Use of Phytone Peptone to Optimize Growth and Cell Density of Lactobacillus reuteri

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Bacterial Strains and Inoculum Preparation

2.2. Protein Source

| Source | Description/Application | Suppliers |

|---|---|---|

| Peptone | Enzymatic digest of animal tissue, nitrogen in a form readily available to bacteria | Fisher Scientific |

| Tryptone | Pancreatic digest of casein is used as a nitrogen source for bacteria | Fisher Scientific |

| Proteose peptone #3 | Enzymatic digest of protein | BD Difco |

| Phytone peptone | Papaic digest of soybean meal, designed specifically for cell culture applications, non-animal origin | BD Difco |

| Tryptic soy broth | Dehydrated media for isolation, detection, and cultivation of a wide variety of microorganisms | BD Difco |

| Yeast extract | Water soluble portion of autolyzed yeast containing vitamin B complex, used in preparing microbiological culture media | Fisher Scientific |

| Beef extract | Desiccated beef powder used for culture media | BD Difco |

2.3. Preparation of Basal Medium (BM) for Protein Supplement

2.4. Bacterial Enumeration

2.5. Determination of pH Values

2.6. Determination of Buffering Capacity

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

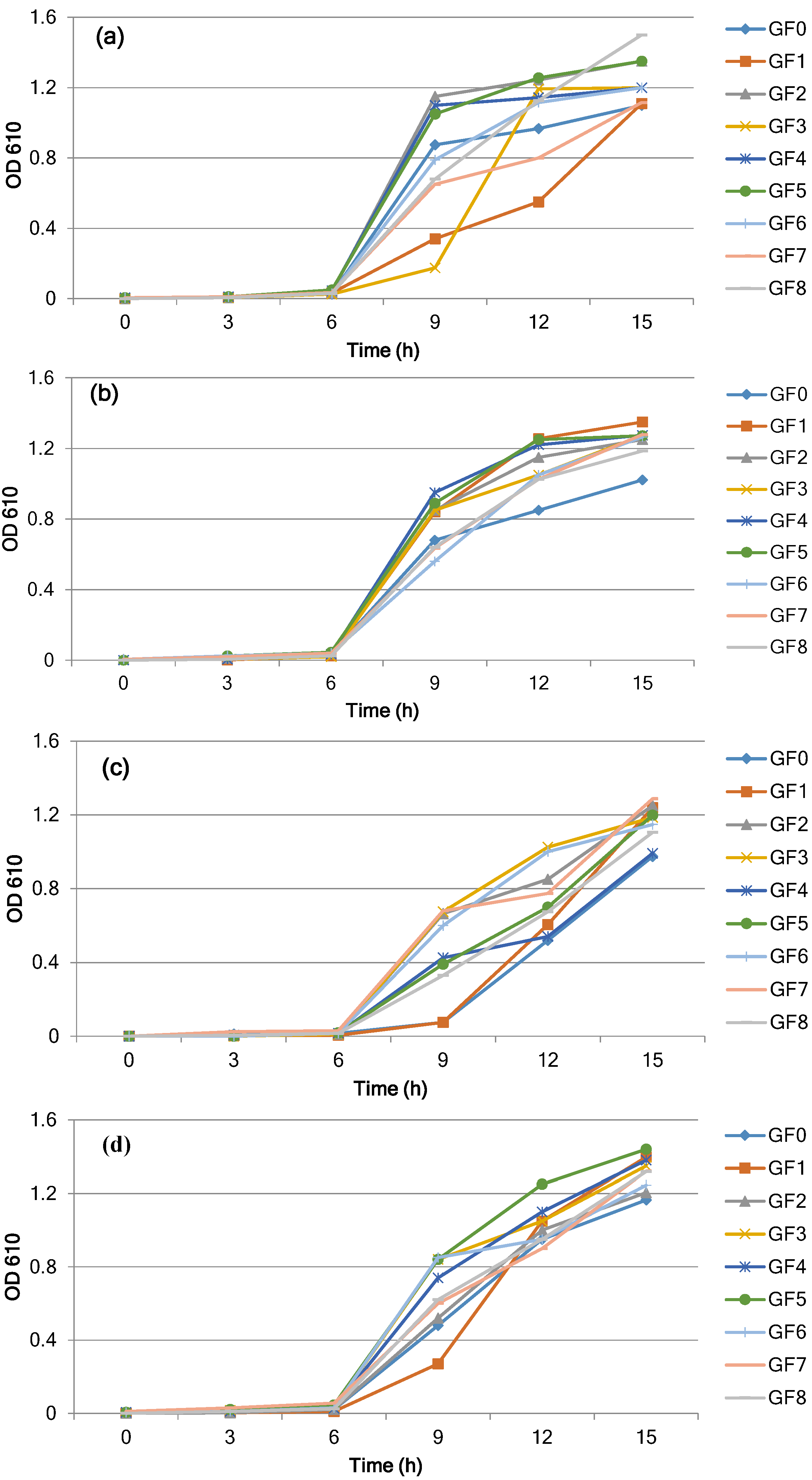

3.1. Growth and Cell Density of L. reuteri

| L.reuteri DSM 20016 | |||||||||

| Protein | GF0 | GF1 | GF2 | GF3 | GF4 | GF5 | GF6 | GF7 | GF8 |

