Distribution Characteristics of Low-Molecular-Weight Organic Acids in Reclaimed Soil Filled with Fly Ash: A Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Overview of Study Area

2.2. Sample Collection and Pretreatments

2.3. Analytical Instruments and Reagents

2.4. Organic Acid Determination Method and Liquid Chromatographic Conditions

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. Contents and Species of Low-Molecular-Weight Organic Acids in Reclaimed Soil

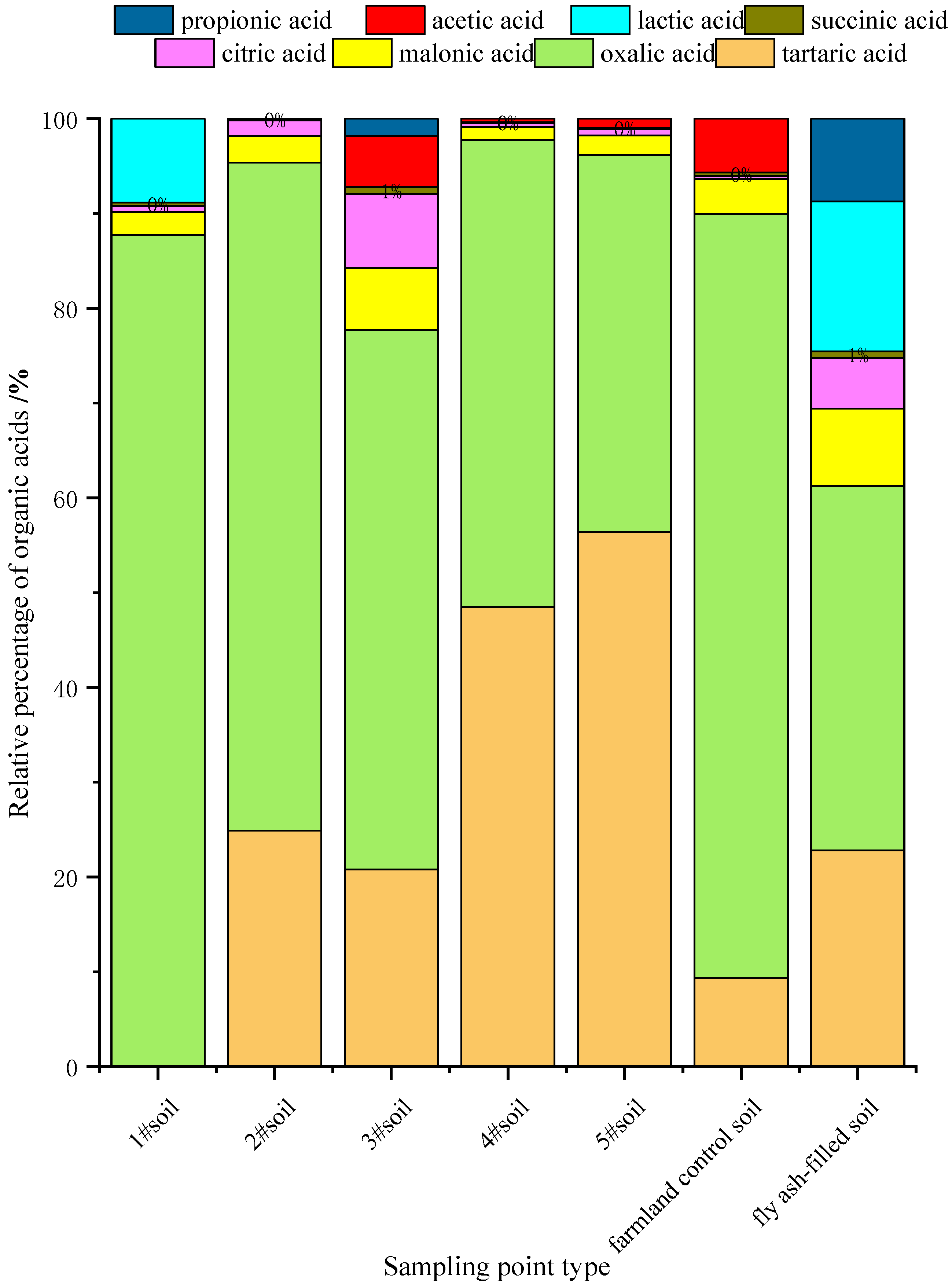

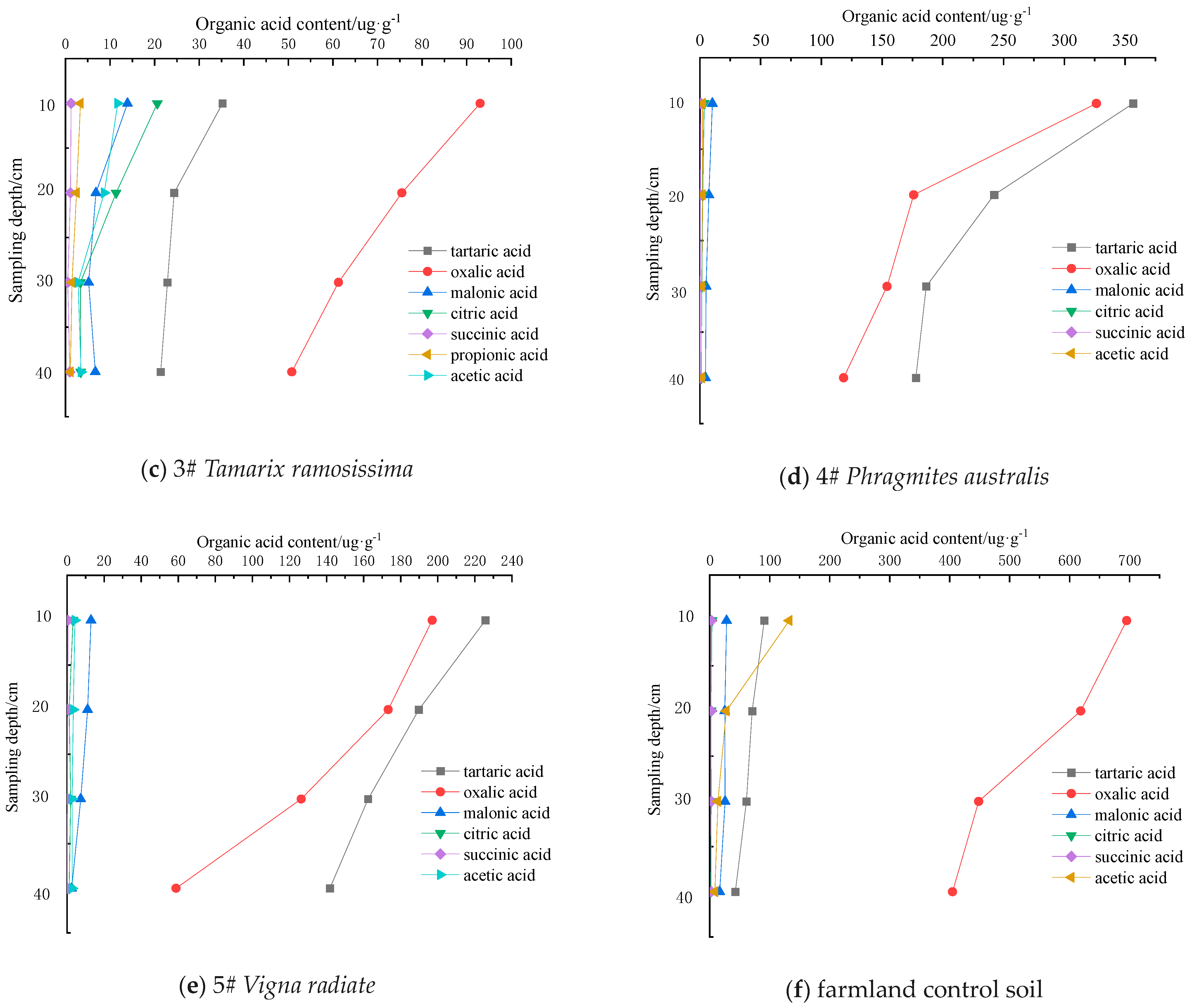

3.2. Characteristics of Low-Molecular-Weight Organic Acid Contents in Reclaimed Soil

3.3. Cluster Analysis of Low-Molecular-Weight Organic Acids in Reclaimed Soil

3.4. Correlations between Soil Nutrients and Organic Acids in Reclaimed Soil

4. Discussion

4.1. Compositions and Sources of Organic Acids in Reclaimed Soil

4.2. Compositions and Sources of Organic Acids in Fly Ash Material

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- Under constant climatic conditions and soil physicochemical properties, eight LMWOA types were detected in the reclaimed soil, while seven types were detected in the fly ash−filled soil. However, no LMWOAs were detected in the fresh fly ash from the power plant. According to the obtained results, the use of fresh fly ash in the reclamation process had a slight contribution to the soil organic acid content. However, the applied fly ash slightly increased the available potassium and phosphorus contents in the soil, contributing to the formation of LMWOAs.

