Increased PM2.5 Caused by Enhanced Fireworks Burning and Secondary Aerosols in a Forested City of North China During the 2023–2025 Spring Festivals

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

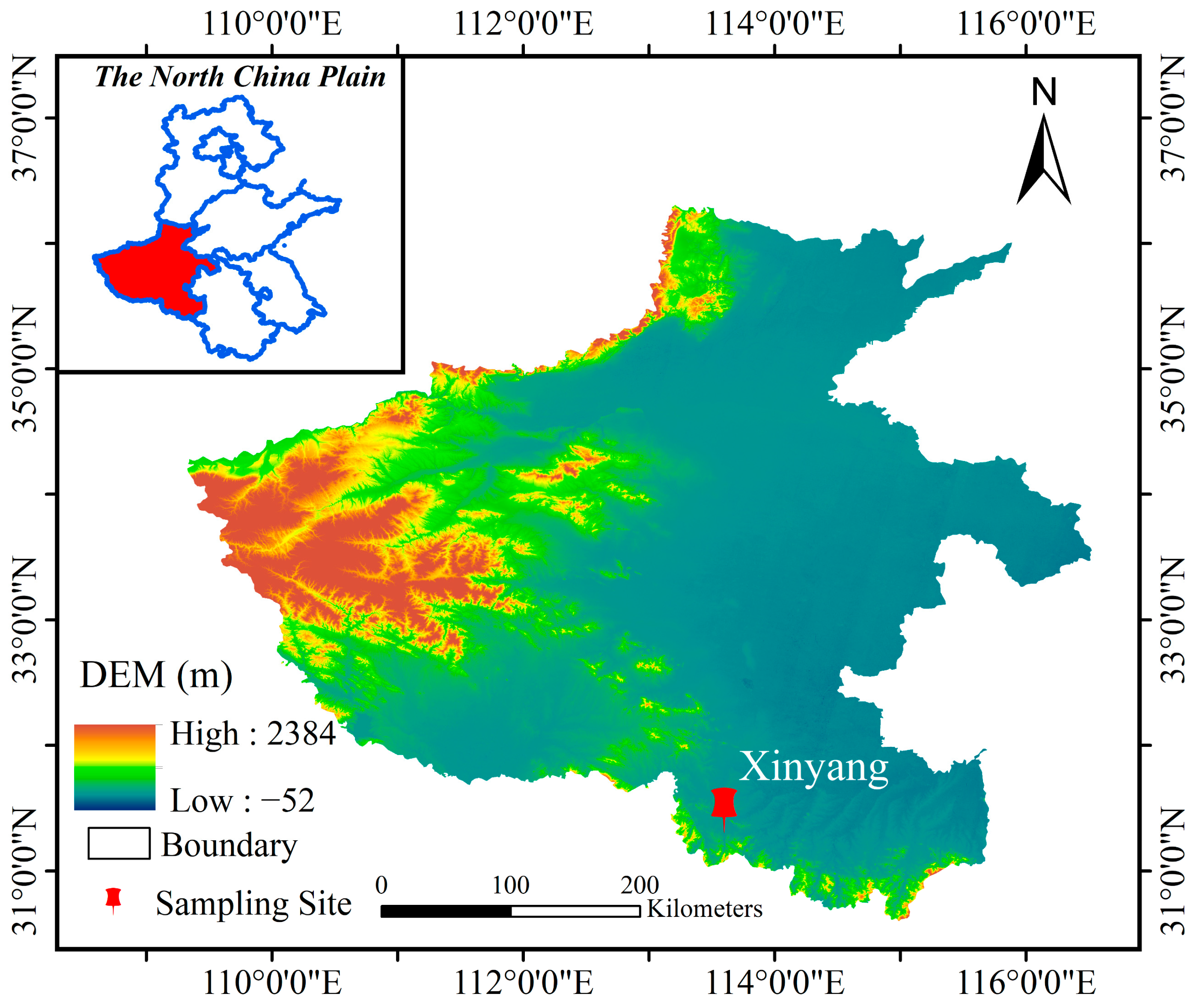

2.1. Observational Site

2.2. Sample Collection and Laboratory Analysis

2.3. Analysis Methods

2.3.1. Acidity of PM2.5 Acidity