| pH | 4.58 ± 0.17 | 4.69 ± 0.33 | 4.74 ± 0.22 | 4.78 ± 0.51 | 4.74 ± 0.32 | 4.69 ± 0.20 | 4.81 ± 0.12 | 4.74 ± 0.41 | 4.71 ± 0.33 |

| Log CFU/mL | 8.40 ± 0.31 | 8.59 ± 0.50 | 8.48 ± 0.14 | 9.59 ± 0.46* | 8.48 ± 0.18 | 10.05 ± 0.12* | 9.52 ± 0.21* | 8.48 ± 0.38 | 9.68 ± 0.29* |

| μmax a | 0.97 ± 0.19 | 0.55 ± 0.27 | 1.24 ± 0.33 | 1.19 ± 0.36 | 1.14 ± 0.19 | 1.26 ± 0.11 | 1.12 ± 0.30 | 0.80 ± 0.27 | 1.13 ± 0.14 |

| Buffer capacity | 8.39 ± 0.21 | 10.71 ± 0.33 | 10.31 ± 0.24 | 11.4 ± 0.31 | 10.31 ± 0.40 | 12.34 ± 0.10 | 11.86 ± 0.22 | 12.5 ± 0.23 | 10.31 ± 0.13 |

| L.reuteri SD 2112 | |||||||||

| Protein | GF0 | GF1 | GF2 | GF3 | GF4 | GF5 | GF6 | GF7 | GF8 |

| pH | 4.73 ± 0.54 | 4.78 ± 0.11 | 4.88 ± 0.45 | 4.91 ± 0.11 | 4.83 ± 0.22 | 4.74 ± 0.14 | 4.89 ± 0.15 | 4.87 ± 0.51 | 4.81 ± 0.32 |

| Log CFU/mL | 8.57 ± 0.39 | 9.52 ± 0.26* | 8.78 ± 0.12 | 9.72 ± 0.18* | 9.06 ± 0.17 | 9.86 ± 0.15* | 9.57 ± 0.34* | 8.53 ± 0.28 | 9.92 ± 0.25* |

| μmaxa | 0.85 ± 0.33 | 1.26 ± 0.33 | 1.15 ± 0.33 | 1.05 ± 0.13 | 1.22 ± 0.10 | 1.25 ± 0.13 | 1.05 ± 0.39 | 1.03 ± 0.17 | 1.03 ± 0.22 |

| Buffer capacity | 8.39 ± 0.49 | 10.71 ± 0.36 | 10.31 ± 0.42 | 11.4 ± 0.26 | 10.31 ± 0.27 | 12.34 ± 0.11 | 11.86 ± 0.18 | 12.5 ± 0.22 | 10.31 ± 0.49 |

| L. reuteri CF 2-7F | |||||||||

| Protein | GF0 | GF1 | GF2 | GF3 | GF4 | GF5 | GF6 | GF7 | GF8 |

| pH | 4.48 ± 0.32 | 4.54 ± 0.33 | 4.72 ± 0.45 | 4.66 ± 0.27 | 4.51 ± 0.17 | 4.51 ± 0.34 | 4.61 ± 0.17 | 4.59 ± 0.49 | 4.53 ± 0.27 |

