Biomonitoring of Silver in Children and Adolescents from Alcalá de Henares (Spain): Assessing Potential Health Risks from Topsoil Contamination

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

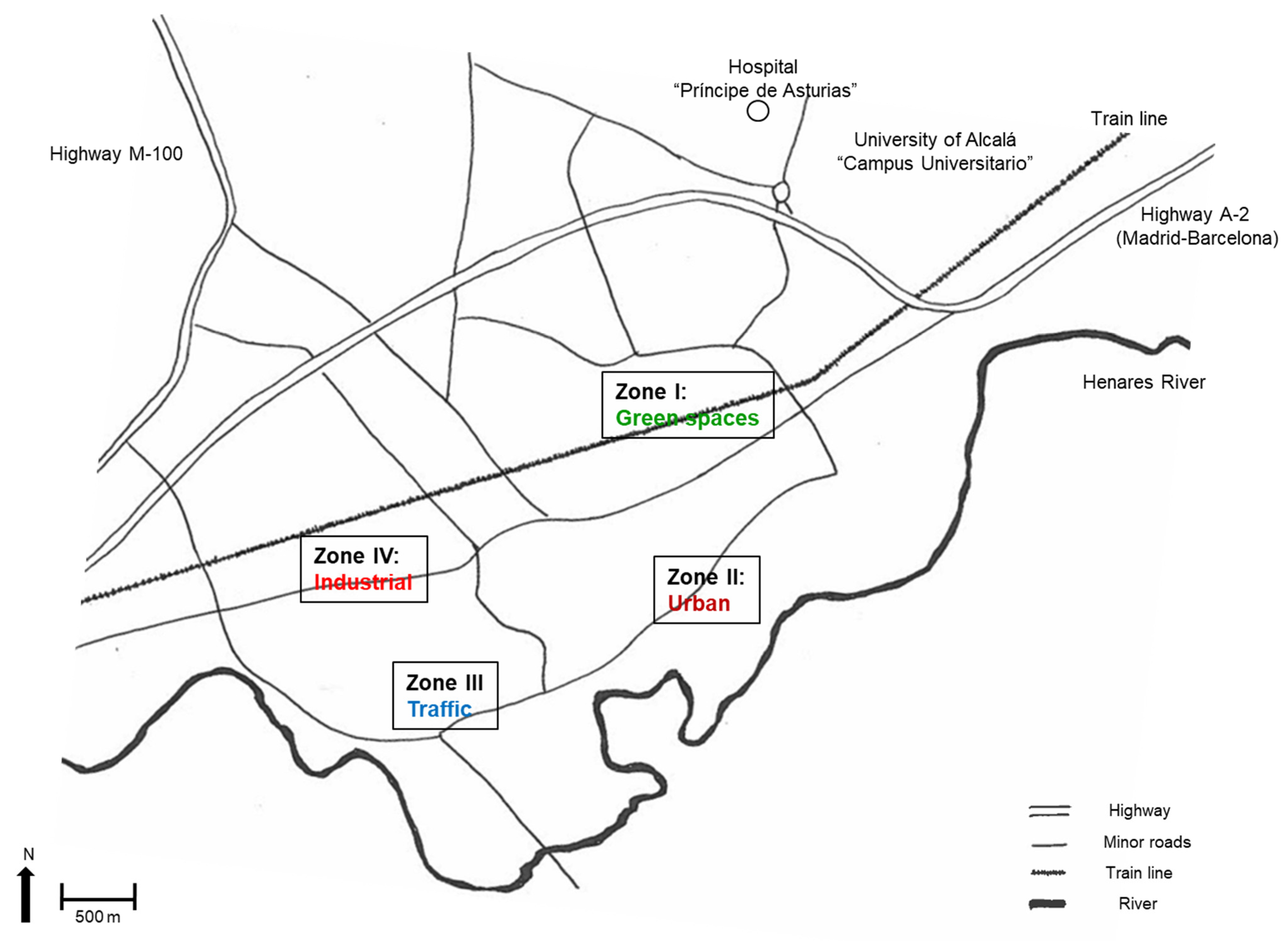

2.1. Site Characteristics

2.2. Scalp-Hair Sampling

2.3. Reference Values

2.4. Topsoil Samples

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Ag in Hair of Children and Adolescents

