The Slovenian Nutrition Guidelines 2025: A Comparison with the Prior Slovenian FBDG, Dietary Intake, and the EAT–Lancet Diet

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Data Sources and Comparison Framework (SNG2025; EAT–Lancet Diet; Previous Slovenian FBDGs; and Si. Menu 2017/18)

2.2. Harmonisation Rules

Standardisation and Units in SNG2025

2.3. Analytical Procedures

2.3.1. Food Group Mapping and Adherence Classification (Table 2)

2.3.2. External Corroboration

2.3.3. Comparability Constraints

2.3.4. Terminology

2.3.5. Comparative Specificity in SNG2025 (Bioavailability and Supplementation Guidance) Was Not Used as an Adjustment Factor

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative Comparison: The SNG2025 vs. EAT–Lancet Diet vs. Previous Slovenian FBDGs (Table 1)

3.2. Alignment of Slovenian Intakes with SNG2025 (Table 2)

3.2.1. Adherence to Recommended Intakes

3.2.2. Inadequate Intake

3.2.3. Excessive Intake

3.2.4. Non-Consumers

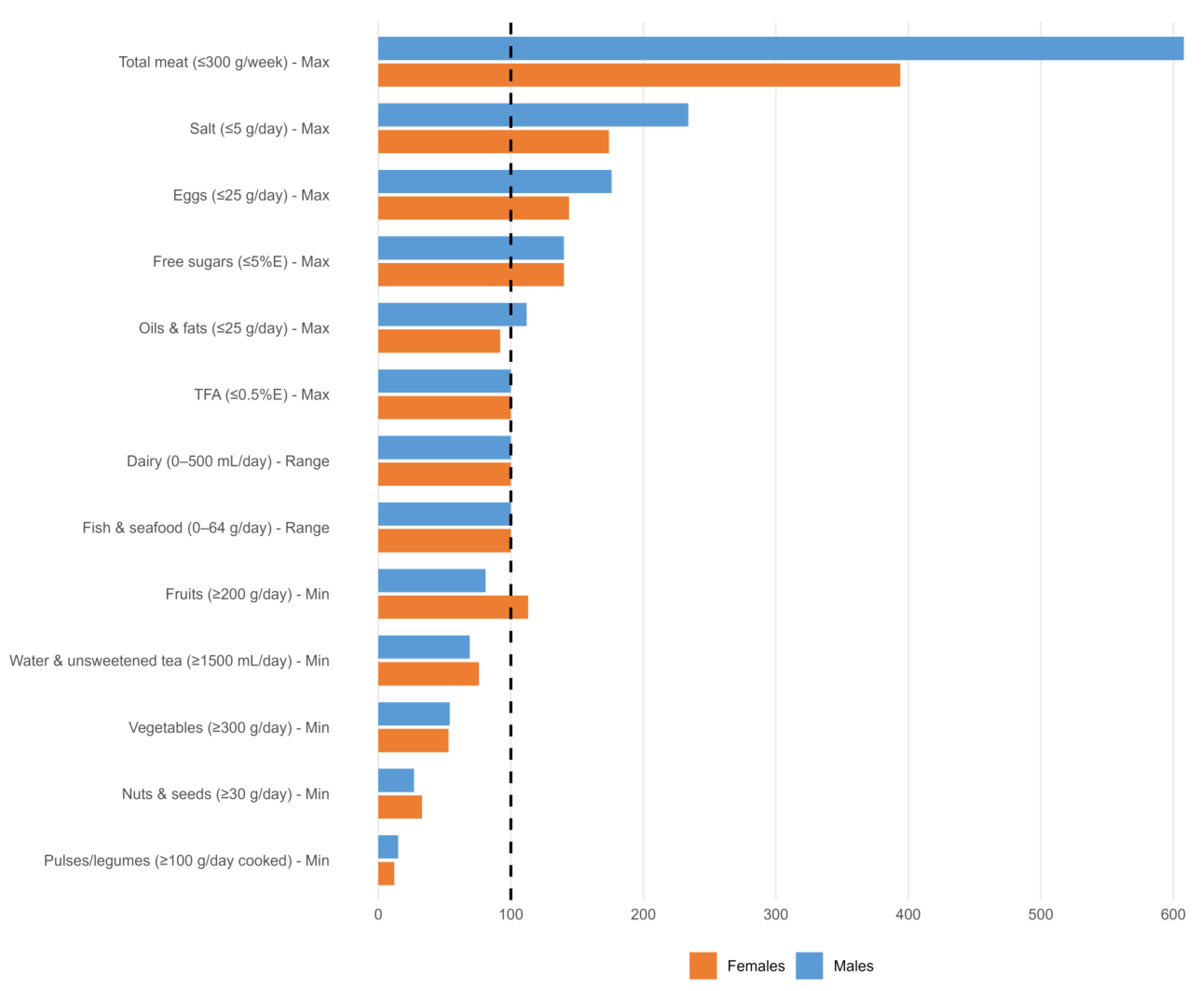

3.2.5. Sex-Specific Perspective

3.2.6. Comparisons Constrained by Data Availability

| Food Group | SNG2025 Daily Intake Guidance (g/Day Unless Noted) a per 2500 kcal | EAT–Lancet Reference Intake (Possible Range), (g/Day Unless Noted) a per 2500 kcal | Previous Slovenian FBDG Daily Intake Guidance (g/Day Unless Noted) kcal Not Specified | Slovenian Dietary Intakes Mean (g/day, Unless Indicated Otherwise) Males/Females (18–64 Years) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cereals/grains | ≥230 g dry (≈600 g cooked grains), (≥50% whole-grain products, <50% refined grains) | 232 g (125–232 g) | Not specified | Whole grains and whole-grain products: no data k Bread and bakery products: 210 g/145 g Breakfast cereals: 34 g/39 g Pasta, rice: 63 g/55 g |