2.3.2. Nitrogen and Sulfur Oxidation Ratios

2.3.3. Source Apportionment of PM2.5 Positive Matrix Factorization (PMF) Model

3. Results and Discussion

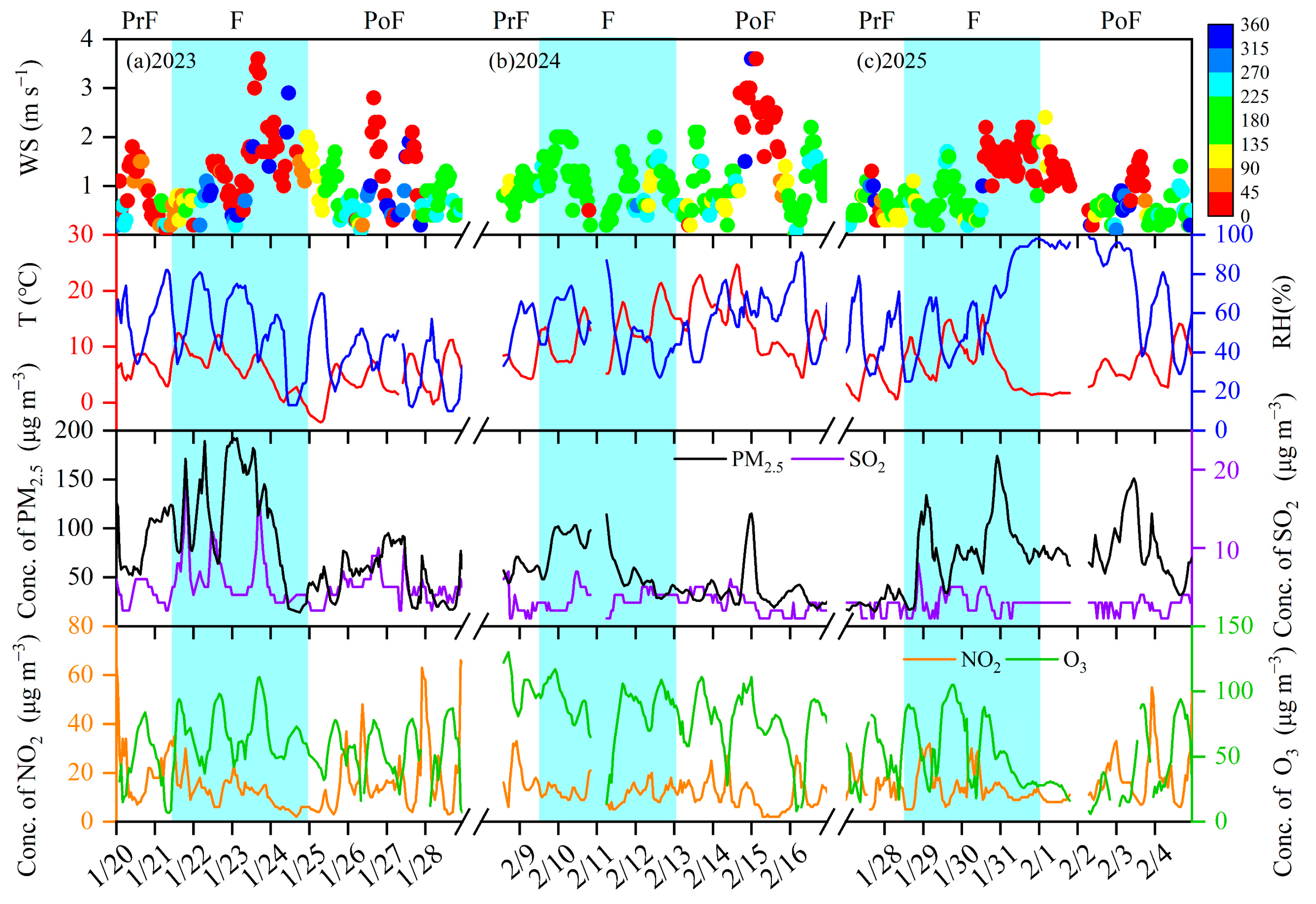

3.1. The Variations in Meteorological Conditions and Air Pollutants During the Spring Festival

3.2. Impacts of Fireworks on Chemical Components and Aerosol Acid During the Spring Festival