3.2. Sex Differences

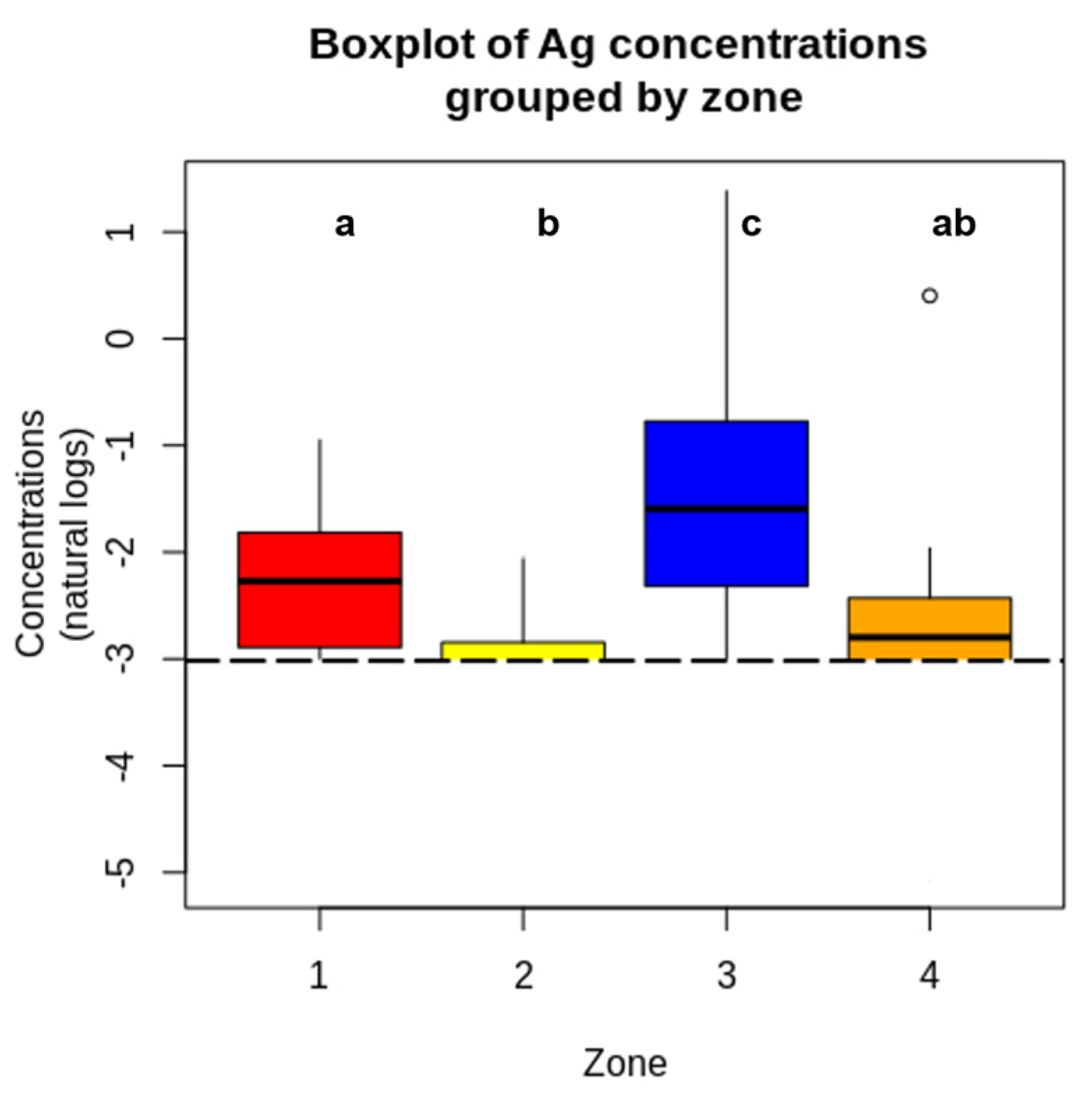

3.3. Residential Areas

3.4. Correlations Between Hair and Topsoils

3.5. Risk Characterisation

3.6. “Reference Values” of Ag in Hair

4. Discussion

4.1. Hair Ag Levels in Children and Adolescents

4.2. Sex, Residential Area and Environmental Contributions

4.3. Reference Values

4.4. Study Limitations and Strengths

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aylward, L.L.; Bachler, G.; von Goetz, N.; Poddalgoda, D.; Hays, S.M.; Nong, A. Biomonitoring Equivalents for interpretation of silver biomonitoring data in a risk assessment context. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2016, 219, 521–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocca, B.; Battistini, B.; Petrucci, F. Silver and gold nanoparticles characterization by SP-ICP-MS and AF4-FFF-MALS-UV-ICP-MS in human samples used for biomonitoring. Talanta 2020, 220, 121404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGillicuddy, E.; Murray, I.; Kavanagh, S.; Morrison, L.; Fogarty, A.; Cormican, M.; Dockery, P.; Prendergast, M.; Rowan, N.; Morris, D. Silver nanoparticles in the environment: Sources, detection and ecotoxicology. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 575, 231–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US Department of Health and Human Services. CERCLA Priority List of Hazardous Substances That Will Be the Subject of Toxicological Profiles and Support Document. Department of Toxicology, Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. Available online: https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/programs/substance-priority-list.html?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/spl/ (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Galizia, A.; Falchi, L.; Iaquinta, F.; Machado, I. Biomonitoring of Potentially Toxic Elements in Dyed Hairs and Its Correlation with Variables of Interest. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2024, 202, 3529–3537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Momčilović, B.; Prejac, J.; Višnjević, V.; Mimica, N.; Morović, S.; Čelebić, A.; Drmić, S.; Skalny, A.V. Environmental human silver exposure. Toxicol. Environ. Chem. 2012, 94, 1238–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña-Fernández, A.; Lobo-Bedmar, M.C.; González-Muñoz, M.J. Monitoring lead in hair of children and adolescents of Alcalá de Henares, Spain. A study by gender and residential areas. Environ. Int. 2014, 72, 170–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballesteros, M.T.L.; Serrano, I.N.; Álvarez, S.I. Reference levels of trace elements in hair samples from children and adolescents in Madrid, Spain. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2017, 43, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ougier, E.; Ganzleben, C.; Lecoq, P.; Bessems, J.; David, M.; Schoeters, G.; Lange, R.; Meslin, M.; Uhl, M.; Kolossa-Gehring, M.; et al. Chemical prioritisation strategy in the European human biomonitoring initiative (HBM4EU)–development and results. