Research on Physicochemical Properties and Taste of Coppa Influenced by Inoculation with Staphylococcus During Air-Drying Process

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Preparation of Staphylococcus and Sampling of Air-Dried Coppa

2.2. Physicochemical Analysis of Coppa During the Air-Drying Process

2.2.1. Water Activity Measurement

2.2.2. pH Value Analysis

2.2.3. Color Evaluation

2.2.4. Texture Analysis

2.3. Sensory Evaluation

2.4. Metabolite Extraction

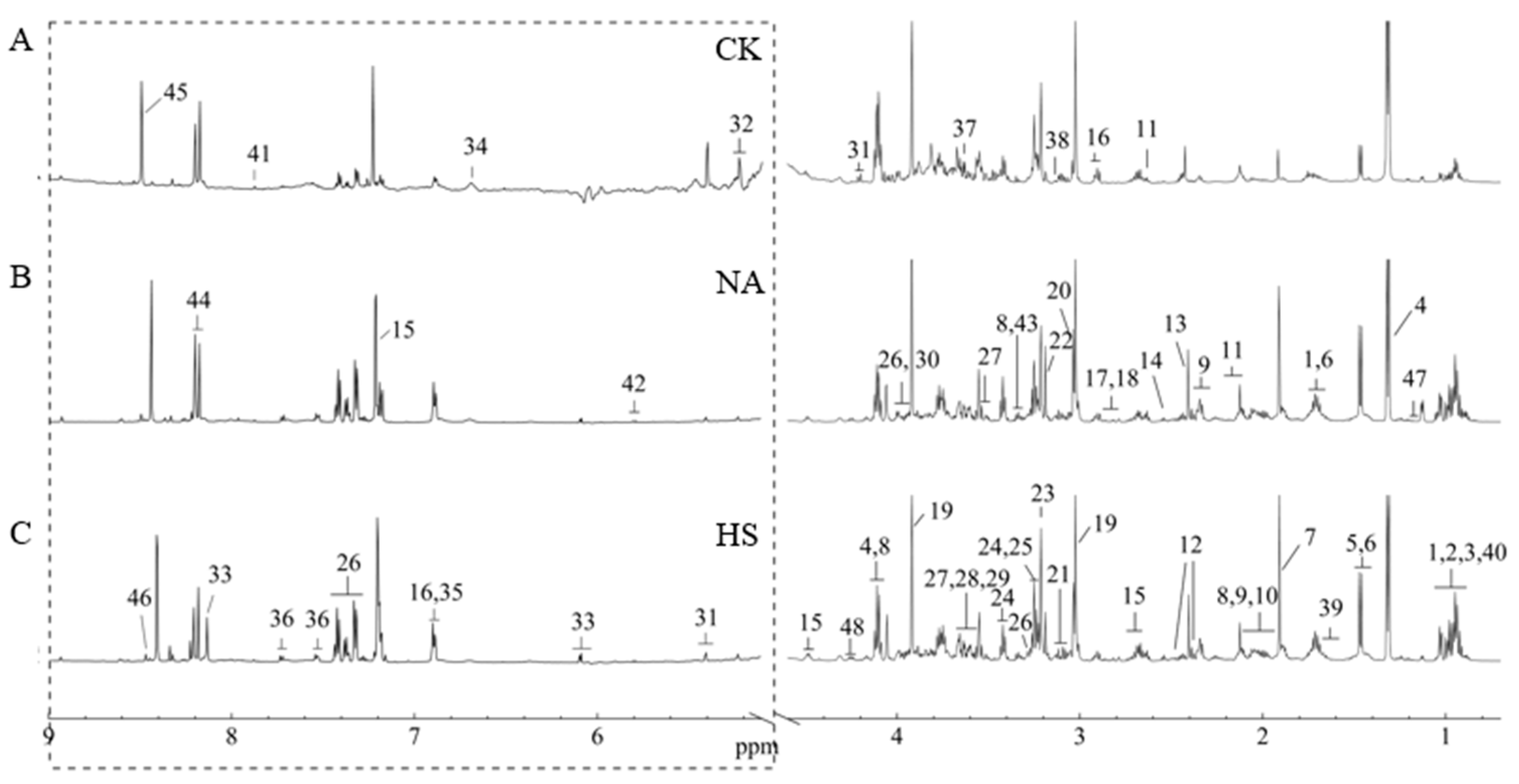

2.5. NMR Analysis

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. The Effects of Staphylococcus Inoculation on the Water Activity of Coppa