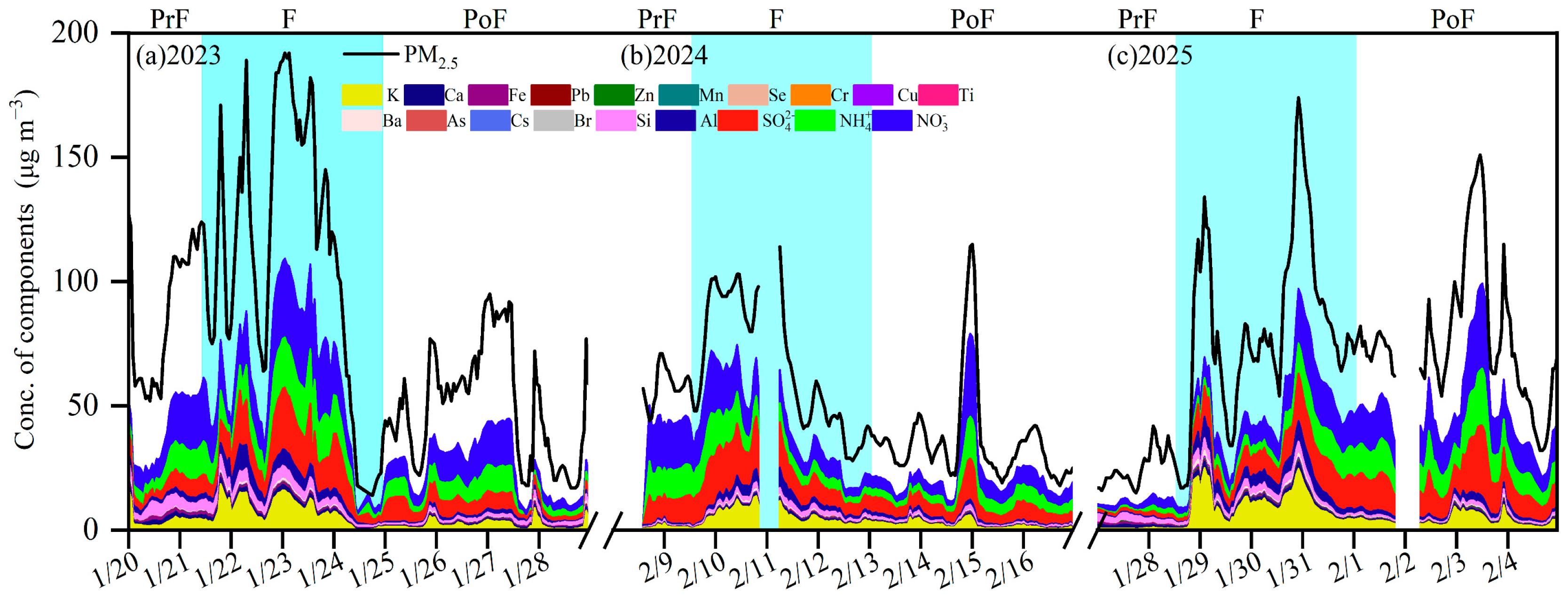

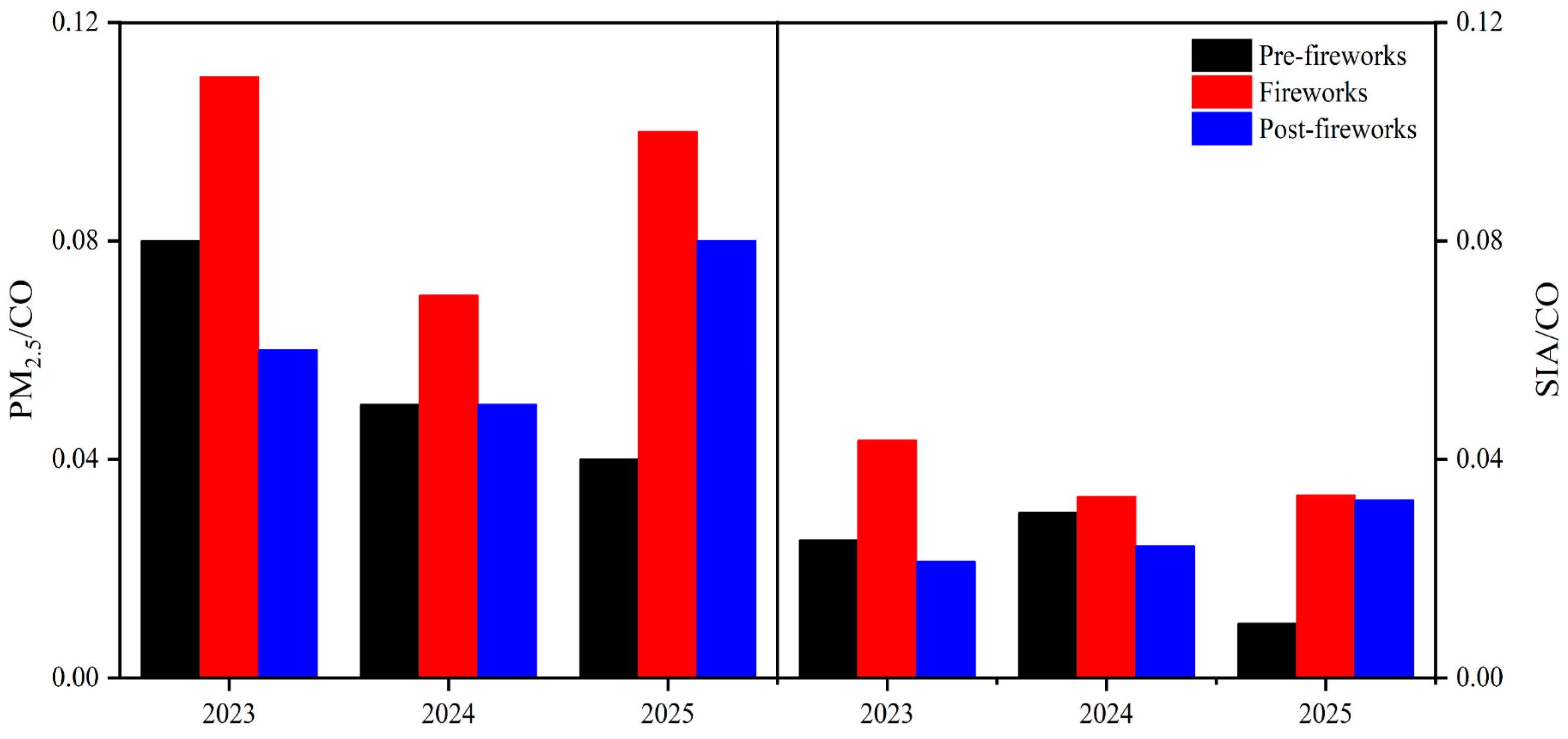

3.2.1. Changes in Elemental Compositions and SIA

3.2.2. Acidity of PM2.5

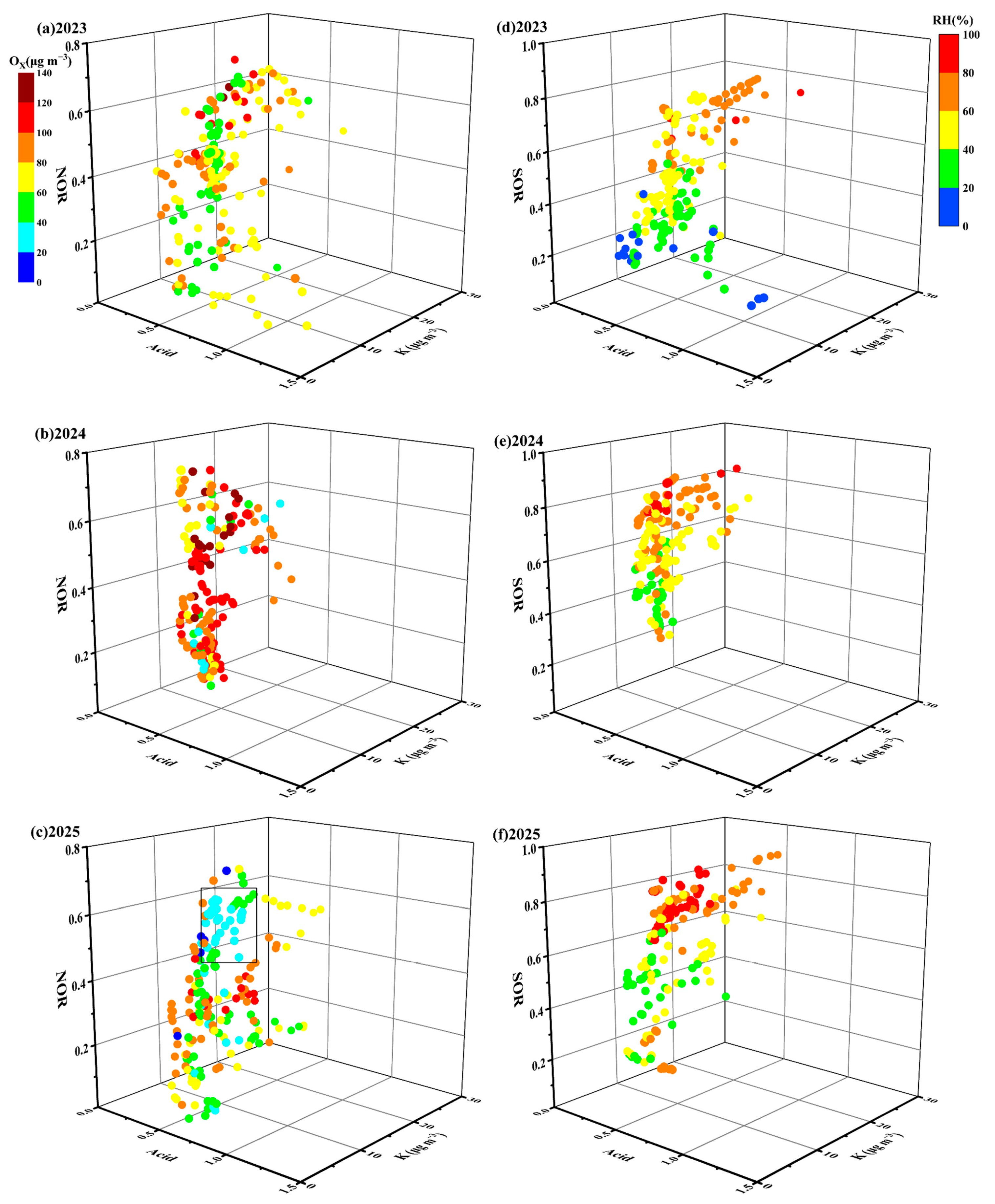

3.3. Nitrate and Sulfate Formation Mechanism

| Parameters | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | During | Post | Pre | During | Post | Pre | During | Post | |