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2021, 236, 113778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faure, S.; Noisel, N.; Werry, K.; Karthikeyan, S.; Aylward, L.L.; St-Amand, A. Evaluation of human biomonitoring data in a health risk based context: An updated analysis of population level data from the Canadian Health Measures Survey. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2020, 223, 267–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, F., Jr.; Devoz, P.P.; Cavalcante, M.R.; Gallimberti, M.; Cruz, J.C.; Domingo, J.L.; Simões, E.J.; Lotufo, P.; Liu, S.; Bensenor, I. Urinary levels of 30 metal/metalloids in the Brazilian southeast population: Findings from the Brazilian Longitudinal Study of Adult Health (ELSA-Brasil). Environ. Res. 2023, 225, 115624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC); National Center for Environmental Health. National Report on Human Exposure to Environmental Chemicals; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Schmied, A.; Murawski, A.; Kolossa-Gehring, M.; Kujath, P. Determination of trace elements in urine by inductively coupled plasma-tandem mass spectrometry–biomonitoring of adults in the German capital region. Chemosphere 2021, 285, 131425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Lin, S.; Zhao, F.; Lv, Y.; Qu, Y.; Hu, X.; Yu, S.; Song, S.; Lu, Y.; Yan, H.; et al. Cohort profile: China National Human Biomonitoring (CNHBM)—A nationally representative, prospective cohort in Chinese population. Environ. Int. 2021, 146, 106252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govarts, E.; Gilles, L.; Martin, L.R.; Santonen, T.; Apel, P.; Alvito, P.; Anastasi, E.; Andersen, H.R.; Andersson, A.M.; Andryskova, L.; et al. Harmonized human biomonitoring in European children, teenagers and adults: EU-wide exposure data of 11 chemical substance groups from the HBM4EU Aligned Studies (2014–2021). Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2023, 249, 114119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- INE (Instituto Nacional de Estadística). Cifras Oficiales de Población Resultantes de la Revisión del Padrón Municipal a 1 de Enero. Detalle Municipal. Madrid: Población por Municipios y Sexo. Available online: https://www.ine.es/jaxiT3/Datos.htm?t=2881#!tabs-tabla (accessed on 24 February 2025).

- Esplugas, R.; Mari, M.; Marquès, M.; Schuhmacher, M.; Domingo, J.L.; Nadal, M. Biomonitoring of Trace Elements in Hair of Schoolchildren Living Near a Hazardous Waste Incinerator-A 20 Years Follow-Up. Toxics 2019, 7, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, M.; Yan, L.; Pang, Y.; Jia, X.; Huang, J.; Shen, G.; Cheng, H.; Wang, X.; Pan, B.; Li, Z.; et al. External interference from ambient air pollution on using hair metal (loid) s for biomarker-based exposure assessment. Environ. Int. 2020, 137, 105584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Granero, S.; Llobet, J.M.; Schuhmacher, M.; Corbella, J.; Domingo, J.L. Biological monitoring of environmental pollution and human exposure to metals in Tarragona, Spain. I. Levels in hair of school children. Trace Elem. Electrolytes 1998, 15, 39–43. [Google Scholar]

