Co-Culture of Primary Human Bronchial Epithelial Cells at the Air–Liquid Interface and THP-1 Macrophages to Investigate the Toxicity of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Reagents

2.2. Air–Liquid Interface Human Bronchial Epithelial Cell Cultures

2.3. THP-1 Cell Cultures

2.4. HBEC–Macrophage Co-Culture

2.5. Chemical Exposures

2.6. Transepithelial Electrical Resistance Measurement

2.7. Lactate Dehydrogenase Cytotoxicity Assay

2.8. Evaluation of Gene Expression by qPCR

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Importance of Co-Culture Models for Respiratory Toxicity Testing

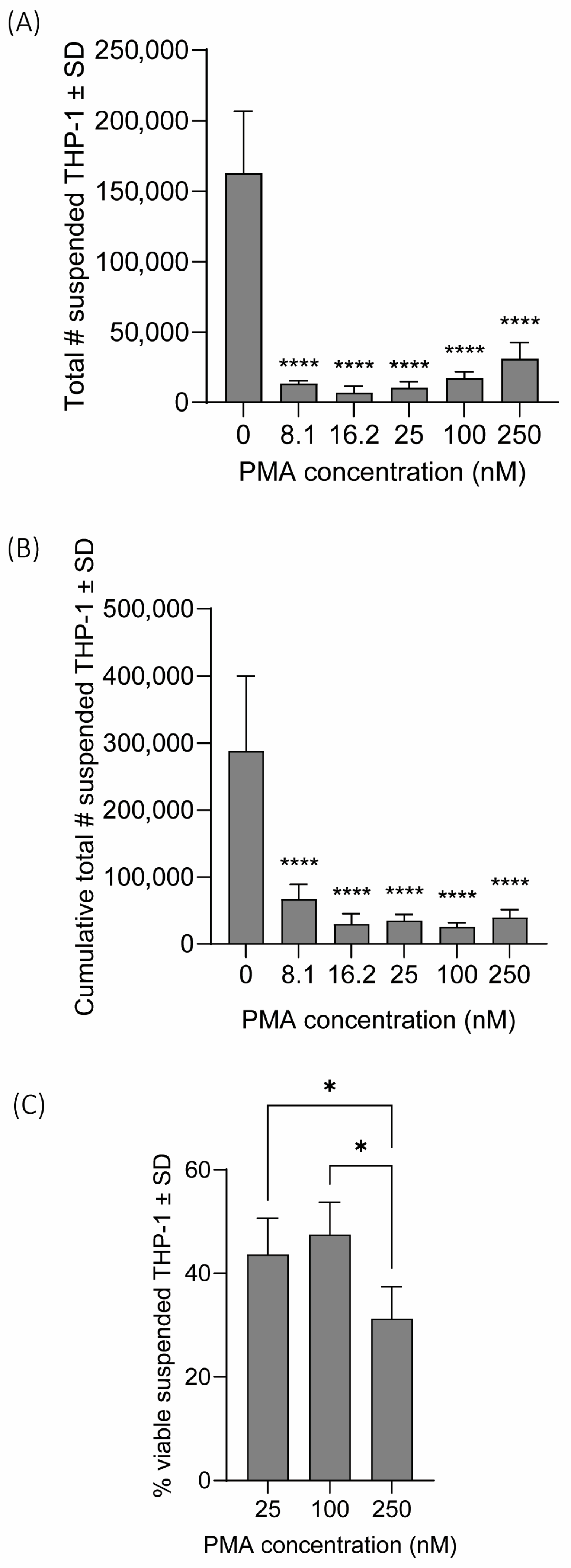

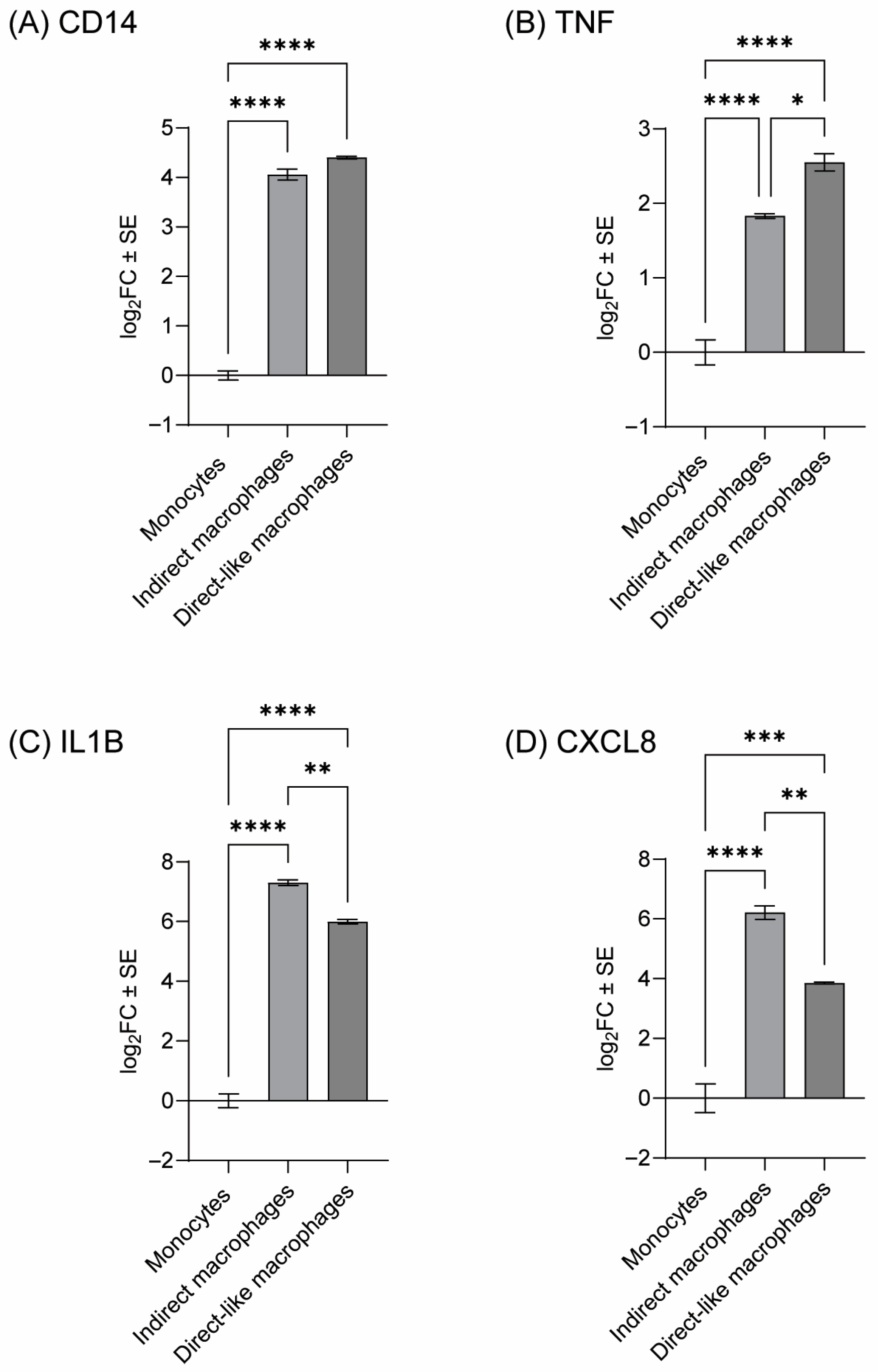

3.2. Confirmation of THP-1 Differentiation and Identifying Optimal PMA Concentration

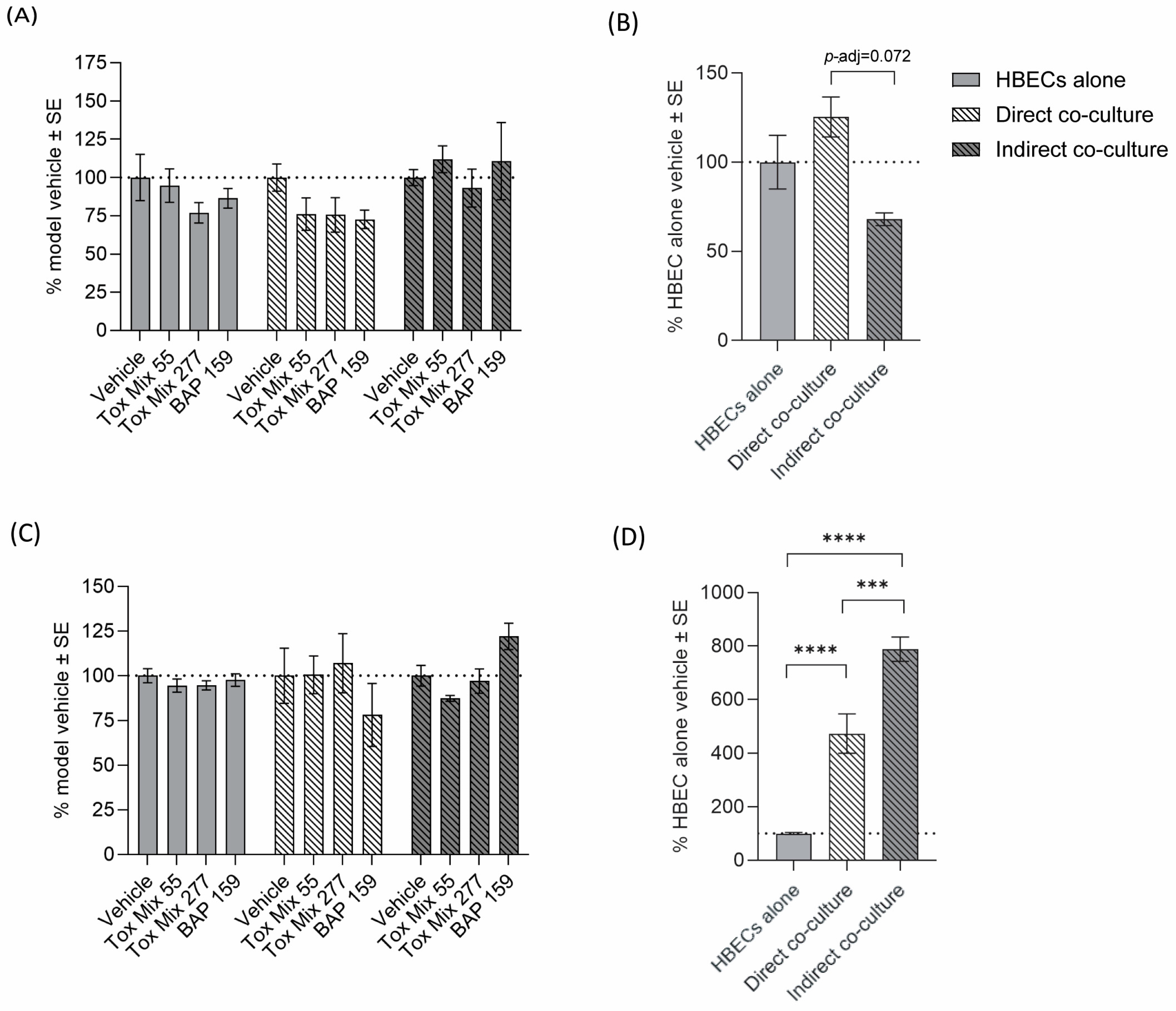

3.3. Barrier Integrity and Cytotoxicity

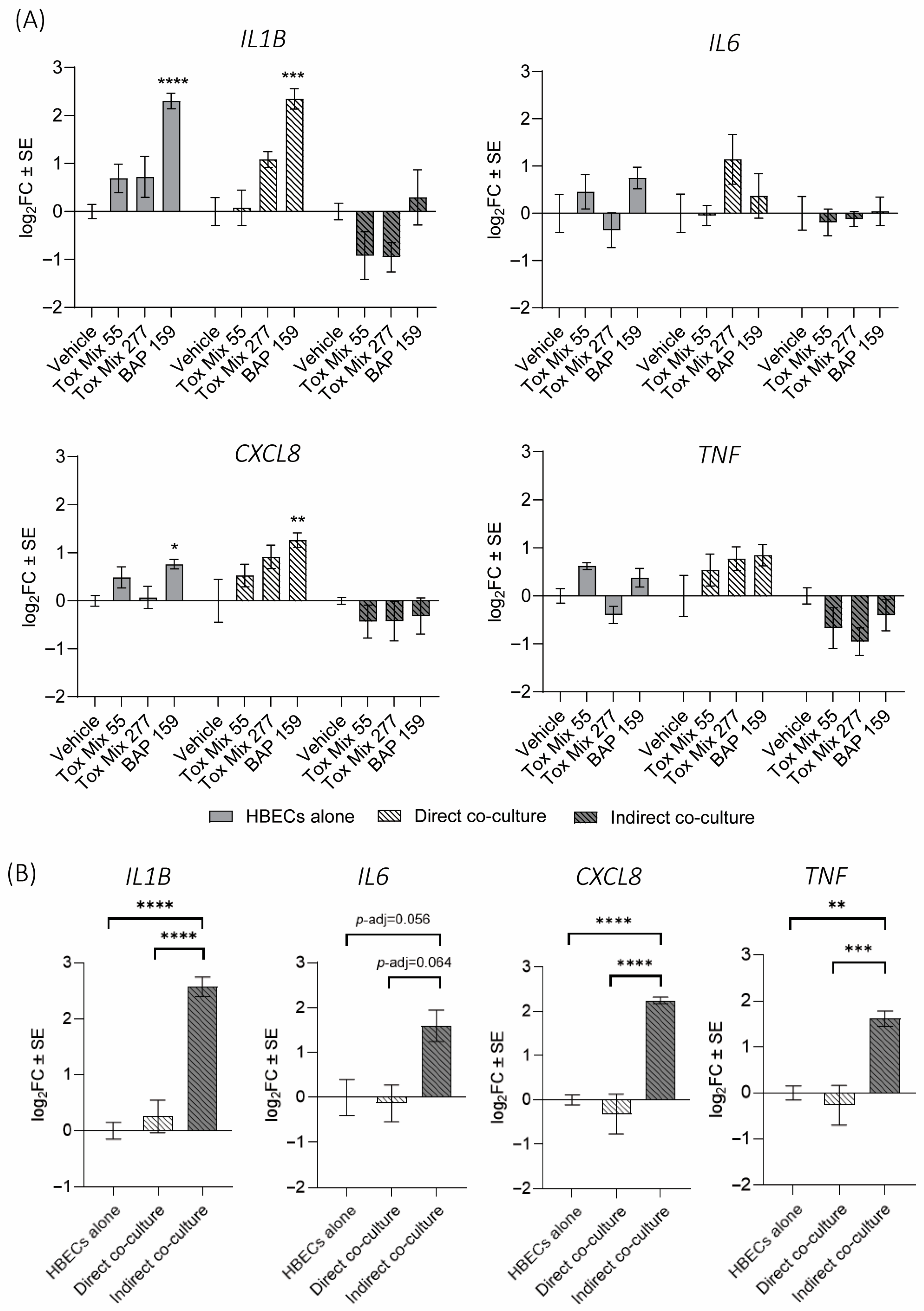

3.4. Cytokine Gene Expression in HBEC

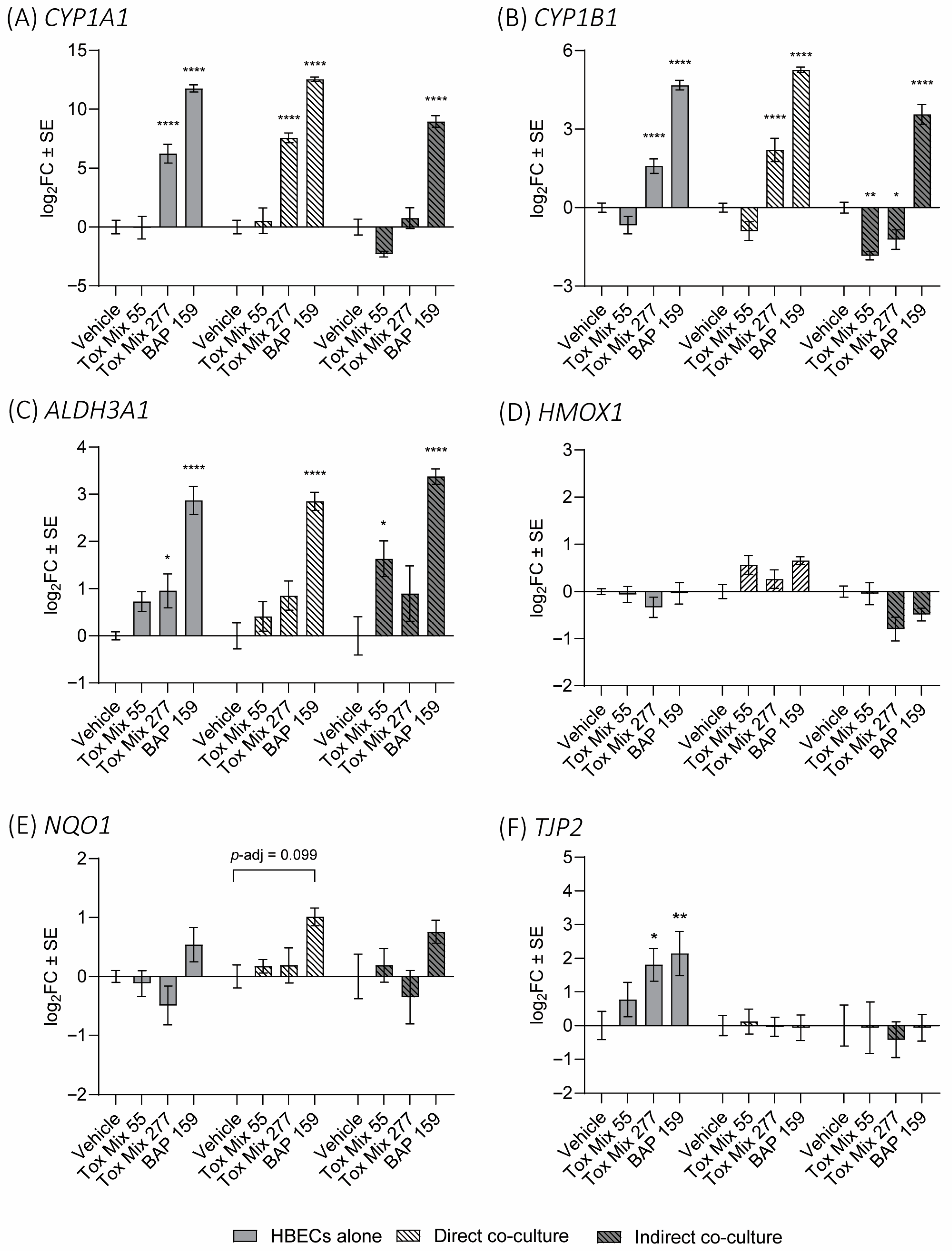

3.5. PAH Biomarker Expression in HBEC

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hewitt, R.J.; Lloyd, C.M. Regulation of immune responses by the airway epithelial cell landscape. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2021, 21, 347–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgoyne, R.A.; Fisher, A.J.; Borthwick, L.A. The Role of Epithelial Damage in the Pulmonary Immune Response. Cells 2021, 10, 2763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, I.; Badran, G.; Verdin, A.; Ledoux, F.; Roumié, M.; Courcot, D.; Garçon, G. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon derivatives in airborne particulate matter: Sources, analysis and toxicity. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2018, 16, 439–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barraza-Villarreal, A.M.; Escamilla-Nuñez, M.C.M.; Schilmann, A.M.; Hernandez-Cadena, L.M.; Li, Z.; Romanoff, L.; Sjödin, A.; Del Río-Navarro, B.E.; Díaz-Sanchez, D.; Díaz-Barriga, F.; et al. Lung Function, Airway Inflammation, and Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons Exposure in Mexican Schoolchildren. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2014, 56, 415–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Zhang, L.; Liu, H.; Huang, W. Systemic inflammation mediates environmental polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons to increase chronic obstructive pulmonary disease risk in United States adults: A cross-sectional NHANES study. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1248812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Låg, M.; Øvrevik, J.; Refsnes, M.; Holme, J.A. Potential role of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in air pollution-induced non-malignant respiratory diseases. Respir. Res. 2020, 21, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Øvrevik, J.; Refsnes, M.; Holme, J.A.; Schwarze, P.E.; Låg, M. Mechanisms of chemokine responses by polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in bronchial epithelial cells: Sensitization through toll-like receptor-3 priming. Toxicol. Lett. 2013, 219, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Øvrevik, J.; Låg, M.; Lecureur, V.; Gilot, D.; Lagadic-Gossmann, D.; Refsnes, M.; Schwarze, P.E.; Skuland, T.; Becher, R.; Holme, J.A. AhR and Arnt differentially regulate NF-κB signaling and chemokine responses in human bronchial epithelial cells. Cell Commun. Signal. 2014, 12, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayati, A.; Le Ferrec, E.; Holme, J.A.; Fardel, O.; Lagadic-Gossmann, D.; Øvrevik, J. Calcium signaling and β2-adrenergic receptors regulate 1-nitropyrene induced CXCL8 responses in BEAS-2B cells. Toxicol. Vitr. 2014, 28, 1153–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Siddens, L.K.; Heine, L.K.; Sampson, D.A.; Yu, Z.; Fischer, K.A.; Löhr, C.V.; Tilton, S.C. Comparative mechanisms of PAH toxicity by benzo[a]pyrene and dibenzo[def,p]chrysene in primary human bronchial epithelial cells cultured at air-liquid interface. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2019, 379, 114644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogel, C.F.A.; Kado, S.Y.; Kobayashi, R.; Liu, X.; Wong, P.; Na, K.; Durbin, T.; Okamoto, R.A.; Kado, N.Y. Inflammatory marker and aryl hydrocarbon receptor-dependent responses in human macrophages exposed to emissions from biodiesel fuels. Chemosphere 2019, 220, 993–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Liu, J.; Kong, Q.; Li, L.; Gao, J.; Fang, L.; Liu, Z.; Fan, X.; Li, C.; Lu, Q.; et al. Cytotoxicity and inflammatory effects in human bronchial epithelial cells induced by polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons mixture. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2021, 41, 1803–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-Gómez, G.; Karasová, M.; Tylichová, Z.; Kabátková, M.; Hampl, A.; Matthews, J.; Neča, J.; Ciganek, M.; Machala, M.; Vondráček, J. Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor (AhR) Limits the Inflammatory Responses in Human Lung Adenocarcinoma A549 Cells via Interference with NF-κB Signaling. Cells 2022, 11, 707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-Gómez, G.; Rocha-Zavaleta, L.; Rodríguez-Sosa, M.; Petrosyan, P.; Rubio-Lightbourn, J. Benzo[a]pyrene activates an AhR/Src/ERK axis that contributes to CYP1A1 induction and stable DNA adducts formation in lung cells. Toxicol. Lett. 2018, 289, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N’Diaye, M.; Le Ferrec, E.; Lagadic-Gossmann, D.; Corre, S.; Gilot, D.; Lecureur, V.; Monteiro, P.; Rauch, C.; Galibert, M.-D.; Fardel, O. Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor- and Calcium-dependent Induction of the Chemokine CCL1 by the Environmental Contaminant Benzo[a]pyrene. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 19906–19915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osgood, R.S.; Upham, B.L.; Hill, T.; Helms, K.L.; Velmurugan, K.; Babica, P.; Bauer, A.K. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon-Induced Signaling Events Relevant to Inflammation and Tumorigenesis in Lung Cells Are Dependent on Molecular Structure. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e65150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayner, R.E.; Makena, P.; Prasad, G.L.; Cormet-Boyaka, E. Optimization of Normal Human Bronchial Epithelial (NHBE) Cell 3D Cultures for in vitro Lung Model Studies. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, X.; Coyle, J.P.; Xiong, R.; Wang, Y.; Heflich, R.H.; Ren, B.; Gwinn, W.M.; Hayden, P.; Rojanasakul, L. Invited review: Human air-liquid-interface organotypic airway tissue models derived from primary tracheobronchial epithelial cells—Overview and perspectives. Vitr. Cell. Dev. Biol. Anim. 2021, 57, 104–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faber, S.C.; A McNabb, N.; Ariel, P.; Aungst, E.R.; McCullough, S.D. Exposure Effects Beyond the Epithelial Barrier: Transepithelial Induction of Oxidative Stress by Diesel Exhaust Particulates in Lung Fibroblasts in an Organotypic Human Airway Model. Toxicol. Sci. 2020, 177, 140–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papazian, D.; Würtzen, P.A.; Hansen, S.W. Polarized Airway Epithelial Models for Immunological Co-Culture Studies. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 2016, 170, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothen-Rutishauser, B.M.; Kiama, S.G.; Gehr, P. A Three-Dimensional Cellular Model of the Human Respiratory Tract to Study the Interaction with Particles. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2005, 32, 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takam, P.; Schäffer, A.; Laovitthayanggoon, S.; Charerntantanakul, W.; Sillapawattana, P. Toxic effect of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) on co-culture model of human alveolar epithelial cells (A549) and macrophages (THP-1). Environ. Sci. Eur. 2024, 36, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Zhang, X.; Liu, X.; Zheng, J. Co-culture of human alveolar epithelial (A549) and macrophage (THP-1) cells to study the potential toxicity of ambient PM2.5: A comparison of growth under ALI and submerged conditions. Toxicol. Res. 2020, 9, 636–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashrin, A.; Anna, E.; Peyret, E.; Barbier, G.; Floreani, M.; Pointart, C.; Medus, D.; Fayet, G.; Rotureau, P.; Loret, T.; et al. Evaluation of the toxicity of combustion smokes at the air–liquid interface: A comparison between two lung cell models and two exposure methods. Arch. Toxicol. 