Assessment of Estrogenic and Genotoxic Activity in Wastewater Using Planar Bioassays

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Wastewater Samples

2.2. Chemicals and Materials

2.3. Sample Preparation, Buffer, Substrate, Ampicillin and Positive Control Solution

2.4. Preparation of Bacterial and Yeast Cultures

2.5. Workflow of the Planar SOS-Umu-C Genotoxicity Assays

2.6. Workflow of the Planar Yeast Estrogen Screen (YES) Assay

2.7. Calculation of Reference Compound Biological Equivalent Concentration

3. Results

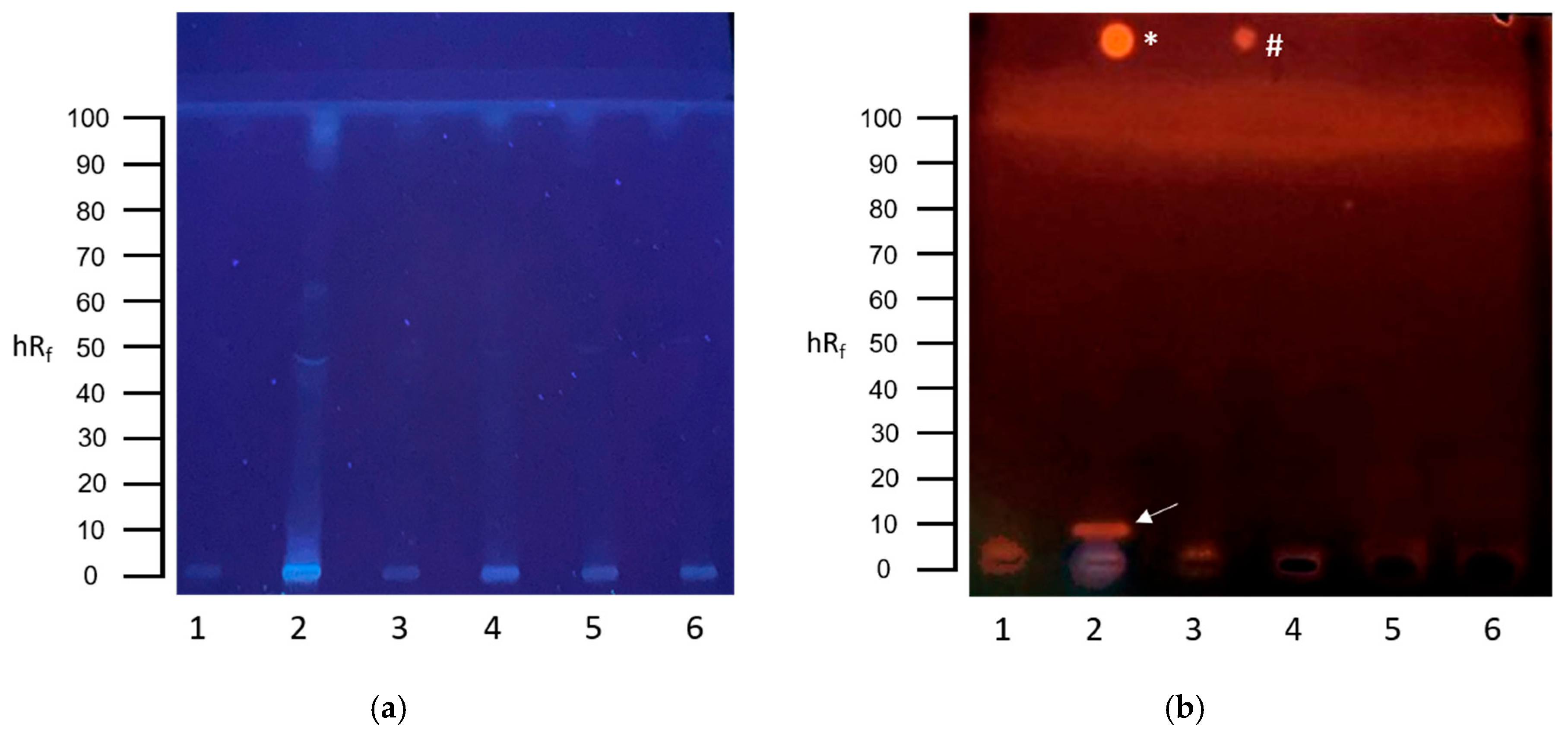