3.2. The Effects of Staphylococcus Inoculation on the pH Value of Coppa

3.3. The Effects of Staphylococcus Inoculation on the Color of Coppa

3.4. The Effects of Staphylococcus Inoculation on the Texture of Coppa

3.5. The Effects of Staphylococcus Inoculation on the Taste Sensory Evaluation of Coppa

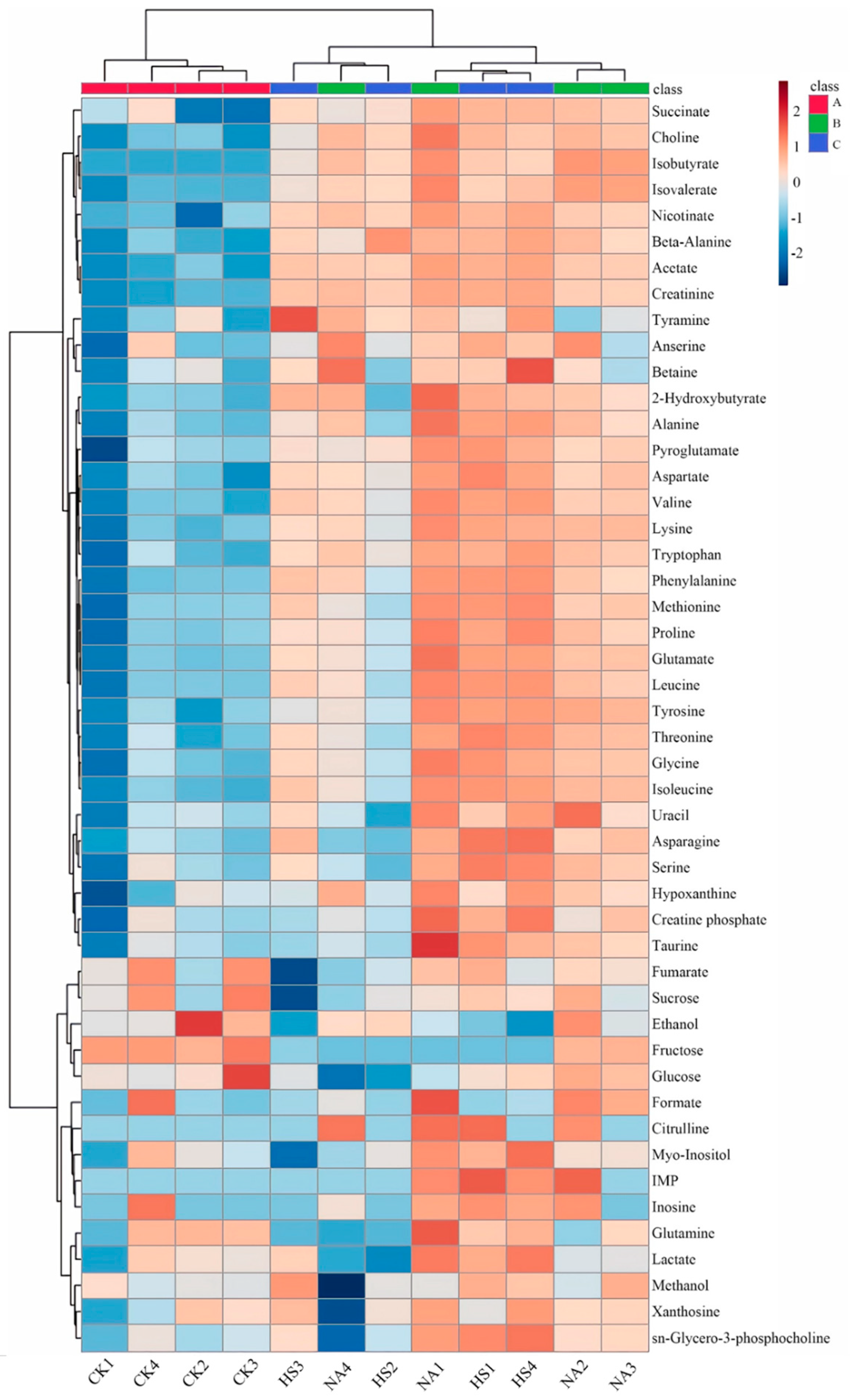

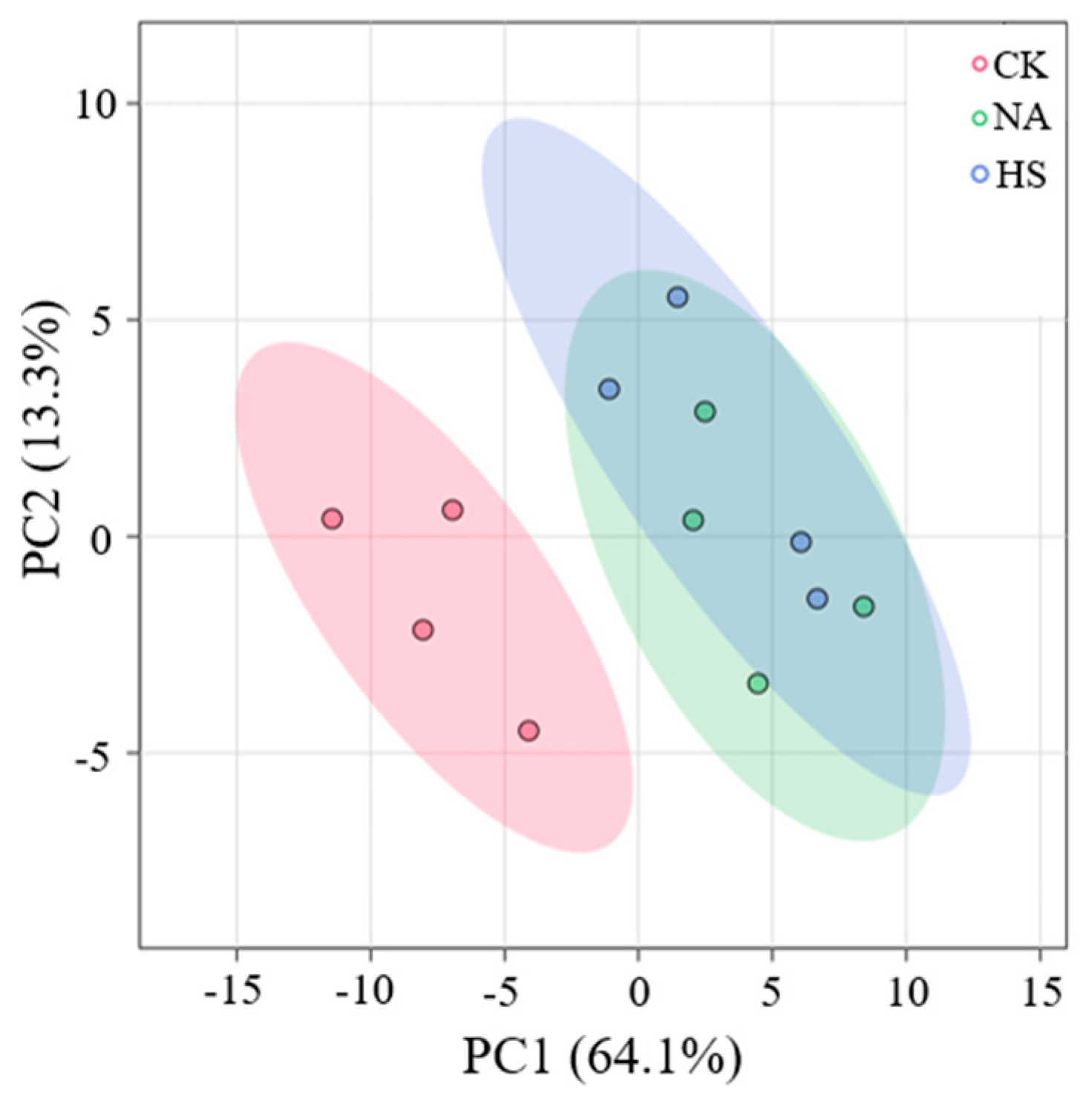

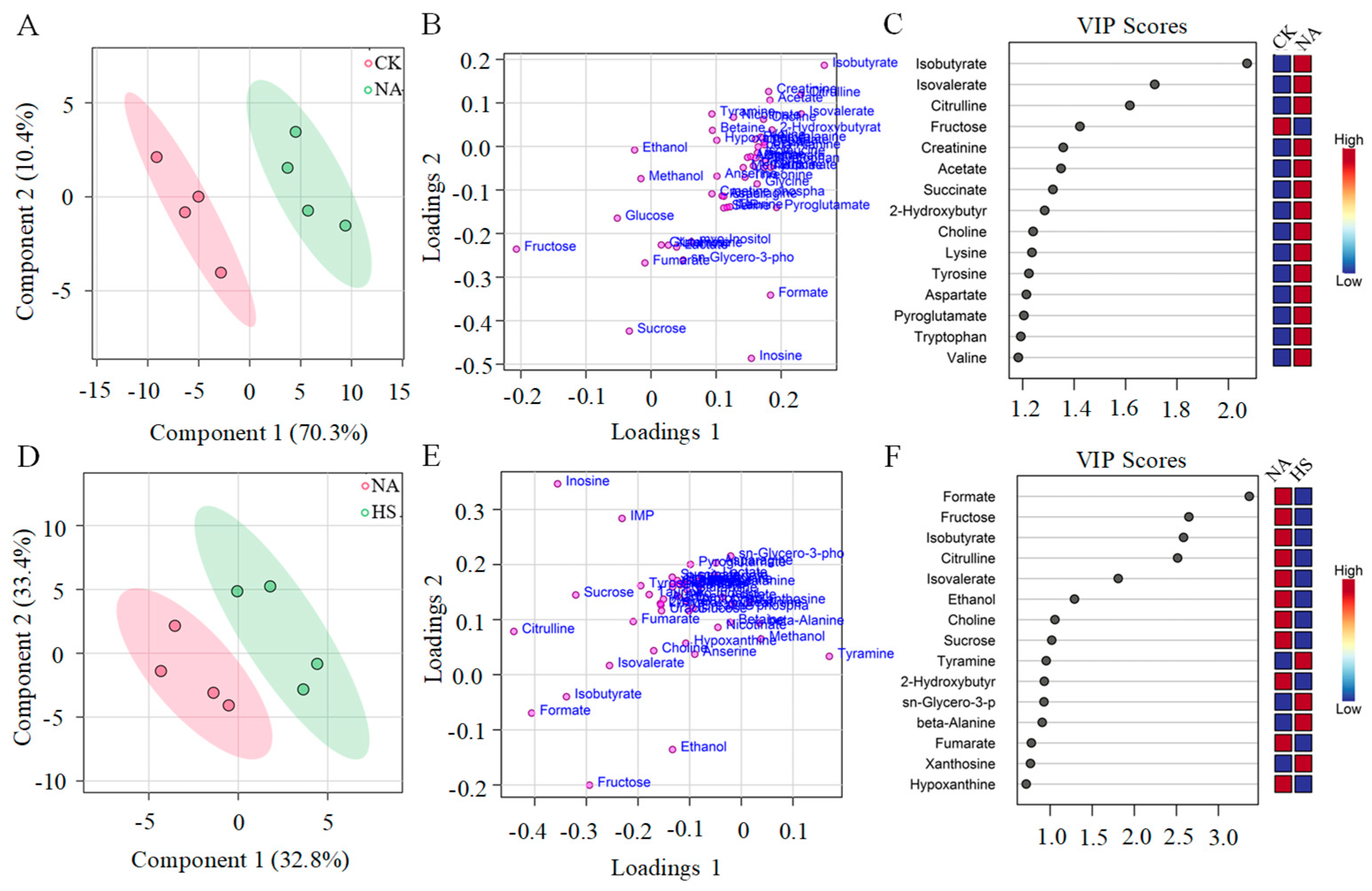

3.6. Metabolite Profile Analysis of Coppa

3.7. Metabolite Composition Analysis and Their Contributions to Taste Development

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, M.; Zhang, X.; Li, J.; Liu, L.; Zhu, Q.; Qu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, S. Identification and in silico simulation on inhibitory platelet-activating factor acetyl hydrolase peptides from dry-cured pork coppa. Foods 2023, 12, 1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leni, G.; Rocchetti, G.; Bertuzzi, T.; Abate, A.; Scansani, A.; Froldi, F.; Prandini, A. Volatile compounds, gamma-glutamyl-peptides and free amino acids as biomarkers of long-ripened protected designation of origin Coppa Piacentina. Food Chem. 2024, 440, 138225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutigliano, M.; Loizzo, P.; Spadaccino, G.; Trani, A.; Tremonte, P.; Coppola, R.; Dilucia, F.; Di Luccia, A.; la Gatta, B. A proteomic study of “Coppa Piacentina”: A typical Italian dry-cured Salami. Food Res. Int. 2023, 166, 