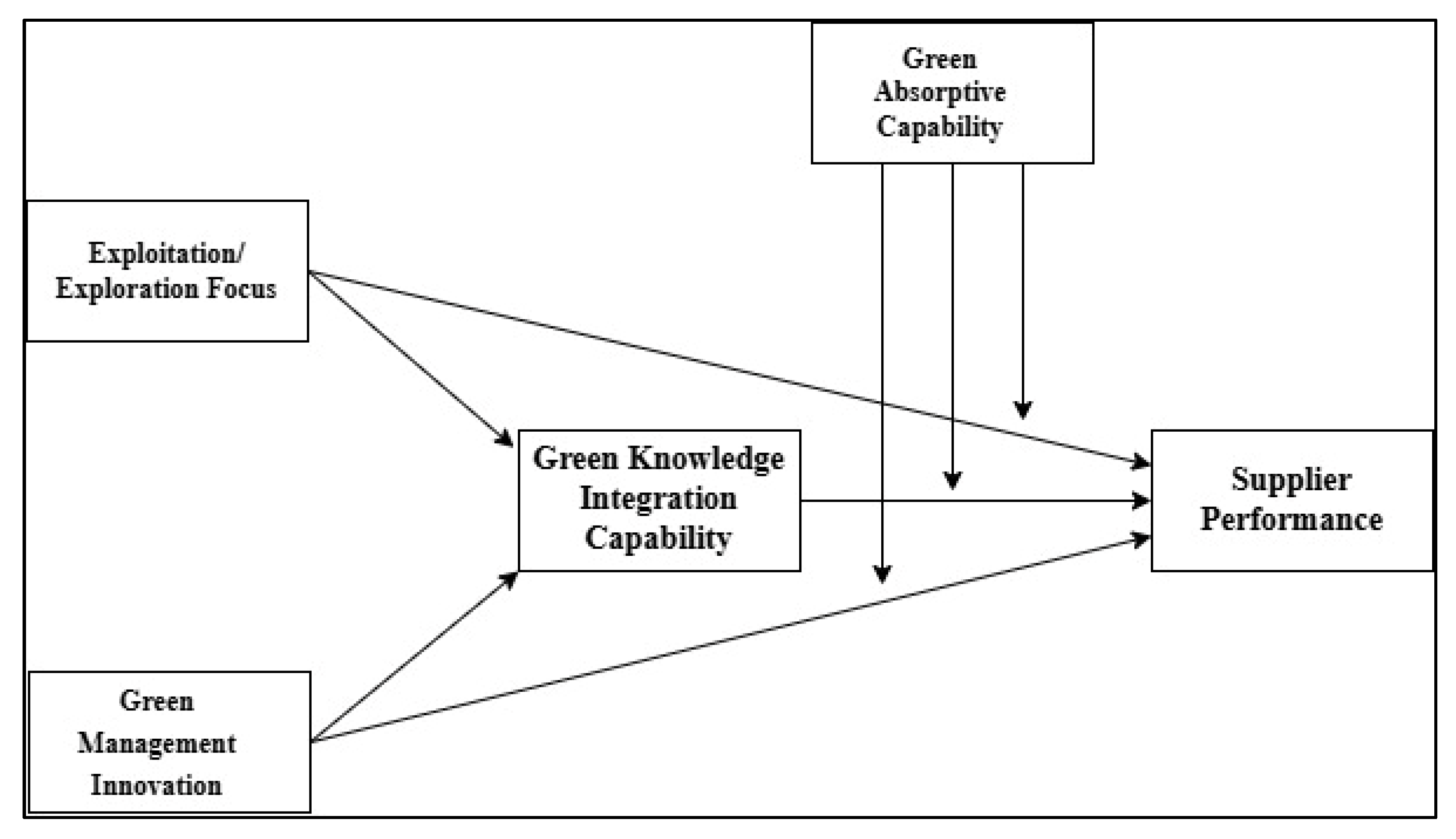

4.1. Hypothesis Testing

Table 5 reports on the direct relationship among the latent constructs. The results from the path analysis reveal significant and non-significant relationships between the predictors and supplier performance. EE focus indicates a significant and positive association with the supplier performance (β = 0.252,