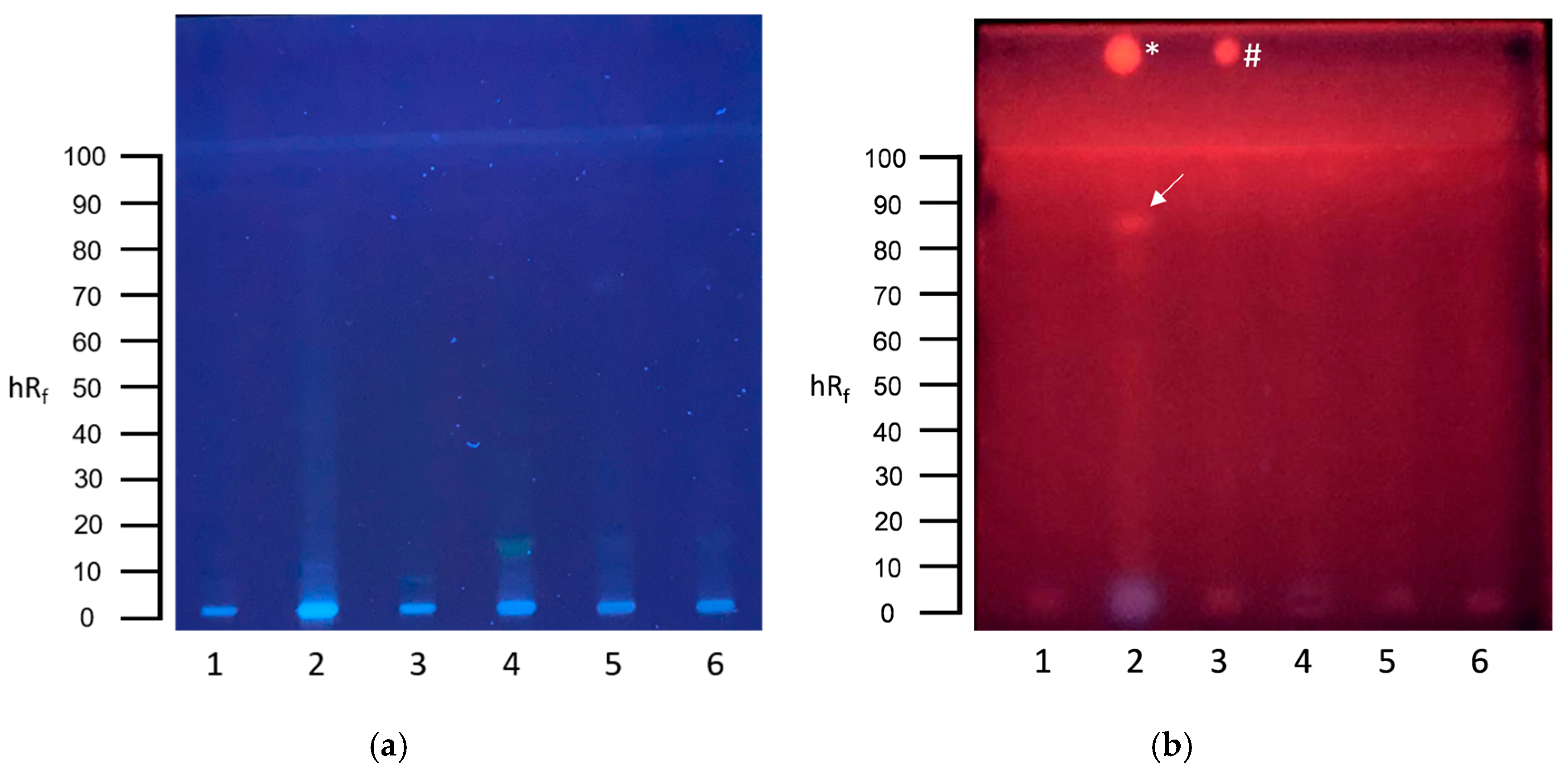

3.1. Screening for Genotoxins in Communal Wastewater with the Planar SOS-Umu-C Assay

3.2. Screening for Genotoxins in Hospital Wastewater with the Planar SOS-Umu-C Assay

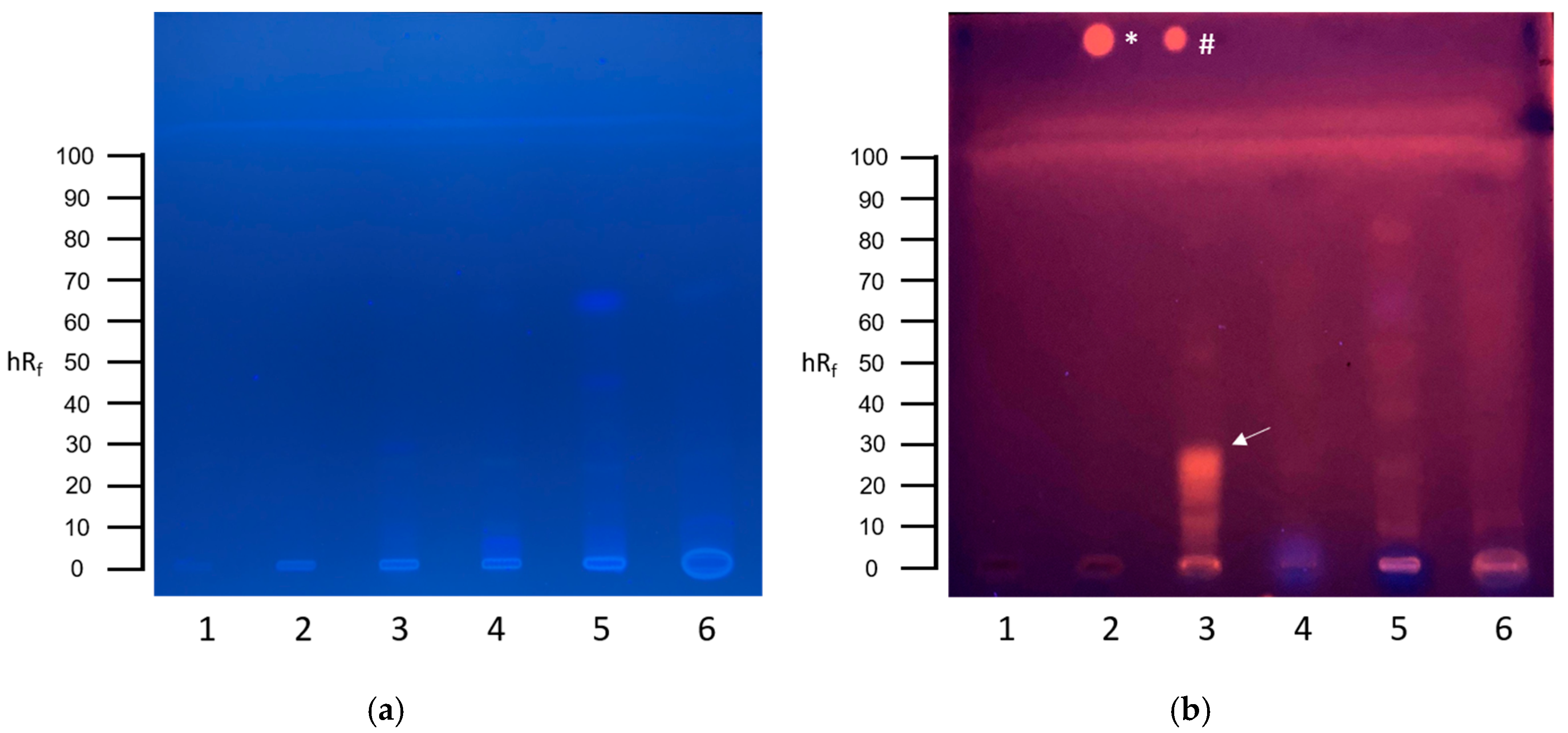

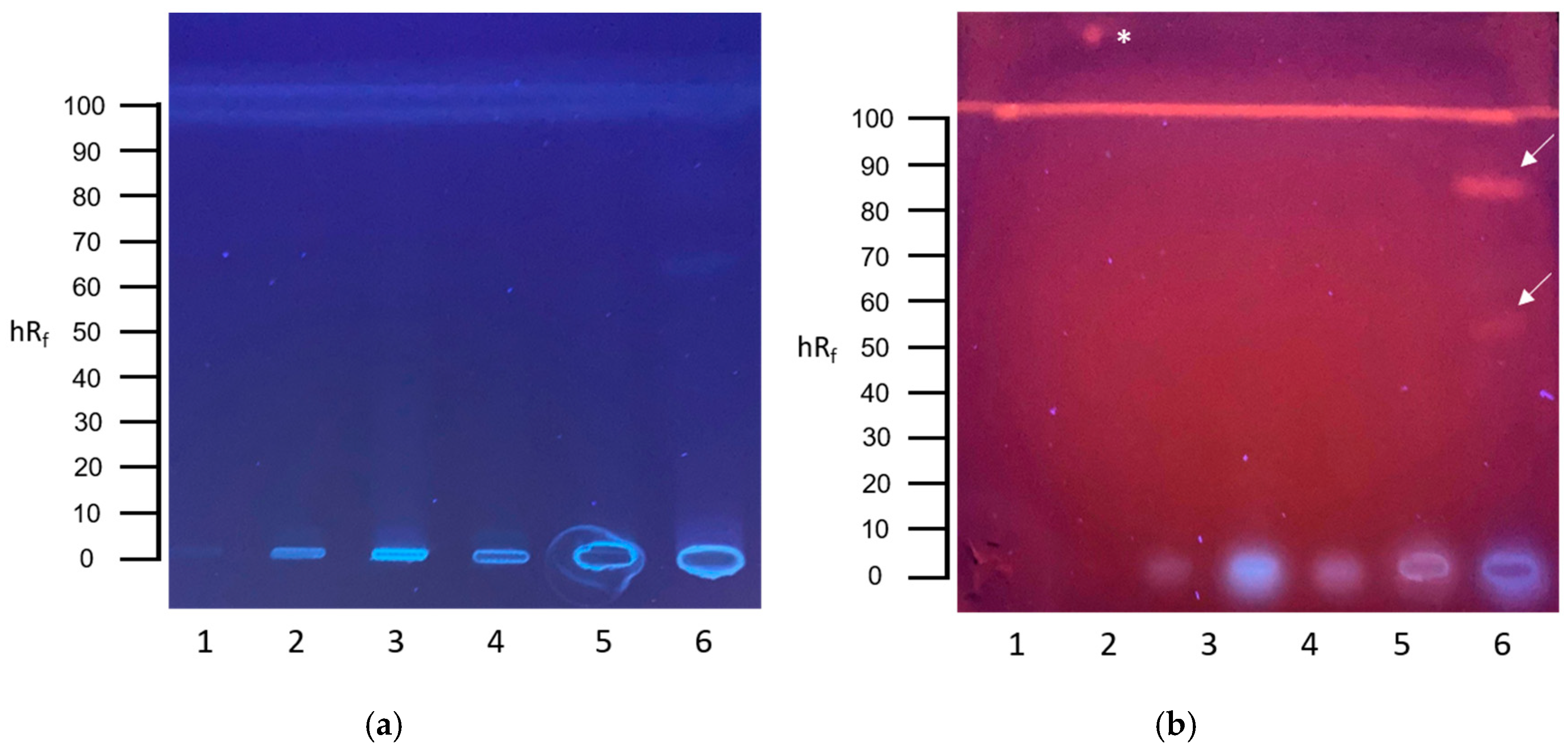

3.3. Screening for Estrogenic Substances in Communal Wastewater with the Planar YES Assay

3.4. Screening for Estrogenic Substances in Hospital Wastewater with the Planar YES Assay

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AUC | Area under the curve |