| Potatoes and other starchy tubers | ≤200 g cooked, boiled/baked; not deep-fried. Avoid butter/lard/margarine; add only small amounts of oil; use iodised salt sparingly. | 50 g (0–100 g) | Not specified | Potatoes: 99 g/76 g |

| Vegetables | ≥300 g | 300 g (200–600 g) dark green ≈ 100 g red/orange ≈ 100 g other ≈ 100 g | 250–400 g green, white, orange yellow, red, and blue violet | Total:163 g/158 g Fresh:122 g/125 g Preserved and canned: 39 g/30 g |

| Fruits | 200 g (100–300 g) | 200 g (100–300 g) | 150–250 g | Total: 162 g/226 g Fresh: 141 g/198 g Canned, dry: 20 g/22 g |

| Pulses/legumes (dry beans, lentils, and peas) Soy foods (tofu/tempeh etc.) | ≥50 g dry legumes (≈100 g cooked legumes) + ≥25 g dry soy foods (≈70 g cooked soybeans or tofu/tempeh (as soy equivalents)) | 50 g (0–100 g) dry beans, lentils, and peas + 25 g (0–50 g) soy foods | Encouraged as meat substitutes; no gram target specified | Legumes and legume products: 14.6 g/11.6 g cooked Soy foods: no data k |

| Dairy or fortified plant-based alternatives b (1 MCE/day) c | 250 (0–500) mL milk/dairy (“as milk”) or calcium-fortified, plant-based drink/yoghurt b,c | 250 (0–500) dairy (milk or equivalent, e.g., cheese) | 400–600 mL/day of part skim or low-fat milk or yoghurt: or ≈ 120–180 g soft cheese ≈ 60–90 g hard cheese | Milk: 80 g/84 g Yoghurt and cream: 72 g/95 g Cheese: 35 g/32 g “As milk”: 292 mL/292 mL c1 |

| Meat and processed meat d | Total: 43 g/day, ≈≤300 g/week; (day-to-day 0–86 g/day; not 86 g × 7) d Prioritise poultry, reduce red and processed meat | 29 g (0–58): poultry 7 g (0–14): beef and lamb 7 g (0–14): pork 0 (aim for none): processed meat Total: ≤300 g/week | No gram target specified. 1–3×/week: poultry (lean cuts, skin removed) ≤1×/week: red meat (beef, pork, lamb, and game; limited/occasional only; lean cuts, remove visible fat) 1–2 meat-free days/week, replace fatty meats/products with legumes, fish, poultry or lean meat, choose lean cuts and avoid processed meats | Poultry: 72 g/65 g Red meat: 137 g/76 g Red meat and poultry: 209 g/141 g Processed meat: 52 g/28 g Total: 261 g/169 g Total: 1825 g/week/1183 g/week |

| Fish and seafood | 200 g/week (0–450 g) ≈29 g/day (0–64 g) | 28 g (0–100 g) | No gram target specified. 1–2×/week (include fatty marine fish; baked/steamed, not fried) | Fish and fish products: 27 g/18 g |

| Eggs | ≤25 g/day ≈3 eggs/week | 13 g (0–25 g) ≈1–3 eggs/week | Not specified | Eggs, including from foods: 44 g/36 g |

| Nuts and seeds | ≥30 g/day | 50 g (25–75 g) 25 g (0–75) peanuts 25 g tree nuts | Not specified | Fresh and processed nuts and seeds: 8 g/10 g |

| Oils and fats from whole foods (target: ≤25 g/day in addition to nuts and seeds) e | ≤25 g fat/oil; or ≤100 g avocado (20 g oil) + 8–10 olives (5 g oil) d limit/avoid: lard/tallow, butter, cream, and tropical fat | Added fats: a,f 40 g unsaturated plant oils/day (20–80) 6.8 (0–6.8): palm oil 5 (0–5): lard/tallow 0: dairy fat (included within dairy) | Upper limits were not specified for olive, rapeseed/canola, sunflower, soybean, and corn oils limit/avoid: lard/tallow, palm/coconut fat, butter, cream; fatty/processed meats/cheeses | Total: 28 g/23 g Vegetable oils and margarines: 20 g/16 g Butter and other animal fats: 8 g/7 g |

| Herbs and spices | Use regularly to minimise salt/sugar intake | Not specified | Use fresh, dried, or frozen herbs and spices instead of salt | No data k |

| Water and non-alcoholic beverages | ≈1500 mL (mineral) water, unsweetened tea as the default, Coffee permitted (≤400 mg caffeine/day) Fruit juice occasionally, ≤200 mL/day Avoid SSBs, especially energy drinks | Not quantified; water as the default | ≈1500–3000 mL (mineral) water), unsweetened fruit/herbal teas as the default fresh fruit/vegetable juices may be diluted 1:1 with water (consumed with meals) | Water: 925 mL/970 mL Tea: 106 mL/172 mL Coffee: 91 mL/104 mL Fruit/vegetable juices: 79 mL/46 mL SSBs: 136 mL/63 mL Cocoa and hot chocolate drink: 46 mL/46 mL |

