Understanding Target-Specific Effects of Antidepressant Drug Pollution on Molluscs: A Systematic Review Report

Abstract

1. Introduction

Objectives of the Review

- Populations—all species of aquatic molluscs;

- Exposure—laboratory-based water-born antidepressants (or their major pharmacologically active metabolites) singly administered;

- Comparator—naive (or vehicle solvent) control;

2. Methods

2.1. Deviation from the Systematic Review Protocol

2.2. Search Strategy, Article Screening and Critical Appraisal

2.3. Data Extraction, Potential Effect Modifiers and Synthesis

2.4. Evidence Synthesis

3. Results

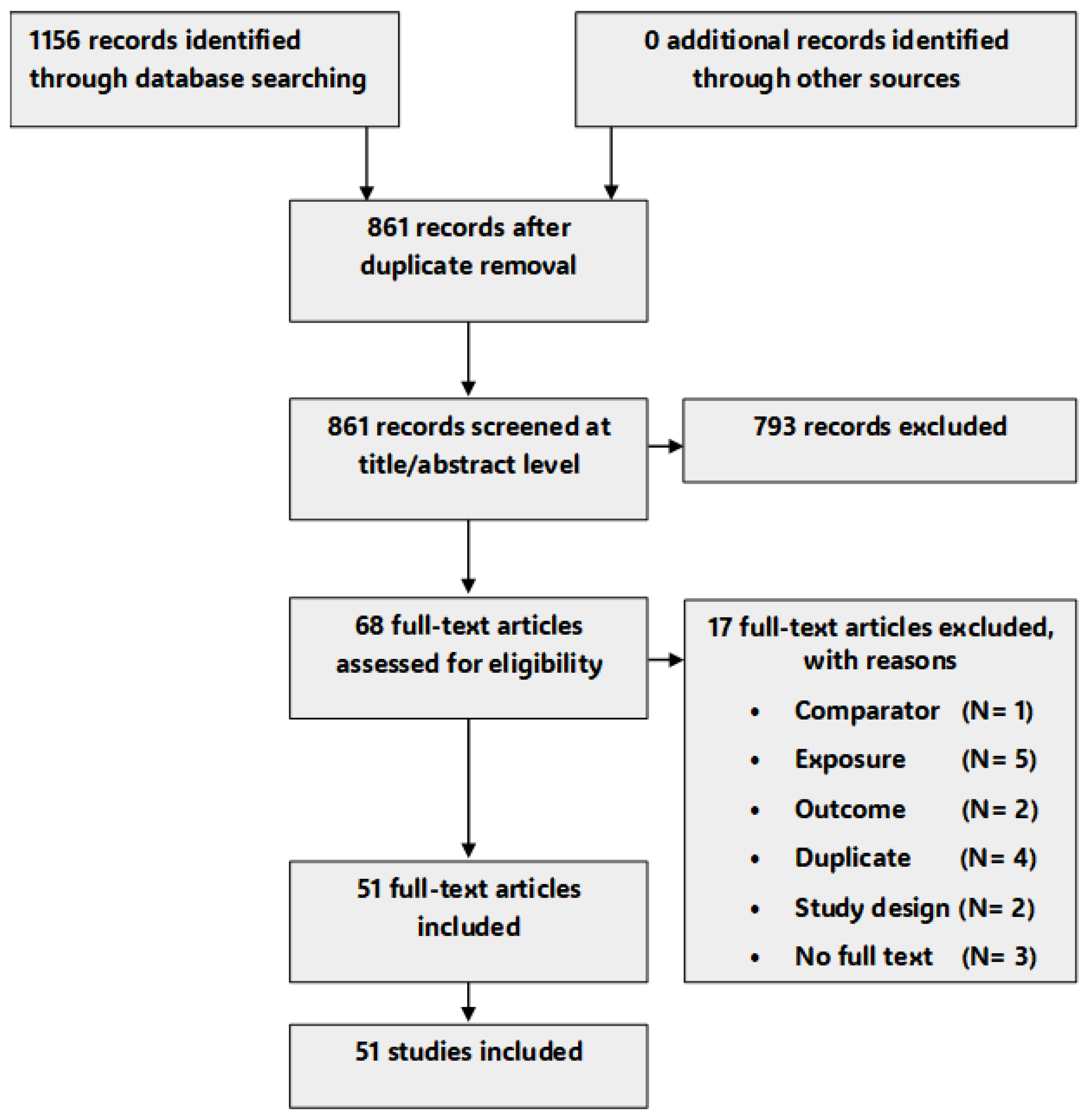

3.1. Study Selection

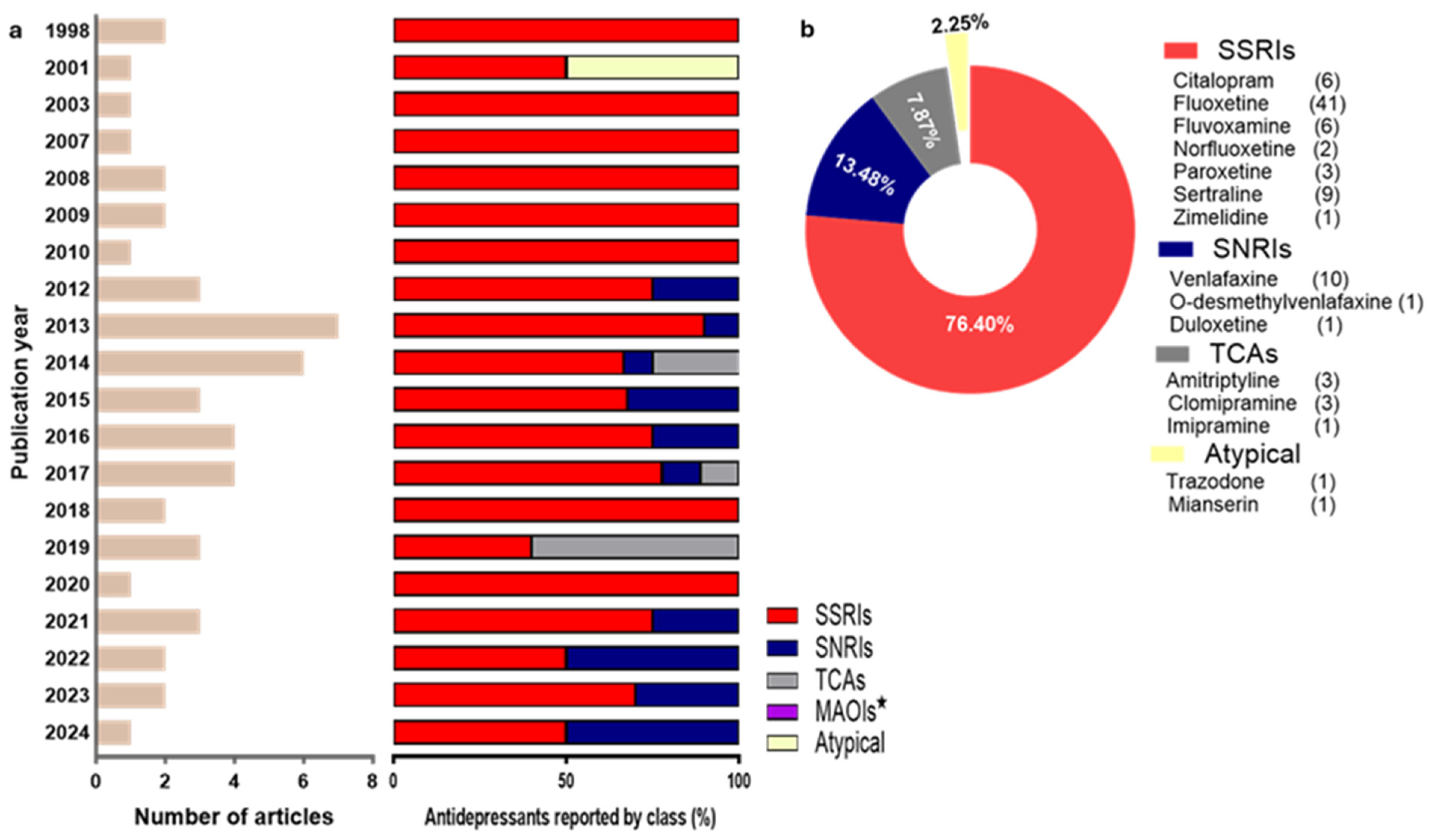

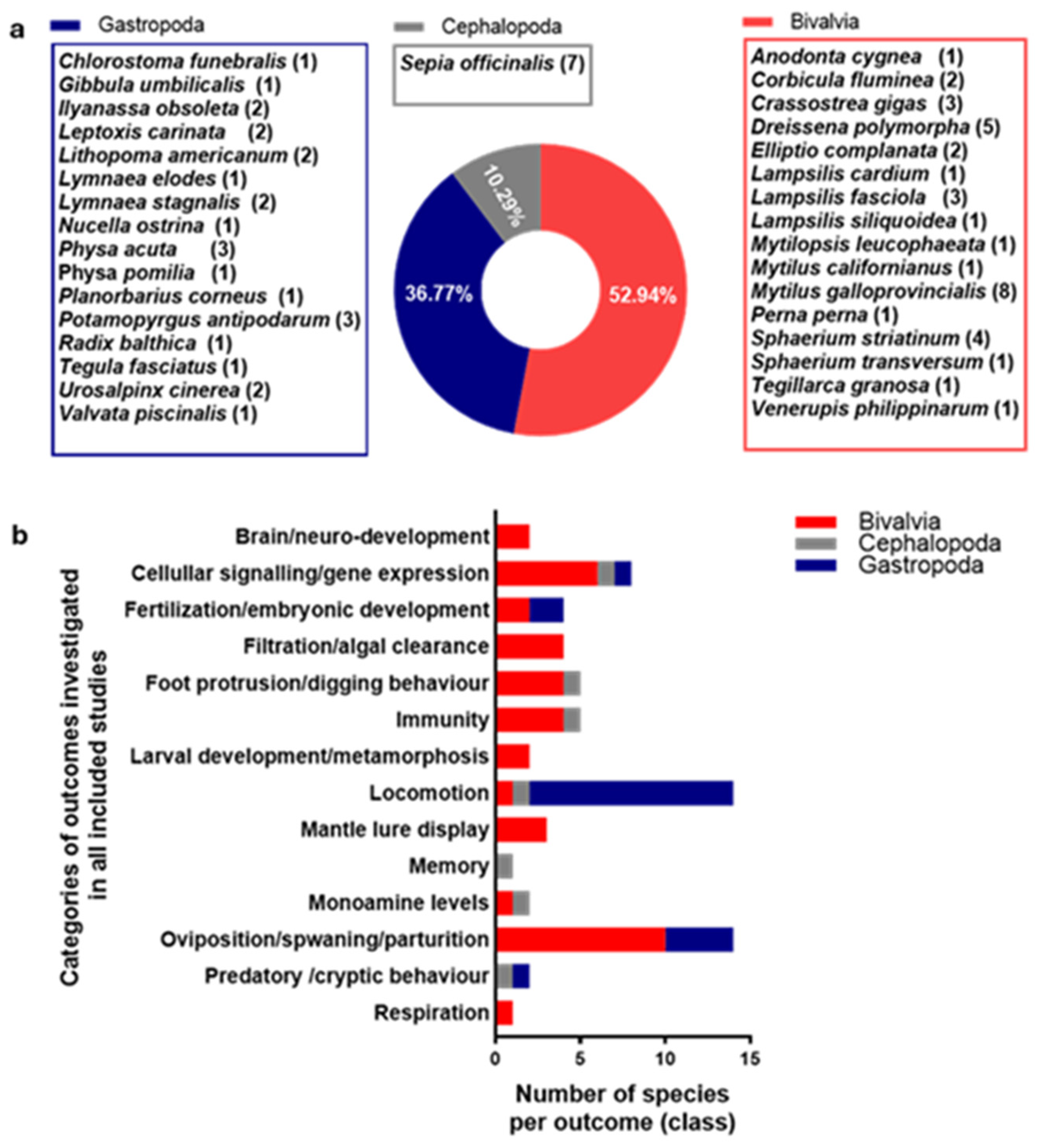

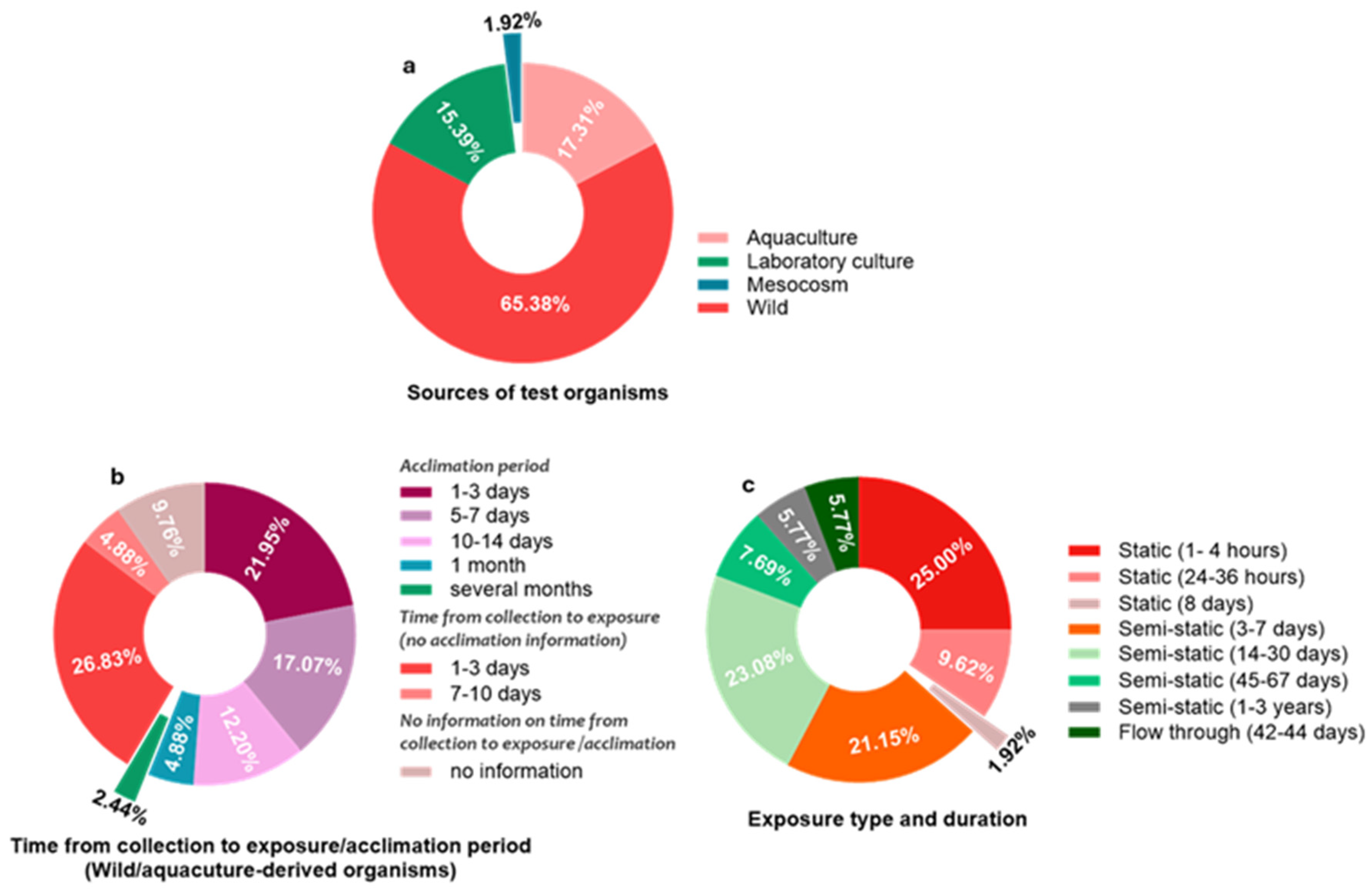

3.2. Characteristics of Included Studies

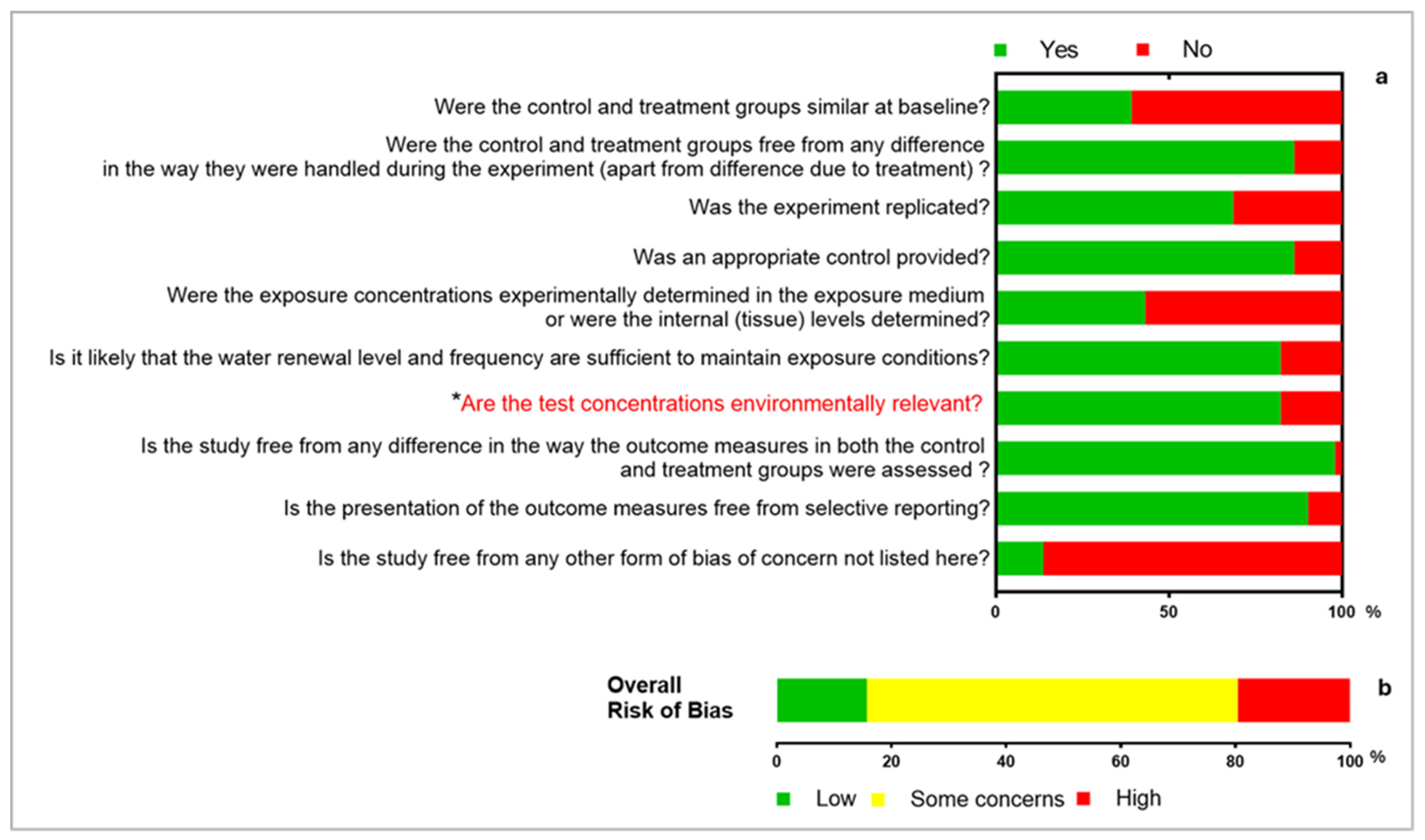

3.3. Critical Appraisal

3.4. Reported Outcomes and the Range of Evidence Across All Studies for Each Outcome

4. Discussion

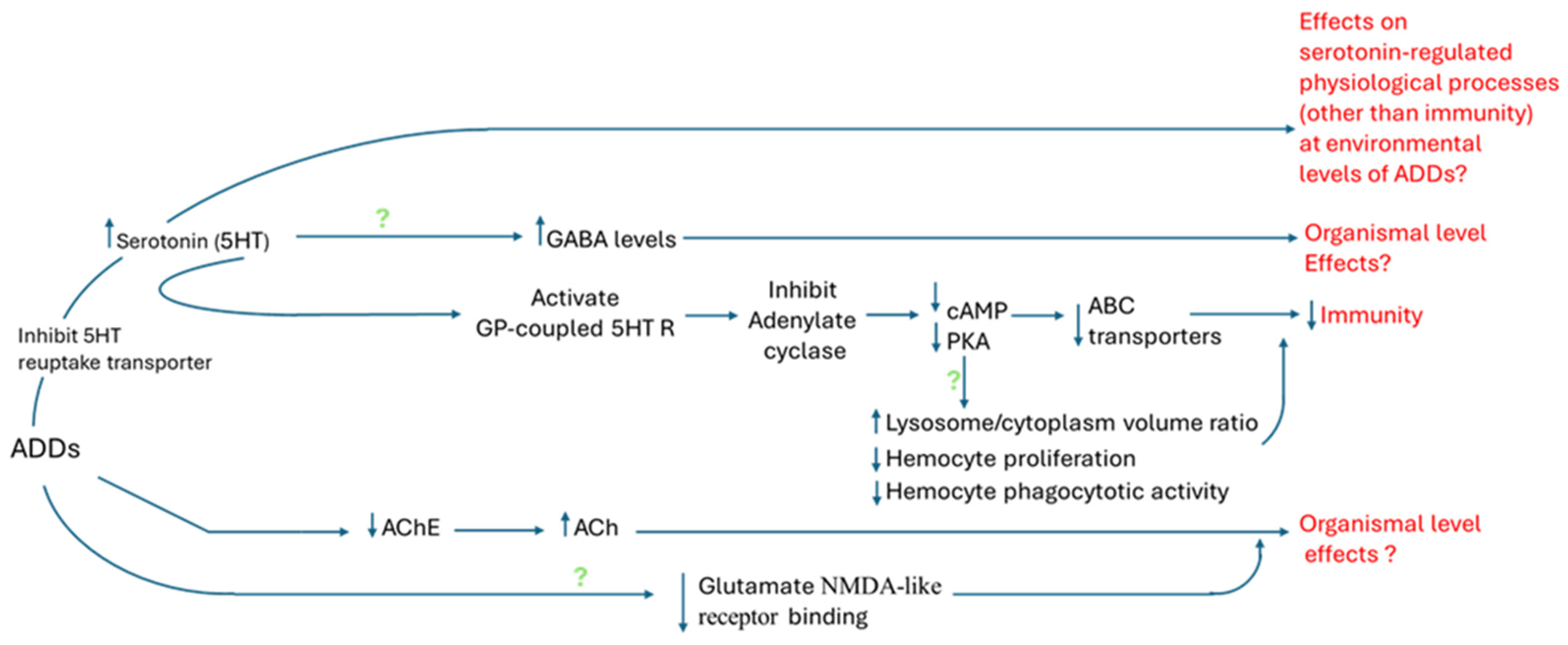

4.1. Effects of ADDs on Monoamine Neurotransmission

4.2. Effects of ADDs on Other Neurotransmitter Pathways

4.3. Effects of ADDs on (Loco)Motor Activities

- L. americanum exposed to fluvoxamine (induced at 43.4 and 434 µg/L, and 4.34 mg/L, but not 4.34 ng/L and 21.7 µg/L), fluoxetine (3.45 mg/L, but not 34.5 and 345 µg/L), citalopram (405 µg/L, but not 4.05 and 40.5 µg/L) and venlafaxine (313 µg/L, but not 3.13 and 31.3 µg/L);

- C. funebralis exposed to fluvoxamine (induced at 217 and 434 µg/L, and 4.3 mg/L, but not 43.4 µg/L), fluoxetine (345 µg/L and 3.45 mg/L, but not 34.5 µg/L), citalopram (2.03 and 4.05 mg/L, but not 40.5 and 405 µg/L) and venlafaxine (157 and 313 µg/L, and 3.13 mg/L, but not 3.13 and 31.3 µg/L);

- T. fasciatus exposed to fluvoxamine (induced at 434 µg/L and 4.34 mg/L, but not 43.4 µg/L), fluoxetine (345 µg/L and 3.45 mg/L, but not 3.45 and 34.5 µg/L), citalopram (405 µg/L, but not 4.05 and 40.5 µg/L) and venlafaxine (313 µg/L, but not 3.13 and 31.3 µg/L);

- U. cinerea exposed to fluvoxamine (induced at 434 and 868 µg/L, and 2.17 and 4.34 mg/L, but not 43.4 µg/L), fluoxetine (3.45 mg/L, but not 34.5 and 345 µg/L), citalopram (not induced at all at 4.05, 40.5 and 405 µg/L, and 4.05 mg/L) and venlafaxine (3.13 mg/L, but not 3.13, 31.3 and 313 µg/L);

- N. ostrina exposed to fluvoxamine (induced at 4.34 mg/L, but not 43.4 and 434 µg/L), fluoxetine (3.45 mg/L, but not 34.5 and 345 µg/L), citalopram (4.05 mg/L, but not 40.5 and 405 µg/L) and venlafaxine (1.57 and 3.13 mg/L, but not 31.3 and 313 µg/L).

- L. carinata (from 313 pg/L venlafaxine and 405 pg/L citalopram; nominal, ID: 7);

- L. elodes (from 31.3 ng/L venlafaxine and 4.05 µg/L citalopram; nominal, ID: 7).

- 31.3 µg/L (nominal) venlafaxine in I. obsoleta (ID: 22; longer righting time);

- 31.3 µg/L (nominal) venlafaxine in U. cinerea (ID: 219; increased crawling speed);

- 31.3 µg/L (nominal) venlafaxine in L. americanum (ID: 219; number reaching air–water interface).

