Impact of Air Pollution Control Devices on VOC Profiles and Emissions from Municipal Waste Incineration Plant

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Municipal Waste

2.2. Overview of Waste Incineration Plants

2.3. Field Sampling Method

2.4. Analytical Method

2.5. Quality Control and Quality Assurance

3. Results and Discussion

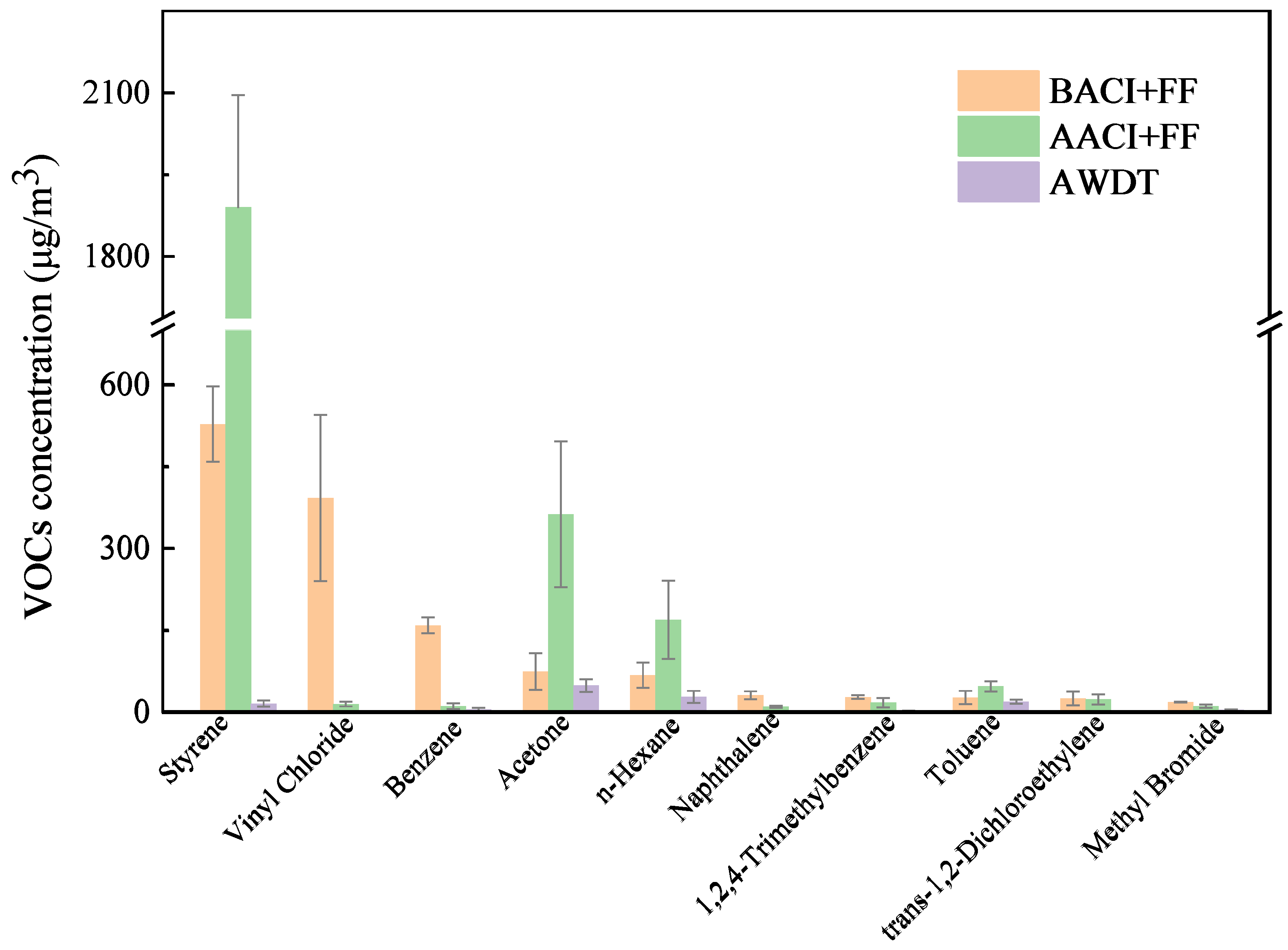

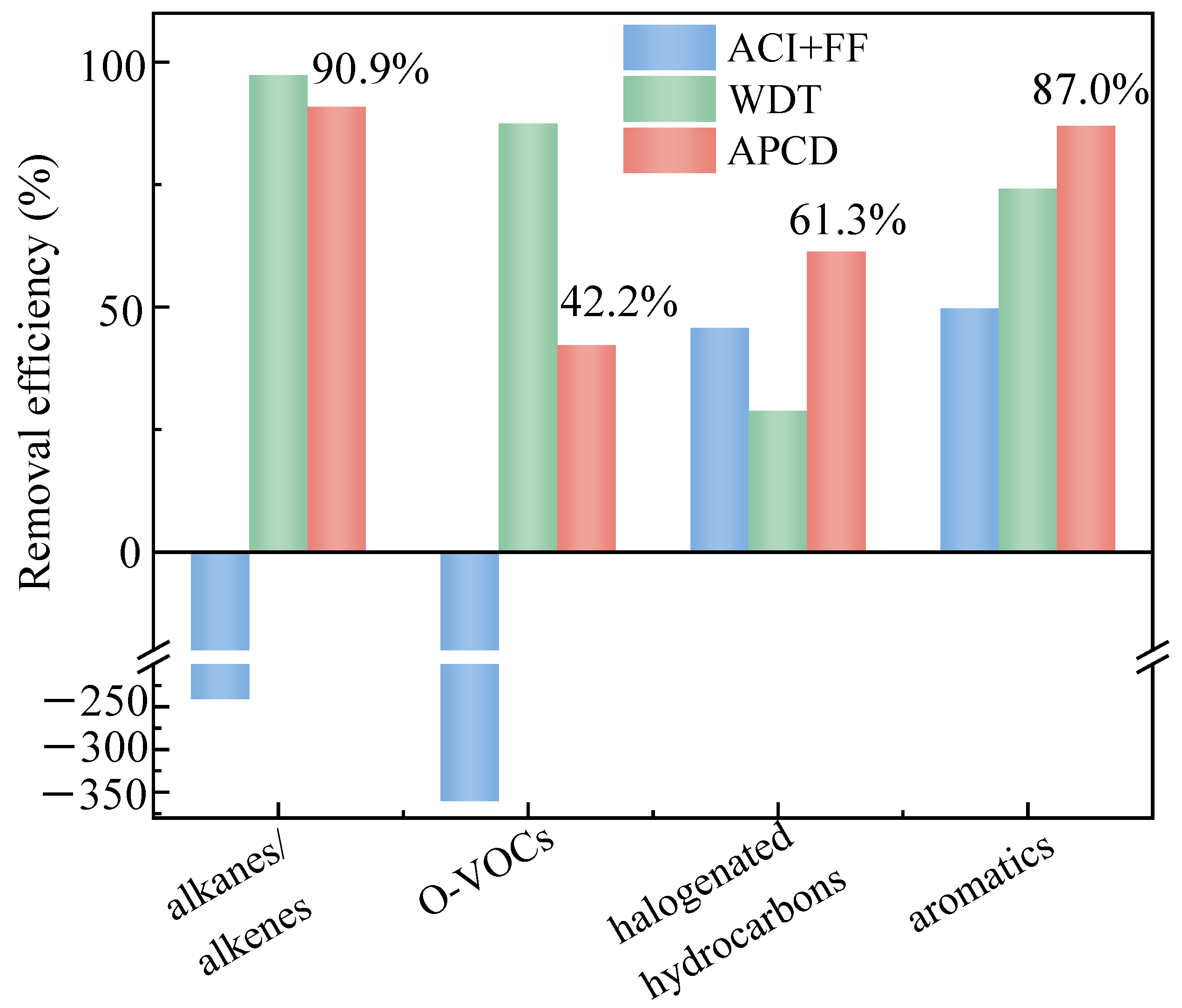

3.1. Characteristics of VOCs Generation During Waste Incineration

3.2. Distribution Characteristics of Alkanes/Alkenes

3.3. Distribution Characteristics of O-VOCs

3.4. Distribution Characteristics of Aromatics

3.5. Distribution Characteristics of Halogenated Hydrocarbons

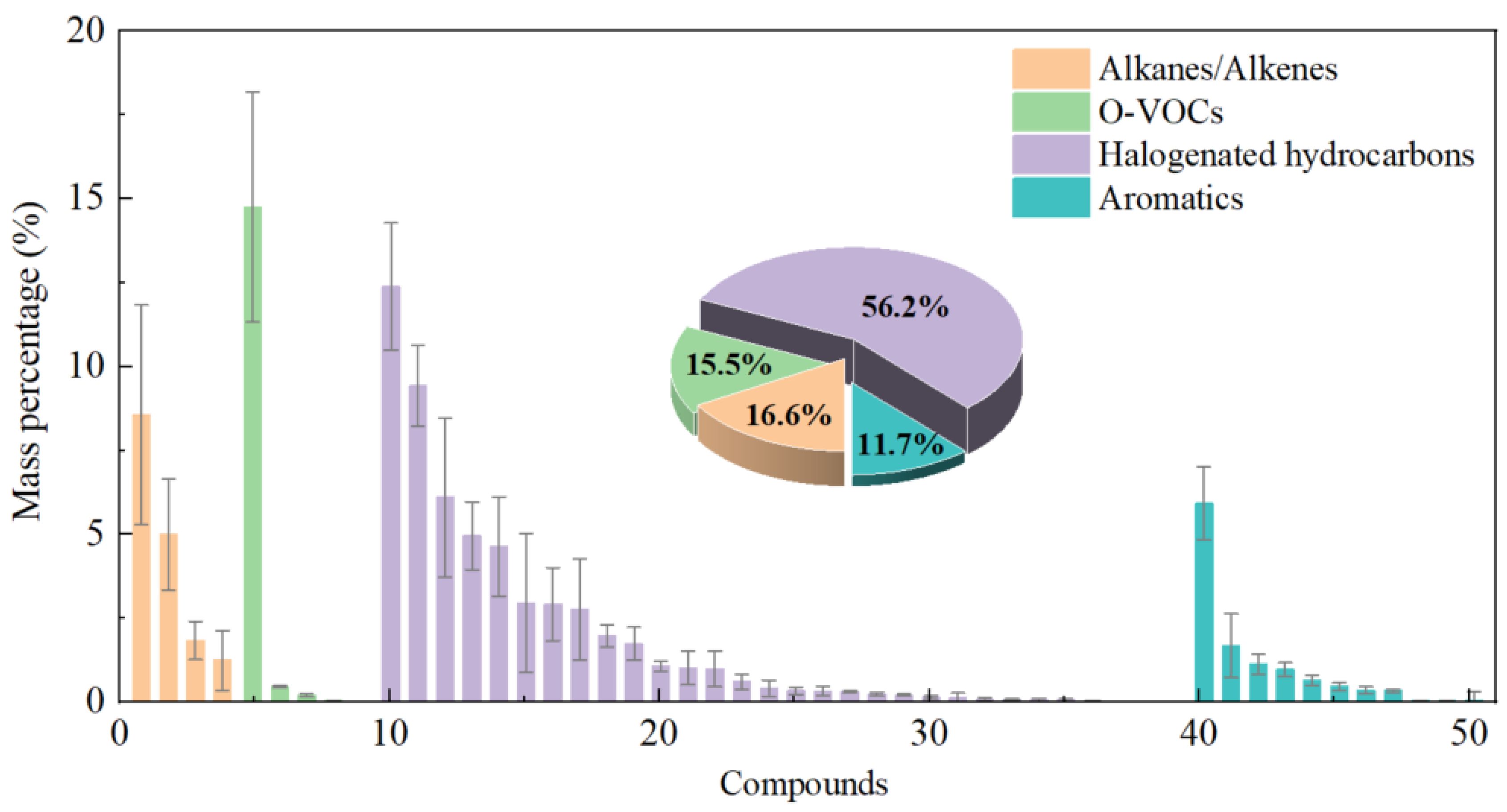

3.6. VOC Emission Characteristics in MWI Flue Gas