| Alcohol | 0 mL | No numeric recommendation | M ≤20 g alcohol/day (≤14 units/week; ≤5 units/occasion) F ≤10 g alcohol/day (≤7 units/week; ≤3 units/occasion). 1 unit = 10 g alcohol ≈100 mL wine, 250 mL beer, or 30 mL spirits | Alcoholic beverages (mL/day) Wine: 33/18 Beer: 183/44 Spirits: 17/4 |

| Ultra-processed foods (UPFs) f | Avoid or minimise (limits in the salt, sugars, and fat rows) | Not quantified; keep low; see sugar/fat limits | Avoid or minimise | High-sugar foods (sugar, confectionery, cakes, cookies, and desserts): 98 g/107 g High salt and fat foods: no data k |

| Overall diet orientation i,j | <10% E from SFAs; <5% E from added/free sugars g <0.5% E TFAs; <5 g/day salt h | ≤31 g/day (0–31 g) added/free sugars g | Not specified. 5–10% E from added sugars avoid TFAs ≤5 g/day salt g | % E from SFAs: no data k 7%/7% E from free sugars 0.4–0.5% E from TFAs 11.7 g/8.7 g salt i |

| Food Group | SNG2025 (Mean of 3 Plates) Daily Intake Guidance (g/Day Unless Noted) per 2500 kcal a | Slovenian Dietary Intakes Mean (g/Day, Unless Indicated Otherwise) Males/Females (18–64 Years) | Below/Within/Above % of Target Males/Females |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cereals/grains | ≥230 g dry (≈600 g cooked), quality: ≥50% whole grains | No indicator for whole-grain vs. refined products | Whole-grain quality missing: Not computable |

| Potatoes and other starchy tubers | ≤200 g cooked ≤200 g cooked, boiled/baked; not deep-fried. Avoid butter/lard/margarine; add only small amounts of oil; use iodised salt sparingly. | Potatoes: 99 g/76 g (no data for other starchy tubers) | Within/Within 50%/38% of limit (≤200 g cooked/day) |

| Vegetables | ≥300 g | Total: 163 g/158 g | Below/Below 54%/53% |

| Fruits | 200 g (100–300 g) | Total:162 g/226 g | Below/Within 81%/113% |

| Pulses/legumes (dry beans, lentils, and peas) Soy foods (tofu/tempeh, etc.) | ≥50 g of dry legumes (≈100 g of cooked legumes) + ≥25 g of dry soy foods (≈70 g of cooked soybeans or tofu/tempeh (as soy equivalents)) | Legumes and legume products: 14.6 g/11.6 g cooked Soy foods: No data | Below/Below 15%/12% Soy foods: Not computable |

| Dairy or fortified plant-based alternatives b 1 MCE (~300 mg Ca)/day d | 250 (0–500) mL “as milk” or yoghurt/day = 250 (0–500) mL of fortified, plant-based drink/yoghurt; or ≈50–75 g of soft cheese or ≈27–42 g of hard cheese | Milk: 80/84 g Yoghurt and cream: 73 g/96 g Cheese: 35 g/32 g No separate data 292/292 mL “as milk” c1 | Within/Within 100%/100% (117%/117% vs. 250 mL/day midpoint) |

| Meat and processed meat | Total: 43 g/day (0–86 g) ≤300 g/week Prioritise poultry, reduce red meat and processed meat | Total: 261 g/169 g 1825 g/week/1183 g/week Poultry: 72 g/65 g Red meat: 137 g/76 g Red meat and poultry: 209 g/141 g Processed meat: 52 g/28 g | Above/Above Total: 608%/394%; (6.1×)/(3.9×) the limit Red meat vs. poultry: (2× >/similar) Processed meat |

| Fish and seafood | 200 g/week (0–450 g) ≈29 g/day (0–64 g) | Fish and fish products: 27 g/18 g | Within/Within 100%/100% b (84%/56% vs. 32 g/day midpoint) |

| Eggs | ≤25 g/day ≈3 eggs/week | Eggs, including from foods: 44 g/36 g | Above/Above 176%/144% |

| Nuts and seeds | ≥30 g/day | Nuts and seeds: 8 g/10 g | Below/Below 27%/33% |

| Oils and fats from whole foods (target: ≤25 g/day in addition to nuts and seeds) d | ≤25 g of oil; or ≤100 g of avocado + 8–10 olives; or ≤20 g of oil + 8–10 olives limit/avoid: lard/tallow, tropical fats, butter, and cream | Total: 28 g/23 g Vegetable oils and margarines: 20 g/16 g Butter and other animal fats: 8 g/7 g | Above/Within of limit (≤25 g/day) 112%/92% Above/Above |

| Herbs and spices | Use regularly to minimise salt/sugar intake | No data | Not computable |

