Development and Validation of a Real-Time PCR Based Assay to Detect Adulteration with Corn in Commercial Turmeric Powder Products

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant and Food Sample Preparation

2.1.1. Reference Binary Mixtures

2.1.2. Blind Samples

2.2. DNA Extraction

2.3. Sequence Analysis and Primer Design

2.4. Quantitative Real-Time PCR

2.5. Cloning of PCR Amplicons and Sequencing

2.6. Standard Curve Construction and Data Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Design of Species-Specific Primers

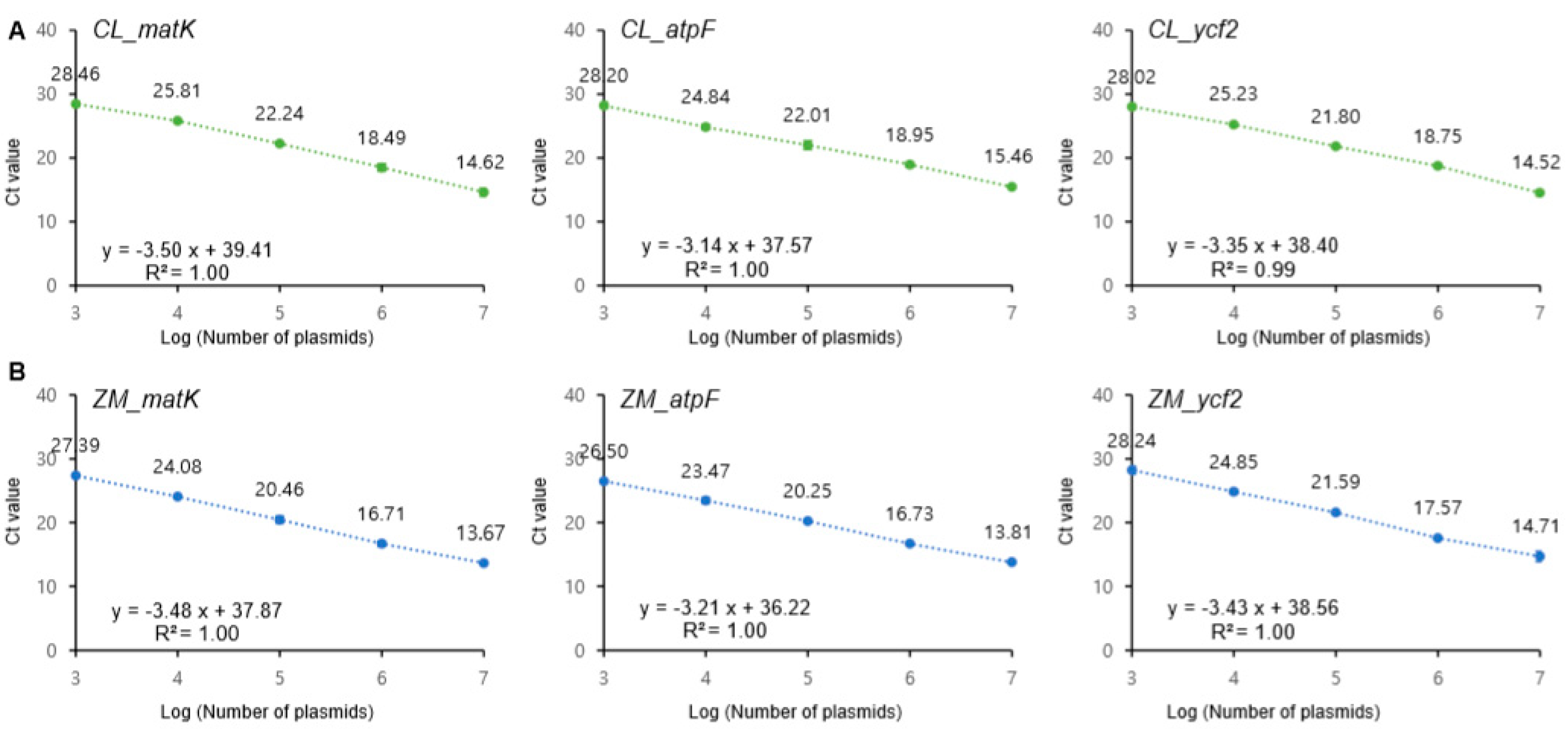

3.2. Amplification Efficiency of the Designed Primer Sets

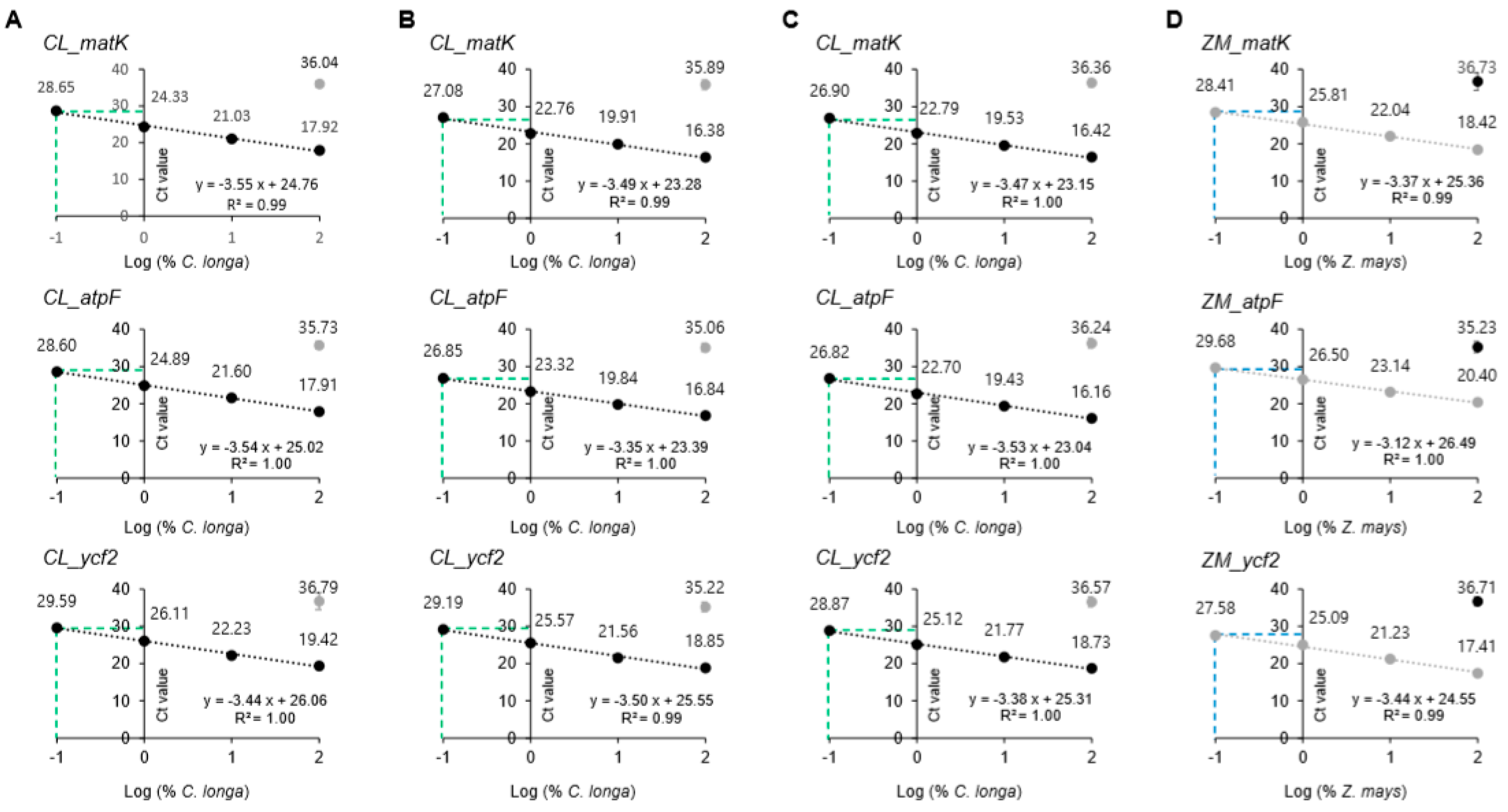

3.3. Sensitivity and Specificity of the Assay

3.4. Application of the Developed Real-Time PCR Assay to Blind Samples

3.5. Application of the Developed Assay in Commercial Products

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Priyadarsini, K.I. The chemistry of curcumin: From extraction to therapeutic agent. Molecules 2014, 19, 20091–20112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curcumin Market Size, Share & Trends Analysis Report by Application (Pharmaceutical, Food, Cosmetics), by Region (North America, Europe, Asia Pacific, Central & South America, Middle East & Africa), and Segment Forecasts, 2020–2027. Available online: https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/turmeric-extract-curcumin-market (accessed on 26 April 2020).