p < 0.001), with a value of f-square of 0.164, which indicates a medium effect. The results infer that balancing between EE significantly improves the supplier’s performance. The empirical findings indicate that GMI has a positive yet insignificant effect on the supplier’s performance (β = 0.095,

p = 0.343, t = 0.948). The value of f-square is 0.33, which indicates that large effect size. Moreover, GKIC demonstrates a strong positive influence (β = 0.299,

p < 0.001, t = 5.542), suggesting that effective integration of green knowledge significantly boosts supplier outcomes. The value of f-square is 0.291, which indicates that large size effect. The results indicate that GKIC significantly and positively improves the supplier’s performance. Furthermore, GAC indicates an insignificant yet positive association with the supplier’s performance in the case of a direct relationship (β = 0.051,

p = 0.710). Despite the direct relationship, the indicated association is not statistically significant, with an f-square value of 0.201, indicating a medium effect size. The findings highlight that while knowledge integration and strategic focus are critical drivers, green management practices and absorptive capacity may require additional mediating or moderating factors to influence performance effectively.

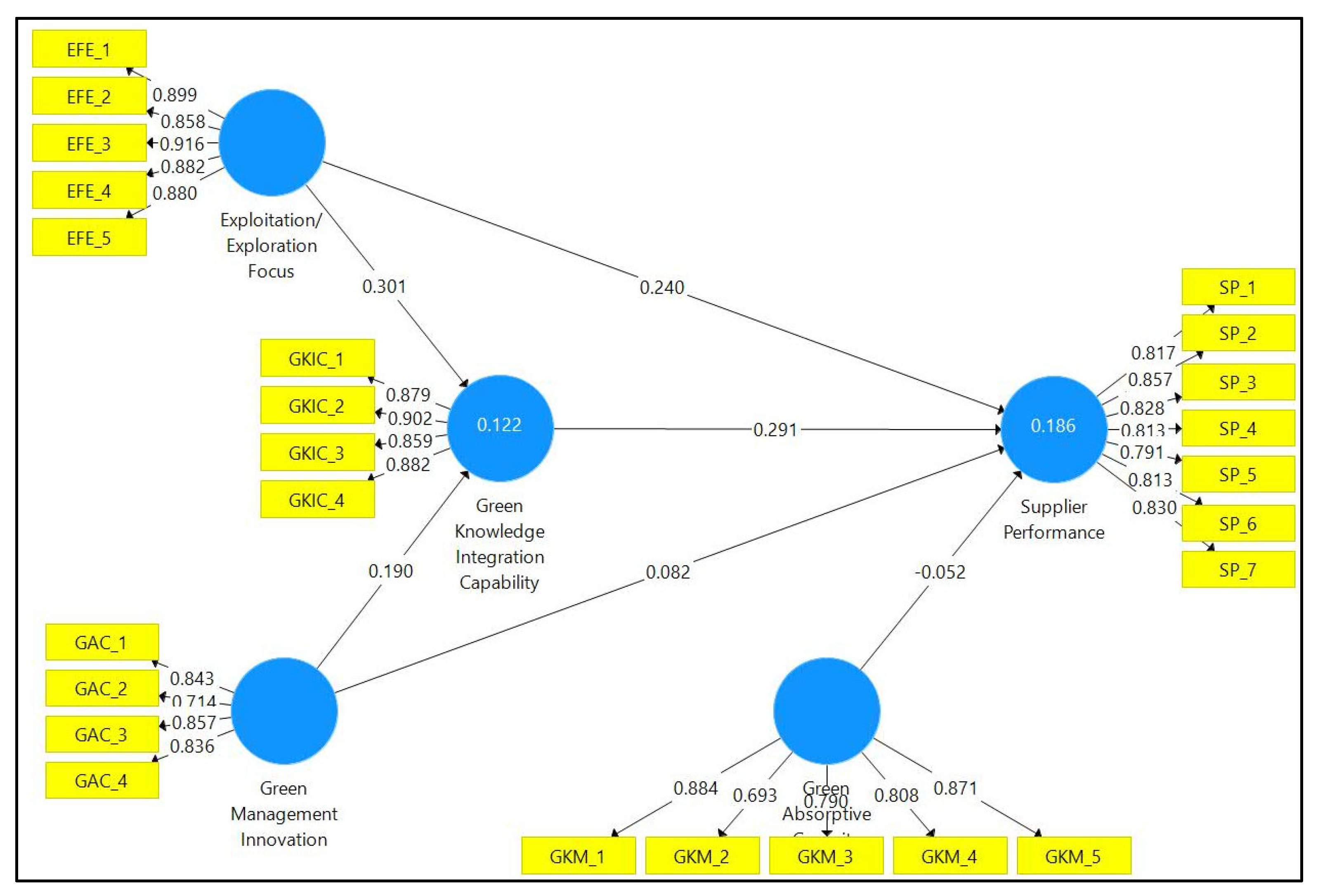

Table 6 reports the results of the indirect relationship between EE focus, GMI, and GKIC. The path analysis results indicate that both EE focus and GMI have a statistically significant positive influence on GKIC. The empirical findings indicate that balancing between EE activities more effectively predicts the GKIC (β = 0.301,