| SOR | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 0.7 | 0.8 |

| NOR | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.5 |

| RH | 59.3 | 53.2 | 35.8 | 55.2 | 51.6 | 58.3 | 50.2 | 60.9 | 77.3 |

| T | 6.1 | 6.5 | 3.9 | 5.9 | 12.4 | 14.1 | 3.8 | 7.5 | 5.6 |

| Ws | 0.7 | 1.3 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 1.4 | 0.6 | 1.0 | 0.8 |

| SO2 | 4.0 | 6.2 | 4.8 | 2.7 | 3.5 | 2.8 | 2.3 | 3.0 | 2.7 |

| NO2 | 21.7 | 12.4 | 17.6 | 19.1 | 12.1 | 10.9 | 14.1 | 14.3 | 16.5 |

| Ox | 62.4 | 86.4 | 67.1 | 121.4 | 100.5 | 74.8 | 60.3 | 72.2 | 52.2 |

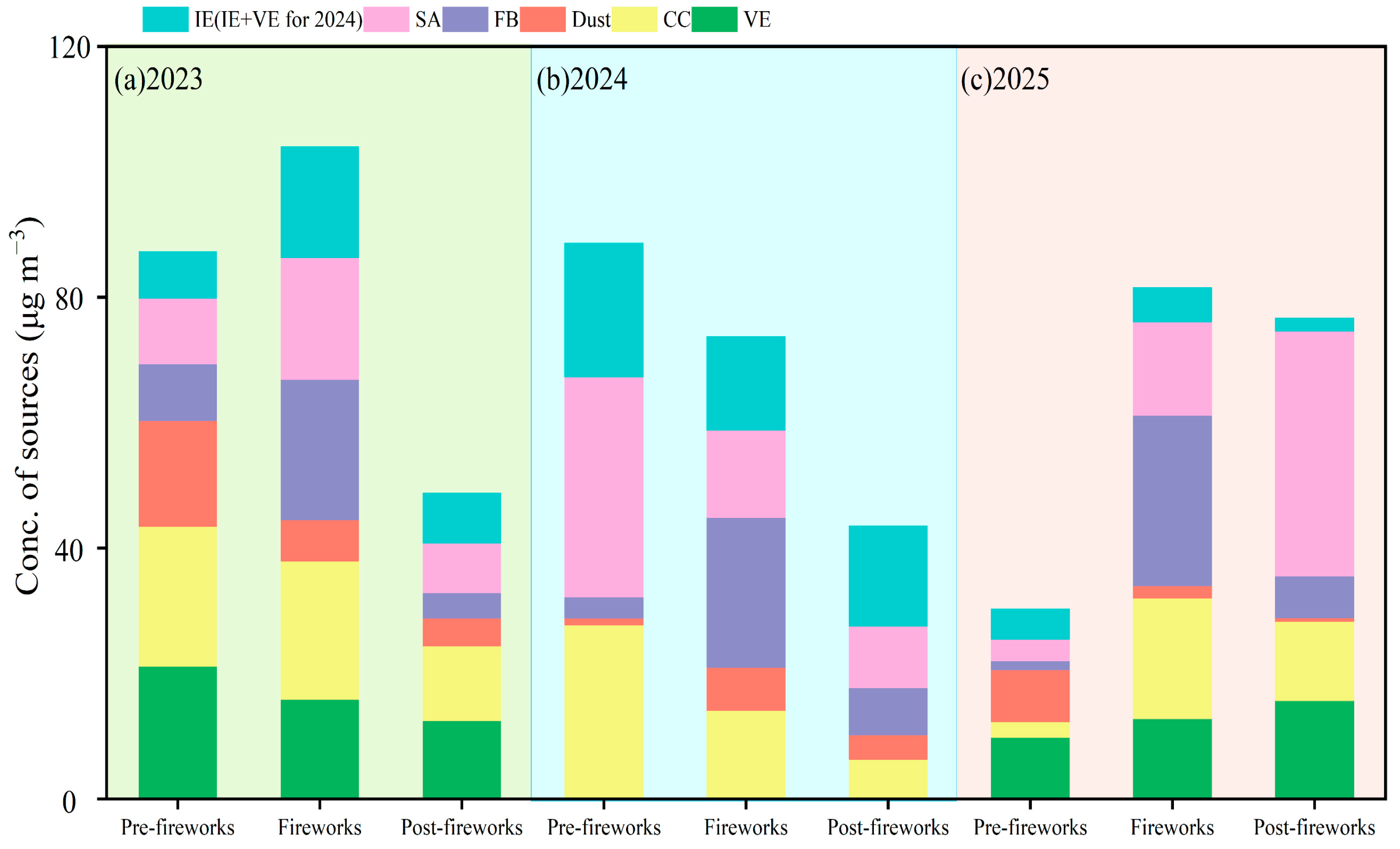

3.4. Source Apportionment of PM2.5

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| XY | Xinyang |

| FB | Fireworks burning |

| VE | Vehicle emissions |

| IE | Industrial emissions |

| IE + VE | Industrial emissions + Vehicle emissions |

| SA | Secondary aerosols |

| CC | Coal combustion |

References

- Fan, S.D.; Li, Y.; Liu, C.F. Are Environmentally Friendly Fireworks Really “Green” for Air Quality? A Study from the 2019 National Day Fireworks Display in Shenzhen. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 3520–3529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, G.H.; Cai, M.; Meng, R.L.; Hu, J.X.; Peng, K.; Hou, Z.L.; Zhou, C.L.; Xu, X.J.; Xiao, Y.Z.; Yu, M.; et al. The Spring Festival Is Associated with Increased Mortality Risk in China: A Study Based on 285 Chinese Locations. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 761060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.Y.; Wei, J.M.; Tang, A.H.; Zheng, A.H.; Shao, Z.X.; Liu, X.J. Chemical characteristics of PM2.5 during 2015 Spring Festival in Beijing, China. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2017, 17, 1169–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidel, D.J.; Birnbaum, A.N. Effects of Independence Day fireworks on atmospheric concentrations of fine particulate matter in the United States. Atmos. Environ. 2015, 115, 192–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.C. A review of the impact of fireworks on particulate matter in ambient air. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 2016, 66, 1171–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, P.; Furger, M.; Slowik, J.G.; Canonaco, F.; Fröhlich, R.; Hüglin, C.; Minguillón, M.C.; Patterson, K.; Baltensperger, U.; Prévôt, A.S.H. Source apportionment of highly time-resolved elements during a firework episode from a rural freeway site in Switzerland. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2020, 20, 1657–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andradottir, H.O.; Thorsteinsson, T. Repeated extreme particulate matter episodes due to fireworks in Iceland and stakeholders’ response. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 236, 117511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drewnick, F.; Hings, S.S.; Curtius, J.; Eerdekens, G.; Williams, J. Measurement of fine particulate and gas-phase species during the New Year’s fireworks 2005 in Mainz, Germany. Atmos. Environ. 2006, 40, 4316–4327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.Y.; Zhang, X.L.; Tong, D.Q.; Chen, W.W.; Zhang, S.C.; Zhao, H.M.; Xiu, A.J. Review on physicochemical properties of pollutants released from fireworks: Environmental and health effects and prevention. Environ. Rev. 2018, 26, 133–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.X.; Duan, J.C.; Liu, S.J.; Hu, J.N.; Zhang, M.; Kang, P.; Wang, C. Evaluation of the effect of fireworks prohibition in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei and surrounding areas during the Spring Festival of 2018. Res. Environ. Sci. 2019, 32, 203–211. [Google Scholar]