- Aggarwal, B.B.; Kumar, A.; Bharti, A.C. Anticancer potential of curcumin: Preclinical and clinical studies. Anticancer Res. 2003, 23, 363–398. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, S.C.; Patchva, S.; Aggarwal, B.B. Therapeutic Roles of Curcumin: Lessons Learned from Clinical Trials. AAPS J. 2013, 15, 195–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panahi, Y.; Hosseini, M.S.; Khalili, N.; Naimi, E.; Simental-Mendia, L.E.; Majeed, M.; Sahebkar, A. Effects of curcumin on serum cytokine concentrations in subjects with metabolic syndrome: A post-hoc analysis of a randomized controlled trial. Biomed Pharmacother. 2016, 82, 578–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuptniratsaikul, V.; Dajpratham, P.; Taechaarpornkul, W.; Buntragulpoontawee, M.; Lukkanapichonchut, P.; Chootip, C.; Saengsuwan, J.; Tantayakom, K.; Laongpech, S. Efficacy and safety of Curcuma domestica extracts compared with ibuprofen in patients with knee osteoarthritis: A multicenter study. Clin. Interv. Aging 2014, 9, 451–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazzolani, F.; Togni, S. Oral administration of a curcumin-phospholipid delivery system for the treatment of central serous chorioretinopathy: A 12-month follow-up study. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2013, 7, 939–945. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, T.; Kawa, K.; Eckl, V.; Morton, C.; Stredney, R. Herbal supplement sales in US increase 7.7% in 2016. HerbalGram 2017, 115, 56–65. [Google Scholar]

- Pina, P. The Rise of Functional Foods. Think with Google Website. April 2016. Available online: www.thinkwithgoogle.com/consumer-insights/2016-food-trends-google/ (accessed on 19 July 2017).

- Food Trends 2016. Available online: https://think.storage.googleapis.com/docs/FoodTrends-2016.pdf (accessed on 19 July 2017).

- Turmeric Jumps from the Spice Rack to the Coffee Cup at Peet’s. Forbes. Available online: www.forbes.com/sites/michelinemaynard/ (accessed on 3 July 2018).

- Balakrishnan, K.V. Postharvest technology and processing of turmeric. In Turmeric: The Genus Curcuma; Ravindran, P.V., Nirmal Babu, K., Sivaraman, K., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2007; Volume 45, pp. 193–256. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, R. Food Fraud and “Economically Motivated Adulteration” of Food and Food Ingredients, Report, January 10, 2014; Washington DC. Available online: https://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc276904/ (accessed on 27 May 2020).

- Hong, E.Y.; Lee, S.Y.; Jeong, J.Y.; Park, J.M.; Kim, B.H.; Kwon, K.S.; Chun, H.S. Modern analytical methods for the detection of food fraud and adulteration by food category. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2017, 97, 3877–3896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, D.E.; Hellberg, R.S. Identification of species in ground meat products sold on the US commercial market using DNA-based methods. Food Control 2016, 59, 158–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, J.; Moon, J.C.; Jang, C.S. Markers for distinguishing Orostachys species by SYBR Green-based real-time PCR and verification of their application in commercial O. japonica food products. Appl. Biol. Chem. 2018, 61, 499–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arya, M.; Shergill, I.S.; Williamson, M.; Gommersall, L.; Arya, N.; Patel, H.R. Basic principles of real-time quantitative PCR. Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn. 2005, 5, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Calleja, I.; González, I.; Fajardo, V.; Martín, I.; Hernández, P.; García, T.; Martin, R. Real-time TaqMan PCR for quantitative detection of cows’ milk in ewes’ milk mixtures. Int. Dairy J. 2007, 17, 729–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ergün, Ş.; Ahmet, K. Practical Molecular Detection Method of Beef and Pork in Meat and Meat Products by Intercalating Dye Based Duplex Real-Time Polimerase Chain Reaction. Int. J. Food Prop. 2016, 19, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, S.; Yasmeen, J. Development and validation of fast duplex real-time PCR assays based on SYBER Green florescence for detection of bovine and poultry origins in feedstuffs. Food Chem. 2015, 173, 660–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chase, M.W.; Cowan, R.S.; Hollingsworth, P.M.; van den Berg, C.; Madriñán, S.; Petersen, G.; Seberg, O.; Jorgsensen, T.; Cameron, K.M.; Carine, M.A.; et al. A proposal for a standardized protocol to barcode all land plants. Taxon 2007, 56, 295–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayan, K.; Tsou, C.H. DNA Barcoding in Plants: Taxonomy in a New Perspective. Curr. Sci. 2010, 99, 1530–1541. [Google Scholar]