| Log CFU/mL | 8.48 ± 0.15 | 9.79 ± 0.19* | 8.58 ± 0.31 | 9.64 ± 0.39* | 8.91 ± 0.23 | 9.91 ± 0.33* | 9.93 ± 0.19* | 8.59 ± 0.17 | 9.83 ± 0.19* |

| μmaxa | 0.52 ± 0.19 | 0.61 ± 0.33 | 0.85 ± 0.33 | 1.03 ± 0.32 | 0.54 ± 0.25 | 0.70 ± 0.12 | 1.00 ± 0.14 | 0.78 ± 0.35 | 0.68 ± 0.12 |

| Buffer capacity | 8.39 ± 0.28 | 10.71 ± 0.34 | 10.31 ± 0.36 | 11.40 ± 0.22 | 10.31 ± 0.17 | 12.34 ± 0.11 | 11.86 ± 0.39 | 12.5 ± 0.33 | 10.31 ± 0.19 |

| L. reuteri MF2-7F | |||||||||

| Protein | GF0 | GF1 | GF2 | GF3 | GF4 | GF5 | GF6 | GF7 | GF8 |

| pH | 5.05 ± 0.31 | 4.89 ± 0.48 | 4.78 ± 0.21 | 5.12 ± 0.36 | 5.30 ± 0.31 | 5.02 ± 0.11 | 5.05 ± 0.15 | 4.90 ± 0.22 | 5.13 ± 0.43 |

| Log CFU/mL | 8.40 ± 0.45 | 9.52 ± 0.52 | 8.51 ± 0.24 | 9.45 ± 0.10 | 9.68 ± 0.32* | 9.58 ± 0.23 | 9.54 ± 0.13 | 8.45 ± 0.15 | 9.40 ± 0.11 |

| μmaxa | 0.95 ± 0.36 | 1.05 ± 0.45 | 1.00 ± 0.19 | 1.05 ± 0.18 | 1.10 ± 0.17 | 1.25 ± 0.43 | 0.95 ± 0.12 | 0.90 ± 0.18 | 0.95 ± 0.39 |

| Buffer capacity | 8.39 ± 0.19 | 10.71 ± 0.38 | 10.31 ± 0.36 | 11.4 ± 0.24 | 10.31 ± 0.20 | 12.34 ± 0.31 | 11.86 ± 0.17 | 12.5 ± 0.29 | 10.31 ± 0.18 |

3.2. Changes in pH Values

3.3. Buffering Capacity of Selected Protein Sources on L. reuteri

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rosenfeldt, V.; Benfeldt, E.; Nielsen, S.D.; Michaelsen, K.F.; Jeppesen, D.L.; Valerius, N.H.; Paerregaard, A. Effect of probiotic lactobacillus strains in children with atopic dermatitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2003, 111, 389–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krasse, P.; Carlsson, B.; Dahl, C.; Paulsson, A.; Nilsson, A.; Sinkiewicz, G. Decreased gum bleeding and reduced gingivitis by the probiotic Lactobacillus reuteri. Swed. Dent. J. 2005, 30, 55–60. [Google Scholar]

- Savino, F.; Pelle, E.; Palumeri, E.; Oggero, R.; Miniero, R. Lactobacillus reuteri (American type culture collection strain 55730) versus simethicone in the treatment of infantile colic: A prospective randomized study. Pediatrics 2007, 119, e124–e130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, D.; Hayek, S.; Ibrahim, S. Recent Application of Probiotics in Food and Agricultural Science; Rigobelo, E.C., Ed.; Intech Open Access Publisher: Manhattan, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Xanthopoulos, V.; Litopoulou-Tzanetaki, E.; Tzanetakis, N. Characterization of lactobacillus isolates from infant faeces as dietary adjuncts. Food Microbiol. 2000, 17, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kok, J.; Venema, G. Genetics of proteinases of lactic acid bacteria. Biochimie 1988, 70, 475–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, S.A.; Daguri, M. Bulk starter media for mesophilic starter cultures: A review. Dairy Food Environ. Sanit. 1996, 16, 823–828. [Google Scholar]