p < 0.001, t = 5.856). The f-square value is 0.103, which indicates a medium-sized effect. Moreover, GMI also shows a significant but comparatively weaker impact (β = 0.190,

p < 0.001, t = 3.787), implying that GMI practices contribute to, but are less decisive than, strategic EE focus in enhancing GKIC. However, the value of f-square is 0.141, indicating a medium-sized effect, which is comparatively higher than the EE focus. These findings underscore the significance of a dual strategic orientation (exploitation and exploration) as a primary driver of GKIC, with GMI serving a supportive yet secondary role. The empirical findings indicate that organisations aiming to improve the GKIC need to prioritise focusing on EE and GMI for optimal results.

Table 7 reports the mediation relationship of GKIC between EE focus, GMI, and SP. The empirical findings indicate that GKIC significantly and positively mediates the relationship between EE focus, GMI, and SP. The results indicate that GKIC significantly and positively mediates the relationship between EE focus and SP at a 1% level of significance (β = 0.090,

p < 0.001, t = 3.546). This indicates that a firm’s ability to balance EE enhances SP primarily by improving its capacity to GKIC. Furthermore, the empirical findings suggest that GKIC significantly and positively mediates the relationship between GMI and SP at a 1% level of significance (β = 0.057,

p = 0.003, t = 2.962), despite the direct relationship indicating that GMI positively yet insignificantly improves SP. This suggests that while GMI contributes to SP, its impact is partially channelled through improved GKIC. The results affirm that GKIC is considered a possible channel through which EE focuses and GMI improve SP.

