Legacy and Emerging Organophosphate Esters (OPEs) in a Rural–Urban Transition Watershed: Spatiotemporal Distribution, Sources, and Toxicity Screening

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

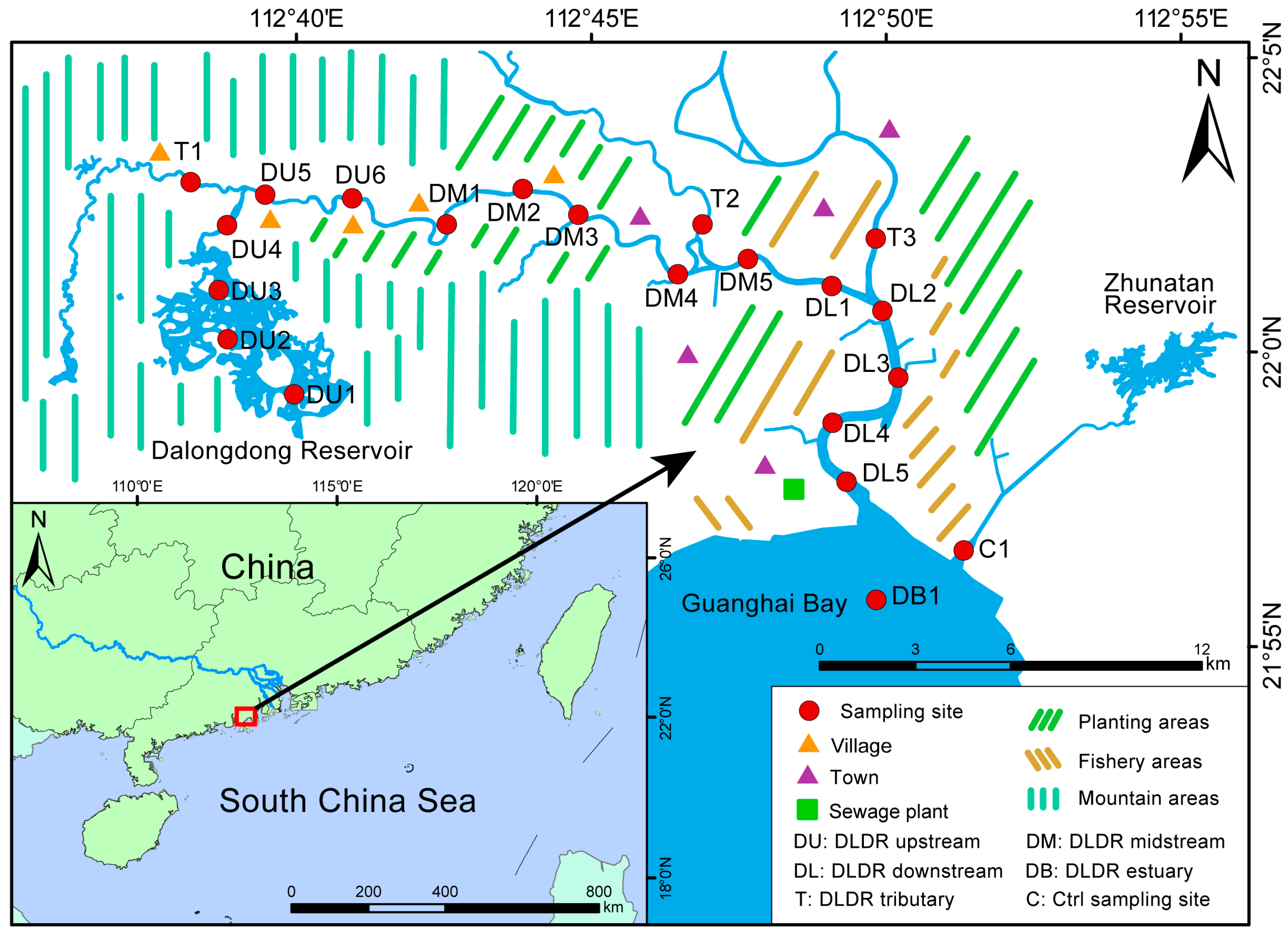

2.1. Study Area and Sample Collection

2.2. Chemicals and Reagents

2.3. Non-Target Screening and Identification of OPEs

2.4. Quantifying the OPEs in the Water and Sediment from the DLDR

2.5. Quality Assurance and Quality Control (QA/QC)

2.6. Partitioning Coefficients of OPEs

2.7. C. elegans High-Throughput Phenotypic Screening of OPEs and Toxicological Prioritization Index Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Contamination Profiles of OPEs