112613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hospital, X.F.; Hierro, E.; Arnau, J.; Carballo, J.; Aguirre, J.S.; Gratacós-Cubarsí, M.; Fernández, M. Effect of nitrate and nitrite on Listeria and selected spoilage bacteria inoculated in dry-cured ham. Food Res. Int. 2017, 101, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravyts, F.; Vrancken, G.; D’Hondt, K.; Vasilopoulos, C.; Vuyst, L.D.; Leroy, F. Kinetics of growth and 3-methyl-1-butanol production by meat-borne, coagulase-negative staphylococci in view of sausage fermentation. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2009, 134, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebecchi, A.; Pisacane, V.; Callegari, M.L.; Puglisi, E.; Morelli, L. Ecology of antibiotic resistant coagulase-negative staphylococci isolated from the production chain of a typical Italian salami. Food Control 2015, 53, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.; Zhong, G.; Yang, J.; Zhao, L.; Sun, D.; Tian, Y.; Li, R.; Rong, L. Metagenomic and metabolomic profiling reveals the correlation between the microbiota and flavor compounds and nutrients in fermented sausages. Food Chem. 2022, 375, 131645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, M.; Yu, J.; Yu, J.; Pan, Y.; Ou, Y. Isolation and screening of Staphylococcus xylosus P2 from Chinese bacon: A novel starter culture in fermented meat products. Int. J. Food Eng. 2018, 15, 20180021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vural, Y.; Ferriday, D.; Rogers, P.J. Consumers’ attitudes towards alternatives to conventional meat products: Expectations about taste