Pyrrhotite Facilitates Growth and Cr Accumulation in Leersia hexandra Swartz for Effective Cr(VI) Removal in Constructed Wetlands

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

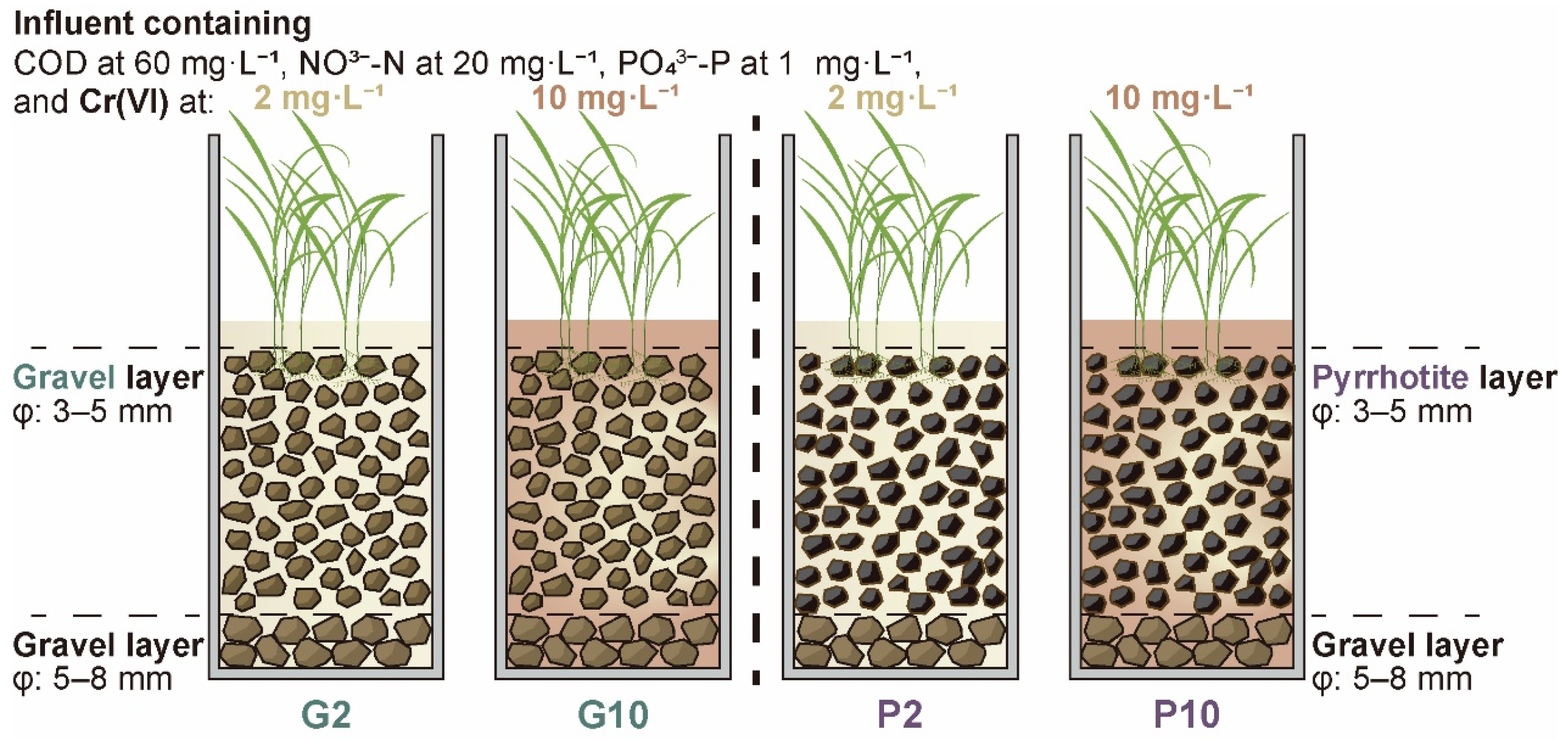

2.1. Microcosm Setup and Operation

2.2. Water Sampling and Analyses

2.3. Plant Sampling and Analyses

2.4. Microbial Sampling and Analyses

2.5. Statistical Analyses

3. Results and Discussion

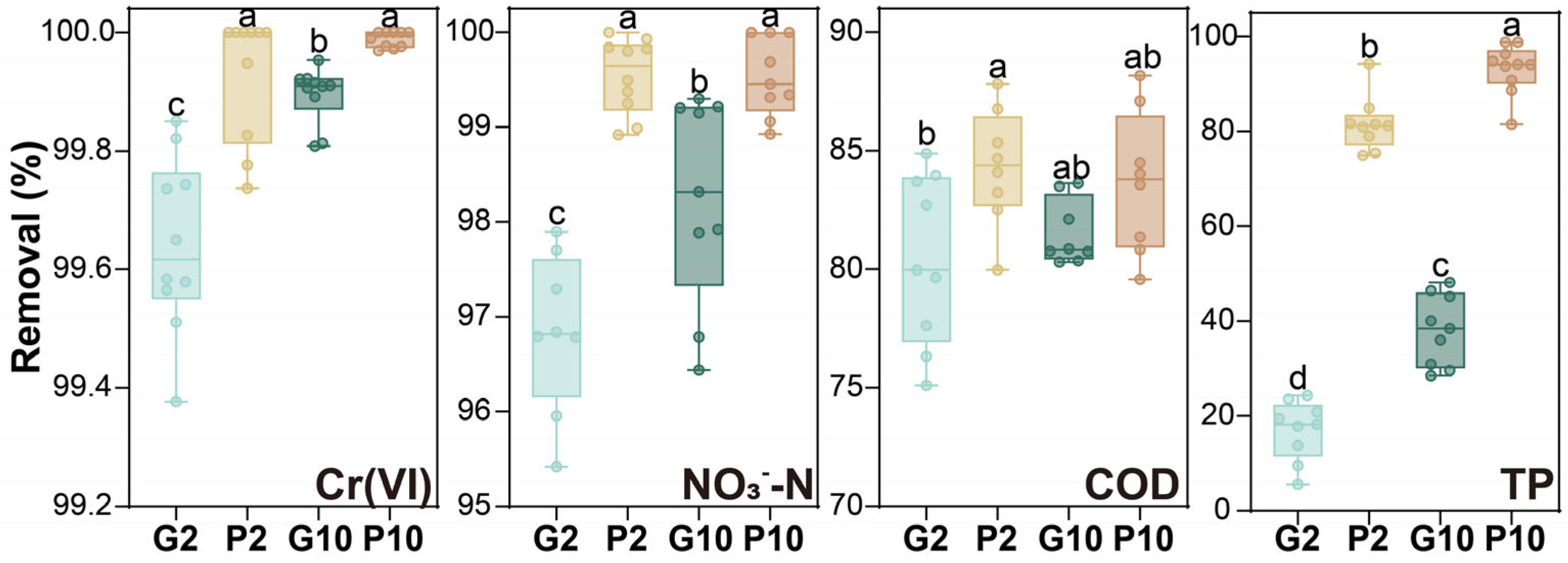

3.1. Overall Treatment Performance

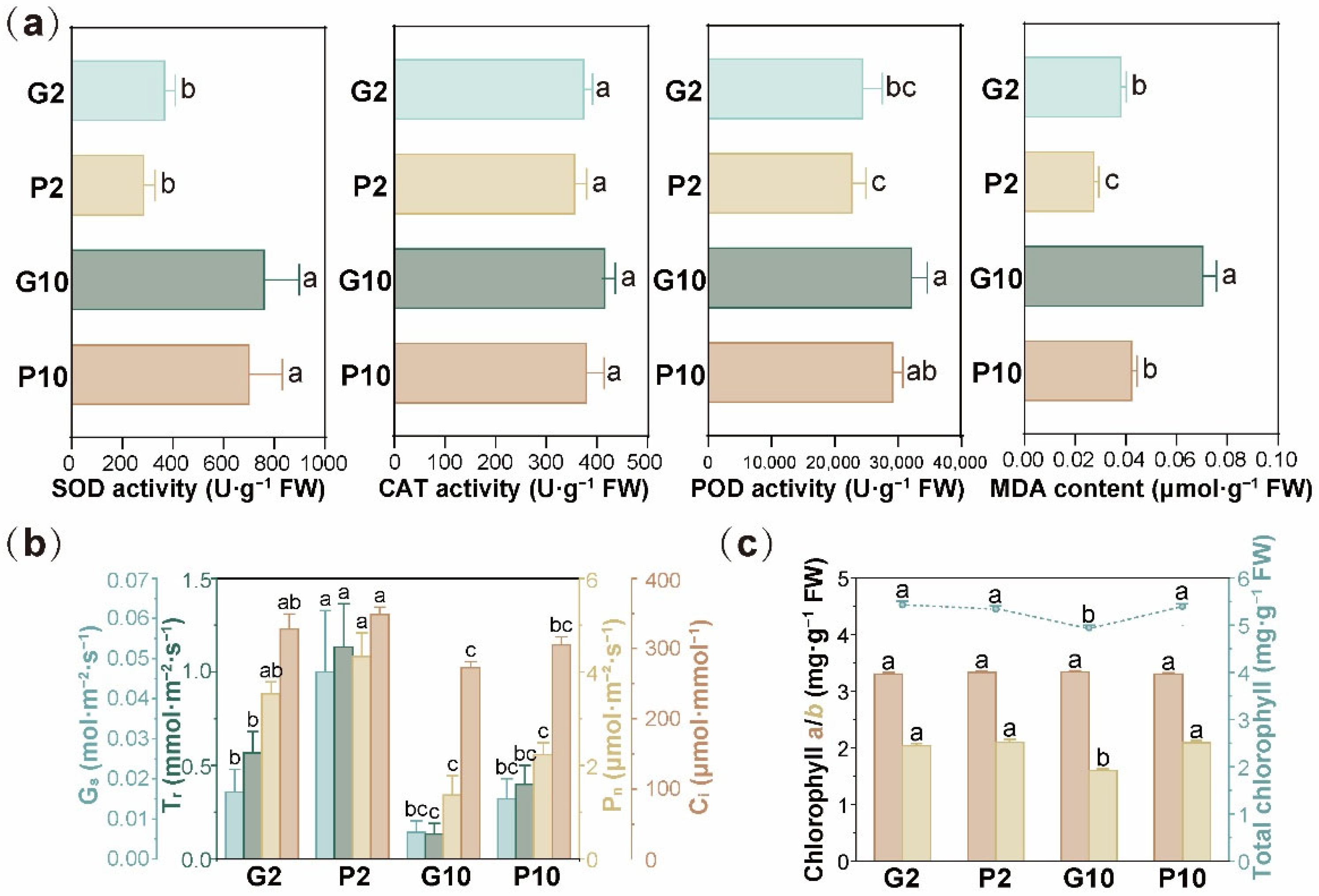

3.2. Effect of Pyrrhotite on Physiology of L. hexandra

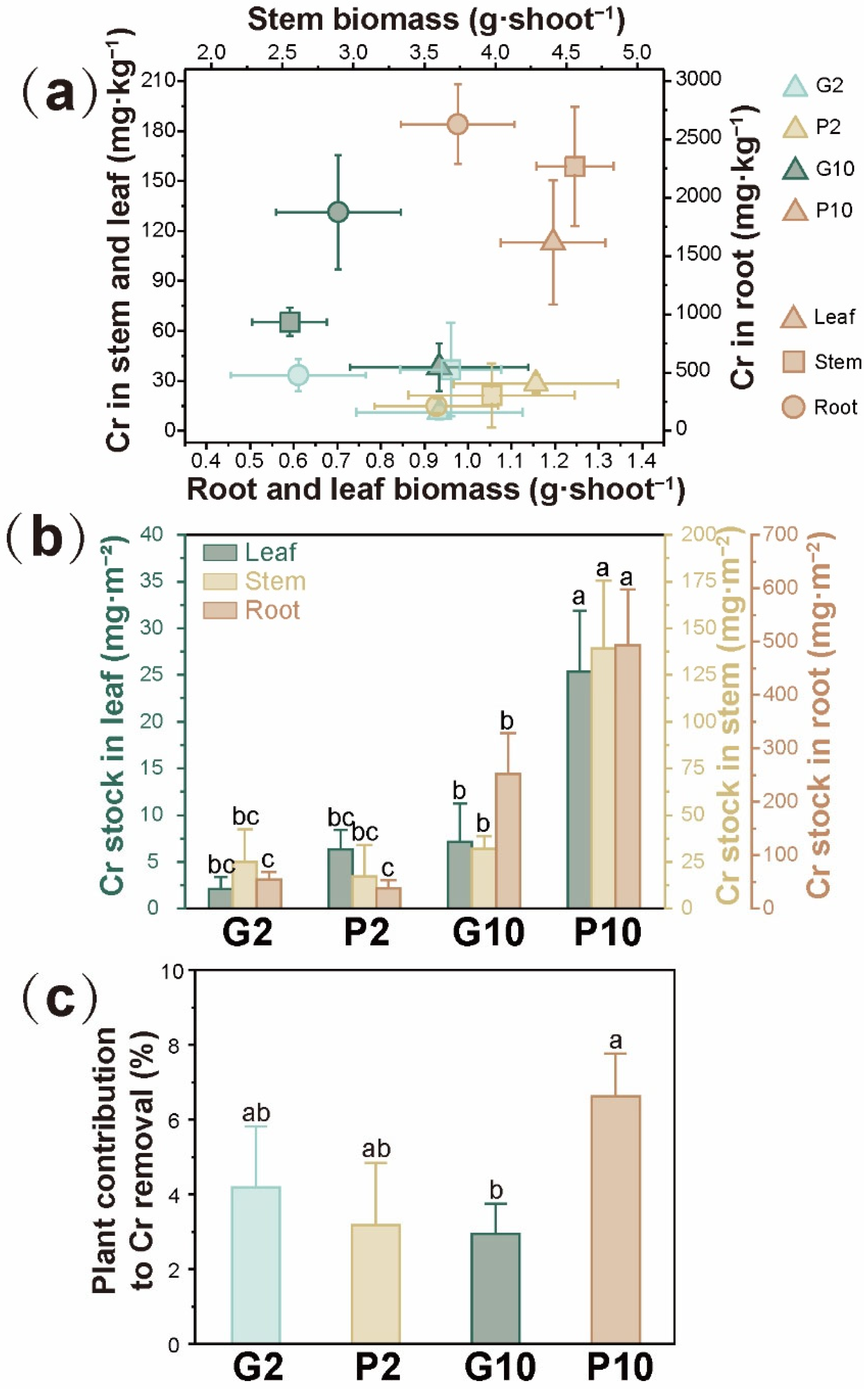

3.3. Effect of Pyrrhotite on Growth and Cr Accumulation in L. hexandra

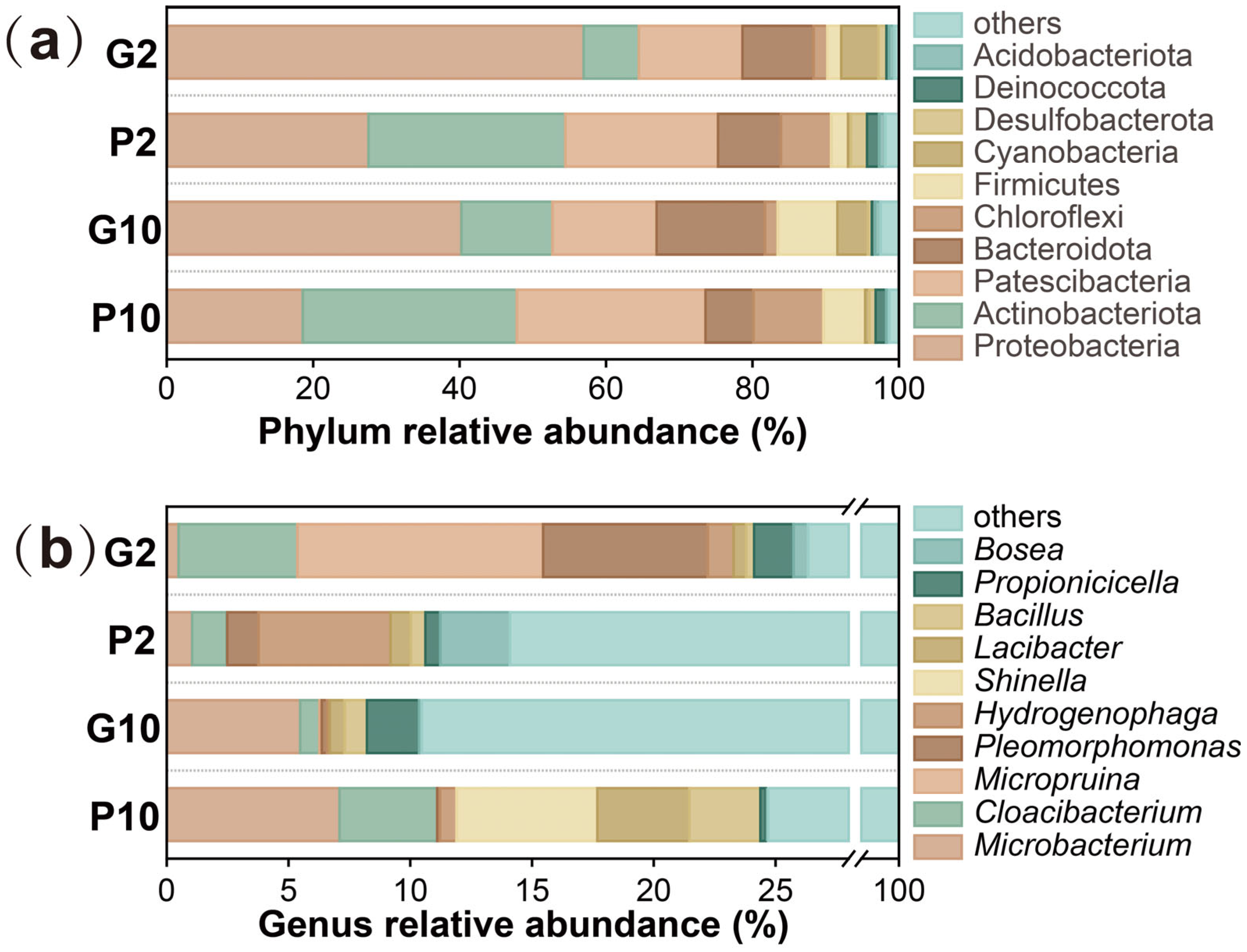

3.4. Effect of Pyrrhotite on Microbial Community Structure

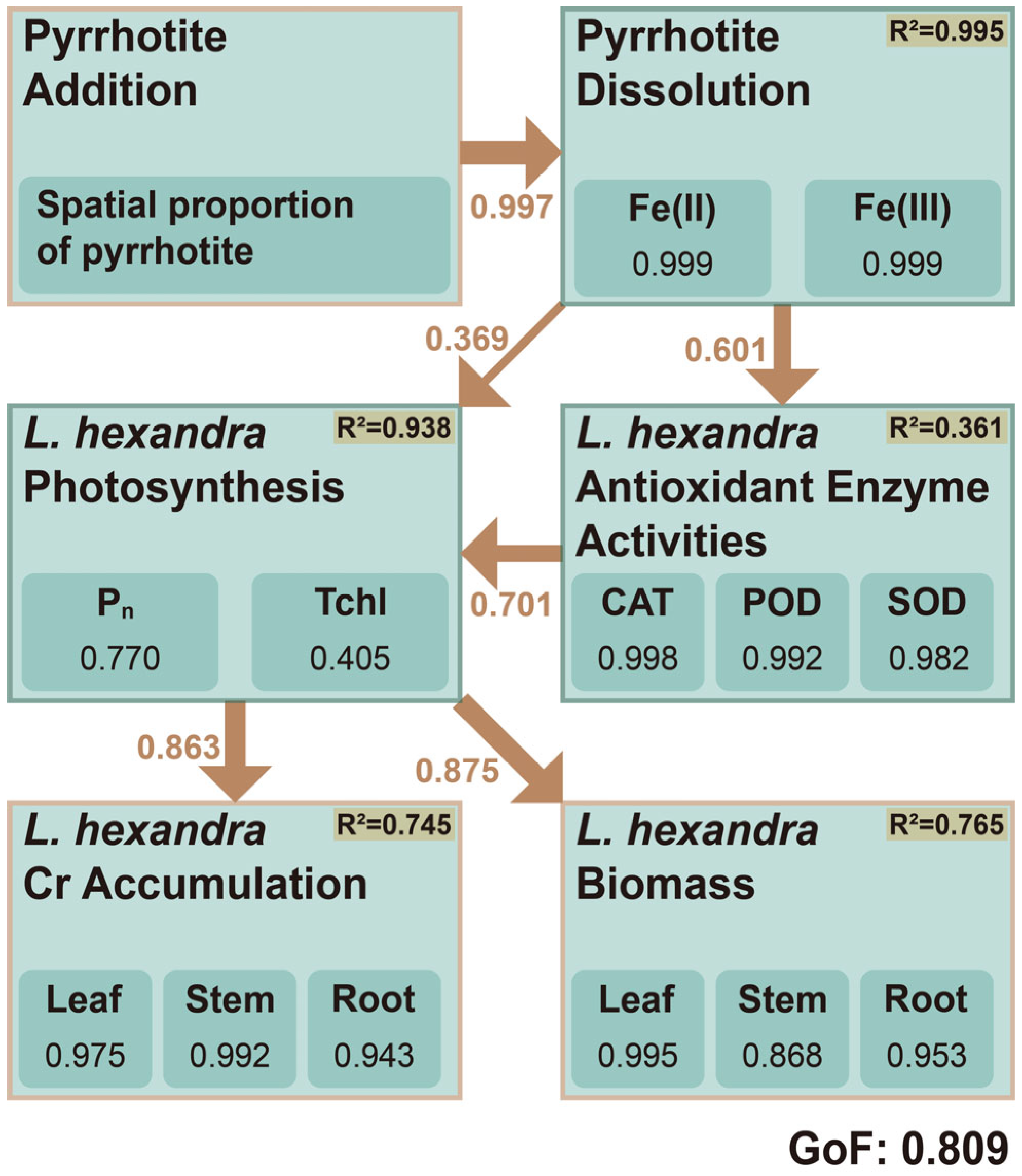

3.5. Facilitating Mechanism of Pyrrhotite in L. hexandra Application

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lin, Y.; Lin, H.; Jiang, M.; Lv, J.; Zhang, X.; Yan, J. Multiple electron transfer processes facilitate the simultaneous removal of NO3−-N and Cr(VI) in a pyrrhotite-based mixotrophic constructed wetland. J. Water Process Eng. 2025, 72, 107588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, M.; Lin, H.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, X.; Yan, J. Elemental sulfur facilitates co-metabolism of Cr(VI) and nitrate by autotrophic denitrifiers in constructed wetlands. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 492, 138153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.; Wang, R.; Yan, P.; Wu, S.; Chen, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Cheng, C.; Hu, Z.; Zhuang, L.; Guo, Z.; et al. Constructed wetlands for pollution control. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2023, 4, 218–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Q.; Guo, W.; Sun, R.; Qin, M.; Zhao, Z.; Du, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, C.; Wang, X.; Zhang, R.; et al. Enhancement of chromium removal and energy production simultaneously using iron scrap as anodic filling material with pyrite-based constructed wetland-microbial fuel cell. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 106630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, K.; Zhang, J.; Deng, Z.; Barnie, S.; Chang, J.; Zou, Y.; Guan, X.; Liu, F.; Chen, H. Natural attenuation mechanism of hexavalent chromium in a wetland: Zoning characteristics of abiotic and biotic effects. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 287, 117639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vymazal, J.; Březinová, T. Accumulation of heavy metals in aboveground biomass of Phragmites australis in horizontal flow constructed wetlands for wastewater treatment: A review. Chem. Eng. J. 2016, 290, 232–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shweta, S.; Saswati, C. Performance of organic substrate amended constructed wetland treating acid mine drainage (AMD) of North-Eastern India. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 397, 122719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustapha, H.I.; van Bruggen, J.J.A.; Lens, L.P.N. Fate of heavy metals in vertical subsurface flow constructed wetlands treating secondary treated petroleum refinery wastewater in Kaduna, Nigeria. Int. J. Phytoremediat. 2018, 20, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesage, E.; Rousseau, D.P.L.; Meers, E.; Tack, F.M.G.; De Pauw, N. Accumulation of metals in a horizontal subsurface flow constructed wetland treating domestic wastewater in Flanders, Belgium. Sci. Total Environ. 2007, 380, 102–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fibbi, D.; Doumett, S.; Lepri, L.; Checchini, L.; Gonnelli, C.; Coppini, E.; Del Bubba, M. Distribution and mass balance of hexavalent and trivalent chromium in a subsurface, horizontal flow (SF-h) constructed wetland operating as post-treatment of textile wastewater for water reuse. J. Hazard. Mater. 2012, 199, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, A.; Bellaloui, N.; Pilipovic, A.; Perez, E.; Maddox-Mandolini, M.; Fuente, H.D.L. Current Assessment and Future Perspectives on Phytoremediation of Heavy Metals. Plants 2025, 14, 2847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malaviya, P.; Singh, A.; Anderson, T.A. Aquatic phytoremediation strategies for chromium removal. Rev. Environ. Sci. Biotechnol. 2020, 19, 897–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Jiang, P.; Zhang, X.; Sunahara, G.I.; Liu, J.; Yu, G. Physiological and biochemical responses of Leersia hexandra Swartz to nickel stress: Insights into antioxidant defense mechanisms and metal detoxification strategies. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 466, 133578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, J.; Huang, H.; Chen, J.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, D. Chromium accumulation by the hyperaccumulator plant Leersia hexandra Swartz. Chemosphere 2007, 67, 1138–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Zhao, J.; Wang, J.; Yang, L.; Xu, Y.; Yu, G.; Bai, S.; Liu, L. Enhancement of iron-loaded sludge biochar on Cr accumulation in Leersia hexandra swartz: Hydroponic test. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 349, 119389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Gao, B.; Guo, Y.; Yu, Q.; Hu, M.; Zhang, X. Adding carbon sources to the substrates enhances Cr and Ni removal and mitigates greenhouse gas emissions in constructed wetlands. Environ. Res. 2024, 252, 118940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, W.; Liu, R.; Zhang, F.; Shi, Y.; Wang, J.; Tang, Q.; Yang, Y.; Man, Y.; et al. Plants boost pyrrhotite-driven nitrogen removal in constructed wetlands. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 367, 128240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Wei, D.; Hu, J.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Z.; Li, A.; Li, R. Glyphosate and nutrients removal from simulated agricultural runoff in a pilot pyrrhotite constructed wetland. Water Res. 2020, 168, 115154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tombuloglu, H.; Slimani, Y.; Tombuloglu, G.; Alshammari, T.; Almessiere, M.; Korkmaz, A.D.; Baykal, A.; Samia, A.C.S. Engineered magnetic nanoparticles enhance chlorophyll content and growth of barley through the induction of photosystem genes. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 34311–34321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Liu, S.; Bi, M.; Yang, X.; Deng, R.; Chen, Y. Aging behavior of microplastics affected DOM in riparian sediments: From the characteristics to bioavailability. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 431, 128522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, L.; Liu, H.; Kong, Q.; Li, M.; Wu, S.; Wu, H. Interactions of high-rate nitrate reduction and heavy metal mitigation in iron-carbon-based constructed wetlands for purifying contaminated groundwater. Water Res. 2020, 169, 115285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bu, Y.; Song, M.; Huang, G.; Chen, C.; Li, R. High-rate nitrogen and phosphorus removal in a sulfur and pyrrhotite modified foam concrete constructed wetland. Bioresour. Technol. 2025, 419, 132008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, Z.; Wei, D.; Zhang, J.; Hu, J.; Liu, Z.; Li, R. Natural pyrite to enhance simultaneous long-term nitrogen and phosphorus removal in constructed wetland: Three years of pilot study. Water Res. 2019, 148, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.; Zhang, X.; Jiang, P.; Liu, J.; You, S.; Lv, Y. Advances in heavy metals detoxification, tolerance, accumulation mechanisms, and properties enhancement of Leersia hexandra Swartz. J. Plant Interact. 2022, 17, 766–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Zhang, B.; Han, Y.; Guan, J.; Gao, H.; Guo, P. Role of reactive oxygen species (ROS) on biochar enhanced chromium phytoremediation in the soil-plant system: Exploration on detoxification mechanism. Environ. Int. 2025, 199, 109471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kour, J.; Bhardwaj, T.; Chouhan, R.; Singh, A.D.; Gandhi, S.G.; Bhardwaj, R.; Alsahli, A.A.; Ahmad, P. Phytomelatonin maintained chromium toxicity induced oxidative burst in Brassica juncea L. through improving antioxidant system and gene expression. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 356, 124256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Lin, Y.; Deng, Z.; Chen, M.; Yu, G.; Jiang, P.; Zhang, X.; Liu, J.; Yang, X. Transcriptome and metabolome analysis reveal key genes and metabolic pathway responses in Leersia hexandra Swartz under Cr and Ni co-stress. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 473, 134590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Ayyaz, A.; Farooq, M.A.; Zhang, K.; Chen, W.; Hannan, F.; Sun, Y.; Shahzad, K.; Ali, B.; Zhou, W. Silicon dioxide nanoparticles enhance plant growth, photosynthetic performance, and antioxidants defence machinery through suppressing chromium uptake in Brassica napus L. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 342, 123013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, R.; Ali, S.; Rizwan, M.; Dawood, M.; Farid, M.; Hussain, A.; Wijaya, L.; Alyemeni, M.N.; Ahmad, P. Hydrogen sulfide alleviates chromium stress on cauliflower by restricting its uptake and enhancing antioxidative system. Physiol. Plant 2020, 168, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Bakshi, P.; Chouhan, R.; Gandhi, S.G.; Kaur, R.; Sharma, A.; Bhardwaj, R.; Alsahli, A.A.; Ahmad, P. Combined application of earthworms and plant growth promoting rhizobacteria improve metal uptake, photosynthetic efficiency and modulate secondary metabolites levels under chromium metal toxicity in Brassica juncea L. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 482, 136489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.; Dhankher, O.P.; Tripathi, R.D.; Seth, C.S. Titanium dioxide nanoparticles potentially regulate the mechanism(s) for photosynthetic attributes, genotoxicity, antioxidants defense machinery, and phytochelatins synthesis in relation to hexavalent chromium toxicity in Helianthus annuus L. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 454, 131418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briat, J.-F.; Dubos, C.; Gaymard, F. Iron nutrition, biomass production, and plant product quality. Trends Plant Sci. 2015, 20, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, X.; Wen, J.; Mu, L.; Gao, Z.; Weng, J.; Li, X.; Hu, X. Regulation of arsenite toxicity in lettuce by pyrite and glutamic acid and the related mechanism. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 877, 162928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Ent, A.; Baker, A.J.M.; Reeves, R.D.; Joseph, P.A.; Henk, S. Hyperaccumulators of metal and metalloid trace elements: Facts and fiction. Plant Soil 2012, 362, 319–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Lin, Y.; Lin, H.; Yan, J. Constructed wetlands and hyperaccumulators for the removal of heavy metal and metalloids: A review. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 479, 135643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Tang, G.; You, S.; Jiang, P. Effect of External Aeration on Cr (VI) Reduction in the Leersia hexandra Swartz Constructed Wetland-Microbial Fuel Cell System. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 3309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Liu, Q.; Wu, G.; Zhao, S.; Li, Y.; You, S.; Huang, G. Removal and reduction mechanism of Cr (VI) in Leersia hexandra Swartz constructed wetland-microbial fuel cell coupling system. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 277, 116373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Li, G.; Shao, W.; Xu, J.; Wang, D. Variations in Uptake and Translocation of Copper, Chromium and Nickel Among Nineteen Wetland Plant Species. Pedosphere 2010, 20, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadlec, R.H.; Wallace, S. Treatment Wetlands; CRC Press: Boca Rato, FL, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H.; Yang, T.; Zhang, M.; Li, A.; Huang, D.; Xing, Z. Effect of HRT on nitrogen removal from low carbon source wastewater enhanced by slurry and its mechanism. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 477, 147159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhari, A.; Paul, D.; Thamke, V.; Bagade, A.; Bapat, V.A.; Kodam, K.M. Concurrent removal of reactive blue HERD dye and Cr(VI) by aerobic bacterial granules. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 367, 133075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Varma, A.; Prasad, R.; Porwal, S. Bioprospecting uncultivable microbial diversity in tannery effluent contaminated soil using shotgun sequencing and bio-reduction of chromium by indigenous chromate reductase genes. Environ. Res. 2022, 215, 114338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, S.; Wang, J.; Song, Q.; Zhang, W.; He, Q.; Song, J.; Ma, F. Comparison of performance and microbial communities in a bioelectrochemical system for simultaneous denitrification and chromium removal: Effects of pH. Process Biochem. 2018, 73, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, Q.; Yang, Z.; Jia, X.; Cabrera, J.; Ji, M. Bio-capture of Cr(VI) in a denitrification system: Electron competition, long-term performance, and microbial community evolution. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 432, 128697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koner, S.; Chen, J.; Hseu, Z.; Chang, E.; Chen, K.; Asif, A.; Hsu, B. An inclusive study to elucidation the heavy metals-derived ecological risk nexus with antibiotic resistome functional shape of niche microbial community and their carbon substrate utilization ability in serpentine soil. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 366, 121688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Liu, L.; Chang, Q.; Wang, H.; Yang, K. Biosorption of Cr(VI) ions from aqueous solutions by a newly isolated Bosea sp strain Zer-1 from soil samples of a refuse processing plant. Can. J. Microbiol. 2015, 61, 399–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Xiao, C.; Zheng, Y.; Li, Y.; Chi, R. Removal and potential mechanisms of Cr(VI) contamination in phosphate mining wasteland by isolated Bacillus megatherium PMW-03. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 322, 129062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Lu, S.; Yuan, T.; Zhang, F.; Wang, L.; Wang, P.; Wen, X.; Cui, L. Influences of dimethyl phthalate on bacterial community and enzyme activity in vertical flow constructed wetland. Water 2021, 13, 788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Y.; Yu, G.; Wang, J.; Zheng, D. Cadmium removal by constructed wetlands containing different substrates: Performance, microorganisms and mechanisms. Bioresour. Technol. 2024, 413, 131561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wetzels, M.; Odekerken-Schroder, G.; van Oppen, C. Using PLS path modeling for assessing hierarchical construct models: Guidelines and empirical illustration. MIS Q. 2009, 33, 177–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Luo, Y.; Nie, M.; Zheng, F.; Zhang, G.; Chen, Y. A comprehensive evaluation of biochar for enhancing nitrogen removal from secondary effluent in constructed wetlands. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 478, 147469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Su, C.; Zhang, Y.; Lai, S.; Han, S.; Zhang, X.; Zheng, J. Mineralogical characteristics of root iron plaque and its functional mechanism for regulating Cr phytoextraction of hyperaccumulator Leersia hexandra Swartz. Environ. Res. 2023, 228, 115846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroh, G.E.; Pilon, M. Regulation of Iron Homeostasis and Use in Chloroplasts. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecchia, F.D.; Nardi, S.; Santoro, V.; Pilon-Smits, E.; Schiavon, M. Brassica juncea and the Se-hyperaccumulator Stanleya pinnata exhibit a different pattern of chromium and selenium accumulation and distribution while activating distinct oxidative stress-response signatures. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 320, 121048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magoc, T.; Salzberg, S.L. FLASH: Fast length adjustment of short reads to improve genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 2957–2963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gu, J. fastp: An ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, 884–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callahan, B.J.; McMurdie, P.J.; Rosen, M.J.; Han, A.W.; Johnson, A.J.A.; Holmes, S.P. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods 2016, 13, 581–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolyen, E.; Rideout, J.R.; Dillon, M.R.; Bokulich, N.; Abnet, C.C.; Al-Ghalith, G.A.; Alexander, H.; Alm, E.J.; Arumugam, M.; Asnicar, F.; et al. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 852–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, X.; Zhang, X.; Lin, Y.; Lv, J.; Jiang, M.; Cheng, S.; Yan, J. Pyrrhotite Facilitates Growth and Cr Accumulation in Leersia hexandra Swartz for Effective Cr(VI) Removal in Constructed Wetlands. Toxics 2026, 14, 107. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14010107

Zhang X, Zhang X, Lin Y, Lv J, Jiang M, Cheng S, Yan J. Pyrrhotite Facilitates Growth and Cr Accumulation in Leersia hexandra Swartz for Effective Cr(VI) Removal in Constructed Wetlands. Toxics. 2026; 14(1):107. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14010107

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Xinyue, Xuehong Zhang, Yue Lin, Jiang Lv, Minmin Jiang, Sijia Cheng, and Jun Yan. 2026. "Pyrrhotite Facilitates Growth and Cr Accumulation in Leersia hexandra Swartz for Effective Cr(VI) Removal in Constructed Wetlands" Toxics 14, no. 1: 107. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14010107

APA StyleZhang, X., Zhang, X., Lin, Y., Lv, J., Jiang, M., Cheng, S., & Yan, J. (2026). Pyrrhotite Facilitates Growth and Cr Accumulation in Leersia hexandra Swartz for Effective Cr(VI) Removal in Constructed Wetlands. Toxics, 14(1), 107. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14010107