- (2)

- The LMWOA contents in the reclaimed soil followed the order of oxalic acid > tartaric acid > succinic acid > lactic acid > acetic acid > citric acid > propionic acid > succinic acid. Oxalic and succinic acids exhibited the highest and lowest contents of 1445.79 and 6.50 µg·g−1, respectively. The total LMWOA contents at the soil sampling points followed the order of farmland control soil > 1# (Triticum aestivum) > 4# (Phragmites australis) > 5# (Vigna radiata) > 2# (Sorghum bicolor) > 3# (Tamarix ramosissima) > fly ash−filled soil. The LMWOA contents in the reclaimed soil decreased with increasing soil depth, showing significant differences between the 0–20 and the 20–40 cm soil layers.

- (3)

- The contents of the nutrient indicators in the reclaimed soils, including organic matter, available phosphorus, available potassium, and alkali−hydrolyzable nitrogen, were low. In contrast, the fly ash had relatively high available potassium and phosphorus contents, thereby increasing the reclaimed soil content to some extent. The results showed negative correlations between the reclaimed soil pH values and LMWOA contents (except tartaric acid). The available potassium content exhibited a strong significant positive correlation with the citric acid content, while the soil organic matter and alkali−hydrolyzable nitrogen content showed strong significant positive correlations with the lactic succinic acid content, respectively. On the other hand, the available phosphorus content showed strong significant positive correlations with the tartaric, succinic, and acetic acid content (p < 0.01). Therefore, the LMWOA contents in reclaimed soils can be improved by regulating the contents of soil nutrient indicators, thereby promoting the restoration of ecological functions of the rhizosphere in reclamation soil areas.

- (4)