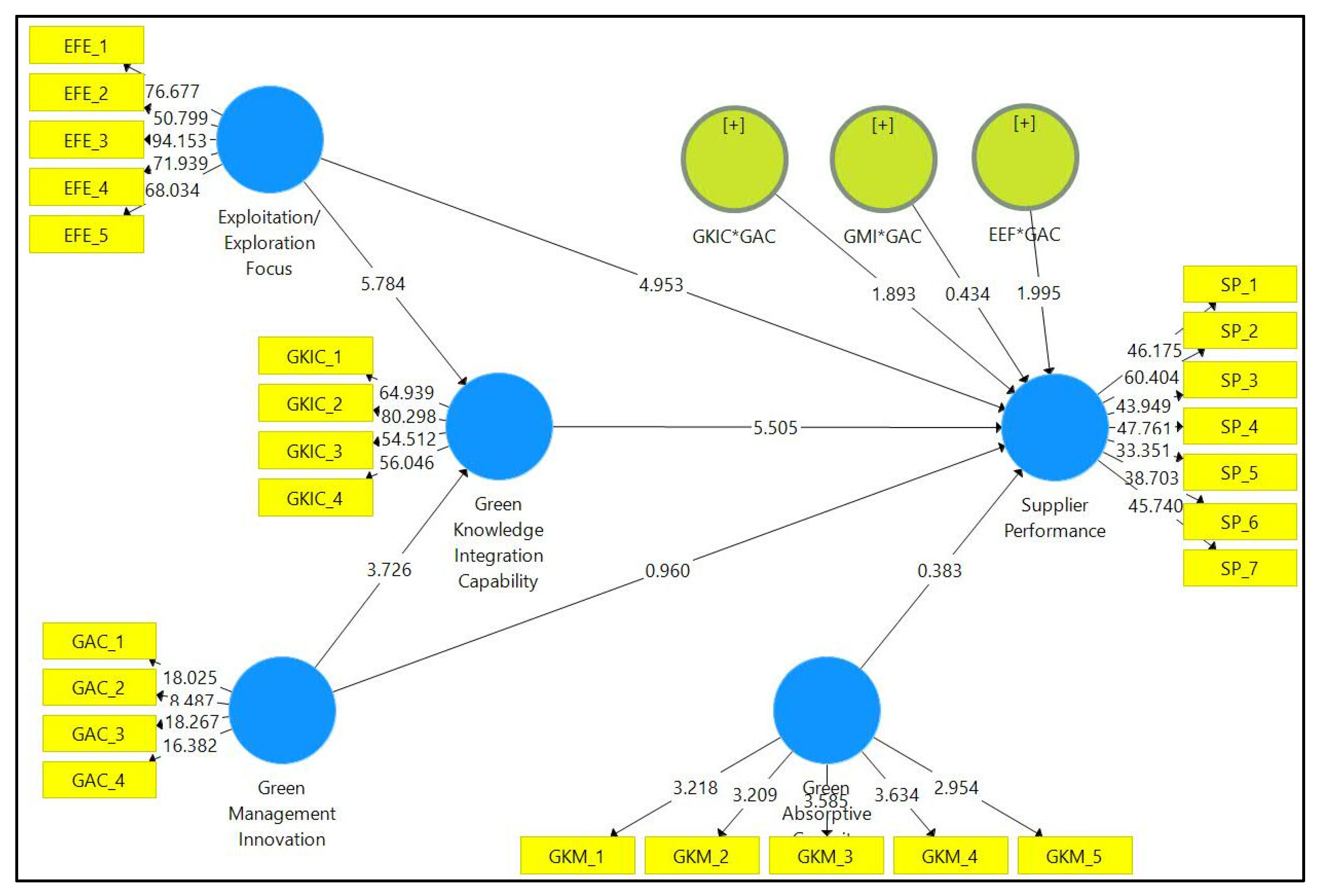

Table 8 and

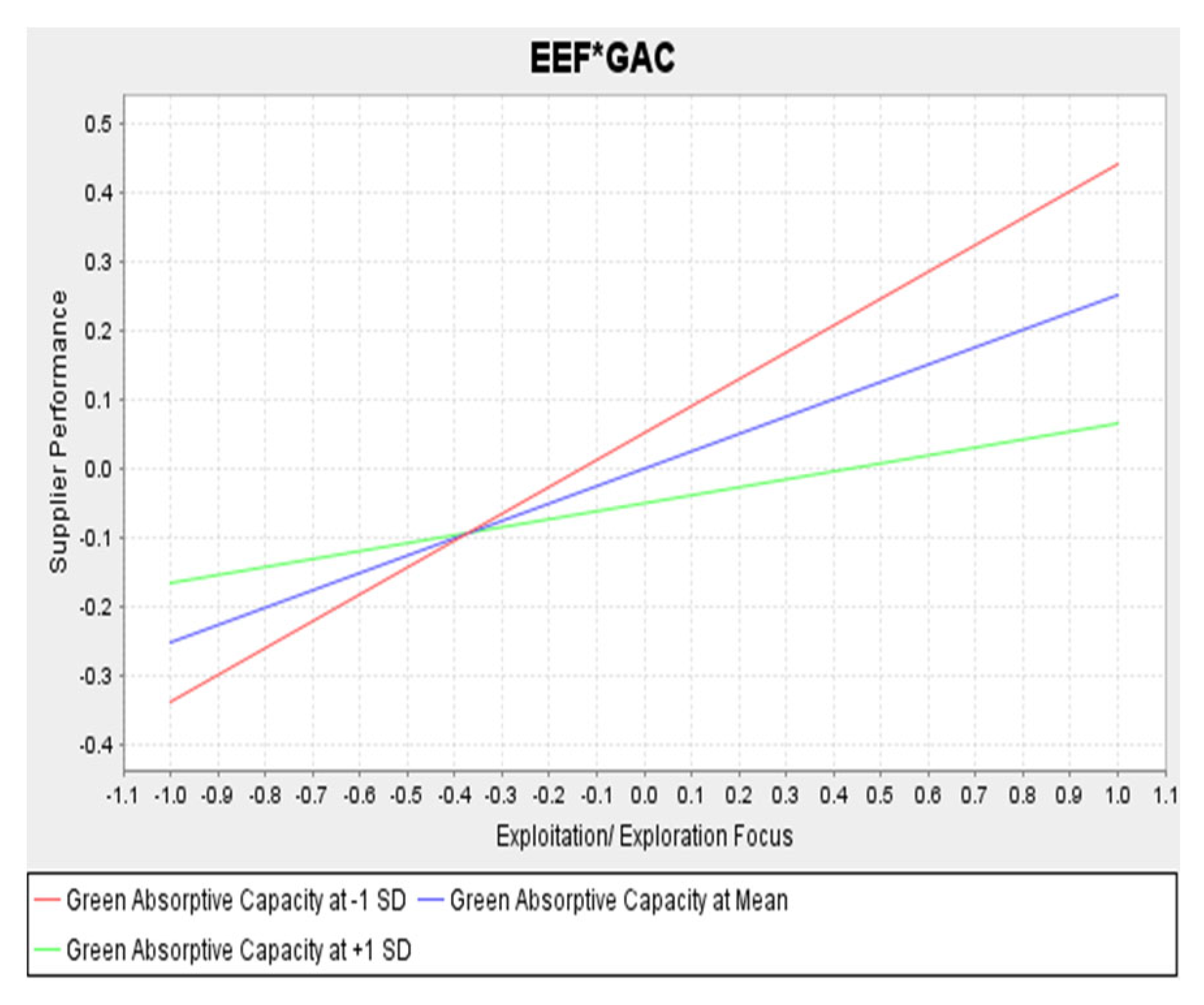

Figure 3 report the results of the moderation analysis. The present study proposed that GAC moderates the relationship between EE focus, GMI, GKIC, and SP. The interaction between EE focus and GAC [

