3.2. Selected Aging Perspectives

Although data reveal that approximately 80% of older adults or those 65 years of age or older have at least one chronic health condition, and about 50% have at least two or more of these conditions, as well as being at risk for infectious diseases and injuries such as falls, contrary to the stereotyped myth that aging is synonymous with an overall health decline, most adults are found to be healthy and can function at a high level. As well, research shows neither muscle function, nor memory loss is inevitable, and that physical and cognitive power does not need to decline over time, as previously believed.

Rather, while acknowledging relevant age-associated health changes do occur, positive aspects of aging, and how to prevent or deal with these inherent physiological changes, as well as any health problems that are incurred over time, provides an alternative perspective known as ‘successful aging’, which is seen as a process, as well as an active state of being. Indeed, although many myths and misconceptions about aging as a state of decline clearly prevail, this idea of ‘successful aging’ is not merely an academic one, because if one examines the leading causes of death among adults ages 65 and older, which are heart disease, cancer, stroke, chronic lower respiratory diseases, Alzheimer’s disease, diabetes, influenza and pneumonia, and unintentional injury, none of these health conditions are simply inevitable consequences of aging [

15]. Indeed, while it is true most chronic illnesses, once diagnosed in older adults are generally incurable, and can worsen over time, the key causes of most of these chronic illnesses and their morbidity rates as demonstrated in most recent nationwide and global public health research sites and data, are lifestyles and behaviors, changeable environmental agents, modifiable factors such as poverty, and other social factors, rather than genetic factors-once attributed an even role in determining longevity (e.g., smoking behaviors, eating behaviors). Additionally, most underlying causes or risk factors are amenable to prevention, intervention, remediation, elimination, or palliation, even if they are genetic (e.g., mastectomy for those with certain breast cancer genes, trauma prevention in those predisposed to genetically determined forms of osteoarthritis). Richardson et al. [

16] also note that it is common for people with chronic conditions to report their health as good, even though models of healthy aging do not account for this.

Consequently, although many examples of debilitated older adults can be found, data show the majority of the older population to be neither debilitated, nor disabled. They may clearly be in their eighties but remain actively employed, they may be serving at the community level in volunteer endeavors, or involved in creative tasks, politics, education and other endeavors. Other data show that much of the innovation, beauty, science, and laws that prevail today are due to the efforts of talented or motivated people, who pushed themselves and developed their potentials, even though they were already deemed to be ‘senior’ citizens.

It can further be shown that many older adults, not only exhibit a complete ‘lack’ of any identifiable or seriously disabling disease or exposure to trauma, but that they may be more fit and functional than those in their 30s as a result of adopting a sound lifestyle. Even though bodily systems do still change over time, additional research shows a steady rate of decline from age 30 to 90, rather than any steep or rapid decline. These changes may also not occur simultaneously in all body systems, and even if they do change and influence the onset or risk of disease and dysfunction, these changes may still be reversible, e.g., abnormal glucose levels can be impacted favorably in many cases of pre-diabetes.

On the contrary, since change is a constant in life, regardless of the stage of development or growth, a philosophy that enables the individual to adapt to any special challenges may yet foster a meaningful existence, rather than an inevitable and painful declining, and depressive existence, even though there is much more research on aging that deals with patients, and their hospitalization or experience in the nursing home than their longevity and health attributes. Unfortunately, gerontology, or the study of aging, largely focuses on the negative aspects of aging, while geriatrics is concerned with treating problems related to aging, rather than preventing these, as well as on disability or senescence.

However, in 1984 John D and Catherine T. MacArthur gathered a group of scholars to develop a new set of insights regarding aging. Their mission was to stress the positive aspects of aging and to examine factors permitting certain individuals to function effectively, both physically and mentally in old age. More recently, Thompson et al. [

17] found that even though polynomial regression of cross-sectional data obtained from 1546 individuals aged 21–100 years suggested a possible age-associated accelerated deterioration in physical and cognitive functioning, averaging 1.5–2 standard deviations over the adult lifespan, there appeared to be a linear improvement of about 1 standard deviation in various mental health attributes over the same life period.