4.4. Effects of ADDs on Egg and Egg Mass Production

4.5. Effects of ADDs on Fertilization

4.6. Effects of ADDs on Internal Embryo Development

4.7. Effects of ADDs on Larval Parturition

4.8. Effects of ADDs on Post-Larval Development and Neonates

4.9. Effects of ADDs on Neurophysiology: Camouflage, Learning and Brain Cell Development in S. officinalis

5. Robustness of the Synthesis

6. Conclusions and Future Research Direction

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sanusi, I.O.; Olutona, G.O.; Wawata, I.G.; Onohuean, H. Occurrence, Environmental Impact and Fate of Pharmaceuticals in Groundwater and Surface Water: A Critical Review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 90595–90614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samal, K.; Mahapatra, S.; Hibzur Ali, M. Pharmaceutical Wastewater as Emerging Contaminants (EC): Treatment Technologies, Impact on Environment and Human Health. Energy Nexus 2022, 6, 100076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezzelani, M.; Gorbi, S.; Regoli, F. Pharmaceuticals in the Aquatic Environments: Evidence of Emerged Threat and Future Challenges for Marine Organisms. Mar. Environ. Res. 2018, 140, 41–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, J.L.; Boxall, A.B.A.; Kolpin, D.W.; Leung, K.M.Y.; Lai, R.W.S.; Galban-Malag, C.; Adell, A.D.; Mondon, J.; Metian, M.; Marchant, R.A.; et al. Pharmaceutical Pollution of the World’s Rivers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2113947119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McRobb, F.M.; Sahagún, V.; Kufareva, I.; Abagyan, R. In Silico Analysis of the Conservation of Human Toxicity and Endocrine Disruption Targets in Aquatic Species. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 1964–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huggett, D.B.; Cook, J.C.; Ericson, J.F.; Williams, R.T. A Theoretical Model for Utilizing Mammalian Pharmacology and Safety Data to Prioritize Potential Impacts of Human Pharmaceuticals to Fish. Hum. Ecol. Risk Assess. Int. J. 2003, 9, 1789–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacqué-cazenave, J.; Bharatiya, R.; Barrière, G.; Delbecque, J.P.; Bouguiyoud, N.; Di Giovanni, G.; Cattaert, D.; De Deurwaerdère, P. Serotonin in Animal Cognition and Behavior. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, K.M.; Schoenbaum, G. Dopamine. Curr. Biol. 2022, 32, R817–R824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tierney, A.J. Invertebrate Serotonin Receptors: A Molecular Perspective on Classification and Pharmacology. J. Exp. Biol. 2018, 221, jeb184838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caveney, S.; Cladman, W.; Verellen, L.A.; Donly, C. Ancestry of Neuronal Monoamine Transporters in the Metazoa. J. Exp. Biol. 2006, 209, 4858–4868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regenthal, R.; Krueger, M.; Koeppel, C.; Preiss, R. Drug Levels: Therapeutic and Toxic Serum/Plasma Concentrations of Common Drugs. J. Clin. Monit. Comput. 