3.2. Spatiotemporal Distribution of OPEs

3.2.1. Distribution of Dry and Wet Seasons

3.2.2. Spatial Distribution Along the Rural–Urban Gradient

3.3. Partitioning of OPEs Between Water and Sediment

3.4. High-Throughput Phenotypic Toxicity Screening and ToxPi Toxicity Assessment of OPEs in the DLDR Watershed

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Greaves, A.K.; Letcher, R.J. A Review of Organophosphate Esters in the Environment from Biological Effects to Distribution and Fate. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2016, 98, 2–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, M. Flame Retardant Chemicals: Technologies and Global Markets; BCC Research: Boston, MA, USA, 2022; Available online: https://www.bccresearch.com/market-research/chemicals/flame-retardant-chemicals-report-chm014m.html (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Dou, M.; Wang, L. A review on organophosphate esters: Physiochemical properties, applications, and toxicities as well as occurrence and human exposure in dust environment. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 325, 116601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Meng, Y.; Liu, S.; Wei, L.; Huang, Q.H. Insights into organophosphate esters (OPEs) in aquatic ecosystems: Occurrence, environmental behavior, and ecological risk. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 54, 641–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ECHA, Substance Infocard-Tri [2-chloro-1-(chloromethyl)ethyl] Phosphate. 2023. Available online: https://echa.europa.eu/brief-profile/-/briefprofile/100.033.767 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- USEPA. TSCA Work Plan Chemical Problem Formuation and Initial Assessment. 2015. Available online: https://nepis.epa.gov/Exe/ZyPDF.cgi/P100N3WF.PDF?Dockey=P100N3WF.PDF (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; Bi, R.; Ye, L.; Su, G. High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry Screening of Emerging Organophosphate Esters (OPEs) in Wild Fish: Occurrence, Species-Specific Difference, and Tissue-Specific Distribution. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 302–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, F.; Jiang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Li, M.; Ye, C.; Wang, W.; Ge, M.; Chen, C.; Zhao, J. The Key Role of Sulfate in the Photochemical Renoxification on Real PM(2.5). Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 3121–3128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, L.; Li, J.; Gong, S.; Herczegh, S.M.; Zhang, Q.; Letcher, R.J.; Su, G. Established and emerging organophosphate esters (OPEs) and the expansion of an environmental contamination issue: A review and future directions. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 459, 132095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Xie, Z.Y.; Mi, W.Y.; Lai, S.C.; Tian, C.G.; Emeis, K.C.; Ebinghaus, R. Organophosphate Esters in Air, Snow, and Seawater in the North Atlantic and the Arctic. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 6887–6896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.Q.; Zhang, G.X.; Chen, C.C.; Luo, M.; Xu, H.Z.; Chen, D.F.; Liu, R.L.; Li, Y.M.; Zhang, Q.H.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Tracing Organophosphate Ester Pollutants in Hadal Trenches-Distribution, Possible Origins, and Transport Mechanisms. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 4392–4403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, S.; Chen, X.; Zhou, Y. Critical review on organophosphate esters in water environment: Occurrence, health hazards and removal technologies. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 343, 123218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Li, J.; Meng, W.; Su, G. A critical review on organophosphate esters in drinking water: Analysis, occurrence, sources, and human health risk assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 913, 169663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Qian, J.; Zhang, B.; Chen, L.; Wei, S.; Pan, B. Unveiling the Occurrence and Potential Ecological Risks of Organophosphate Esters in Municipal Wastewater Treatment Plants across China. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 1907–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lao, Z.; Li, H.; Liao, Z.; Liu, Y.; Ying, G.; Song, A.; Liu, M.; Liu, H.; Hu, L. Spatiotemporal transitions of organophosphate esters (OPEs) and brominated flame retardants (BFRs) in sediments from the Pearl River Delta, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 855, 158807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paun, I.; Pirvu, F.; Chiriac, F.L.; Iancu, V.I.; Pascu, L.F. Organophosphate flame retardants in Romania coastline: Occurrence, faith and environmental risk. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2024, 208, 116982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gbadamosi, M.R.; Al-Omran, L.S.; Abdallah, M.A.; Harrad, S. Concentrations of organophosphate esters in drinking water from the United Kingdom: Implications for human exposure. Emerg. Contam. 2023, 9, 100203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardila, P.A.R.; Alonso, R.Á.; Cabrera, F.Á.; Valsero, J.J.D.; García, R.M.; Cosío, E.L.; Oceguera, V.L.; DelValls, A. Assessment and review of heavy metals pollution in sediments of the Mediterranean Sea. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardila, P.A.R.; Alonso, R.Á.; Valsero, J.J.D.; García, R.M.; Cabrera, F.Á.; Cosío, E.L.; Laforet, S.D. Assessment of heavy metal pollution in marine sediments from southwest of Mallorca island, Spain. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 16852–16866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Y.; Zhao, J.; Li, Z.; Zhu, L. Distribution, traceability, and risk assessment of organophosphate flame retardants in agricultural soils along the Yangtze River Delta in China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2024, 31, 41013–41024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.X.; Chen, H.Y.; Ma, J.; Liu, Q.Y.; Qu, Y.J.; Zhao, W.H. A critical review on sources and environmental behavior of organophosphorus flame retardants in the soil: Current knowledge and future perspectives. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 452, 131161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Z.; Deng, W.; Hu, L.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, Y. Legacy and emerging organophosphate flame retardants (OPFRs) in water and sediment from the Pearl River Delta to the adjacent coastal waters of the South China Sea: Spatioseasonal variations, flux estimation and ecological risk. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 367, 125633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, K.; Shi, F.; Liu, J. Occurrence and distribution of oligomeric organophosphorus flame retardants in different treatment stages of a sewage treatment plant. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 232, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, R.; Xing, L. Organophosphate esters in rural wastewater along the Yangtze river Basin: Occurrence, removal efficiency and environmental implications. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 345, 118830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queirós, L.; Pereira, J.L.; Gonçalves, F.J.M.; Pacheco, M.; Aschner, M.; Pereira, P. Caenorhabditis elegans as a tool for environmental risk assessment: Emerging and promising applications for a “nobelized worm”. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 2019, 49, 411–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yang, Q.Q.; Wang, L.; Song, C.X.; Chen, L.F.; Zhang, J.; Liang, Y. Using Caenorhabditis elegans to assess the ecological health risks of heavy metals in soil and sediments around Dabaoshan Mine, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 16332–16345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pu, J.; Li, J.; Zhang, T.; Martin, J.B.; Yuan, D. Varying thermal structure controls the dynamics of CO2 emissions from a subtropical reservoir, south China. Water Res. 2020, 178, 115831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Veen, I.; de Boer, J. Phosphorus flame retardants: Properties, production, environmental occurrence, toxicity and analysis. Chemosphere 2012, 88, 1119–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Z.H.; Cao, Y.T.; Li, D.; Wu, C.G.; Wu, K.H.; Song, Y.Y.; Huang, Z.J.; Luan, H.M.; Meng, X.J.; Yang, Z.; et al. Nontarget Analysis of Legacy and Emerging PFAS in a Lithium-Ion Power Battery Recycling Park and Their Possible Toxicity Measured Using High-Throughput Phenotype Screening. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 14530–14540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner, S. The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 1974, 77, 71–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Zhang, S.-H.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, B.; Pu, Y.-Q.; Zhao, X.; Li, H.; Song, N.-H.; Guo, R.-X. Occurrence and Risk Assessment of Organophosphate Esters in Source Water of the Nanjing Section of the Yangtze River. Huan Jing Ke Xue Huanjing Kexue 2020, 41, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, H.; Mi, W.; Li, X.; Wang, S.; Yan, J.; Zhang, G. Organophosphate ester in surface water of the Pearl River and South China Sea, China: Spatial variations and ecological risks. Chemosphere 2024, 361, 142559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, M.S.; Lin, C.Y.; Wu, T.T.; Xin, M.; Gu, X.; Lu, S.; Cao, Y.X.; Wang, B.D.; Ouyang, W.; Liu, X.T.; et al. Occurrence, spatiotemporal distribution, and ecological risks of organophosphate esters in the water of the Yellow River to the Laizhou Bay, Bohai Sea. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 787, 147528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.S.; Li, H.R.; Lao, Z.L.; Ma, S.T.; Liao, Z.C.; Song, A.M.; Liu, M.Y.; Liu, Y.S.; Ying, G.G. Organophosphate esters (OPEs) in a heavily polluted river in South China: Occurrence, spatiotemporal trends, sources, and phase distribution. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 336, 122492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, M.J.; Lu, J.F.; Wei, S.Q. Organophosphate esters in biota, water, and air from an agricultural area of Chongqing, western China: Concentrations, composition profiles, partition and human exposure. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 244, 388–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, D.; Wang, J.; Xia, H.; Zhang, Y.; Bao, F.; Li, M.; Chen, C.; Zhao, J. Enhanced Photochemical Volatile Organic Compounds Release from Fatty Acids by Surface-Enriched Fe(III). Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 13448–13457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, J.Y.; Feng, S.; Hao, Y.D.; Lin, J.N.; Zhang, B. Pollution characteristics and risk assessment of organophosphate esters in aquaculture farms and natural water bodies adjacent to the Huanghe River delta. J. Oceanol. Limnol. 2023, 41, 251–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, M.S.; Lin, C.Y.; Xin, M.; Gu, X.; Lu, S.; Wang, B.D.; Ouyang, W.; Liu, X.T.; He, M.C. Organophosphate esters in surface waters of Shandong Peninsula in eastern China: Levels, profile, source, spatial distribution, and partitioning. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 297, 118792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.M.; Dou, W.K.; Zhang, X.Q.; Sun, A.L.; Chen, J.; Shi, X.Z. Organophosphate esters in the mariculture ecosystem: Environmental occurrence and risk assessments. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 436, 129219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Wei, C.S.; Zhang, R.J.; Zeng, W.B.; Han, M.W.; Kang, Y.R.; Zhang, Z.E.; Wang, R.X.; Yu, K.F.; Wang, Y.H. Occurrence, distribution, source identification, and risk assessment of organophosphate esters in the coastal waters of Beibu Gulf, South China Sea: Impacts of riverine discharge and fishery. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 436, 129214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.H.; Wang, Y.; Kannan, K. Occurrence, distribution and human exposure to 20 organophosphate esters in air, soil, pine needles, river water, and dust samples collected around an airport in New York state, United States. Environ. Int. 2019, 131, 105054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, W.K.; Zhang, Z.M.; Huang, W.; Wang, X.N.; Zhang, R.R.; Wu, Y.Y.; Sun, A.L.; Shi, X.Z.; Chen, J. Contaminant occurrence, spatiotemporal variation, and ecological risk of organophosphorus flame retardants (OPFRs) in Hangzhou Bay and east China sea ecosystem. Chemosphere 2022, 303, 135032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, B. Levels and distribution of chlorinated pesticide residues in water and sediments of Tarkwa Bay, Lagos Lagoon. J. Res. Environ. Sci. Toxicol. 2013, 2, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, F.Y.; Tan, Q.; Qin, H.G.; Wang, D.Q.; Cai, Y.P.; Zhang, J. Sequestration and export of microplastics in urban river sediments. Environ. Int. 2023, 181, 108265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwanen, C.A.; Müller, J.; Schulte, P.; Schwarzbauer, J. Distribution, remobilization and accumulation of organic contaminants by flood events in a meso-scaled catchment system. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2023, 35, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.W.; Yang, C.; Liu, M.Y.; Zhao, W.Y.; Li, Y.X.; Meng, X.Z.; Cai, M.H. Occurrence of organophosphate esters in surface water and sediment in drinking water source of Xiangjiang River, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 781, 146734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantelaki, I.; Voutsa, D. Occurrence and removal of organophosphate esters in municipal wastewater treatment plants in Thessaloniki, Greece. Environ. Res. 2022, 214, 113908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.P.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Mai, L.; Liu, L.Y.; Bao, L.J.; Zeng, E.Y. Selected antibiotics and current-use pesticides in riverine runoff of an urbanized river system in association with anthropogenic stresses. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 739, 140004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onoja, S.; Abdallah, M.A.E.; Harrad, S. Concentrations, spatial and seasonal variations of Organophosphate esters in UK freshwater Sediment. Emerg. Contam. 2023, 9, 100243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.L.; Wan, Y.J.; Wang, Y.; He, Z.Y.; Xu, S.Q.; Xia, W. Occurrence, spatial variation, seasonal difference, and ecological risk assessment of organophosphate esters in the Yangtze River, China: From the upper to lower reaches. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 851, 158021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, G.L.; Li, D.Q.; Zhuo, M.N.; Liao, Y.S.; Xie, Z.Y.; Guo, T.L.; Li, J.J.; Zhang, S.Y.; Liang, Z.Q. Organophosphorus flame retardants and plasticizers: Sources, occurrence, toxicity and human exposure. Environ. Pollut. 2015, 196, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, W.J.; Cui, Y.N.; Li, R.X.; Yang, R.Y.; Li, Y.; Zhu, L.Y. Distribution and sources of ordinary monomeric and emerging oligomeric organophosphorus flame retardants in Haihe Basin, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 785, 147274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, M.S.; Lin, C.Y.; Li, Y.; Hao, X.; Wang, A.H.; He, M.C.; Liu, X.T.; Ouyang, W. Distribution, partitioning, and health risk assessment of organophosphate esters in a major tributary of middle Yangtze River using Monte Carlo simulation. Water Res. 2022, 219, 118559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noyes, P.D.; Haggard, D.E.; Gonnerman, G.D.; Tanguay, R.L. Advanced Morphological—Behavioral Test Platform Reveals Neurodevelopmental Defects in Embryonic Zebrafish Exposed to Comprehensive Suite of Halogenated and Organophosphate Flame Retardants. Toxicol. Sci. 2015, 145, 177–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Q.; Yang, H.; Zheng, Y.; Zheng, N.; Lei, L.; Li, X.; Ding, W. Neurotoxicity of an emerging organophosphorus flame retardant, resorcinol bis(diphenyl phosphate), in zebrafish larvae. Chemosphere 2023, 334, 138944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, N.; Lai, C.; Xu, F.; Huang, D.; Zhang, M.; Zhou, X.; Xu, M.; Li, Y.; Li, L.; Liu, S.; et al. A review of polybrominated diphenyl ethers and novel brominated flame retardants in Chinese aquatic environment: Source, occurrence, distribution, and ecological risk assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 904, 166180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Guo, S.; Deng, W.; Zhan, X.; Li, D.; Fei Koo, I.Y.; Zhang, N.; Chen, H.; Wang, Q.; Liu, Q.; Wang, X.; et al. Legacy and Emerging Organophosphate Esters (OPEs) in a Rural–Urban Transition Watershed: Spatiotemporal Distribution, Sources, and Toxicity Screening. Toxics 2026, 14, 147. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14020147