- Daniell, H.; Lin, C.S.; Yu, M.; Chang, M.J. Chloroplast genomes: Diversity, evolution, and applications in genetic engineering. Genome Biol. 2016, 17, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garino, C.; De Paolis, A.; Coisson, J.D.; Bianchi, D.M.; Decastelli, L.; Arlorio, M. Sensitive and specific detection of pine nut (Pinus spp.) by real-time PCR in complex food products. Food Chem. 2016, 194, 980–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollingsworth, P.M.; Forrest, L.L.; Spouge, J.L.; Hajibabaei, M.; Ratnasingham, S.; van der Bank, M.; Chase, M.W.; Cowan, R.S.; Erickson, D.L.; CBOL Plant Working Group; et al. A DNA barcode for land plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 12794–12797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caroline, P.L.; Anne, C.E. Development and Evaluation of a Real-Time PCR Multiplex Assay for the Detection of Allergenic Peanut Using Chloroplast DNA Markers. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 8623–8629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasikumar, B.; Remya, R.; John Zachariah, T. PCR Based Detection of Adulteration in the Market Samples of Turmeric Powder. Food Biotechnol. 2004, 18, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustin, S.A.; Benes, V.; Garson, J.A.; Huggett, J.; Kubista, M.; Mueller, R.; Nolan, T.; Pfaffl, M.W.; Shipley, G.L.; Vandesompele, J.; et al. The MIQE guidelines: Minimum information for publication of quantitative real-time PCR experiments. Clin. Chem. 2009, 55, 611–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ENGL (European Network of GMO Laboratories). Definition of Minimum Performance Requirements for Analytical Methods of GMO Testing. Available online: http://gmo-crl.irc.ec.ecrl.jrc.ec.europa.eu/doc/MPR%20Report%20Application%2020_10_2015.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2015).

- Yuan, J.S.; Reed, A.; Chen, F.; Stewart, C.N. Statistical analysis of real-time PCR data. BMC Bioinform. 2006, 7, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo, Y.; Shaw, P. DNA-based techniques for authentication of processed food and food supplements. Food Chem. 2018, 240, 767–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allmann, M.; Candrian, U.; Höfelein, C.; Lüthy, J. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR): A possible alternative to immunochemical methods assuring safety and quality of food Detection of wheat contamination in non-wheat food products. Z. Lebensm. Unters. Forch. 1993, 196, 248–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Target Species | Target Gene | Primer | Length (bp) | Sequence (5′→3′) | Size (bp) | Tm (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All plants | 18s rRNA region | 18s rRNA_F | 25 | TCTGCCCTATCAACTTTCGATGGTA | 137 | 58 |

| 18s rRNA_R | 25 | AATTTGCGCGCCTGCTGCCTTCCTT | ||||

| Curcuma longa | matK | CL_matK_F | 19 | CAATCCTATATGGTTGAGA | 171 | 55 |

| CL_matK_R | 18 | GTCAGAAGACTCTATGGA | ||||

| atpF | CL_atpF_F | 20 | GCATTATTGGTTGATAGAGA | 194 | 58 | |

| CL_atpF_R | 22 | GTTTATTTCAAGAATAGGATGG | ||||

| ycf2 | CL_ycf2_F | 20 | GAAGAAGAGGAAGAGGACAT | 80 | 60 | |

| CL_ycf2_R | 20 | CATATTCTAGGAGCCCAAAC | ||||

| Zea mays | matK | ZM_matK_F | 19 | TTGATATCGAACATAATGC | 135 | 55 |

| ZM_matK_R | 16 | ACATCTTCTGGAACCT | ||||

| atpF | ZM_atpF_F | 19 | TGGAAGCAGATGAGTATCG | 160 | 60 | |

| ZM_atpF_R | 18 | TGTTGTCGGACCTGATTC | ||||

| ycf2 | ZM_ycf2_F | 20 | AAGAGGATGAGTTGTCAGAG | 99 | 59 | |

| ZM_ycf2_R | 18 | GCAAGAAGTCCGAATCAG |

| NO | Species | Plant Systems | Curcuma longa | Zea mays | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18s rRNA | CL_matK | Cl_atpF | CL_ycf2 | ZM_matK | ZM_atpF | ZM_ycf2 | |||