2025, 99, 1471–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezzulo, A.A.; Starner, T.D.; Scheetz, T.E.; Traver, G.L.; Tilley, A.E.; Harvey, B.-G.; Crystal, R.G.; McCray, P.B., Jr.; Zabner, J. The air-liquid interface and use of primary cell cultures are important to recapitulate the transcriptional profile of in vivo airway epithelia. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2011, 300, L25–L31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdez, R.M.; Rivera, B.N.; Chang, Y.; Pennington, J.M.; Fischer, K.A.; Löhr, C.V.; Tilton, S.C. Assessing susceptibility for polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon toxicity in an in vitro 3D respiratory model for asthma. Front. Toxicol. 2024, 6, 1287863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonser, L.R.; Koh, K.D.; Johansson, K.; Choksi, S.P.; Cheng, D.; Liu, L.; Sun, D.I.; Zlock, L.T.; Eckalbar, W.L.; Finkbeiner, W.E.; et al. Flow-Cytometric Analysis and Purification of Airway Epithelial-Cell Subsets. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2021, 64, 308–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, B.N.; Ghetu, C.C.; Chang, Y.; Truong, L.; Tanguay, R.L.; Anderson, K.A.; Tilton, S.C. Leveraging Multiple Data Streams for Prioritization of Mixtures for Hazard Characterization. Toxics 2022, 10, 651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martignoni, M.; Groothuis, G.M.M.; de Kanter, R. Species differences between mouse, rat, dog, monkey and human CYP-mediated drug metabolism, inhibition and induction. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2006, 2, 875–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moorthy, B.; Chu, C.; Carlin, D.J. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons: From Metabolism to Lung Cancer. Toxicol. Sci. 2015, 145, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boei, J.J.W.A.; Vermeulen, S.; Klein, B.; Hiemstra, P.S.; Verhoosel, R.M.; Jennen, D.G.J.; Lahoz, A.; Gmuender, H.; Vrieling, H. Xenobiotic metabolism in differentiated human bronchial epithelial cells. Arch. Toxicol. 2017, 91, 2093–2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colvin, V.C.; Bastin, K.M.; Siddens, L.K.; Maier, M.L.V.; Williams, D.E.; Smith, J.N.; Tilton, S.C. Building a predictive model for polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon dosimetry in organotypically cultured human bronchial epithelial cells using benzo[a]pyrene. Toxicol. Rep. 2025, 15, 102133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, S.G.; Hennen, J.; Serchi, T.; Blömeke, B.; Gutleb, A.C. Potential of coculture in vitro models to study inflammatory and sensitizing effects of particles on the lung. Toxicol. Vitr. 2011, 25, 1516–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Zhang, X.; Liu, X.; Zheng, J.; Chen, R.; Kan, H. Ambient fine particulate matter induce toxicity in lung epithelial-endothelial co-culture models. Toxicol. Lett. 2019, 301, 