3.3. Successful Aging

As reported in an initial publication in 1987 by the MacArthur group detailing the concept of ‘successful aging’ that followed their research efforts to better understand factors influencing positive health outcomes, despite aging, the idea put forth was that one did not have to age in a negative sense, but one could grow old, while maintaining their health, strength, and vitality, and could hence be deemed to be a successful ‘ager’ [

18]. Since that time many hundreds if not thousands of articles related to this 1987 publication, and its dominant theme, along with its theoretical correlates have discussed this concept of ‘successful aging’, also known as healthy, active, productive, optimal, vital, or positive aging [

3,

19,

20], among other definitions. This ever growing body of research continues to enlarge upon and expand on the early concept of ‘successful aging’, a viewpoint of aging built on the idea of harnessing the untapped resources of middle-aged adults and older individuals to enhance their well-being as they aged. It was a view encompassing attempts to maximize the potential of the aging adult to adapt to change, despite any physiological decline, and in so doing, to boost their chances of increasing their life satisfaction, mastery, growth, and longevity, as key components of ‘successful aging’, rather than succumbing to disablement and depression.

One overriding tenet of this idea was that aging in the negative sense was not inevitable, but was more likely than not to depend at least partly, on individual choices and behaviors, as well as effort. A second premise was that a broad focus of health issues, as well as more efficacious health policies, basic education that promotes health literacy, quality housing, medical care, and appropriate employment opportunities, where desirable, might substantially reduce impediments to a meaningful and high quality experience in later life, thus promoting the idea of ‘successful aging’ or aging well through proactive adaptation processes [

3] as an achievable goal.

However, Cosco et al. [

11] noted that even though almost half a century had elapsed since the inception of the term ‘successful aging’, no clear definition and hence no unified understanding of the underlying framework and concepts underpinning ‘successful aging’ could be readily identified. After conducting a systematic review using MedLine, PsycInfo, CINAHL, EMBASE, and ISI Web of Knowledge and a search that focused on quantitative operational definitions of ‘successful aging’, 105 such definitions, across 84 studies, using unique models were observed. A further analysis showed 92.4% or 97 studies included physiological constructs (e.g., physical functioning), 49.5% or 52, engagement constructs (e.g., involvement in voluntary work), 48.6% or 51 well-being constructs (e.g., life satisfaction), 25.7% or 27 personal resources (e.g., resilience), and 5.7% or 6 focused on extrinsic factors (e.g., finances). Thirty-four definitions consisted of a single construct, 28 of two constructs, 27 of three constructs, 13 of four constructs, and two of five constructs. The operational definitions utilized in the included studies identified between <1% and >90% of study participants as ‘successfully aging’. Based on these results, it appeared that the concept of ‘successful aging’ was clearly not a universal concept, and possibly one that was not always attainable, but its definition depended on what was being studied, who was being studied, or how the research was operationalized, among other factors. The idea that ‘successful aging’ is a multidimensional one, could consequently not be validated, and with no consistent research approach, no consensual definition of ‘successful aging’ or a framework for practice could be identified.

Earlier, Depp et al. [

21] who similarly examined definitions and predictors of ‘successful aging’ using a large set of quantitative studies found 28 studies with 29 different definitions that met the researchers criteria. Even though most investigations used large samples of community-dwelling older adults, the mean reported proportion of successful agers was 35.8%, but this figure varied widely, and may have depended on the nature of the study, and the multiple components of ‘successful aging’ definitions identified. The most frequent favorable correlates of the various definitions of ‘successful aging’ were age (young-old), nonsmoking, and absence of disability, arthritis, and diabetes. Moderate support was also found for a positive role of greater physical activity, more social contacts, better self-rated health, an absence of depression and cognitive impairment, and fewer medical conditions in fostering ‘successful aging’. These aforementioned data results were mostly based on examining older adults without disability who still portrayed quite a low response to the extent of perceiving they had aged successfully.