1999, 15, 529–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabaku, O.; Yang, A.; Tharmarajah, S.; Suda, K.; Vigod, S.; Tadrous, M. Global Trends in Antidepressant, Atypical Antipsychotic, and Benzodiazepine Use: A Cross-Sectional Analysis of 64 Countries. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0284389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naser, A.Y.; Alwafi, H.; Al-Daghastani, T.; Hemmo, S.I.; Alrawashdeh, H.M.; Jalal, Z.; Paudyal, V.; Alyamani, N.; Almaghrabi, M.; Shamieh, A. Drugs Utilization Profile in England and Wales in the Past 15 Years: A Secular Trend Analysis. BMC Prim. Care 2022, 23, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brody, D.J.; Gu, Q. Antidepressant Use Among Adults: United States, 2015–2018; NCHS Data Brief No 377; National Center for Health Statistics: Hyattsville, MD, USA, 2020; pp. 1–8.

- Deo, R.P. Pharmaceuticals in the Surface Water of the USA: A Review. Curr. Environ. Heal. Rep. 2014, 1, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, S.L.; Winter, M.J.; Norton, W.H.J.; Tyler, C.R. The Potential for Adverse Effects in Fish Exposed to Antidepressants in the Aquatic Environment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 16299–16312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemchem, M.; Chemchem, A.; Aydıner, B.; Seferoğlu, Z. Recent Advances in Colorimetric and Fluorometric Sensing of Neurotransmitters by Organic Scaffolds. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 244, 114820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, M.; Shibata, E.; Tohyama, K.; Kudo, K.; Endoh, J.; Otsuka, K.; Sakai, A. Monoamine Neurons in the Human Brain Stem: Anatomy, Magnetic Resonance Imaging Findings, and Clinical Implications. Neuroreport 2008, 19, 1649–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, R.Y.; Bloom, F.E. Central Catecholamine Neuron Systems: Anatomy and Physiology of the Norepinephrine and Epinephrine Systems. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 1979, 2, 113–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, M.; Gray, J.A.; Roth, B.L. The Expanded Biology of Serotonin. Annu. Rev. Med. 2009, 60, 355–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, G.E.; Gainetdinov, R.R.; Caron, M.G. Plasma Membrane Monoamine Transporters: Structure, Regulation and Function. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2003, 4, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, L.; Trovato, C.; Musumeci, S.A.; Catania, M.V.; Ciranna, L. 5-HT1A and 5-HT7 Receptors Differently Modulate AMPA Receptor-Mediated Hippocampal Synaptic Transmission. Hippocampus 2012, 22, 790–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortolato, M.; Chen, K.; Shih, J.C. Monoamine Oxidase Inactivation: From Pathophysiology to Therapeutics. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2008, 60, 1527–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, P.L. How Antidepressants Help Depression: Mechanisms of Action and Clinical Response. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2004, 65, 25–30. [Google Scholar]