| Water and non-alcoholic beverages | ≈1500 mL (mineral) water, unsweetened fruit/herbal teas are the default, Coffee permitted (≤400 mg caffeine/day) Fruit juice occasionally, ≤200 mL/day Avoid SSBs, especially energy drinks | ≈1031 mL/1142 mL of water, tea Water: 925 mL/day/970 mL/day Tea: 106 mL/172 mL Coffee: 91 mL/104 mL Fruit/vegetable juices: 79 mL/46 mL SSBs: 136 mL/63 mL Cocoa and hot chocolate drink: 46 mL/46 mL | Below/Below 69%/76% Caffeine: Not computable Juices: Within/Within SSBs: Above/Above Cocoa and hot choc. drink: Above/Above |

| Alcohol | 0 mL | Alcoholic beverages (mL/day) Wine: 33 mL/18 mL Beer: 183 mL/44 mL Spirits: 17 mL/4 mL | Above/Above Wine: ≈2× in M vs. F Beer: ≈4× in M vs. F Spirits: ≈4× in M vs. F |

| Ultra-processed foods (UPFs) f | Avoid or minimise (see limits in the salt, sugar, and fat rows) | High-sugar foods (sugar, confectionery, cakes, cookies, and desserts): 98 g/107 g High-salt and high-fat foods: no data | Above/Above High-salt and high-fat foods: Not computable |

| Overall diet orientation i, j | <10% E from SFAs <5% E from free sugars g <0.5% E from TFAs <5 g/day salt h | % E from SFAs: No data 7%/7% E from free sugars 0.4–0.5% E from TFAs 11.7 g/8.7 g salt | % E from SFAs: Not computable k Above/Above 140%/140% free sugars Within/Within ≈100%/≈100% TFA Above/Above 234%/174% salt |

4. Discussion

4.1. Quantitative Comparison with the EAT–Lancet Diet and Previous Slovenian FBDGs (Table 1)

4.2. Alignment of Slovenian Intakes with the SNG2025 (Table 2)

4.3. Relation to Earlier Si. Menu Interpretations

4.4. Dietary Gaps and the Health Burden in Slovenia

4.5. Environmental Context

4.6. Interpretation and Implications

4.7. Policy-Relevant Considerations Based on Quantified Gaps

4.8. Implementation Pathways and Dissemination

4.8.1. Culturally Anchored Implementation (Traditional Dishes)

4.8.2. Dissemination and Behaviour-Change Levers

4.8.3. Capacity-Building and Education

4.9. Life-Course Perspective

4.10. Strengths

4.11. Limitations

4.12. Future Research

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DHA | docosahexaenoic acid |

| EPA | eicosapentaenoic acid |

| EAT–Lancet | EAT–Lancet Commission planetary health diet (reference) |

| FBDGs | food-based dietary guidelines |

| MCE | milk-calcium equivalent |

| SFAs | saturated fatty acids |

| SSBs | sugar-sweetened beverages |

| TFAs | trans fatty acids |

| UPFs | ultra-processed foods |

| SNG2025 | Slovenian Nutrition Guidelines 2025 |

| WFPB | whole-food, plant-based |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Fras, Z.; Jug, B.; Jakše, B.; Kreft, S.; Mikec, N.; Malek, Ž.; Bavec, M.; Vovk, A.; Frelih-Larsen, A.; Mis, N.F. Slovenia’s Food-Based Dietary Guidelines 2024: Eating for Health and the Planet. Foods 2024, 13, 3026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fras, Z.; Jakše, B.; Kreft, S.; Malek, Ž.; Kamin, T.; Tavčar, N.; Fidler Mis, N. The Activities of the Slovenian Strategic Council for Nutrition 2023/24 to Improve the Health of the Slovenian Population and the Sustainability of Food: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willett, W.; Rockström, J.; Loken, B.; Springmann, M.; Lang, T.; Vermeulen, S.; Garnett, T.; Tilman, D.; DeClerck, F.; Wood, A.; et al. Food in the Anthropocene: The EAT–Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. Lancet 2019, 393, 447–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidler Mis, N.; Jakše, B.; Kreft, S.; Jug, B.; Vovk, A.; Fras, Z. Eating for Health and the Planet. Slov. Nutr. Guidel. 2025; submitted. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Public Health of Slovenia 12 Steps to Healthy Eating: Recommendations for Healthy Eating. Available online: https://nijz.si/publikacije/12-korakov-do-zdravega-prehranjevanja/ (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Food-Based Dietary Guidelines—Slovenia. Available online: https://www.fao.org/nutrition/education/food-dietary-guidelines/regions/countries/slovenia/en (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- Hlastan Ribič, C.; Orlič Belšak, A. The Healthy Plate; National Institute of Publich Health of Slovenia: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2009; ISBN 978-961-6659-57-4. [Google Scholar]