- The types and contents of the detected LMWOAs in the soil are influenced by several factors, including soil type, soil nutrient status, pH value, temperature, moisture content, microbial activity, and organic matter type and content. On the other hand, the LMWOAs are also affected by analytical−related factors, including detection instrument, detection method, and organic acid standard type. Therefore, the eight detected LMWOAs in the reclaimed soil in this study do not represent all soil LMWOA types. However, they can reflect the main characteristics of organic acid occurrence. Hence, future comprehensive studies on LMWOAs in reclaimed soils are required.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tang, J.; Wang, Y.; Fu, Y.; Huang, M.; Qu, P.; Guan, Q.Z. Study on activation of nickel in soil by low molecular weight organic acids. Anhui Agric. Sci. 2021, 49, 87–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alimu, A.; Cong, X.H.; Xia, X.Y.; Xi, L.; Wang, W.X. Chatracteristics of soil nutrient under different land use patterns. Xinjiang Agric. Sci. 2022, 59, 925–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.Y.; Quan, W.X.; Li, C.C.; Pan, Y.N.; Xie, L.J.; HAO, J.T.; Gao, Y.D. Distribution Characteristics of Low Molecular Weight Organic Acids in Soil of Wild Rhododendron Forest. Sci. Silvae Sin. 2021, 57, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeleke, R.; Nwangburuka, C.; Oboirien, B. Origins, roles and fate of organic acids in soils. South Afr. J. Bot. 2017, 108, 393–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.B.; Li, C.X.; Zhang, C.; Wang, D.Y.; Wang, Y.M. Nutrients uptake and low molecular weight organic acids secretion in the rhizosphere of Cynodon dactylon facilitate mercury activation and migration. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 441, 129961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña, A. A comprehensive review of recent research concerning the role of low molecular weight organic acids on the fate of organic pollutants in soil. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 434, 128875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, W.B.; Huang, L.; Yang, Z.H.; Zhao, F.P. Effects of organic acids on heavy metal release or immobilization in contaminated soil. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2022, 32, 1277–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oburger, E.; Kirk, G.J.D.; Wenzel, W.W.; Puschenreiter, M.; Jones, D.L. Interactive effects of organic acids in the rhizosphere. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2009, 41, 449–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Q.Q.; Bian, C.M.; Wang, J.W. Detoxification of organic acid against pollution rice plant for Pb and Cd. J. Anhui Agric. Sci. 2009, 37, 6567–6569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waithaisong, K.; Robin, A.; Martin, A.; Clairotte, M.; Villeneuve, M.; Plassard, C. Quantification of organic P and low-molecular-weight organic acids in ferralsol soil extracts by ion chromatography. Geoderma 2015, 257–258, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Shi, Y.; Jiang, T.; Wei, S.Q. Effects of organic acids on form transformation and availability of soil lnorganic phosphorous in the water- fluctuation zone of three gorge reservoir area. J. Soil Water Conserv. 2015, 29, 272–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.B.; Zhao, X.M.; Li, Y.H.; Chen, X. Effects of LMWOAs of Iris pseudacorus L. Rhizosphere on Ammonia Nitrogen Adsorption of Soil. J. Northeast. Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2020, 41, 269–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.S.; Rezwan, F.; Kashem, M.A.; Moniruzzaman, M.; Parvin, A.; Das, S.; Hu, H.Q. Impact of a phosphate compound on plant metal uptake when low molecular weight organic acids are present in artificially contaminated soils. Environ. Adv. 2024, 15, 100468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Z.H.; Zhang, S.R.; Cao, Y.R.; Zhong, Q.M.; Liu, X.M. Study on the removal of heavy metals in soil by low molecular weight organic acid and organic acid polymer. J. Agro-Environ. Sci. 2018, 37, 1660–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuo, S.; Yang, J.H.; Yan, S.W.; Yan, Y.T.; Zhang, L.Y.; Ye, W.L. Research progress on the effects of rhizosphere organic acids on the chemical behavior and bioavailability of heavy metals in soil. J. Biol. 2022, 39, 103–106+124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, R.; Li, J.S.; Luo, Z.L.; Wu, X.P.; Zhao, C.Y.; Tang, B. Influence of Soil Microbial and Organic Acids on Soil Respiration Rate. J. Soil Water Conserv. 2010, 24, 242–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q. Research status of fly ash utilization and its application in environmental protection. China Resour. Compr. Util. 2020, 38, 41–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.M.; Zheng, J.L.; Zhu, Y.T. Effect of particle characteristics of fly ash on hydration properties of recycled concrete. J. Fuzhou Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2021, 49, 238–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, S.; Thai, Q.; Ho, L. Properties of fine-grained concrete containing fly ash and bottom ash. Mag. Civ. Eng. 2021, 107, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.Y.; Li, X.J.; Zhao, Y.L.; Cai, D.S.; Wu, Z.L.; Gao, F. The influence of different reclamation modes on soil nutrient in coal mine plots. J. Shandong Agric. Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2017, 48, 186–191. [Google Scholar]