- Marken, P.A.; Munro, S.J. Selecting a Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor: Clinically Important Distinguishing Features. Prim. Care Companion J. Clin. Psychiatry 2000, 2, 205–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, L.; Nutt, D. Anxiolytics. Psychiatry 2007, 6, 284–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Racagni, G.; Popoli, M. The Pharmacological Properties of Antidepressants. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2010, 25, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Kataoka, Y.; Ostinelli, E.G.; Cipriani, A.; Furukawa, T.A. National Prescription Patterns of Antidepressants in the Treatment of Adults With Major Depression in the US Between 1996 and 2015: A Population Representative Survey Based Analysis. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Global Burden of Mental Disorders and the Need for a Comprehensive, Coordinated Response from Health and Social Sectors at the Country Level; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, S.W.; Helmeste, D.M.; Leonard, B.E. Antidepressant Compounds: A Critical Review. In Depression: From Psychopathology to Pharmacotherapy; Karger: Berlin, Germany, 2010; Volume 27, pp. 1–19. ISBN 9783805596060. [Google Scholar]

- Hillhouse, T.M.; Porter, J.H. A Brief History of the Development of Antidepressant Drugs: From Monoamines to Glutamate. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2015, 23, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwasinger-Schmidt, T.E.; Macaluso, M. Other Antidepressants. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 2019, 250, 325–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stimmel, G.L.; Dopheide, J.A.; Stahl, S.M. Mirtazapine: An Antidepressant with Noradrenergic and Specific Serotonergic Effects. Pharmacother. J. Hum. Pharmacol. Drug Ther. 1997, 17, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhães, P.; Alves, G.; Llerena, A.; Falcão, A. Venlafaxine Pharmacokinetics Focused on Drug Metabolism and Potential Biomarkers. Drug Metabol. Drug Interact. 2014, 29, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudorfer, M.V.; Potter, W.Z. Metabolism of Tricyclic Antidepressants. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 1999, 19, 373–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakaraya, Z.; Abu Assab, M.; Tamimi, L.N.; Karameh, N.; Hailat, M.; Al-Omari, L.; Abu Dayyih, W.; Alasasfeh, O.; Awad, M.; Awad, R. Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics: A Comprehensive Analysis of the Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion of Psychiatric Drugs. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lajeunesse, A.; Smyth, S.A.; Barclay, K.; Sauvé, S.; Gagnon, C. Distribution of Antidepressant Residues in Wastewater and Biosolids Following Different Treatment Processes by Municipal Wastewater Treatment Plants in Canada. Water Res. 2012, 46, 5600–5612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metcalfe, C.D.; Chu, S.; Judt, C.; Li, H.; Oakes, K.D.; Servos, M.R.; Andrews, D.M. Antidepressants and Their Metabolites in Municipal Wastewater, and Downstream Exposure in an Urban Watershed. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2010, 29, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giebułtowicz, J.; Nałecz-Jawecki, G. Occurrence of Antidepressant Residues in the Sewage-Impacted Vistula and Utrata Rivers and in Tap Water in Warsaw (Poland). Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2014, 104, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, M.M.; Furlong, E.T. Trace Analysis of Antidepressant Pharmaceuticals and Their Select Degradates in Aquatic Matrixes by LC/ESI/MS/MS. Anal. Chem. 2008, 80, 1756–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.-D.; Li, J.; Li, J.-J.; Liu, M.; Yan, D.-Z.; Shi, W.-Y.; Xu, G. Occurrence and Source Analysis of Selected Antidepressants and Their Metabolites in Municipal Wastewater and Receiving Surface Water. Environ. Sci. Process. Impacts 2018, 20, 1020–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinney, C.A.; Furlong, E.T.; Werner, S.L.; Cahill, J.D. Presence and Distribution of Wastewater-Derived Pharmaceuticals in Soil Irrigated with Reclaimed Water. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2006, 25, 317–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richmond, E.K.; Rosi, E.J.; Walters, D.M.; Fick, J.; Hamilton, S.K.; Brodin, T.; Sundelin, A.; Grace, M.R. A Diverse Suite of Pharmaceuticals Contaminates Stream and Riparian Food Webs. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 4491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabicova, K.; Grabic, R.; Fedorova, G.; Fick, J.; Cerveny, D.; Kolarova, J.; Turek, J.; Zlabek, V.; Randak, T. Bioaccumulation of Psychoactive Pharmaceuticals in Fish in an Effluent Dominated Stream. Water Res. 2017, 124, 654–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, M.M.; Furlong, E.T.; Kolpin, D.W.; Werner, S.L.; Schoenfuss, H.L.; Barber, L.B.; Blazer, V.S.; Norris, D.O.; Vajda, A.M. Antidepressant Pharmaceuticals in Two U.S. Effluent-Impacted Streams: Occurrence and Fate in Water and Sediment and Selective Uptake in Fish Neural Tissue. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 1918–1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Zacarías, C.; Barocio, M.E.; Hidalgo-Vázquez, E.; Sosa-Hernández, J.E.; Parra-Arroyo, L.; López-Pacheco, I.Y.; Barceló, D.; Iqbal, H.N.M.; Parra-Saldívar, R. Antidepressant Drugs as Emerging Contaminants: Occurrence in Urban and Non-Urban Waters and Analytical Methods for Their Detection. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 757, 143722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreira, D.G.; Aires, A.; de Lourdes Pereira, M.; Oliveira, M. Levels and Effects of Antidepressant Drugs to Aquatic Organisms. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2022, 256, 109322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeoman, M.S.; Pieneman, A.W.; Ferguson, G.P.; Ter Maat, A.; Benjamin, P.R. Modulatory Role for the Serotonergic Cerebral Giant Cells in the Feeding System of the Snail, Lymnaea. I. Fine Wire Recording in the Intact Animal and Pharmacology. J. Neurophysiol. 1994, 72, 1357–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kupfermann, I.; Weiss, K.R. Activity of an Identified Serotonergic Neuron in Free Moving Aplysia Correlates with Behavioral Arousal. Brain Res. 1982, 241, 334–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeoman, M.S.; Brierley, M.J.; Benjamin, P.R. Central Pattern Generator Interneurons Are Targets for the Modulatory Serotonergic Cerebral Giant Cells in the Feeding System of Lymnaea. J. Neurophysiol. 1996, 75, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotsyuba, E.; Kalachev, A.; Kameneva, P.; Dyachuk, V. Distribution of Molecules Related to Neurotransmission in the Nervous System of the Mussel Crenomytilus Grayanus. Front. Neuroanat. 2020, 14, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meechonkit, P.; Kovitvadhi, U.; Chatchavalvanich, K.; Sretarugsa, P.; Weerachatyanukul, W. Localization of Serotonin in Neuronal Ganglia of the Freshwater Pearl Mussel, Hyriopsis (Hyriopsis) Bialata. J. Molluscan Stud. 2010, 76, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, D.M.; Deaton, L.; Shumway, S.E.; Holohan, B.A.; Ward, J.E. Modulation of Pumping Rate by Two Species of Marine Bivalve Molluscs in Response to Neurotransmitters: Comparison of in Vitro and in Vivo Results. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2015, 185, 150–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messenger, J.B. Neurotransmitters of Cephalopods. Invertebr. Neurosci. 1996, 2, 95–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krantic, S.; Dubé, F.; Guerrier, P. Evidence for a New Subtype of Serotonin Receptor in Oocytes of the Surf Clam Spisula Solidissima. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 1993, 90, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osada, M.; Nakata, A.; Matsumoto, T.; Mori, K. Pharmacological Characterization of Serotonin Receptor in the Oocyte Membrane of Bivalve Molluscs and Its Formation during Oogenesis. J. Exp. Zool. 1998, 281, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osada, M.; Nomura, T. Seasonal Variations of Catecholamine Levels in the TIssues of the Japanese Oyster, Crassostrea Gigas. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. 1989, 93, 171–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, G.; Rivera, A. Role of Monoamines in the Reproductive Process of Argopecten Purpuratus. Invertebr. Reprod. Dev. 1994, 25, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Sánchez, J.A.; Maeda-Martínez, A.N.; Croll, R.P.; Acosta-Salmón, H. Monoamine Fluctuations during the Reproductive Cycle of the Pacific Lion’s Paw Scallop Nodipecten Subnodosus. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2009, 154, 425–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridgham, J.T.; Keay, J.; Ortlund, E.A.; Thornton, J.W. Vestigialization of an Allosteric Switch: Genetic and Structural Mechanisms for the Evolution of Constitutive Activity in a Steroid Hormone Receptor. PLoS Genet. 2014, 10, e1004058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fodor, I.; Urbán, P.; Scott, A.P.; Pirger, Z. A Critical Evaluation of Some of the Recent So-Called ‘Evidence’ for the Involvement of Vertebrate-Type Sex Steroids in the Reproduction of Mollusks. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2020, 516, 110949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, F.; Han, X.; An, L.; Lei, K.; Qi, H.; LeBlanc, G.A. Freshwater Snail Parafossarulus Striatulus Estrogen Receptor: Characteristics and Expression Profiles under Lab and Field Exposure. Chemosphere 2019, 220, 611–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, S.; Baynes, A.; Lockyer, A.E.; Routledge, E.J.; Jones, C.S.; Noble, L.R.; Jobling, S. Steroid Androgen Exposure during Development Has No Effect on Reproductive Physiology of Biomphalaria Glabrata. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0159852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, S.; Jobling, S.; Jones, C.S.; Noble, L.R.; Routledge, E.J.; Lockyer, A.E. The Nuclear Receptors of Biomphalaria Glabrata and Lottia Gigantea:Implications for Developing New Model Organisms. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0121259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogeler, S.; Galloway, T.S.; Lyons, B.P.; Bean, T.P. The Nuclear Receptor Gene Family in the Pacific Oyster, Crassostrea Gigas, Contains a Novel Subfamily Group. BMC Genom. 2014, 15, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, J.P.; Yoshino, T.P. Monoamines in the Albumen Gland, Plasma, and Central Nervous System of the Snail Biomphalaria Glabrata during Egg-Laying. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2002, 132, 411–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukai, S.T.; Kiehn, L.; Saleuddin, A.S.M. Dopamine Stimulates Snail Albumen Gland Glycoprotein Secretion through the Activation of a D1-like Receptor. J. Exp. Biol. 2004, 207, 2507–2518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glebov, K.; Voronezhskaya, E.E.; Khabarova, M.Y.; Ivashkin, E.; Nezlin, L.P.; Ponimaskin, E.G. Mechanisms Underlying Dual Effects of Serotonin during Development of Helisoma Trivolvis (Mollusca). BMC Dev. Biol. 2014, 14, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Wang, L.; Yan, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Ge, W.; Li, M.; Wang, W.; Song, X.; Song, L. D1 Dopamine Receptor Is Involved in Shell Formation in Larvae of Pacific Oyster Crassostrea Gigas. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2018, 84, 337–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, L.; Song, X.; Wang, W.; Zheng, Y.; Zong, Y.; Lv, Z.; Song, L. Ocean Acidification Inhibits Initial Shell Formation of Oyster Larvae by Suppressing the Biosynthesis of Serotonin and Dopamine. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 735, 139469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanninger, A.; Wollesen, T. The Evolution of Molluscs. Biol. Rev. 2019, 94, 102–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2022. In Towards Blue Transformation; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2022; ISBN 978-92-5-136364-5. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd, C.E.; McNevin, A.A.; Davis, R.P. The Contribution of Fisheries and Aquaculture to the Global Protein Supply. Food Secur. 2022, 14, 805–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandian, T.J. Reproduction and Development in Mollusca; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018; ISBN 9781351779654. [Google Scholar]