However, regardless of definition and clarification of what constitutes ‘successful aging’, Tesch-Romer and Wahl [

22] have argued that even if changing environmental settings, societal policies, and fostering individual life styles will significantly extend the number of healthy life years, recent epidemiological research confirms the dilemma that the ongoing extension of life expectancy prolongs not only the years in good health, but also those in poor health. This group thus argued that Rowe and Kahn’s ‘successful aging’ model 2 is still not able to cover the emerging linkage between increasing life expectation and aging with disability and care needs, and presents a clear limitation in this regard. Instead, this group suggested a set of propositions be forged towards a more comprehensive model of ‘successful aging’, and one that would capture desirable living situations including those that encompass aging adults with disabilities and specific care needs. They consequently went on to describe a number of individual, environmental, and care related strategies and resources for promoting autonomy and life quality in the face of disabilities and care needs in late life, putting emphasis on inter-individual differences and social inequalities, and that was designed to expand upon the traditional concept of successful aging, but to do this in light of current aging science and aging population needs.

Although Gopinath et al. [

23] found physical activity helped to foster ‘successful aging’, this group who attempted to determine the features of ‘successful aging’ through interviewer-administered questionnaire, still classified this concept as the absence of: depressive symptoms, disability, cognitive impairment, respiratory symptoms and systemic conditions (e.g., cancer, coronary artery disease), thus excluding almost all aging persons from achieving this state.

Yet, other determinants of ‘successful aging’ that have emerged from the research may or may not be helpful. These include, the adoption of proactive lifestyles that enhance health, actions that correct for health-associated behavioral risks, making healthy choices the only choice, and participating in stimulating cognitive activities. Other theories imply that eliminating factors that increase the risk for disability, or in fact increase its rate of progress-if present-such as stress, substance abuse, and infections, while fostering high quality social support, community based programs, financial security, and in the case of the individual having them adopt a positive, rather than a negative self-concept [

4] are likely to be very influential in efforts designed to foster more successful rather than less successful aging outcomes. The availability of appropriate information and other resources, as well as uplifting opportunities to engage with others, may similarly enable more ‘successful aging’ across the lifespan [

4], regardless of health status, than would otherwise be experienced.

The concept of ‘successful aging’ itself, however, is currently ill defined and may mean different things to different persons, for example those from different cultures may not emphasize the same subjective or objectively defined attributes that are perceived as elements of ‘successful aging’ [

4,

5]. As well, a high degree of diversity in the perception of what this concept would mean personally, and whether this can be attained, if desirable may prevail, regardless of culture, health, and extrinsic factors. The studied attributes of ’successful aging’ are also highly heterogeneous and range from ‘having good health’, to ‘having a sense of purpose’, and autonomy, among others [

4], such as the absence of disease and disability [

5], and the ability to maintain physical and cognitive functioning [

5]. Adding further confusion is research showing these attributes and others can readily fluctuate depending on age-wherein ‘successful’ agers tended to be younger and report more frequent engagement in lifestyle activities than older subjects [

7], gender [

5], living circumstances [

9], and the extent of any disability and pain [

9], among other factors.

In addition, another term related to the concept of ‘successful aging’, namely, ‘healthy aging’, similarly hosts a number of definitions and components of well-being that differ depending on the stance of the researchers, and their specialty. This latter concept also differs somewhat from that of ‘successful aging’, and is suggested to denote the ability of the individual to modify, reassess and redefine oneself-but does not preclude disease states. Resilience, adaptation and compensation are other important characteristics of healthy aging that appear valid, but again these may vary dependent on the values held by different societies, as well as societal and individual expectations, and the role of family, social engagement, among other factors. Another view is that if disease is seen as a normal part of aging-rather than modeling ‘successful aging’ on the basis of freedom from disease, Amin [

4] implies it may be fruitless to identify whether any universal set of ‘successful aging’ constructs prevail. Rather, the individual’s perception and how they define ‘successful aging’ or ‘aging well’ must be uncovered through careful interactions and communication efforts.