and satisfaction, and the role of disgust. Appetite 2023, 181, 106394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Andrade, J.C.; Nalério, E.S.; Giongo, C.; de Barcellos, M.D.; Ares, G.; Deliza, R. Consumer sensory and hedonic perception of sheep meat coppa under blind and informed conditions. Meat Sci. 2018, 137, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Pedrouso, M.; Pérez-Santaescolástica, C.; Franco, D.; Carballo, J.; Zapata, C.; Lorenzo, J.M. Molecular insight into taste and aroma of sliced dry-cured ham induced by protein degradation undergone high-pressure conditions. Food Res. Int. 2019, 122, 635–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocchetti, G.; Scansani, A.; Leni, G.; Sigolo, S.; Bertuzzi, T.; Prandini, A. Untargeted metabolomics combined with sensory analysis to evaluate the chemical changes in Coppa Piacentina PDO during different ripening times. Molecules 2023, 28, 2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Sun, C.; Chang, Y.; Li, S.; Zhang, Y.; Fang, Y. Structure analysis and quality evaluation of plant-based meat analogs. J. Texture Stud. 2023, 54, 383–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.Y.; Bai, Y.; Wang, C.; Li, C.B.; Xu, X.L.; Pan, D.D.; Cao, J.X.; Zhou, G.H. 1H NMR-based metabolomics and sensory evaluation characterize taste substances of Jinhua ham with traditional and modern processing procedures. Food Control 2021, 126, 107873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Pan, D.; Sun, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xu, F.; Cao, J. 1H NMR-based metabolomics profiling and taste of stewed pork-hock in soy sauce. Food Res. Int. 2019, 121, 658–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, X.; Ye, Y.; Wang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Pan, D.; Cao, J. Effect of high-pressure treatment on taste and metabolite profiles of ducks with two different vinasse-curing processes. Food Res. Int. 2018, 105, 703–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yang, J.; Gao, H.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, S. Substituting sodium by various metal ions affects the cathepsins activity and proteolysis in dry-cured pork butts. Meat Sci. 2020, 166, 108132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, C.; Wang, Y.; Pan, D.; Zhou, C.; He, J.; Cao, J. Effect of cooking temperature on texture and flavour binding of braised sauce porcine skin. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 56, 1690–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Teng, W.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, J. Polyglycerol polyricinoleate and lecithin stabilized water in oil nanoemulsions for sugaring Beijing roast duck: Preparation, stability mechanisms and color improvement. Food Chem. 2024, 447, 138979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- People’s Republic of China GB/T 16291.1; Sensory Analysis—General Guidance for the Selection, Training and Monitoring of Assessors. Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs: Beijing, China, 2012.