| Region | Number of VOCs | VOCs Concentration (μg/m3) | Emission Factor (ng/g-Waste) | VOCs Characters | Typical Substance | Sampling Method | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Guangzhou Province | 25 | 270.63 ± 2.84 | - | aromatics (63.66%), halo hydrocarbons (11.49%), alkanes (16.17%), O–VOCs (3.19%) | Chlorobenzene, tetrachloroethylene | adsorption tube | [9] |

| Switzerland (Hinwil) | 25 | 16.75 | - | Alkanes (61.37%), aromatics (30.63%) O–VOCs (8.00%) | p-xylene, nonane, benzaldehyde | adsorption tube | [8] |

| Switzerland (Giubiasco) | 25 | 20.75–27.08 | - | alkanes (51.58%), aromatics (36.09%) O–VOCs (12.33%) | p-xylene, nonane, benzaldehyde | ||

| Henan Province | 89 | 4.28 mg/m3 | 16 × 103 | aromatics (38.4%), halo hydrocarbons (28.8%), O–VOCs (14.3%), alkanes (12.8%) | Tetrachloroethylene, Hexachloro-1,3-butadiene, Acetaldehyde | Tedlar bag, summa canister, adsorption tube | [10] |

| Shandong province | 30 | 116.3 ± 15.7 | 0.7 × 103 ± 0.1 × 103 | aromatics (28–47%), halo aromatics (22–52%), halo aliphatics (19–30%), Chennai (0.3–0.5%) | Ethylbenzene, m/p-xylene, tetrachloroethylene | Tedlar bag | [45] |

| North China plan | 102 | 635.3 ± 588.8 | 2.43 × 103 ± 2.27 × 103 | aromatics (62.1%), O–VOCs (16.0%), halo hydrocarbons (10.0%), alkanes (6.6%) | acetone, 1,2,4-trimethylbenzene, benzene | Tedlar bag | [11] |

| Beijing | - | - | 5.24 × 103 ± 0.15 × 103 | - | [53] | ||

| China | 50 | 338.2 ± 98.0 | 1.89 × 103 ± 0.55 × 103 | halo hydrocarbons (56.2%), aromatics (11.7%%), O–VOCs (15.5%), alkanes (16.6%) | Acetone, Bromobenzene, n-hexane, toluene | adsorption tube | This study |

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Statistics, N.B. Removal and Disposal of Urban Domestic Waste; The National Bureau of Statistics (NBS): Beijing, China, 2024. (In Chinese)