| 28 a (Cycles) | 28 (Cycles) | 29 (Cycles) | 28 (Cycles) | 29 (Cycles) | 28 (Cycles) | ||||

| 1 | Curcuma longa (Turmeric) | + | + b | + | + | - | - | - | |

| 2 | Hodeum vulgare (Barley) | + | - c | - | - | - | - | - | |

| 3 | Avena sativa (Oats) | + | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| 4 | Triticum aestivum (Wheat) | + | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| 5 | Zea mays (Corn) | + | - | - | - | + | + | + | |

| 6 | Oryza sativa (Rice) | + | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| 7 | Brassica oleracea var. capitate (Cabbage) | + | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| 8 | Ipomoea batatas (Sweat potato) | + | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| 9 | Arachis hypogaea (Peanuts) | + | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| 10 | Manihot esculenta (Cassava) | + | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| No. | Ingredient | PACa | Eb (%) | Z. mays Specific Primer Ct ± SD | A/D | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. longa (%) | Z. mays (%) | ZM_matK | ZM_atpF | ZM_ycf2 | ||||

| 1 | 99 | 1 | 13.57 ± 0.04 | 0.5–1.5 | 25.02 ± 0.06 | 25.61 ± 0.20 | 26.44 ± 0.21 | Ad |

| 2 | 98 | 2 | 14.73 ± 0.09 | 1–5 | 25.09 ± 0.02 | 24.78 ± 0.12 | 22.8 ± 0.18 | A |

| 3 | 100 | 0 | 14.03 ± 0.01 | NDc | 31.51 ± 0.15 | 31.32 ± 0.26 | 35.15 ± 0.05 | A |