- Ju, T.Y.; Han, S.Y.; Yuan, M.; Jiang, J.G. High-End reclamation of coal fly ash focusing on elemental extraction and synthesis of porous materials. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 6894–6911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.P. Application of hierarchical cluster analysis in environmental monitoring data analysis. Resour. Econ. Environ. Prot. 2020, 224, 74–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.H.; Chen, F.L.; Zhang, Z.G.; Deng, Y.Q.; Fang, C.; Zhang, Z.L. Nutrient analysis and evaluation of agricultural land with high water level in Huaihe River Basin. J. Anhui Univ. Sci. Technol. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2022, 42, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Z.Q.; Qi, J.H.; Si, J.T. Physical and chemical properties of reclaimed soil filled with fly ash. J. China Coal Soc. 2002, 27, 639–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Dai, L.Y.; Xiao, S.Z.; Tai, Z.Q.; Lan, J.C.; Xiao, H. Vertical distribution characteristics of soil organic carbon and nutrients in plough layer of subtropical dolomite karst area. Ecol. Sci. 2023, 42, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, F.J.; Zhang, W.; Liang, Y.M.; Wang, K.L.; Jin, Z.J. Seasonal changes of soil organic acid concentrations in relation to available N and P at different stages of vegetation restoration in a karst ecosystem. Chin. J. Ecol. 2020, 39, 1112–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.F.; Li, F.S.; Luo, W.G.; Huang, T. Effects of ridge irrigation and nitrogen reduction on paddy field CH4 emission, soil organic acid content and expression of enzyme encoding genes. J. South China Agric. Univ. 2024, 45, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.M.; Yang, F.; Han, P.L.; Zhou, W.L.; Wang, J.H.; Yan, Q.F.; Lin, J.X. Research progress on the mechanism of root exudates in response to abiotic stresses. Chin J. Appl. Env. Biol. 2022, 28, 1384–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X. Characteristics and Sources of Organic Acids in Atmospheric Deposition at Mount Lu. Master’s Thesis, Shandong University, Jinan, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.Y.; Zhao, K. Characteristics of low molecular weight organic acids in roots, stems and leaves, and root exudates in four species seedlings. Acta Bot. Boreali-Occident. Sin. 2014, 34, 1002–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Mou, F.L.; Wang, X.J.; Zu, Y.Q. Effect of low molecular weight organic acids on plant absorption and accumulation of heavy metals:a review. Jiangsu Agric. Sci. 2021, 49, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Zhou, B.H.; Ma, W.Z.; Yang, L.M. The lnfluence of different environmental stresses on root-exuded organic acids: A review. Soils 2016, 48, 235–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veneklaas, E.J.; Stevens, J.; Cawthray, G.R.; Turner, S.; Grigg, A.M.; Lambers, H. Chickpea and white lupin rhizosphere carboxylates vary with soil properties and enhance phosphorus uptake. Plant Soil 2003, 248, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, L.; He, Y.M.; Wang, J.X.; Li, B.; Jiang, M.; Li, Y. Lead accumulation and low-molecular-weight organic acids secreted by roots in Sonchus asper L. -Zea mays L. intercropping system. Chin. J. Eco-Agric. 2020, 28, 867–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.H.; Zhang, Z.G.; Chen, Y.C.; An, S.K.; Zhang, L.; Chen, F.L.; Ma, C.N.; Cai, W.Q. Adsorption and desorption of Cd in reclaimed soil under the influence of humic acid: Characteristics and mechanisms. Int. J. Coal Sci. Technol. 2022, 9, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.B.; Li, L.J.; Zhang, Y.L. Comprehensive evaluation of saline-alkali tolerance and comparison of rhizosphere soil organic acid content at rapeseed seedling stage. Crops 2022, 206, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.B.; Ma, R.; Yang, D.; Liu, X.P.; Song, J.F. Organic acids secreted from plant roots under soil stress and their effects on ecological adaptability of plants. Agric. Sci. Technol. 2014, 15, 1167–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, T.T.; Bi, J.J. Effect of fly ash based soil water retention conditioner on winter wheat. Bull. Agric. Sci. Technol. 2021, 591, 53–59. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S.Q.; Dang, T.H.; Qi, R.S. Activation effects of low molecular weight organic acids on phosphorus in soils with different fertility. Agric. Res. Arid Areas 2012, 30, 60–64. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, W.; Xu, G.Y.; Yu, H.L.; Xie, N.; Gao, D.T.; Si, P.; Wu, G.L. Response of soil microbial community and nutrients to low molecular weight organic acids in a Hongbaoshi pear orchard. J. Fruit Sci. 2023, 40, 481–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Tang, B.L.; Wang, H.T. Effects of glyphosate in soil on the growth of Poncirus aurantii seedlings, organic acids, enzyme activities and microorganisms in rhizosphere soil. Fruit Trees South. China 2022, 51, 30–34+39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Yang, Y.B.; Liu, J.; Xin, H.J.; Chen, J.; Xu, S.; Liu, X.J.; Hou, X. Present Status and Prospect of Fly Ash Utilization in China. Energy Res. Manag. 2022, 1, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sampling Point | 1# | 2# | 3# | 4# | 5# | 6# |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Botanical name | Triticum aestivum L. | Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench | Tamarix ramosissima | Phragmites australis (Cav.) Trin. ex Steud. | Vigna radiate (L.) Wilczek | Farmland control soil |

| Growth situation | Vigorous | Vigorous | Adequate | Vigorous | Adequate | No planting |

| No. | Sample | Statistics Index | Low-Molecular-Weight Organic Acid Species | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tartaric Acid | Oxalic Acid | Malonic Acid | Citric Acid | Succinic Acid | Lactic Acid | Acetic Acid | Propionic Acid | |||