- Gregorič, M.; Hristov, H.; Blaznik, U.; Koroušić Seljak, B.; Delfar, N.; Pravst, I. Dietary Intakes of Slovenian Adults and Elderly: Design and Results of the National Dietary Study SI. Menu 2017/18. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seljak, B.K.; Valenčič, E.; Hristov, H.; Hribar, M.; Lavriša, Ž.; Kušar, A.; Žmitek, K.; Krušič, S.; Gregorič, M.; Blaznik, U.; et al. Inadequate Intake of Dietary Fibre in Adolescents, Adults, and Elderlies: Results of Slovenian Representative SI. Menu Study. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pravst, I.; Lavriša, Ž.; Hribar, M.; Hristov, H.; Kvarantan, N.; Seljak, B.K.; Gregorič, M.; Blaznik, U.; Gregorič, N.; Zaletel, K.; et al. Dietary Intake of Folate and Assessment of the Folate Deficiency Prevalence in Slovenia Using Serum Biomarkers. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hribar, M.; Hristov, H.; Lavriša, Ž.; Seljak, B.K.; Gregorič, M.; Blaznik, U.; Žmitek, K.; Pravst, I. Vitamin D Intake in Slovenian Adolescents, Adults, and the Elderly Population. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavriša, Ž.; Hristov, H.; Hribar, M.; Koroušić Seljak, B.; Gregorič, M.; Blaznik, U.; Zaletel, K.; Oblak, A.; Osredkar, J.; Kušar, A.; et al. Dietary Iron Intake and Biomarkers of Iron Status in Slovenian Population: Results of SI.Menu/Nutrihealth Study. Nutrients 2022, 14, 5144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavriša, Ž.; Hristov, H.; Hribar, M.; Žmitek, K.; Kušar, A.; Koroušić Seljak, B.; Gregorič, M.; Blaznik, U.; Gregorič, N.; Zaletel, K.; et al. Dietary Intake and Status of Vitamin B12 in Slovenian Population. Nutrients 2022, 14, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kugler, S.; Blaznik, U.; Rehberger, M.; Zaletel, M.; Korošec, A.; Somrak, M.; Oblak, A.; Pravst, I.; Hribar, M.; Kušar, A.; et al. Twenty-four hour urinary sodium and potassium excretion in adult population of Slovenia: Results of the Manjsoli.si/2022 study. Public Health Nutr. 2024, 27, e163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Public Health of Slovenia. Health Statistical Yearbook of Slovenia. 2020. Available online: https://nijz.si/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/zdravstveni_statisticni_letopis_2020.pdf (accessed on 27 May 2023).

- Zadnik, V.; Primic Zakelj, M.; Lokar, K.; Jarm, K.; Ivanus, U.; Zagar, T. Cancer burden in Slovenia with the time trends analysis. Radiol. Oncol. 2017, 51, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Public Health of Slovenia. Circulatory Diseases (Heart and Vessel Diseases). Available online: https://www.dlib.si/details/URN:NBN:SI:DOC-SEZS7U8Q?&language=eng (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- Working Group III Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg3/downloads/report/IPCC_AR6_WGIII_FullReport.pdf (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Poore, J.; Nemecek, T. Reducing food’s environmental impacts through producers and consumers. Science 2018, 360, 987–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zupanič, N.; Hribar, M.; Hristov, H.; Lavriša, Ž.; Kušar, A.; Gregorič, M.; Blaznik, U.; Seljak, B.K.; Golja, P.; Vidrih, R.; et al. Dietary Intake of trans Fatty Acids in the Slovenian Population. Nutrients 2021, 13, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institut Jožef Stefan—Computer Systems Department. Computer Web-Based Software: The Open Platform for Clinical Nutrition (OPEN). Available online: http://opkp.si/en_GB/cms/introduction (accessed on 7 February 2024).

- Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition Carbohydrates and Health. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/445503/SACN_Carbohydrates_and_Health.pdf (accessed on 13 January 2020).

- World Health Organization. Guideline: Sugars Intake for Adults and Children. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/149782/9789241549028_eng.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 22 July 2019).

- World Health Organization. Sodium Reduction. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/salt-reduction (accessed on 17 November 2023).

- Storz, M.A. What makes a plant-based diet? a review of current concepts and proposal for a standardized plant-based dietary intervention checklist. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 76, 789–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad Fuzi, S.F.; Koller, D.; Bruggraber, S.; Pereira, D.I.A.; Dainty, J.R.; Mushtaq, S. A 1-h time interval between a meal containing iron and consumption of tea attenuates the inhibitory effects on iron absorption: A controlled trial in a cohort of healthy UK women using a stable iron isotope. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 106, 1413–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Disler, P.B.; Lynch, S.R.; Charlton, R.W.; Torrance, J.D.; Bothwell, T.H.; Walker, R.B.; Mayet, F. The effect of tea on iron absorption. Gut 1975, 16, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurrell, R.F.; Reddy, M.; Cook, J.D. Inhibition of non-haem iron absorption in man by polyphenolic-containing beverages. Br. J. Nutr. 1999, 81, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, M.; Rosado, J.L.; Allen, L.H.; Abrams, S.; García, O.P. The efficacy of a local ascorbic acid-rich food in improving iron absorption from Mexican diets: A field study using stable isotopes. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2003, 78, 436–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeifer, M.; Siuka, D.; Pravst, I. Recommendations for Cholecalciferol (Vitamin D3) Replacement During Periods of Respiratory Infections and for Cholecalciferol Replacement in Individuals with COVID-19. Available online: https://www.kclj.si/dokumenti/FINAL_Okt_2020_PRIPOROCILA_VITAMIN_D_in_covid-19_za_infektologe.pdf (accessed on 22 February 2022).

- National Institute of Public Health of Slovenia. Reference Values for Energy Intake and Nutrient Intake. Available online: https://www.nijz.si/sites/www.nijz.si/files/uploaded/referencne_vrednosti_2020_3_2.pdf (accessed on 7 February 2024).