| 4 | 98 | 2 | 14.31 ± 0.01 | 1–5 | 24.40 ± 0.01 | 24.75 ± 0.15 | 23.92 ± 0.09 | A |

| 5 | 95 | 5 | 14.05 ± 0.01 | 1–5 | 23.72 ± 0.09 | 24.34 ± 0.09 | 21.94 ± 0.22 | A |

| 6 | 97 | 3 | 14.11 ± 0.06 | 1–5 | 23.45 ± 0.05 | 24.90 ± 0.07 | 22.97 ± 0.25 | A |

| 7 | 99.5 | 0.5 | 14.21 ± 0.02 | 0.5–1.5 | 25.09 ± 0.05 | 26.95 ± 0.07 | 26.34 ± 0.15 | A |

| 8 | 98.5 | 1.5 | 14.12 ± 0.05 | 0.5–1.5 | 25.59 ± 0.03 | 26.32 ± 0.10 | 24.69 ± 0.19 | A |

| 9 | 100 | 0 | 14.33 ± 0.08 | ND | 31.67 ± 0.20 | 31.01 ± 0.80 | 34.89 ± 0.10 | A |

| 10 | 98.5 | 1.5 | 14.23 ± 0.03 | 0.3–2 | 25.13 ± 0.09 | 25.69 ± 0.10 | 24.21 ± 0.02 | A |

| 11 | 99.5 | 0.5 | 14.27 ± 0.01 | 0.1–1 | 26.06 ± 0.09 | 27.08 ± 0.10 | 26.19 ± 0.09 | A |

| 12 | 100 | 0 | 13.61 ± 0.12 | ND | 31.33 ± 0.28 | 30.98 ± 0.11 | 34.46 ± 0.26 | A |

| 13 | 97 | 3 | 14.31 ± 0.10 | 1–5 | 24.97 ± 0.09 | 24.37 ± 0.07 | 23.86 ± 0.13 | A |

| 14 | 98 | 2 | 13.22 ± 0.07 | 1–5 | 24.19 ± 0.09 | 26.14 ± 0.12 | 23.22 ± 0.09 | A |

| 15 | 96 | 4 | 13.33 ± 0.06 | 1–5 | 23.92 ± 0.15 | 24.26 ± 0.03 | 22.72 ± 0.27 | A |

| 16 | 99 | 1 | 14.26 ± 0.05 | 0.1–1 | 25.75 ± 0.10 | 26.75 ± 0.14 | 25.11 ± 0.10 | A |

| 17 | 93 | 7 | 13.95 ± 0.07 | 5–10 | 22.11 ± 0.11 | 23.99 ± 0.13 | 21.72 ± 0.11 | A |

| 18 | 90 | 10 | 13.74 ± 0.02 | 10–15 | 22.11 ± 0.10 | 21.99 ± 0.18 | 21.23 ± 0.13 | A |

| 19 | 100 | 0 | 16.21 ± 0.07 | ND | 30.82 ± 0.20 | 31.09 ± 0.01 | 34.06 ± 0.56 | A |

| 20 | 97 | 3 | 13.27 ± 0.1 | 1–5 | 23.96 ± 0.05 | 24.28 ± 0.10 | 23.22 ± 0.12 | A |

| Real Commercial Products Tested that Labeled as 100% Curcuma longa | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Number | Plant System (18s rRNA) | CL_matK | CL_atpF | CL_ycf2 | ZM_matK | ZM_atpF | ZM_ycf2 |

| 1 | 14.49 | 14.83 | 14.10 | 14.24 | NDa | 34.00 | ND |

| ±0.15 | ±0.13 | ±0.17 | ±0.14 | ±0.07 | |||

| 2 | 15.23 | 15.27 | 15.70 | 14.50 | 38.26 | 33.59 | ND |

| ±0.06 | ±0.18 | ±0.09 | ±0.08 | ±1.1 | ±2.01 | ||

| 3 | 19.82 | 22.62 | 22.65 | 20.16 | 36.28 | 32.32 | 34.79 |

| ±0.08 | ±0.27 | ±0.04 | ±0.06 | ±0.61 | ±0.54 | ±0.47 | |

| 4 | 15.25 | 15.95 | 16.33 | 15.25 | 33.60 | 30.05 | 34.35 |

| ±0.06 | ±0.07 | ±0.03 | ±0.14 | ±0.20 | ±0.07 | ±0.21 | |

| 5 | 14.01 | 15.29 | 15.46 | 15.29 | 31.53 | 31.41 | ND |

| ±0.05 | ±0.07 | ±0.01 | ±0.07 | ±0.54 | ±0.56 | ||

| 6 | 19.19 | 17.68 | 21.97 | 15.28 | 32.34 | 31.14 | ND |

| ±0.03 | ±0.12 | ±0.04 | ±0.04 | ±0.76 | ±0.14 | ||

| 7 | 16.44 | 16.10 | 16.39 | 14.90 | 34.89 | 34.57 | ND |

| ±0.18 | ±0.03 | ±0.03 | ±0.09 | ±0.35 | ±0.65 | ||

| 8 | 18.87 | 15.35 | 20.24 | 14.10 | 32.82 | 34.55 | ND |

| ±0.08 | ±0.02 | ±0.12 | ±0.02 | ±0.33 | ±0.95 | ||

| 9 | 15.31 | 14.63 | 15.15 | 13.26 | 31.05 | 34.00 | ND |

| ±0.09 | ±0.08 | ±0.06 | ±0.02 | ±4.55 | ±0.08 | ||

| 10 | 16.10 | 15.84 | 16.57 | 14.95 | 32.02 | 30.23 | 33.77 |

| ±0.01 | ±0.03 | ±0.02 | ±0.06 | ±0.24 | ±0.06 | ±0.92 | |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Oh, S.H.; Jang, C.S. Development and Validation of a Real-Time PCR Based Assay to Detect Adulteration with Corn in Commercial Turmeric Powder Products. Foods 2020, 9, 882. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods9070882

Oh SH, Jang CS. Development and Validation of a Real-Time PCR Based Assay to Detect Adulteration with Corn in Commercial Turmeric Powder Products. Foods. 2020; 9(7):882. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods9070882

Chicago/Turabian StyleOh, Su Hong, and Cheol Seong Jang. 2020. "Development and Validation of a Real-Time PCR Based Assay to Detect Adulteration with Corn in Commercial Turmeric Powder Products" Foods 9, no. 7: 882. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods9070882

APA StyleOh, S. H., & Jang, C. S. (2020). Development and Validation of a Real-Time PCR Based Assay to Detect Adulteration with Corn in Commercial Turmeric Powder Products. Foods, 9(7), 882. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods9070882