- Song, S.J.; Gao, M.; Xu, W.Q.; Shao, J.Y.; Shi, G.L.; Wang, S.X.; Wang, Y.X.; Sun, Y.; McElroy, M.B. Fine-particle pH for Beijing winter haze as inferred from different thermodynamic equilibrium models. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2018, 18, 7423–7438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Zhao, P.S.; Su, J.; Dong, Q.; Du, X.; Zhang, Y.F. Aerosol pH and its driving factors in Beijing. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2019, 19, 7939–7954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Wang, G.H.; Wang, J.Y.; Li, J.J.; Ren, Y.Q.; Zhang, L.; Cao, C.; Li, J.; Ge, S.S.; Xie, Y.N.; et al. Chemical characteristics of haze particles in Xi’an during Chinese Spring Festival: Impact of fireworks displays. J. Environ. Sci. 2018, 71, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.Z.; Wang, J.; Peng, X.; Shi, G.L.; Feng, Y.C. Estimation of the direct and indirect impacts of fireworks on the physicochemical characteristics of atmospheric PM10 and PM2.5. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2014, 14, 9469–9479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foreback, B.; Dada, L.; Daellenbach, K.R.; Yan, C.; Wang, L.L.; Chu, B.W.; Zhou, Y.; Kokkonen, T.V.; Kurppa, M.; Pileci, R.E.; et al. Measurement Report: A Multi-Year Study on the Impacts of Chinese New Year Celebrations on Air Quality in Beijing, China. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2022, 22, 11089–11104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.Y.; Jiang, L.D.; Liu, W.L.; Song, H. Fireworks Regulation, Air Pollution, and Public Health: Evidence from China. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 2022, 92, 103722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.X.; Gu, X.C.; Cheng, C.X.; Yang, D.Y. Spatiotemporal heterogeneity of PM2.5 and its relationship with urbanization in North China from 2000 to 2017. Sci. Total. Environ. 2020, 20, 744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.Y.; Zhao, C.M.; Shen, X.Z.; Jin, T. Spatiotemporal variations and sources of PM2.5 in the Central Plains Urban Agglomeration, China. Air Qual. Atmos. Health 2022, 15, 1507–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HJ 817-2018.; Technical Specifications for Operation and Quality Control of Ambient Air Quality Automated Monitoring System for Particulate Matter (PM10 and PM2.5). Ministry of Ecology and Environment: Beijing, China, 2018.

- GB/T 36090-2018; Gas Analysis—Guide for Quality Assurance of On-Line Automatic Measuring System. General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine, Standardization Administration: Beijing, China, 2018.

- Liu, B.S.; Yang, J.M.; Yuan, J.; Dai, Q.L.; Li, T.K.; Bi, X.H.; Feng, Y.C.; Xiao, Z.M.; Zhang, Y.F.; Xu, H. Source apportionment of atmospheric pollutants based on the online data by using PMF and ME2 models at a megacity, China. Atmos. Res. 2017, 185, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- QX/T 291-2015; Field-Calibration Method for Data Logger of Automatic Weather Station. China Meteorological Administration: Beijing, China, 2015.