- Zhou, Q.; Yang, J.; Liu, M.; Liu, Y.; Sarnat, S.; Bi, J. Toxicological Risk by Inhalation Exposure of Air Pollution Emitted from China’s Municipal Solid Waste Incineration. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 11490–11499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, L.; Guo, J.; Wan, R.; Jia, M.; Qu, J.; Li, L.; Bo, X. Air pollutant emissions and reduction potentials from municipal solid waste incineration in China. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 319, 121021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Jiang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Yan, J. Disposal technology and new progress for dioxins and heavy metals in fly ash from municipal solid waste incineration: A critical review. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 311, 119878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Shi, N.; Wang, T.; Yang, J.; Liu, P.-F.; Zhang, Y.; Pan, W.-P. Significant enhancement of VOCs conversion by facile mechanochemistry coupled MnO2 modified fly ash: Mechanism and application. Fuel 2021, 304, 121443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, D.; Cao, Z.; Gong, G.; Wang, C.; Gao, Y. VOCs inhibited asphalt mixtures for green pavement: Emission reduction behavior, environmental health impact and road performance. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 489, 144671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Feng, Z.; Chen, X.; Xia, M.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, F.; Hua, C.; et al. Overlooked Significance of Reactive Chlorines in the Reacted Loss of VOCs and the Formation of O3 and SOA. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 59, 6155–6166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setyan, A.; Patrick, M.; Wang, J. Very low emissions of airborne particulate pollutants measured from two municipal solid waste incineration plants in Switzerland. Atmos. Environ. 2017, 166, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Wang, B.; He, J.; Tang, X.; Luo, W.; Wang, C. Source Fingerprints of Volatile Organic Compounds Emitted from A Municipal Solid Waste Incineration Power Plant in Guangzhou, China. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2012, 12, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Li, P.Z.; Dong, R.Z.; Yan, L.Y.; Liu, D.; Hao, X.Q.; Mao, J. VOCs emission characteristics of a typical domestic waste incineration power plant in Henan province. China. Res. Environ. Sci. 2022, 35, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Wang, Z.; Yang, Y.; Wang, M.; Jing, X.; Li, G.; Yan, J.; Zhao, L.; Nie, L.; Wang, Y.; et al. Characteristics, secondary transformation and odor activity evaluation of VOCs emitted from municipal solid waste incineration power plant. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 326, 116703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Liu, J.; Wang, T.; Sui, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Pan, W.-P. Reductions in Volatile Organic Compound Emissions from Coal-Fired Power Plants by Combining Air Pollution Control Devices and Modified Fly Ash. Energy Fuels 2019, 33, 2926–2933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, P.; Wu, J.; Zhong, L.; Pan, W.-P. VOC emissions characteristics and cooperative control by combustion adjustment and APCDs in supercritical coal-fired power plants. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 449, 140177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Wang, J.; Cheng, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, T.; Pan, W.-P. Distribution and emission of speciated volatile organic compounds from a coal-fired power plant with ultra-low emission technologies. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 264, 121686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Liu, W.; Guan, W.; Zhu, S.; Jia, J.; Wu, X.; Lei, R.; Jia, T.; He, Y. Effects of air pollution control devices on volatile organic compounds reduction in coal-fired power plants. Sci. Total. Environ. 2021, 782, 146828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D7582–15; Standard Test Methods for Proximate Analysis of Coal and Coke by Macro Thermogravimetric Analysis. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2015.

- ASTM D5865-04; Standard Test Method for Gross Calorific Value of Coal and Coke. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2004.

- HJ 734-2014; Stationary Source Emission—Determination of Volatile Organic Compounds-Sorbent Adsorption and Thermal Desorption Gas Chromatography Mass Spectrometry Method. Standardization Administration of China: Beijing, China, 2014. (In Chinese)