Figure A1] has a positive and statistically significant effect on SP (β = 0.137,

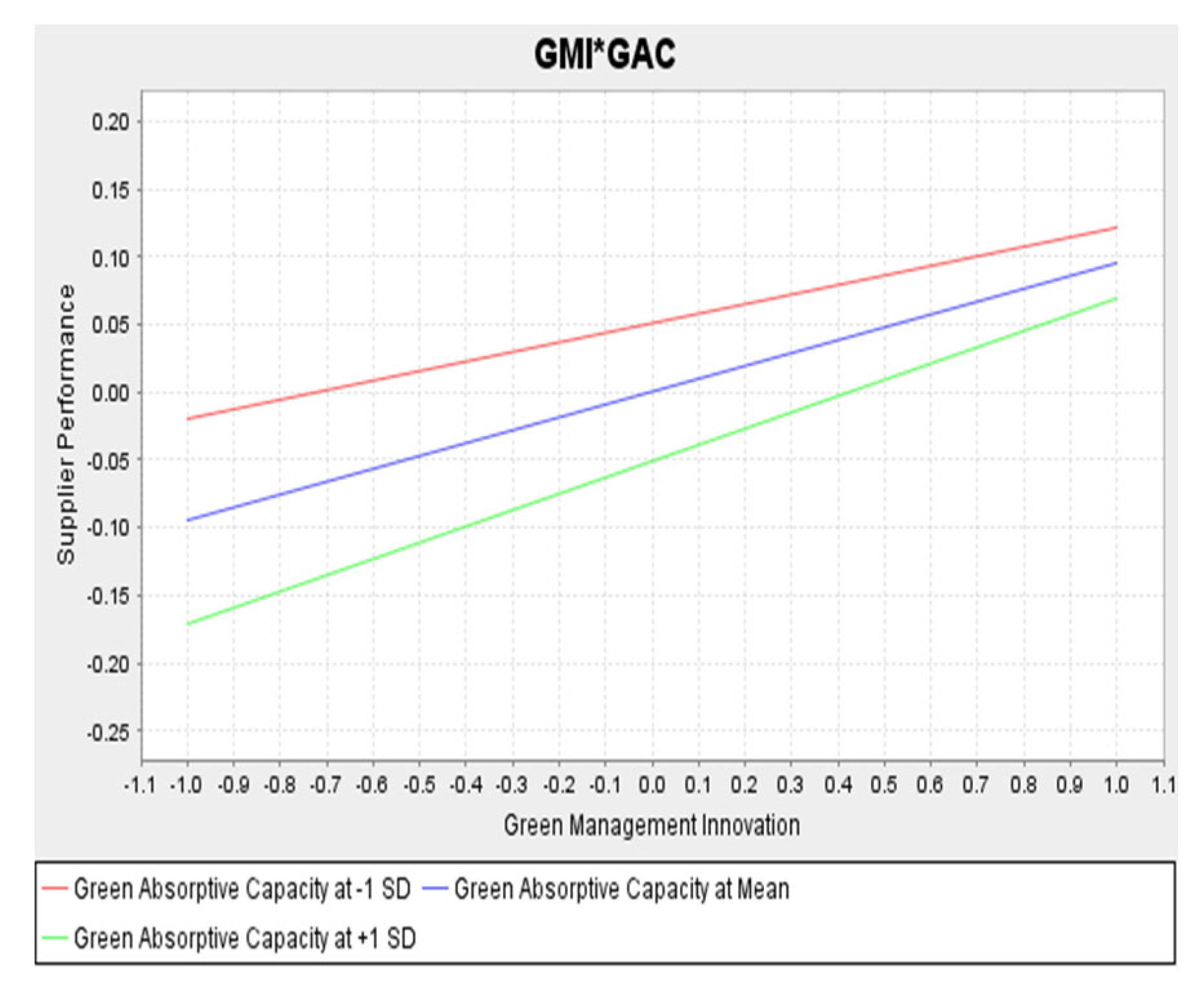

p = 0.050, t = 1.962), indicating that firms with higher GAC can more effectively leverage their strategic balancing of exploitation and exploration activities to enhance SP. The empirical findings affirm that GAC acts as an enabler in transforming strategic ambidexterity into superior supplier outcomes through improved knowledge assimilation and utilisation. Moreover, the empirical findings indicate that although GAC positively moderates the relationship between GMI and SP [