| 1 | 1# triticum aestivum | Mean | 146.43 | 347.81 | 9.52 | 2.44 | 1.46 | 35.07 | ND | ND |

| Standard deviation | 12.85 | 86.64 | 5.06 | 1.29 | 0.16 | 24.65 | / | / | ||

| Coefficient of variation (%) | 8.76 | 24.91 | 53.15 | 52.87 | 10.96 | 70.29 | / | / | ||

| Maximum | 169.97 | 455.88 | 16.70 | 4.17 | 1.75 | 63.03 | / | / | ||

| Minimum | 120.81 | 263.41 | 5.97 | 1.43 | 0.91 | 9.36 | / | / | ||

| 2 | 2# sorghum bicolor | Mean | 33.24 | 94.15 | 3.78 | 2.17 | 0.24 | ND | ND | ND |

| Standard deviation | 0.16 | 141.60 | 1.05 | 0.36 | 0.13 | / | / | / | ||

| Coefficient of variation (%) | 0.48 | 110.40 | 27.78 | 16.59 | 54.17 | / | / | / | ||

| Maximum | 51.86 | 312.21 | 9.99 | 2.87 | 0.41 | / | / | / | ||

| Minimum | 24.42 | 29.01 | 1.09 | 1.54 | 0.15 | / | / | / | ||

| 3 | 3# tamarix ramosissima | Mean | 25.96 | 70.95 | 8.18 | 9.71 | 0.98 | ND | 6.69 | 2.25 |

| Standard deviation | 3.42 | 2.85 | 0.91 | 4.19 | 0.05 | / | 2.23 | 0.24 | ||

| Coefficient of variation (%) | 13.17 | 4.02 | 11.12 | 43.15 | 5.10 | / | 33.33 | 10.67 | ||

| Maximum | 39.13 | 95.88 | 19.04 | 32.26 | 1.33 | / | 12.99 | 3.69 | ||

| Minimum | 13.39 | 50.15 | 4.16 | 2.55 | 0.39 | / | 1.38 | 1.12 | ||

| 4 | 4# phragmites australis | Mean | 240.76 | 244.34 | 6.86 | 2.03 | 0.51 | ND | 1.75 | ND |

| Standard deviation | 65.08 | 156.73 | 1.31 | 0.99 | 0.26 | / | 0.41 | / | ||

| Coefficient of variation (%) | 27.03 | 64.14 | 19.10 | 48.77 | 50.98 | / | 23.43 | / | ||

| Maximum | 441.60 | 467.30 | 12.57 | 3.59 | 0.98 | / | 2.20 | / | ||

| Minimum | 141.45 | 153.85 | 1.22 | 1.06 | 0.20 | / | 1.33 | / | ||

| 5 | 5# vigna radiata | Mean | 189.18 | 133.51 | 6.92 | 2.27 | 0.34 | ND | 3.27 | ND |

| Standard deviation | 27.02 | 75.59 | 3.36 | 0.88 | 0.08 | / | 0.71 | / | ||

| Coefficient of variation (%) | 14.28 | 56.61 | 48.55 | 38.77 | 23.53 | / | 21.71 | / | ||

| Maximum | 238.94 | 199.93 | 12.95 | 4.12 | 0.53 | / | 4.16 | / | ||

| Minimum | 141.75 | 48.76 | 1.34 | 1.14 | 0.18 | / | 2.75 | / | ||

| 6 | Farmland control soil | Mean | 60.81 | 522.35 | 23.78 | 2.24 | 2.39 | ND | 36.65 | ND |

| Standard deviation | 4.35 | 86.61 | 3.24 | 1.34 | 0.09 | / | 65.49 | / | ||

| Coefficient of variation (%) | 7.15 | 16.58 | 13.62 | 59.82 | 3.76 | / | 128.69 | / | ||

| Maximum | 90.96 | 695.34 | 33.77 | 4.17 | 2.73 | / | 132.46 | / | ||

| Minimum | 38.77 | 390.18 | 14.08 | 1.43 | 2.17 | / | 1.48 | / | ||

| 7 | Fly ash-filled soil | Mean | 19.43 | 32.68 | 6.96 | 4.56 | 0.58 | 13.45 | ND | 7.43 |