- German Nutrition Society; Austrian Nutrition Society; Society for Nutrition Research; Swiss Nutrition Association. Ergaenzlieferung D-A-CH Referenzwerte für die Nährstoffzufuhr (Reference Values for Nutrient Intake), 4th ed.; The German Nutrition Society (DGE): Frankfurt, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, S.; Oliveira, L.; Pereira, A.; Costa, M.d.C.; Raposo, A.; Saraiva, A.; Magalhães, B. Exploring Vitamin B12 Supplementation in the Vegan Population: A Scoping Review of the Evidence. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribič, C.H.; Zakotnik, J.M.; Vertnik, L.; Vegnuti, M.; Cappuccio, F.P. Salt intake of the Slovene population assessed by 24 h urinary sodium excretion. Public Health Nutr. 2010, 13, 1803–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, A.S.; Russo-Batterham, D.; Doyle, K.; Tescari, E. Time to consider more than just calcium? The impact on protein, riboflavin, vitamin B12 and iodine intake of replacing cows’ milk with plant-based milk-like drinks—An Australian usual intake dietary modelling study. Eur. J. Nutr. 2025, 64, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, W.J.; Fresán, U. International Analysis of the Nutritional Content and a Review of Health Benefits of Non-Dairy Plant-Based Beverages. Nutrients 2021, 13, 842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medici, E.; Craig, W.J.; Rowland, I. A Comprehensive Analysis of the Nutritional Composition of Plant-Based Drinks and Yogurt Alternatives in Europe. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsing, R.; Santo, R.; Kim, B.F.; Altema-Johnson, D.; Wooden, A.; Chang, K.B.; Semba, R.D.; Love, D.C. Dairy and Plant-Based Milks: Implications for Nutrition and Planetary Health. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2023, 10, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, M.A.; Domingo, N.G.G.; Colgan, K.; Thakrar, S.K.; Tilman, D.; Lynch, J.; Azevedo, I.L.; Hill, J.D. Global food system emissions could preclude achieving the 1.5° and 2 °C climate change targets. Science 2020, 370, 705–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zupanič, N.; Hribar, M.; Mis, N.F.; Pravst, I. Free sugar content in pre-packaged products: Does voluntary product reformulation work in practice? Nutrients 2019, 11, 2577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. A Public Health Perspective on Zero- and Low-Alcohol Beverages. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/366740/9789240072152-eng.pdf (accessed on 4 April 2025).

- Eilander, A.; Harika, R.K.; Zock, P.L. Intake and sources of dietary fatty acids in Europe: Are current population intakes of fats aligned with dietary recommendations? Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2015, 117, 1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, A.J.; Stevenson, J.; Pettit, J.; Jasthi, B.; Byhre, T.; Harnack, L. Assessing the Nutrient Content of Plant-Based Milk Alternative Products Available in the United States. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2025, 125, 515–527.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brusati, M.; Baroni, L.; Rizzo, G.; Giampieri, F.; Battino, M. Plant-Based Milk Alternatives in Child Nutrition. Foods 2023, 12, 1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walther, B.; Guggisberg, D.; Badertscher, R.; Egger, L.; Portmann, R.; Dubois, S.; Haldimann, M.; Kopf-Bolanz, K.; Rhyn, P.; Zoller, O.; et al. Comparison of nutritional composition between plant-based drinks and cow’s milk. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 988707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberritter, H.; Schäbethal, K.; Von Ruesten, A.; Boeing, H. Der DGE-Ernährungskreis—Darstellung und Basis der lebensmittelbezogenen Empfehlungen der DGE. Ernahr. Umsch. 2013, 60, 24–29. [Google Scholar]

- Blomhoff, R.; Andersen, R.; Arnesen, E.K.; Christensen, J.J.; Eneroth, H.; Erkkola, M.; Gudanaviciene, I.; Halldórsson, Þ.I.; Høyer-Lund, A.; Lemming, E.W.; et al. Nordic Nutrition Recommendations. 2023. Available online: https://pub.norden.org/nord2023-003/nord2023-003.pdf (accessed on 16 July 2023).

- Ministry of Food, Agricultureand Fisheries of Denmark. The Danish Official Dietary Guidelines. Available online: https://en.fvm.dk/news-and-contact/focus-on/the-danish-official-dietary-guidelines (accessed on 2 May 2024).

- Deutsche Gesellschaft für Ernährung e. V. DGE Nutrition Circle. Available online: https://www.dge.de/gesunde-ernaehrung/gut-essen-und-trinken/dge-ernaehrungskreis/ (accessed on 2 May 2024).

- Federal Ministry of Labour, Social Affairs, Health, Care and Consumer Protection. Österreichische Ernährungsempfehlungen. Available online: https://www.sozialministerium.gv.at/Themen/Gesundheit/Ernährung/Österreichische-Ernährungsempfehlungen-NEU.html (accessed on 17 June 2025).

- Government of Canada. Canada’s Dietary Guidelines. Available online: https://food-guide.canada.ca/sites/default/files/artifact-pdf/CDG-EN-2018.pdf (accessed on 21 February 2024).