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kletting, S. Co-culture of human alveolar epithelial (hAELVi) and macrophage (THP-1) cell lines. ALTEX 2018, 35, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arezki, Y.; Cornacchia, J.; Rapp, M.; Lebeau, L.; Pons, F.; Ronzani, C. A Co-Culture Model of the Human Respiratory Tract to Discriminate the Toxicological Profile of Cationic Nanoparticles According to Their Surface Charge Density. Toxics 2021, 9, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kämpfer, A.A.; Urbán, P.; Gioria, S.; Kanase, N.; Stone, V.; Kinsner-Ovaskainen, A. Development of an in vitro co-culture model to mimic the human intestine in healthy and diseased state. Toxicol. Vitr. 2017, 45, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phuangbubpha, P.; Thara, S.; Sriboonaied, P.; Saetan, P.; Tumnoi, W.; Charoenpanich, A. Optimizing THP-1 Macrophage Culture for an Immune-Responsive Human Intestinal Model. Cells 2023, 12, 1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhu, M.; Hong, Z.; Chen, C. Co-culturing polarized M2 Thp-1-derived macrophages enhance stemness of lung adenocarcinoma A549 cells. Ann. Transl. Med. 2021, 9, 709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.; Young, H.; Hurlstone, A.; Wellbrock, C. Differentiation of THP1 Cells into Macrophages for Transwell Co-culture Assay with Melanoma Cells. Bio-Protocol 2015, 5, e1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazan, A.; Marusiak, A.A. Protocols for Co-Culture Phenotypic Assays with Breast Cancer Cells and THP-1-Derived Macrophages. J. Mammary Gland. Biol. Neoplasia 2024, 29, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lund, M.E.; To, J.; O’BRien, B.A.; Donnelly, S. The choice of phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate differentiation protocol influences the response of THP-1 macrophages to a pro-inflammatory stimulus. J. Immunol. Methods 2016, 430, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, E.K.; Jung, H.S.; Yang, H.I.; Yoo, M.C.; Kim, C.; Kim, K.S. Optimized THP-1 differentiation is required for the detection of responses to weak stimuli. Inflamm Res. 2007, 56, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estrella, J.L.; Kan-Sutton, C.; Gong, X.; Rajagopalan, M.; Lewis, D.E.; Hunter, R.L.; Eissa, N.T.; Jagannath, C. A Novel in vitro Human Macrophage Model to Study the Persistence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis Using Vitamin D3 and Retinoic Acid Activated THP-1 Macrophages. Front. Microbiol. 2011, 2, 7609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daigneault, M.; Preston, J.A.; Marriott, H.M.; Whyte, M.K.B.; Dockrell, D.H. The Identification of Markers of Macrophage Differentiation in PMA-Stimulated THP-1 Cells and Monocyte-Derived Macrophages. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e8668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solberg, R.; Smith, R.; Almlöf, M.; Tewolde, E.; Nilsen, H.; Johansen, H.T. Legumain expression, activity and secretion are increased during monocyte-to-macrophage differentiation and inhibited by atorvastatin. Biol. Chem. 2015, 396, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, E.; Graham, A.; Re, N.; Carr, I.; Robinson, J.; Mackie, S.; Morgan, A. Standardized protocols for differentiation of THP-1 cells to macrophages with distinct M(IFNγ+LPS), M(IL-4) and M(IL-10) phenotypes. J. Immunol. Methods 2020, 478, 112721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeß, M.B.; Wittig, B.; Cignarella, A.; Lorkowski, S. Reduced PMA enhances the responsiveness of transfected THP-1 macrophages to polarizing stimuli. J. Immunol. Methods 2014, 402, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stříž, I.; Slavčev, A.; Kalanin, J.; Jarešová, M.; Rennard, S.I. Cell–Cell Contacts with Epithelial Cells Modulate the Phenotype of Human Macrophages. Inflammation 2001, 25, 241–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Hernández, F.J. Cell Surface Area to Volume Relationship During Apoptosis and Apoptotic Body Formation. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 55, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, C.-S.; Tae, J.; Lee, Y.-M.; Kim, B.-S.; Moon, W.-S.; Kim, D.-K. Protease-activated Receptor 2 is Associated with Activation of Human Macrophage Cell Line THP-1. Immune Netw. 2005, 5, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sridharan, R.; Cavanagh, B.; Cameron, A.R.; Kelly, D.J.; O’BRien, F.J. Material stiffness influences the polarization state, function and migration mode of macrophages. Acta Biomater. 2019, 89, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlier, F.M.; de Fays, C.; Pilette, C. Epithelial Barrier Dysfunction in Chronic Respiratory Diseases. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 691227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wittekindt, O.H. Tight junctions in pulmonary epithelia during lung inflammation. Pflüg. Arch. Eur. J. Physiol. 2017, 469, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colvin, V.C.; Bramer, L.M.; Rivera, B.N.; Pennington, J.M.; Waters, K.M.; Tilton, S.C. Modeling PAH Mixture Interactions in a Human In Vitro Organotypic Respiratory Model. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 4326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Lin, Y.; Chen, R.; Yu, H.; Li, Y.; Chen, M.; Dou, C.; Yin, P.; Zhang, L.; Tang, P. Ghost messages: Cell death signals spread. Cell Commun. Signal. 2023, 21, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melzi, G.; van Triel, J.; Durand, E.; Crayford, A.; Ortega, I.K.; Barrellon-Vernay, R.; Duistermaat, E.; Delhaye, D.; Focsa, C.; Boom, D.H.; et al. Toxicological evaluation of primary particulate matter emitted from combustion of aviation fuel. Chemosphere 2024, 363, 142958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Zou, H.