| 8 | Power plant fly ash fresh | Mean | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| No. | Land Types | Solum (cm) | pH | Organic Matter (g·kg−1) | Available Potassium (mg·kg−1) | Available Phosphorus (mg·kg−1) | Alkali−Hydrolyzable Nitrogen (mg·kg−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Reclamation area soil | 0–10 | 7.27 ± 0.22 | 24.73 ± 0.11 | 121.77 ± 0.21 | 9.40 ± 0.15 | 60.36 ± 1.70 |

| 10–20 | 7.47 ± 0.17 | 19.56 ± 0.03 | 120.27 ± 0.04 | 7.29 ± 0.34 | 56.94 ± 0.32 | ||

| 20–30 | 7.80 ± 0.02 | 17.13 ± 0.38 | 118.13 ± 0.35 | 5.89 ± 0.09 | 48.87 ± 0.77 | ||

| 30–40 | 7.82 ± 0.11 | 13.01 ± 0.21 | 76.22 ± 0.01 | 5.58 ± 0.01 | 42.33 ± 0.15 | ||

| 2 | Farmland control soil | 0–10 | 6.57 ± 0.14 | 17.88 ± 0.17 | 146.38 ± 0.11 | 20.90 ± 1.98 | 87.22 ± 3.14 |

| 10–20 | 7.19 ± 0.03 | 12.61 ± 0.20 | 144.93 ± 0.06 | 19.23 ± 0.05 | 80.23 ± 3.28 | ||

| 20–30 | 7.12 ± 0.13 | 10.43 ± 0.09 | 105.95 ± 0.33 | 17.70 ± 1.14 | 90.16 ± 3.51 | ||

| 30–40 | 7.41 ± 0.11 | 9.28 ± 0.07 | 98.22 ± 0.12 | 11.88 ± 0.09 | 76.86 ± 0.01 | ||

| 3 | Fly ash−filled soil | 10.58 ± 0.06 | 18.10 ± 0.67 | 145.02 ± 2.34 | 58.95 ± 2.31 | 30.10 ± 4.90 |

| No. | Nutrient Index | Tartaric Acid | Oxalic Acid | Malonic Acid | Lactic Acid | Citric Acid | Ssuccinic Acid | Propionic Acid | Acetic Acid |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | pH | 0.124 | −0.802 ** | −0.889 ** | −0.218 | −0.423 * | −0.37 | −0.126 | −0.424 * |

| 2 | Available potassium | −0.508 * | −0.638 ** | −0.085 | 0.149 | 0.708 ** | 0.217 | 0.258 | −0.316 |

| 3 | Organic matter | −0.179 | 0.393 | 0.488 * | 0.648 ** | 0.510 * | 0.295 | 0.172 | 0.316 |

| 4 | Alkali−hydrolyzable nitrogen | −0.559 ** | 0.411 * | 0.607 ** | −0.111 | 0.397 | 0.176 | 0.001 | 0.371 |

| 5 | Available phosphorus | −0.115 | 0.679 ** | 0.710 ** | −0.049 | 0.453 * | −0.051 | −0.193 | 0.644 ** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zheng, Y.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, F.; Ma, Q.; Kong, Z.; Ma, Y. Distribution Characteristics of Low-Molecular-Weight Organic Acids in Reclaimed Soil Filled with Fly Ash: A Study. Toxics 2024, 12, 312. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics12050312

Zheng Y, Wu Y, Zhang Z, Chen F, Ma Q, Kong Z, Ma Y. Distribution Characteristics of Low-Molecular-Weight Organic Acids in Reclaimed Soil Filled with Fly Ash: A Study. Toxics. 2024; 12(5):312. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics12050312

Chicago/Turabian StyleZheng, Yonghong, Yue Wu, Zhiguo Zhang, Fangling Chen, Qingbin Ma, Zihao Kong, and Ying Ma. 2024. "Distribution Characteristics of Low-Molecular-Weight Organic Acids in Reclaimed Soil Filled with Fly Ash: A Study" Toxics 12, no. 5: 312. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics12050312

APA StyleZheng, Y., Wu, Y., Zhang, Z., Chen, F., Ma, Q., Kong, Z., & Ma, Y. (2024). Distribution Characteristics of Low-Molecular-Weight Organic Acids in Reclaimed Soil Filled with Fly Ash: A Study. Toxics, 12(5), 312. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics12050312