- ISO 8586-1:2012; Sensory Analysis—General Guidelines for the Selection, Training and Monitoring of Selected Assessors and Expert Sensory Assessors. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012.

- ISO 4120:2004; Sensory Analysis—Methodology—Triangle Test, Spanish. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2004.

- Ferreira, N.B.M.; Rodrigues, M.I.; Cristianini, M. Effect of high pressure processing and water activity on pressure resistant spoilage lactic acid bacteria (Latilactobacillus sakei) in a ready-to-eat meat emulsion model. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2023, 401, 110293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Marins, A.R.; De Campos, T.A.F.; Batista, A.F.P.; Correa, V.G.; Peralta, R.M.; Mikcha, J.M.G.; Gomes, R.G.; Feihrmann, A.C. Effect of the addition of encapsulated Lactiplantibacillus plantarum Lp-115, Bifidobacterium animalis spp. Cooked lactis Bb-12 and Lactobacillus acidophilus La-5 for hamburger. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 155, 112946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotterup, J.; Olsen, K.; Knøchel, S.; Tjener, K.; Stahnke, L.H.; Møller, J.K.S. Colour formation in fermented sausages by meat-associated staphylococci with different nitrite- and nitrate-reductase activities. Meat Sci. 2008, 78, 492–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanase, R.; Senda, R.; Matsunaga, Y.; Narukawa, M. Taste characteristics of various amino acid derivatives. J. Nutr. Sci. Vitaminol. 2022, 68, 475–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Duan, W.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, B.; Pu, D.; Tang, Y.; Liu, C. Sensory taste properties of chicken (Hy-Line brown) soup as prepared with five different parts of the chicken. Int. J. Food Prop. 2020, 23, 1804–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdanov, S.; Kilchenmann, V.; Fluri, P.; Buhler, U.; Lavanchy, P. Influence of organic acids and components of essential oils on honey taste. Am. Bee J. 1999, 139, 61–63. [Google Scholar]

| Time (Days) | NA | RS | MS | HS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L* | 0 | 57.67 ± 0.86 Aa | 57.67 ± 0.86 Aa | 57.67 ± 0.86 Aa | 57.67 ± 0.86 Aa |

| 10 | 52.50 ± 2.85 Ab | 53.13 ± 0.54 Ab | 54.08 ± 1.09 Ab | 55.24 ± 0.82 Ab | |

| 20 | 48.20 ± 2.46 Bc | 49.35 ± 0.62 Bc | 50.31 ± 0.28 ABc | 52.29 ± 0.62 Ac | |

| 30 | 38.97 ± 1.27 Bd | 39.38 ± 0.53 Bd | 40.29 ± 0.51 ABd | 41.08 ± 0.62 Ad | |

| 40 | 37.92 ± 0.74 Bd | 38.32 ± 0.46 ABd | 39.13 ± 0.22 Ad | 39.20 ± 0.41 Ae | |

| a* | 0 | 11.74 ± 0.61 Aa | 11.74 ± 0.61 Aa | 11.74 ± 0.61 Aa | 11.74 ± 0.61 Aab |