In short, the concept of ‘successful’ or healthy aging, or that of a ‘good old age’ is depicted as multidimensional. Its scope and meaning may depend however on what premises researchers decide to test, the type of research questions posed, the sample numbers and characteristics. Results may also depend on the individual and her perceptions, as well as how practitioners and researchers view this concept [

3]. However, despite a myriad of views, and discrepancies among the diverse biomedical, psychological, and lay perspectives [

21], it appears that to promote ‘successful aging’, something more than personal attributes and understandings can determine this life outcome. For example, an empathetic provider-patient relationship and access to quality care and living conditions and taking cultural preferences and views into account can help even those who are disabled to be more successful than not. As well, a focus on the socio-emotional aspects of health, as well as the physical aspects of health will clearly be more helpful than not, regardless of level of ability or disability.

Elements of ‘successful aging’ may also include sound nutrition practices, an active lifestyle, having a degree of financial security, and sound sleep hygiene strategies, and in our view are just as relevant to those with health conditions as those who have no health disability. Efforts to reduce or minimize anxiety, depression, and low self-concept are additional strategies that can be applied, regardless of health status. According to findings by Richardson et al. [

16] who examined how resilience relates to how people consider themselves to be well, regardless of their adverse health condition, the experience of adversity is influenced by context and meaning, findings which support a broader version of resilience that incorporates vulnerabilities, and should not undermine an older person’s sense of a resilient self.

Zanjari et al. [

14] who examined 76 topical articles eligible for inclusion in an integrative review, found 14 subcategories and 5 main categories of ‘successful aging’ to prevail, including social well-being, psychological wellbeing, physical health, spirituality and transcendence, and the environment and economic security. Another study by Parslow et al. [

24] found factors measuring mental, physical and social health can all contribute significantly and independently to ‘successful aging’ and that the presence of chronic health conditions does not necessarily preclude high levels of well-being in older individuals. Another view is that disease and disability might be viewed as a normal part of aging, and thus freedom from disease or longevity is not necessarily of high import to the same degree in all cultures [

4].

In the next section, we argue that contrary to early beliefs that saw ‘successful aging’ as a state where the individual was disease free, attaining this state is in the eyes of the individual, and its attainment should not be neglected in the presence of an irreversible disease.

3.4. Osteoarthritis

Osteoarthritis is a painful disabling joint disease that predominantly affects more than half of those adults who are 65 years of age or older. An incurable disease that often affects more than one joint, the condition can be extremely debilitating and disabling is one where few risk free treatment strategies exist. Moreover, medications applied to alleviate disease symptoms are often contra-indicated or induce unwarranted side-effects, and surgery is not always effective or warranted. Given that many with this physical condition also show signs of depression [

25], a diminished work capacity, restrictions of social activities [

26], and most have one or more comorbid chronic diseases, and/or are overweight or obese, and all these components of the illness interact to often increase the severity of the condition [

26], the idea of ‘successful aging’ is clearly one that is highly contrary when conceived as an ideal for those with this intractable condition.

So what can be done to assist the aging adult with osteoarthritis to maximize their overall well-being, while minimizing their disability in an effort to still attain a ‘successful aging’ state of being? Clearly, the disease, a multi-dimensional one that includes psychological as well as physical symptoms is not reversible, and can readily spread from one joint to another, while progressively degenerating processes proceed unhindered. To favorably alter the potential downward spiral, and ensure the goal of ‘successful aging’, or ‘healthy aging’, research shows this is feasible in light of what we do know, even though this requires very careful assessments, and interventions that are not only carefully construed, but are carefully tailored and titrated.