- Pan, B.; Ge, L.; Lai, H.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Yin, M.; Li, S.; Tian, J.; Yang, K.; Wang, J. Association of soft drink and 100% fruit juice consumption with all-cause mortality, cardiovascular diseases mortality, and cancer mortality: A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 62, 8908–8919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, F.; Liu, Q.; Zhou, Q.; Xiao, P.; Bai, Y.; Wu, T.; Xia, L. Dietary salt intake and cardiovascular outcomes: An umbrella review of meta-analyses and dose-response evidence. Ann. Med. 2025, 57, 2582065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, M.M.; Gamage, E.; Du, S.; Ashtree, D.N.; McGuinness, A.J.; Gauci, S.; Baker, P.; Lawrence, M.; Rebholz, C.M.; Srour, B.; et al. Ultra-processed food exposure and adverse health outcomes: Umbrella review of epidemiological meta-analyses. BMJ 2024, 384, e077310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Chen, B.; Li, J.; Yuan, X.; Li, J.; Wang, W.; Dai, T.; Chen, H.; Wang, Y.; et al. Dietary sugar consumption and health: Umbrella review. BMJ 2023, 381, e071609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregorič, M.; Blaznik, U.; Fajdiga Turk, V.; Delfar, N.; Korošec, A.; Lavtar, D.; Zaletel, M.; Koroušić Seljak, B.; Golja, P.; Zdešar Kotnik, K.; et al. Various Aspects of the Diet of the Inhabitants of Slovenia: Aged from 3 Months to 74 Years. Available online: https://nijz.si/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/razlicni_vidiki_prehranjevanja_prebivalcev_slovenije.pdf (accessed on 6 May 2020).

- Kobe, H.; Štimec, M.; Ribič, C.H.; Fidler Mis, N.; Ribic, C.H.; Mis, F. Food intake in Slovenian adolescents and adherence to the Optimized Mixed Diet: A nationally representative study. Public Health Nutr. 2012, 15, 600–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidler Mis, N.; Kobe, H.; Štimec, M. Dietary intake of macro-and micronutrients in Slovenian adolescents: Comparison with reference values. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2012, 61, 305–313. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe No level of Alcohol Consumption Is Safe for Our Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/news/item/04-01-2023-no-level-of-alcohol-consumption-is-safe-for-our-health (accessed on 2 November 2023).

- National Institute of Public Health of Slovenia. Alcohol Policy in Slovenia. Available online: https://nijz.si/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/alcohol_policy_in_slovenia_final.pdf (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- Statistical Office of the Republic of Slovenia (SURS). Gross Domestic Product, Other Aggregates of National Accounts and Employment, Slovenia. 2016. Available online: https://www.stat.si/StatWeb/en/News/Index/6824 (accessed on 6 September 2025).

- European Commission. Slovenia: Country Health Profile. 2021. Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/social-issues-migration-health/slovenia-country-health-profile-2021_1313047c-en (accessed on 9 September 2023).

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; World Health Organization. Sustainable Healthy Diets Guiding Principles. Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/03bf9cde-6189-4d84-8371-eb939311283f/content (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Canales Holzeis, C.; Fears, R.; Moughan, P.J.; Benton, T.G.; Hendriks, S.L.; Clegg, M.; ter Meulen, V.; von Braun, J. Food systems for delivering nutritious and sustainable diets: Perspectives from the global network of science academies. Glob. Food Sec. 2019, 21, 72–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Action Framework for Developing and Implementing Public Food Procurement and Service Policies for a Healthy Diet. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240018341 (accessed on 6 September 2025).

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; International Fund for Agricultural Development; United Nations International Children’s Fund; World Food Programme; WHO. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2023; The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World (SOFI); FAO; IFAD; UNICEF; WFP; WHO: Rome, Italy, 2023; 316p.

- United Nations International Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Guidance Framework to Support Healthier Food Retail Environments for Children: A Practical Tool for Nutrition and Children’s Rights in the Food Retail Sector. Available online: https://www.nbim.no/contentassets/ea09c471019544d5b4d089849a443e13/guidance-framework-final.pdf (accessed on 6 September 2025).

- International Agency for Research on Cancer. NOURISHING Nutrition Policy Framework: Ten Areas for Action to Promote Healthy Diets and Reduce Obesity. Available online: https://www.wcrf.org/research-policy/policy/nutrition-policy/nourishing-framework/ (accessed on 6 September 2025).

- Zupanič, N.; Hristov, H.; Gregorič, M.; Blaznik, U.; Delfar, N.; Seljak, B.K.; Ding, E.L.; Mis, N.F.; Pravst, I. Total and Free Sugars Consumption in a Slovenian Population Representative Sample. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamin, T.; Seljak, B.K.; Mis, N.F. Water Wins, Communication Matters: School-Based Intervention to Reduce Intake of Sugar-Sweetened Beverages and Increase Intake of Water. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, M.A.; Springmann, M.; Hill, J.; Tilman, D. Multiple health and environmental impacts of foods. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 23357–23362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogataj, J. The Food and Cooking of Slovenia: Traditions, Ingredients, Tastes, Techniques, over 60 Classic Recipes; Aquamarine, cop. 2020; Lorenz Books: London, UK, 2020; ISBN 978-1-903-14160-1. [Google Scholar]

- Government Communication Office of Republic of Slovenia. The Slovenian Presidency Recipe Book. Available online: https://www.slovenia.info/uploads/publikacije/knjiga_receptov_predsedovanje_2021/ENG_02_06_2021_web_The_Slovenian_Presidency_Recipe_Book_.pdf (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- Avelino, D.C.; Lin, C.A.; Waring, M.E.; Barbosa, A.J.; Duffy, V.B. Assessing the Reach and Engagement Effectiveness of Disseminating Food and Nutrition Information on Social Media Channels. Foods 2024, 13, 2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarke, N.; Pechey, E.; Shemilt, I.; Pilling, M.; Roberts, N.W.; Marteau, T.M.; Jebb, S.A.; Hollands, G.J. Calorie (energy) labelling for changing selection and consumption of food or alcohol. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2025, 2025, CD014845. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Nudges to Promote Healthy Eating in Schools: Policy Brief. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240051300 (accessed on 30 December 2025).