- Werkman, T.R.; De Vlieger, T.A.; Stoof, J.C. Indications for a Hormonal Function of Dopamine in the Central Nervous System of the Snail Lymnaea Stagnalis. Neurosci. Lett. 1990, 108, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werkman, T.R.; van Minnen, J.; Voorn, P.; Steinbusch, H.W.M.; Westerink, B.H.C.; De Vlieger, T.A.; Stoof, J.C. Localization of Dopamine and Its Relation to the Growth Hormone Producing Cells in the Central Nervous System of the Snail Lymnaea Stagnalis. Exp. Brain Res. 1991, 85, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, P.K.; Bourgeois, J.G.; Bueding, E. 5-Hydroxytryptamine and Dopamine in Biomphalaria Glabrata. J. Parasitol. 1974, 60, 264–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, N.; Vallejo, D.; Miller, M.W. Localization of Serotonin in the Nervous System of Biomphalaria Glabrata, an Intermediate Host for Schistosomiasis. J. Comp. Neurol. 2012, 520, 3236–3255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponder, W.F.; Lindberg, D.R.; Ponder, J.M. Biology and Evolution of the Mollusca, 1st ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2019; ISBN 9781351115667. [Google Scholar]

- Hartenstein, V. The Neuroendocrine System of Invertebrates: A Developmental and Evolutionary Perspective. J. Endocrinol. 2006, 190, 555–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloley, B.D. Metabolism of Monoamines in Invertebrates: The Relative Importance of Monoamine Oxidase in Different Phyla. Neurotoxicology 2004, 25, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blais, V.; Bounif, N.; Dubé, F. Characterization of a Novel Octopamine Receptor Expressed in the Surf Clam Spisula Solidissima. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2010, 167, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, D.; Li, Z.; Du, Y.; He, S.; Dong, Z.; Li, J. Identification of a Dopamine Receptor in Sinonovacula Constricta and Its Antioxidant Responses. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2020, 103, 103512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugamori, K.S.; Sunahara, R.K.; Guan, H.C.; Bulloch, A.G.M.; Tensen, C.P.; Seeman, P.; Niznik, H.B.; Van Tol, H.H.M. Serotonin Receptor CDNA Cloned from Lymnaea Stagnalis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1993, 90, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edsinger, E.; Dölen, G. A Conserved Role for Serotonergic Neurotransmission in Mediating Social Behavior in Octopus. Curr. Biol. 2018, 28, 3136–3142.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rafiq, A.; Capolupo, M.; Addesse, G.; Valbonesi, P.; Fabbri, E. Antidepressants and Their Metabolites Primarily Affect Lysosomal Functions in the Marine Mussel, Mytilus Galloprovincialis. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 903, 166078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magni, S.; Parolini, M.; Della Torre, C.; de Oliveira, L.F.; Catani, M.; Guzzinati, R.; Cavazzini, A.; Binelli, A. Multi-Biomarker Investigation to Assess Toxicity Induced by Two Antidepressants on Dreissena Polymorpha. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 578, 452–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imiuwa, M.E.; Baynes, A.; Kanda, R.; Routledge, E.J. Environmentally Relevant Concentrations of the Tricyclic Antidepressant, Amitriptyline, Affect Feeding and Reproduction in a Freshwater Mollusc. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 281, 116656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, P.P.; Ford, A.T. The Biological Effects of Antidepressants on the Molluscs and Crustaceans: A Review. Aquat. Toxicol. 2014, 151, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, A.T.; Fong, P.P. The Effects of Antidepressants Appear to Be Rapid and at Environmentally Relevant Concentrations. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2016, 35, 794–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, L.J.G.; Pereira, A.M.P.T.; Meisel, L.M.; Lino, C.M.; Pena, A. Reviewing the Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) Footprint in the Aquatic Biota: Uptake, Bioaccumulation and Ecotoxicology. Environ. Pollut. 2015, 197, 127–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canesi, L.; Miglioli, A.; Balbi, T.; Fabbri, E. Physiological Roles of Serotonin in Bivalves: Possible Interference by Environmental Chemicals Resulting in Neuroendocrine Disruption. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 792589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sehonova, P.; Svobodova, Z.; Dolezelova, P.; Vosmerova, P.; Faggio, C. Effects of Waterborne Antidepressants on Non-Target Animals Living in the Aquatic Environment: A Review. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 631–632, 789–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elliott, C.J.H.; Susswein, A.J. Comparative Neuroethology of Feeding Control in Molluscs. J. Exp. Biol. 2002, 205, 877–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernádi, L.; Kárpáti, L.; Gyori, J.; Vehovszky, Á.; Hiripi, L. Humoral Serotonin and Dopamine Modulate the Feeding in the Snail, Helix Pomatia. Acta Biol. Hung. 2008, 59, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lukowiak, K.; Martens, K.; Orr, M.; Parvez, K.; Rosenegger, D.; Sangha, S. Modulation of Aerial Respiratory Behaviour in a Pond Snail. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 2006, 154, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, Z.; Lee, T.K.M.; Inoue, T.; Luk, C.; Hasan, S.U.; Lukowiak, K.; Syed, N.I. An Identified Central Pattern-Generating Neuron Co-Ordinates Sensory-Motor Components of Respiratory Behavior in Lymnaea. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2006, 23, 94–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newcomb, J.M.; Katz, P.S. Different Functions for Homologous Serotonergic Interneurons and Serotonin in Species-Specific Rhythmic Behaviours. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2009, 276, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlova, G.A. Effects of Serotonin, Dopamine and Ergometrine on Locomotion in the Pulmonate Mollusc Helix Lucorum. J. Exp. Biol. 2001, 204, 1625–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roshchin, M.; Balaban, P.M. Neural Control of Olfaction and Tentacle Movements by Serotonin and Dopamine in Terrestrial Snail. J. Comp. Physiol. A Neuroethol. Sens. Neural Behav. Physiol. 2012, 198, 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiger, W.A. Serotonergic Modulation of Behaviour: A Phylogenetic Overview. Biol. Rev. 1997, 72, 61–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filla, A.; Hiripi, L.; Elekes, K. Role of Aminergic (Serotonin and Dopamine) Systems in the Embryogenesis and Different Embryonic Behaviors of the Pond Snail, Lymnaea Stagnalis. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2009, 149, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, Y.; Yang, B.; Dong, W.; Liu, Z.; Lv, Z.; Jia, Z.; Qiu, L.; Wang, L.; Song, L. A Serotonin Receptor (Cg5-HTR-1) Mediating Immune Response in Oyster Crassostrea Gigas. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2018, 82, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imiuwa, M.E.; Baynes, A.; Routledge, E.J. Understanding Target-Specific Effects of Antidepressant Drug Pollution on Molluscs: A Systematic Review Protocol. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0287582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohl, C.; McIntosh, E.J.; Unger, S.; Haddaway, N.R.; Kecke, S.; Schiemann, J.; Wilhelm, R. Online Tools Supporting the Conduct and Reporting of Systematic Reviews and Systematic Maps: A Case Study on CADIMA and Review of Existing Tools. Environ. Evid. 2018, 7, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowie, K.; Rahmatullah, A.; Hardy, N.; Holub, K.; Kallmes, K. Web-Based Software Tools for Systematic Literature Review in Medicine: Systematic Search and Feature Analysis. JMIR Med. Inform. 2022, 10, e33219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazelton, P.D.; Cope, W.G.; Mosher, S.; Pandolfo, T.J.; Belden, J.B.; Barnhart, M.C.; Bringolf, R.B. Fluoxetine Alters Adult Freshwater Mussel Behavior and Larval Metamorphosis. Sci. Total Environ. 2013, 445–446, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzellitti, S.; Fabbri, E. Cyclic-AMP Mediated Regulation of ABCB MRNA Expression in Mussel Haemocytes. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e61634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Poi, C.; Evariste, L.; Séguin, A.; Mottier, A.; Pedelucq, J.; Lebel, J.M.; Serpentini, A.; Budzinski, H.; Costil, K. Sub-Chronic Exposure to Fluoxetine in Juvenile Oysters (Crassostrea gigas): Uptake and Biological Effects. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 5002–5018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilroy, È.A.M.; Gillis, P.L.; King, L.E.; Bendo, N.A.; Salerno, J.; Giacomin, M.; de Solla, S.R. The Effects of Pharmaceuticals on a Unionid Mussel (Lampsilis siliquoidea): An Examination of Acute and Chronic Endpoints of Toxicity across Life Stages. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2017, 36, 1572–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raman, N.V.; Dubey, A.; van Donk, E.; von Elert, E.; Lürling, M.; Fernandes, T.V.; de Senerpont Domis, L.N. Understanding the Differential Impacts of Two Antidepressants on Locomotion of Freshwater Snails (Lymnaea stagnalis). Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 12406–12421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zha, J.; Yuan, L.; Wang, Z. Effects of Fluoxetine on Behavior, Antioxidant Enzyme Systems, and Multixenobiotic Resistance in the Asian Clam Corbicula Fluminea. Chemosphere 2015, 119, 856–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez Bueno, M.J.; Agüera, A.; Gómez, M.J.; Hernando, M.D.; García-Reyes, J.F.; Fernández-Alba, A.R. Application of Liquid Chromatography/Quadrupole-Linear Ion Trap Mass Spectrometry and Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry to the Determination of Pharmaceuticals and Related Contaminants in Wastewater. Anal. Chem. 2007, 79, 9372–9384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEachran, A.D.; Hedgespeth, M.L.; Newton, S.R.; McMahen, R.; Strynar, M.; Shea, D.; Nichols, E.G. Comparison of Emerging Contaminants in Receiving Waters Downstream of a Conventional Wastewater Treatment Plant and a Forest-Water Reuse System. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2018, 25, 12451–12463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidel, F.; Di Poi, C.; Imarazene, B.; Koueta, N.; Budzinski, H.; Van Delft, P.; Bellanger, C.; Jozet-Alves, C. Pre-Hatching Fluoxetine-Induced Neurochemical, Neurodevelopmental, and Immunological Changes in Newly Hatched Cuttlefish. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 5030–5045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, A.S.C.; Challis, J.K.; Ji, X.; Giesy, J.P.; Brinkmann, M. Impacts of Wastewater Effluents and Seasonal Trends on Levels of Antipsychotic Pharmaceuticals in Water and Sediments from Two Cold-Region Rivers. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 851, 158247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voloshenko-Rossin, A.; Gasser, G.; Cohen, K.; Gun, J.; Cumbal-Flores, L.; Parra-Morales, W.; Sarabia, F.; Ojeda, F.; Lev, O. Emerging Pollutants in the Esmeraldas Watershed in Ecuador: Discharge and Attenuation of Emerging Organic Pollutants along the San Pedro–Guayllabamba–Esmeraldas Rivers. Environ. Sci. Process. Impacts 2015, 17, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fick, J.; Söderström, H.; Lindberg, R.H.; Phan, C.; Tysklind, M.; Larsson, D.G.J. Contamination of Surface, Ground, and Drinking Water from Pharmaceutical Production. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2009, 28, 2522–2527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, M.; McKenzie, J.E.; Sowden, A.; Katikireddi, S.V.; Brennan, S.E.; Ellis, S.; Hartmann-Boyce, J.; Ryan, R.; Shepperd, S.; Thomas, J.; et al. Synthesis without Meta-Analysis (SWiM) in Systematic Reviews: Reporting Guideline. BMJ 2020, 368, l6890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, M.; Sowden, A.; Petticrew, M.; Arai, L.; Roberts, H.; Britten, N.; Popay, J. Testing Methodological Guidance on the Conduct of Narrative Synthesis in Systematic Reviews: Effectiveness of Interventions to Promote Smoke Alarm Ownership and Function. Evaluation 2009, 15, 49–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Detailed Review Paper (DRP) on Molluscs Life-Cycle Toxicity Testing; OECD: Paris, France, 2010; pp. 1–182. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. OECD Guideline for the Testing of Chemicals: Lymnaea Stagnalis Reproduction Test; OECD: Paris, France, 2016; pp. 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Rand-Weaver, M.; Margiotta-Casaluci, L.; Patel, A.; Panter, G.H.; Owen, S.F.; Sumpter, J.P. The Read-across Hypothesis and Environmental Risk Assessment of Pharmaceuticals. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 11384–11395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munari, M.; Marin, M.G.; Matozzo, V. Effects of the Antidepressant Fluoxetine on the Immune Parameters and Acetylcholinesterase Activity of the Clam Venerupis philippinarum. Mar. Environ. Res. 2014, 94, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, W.; Han, Y.; Sun, S.; Tang, Y.; Zhou, W.; Du, X.; Liu, G. Immunotoxicities of Microplastics and Sertraline, Alone and in Combination, to a Bivalve Species: Size-Dependent Interaction and Potential Toxication Mechanism. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 396, 122603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzellitti, S.; Buratti, S.; Capolupo, M.; Du, B.; Haddad, S.P.; Chambliss, C.K.; Brooks, B.W.; Fabbri, E. An Exploratory Investigation of Various Modes of Action and Potential Adverse Outcomes of Fluoxetine in Marine Mussels. Aquat. Toxicol. 2014, 151, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzellitti, S.; Buratti, S.; Valbonesi, P.; Fabbri, E. The Mode of Action (MOA) Approach Reveals Interactive Effects of Environmental Pharmaceuticals on Mytilus Galloprovincialis. Aquat. Toxicol. 2013, 140–141, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortez, F.S.; Souza, L.d.S.; Guimarães, L.L.; Pusceddu, F.H.; Maranho, L.A.; Fontes, M.K.; Moreno, B.B.; Nobre, C.R.; Abessa, D.M.d.S.; Cesar, A.; et al. Marine Contamination and Cytogenotoxic Effects of Fluoxetine in the Tropical Brown Mussel Perna Perna. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019, 141, 366–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Rey, M.; Bebianno, M.J. Does Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor (SSRI) Fluoxetine Affects Mussel Mytilus Galloprovincialis? Environ. Pollut. 2013, 173, 200–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidel, F.; Di Poi, C.; Budzinski, H.; Pardon, P.; Callewaert, W.; Arini, A.; Basu, N.; Dickel, L.; Bellanger, C.; Jozet-Alves, C. The Antidepressant Venlafaxine May Act as a Neurodevelopmental Toxicant in Cuttlefish (Sepia officinalis). Neurotoxicology 2016, 55, 142–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, G.; Gomez, E.; Dumas, T.; Rosain, D.; Mathieu, O.; Fenet, H.; Courant, F. Early Biological Modulations Resulting from 1-Week Venlafaxine Exposure of Marine Mussels Mytilus Galloprovincialis Determined by a Metabolomic Approach. Metabolites 2022, 12, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Poi, C.; Bidel, F.; Dickel, L.; Bellanger, C. Cryptic and Biochemical Responses of Young Cuttlefish Sepia Officinalis Exposed to Environmentally Relevant Concentrations of Fluoxetine. Aquat. Toxicol. 