- Qin, L.; Han, J.; Zhao, B.; Wang, Y.; Chen, W.; Xing, F. Thermal degradation of medical plastic waste by in-situ FTIR, TG-MS and TG-GC/MS coupled analyses. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2018, 136, 132–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.Y.; Ji, Y.; Buekens, A.; Ma, Z.Y.; Jin, Y.Q.; Li, X.D.; Yan, J.H. Activated carbon treatment of municipal solid waste incineration flue gas. Waste Manag. Res. 2013, 31, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, H.; Li, J.; Yang, L. Adsorption of Volatile Organic Compounds at Medium-High Temperature Conditions by Activated Carbons. Energy Fuels 2019, 34, 3679–3690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, J.-H.; Chiang, H.-M.; Huang, G.-Y.; Chiang, H.-L. Adsorption characteristics of acetone, chloroform and acetonitrile on sludge-derived adsorbent, commercial granular activated carbon and activated carbon fibers. J. Hazard. Mater. 2008, 154, 1183–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Tang, M.; Li, H.; Wang, L.; Lu, S. Adsorption of multicomponent VOCs on various biomass-derived hierarchical porous carbon: A study on adsorption mechanism and competitive effect. Chemosphere 2023, 313, 137513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treese, J.; Pasel, C.; Luckas, M.; Bathen, D. Chemical Surface Characterization of Activated Carbons by Adsorption Excess of Probe Molecules. Chem. Eng. Technol. 2016, 39, 1144–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Jahandar Lashaki, M.; Fayaz, M.; Hashisho, Z.; Philips, J.H.; Anderson, J.E.; Nichols, M. Adsorption and Desorption of Mixtures of Organic Vapors on Beaded Activated Carbon. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 8341–8350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolar, P.; Kastner, J.R. Low-temperature catalytic oxidation of aldehyde mixtures using wood fly ash: Kinetics, mechanism, and effect of ozone. Chemosphere 2010, 78, 1110–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Premkumar, P.; Saravanan, C.G.; Nalluri, P.; Seeman, M.; Vikneswaran, M.; Madheswaran, D.K.; Femilda Josephin, J.S.; Chinnathambi, A.; Pugazhendhi, A.; Varuvel, E.G. Production of liquid hydrocarbon fuels through catalytic cracking of high and low-density polyethylene medical wastes using fly ash as a catalyst. Process. Saf. Environ. Prot. 2024, 187, 459–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, T.; Zhong, L.; Serageldin, M.A.; Pan, W.-P. Review of organic pollutants in coal combustion processes and control technologies. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2025, 109, 101231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Bai, X.; Liu, W.; Lin, S.; Liu, S.; Luo, L.; Guo, Z.; Zhao, S.; Lv, Y.; Zhu, C.; et al. Non-Negligible Stack Emissions of Noncriteria Air Pollutants from Coal-Fired Power Plants in China: Condensable Particulate Matter and Sulfur Trioxide. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 6540–6550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Li, X.; Feng, X.; Li, X.; Xu, X. Synthesis and characterization of mesoporous graphite carbon, and adsorption performance for benzene. J. Porous Mater. 2016, 23, 957–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Tong, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Zhao, Z. A Microporous Graphitized Biocarbon with High Adsorption Capacity toward Benzene Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs) from Humid Air at Ultralow Pressures. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2016, 55, 3765–3774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, T.; Cheng, J.; Zhang, Y.; Pan, W.-P. Distribution of Organic Compounds in Coal-Fired Power Plant Emissions. Energy Fuels 2019, 33, 5430–5437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, Y.; Pan, C.; Song, K.; Chol Nam, J.; Wu, F.; You, Z.; Hao, Z.; Li, J.; Zhang, Z. Bamboo-derived hydrophobic porous graphitized carbon for adsorption of volatile organic compounds. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 461, 141979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T.; Bian, Y.; Li, J.; Ma, X.; Yang, L.; Zhou, L.; Wu, H. Nitrogen-doped porous biochar for selective adsorption of toluene under humid conditions. Fuel 2023, 334, 126452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; He, R. Competitive adsorption characteristics of gasoline evaporated VOCs in microporous activated carbon by molecular simulation. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 2023, 121, 108444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pytlarczyk, M.; Dmochowska, E.; Czerwiński, M.; Herman, J. Effect of lateral substitution by chlorine and fluorine atoms of 4-alkyl-p-terphenyls on mesomorphic behaviour. J. Mol. Liq. 2019, 292, 111379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Visser, S.P. Van der Waals Equation of State Revisited: Importance of the Dispersion Correction. J. Phys. Chem. B 2011, 115, 4709–4717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Ding, X.; Chang, K.; Zeng, Z.; Hou, Y.; Huang, Z. In situ DRIFTS combined with GC–MS to identify the catalytic oxidation process of dibenzofuran over activated carbon-supported transition metals oxide catalysts. Fuel 2022, 312, 122492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, X.; Long, Y.; Wang, W.; Shao, M.; Wu, Z. Structural effect and reaction mechanism of MnO2 catalysts in the catalytic oxidation of chlorinated aromatics. Chin. J. Catal. 2019, 40, 638–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Wu, Y.; Liu, S.; Tang, M.; Lu, S. Distribution and emission characteristics of filterable and condensable particulate matter in the flue gas emitted from an ultra-low emission coal-fired power plant. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 107667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Xu, Z.; Liu, S.; Tang, M.; Lu, S. Emission Characteristics of Particulate Matter from Coal-Fired Power Units with Different Load Conditions. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2022, 233, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Y.; Liu, X.; Han, J.; Zou, Y.; Huang, Y.; Wang, H.; Liu, L.; Xu, M. Study on the removal characteristics of different air pollution control devices for condensable particulate matter in coal-fired power plants. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2022, 29, 34714–34724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, J.; Zhao, H.; Wang, B.; Han, B.; Ling, H.; Ju, F. Emission characteristics of condensable particulate matter (CPM) from FCC flue gas. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 882, 163533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; He, H.; Yang, C.; Zeng, G.; Li, X.; Chen, H.; Yu, G. Challenges and solutions for biofiltration of hydrophobic volatile organic compounds. Biotechnol. Adv. 2016, 34, 1091–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S. VOCs Emission Characteristics of Typical Combustion Sources and the Influence of Air Pollution Control Devices; Chang’an University: Xi’an, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, M.A.; Lin, L.H.; Lippitt, J.M.; Herren, S.L. Trihalomethanes as initiators and promoters of carcinogenesis. Environ. Health Perspect. 1982, 46, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mu, X.; Ding, H.; Pan, W.; Zhou, Q.; Du, W.; Qiu, K.; Ma, J.; Zhang, K. Research progress in catalytic oxidation of volatile organic compound acetone. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 105650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couri, D.; Milks, M. Toxicity and Metabolism of the Neurotoxic Hexacarbons n-Hexane, 2-Hexanone, and 2,5-Hexanedione. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 1982, 22, 145–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filley, C.M.; Halliday, W.; Kleinschmidt-Demasters, B.K. The Effects of Toluene on the Central Nervous System. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2004, 63, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gałęzowska, G.; Chraniuk, M.; Wolska, L. In vitro assays as a tool for determination of VOCs toxic effect on respiratory system: A critical review. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2016, 77, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangotra, A.; Singh, S.K. Volatile organic compounds: A threat to the environment and health hazards to living organisms—A review. J. Biotechnol. 2024, 382, 51–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beylot, A.; Hochar, A.; Michel, P.; Descat, M.; Ménard, Y.; Villeneuve, J. Municipal Solid Waste Incineration in France: An Overview of Air Pollution Control Techniques, Emissions, and Energy Efficiency. J. Ind. Ecol. 2018, 22, 1016–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Song, G.; Liu, J.; Liu, X.; Wang, H.; Hao, Z. A comprehensive emission inventory of air pollutants from municipal solid waste incineration in China’s megacity, Beijing based on the field measurements. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 948, 174806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Organics | Inorganics | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plastic/Rubber Products | Cotton fabric | Woodware | Food waste | Medicine | Paper products | Glassware/metalware/muck |