Figure A2] (β = 0.025,

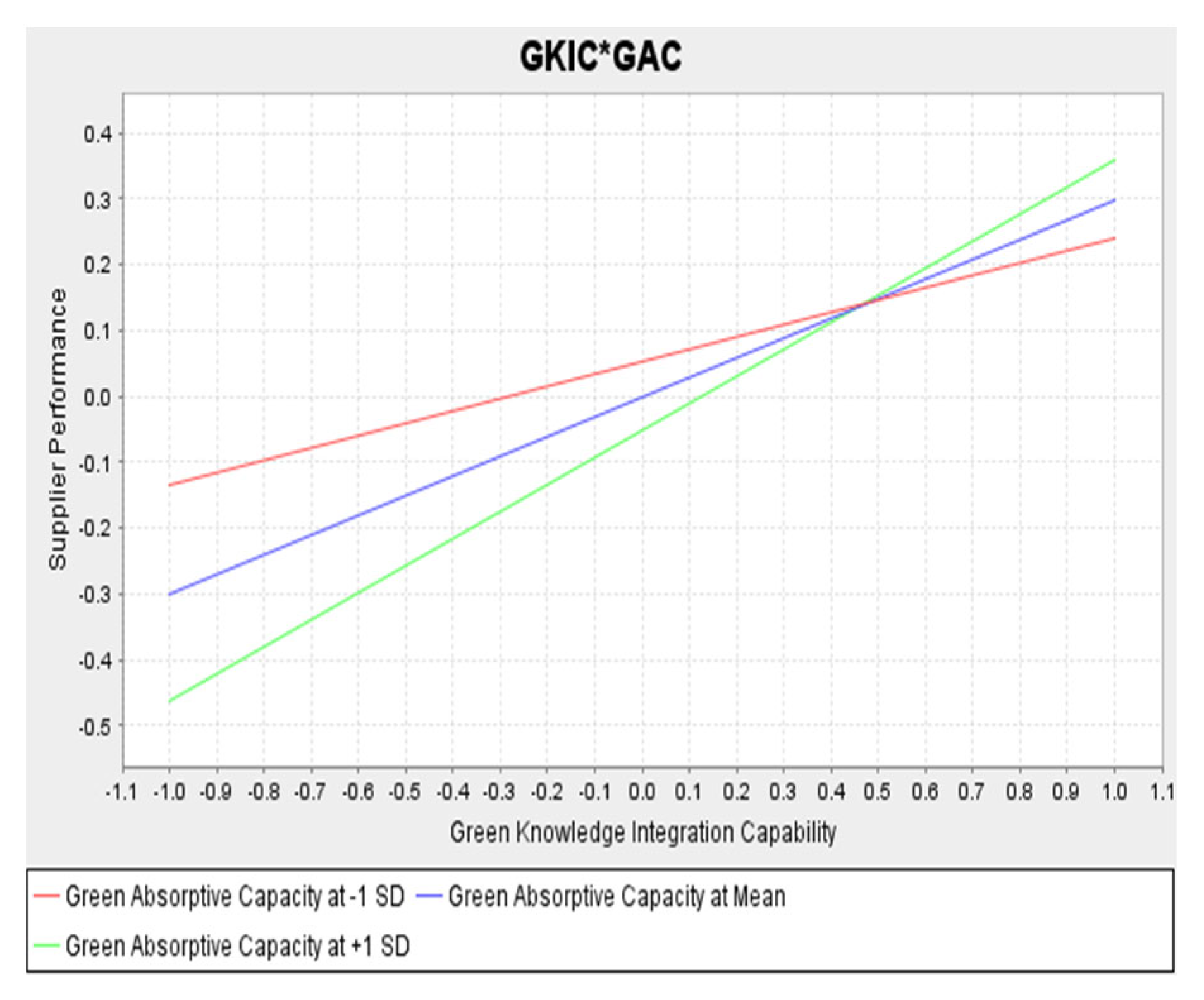

p = 0.670), this effect is statistically insignificant, implying that green managerial initiatives alone may not yield performance benefits unless they are supported by strong absorptive routines. Furthermore, the empirical findings show that the moderating effect of GAC on the relationship between GKIC and SP [

Figure A3] is positive yet statistically insignificant at conventional thresholds (β = 0.112,

p = 0.055), reflecting a marginal trend toward significance. These results collectively suggest that while GAC enhances the translation of strategic ambidexterity into supplier performance, its enabling influence on green innovation and knowledge integration pathways may require higher capability levels or additional contextual enablers to become fully effective and robust.

The selective moderation effect of GAC supports the argument that absorptive routines are path-dependent, meaning they evolve primarily from existing knowledge bases [

33,

48]. As EE focus emphasises refining current practices while exploring new solutions, firms with stronger GAC can more swiftly internalise and exploit environmental knowledge, translating ambidexterity into performance gains [

46]. However, GMI and GKIC may not benefit equally from GAC at all stages. Green innovations often require new routines, technologies, and partner alignment before their impact materialises, and thus their value realisation depends on longer-term organisational learning cycles [

20]. Likewise, GKIC already captures assimilation and integration mechanisms, making GAC’s additional contribution less distinctive unless firms have achieved higher maturity in knowledge transformation routines [

47]. Consequently, the moderating influence of GAC is more apparent where strategic ambidexterity leverages accumulated knowledge stocks, rather than in contexts where innovation or integration requires creating and codifying new environmental practices [

42]. These results highlight that GAC enhances performance most effectively when building on existing learning trajectories rather than initiating novel sustainability capabilities.

4.2. Findings and Discussion

The findings offer critical insights into the mechanisms through which EE focus, GMI, and GKIC influence SP, with GAC playing a contingent role. The present study contextualises the findings within the recent literature and, based on the discussion in the next section, outlines the theoretical and practical implications. The significant positive effect of EE focus on SP (β = 0.252,

p < 0.001) aligns with ambidexterity theory [

8,

31], which posits that balancing exploitation (refinement of existing knowledge) and exploration (pursuit of new knowledge) enhances organisational adaptability and performance. The empirical findings extend the existing literature in the domain of supply chain research, which affirms that ambidextrous balance strategies significantly improve the supplier outcome through dynamic capability [

5]. GMI’s insignificant direct effect on SP (β = 0.095,

p = 0.343) contrasts with studies linking green innovation to performance [

31,

41]. This discrepancy in empirical findings might reflect the contextual factors in Pakistani MNCs, where institutional voids or insufficient supplier capacity limit the immediate impact [

54,

63]. Recent work by Du and Wang (2022) [

53] suggests that GMI’s benefits often materialise indirectly through knowledge integration, which our mediation analysis supports.