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Du, Y.; Liu, J.; Huang, Z.; Liang, L.; Xie, R.; Yang, Q. Acute cytotoxicity test of PM2.5, NNK and BPDE in human normal bronchial epithelial cells: A comparison of a co-culture model containing macrophages and a mono-culture model. Toxicol. Vitr. 2022, 85, 105480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruysseveldt, E.; Martens, K.; Steelant, B. Airway Basal Cells, Protectors of Epithelial Walls in Health and Respiratory Diseases. Front. Allergy 2021, 2, 787128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loret, T.; Peyret, E.; Dubreuil, M.; Aguerre-Chariol, O.; Bressot, C.; le Bihan, O.; Amodeo, T.; Trouiller, B.; Braun, A.; Egles, C.; et al. Air-liquid interface exposure to aerosols of poorly soluble nanomaterials induces different biological activation levels compared to exposure to suspensions. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2016, 13, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, J.-H.; Bruse, S.; Liu, Y.; Duffy, V.; Zhang, C.; Oyamada, N.; Randell, S.; Matsumoto, A.; Thompson, D.C.; Lin, Y.; et al. Aldehyde dehydrogenase 3A1 protects airway epithelial cells from cigarette smoke-induced DNA damage and cytotoxicity. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2014, 68, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, S.; Lim, L.; Ki, Y.-J.; Choi, D.-H.; Song, H. Oxidative stress generated by polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons from ambient particulate matter enhance vascular smooth muscle cell migration through MMP upregulation and actin reorganization. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2022, 19, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, A.C.; Sumagin, R.; Rankin, C.R.; Leoni, G.; Mina, M.J.; Reiter, D.M.; Stehle, T.; Dermody, T.S.; Schaefer, S.A.; Hall, R.A.; et al. JAM-A associates with ZO-2, afadin, and PDZ-GEF1 to activate Rap2c and regulate epithelial barrier function. Mol. Biol. Cell 2013, 24, 2849–2860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamura, S.; Pasang, C.E.T.; Tsuda, M.; Ma, S.; Shindo, H.; Nagaoka, N.; Ohkubo, T.; Fujiyama, Y.; Tamai, M.; Tagawa, Y.-I. Tri-culture model of intestinal epithelial cell, macrophage, and bacteria for the triggering of inflammatory bowel disease on a microfluidic device. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 2025, 104, 151495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spalinger, M.R.; Sayoc-Becerra, A.; Santos, A.N.; Shawki, A.; Canale, V.; Krishnan, M.; Niechcial, A.; Obialo, N.; Scharl, M.; Li, J.; et al. PTPN2 Regulates Interactions Between Macrophages and Intestinal Epithelial Cells to Promote Intestinal Barrier Function. Gastroenterology 2020, 159, 1763–1777.