| 22% | 7% | 6% | 37% | 4% | 11% | 13% |

| Materials | Elemental Analysis (Dry Basis, wt.%) | Proximate Analysis (wt.%) | HHV (MJ/kg) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | H | O | N | S | VM | MO | FC | Ash | ||

| Municipal wastes | 52.9 | 7.0 | 29.8 | 1.3 | 0.7 | 78.1 | 3.8 | 9.8 | 8.3 | 20.19 ± 0.68 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, J.; Zhao, D.; Wu, F.; Luo, H.; Hou, D.; Peng, Y. Impact of Air Pollution Control Devices on VOC Profiles and Emissions from Municipal Waste Incineration Plant. Toxics 2025, 13, 1067. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121067

Liu J, Zhao D, Wu F, Luo H, Hou D, Peng Y. Impact of Air Pollution Control Devices on VOC Profiles and Emissions from Municipal Waste Incineration Plant. Toxics. 2025; 13(12):1067. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121067

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Jun, Duanhe Zhao, Fei Wu, Huanhuan Luo, Daxiang Hou, and Yue Peng. 2025. "Impact of Air Pollution Control Devices on VOC Profiles and Emissions from Municipal Waste Incineration Plant" Toxics 13, no. 12: 1067. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121067

APA StyleLiu, J., Zhao, D., Wu, F., Luo, H., Hou, D., & Peng, Y. (2025). Impact of Air Pollution Control Devices on VOC Profiles and Emissions from Municipal Waste Incineration Plant. Toxics, 13(12), 1067. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121067