- Nadal, M.; Bocio, A.; Schuhmacher, M.; Domingo, J.L. Monitoring metals in the population living in the vicinity of a hazardous waste incinerator: Levels in hair of school children. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2005, 104, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caron-Beaudoin, É.; Bouchard, M.; Wendling, G.; Barroso, A.; Bouchard, M.F.; Ayotte, P.; Frohlich, K.L.; Verner, M.A. Urinary and hair concentrations of trace metals in pregnant women from Northeastern British Columbia, Canada: A pilot study. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 2019, 29, 613–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulsen, O.M.; Holst, E.; Christensen, J.M. Calculation and application of coverage intervals for biological reference values. Pure Appl. Chem. 1997, 69, 1601–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santonen, T.; Mahiout, S.; Alvito, P.; Apel, P.; Bessems, J.; Bil, W.; Borges, T.; Bose-O’Reilly, S.; Buekers, J.; Portilla, A.I.; et al. How to use human biomonitoring in chemical risk assessment: Methodological aspects, recommendations, and lessons learned from HBM4EU. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2023, 249, 114139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña-Fernández, A.; Higueras, M.; Tepanosyan, G.; Peña, M.A.; Lobo-Bedmar, M.C. Human health risks of less-regulated and monitored metal(loid)s in urban and industrial topsoils from Alcalá de Henares, Spain. Sci. Rep. 2025; submitted. [Google Scholar]

- Peña-Fernández, A.; González-Muñoz, M.J.; Lobo-Bedmar, M.C. Establishing the importance of human health risk assessment for metals and metalloids in urban environments. Environ. Int. 2014, 72, 176–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EPA/540/1-89/002; Risk Assessment Guidance for Superfund. Volume 1: Human Health Evaluation Manual (Parte A); US EPA: Washington, DC, USA, 1989.

- Rovira, J.; Nadal, M.; Schuhmacher, M.; Domingo, J.L. Environmental levels of PCDD/Fs and metals around a cement plant in Catalonia, Spain, before and after alternative fuel implementation. Assessment of human health risks. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 485, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA). Regional Screening Levels (RSLs)-Generic Tables. Tables as of: November 2023. San Francisco, CA 94105. 2023. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/risk/regional-screening-levels-rsls-generic-tables (accessed on 8 May 2024).

- Helsel, D.R. Statistics for Censored Environmental Data Using Minitab and R; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011; Volume 77. [Google Scholar]

- Shoari, N.; Dubé, J.S. Toward improved analysis of concentration data: Embracing nondetects. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2018, 37, 643–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2025; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Izydorczyk, G.; Mironiuk, M.; Baśladyńska, S.; Mikulewicz, M.; Chojnacka, K. Hair mineral analysis in the population of students living in the Lower Silesia region (Poland) in 2019: Comparison with biomonitoring study in 2009 and literature data. Environ. Res. 2021, 196, 110441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berglund, M.; Lindberg, A.L.; Rahman, M.; Yunus, M.; Grandér, M.; Lönnerdal, B.; Vahter, M. Gender and age differences in mixed metal exposure and urinary excretion. Environ. Res. 2011, 111, 1271–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varrica, D.; Tamburo, E.; Milia, N.; Vallascas, E.; Cortimiglia, V.; De Giudici, G.; Dongarrà, G.; Sanna, E.; Monna, F.; Losno, R. Metals and metalloids in hair samples of children living near the abandoned mine sites of Sulcis-Inglesiente (Sardinia, Italy). Environ. Res. 2014, 134, 366–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, F.L.; Cournil, A.; Souza Sarkis, J.E.; Bénéfice, E.; Gardon, J. Hair trace elements concentration to describe polymetallic mining waste exposure in Bolivian Altiplano. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2011, 139, 10–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goullé, J.P.; Mahieu, L.; Castermant, J.; Neveu, N.; Bonneau, L.; Lainé, G.; Bouige, D.; Lacroix, C. Metal and metalloid multi-elementary ICP-MS validation in whole blood, plasma, urine and hair: Reference values. Forensic Sci. Int. 2005, 153, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chojnacka, K.; Zielińska, A.; Górecka, H.; Dobrzański, Z.; Górecki, H. Reference values for hair minerals of Polish students. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2010, 29, 314–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chojnacka, K.; Michalak, I.; Zielińska, A.; Górecki, H. Assessment of the exposure to elements from silver jewelry by hair mineral analysis. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2011, 61, 512–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdous, Z.; Nemmar, A. Health Impact of Silver Nanoparticles: A Review of the Biodistribution and Toxicity Following Various Routes of Exposure. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA Panel on Food Contact Materials; Enzymes and Processing Aids (CEP); Lambré, C.; Barat Baviera, J.M.; Bolognesi, C.; Chesson, A.; Cocconcelli, P.S.; Crebelli, R.; Gott, D.M.; Grob, K.; et al. Safety assessment of the substance silver nanoparticles for use in food contact materials. EFSA J. Eur. Food Saf. Auth. 2021, 19, e06790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.J.; Wei, S.Q.; Sun, Y.X.; Yang, T.; Li, Q.; Wang, D.X. Levels of five metals in male hair from urban and rural areas of Chongqing, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2016, 23, 22163–22171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Population | LoD | % < LoD | Arithmetic Mean | Geometric Mean | Median | Range | Interquartile Range | P95 | CI-PP95 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Children | Female | 0.0036 | 0 | 0.1912 ± 0.3387 * | 0.1201 | 0.1205 | 0.0168–2.6906 | 0.0747, 0.1867 | 0.4577 | 0.2635–1.0817 |