- Qiao, B.Q.; Chen, Y.; Tian, M.; Wang, H.B.; Yang, F.M.; Shi, G.M.; Zhang, L.M.; Peng, C.; Luo, Q.; Ding, S.M. Characterization of water soluble inorganic ions and their evolution processes during PM2.5 pollution episodes in a small city in southwest China. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 650, 2605–2613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhao, Q.; Ma, Y.; Duan, F.; Yang, F.; Shi, Z.; Chen, G. Spatial and seasonal variability of PM2.5 acidity at two Chinese megacities: Insights into the formation of secondary inorganic aerosols. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2012, 12, 1377–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.J.; Lü, C.W.; He, J.; Gao, M.S.; Zhao, B.Y.; Ren, L.M.; Zhang, L.J.; Fan, Q.Y.; Liu, T.; He, Z.X.; et al. Stoichiometry of water-soluble ions in PM2.5: Application in source apportionment for a typical industrial city in semi-arid region, Northwest China. Atmos. Res. 2018, 204, 149–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paatero, P.; Tapper, U. Positive matrix factorization: A non-negative factor model with optimal utilization of error estimates of data values. Environmetrics 1994, 5, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucarelli, F.; Calzolai, G.; Chiari, M.; Giardi, F.; Czelusniak, C.; Nava, S. Hourly Elemental Composition and Source Identification by Positive Matrix Factorization (PMF) of Fine and Coarse Particulate Matter in the High Polluted Industrial Area of Taranto (Italy). Atmosphere 2020, 11, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.W.; Ren, L.H.; Wu, Y.F.; Zhang, R.J.; Yang, X.Y.; Li, G.; Gao, E.H.; An, J.T.; Xu, Y.S. Different variations in PM2.5 sources and their specific health risks in different periods in a heavily polluted area of the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region of China. Atmos. Res. 2024, 308, 107519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, G.L.; Liu, G.R.; Tian, Y.Z.; Zhou, X.Y.; Peng, X.; Feng, Y.C. Chemical characteristic and toxicity assessment of particle associated PAHs for the short-term anthropogenic activity event: During the Chinese New Year’s Festival in 2013. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 482, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, C.; Chen, R.S.; Chen, M.X. The impacts of Chinese Nian culture on air pollution. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 112, 1740–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Man, Y.; Liu, Y. Temporal variability of PM10 and PM2.5 inside and outside a residential home during 2014 Chinese Spring Festival in Zhengzhou, China. Nat. Hazards 2014, 73, 2149–2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Zhuang, G.; Lin, Y.; Wang, Q.; Fu, J.S.; Zhang, R.; Li, J.; Deng, C.; Fu, Q. Impact of anthropogenic emission on air quality over a megacity-revealed from an intensive atmospheric campaign during the Chinese Spring Festival. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2012, 12, 11631–11645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Li, Q.; Huang, L.; Wang, Q.; Zhu, A.S.; Xu, J.; Liu, Z.Y.; Li, H.L.; Shi, L.S.; Li, R.; et al. Air quality changes during the COVID-19 lockdown over the Yangtze River Delta Region: An insight into the impact of human activity pattern changes on air pollution variation. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 732, 139282. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.T.; Strezov, V.; Jiang, Y.J.; Kan, T.; Evans, T. Temporal and spatial variations of air pollution across China from 2015 to 2018. J. Environ. Sci. 2022, 112, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, M.D.; Liu, X.G.; Tan, Q.W.; Feng, M.; Qu, Y.; An, J.L.; Zhang, Y.H. Characteristics and formation mechanism of persistent extreme haze pollution events in Chengdu, southwestern China. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 251, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Q.L.; Ding, J.; Hou, L.L.; Li, L.X.; Cai, Z.Y.; Liu, B.S.; Song, C.B.; Bi, X.H.; Wu, J.H.; Zhang, Y.F.; et al. Haze episodes before and during the COVID-19 shutdown in Tianjin, China: Contribution of fireworks and residential burning. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 286, 117252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambade, B. The air pollution during Diwali festival by the burning of fireworks in Jamshedpur city. India. Urban Clim. 2018, 26, 149–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanda, S.; Ličbinský, R.; Hegrová, J.; Goessler, W. Impact of NewYear’s Eve Fireworks on the Size Resolved Element Distributions in Airborne Particles. Environ. Int. 2019, 128, 371–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, T.; Querol, X.; Alastuey, A.; Amato, F.; Pey, J.; Pandolfi, M.; Kuenzli, N.; Bouso, L.; Rivera, M.; Gibbons, W. Effect of fireworks events on urban background trace metal aerosol concentrations: Is the cocktail worth the show? J. Hazard. Mater. 2010, 183, 945–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.M.; Yang, L.X.; Chen, J.M.; Mellouki, A.; Jiang, P.; Gao, Y.; Li, Y.Y.; Yang, Y.M.; Wang, W.X. Influence of fireworks displays on the chemical characteristics of PM2.5 in rural and suburban areas in Central and East China. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 578, 476–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, N.; Wang, G.; Zhu, Z.Y.; Liu, Z.L.; Tian, G.M.; Liu, Y.Q.; Gao, W.K.; Lang, J.L. Impact of fireworks burning on air quality during the Spring Festival in 2021–2022 in Linyi, a central city in the North China Plain. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 17915–17925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y.N.; Li, Q.; Zhang, K.; Li, R.; Yang, L.M.; Liu, Z.Q.; Zhang, X.J.; Wang, S.Y.; Wang, Y.J.; Chen, H.; et al. Highly time-resolved measurements of elements in PM2.5 in Changzhou, China: Temporal variation, source identification and health risks. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 853, 158450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shang, X.H.; Wang, S.B.; Zhang, R.Q.; Yuan, M.H.; Xu, Y.F.; Ying, Q. Variations of the source-specific health risks from elements in PM2.5 from 2018 to 2021 in a Chinese megacity. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2024, 15, 102092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.Z.; Zhou, X.H.; Wang, Z.; Yang, L.X.; Wang, J.; Wang, W.X. Trace elements in PM2.5 in Shandong Province: Source identification and health risk assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 621, 558–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasanbeigi, A.; Lobscheid, A.; Lu, H.Y.; Price, L.; Dai, Y. Quantifying the co-benefits of energy-efficiency policies: A case study of the cement industry in Shandong Province, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2013, 458–460, 624–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, J.L.; Yu, H.; Su, X.F.; Liu, S.H.; Li, Y.; Pan, Y.P.; Sun, J.H. Chemical composition and source apportionment of PM2.5 during Chinese Spring Festival at Xinxiang, a heavily polluted city in North China: Fireworks and health risks. Atmos. Res. 2016, 182, 176–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.X.; Shi, G.M.; Zhao, T.L.; Yang, F.M.; Zheng, X.B.; Zhang, Y.J.; Tan, Q.W. Contribution of secondary particles to wintertime PM2.5 during 2015–2018 in a major urban area of the Sichuan Basin, Southwest China. Earth Space Sci. 2020, 7, e2020EA001194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.J.; Gong, S.L.; Yu, Y.; Yu, L.J.; Wu, L.; Mao, H.J.; Song, C.B.; Zhao, S.P.; Liu, H.L.; Li, X.Y.; et al. Air pollution characteristics and their relation to meteorological conditions during 2014–2015 in major Chinese cities. