 9–10 August 1976; Center for Disease Control (DHEW/PHS): Atlanta, GA, USA, 1976; pp. 467–483. [Google Scholar]

- Loevinsohn, B.P. Health education interventions in developing countries: A methodological review of published articles. Int. J. Epidemiol. 1990, 19, 788–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews-Cooper, I.N.; Kozachik, S.L. How Patient Education Influences Utilization of non-pharmacological Modalities for Persistent Pain Management: An Integrative Review. Pain Manag. Nurs. 2020, 21, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainpradub, K.; Sitthipornvorakul, E.; Janwantanakul, P.; Van der Beek, A.J. Effects of education on non-specific neck and low back pain: A meta-analysis of randomized trials. Man. Ther. 2016, 22, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehl-Madrona, L.; Mainguy, B.; Plummer, J. Integration of complementary and alternative medicine therapies into primary-care pain management for opiate reduction in a rural setting. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2016, 22, 621–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engers, A.J.; Jellema, P.; Wensing, M.; Van der Windt, D.A.; Grol, R.; Van Tulder, M.W. Individual patient education for low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2008, 1, CD004057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltran-Alacreu, H.; Lopez-de-Uralde-Villanueva, I.; Fernandez-Carnero, J.; La-Touche, R. Manual therapy, therapeutic patient education, and therapeutic exercise, an effective multimodal treatment of nonspecific chronic neck pain: A randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2015, 94, 887–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, A.; Forget, M.; St George, K.; Fraser, M.M.; Graham, N.; Perry, L.; Burnie, S.J.; Goldsmith, C.H.; Haines, T.; Brunarski, D. Patient education for neck pain. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2012, 3, CD005106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosio, D.; Lin, E.H. Effects of a pain education program in complementary and alternative medicine treatment utilization at a VA medical center. Complement. Ther. Med. 2015, 23, 413–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroon, F.B.; Van der Burg, L.R.; Buchbinder, R.; Osborne, R.H.; Johnston, R.V.; Pitt, V. Self -management education programs for osteoarthritis (Review). Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, 1, CD008963. [Google Scholar]

- Parlar, S.; Fadiloglu, C.; Argon, G.; Tokem, Y.; Keser, G. The effects of selfpain management on the intensity of pain and pain management methods in arthritic patients. Pain Manag. Nurs. 2013, 14, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, E.H.; Whistance, R.N.; Phillips, K.; Morgan, B.; Savage, K.; Lewis, V.; Kelly, M.; Blazeby, J.M.; Kinnersley, P.; Edwards, A. Systematic review and meta-analysis of audio-visual information aids for informed consent for invasive healthcare procedures in clinical practice. Patient Educ. Couns. 2014, 94, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pensieri, C.; Saccoccia, S.; De Benedictis, A.; Alloni, R. Adult Patient Education: A readability analysis of Hospital University Campus Bio-Medico’s Patients information Material (PIMs). J. Educ. Cult. Psychol. Stud. 2022, 25, 103–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadam, R.A. Informed consent process: A step further towards making it meaningful! Perspect. Clin. Res. 2017, 8, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mettarikanon, D.; Tawanwongsri, W.; Jaruvijitrattana, P.; Sindhusen, S.; Charoenchitt, S.; Manunyanon, P. Efficacy of informed consent process using educational videos for skin biopsy procedures. Contemp. Educ. Technol. 2023, 15, ep477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, A.W.; Alikhan, A.; Cheng, L.S.; Schupp, C.; Kurlinkus, C.; Eisen, D.B. Portable video media for presenting informed consent and wound care instructions for skin biopsies: A randomized controlled trial. Br. J. Dermatol. 2010, 163, 1014–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawdy, K.; Bonin, K.; Russell, S.; Ryzynski, A.; Harth, T.; Townsend, C.; Liu, S.; Chu, W.; Cheung, P.; Chung, H.; et al. Developing and evaluating multimedia patient education tools to better prepare prostate-cancer patients for radiotherapy treatment (randomized study). J. Cancer Educ. 2018, 33, 551–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, A.; Salsi, G.; Ragusa, A.; Ghi, T.; Pacella, G.; Rizzo, N.; Pilu, G. Caregiver’s satisfaction with a video tutorial for shoulder dystocia management algorithm. J. Obs. Gynaecol. 2015, 35, 461–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sommer, C.; Bachmann, L.M.; Handzic, A.; Iselin, K.C.; Sanak, F.; Pfaeffli, O.; Kaufmann, C.; Thiel, M.A.; Baenninger, P.B. The effect of a video tutorial to improve patients’ keratoconus knowledge—A randomized controlled trial and meta-analysis of published reports. Front. Ophthalmol. 2022, 2, 997257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Done, M.L.; Lee, A. The use of a video to convey preanesthetic information to patients undergoing ambulatory surgery. Anesth. Analg. 1998, 87, 531–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grilo, A.M.; Ferreira, A.C.; Ramos, M.P.; Carolino, E.; Pires, A.F.; Vieira, L. Effectiveness of educational videos on patient’s preparation for diagnostic procedures: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev. Med. Rep. 2022, 28, 101895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Pan, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Song, X.; Zhou, Y. Evaluating AI-generated patient education materials for spinal surgeries: Comparative analysis of readability and DISCERN quality across ChatGPT and deepseek models. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2025, 198, 105871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calixte, R.; Rivera, A.; Oridota, O.; Beauchamp, W.; Camacho-Rivera, M. Social and demographic patterns of health-related internet use among adults in the United States: A secondary data analysis of the health information national trends survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evangelista, L.S.; Rasmusson, K.D.; Laramee, A.S.; Barr, J.; Ammon, S.E.; Dunbar, S.; Ziesche, S.; Patterson, J.H.; Yancy, C.W. Health literacy and the patient with heart failure—Implications for patient care and research: A consensus statement of the Heart Failure Society of America. J. Card. Fail. 2010, 16, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministero della Salute (Italian Ministry of Healthcare). Piano Nazionale della Cronicità; Direzione Generale della Programmazione Sanitaria (National Chronic Care Plan. General Directorate of Health Planning): Rome, Italy, 2016. Available online: https://osservatoriocronicita.it/images/PDF/Piano_Nazionale_cronicit.pdf (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- Coates, D.; Coppleson, D.; Schmied, V. Integrated physical and mental healthcare: An overview of models and their evaluation findings. Int. J. Evid.-Based Healthc. 2020, 18, 38–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joint Commission International; Accreditation Standards for Hospitals; Including Standards for Academic Medical Center Hospitals. The Joint Commission Resources; Joint Commission International: Oakbrook Terrace, IL, USA, 2024; pp. 160–161. ISBN 978-1-63585-347-6. [Google Scholar]