- Fuller, R. Probiotics in man and animals. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 1998, 66, 365–378. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim, S.A.; Bezkorovainy, A. Growth-promoting factors for bifidobacterium longum. J. Food Sci. 1994, 59, 189–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyawali, R.; Ibrahim, S.A. Impact of plant derivatives on the growth of foodborne pathogens and the functionality of probiotics. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012, 95, 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunji, E.R.; Mierau, I.; Hagting, A.; Poolman, B.; Konings, W.N. The proteotytic systems of lactic acid bacteria. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 1996, 70, 187–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Niel, E.; Hahn-Hägerdal, B. Nutrient requirements of lactococci in defined growth media. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1999, 52, 617–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porubcan, R.S.; Sellars, R.L. Lactic Starter Culture Concentrates: In Microbial Technology, 2nd ed.; Peppler, H.J., Perlman, D., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1979; Volume 1, pp. 59–92. [Google Scholar]

- De Man, J.; Rogosa, D.; Sharpe, M.E. A medium for the cultivation of lactobacilli. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 1960, 23, 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Møretrø, T.; Hagen, B.; Axelsson, L. A new, completely defined medium for meat lactobacilli. J. Appl. Microbial. 1998, 85, 715–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avonts, L.; van Uytven, E.; de Vuyst, L. Cell growth and bacteriocin production of probiotic lactobacillus strains in different media. Int. Dairy J. 2004, 14, 947–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalán, Z.; Hudáček, J.; Štětina, J.; Chumchalová, J.; Halász, A. Production of organic acids by lactobacillus strains in three different media. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2010, 230, 395–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayek, S.A.; Shahbazi, A.; Awaisheh, S.S.; Shah, N.P.; Ibrahim, S.A. Sweet potatoes as a basic component in developing a medium for the cultivation of lactobacilli. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2013, 77, 2248–2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Slyke, D.D. On the measurement of buffer values and on the relationship of buffer value to the dis-sociation constant of the buffer and the concentration and reaction of the buffer solution. J. Biol. Chem. 1922, 52, 525–570. [Google Scholar]

- Alazzeh, A.; Ibrahim, S.; Song, D.; Shahbazi, A.; AbuGhazaleh, A. Carbohydrate and protein sources influence the induction of α-and β-galactosidases in Lactobacillus reuteri. Food Chem. 2009, 117, 654–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drake, M.; Chen, X.; Tamarapu, S.; Leenanon, B. Soy protein fortification affects sensory, chemical, and microbiological properties of dairy yogurts. J. Food Sci. 2000, 65, 1244–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nancib, A.; Nancib, N.; Meziane-Cherif, D.; Boubendir, A.; Fick, M.; Boudrant, J. Joint effect of nitrogen sources and B vitamin supplementation of date juice on lactic acid production by Lactobacillus casei subsp. Rhamnosus. Bioresour. Technol. 2005, 96, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, S.; Lee, P.C.; Lee, E.G.; Chang, Y.K.; Chang, N. Production of lactic acid by Lactobacillus rhamnosus with vitamin-supplemented soybean hydrolysate. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 2000, 26, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudreau, H.; Champagne, C.; Jelen, P. The use of crude cellular extracts of Lactobacillus delbrueckii ssp. Bulgaricus 11842 to stimulate growth of a probiotic Lactobacillus rhamnosus culture in milk. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 2005, 36, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Atilola, O.A.; Gyawali, R.; Aljaloud, S.O.; Ibrahim, S.A. Use of Phytone Peptone to Optimize Growth and Cell Density of Lactobacillus reuteri. Foods 2015, 4, 318-327. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods4030318

Atilola OA, Gyawali R, Aljaloud SO, Ibrahim SA. Use of Phytone Peptone to Optimize Growth and Cell Density of Lactobacillus reuteri. Foods. 2015; 4(3):318-327. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods4030318

Chicago/Turabian StyleAtilola, Olabiyi A., Rabin Gyawali, Sulaiman O. Aljaloud, and Salam A. Ibrahim. 2015. "Use of Phytone Peptone to Optimize Growth and Cell Density of Lactobacillus reuteri" Foods 4, no. 3: 318-327. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods4030318

APA StyleAtilola, O. A., Gyawali, R., Aljaloud, S. O., & Ibrahim, S. A. (2015). Use of Phytone Peptone to Optimize Growth and Cell Density of Lactobacillus reuteri. Foods, 4(3), 318-327. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods4030318