2014, 151, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, A.P. Do Mollusks Use Vertebrate Sex Steroids as Reproductive Hormones? II. Critical Review of the Evidence That Steroids Have Biological Effects. Steroids 2013, 78, 268–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fong, P.P.; Hoy, C.M. Antidepressants (Venlafaxine and Citalopram) Cause Foot Detachment from the Substrate in Freshwater Snails at Environmentally Relevant Concentrations. Mar. Freshw. Behav. Physiol. 2012, 45, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chabenat, A.; Knigge, T.; Bellanger, C. Antidepressants Modify Cryptic Behavior in Juvenile Cuttlefish at Environmentally Realistic Concentrations. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2021, 40, 2571–2577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chabenat, A.; Bidel, F.; Knigge, T.; Bellanger, C. Alteration of Predatory Behaviour and Growth in Juvenile Cuttlefish by Fluoxetine and Venlafaxine. Chemosphere 2021, 277, 130169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Poi, C.; Darmaillacq, A.S.; Dickel, L.; Boulouard, M.; Bellanger, C. Effects of Perinatal Exposure to Waterborne Fluoxetine on Memory Processing in the Cuttlefish Sepia Officinalis. Aquat. Toxicol. 2013, 132–133, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, P.P.; Blaszczyk, R.A.; Butler, M.G.; Stergio, J.W. Evidence That Bivalve Burrowing Is Mediated by Serotonin Receptors: Activation of Foot Inflation and Protrusion by Serotonin, Serotonergic Ligands and SSRI-Type Antidepressants in Three Species of Freshwater Bivalve. J. Molluscan Stud. 2023, 89, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, P.P.; Bury, T.B.S.; Donovan, E.E.; Lambert, O.J.; Palmucci, J.R.; Adamczak, S.K. Exposure to SSRI-Type Antidepressants Increases Righting Time in the Marine Snail Ilyanassa Obsoleta. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017, 24, 725–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chabenat, A.; Bellanger, C.; Jozet-Alves, C.; Knigge, T. Hidden in the Sand: Alteration of Burying Behaviour in Shore Crabs and Cuttlefish by Antidepressant Exposure. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2019, 186, 109738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nentwig, G. Effects of Pharmaceuticals on Aquatic Invertebrates. Part II: The Antidepressant Drug Fluoxetine. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2007, 52, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gust, M.; Buronfosse, T.; Giamberini, L.; Ramil, M.; Mons, R.; Garric, J. Effects of Fluoxetine on the Reproduction of Two Prosobranch Mollusks: Potamopyrgus Antipodarum and Valvata Piscinalis. Environ. Pollut. 2009, 157, 423–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Péry, A.R.R.; Gust, M.; Vollat, B.; Mons, R.; Ramil, M.; Fink, G.; Ternes, T.; Garric, J. Fluoxetine Effects Assessment on the Life Cycle of Aquatic Invertebrates. Chemosphere 2008, 73, 300–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, J.R.; Granek, E.F. Long-Term Exposure to Fluoxetine Reduces Growth and Reproductive Potential in the Dominant Rocky Intertidal Mussel, Mytilus Californianus. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 545–546, 621–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzellitti, S.; Buratti, S.; Du, B.; Haddad, S.P.; Chambliss, C.K.; Brooks, B.W.; Fabbri, E. A Multibiomarker Approach to Explore Interactive Effects of Propranolol and Fluoxetine in Marine Mussels. Environ. Pollut. 2015, 205, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bringolf, R.B.; Heltsley, R.M.; Newton, T.J.; Eads, C.B.; Fraley, S.J.; Shea, D.; Cope, W.G. Environmental Occurrence and Reproductive Effects of the Pharmaceutical Fluoxetine in Native Freshwater Mussels. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2010, 29, 1311–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna, T.O.; Plautz, S.C.; Salice, C.J. Effects of 17α-Ethynylestradiol, Fluoxetine, and the Mixture on Life History Traits and Population Growth Rates in a Freshwater Gastropod. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2013, 32, 2771–2778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, P.P.; Bury, T.B.; Dworkin-Brodsky, A.D.; Jasion, C.M.; Kell, R.C. The Antidepressants Venlafaxine (“Effexor”) and Fluoxetine (“Prozac”) Produce Different Effects on Locomotion in Two Species of Marine Snail, the Oyster Drill (Urosalpinx cinerea) and the Starsnail (Lithopoma americanum). Mar. Environ. Res. 2015, 103, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, J.; Brand, J.A.; Bai, Y.; Martin, J.M.; Wong, B.B.M.; Wlodkowic, D. Multi-Generational Impacts of Exposure to Antidepressant Fluoxetine on Behaviour, Reproduction, and Morphology of Freshwater Snail Physa Acuta. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 814, 152731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, M.; Eckstein, H.; Köhler, H.R.; Tisler, S.; Zwiener, C.; Triebskorn, R. Effects of the Antidepressants Citalopram and Venlafaxine on the Big Ramshorn Snail (Planorbarius corneus). Water 2021, 13, 1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estévez-Calvar, N.; Canesi, L.; Montagna, M.; Faimali, M.; Piazza, V.; Garaventa, F. Adverse Effects of the SSRI Antidepressant Sertraline on Early Life Stages of Marine Invertebrates. Mar. Environ. Res. 2017, 128, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Argüello, P.; Aparicio, N.; Fernández, C. Linking Embryo Toxicity with Genotoxic Responses in the Freshwater Snail Physa Acuta: Single Exposure to Benzo(a)Pyrene, Fluoxetine, Bisphenol A, Vinclozolin and Exposure to Binary Mixtures with Benzo(a)Pyrene. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2012, 80, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fong, P.P.; Philbert, C.M.; Roberts, B.J. Putative Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor-Induced Spawning and Parturition in Freshwater Bivalves Is Inhibited by Mammalian 5-HT2 Receptor Antagonists. J. Exp. Zool. A. Comp. Exp. Biol. 2003, 298, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunha, E.M.; Machado, J. Parturition in Anodonta Cygnea Induced by Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs). Can. J. Zool. 2001, 79, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, A.T.; Hyett, B.; Cassidy, D.; Malyon, G. The Effects of Fluoxetine on Attachment and Righting Behaviours in Marine (Gibbula unbilicalis) and Freshwater (Lymnea stagnalis) Gastropods. Ecotoxicology 2018, 27, 477–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, P.P.; DiPenta, K.E.; Jonik, S.M.; Ward, C.D. Short-Term Exposure to Tricyclic Antidepressants Delays Righting Time in Marine and Freshwater Snails with Evidence for Low-Dose Stimulation of Righting Speed by Imipramine. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 7840–7846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, P.P.; Molnar, N. Norfluoxetine Induces Spawning and Parturition in Estuarine and Freshwater Bivalves. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2008, 81, 535–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazelton, P.D.; Du, B.; Haddad, S.P.; Fritts, A.K.; Chambliss, C.K.; Brooks, B.W.; Bringolf, R.B. Chronic Fluoxetine Exposure Alters Movement and Burrowing in Adult Freshwater Mussels. Aquat. Toxicol. 2014, 151, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fong, P.P.; Molnar, N. Antidepressants Cause Foot Detachment from Substrate in Five Species of Marine Snail. Mar. Environ. Res. 2013, 84, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minguez, L.; Di Poi, C.; Farcy, E.; Ballandonne, C.; Benchouala, A.; Bojic, C.; Cossu-Leguille, C.; Costil, K.; Serpentini, A.; Lebel, J.M.; et al. Comparison of the Sensitivity of Seven Marine and Freshwater Bioassays as Regards Antidepressant Toxicity Assessment. Ecotoxicology 2014, 23, 1744–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, P.P. Zebra Mussel Spawning Is Induced in Low Concentrations of Putative Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors. Biol. Bull. 1998, 194, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazzara, R.; Blázquez, M.; Porte, C.; Barata, C. Low Environmental Levels of Fluoxetine Induce Spawning and Changes in Endogenous Estradiol Levels in the Zebra Mussel Dreissena Polymorpha. Aquat. Toxicol. 2012, 106–107, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hedgespeth, M.L.; Karasek, T.; Ahlgren, J.; Berglund, O.; Brönmark, C. Behaviour of Freshwater Snails (Radix Balthica) Exposed to the Pharmaceutical Sertraline under Simulated Predation Risk. Ecotoxicology 2018, 27, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, P.P.; Huminski, P.T.; D’Urso, L.M. Induction and Potentiation of Parturition in Fingernail Clams (Sphaerium Striatinum) by Selective Serotonin Re-Uptake Inhibitors (SSRIs). J. Exp. Zool. 1998, 280, 260–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-argüello, P.; Fernández, C.; Tarazona, J.V. Assessing the Effects of Fluoxetine on Physa Acuta (Gastropoda, Pulmonata) and Chironomus Riparius ( Insecta, Diptera) Using a Two-Species Water–Sediment Test. Sci. Total Environ. 2009, 407, 1937–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Poi, C.; Evariste, L.; Serpentini, A.; Halm-Lemeille, M.P.; Lebel, J.M.; Costil, K. Toxicity of Five Antidepressant Drugs on Embryo-Larval Development and Metamorphosis Success in the Pacific Oyster, Crassostrea gigas. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2014, 21, 13302–13314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornstein, S.G.; Schatzberg, A.F.; Thase, M.E.; Yonkers, K.A.; McCullough, J.P.; Keitner, G.I.; Gelenberg, A.J.; Davis, S.M.; Harrison, W.M.; Keller, M.B. Gender Differences in Treatment Response to Sertraline versus Imipramine in Chronic Depression. Am. J. Psychiatry 2000, 157, 1445–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juorio, A.V.; Killick, S.W. Monoamines and Their Metabolism in Some Molluscs. Comp. Gen. Pharmacol. 1972, 3, 283–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kime, D.E.; Messenger, J.B. Monoamines in the Cephalopod CNS: An HPLC Analysis. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part C Comp. Pharmacol. 1990, 96, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardales, J.R.; Hellman, U.; Villamarín, J.A. Identification of Multiple Isoforms of the CAMP-Dependent Protein Kinase Catalytic Subunit in the Bivalve Mollusc Mytilus Galloprovincialis. FEBS J. 2008, 275, 4479–4489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khannpnavar, B.; Mehta, V.; Qi, C.; Korkhov, V. Structure and Function of Adenylyl Cyclases, Key Enzymes in Cellular Signaling. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2020, 63, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.M.; Radzio-Andzelm, E.; Madhusudan; Akamine, P.; Taylor, S.S. The Catalytic Subunit of CAMP-Dependent Protein Kinase: Prototype for an Extended Network of Communication. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 1999, 71, 313–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, J.; Dormann, S.-M.G.; Martin-Facklam, M.; Kerpen, C.J.; Ketabi-Kiyanvash, N.; Haefeli, W.E. Inhibition of P-Glycoprotein by Newer Antidepressants. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2003, 305, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, M.; Zhou, N.; Cai, W.; Xu, H. Lysosomal Solute and Water Transport. J. Cell Biol. 2022, 221, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez, A.; Martinez, I.; Chung, A.; Berlot, C.H.; Andrews, N.W. CAMP Regulates Ca2+-Dependent Exocytosis of Lysosomes and Lysosome-Mediated Cell Invasion by Trypanosomes. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 16754–16759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, N.; Ramos-Espiritu, L.; Milner, T.A.; Buck, J.; Levin, L.R. Soluble Adenylyl Cyclase Is Essential for Proper Lysosomal Acidification. J. Gen. Physiol. 2016, 148, 325–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyne, V.E. The Importance of ATP in the Immune System of Molluscs Abstract Molluscs Rely on an Innate Immune System for Defence against Infection. Invading Organisms Are Phagocytosed by Circulating Hemocytes and Neutralised by a Combination of Hydrolytic Enzymes An. Invertebr. Surviv. J. 2011, 8, 48–55. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro, A.; Weißbach, S.; Faria, M.; Barata, C.; Piña, B.; Luckenbach, T. Abcb and Abcc Transporter Homologs Are Expressed and Active in Larvae and Adults of Zebra Mussel and Induced by Chemical Stress. Aquat. Toxicol. 2012, 122–123, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, T.C.; Rocha, J.B.T.; Morsch, V.M.; Neis, R.T.; Schetinger, M.R.C. Antidepressants Inhibit Human Acetylcholinesterase and Butyrylcholinesterase Activity. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2002, 1587, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhagwagar, Z.; Wylezinska, M.; Taylor, M.; Jezzard, P.; Matthews, P.M.; Phil, D.; Cowen, P.J. Administration of a Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor. Am. J. Psychiatry 2004, 161, 368–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musazzi, L.; Treccani, G.; Mallei, A.; Popoli, M. The Action of Antidepressants on the Glutamate System: Regulation of Glutamate Release and Glutamate Receptors. Biol. Psychiatry 2013, 73, 1180–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obara, K.; Mori, H.; Ihara, S.; Yoshioka, K.; Tanaka, Y. Inhibitory Actions of Antidepressants, Hypnotics, and Anxiolytics on Recombinant Human Acetylcholinesterase Activity. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2024, 47, 328–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellerbrock, I.; Sandström, A.; Tour, J.; Fanton, S.; Kadetoff, D.; Schalling, M.; Jensen, K.B.; Sitnikov, R.; Kosek, E. Serotonergic Gene-to-Gene Interaction Is Associated with Mood and GABA Concentrations but Not with Pain-Related Cerebral Processing in Fibromyalgia Subjects and Healthy Controls. Mol. Brain 2021, 14, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, E.J. Cholinergic Response in the Heart of the ClamMercenaria Mercenaria: Activation ByConus Californicus Venom Component. J. Comp. Physiol. A 1979, 129, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.W. GABA as a Neurotransmitter in Gastropod Molluscs. Biol. Bull. 2019, 236, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bone, Q.; Howarth, J.V. The Role of L-Glutamate in Neuromuscular Transmission in Some Molluscs. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. United Kingd. 1980, 60, 619–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, V.; Lengerer, B.; Wattiez, R.; Flammang, P. Molecular Insights into the Powerful Mucus-Based Adhesion of Limpets (Patella vulgata L.). Open Biol. 2020, 10, 200019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlova, G.A. The Similarity of Crawling Mechanisms in Aquatic and Terrestrial Gastropods. J. Comp. Physiol. A Neuroethol. Sens. Neural Behav. Physiol. 2019, 205, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mckenzie, J.D.; Caunce, M.; Hetherington, M.S.; Winlow, W. Serotonergic Innervation of the Foot of the Pond Snail Lymnaea stagnalis (L.). J. Neurocytol. 1998, 27, 459–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, M.A.; Catapane, E.J. The Nervous System Control of Lateral Ciliary Activity of the Gill of the Bivalve Mollusc, Crassostrea Virginica. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2007, 148, 445–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ram, J.L.; Moore, D.; Patchakayala, S.; Paredes, A.; Croll, R.P. Serotonergic Responses of the Siphons of the Zebra Mussel, Dreissena Polymorpha. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part C Pharmacol. Toxicol. Endocrinol. 1999, 124, 211–220. [Google Scholar]