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 223, 484–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.L.; Cao, F. Fine particulate matter (PM2.5) in China at a city level. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 14884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.S.; Hadiatullah, H.; Tai, P.F.; Xu, Y.L.; Zhang, X.; Schnelle-Kreis, J.; Schloter-Hai, B.; Zimmermann, R. Air pollution in Germany: Spatio-temporal variations and their driving factors based on continuous data from 2008 to 2018. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 276, 116732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.B.; Wu, L.; Xie, Y.C.; He, J.J.; Chen, X.; Wang, T.; Lin, Y.C.; Jin, T.S.; Wang, A.X.; Liu, Y.; et al. Air pollution in China: Status and spatiotemporal variations. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 227, 334–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pongpiachan, S.; Iijima, A.; Cao, J.J. Hazard Quotients, Hazard Indexes, and Cancer Risks of Toxic Metals in PM10 during Firework Displays. Atmosphere 2018, 9, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.J.; Zhang, Y.L.; Bozzetti, C.; Ho, K.F.; Cao, J.J.; Han, Y.M.; Daellenbach, K.R.; Slowik, J.G.; Platt, S.M.; Canonaco, F.; et al. High secondary aerosol contribution to particulate pollution during haze events in China. Nature 2014, 514, 218–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blitz, M.A.; Hughes, K.J.; Pilling, M.J. Determination of the high-pressure limiting rate coefficient and the enthalpy of reaction for OH+SO2. J. Phys. Chem. 2003, 107, 1971–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, W.J.; Liao, H.; Wang, H.J.; Wu, L.X. Weather conditions conducive to Beijing severe haze more frequent under climate change. Nat. Clim. Change 2017, 7, 257–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.B.; Xing, Z.Y.; Deng, J.J.; Du, K. Characterizing and sourcing ambient PM2.5 over key emission regions in China I: Water-soluble ions and carbonaceous fractions. Atmos. Environ. 2016, 135, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.J.; Zhou, R.; Wu, J.J.; Yu, Y.; Ma, Z.Q.; Zhang, L.J.; Di, Y.A. Seasonal variations and size distributions of water-soluble ions in atmospheric aerosols in Beijing, 2012. J. Environ. Sci. 2015, 34, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.S.; Yu, R.L.; Shen, H.Z.; Wang, S.; Hu, Q.C.; Cui, J.Y.; Yan, Y.; Huang, H.B.; Hu, G.R. Chemical characteristics, sources, and formation mechanisms of PM2.5 before and during the Spring Festival in a coastal city in Southeast China. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 251, 442–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.L.; Chen, X.Q.; Chen, J.S.; Zhang, F.W.; He, C.; Zhao, J.P.; Yin, L.Q. Seasonal variations and chemical compositions of PM2.5 aerosol in the urban area of Fuzhou, China. Atmos. Res. 2012, 104–105, 264–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.J.; Duan, J.; Li, Y.J.; Chen, Q.; Chen, Y.; Tang, M.J.; Yang, L.; Ni, H.Y.; Lin, C.S.; Xi, W.; et al. Effects of NH3 and alkaline metals on the formation of particulate sulfate and nitrate in wintertime Beijing. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 717, 137190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertram, T.H.; Thornton, J.A. Toward a general parameterization of N2O5 reactivity on aqueous particles: The competing effects of particle liquid water, nitrate and chloride. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2009, 9, 8351–8363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.; Fan, X.L.; Yan, C.; Kurtén, T.; Daellenbach, K.R.; Li, C.; Wang, Y.H.; Guo, Y.S.; Dada, L.; Rissanen, M.P.; et al. Unprecedented Ambient Sulfur Trioxide (SO3) Detection: Possible Formation Mechanism and Atmospheric Implications. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2020, 7, 809–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, N.; Riedel, T.; Young, C.; Bahreini, R.; Brock, C.; Dubé, W.; Kim, S.; Middlebrook, A.; Öztürk, F.; Roberts, J. N2O5 uptake coefficients and nocturnal NO2 removal rates determined from ambient wintertime measurements. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2013, 118, 9331–9350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDuffie, E.E.; Womack, C.C.; Fibiger, D.L.; Dube, W.P.; Franchin, A.; Middlebrook, A.M.; Goldberger, L.; Lee, B.H.; Thornton, J.A.; Moravek, A.; et al. On the contribution of nocturnal heterogeneous reactive nitrogen chemistry to particulate matter formation during wintertime pollution events in Northern Utah. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2019, 19, 9287–9308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.Y.; Li, Z.Q.; Wang, Q.Y.; Jin, X.A.; Yan, P.; Cribb, M.; Li, Y.N.; Yuan, C.; Wu, H.; Ren, R.M.; et al. Enhancement of secondary aerosol formation by reduced anthropogenic emissions during Spring Festival 2019 and enlightenment for regional PM2.5 control in Beijing. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2021, 21, 915–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.F.; Zheng, G.J.; Wei, C.; Mu, Q.; Zheng, B.; Wang, Z.B.; Gao, M.; Zhang, Q.; He, K.B.; Carmichael, G.; et al. Reactive nitrogen chemistry in aerosol water as a source of sulfate during haze events in China. Sci. Adv. 2016, 2, 1601530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.X.; Wang, X.M.; Liu, T.Y.; He, Q.F.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Y.L.; Song, W.; Dai, Q.W.; Chen, S.; Dong, F.Q. Secondary inorganic aerosols and aerosol acidity at different PM2.5 pollution levels during winter haze episodes in the Sichuan Basin, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 918, 170512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.F.; Zou, B.B.; He, L.Y.; Hu, M.; Prévôt, A.S.H.; Zhang, Y.H. Exploration of PM2.5 sources on the regional scale in the Pearl River Delta based on ME-2 modeling. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2018, 18, 11563–11580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, R.; Peng, X.; Lin, W.; He, L.; Wei, F.; Tang, M.; Huang, X. Trends and challenges regarding the source-specific health risk of PM2.5-bound metals in a Chinese megacity from 2014 to 2020. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 6996–7005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleeman, M.J.; Schauer, J.J.; Cass, G.R. Size and composition distribution of fine particulate matter emitted from motor vehicles. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2000, 34, 1132–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, F.L.; Liu, D.X.; Bu, T.X.; Zhang, M.Y.; Peng, J.; Ma, J.H. Assessment of pollution and health risks from exposure to heavy metals in soil, wheat grains, drinking water, and atmospheric particulate matter. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 376, 124448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, L.Y.; Huang, X.F.; Xue, L.; Hu, M.; Lin, Y.; Zheng, J.; Zhang, R.Y.; Zhang, Y.H. Submicron aerosol analysis and organic source apportionment in an urban atmosphere in Pearl River Delta of China using high-resolution aerosol mass spectrometry. J. Geophys. Res. 2011, 116, D12304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.Y.; Xing, J.; Wang, S.X.; Fu, X.; Zheng, H.T. Source-specific speciation profiles of PM2.5 for heavy metals and their anthropogenic emissions in China. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 239, 544–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.A.; Kim, H.; Kim, Y.; Heo, J.; Kim, S.W.; Jeon, K.; Yi, S.M.; Hopke, P.K. Source apportionment of PM2.5 in Seoul, South Korea and Beijing, China using dispersion normalized PMF. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 833, 155056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Q.T.; Skov, H.; Sorensen, L.L.; Jensen, B.J.; Grube, A.G.; Massling, A.; Glasius, M.; Nojgaard, J.K. Source apportionment of particles at station Nord, north East Greenland during 2008–2010 using COPREM and PMF analysis. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2013, 13, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Men, C.; Liu, R.M.; Xu, F.; Wang, Q.R.; Guo, L.J.; Shen, Z.Y. Pollution characteristics, risk assessment, and source apportionment of heavy metals in road dust in Beijing, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 612, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sijimol, M.R.; Mohan, M. Environmental impacts of perchlorate with special reference to fireworks-a review. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2014, 186, 7203–7210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.Y.; Chen, L.P.; Peng, J.H. Thermal hazard research of smokeless fireworks. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2012, 109, 1151–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Alberca, C.; García-Ruiz, C. Analytical techniques for the analysis of consumer fireworks. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2014, 56, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Yan, Y.L.; Hu, D.M.; Peng, L.; Wang, C. Chang PM2.5-bound heavy metals in a typical industrial city of Changzhi in North China: Pollution sources and health risk assessment. Atmos. Environ. 2024, 321, 120344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zheng, M.; Liu, Y.; Yan, C.Q.; Liu, J.Y.; Liu, J.M.; Cheng, Y. Exploring sources and health risks of metals in Beijing PM2.5: Insights from long-term online measurements. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 814, 151954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, Y.; Kan, H.; Xie, M.; Deng, C.; Zou, Z.; Liu, S.; Zhang, Y. First long-term and near real-time measurement of trace elements in China’s urban atmosphere: Temporal variability, source apportionment and precipitation effect. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2018, 18, 11793–11812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.; Tang, X.; Zhu, J.; Wang, Z.F.; Sun, Y.L.; Fu, P.Q.; Gao, M.; Wu, H.J.; Lu, M.M.; Wu, Q.; et al. Unbalanced emission reductions of different species and sectors in China during COVID-19 lockdown derived by multi-species surface observation assimilation. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2023, 23, 6217–6240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.J.; Li, W.S.; Li, L.; Li, M.; Zhou, Z.; Yu, J.Z.; Zhou, Y. Source Apportionment of PM2.5 Using PMF Combined Online Bulk and Single-Particle Measurements: Contribution of Fireworks and Biomass Burning. J. Environ. Sci. 2024, 136, 325–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Wang, G.X.; Bi, Y.L.; Ding, C.; Qiao, J.; Wang, L.M.; Wang, C.W.; Qiu, X.G. Impacts of fireworks on urban air quality during Spring Festivals of 2022–2024 in Shandong Province, China. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2025, 197, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.Y.; Zhang, X.R.; Lin, J.T.; Huang, J.P.; Zhao, D.; Yuan, T.G.; Huang, K.N.; Luo, Y.; Zang, Z.; Qiu, Y.A.; et al. Fugitive Road Dust PM2.5 Emissions and Their Potential Health Impacts. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 8455–8465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.L.; Qiao, L.P.; Lou, S.R.; Zhou, M.; Chen, J.M.; Wang, Q.; Tao, S.K.; Chen, C.H.; Huang, H.Y.; Li, L.; et al. PM2.5 pollution episode and its contributors from 2011 to 2013 in urban Shanghai, China. Atmos. Environ. 2015, 123, 298–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, G.; Duvall, R.; Brown, S.; Bai, S. EPA Positive Matrix Factorization (PMF) 5.0 Fundamentals and User Guide. US Environmental Protection Agency Office of Research and Development: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Amato, F.; Hopke, P.K. Source apportionment of the ambient PM2.5 acrossst. Louis using constrained positive matrix factorisation. Atmos. Environ. 2012, 46, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopke, P.K. Review of receptor modeling methods for source apportionment. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 2016, 66, 237–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wu, H.; Wang, Q.; Yang, M.; Li, F.; Sun, Y.; Qian, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, C. Chemical partitioning of fine particle-bound metals on haze-fog and non-haze-fog days in Nanjing, China and its contribution to human health risks. Atmos. Res. 2017, 183, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Cheng, R.; Jing, M.; Yang, L.; Li, Y.; Chen, Q.; Chen, Y.; Yan, J.; Lin, C.; Wu, Y.; et al. Source-specific health risk analysis on particulate trace elements: Coal combustion and traffic emission as major contributors in wintertime Beijing. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 10967–10974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Song, W.; Yang, X.; Fan, M. Specific sources of health risks caused by size-resolved PM-bound metals in a typical coal-burning city of northern China during the winter haze event. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 734, 138651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ma, Q.; Zhao, G.; Cheng, K.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, R.; Gu, L.; Xue, J.; Feng, W.; Zhou, J.; Shen, X.; et al. Increased PM2.5 Caused by Enhanced Fireworks Burning and Secondary Aerosols in a Forested City of North China During the 2023–2025 Spring Festivals. Toxics 2025, 13, 1009. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121009

Ma Q, Zhao G, Cheng K, Wu Y, Zhang R, Gu L, Xue J, Feng W, Zhou J, Shen X, et al. Increased PM2.5 Caused by Enhanced Fireworks Burning and Secondary Aerosols in a Forested City of North China During the 2023–2025 Spring Festivals. Toxics. 2025; 13(12):1009. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121009

Chicago/Turabian StyleMa, Qingxia, Guoqing Zhao, Kaixin Cheng, Yunfei Wu, Renjian Zhang, Lei Gu, Jing Xue, Wanfu Feng, Jiliang Zhou, Xinzhi Shen, and et al. 2025. "Increased PM2.5 Caused by Enhanced Fireworks Burning and Secondary Aerosols in a Forested City of North China During the 2023–2025 Spring Festivals" Toxics 13, no. 12: 1009. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121009

APA StyleMa, Q., Zhao, G., Cheng, K., Wu, Y., Zhang, R., Gu, L., Xue, J., Feng, W., Zhou, J., Shen, X., & Liu, D. (2025). Increased PM2.5 Caused by Enhanced Fireworks Burning and Secondary Aerosols in a Forested City of North China During the 2023–2025 Spring Festivals. Toxics, 13(12), 1009. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121009