Guo S, Deng W, Zhan X, Li D, Fei Koo IY, Zhang N, Chen H, Wang Q, Liu Q, Wang X, et al. Legacy and Emerging Organophosphate Esters (OPEs) in a Rural–Urban Transition Watershed: Spatiotemporal Distribution, Sources, and Toxicity Screening. Toxics. 2026; 14(2):147. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14020147

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuo, Shulin, Weicong Deng, Xuan Zhan, Dan Li, Ivy Yik Fei Koo, Naisheng Zhang, Hongliang Chen, Qiabin Wang, Qin Liu, Xutao Wang, and et al. 2026. "Legacy and Emerging Organophosphate Esters (OPEs) in a Rural–Urban Transition Watershed: Spatiotemporal Distribution, Sources, and Toxicity Screening" Toxics 14, no. 2: 147. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14020147

APA StyleGuo, S., Deng, W., Zhan, X., Li, D., Fei Koo, I. Y., Zhang, N., Chen, H., Wang, Q., Liu, Q., Wang, X., Yu, Y., Qi, Z., & Zhang, Y. (2026). Legacy and Emerging Organophosphate Esters (OPEs) in a Rural–Urban Transition Watershed: Spatiotemporal Distribution, Sources, and Toxicity Screening. Toxics, 14(2), 147. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14020147