- Honda, M.; Nishida, T.; Ono, H. Tricyclic Analogs Cyclobenzaprine, Amitriptyline and Cyproheptadine Inhibit the Spinal Reflex Transmission through 5-HT2 Receptors. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2003, 458, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanabe, T.; Yuan, Y.; Nakamura, S.; Itoh, N.; Takahashi, K.G.; Osada, M. The Role in Spawning of a Putative Serotonin Receptor Isolated from the Germ and Ciliary Cells of the Gonoduct in the Gonad of the Japanese Scallop, Patinopecten Yessoensis. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2010, 166, 620–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, P.P.; Wade, S.; Rostafin, M. Characterization of Serotonin Receptor Mediating Parturition in Fingernail ClamsSphaerium (Musculium) Spp. from Eastern North America. J. Exp. Zool. 1996, 275, 326–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krantic, S.; Guerrier, P.; Dubé, F. Meiosis Reinitiation in Surf Clam Oocytes Is Mediated via a 5-Hydroxytryptamine5 Serotonin Membrane Receptor and a Vitelline Envelope-Associated High Affinity Binding Site. J. Biol. Chem. 1993, 268, 7983–7989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manger, P.; Li, J.; Christensen, B.M.; Yoshino, T.P. Biogenic Monoamines in the Freshwater Snail, Biomphalaria Glabrata: Influence of Infection by the Human Blood Fluke, Schistosoma Mansoni. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Physiol. 1996, 114, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voronezhskaya, E.E. Maternal Serotonin: Shaping Developmental Patterns and Behavioral Strategy on Progeny in Molluscs. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2021, 9, 739787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maj, J.; Rogóz, Z. Pharmacological Effects of Venlafaxine, a New Antidepressant, given Repeatedly, on the Alpha 1-Adrenergic, Dopamine and Serotonin Systems. J. Neural Transm. 1999, 106, 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faquih, A.E.; Memon, R.I.; Hafeez, H.; Zeshan, M.; Naveed, S. A Review of Novel Antidepressants: A Guide for Clinicians. Cureus 2019, 11, e4185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jokela, J.; Lively, C.M.; Dybdahl, M.F.; Fox, J.A. Evidence for a Cost of Sex in the Freshwater Snail. Ecology 1997, 78, 452–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahl, S.M. Mechanism of Action of Trazodone: A Multifunctional Drug. CNS Spectrums 2009, 14, 536–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cann-Moisan, C.; Nicolas, L.; Robert, R. Ontogenic Changes in the Contents of Dopamine, Norepinephrine and Serotonin in Larvae and Postlarvae of the Bivalve Pecten Maximus. Aquat. Living Resour. 2002, 15, 313–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messenger, J.B.; Cornwell, C.J.; Reed, C.M. L-Glutamate and Serotonin Are Endogenous in Squid Chromatophore Nerves. J. Exp. Biol. 1997, 200, 3043–3054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messenger, J.B. Cephalopod Chromatophores: Neurobiology and Natural History. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 2001, 76, 473–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florey, E.; Kriebel, M.E. Electrical and Mechanical Responses of Chromatophore Muscle Fibers of the Squid, Loligo Opalescens, to Nerve Stimulation and Drugs. Z. Vgl. Physiol. 1969, 65, 98–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellner, M.; Porseryd, T.; Porsch-Hällström, I.; Borg, B.; Roufidou, C.; Olsén, K.H. Developmental Exposure to the SSRI Citalopram Causes Long-Lasting Behavioural Effects in the Three-Spined Stickleback (Gasterosteus aculeatus). Ecotoxicology 2018, 27, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shomrat, T.; Feinstein, N.; Klein, M.; Hochner, B. Serotonin Is a Facilitatory Neuromodulator of Synaptic Transmission and “Reinforces” Long-Term Potentiation Induction in the Vertical Lobe of Octopus vulgaris. Neuroscience 2010, 169, 52–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shigeno, S.; Andrews, P.L.R.; Ponte, G.; Fiorito, G. Cephalopod Brains: An Overview of Current Knowledge to Facilitate Comparison with Vertebrates. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, S.; de Vries, R.B.M.; Stephens, M.L.; Beck, N.B.; Dirven, H.A.A.M.; Fowle, J.R.; Goodman, J.E.; Hartung, T.; Kimber, I.; Lalu, M.M.; et al. A Primer on Systematic Reviews in Toxicology. Arch. Toxicol. 2017, 91, 2551–2575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