- Lambert, K.; Bernes, S.; Buxton, N.; Gogebakan, N.; Hennen, G.T.; Caswell, G.F. Designing Better Resources: Consumer Experiences, Priorities and Preferences Regarding Contemporary Nutrition Education Materials. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2025, 38, e70041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wilson, E.A.H.; Wolf, M.S. Working Memory and the Design of Health Materials: A Cognitive Factors Perspective. Patient Educ. Couns. 2009, 74, 318–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, K.; Mansfield, K.; Mullan, J. How Do Patients and Carers Make Sense of Renal Dietary Advice? A Qualitative Exploration. J. Ren. Care 2018, 44, 238–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morony, S.; McCaffery, K.J.; Kirkendall, S.; Jansen, J.; Webster, A.C. Health Literacy Demand of Printed Lifestyle Patient Information Materials Aimed at People With Chronic Kidney Disease: Are Materials Easy to Understand and Act on and Do They Use Meaningful Visual Aids? J. Health Commun. 2017, 22, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patterson, C.; Teale, C. Influence of Written Information on Patients’ Knowledge of Their Diagnosis. Age Ageing 1997, 26, 41–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chesser, A.K.; Keene Woods, N.; Smothers, K.; Rogers, N. Health Literacy and Older Adults: A systematic review. Gerontol. Geriatr. Med. 2016, 2, 233372141663049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, A.; Sandford, J.; Tyndall, J. Written and Verbal Information Versus Verbal Information Only for Patients Being Discharged From Acute Hospital Settings to Home. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2003, 4, Cd003716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Target | N° |

|---|---|

| Public | 86 |

| Internal staff | 9 |

| Tot | 95 |

| Education Box Events in the 2024 |

|---|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pensieri, C.; Rossi, V.; Alloni, R. Health Education: The “Education Box” of the Fondazione Policlinico Universitario Campus Bio-Medico. Standards 2025, 5, 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/standards5020015

Pensieri C, Rossi V, Alloni R. Health Education: The “Education Box” of the Fondazione Policlinico Universitario Campus Bio-Medico. Standards. 2025; 5(2):15. https://doi.org/10.3390/standards5020015

Chicago/Turabian StylePensieri, Claudio, Veronica Rossi, and Rossana Alloni. 2025. "Health Education: The “Education Box” of the Fondazione Policlinico Universitario Campus Bio-Medico" Standards 5, no. 2: 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/standards5020015

APA StylePensieri, C., Rossi, V., & Alloni, R. (2025). Health Education: The “Education Box” of the Fondazione Policlinico Universitario Campus Bio-Medico. Standards, 5(2), 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/standards5020015