Fortunately, as with healthy adults, an extensive array of related research testifies to the enormous benefits of exercise adoption and muscle conditioning in this context, which is consistent with the idea that the health condition is more likely to occur in the presence of weak muscles or muscle pathology than not. As well, the finding that those who exercise, are more likely fewer weight issues, and are better off than those with high body weights speaks to an important role for both exercise and weight control in efforts to attain a successful health outcome, despite the disease. Other salient strategies related to joint protection efforts, such as the avoidance of undue joint stressors, vigorous exercises, and excess use of opioid narcotics, among other approaches will help foster the ability to pursue health goals more readily than not. As well, the use of heat and cold applications-as required, along with selected oral and topical medications, stress reduction efforts, ergonomic adaptations of the home and workplace, adaptive devices, and social support are found to help assist the patient with this condition to substantively raise their life quality, and to possible attenuate the disease symptoms, as well the risk of injury and comorbid health conditions such as diabetes. As with all attempts to foster ‘successful aging’, early intervention in childhood and adolescence is indicated, even though osteoarthritis is often considered an age-associated disease.

In sum, disabling and debilitating osteoarthritis, the most common joint disease affecting older populations, may not be inevitable, in all cases, and even when present, its severity and extent can be attenuated and may be amenable to amelioration if careful evaluations followed by carefully construed and timely treatment strategies are forthcoming and sustained where necessary. Some of the non-operative approaches for helping the osteoarthritis sufferer to maximize their health outcomes, may yet promote feelings of ‘success’ and control over their condition in the face of a very demoralizing disease state.

It is also reasonable to suggest that providers who adopt realistic outcome goals for effective rheumatic pain management for their patients, and help them to moderate any erroneous constraint beliefs [

25], and to convey this clearly to the patient will help them to avoid unrealistic expectations, as well as excess pessimism, for example, believing joint surgery will be restorative or painfree, or that opioids that relieve pain are safe, or believing their condition is not amenable to intervention. In addition, even though pain—the symptom of most concern to patients is unlikely to be completely abolished, regardless of intervention, helping patients to understand the key determinants of pain, and what to avoid, or act on is very key to success. As well, to foster adherence behaviors, barriers to effective pain management from both the patient and the healthcare professional perspectives should be minimized. In this respect, acceptance therapy, where the patient is encouraged to accept their situation, but not to lose sight of their goals, appears very worthy of consideration and application. Joining a support group or acting as an advocate for others or journaling have been shown to advance well-being despite the presence of disability, and regardless of age.

It is also reasonable to suggest that providers who adopt realistic outcome goals for effective rheumatic pain management for their patients, and help them to moderate any erroneous constraint beliefs [

25], and to convey this clearly to the patient will help them to avoid unrealistic expectations, as well as excess pessimism, for example, believing joint surgery will be restorative or painfree, or that opioids that relieve pain are safe, or believing their condition is not amenable to intervention. In addition, even though pain-the symptom of most concern to patients is unlikely to be completely abolished, regardless of intervention, helping patients to understand the key determinants of pain, and what to avoid, or act on is very key to success. As well, to foster adherence behaviors, barriers to effective pain management from both the patient and the healthcare professional perspectives should be minimized. In this respect, acceptance therapy, where the patient is encouraged to accept their situation, but not to lose sight of their goals, appears very worthy of consideration and application. Joining a support group or acting as an advocate for others or journaling have been shown to advance well-being despite the presence of disability, and regardless of age.