- O’Brien, K.; MacDonald-Wicks, L.; Heaney, S.E. A Scoping Review of Food Literacy Interventions. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manna, A.; Vidgen, H.; Gallegos, D. Examining the effectiveness of food literacy interventions in improving food literacy behavior and healthy eating among adults belonging to different socioeconomic groups- a systematic scoping review. Syst. Rev. 2024, 13, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermingham, K.M.; Linenberg, I.; Polidori, L.; Asnicar, F.; Arrè, A.; Wolf, J.; Badri, F.; Bernard, H.; Capdevila, J.; Bulsiewicz, W.J.; et al. Effects of a personalized nutrition program on cardiometabolic health: A randomized controlled trial. Nat. Med. 2024, 30, 1888–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seid, A.; Fufa, D.D.; Bitew, Z.W. The use of internet-based smartphone apps consistently improved consumers’ healthy eating behaviors: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Front. Digit. Health 2024, 6, 1282570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pala, D.; Petrini, G.; Bosoni, P.; Larizza, C.; Quaglini, S.; Lanzola, G. Smartphone applications for nutrition Support: A systematic review of the target outcomes and main functionalities. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2024, 184, 105351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, F.; Stewart, C.; Astbury, N.M.; Cook, B.; Aveyard, P.; Jebb, S.A. Replacing meat with alternative plant-based products (RE-MAP): A randomized controlled trial of a multicomponent behavioral intervention to reduce meat consumption. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 115, 1357–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinpour-Niazi, S.; Mirmiran, P.; Hedayati, M.; Azizi, F. Substitution of red meat with legumes in the therapeutic lifestyle change diet based on dietary advice improves cardiometabolic risk factors in overweight type 2 diabetes patients: A cross-over randomized clinical trial. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 69, 592–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celis-Morales, C.; Livingstone, K.M.; Marsaux, C.F.M.; Macready, A.L.; Fallaize, R.; O’Donovan, C.B.; Woolhead, C.; Forster, H.; Walsh, M.C.; Navas-Carretero, S.; et al. Effect of personalized nutrition on health-related behaviour change: Evidence from the Food4Me European randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2017, 46, 578–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katare, B.; Zhao, S. Behavioral interventions to motivate plant-based food selection in an online shopping environment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2319018121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spanish Agency for Food Safety and Nutrition. Healthy and Sustainable Dietary Recommendations Supplemented with Physical Activity Recommendations for the Spanish Population. Available online: https://www.aesan.gob.es/AECOSAN/docs/documentos/nutricion/RECOMENDACIONES_DIETETICAS_EN.pdf (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- Office for Health Improvement and Disparities of United Kindgom. Eatwell Guide. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5bbb790de5274a22415d7fee/Eatwell_guide_colour_edition.pdf (accessed on 29 May 2024).

- Gregorič, M.; Blaznik, U.; Delfar, N.; Zaletel, M.; Lavtar, D.; Koroušić Seljak, B.; Golja, P.; Zdešar Kotnik, K.; Pravst, I.; Fidler Mis, N.; et al. Slovenian national food consumption survey in adolescents, adults and elderly. EFSA Support. Publ. 2019, 16, 1729E. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- National Institute of Public Health of Slovenia. Health Statistical Yearbook of Slovenia 2023. 3. Health Determinants—Risk Factors. Available online: https://nijz.si/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/3.1_Prehranjevanje_2023_Z__.pdf (accessed on 9 September 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Fidler Mis, N.; Jakše, B.; Fras, Z. The Slovenian Nutrition Guidelines 2025: A Comparison with the Prior Slovenian FBDG, Dietary Intake, and the EAT–Lancet Diet. Foods 2026, 15, 524. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15030524

Fidler Mis N, Jakše B, Fras Z. The Slovenian Nutrition Guidelines 2025: A Comparison with the Prior Slovenian FBDG, Dietary Intake, and the EAT–Lancet Diet. Foods. 2026; 15(3):524. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15030524

Chicago/Turabian StyleFidler Mis, Nataša, Boštjan Jakše, and Zlatko Fras. 2026. "The Slovenian Nutrition Guidelines 2025: A Comparison with the Prior Slovenian FBDG, Dietary Intake, and the EAT–Lancet Diet" Foods 15, no. 3: 524. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15030524

APA StyleFidler Mis, N., Jakše, B., & Fras, Z. (2026). The Slovenian Nutrition Guidelines 2025: A Comparison with the Prior Slovenian FBDG, Dietary Intake, and the EAT–Lancet Diet. Foods, 15(3), 524. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15030524