| Male | 0 | 0.1082 ± 0.0804 | 0.0848 | 0.0892 | 0.0139–0.3841 | 0.0436, 0.1402 | 0.3058 | 0.1758–0.3582 | ||

| Total | 0 | 0.1566 ± 0.2668 | 0.1016 | 0.1120 | 0.0139–2.6906 | 0.0623, 0.1679 | 0.3504 | 0.2866–0.5383 | ||

| Adolescents | Female | 0.0224 | 16.2 | 0.5401 ± 1.4498 ** | 0.1200 | 0.1057 | 0.0225–9.9268 | 0.0346, 0.4215 | 2.3554 | 0.6547–6.0749 |

| Male | 27.6 | 0.0762 ± 0.1021 | 0.0401 | 0.0387 | 0.0273–0.5023 | 0.0224, 0.0606 | 0.3071 | 0.0606–0.3071 | ||

| Total | 19.6 | 0.4010 ± 1.2310 | 0.0839 | 0.0695 | 0.0225–9.9268 | 0.0308, 0.2487 | 1.3401 | 0.5248–3.0795 | ||

| Population | Zone | n | % < LoD | Mean | SD | LCL Mean | UCL Mean | Median | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Children | I | 24 | 0 | 0.1076 | 0.1042 | 0.0636 | 0.1516 | 0.0778 | 0.172 |

| II | 60 | 0 | 0.1963 | 0.3648 | 0.1020 | 0.2905 | 0.1201 | ||

| IV | 36 | 0 | 0.1232 | 0.0714 | 0.0991 | 0.1474 | 0.1077 | ||

| Adolescents | I | 36 | 36.11 | 0.1333 a | 0.1927 | 0.0665 | 0.1948 | 0.0320 | 0.0004 |

| II | 20 | 5.0 | 1.2930 b | 2.4490 | 0.1157 | 2.4682 | 0.2145 | ||

| III | 24 | 4.17 | 0.2095 b | 0.2865 | 0.0859 | 0.3324 | 0.0887 | ||

| IV | 17 | 23.53 | 0.1916 ab | 0.3136 | 0.0237 | 0.3545 | 0.0695 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Peña-Fernández, A.; Higueras, M.; Valiente, R.; Lobo-Bedmar, M.C. Biomonitoring of Silver in Children and Adolescents from Alcalá de Henares (Spain): Assessing Potential Health Risks from Topsoil Contamination. Toxics 2025, 13, 1026. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121026

Peña-Fernández A, Higueras M, Valiente R, Lobo-Bedmar MC. Biomonitoring of Silver in Children and Adolescents from Alcalá de Henares (Spain): Assessing Potential Health Risks from Topsoil Contamination. Toxics. 2025; 13(12):1026. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121026

Chicago/Turabian StylePeña-Fernández, Antonio, Manuel Higueras, Roberto Valiente, and M. Carmen Lobo-Bedmar. 2025. "Biomonitoring of Silver in Children and Adolescents from Alcalá de Henares (Spain): Assessing Potential Health Risks from Topsoil Contamination" Toxics 13, no. 12: 1026. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121026

APA StylePeña-Fernández, A., Higueras, M., Valiente, R., & Lobo-Bedmar, M. C. (2025). Biomonitoring of Silver in Children and Adolescents from Alcalá de Henares (Spain): Assessing Potential Health Risks from Topsoil Contamination. Toxics, 13(12), 1026. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121026