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghisalberti, C.A.; Borzì, R.M.; Cetrullo, S.; Flamigni, F.; Cairo, G. Soft TCPTP Agonism—Novel Target to Rescue Airway Epithelial Integrity by Exogenous Spermidine. Front. Pharmacol. 2016, 7, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Xiong, Y.; Tu, J.; Tang, B.; Zhang, Z.; Yu, J.; Shen, L.; Luo, Q.; Ye, J. Hypoxia disrupts the nasal epithelial barrier by inhibiting PTPN2 in chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2023, 118, 110054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Zhu, Y.S.; Xu, H.; Sun, Y.; Li, Q.F. Inflammatory stimulation and hypoxia cooperatively activate HIF-1α in bronchial epithelial cells: Involvement of PI3K and NF-κB. Am. J. Physiol. Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2010, 298, L660–L669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prytherch, Z.; Job, C.; Marshall, H.; Oreffo, V.; Foster, M.; Bérubé, K. Tissue-Specific Stem Cell Differentiation in an in vitro Airway Model. Macromol. Biosci. 2011, 11, 1467–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakor, A.S.; Paulmurugan, R.; Kempen, P.; Zavaleta, C.; Sinclair, R.; Massoud, T.F.; Gambhir, S.S. Oxidative Stress Mediates the Effects of Raman-Active Gold Nanoparticles in Human Cells. Small 2011, 7, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betancur, D.; Munoz, C.; Onate, A. Expression of Macrophage Polarization Markers against the Most Prevalent Serotypes of Aggregatibacter actinomycetemomitans. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Burns, K.S.; Biggerstaff, A.G.; Pennington, J.M.; Tilton, S.C. Co-Culture of Primary Human Bronchial Epithelial Cells at the Air–Liquid Interface and THP-1 Macrophages to Investigate the Toxicity of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons. Toxics 2025, 13, 1065. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121065

Burns KS, Biggerstaff AG, Pennington JM, Tilton SC. Co-Culture of Primary Human Bronchial Epithelial Cells at the Air–Liquid Interface and THP-1 Macrophages to Investigate the Toxicity of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons. Toxics. 2025; 13(12):1065. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121065

Chicago/Turabian StyleBurns, Kyle S., Audrey G. Biggerstaff, Jamie M. Pennington, and Susan C. Tilton. 2025. "Co-Culture of Primary Human Bronchial Epithelial Cells at the Air–Liquid Interface and THP-1 Macrophages to Investigate the Toxicity of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons" Toxics 13, no. 12: 1065. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121065

APA StyleBurns, K. S., Biggerstaff, A. G., Pennington, J. M., & Tilton, S. C. (2025). Co-Culture of Primary Human Bronchial Epithelial Cells at the Air–Liquid Interface and THP-1 Macrophages to Investigate the Toxicity of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons. Toxics, 13(12), 1065. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121065