| BEQ | Biological equivalence concentration |

| E2 | 17β-estradiol |

| ECs | Estrogenic compounds |

| GC-MS | Gas chromatography–mass spectrometry |

| HPTLC | High-performance thin-layer chromatography |

| LC-MS | Liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry |

| LLE | Liquid–liquid extraction |

| SPE | Solid-phase extraction |

| TLC | Thin layer chromatography |

| YAS | Yeast androgen screen |

| YES | Yeast estrogen screen |

| 4-NQO | 4-nitroquinoline-1-oxide |

References

- Snyder, S.A.; Westerhoff, P.; Yoon, Y.; Sedlak, D.L. Pharmaceuticals, Personal Care Products, and Endocrine Disruptors in Water: Implications for the Water Industry. Environ. Eng. Sci. 2003, 20, 449–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baronti, C.; Curini, R.; D’Ascenzo, G.; Di Corcia, A.; Gentili, A.; Samperi, R. Monitoring Natural and Synthetic Estrogens at Activated Sludge Sewage Treatment Plants and in a Receiving River Water. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2000, 34, 5059–5066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jobling, S.; Nolan, M.; Tyler, C.R.; Brighty, G.; Sumpter, J.P. Widespread Sexual Disruption in Wild Fish. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1998, 32, 2498–2506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidd, K.A.; Blanchfield, P.J.; Mills, K.H.; Palace, V.P.; Evans, R.E.; Lazorchak, J.M.; Flick, R.W. Collapse of a Fish Population after Exposure to a Synthetic Estrogen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 8897–8901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liney, K.E.; Hagger, J.A.; Tyler, C.R.; Depledge, M.H.; Galloway, T.S.; Jobling, S. Health Effects in Fish of Long-Term Exposure to Effluents from Wastewater Treatment Works. Environ. Health Perspect. 2006, 114, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harries, J.E.; Janbakhsh, A.; Jobling, S.; Matthiessen, P.; Sumpter, J.P.; Tyler, C.R. Estrogenic Potency of Effluent from Two Sewage Treatment Works in the United Kingdom. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 1999, 18, 932–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purdom, C.E.; Hardiman, P.A.; Bye, V.J.; Eno, N.C.; Tyler, C.R.; Sumpter, J.P. Estrogenic Effects of Effluents from Sewage Treatment Works. Chem. Ecol. 1994, 8, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, M.; Deoraj, A.; Felty, Q.; Roy, D. Environmental Estrogen-like Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals and Breast Cancer. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2017, 457, 89–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibarluzea, J.M.; Fernández, M.F.; Santa-Marina, L.; Olea-Serrano, M.F.; Rivas, A.M.; Aurrekoetxea, J.J.; Expósito, J.; Lorenzo, M.; Torné, P.; Villalobos, M.; et al. Breast Cancer Risk and the Combined Effect of Environmental Estrogens. Cancer Causes Control 2004, 15, 591–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joffe, M. Are Problems with Male Reproductive Health Caused by Endocrine Disruption? Occup. Environ. Med. 2001, 58, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamanti-Kandarakis, E.; Bourguignon, J.P.; Giudice, L.C.; Hauser, R.; Prins, G.S.; Soto, A.M.; Zoeller, R.T.; Gore, A.C. Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals: An Endocrine Society Scientific Statement. Endocr. Rev. 2009, 30, 293–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenberg, L.N.; Colborn, T.; Hayes, T.B.; Heindel, J.J.; Jacobs, D.R.; Lee, D.H.; Shioda, T.; Soto, A.M.; vom Saal, F.S.; Welshons, W.V.; et al. Hormones and Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals: Low-Dose Effects and Nonmonotonic Dose Responses. Endocr. Rev. 2012, 33, 378–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnamurthi, K.; Saravana Devi, S.; Hengstler, J.G.; Hermes, M.; Kumar, K.; Dutta, D.; Muhil Vannan, S.; Subin, T.S.; Yadav, R.R.; Chakrabarti, T. Genotoxicity of Sludges, Wastewater and Effluents from Three Different Industries. Arch. Toxicol. 2008, 82, 965–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilroy, È.A.M.; Kleinert, C.; Lacaze, É.; Campbell, S.D.; Verbaan, S.; André, C.; Chan, K.; Gillis, P.L.; Klinck, J.S.; Gagné, F.; et al. In Vitro Assessment of the Genotoxicity and Immunotoxicity of Treated and Untreated Municipal Effluents and Receiving Waters in Freshwater Organisms. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 64094–64110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krawczyk, E.; Piñero-García, F.; Ferro-García, M.A. Discharges of Nuclear Medicine Radioisotopes in Spanish Hospitals. J. Environ. Radioact. 2013, 116, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, A.; Alder, A.C.; Koller, T.; Widmer, R.M. Identification of Fluoroquinolone Antibiotics as the Main Source of UmuC Genotoxicity in Native Hospital Wastewater. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 1998, 17, 377–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolibois, B.; Guerbet, M. Hospital Wastewater Genotoxicity. Ann. Occup. Hyg. 2006, 50, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, J.S.; Cabral, T.M.; Ferreira, D.N.; Agnez-Lima, L.F.; Batistuzzo de Medeiros, S.R. Genotoxicity Assessment in Aquatic Environment Impacted by the Presence of Heavy Metals. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2010, 73, 320–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ternes, T.A.; Stumpf, M.; Mueller, J.; Haberer, K.; Wilken, R.D.; Servos, M. Behavior and Occurrence of Estrogens in Municipal Sewage Treatment Plants—I. Investigations in Germany, Canada and Brazil. Sci. Total Environ. 1999, 225, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrovic, M.; Eljarrat, E.; Lopez De Alda, M.J.; Barceló, D. Endocrine Disrupting Compounds and Other Emerging Contaminants in the Environment: A Survey on New Monitoring Strategies and Occurrence Data. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2004, 378, 549–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gros, M.; Petrović, M.; Barceló, D. Development of a Multi-Residue Analytical Methodology Based on Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) for Screening and Trace Level Determination of Pharmaceuticals in Surface and Wastewaters. Talanta 2006, 70, 678–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metcalfe, C.D.; Kleywegt, S.; Letcher, R.J.; Topp, E.; Wagh, P.; Trudeau, V.L.; Moon, T.W. A Multi-Assay Screening Approach for Assessment of Endocrine-Active Contaminants in Wastewater Effluent Samples. Sci. Total Environ. 2013, 454–455, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council of the European Union. Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council Concerning Urban Wastewater Treatment (Recast)—Letter to the Chair of the European Parliament Committee on the Environment, Public Health and Food Safety (ENVI); Council of the European Union: Brussel, Belgium, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, D.; Marin-Kuan, M.; Debon, E.; Serrant, P.; Cottet-Fontannaz, C.; Schilter, B.; Morlock, G.E. Detection of Low Levels of Genotoxic Compounds in Food Contact Materials Using an Alternative HPTLC-SOS-Umu-C Assay. ALTEX 2021, 38, 387–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morlock, G.E.; Zoller, L. Fast Unmasking Toxicity of Safe Personal Care Products. J. Chromatogr. A 2025, 1752, 465886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehl, A.; Seiferling, S.; Morlock, G.E. Non-Target Estrogenic Screening of 60 Pesticides, Six Plant Protection Products, and Tomato, Grape, and Wine Samples by Planar Chromatography Combined with the Planar Yeast Estrogen Screen Bioassay. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2024, 416, 701–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riegraf, C.; Reifferscheid, G.; Moscovici, L.; Shakibai, D.; Hollert, H.; Belkin, S.; Buchinger, S. Coupling High-Performance Thin-Layer Chromatography with a Battery of Cell-Based Assays Reveals Bioactive Components in Wastewater and Landfill Leachates. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 214, 112092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sing, L.; Schwack, W.; Göttsche, R.; Morlock, G.E. 2LabsToGo─Recipe for Building Your Own Chromatography Equipment Including Biological Assay and Effect Detection. Anal. Chem. 2022, 94, 14554–14564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fichou, D.; Morlock, G.E. QuanTLC, an Online Open-Source Solution for Videodensitometric Quantification. J. Chromatogr. A 2018, 1560, 78–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahagi, T.; Nagao, M.; Seino, Y.; Matsushima, T.; Sugimura, T.; Okada, M. Mutagenicities of N-Nitrosamines on Salmonella. Mutat. Res.—Fundam. Mol. Mech. Mutagen. 1977, 48, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salamanca-Pinzón, S.G.; Camacho-Carranza, R.; Hernández-Ojeda, S.L.; Frontana-Uribe, B.A.; Espitia-Pinzón, C.I.; Espinosa-Aguirre, J.J. Correlation of the Genotoxic Activation and Kinetic Properties of Salmonella enterica Serovar Typhimurium Nitroreductases SnrA and Cnr with the Redox Potentials of Nitroaromatic Compounds and Quinones. Mutagenesis 2010, 25, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holbrook, R.D.; Novak, J.T.; Grizzard, T.J.; Love, N.G. Estrogen Receptor Agonist Fate during Wastewater and Biosolids Treatment Processes: A Mass Balance Analysis. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2002, 36, 4533–4539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Windisch, M.; Rieser, V.; Kittinger, C. Assessment of Estrogenic and Genotoxic Activity in Wastewater Using Planar Bioassays. Toxics 2025, 13, 936. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13110936

Windisch M, Rieser V, Kittinger C. Assessment of Estrogenic and Genotoxic Activity in Wastewater Using Planar Bioassays. Toxics. 2025; 13(11):936. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13110936

Chicago/Turabian StyleWindisch, Markus, Valentina Rieser, and Clemens Kittinger. 2025. "Assessment of Estrogenic and Genotoxic Activity in Wastewater Using Planar Bioassays" Toxics 13, no. 11: 936. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13110936

APA StyleWindisch, M., Rieser, V., & Kittinger, C. (2025). Assessment of Estrogenic and Genotoxic Activity in Wastewater Using Planar Bioassays. Toxics, 13(11), 936. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13110936