In addition to that the mediation results indicate that GKIC’s pivotal role acts as a “knowledge bridge” between EE focus and SP (β = 0.090,

p < 0.001) as well as GMI and SP (β = 0.057,

p = 0.003) [

67]. This aligns with SET, as GKIC facilitates reciprocal knowledge sharing between MNCs and suppliers, fostering trust and long-term collaboration [

62]. The empirical findings indicate that stronger mediation for EE focus, as compared to GMI, suggests that ambidextrous strategies are more effective than standalone innovations in cultivating GKIC, balancing exploitation and exploration [

42].

The significant moderation of EE focus × GAC → SP (β = 0.137,

p = 0.050) supports GAC [

48]. Firms with high GAC better leverage ambidextrous strategies to drive SP, as they can assimilate and apply external green knowledge [

33]. The empirical results affirm that GAC significantly mitigates the tensions in sustainable supply chains [

10]. However, GAC insignificantly moderates the relationship between GMI (β = 0.025,

p = 0.670), GKIC (β = 0.112,

p = 0.055), and SP. GMI’s operational nature (e.g., eco-design, waste reduction) may not require extensive knowledge absorption, whereas GAC partially amplifies GKIC’s impact, consistent with Pacheco et al. (2018) [

21].

The empirical findings indicate that EE focus and GKIC significantly improve the SP, while the recent literature emphasises ambidexterity in sustainable supply chains [

42,

46]. The strong mediating effect of GKIC suggests that firms leveraging both existing and new knowledge more effectively integrate green practices, leading to improved supplier outcomes. The findings of the present study are well aligned with recent literature which affirms that knowledge integration is pivotal for competitive sustainability [

66,

71]. However, the empirical findings of the present study indicate that GMI had no direct impact on SP, contradicting but aligning with the fact that, often, SP depends on contextual factors such as GAC [

10].

The moderating role of GAC was significant only for the EE focus–SP link, suggesting that GAC amplifies the benefits of strategic ambidexterity, but not those of standalone GMI or GKIC. The earlier literature claims that GAC efficacy depends on the type of knowledge being absorbed by collaborative partners [

33]. The near-significant moderation for GKIC (

p = 0.055) hints at a potential threshold effect, where only high GAC levels may unlock GKIC’s full potential [

53].

These findings indicate that the performance value of GMI may be conditional, emerging only when firms possess strong knowledge integration routines. Similarly, GAC’s selective influence highlights a contextual boundary condition, where absorptive routines reinforce ambidextrous strategies more effectively than new green practices, especially in emerging markets with heterogeneous supplier capabilities.

The finding that GMI does not directly enhance supplier performance suggests that adopting green innovations alone may not be sufficient to deliver operational improvements without the presence of enabling knowledge capabilities. One explanation relates to implementation gaps, where eco-innovations are introduced but not fully embedded into supplier routines due to limited codification, training, or resource alignment [

45]. Additionally, supplier heterogeneity in emerging economies creates variation in technological readiness, meaning GMI outcomes rely heavily on suppliers’ ability to absorb and operationalize green practices [

46,

47]. Drawing on eco-innovation theory, GMI often prioritises environmental improvements that do not immediately translate into efficiency or performance gains unless complemented by strong learning systems [

20,

39]. Further, diffusion of innovation theory highlights that innovation benefits unfold gradually as knowledge diffuses across supply chain partners [

44]. Therefore, without robust GKIC mechanisms to assimilate, transform, and apply environmental knowledge, GMI may remain symbolic or compliance-driven rather than value-creating. This supports our empirical observation that GKIC transmits the performance value of GMI by enabling suppliers to translate innovation initiatives into tangible process improvements.