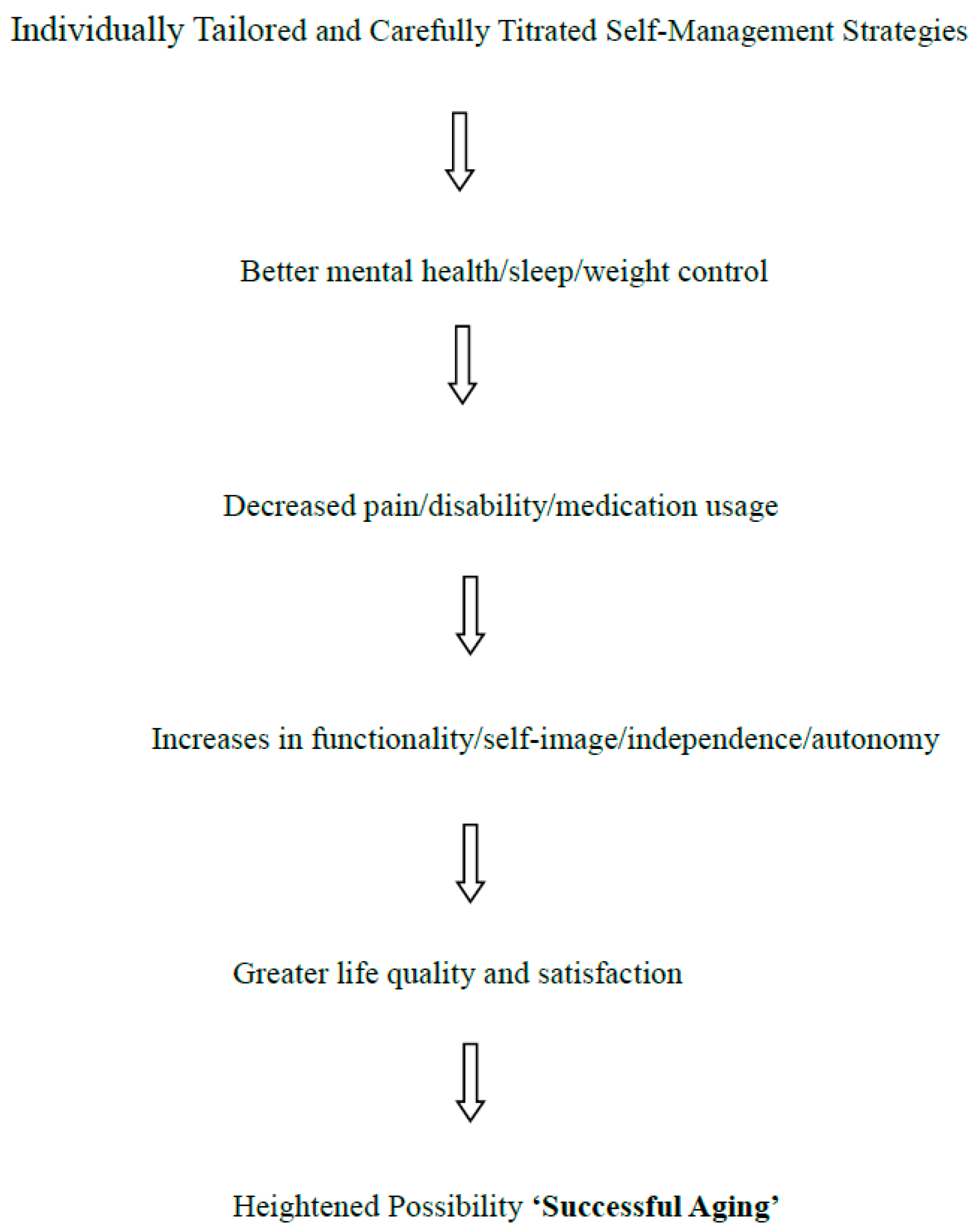

In short, as per

Figure 1 shown below, it is highly possible for an older adult with osteoarthritis, to age ‘successfully’ in our view, especially if they try to proactively contribute to their own wellbeing on a consistent basis, in conjunction with their provider’s recommendations, despite an associated array of cognitive and physical challenges. This ability to manage their health condition is not a given though, and may depend not only on the degree of presiding impairment, but on other intrinsic factors such as health beliefs, motivation and ability to comply with their providers’ recommendations, and extrinsically on the degree to which providers are knowledgeable and accessible, program attributes are tailored and clearly imparted, and the degree of societal or family support. More direct interventions include the use of supplements, topical gels, maintaining a healthy weight and blood pressure, plus home improvements and worksite adaptations to minimize joint and overall stress. In the meantime, an acceptance of a broader definition of ‘successful aging’ is fundamental in this regard in this author’s view, along with the understanding that the disease affects the whole body, not just a single joint, including the neurological, structural, and cardiovascular components of the body, and their relationship to physical, mental, emotional, and social wellbeing, and that it is not inevitable or subject solely to deterioration.