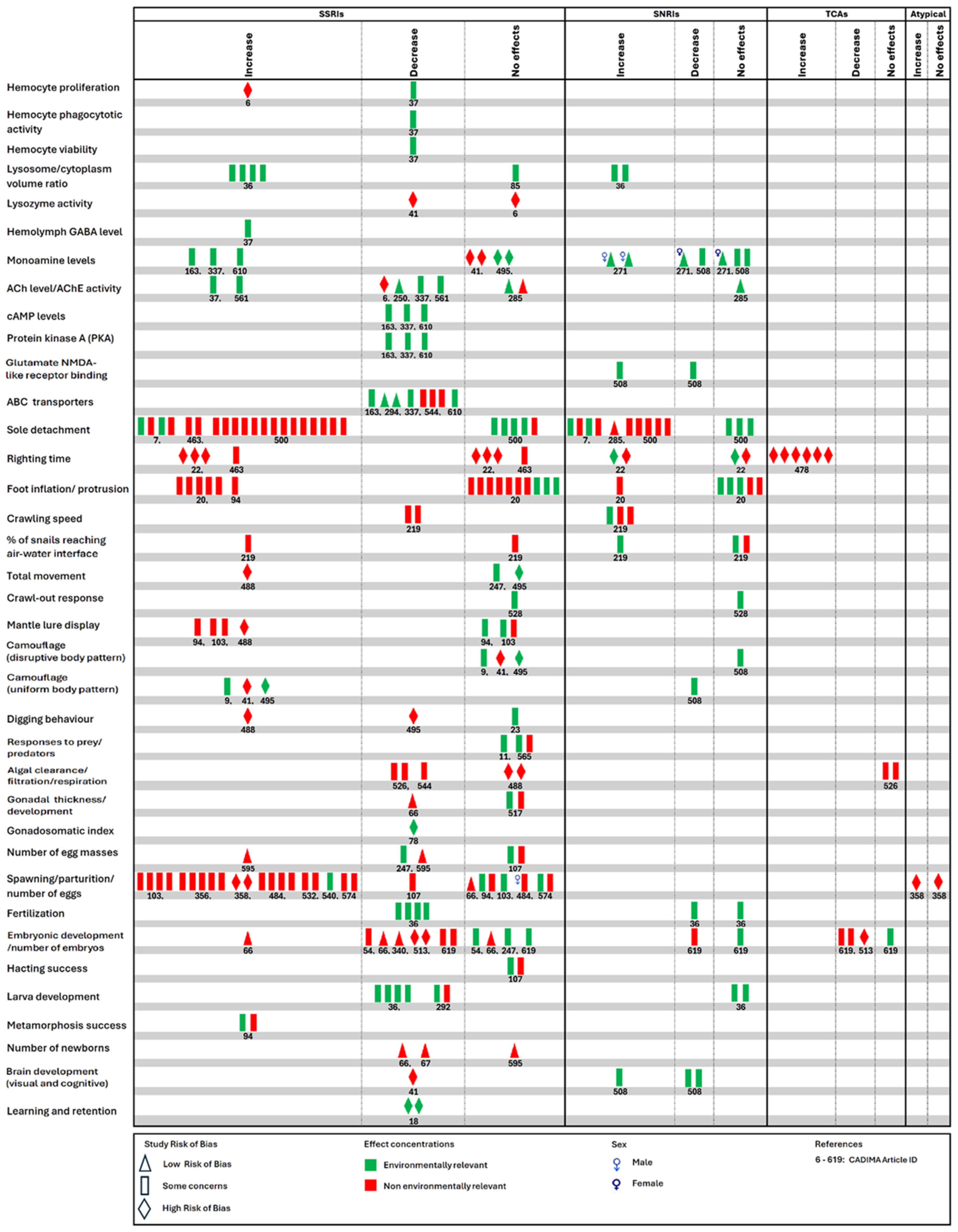

| Reported Outcomes | Range of Evidence Levels Across All Studies for Each Outcome |

|---|---|

| Increase in hemocyte count/proliferation, foot protrusion/inflation, total movement, mantle lure display, digging behavior, number of egg masses and embryonic development; decrease in lysozyme activity, digging behavior, algal clearance/filtration, gonadal development, embryonic development, and number of newborns. | ‘Generally or definitely inconclusive’ |

| Increase in righting time | ‘Generally or definitely inconclusive’ to ‘very little or no evidence’ |

| Decrease in gonadosomatic index and retention (memory) | ‘Very little or no evidence’ |

| Increase in sole detachment, crawling speed, number of snails reaching air–water interface, spawning/parturition/number of eggs, and metamorphosis success; decrease in number of egg masses, larval and brain development. | ‘Generally or definitely inconclusive’ to ‘weak to moderate evidence’ |

| Increase in uniform body pattern (camouflage) | ‘Generally or definitely inconclusive’, and ‘very little or no evidence’ to ‘weak to moderate evidence’ |

| Increase in lysosome/cytoplasm volume ratio, hemolymph GABA level, glutamate NMDA-like receptor binding and brain development; decrease in hemocyte proliferation, hemocyte phagocytotic activity, hemocyte viability, cAMP level, protein kinase A, NMDA-like receptor binding, camouflage (uniform body pattern) and fertilization | ‘Weak to moderate evidence’ |

| Decrease in acetylcholinesterase activity and ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter levels. | ‘Generally or definitely inconclusive’ and ‘weak to moderate evidence’ to ‘strong evidence’ |

| Increase in monoamine levels. | ‘Weak to moderate evidence’ to ‘strong evidence’ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Imiuwa, M.E.; Baynes, A.; Routledge, E.J. Understanding Target-Specific Effects of Antidepressant Drug Pollution on Molluscs: A Systematic Review Report. Toxics 2025, 13, 1043. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121043

Imiuwa ME, Baynes A, Routledge EJ. Understanding Target-Specific Effects of Antidepressant Drug Pollution on Molluscs: A Systematic Review Report. Toxics. 2025; 13(12):1043. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121043

Chicago/Turabian StyleImiuwa, Maurice E., Alice Baynes, and Edwin J. Routledge. 2025. "Understanding Target-Specific Effects of Antidepressant Drug Pollution on Molluscs: A Systematic Review Report" Toxics 13, no. 12: 1043. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121043

APA StyleImiuwa, M. E., Baynes, A., & Routledge, E. J. (2025). Understanding Target-Specific Effects of Antidepressant Drug Pollution on Molluscs: A Systematic Review Report. Toxics, 13(12), 1043. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121043