| 10 | 10.88 ± 0.50 Ba | 12.45 ± 0.33 Aa | 12.69 ± 0.04 Aa | 13.05 ± 0.21 Aa | |

| 20 | 9.66 ± 0.50 Bb | 11.78 ± 0.69 Aa | 12.15 ± 0.39 Aa | 12.34 ± 0.60 Aab | |

| 30 | 9.29 ± 0.44 Bb | 10.65 ± 0.47 ABb | 10.12 ± 0.69 ABc | 11.23 ± 1.19 Ab | |

| 40 | 8.80 ± 0.39 Bb | 10.42 ± 0.37 Ab | 10.77 ± 1.12 Abc | 11.01 ± 0.71 Ab | |

| b* | 0 | 11.45 ± 0.83 Aa | 11.45 ± 0.83 Aa | 11.45 ± 0.83 Aab | 11.45 ± 0.83 Aa |

| 10 | 10.69 ± 0.97 Aab | 10.46 ± 0.74 Aab | 12.02 ± 0.91 Aa | 12.37 ± 1.61 Aa | |

| 20 | 9.71 ± 1.02 Bbc | 9.69 ± 0.06 Bb | 11.30 ± 0.61 Aab | 11.84 ± 0.08 Aa | |

| 30 | 9.40 ± 0.55 Bbc | 9.58 ± 0.31 Bb | 10.66 ± 0.60 Aab | 11.04 ± 0.69 Aa | |

| 40 | 8.75 ± 0.36 Bc | 9.93 ± 0.99 ABb | 10.20 ± 0.65 Ab | 10.86 ± 0.43 Aa |

| Time (Days) | NA | RS | MS | HS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hardness (g) | 0 | 269.39 ± 109.15 Ab | 269.39 ± 109.15 Ab | 269.39 ± 109.15 Ac | 269.39 ± 109.15 Ac |

| 10 | 395.14 ± 176.07 Bab | 291.51 ± 20.06 Bb | 747.85 ± 111.48 Abc | 234.62 ± 94.02 Bc | |

| 20 | 686.53 ± 63.75 BCab | 323.23 ± 61.33 Cb | 982.53 ± 373.30 Bbc | 1606.43 ± 481.26 Ab | |

| 30 | 712.75 ± 99.37 Bab | 540.22 ± 224.60 Bb | 1190.49 ± 845.38 ABab | 1978.77 ± 325.10 Aab | |

| 40 | 796.83 ± 413.30 Ca | 1588.83 ± 265.17 Ba | 1904.28 ± 88.99 ABa | 2260.84 ± 398.98 Aa | |

| Springiness | 0 | 0.20 ± 0.01 Aa | 0.20 ± 0.01 Ab | 0.20 ± 0.01 Aa | 0.20 ± 0.01 Aa |

| 10 | 0.22 ± 0.02 Aa | 0.23 ± 0.01 Aa | 0.22 ± 0.01 Aa | 0.23 ± 0.02 Aa | |

| 20 | 0.21 ± 0.00 Aa | 0.22 ± 0.01 Aab | 0.22 ± 0.00 Aa | 0.21 ± 0.01 Aa | |

| 30 | 0.22 ± 0.02 Aa | 0.20 ± 0.02 Ac | 0.22 ± 0.01 Aa | 0.21 ± 0.01 Aa | |

| 40 | 0.20 ± 0.01 Aa | 0.19 ± 0.02 Abc | 0.22 ± 0.02 Aa | 0.20 ± 0.03 Aa | |

| Cohesiveness | 0 | 0.23 ± 0.00 Aab | 0.23 ± 0.00 Aab | 0.23 ± 0.00 Aa | 0.23 ± 0.00 Ab |

| 10 | 0.21 ± 0.02 Bc | 0.25 ± 0.00 Aa | 0.26 ± 0.01 Aa | 0.27 ± 0.01 Aa | |

| 20 | 0.23 ± 0.00 ABab | 0.25 ± 0.01 Aa | 0.25 ± 0.01 Aa | 0.23 ± 0.02 Bb | |

| 30 | 0.24 ± 0.02 ABa | 0.22 ± 0.01 Bb | 0.25 ± 0.02 Aa | 0.25 ± 0.02 Aab | |

| 40 | 0.24 ± 0.02 Aa | 0.21 ± 0.03 Ab | 0.25 ± 0.03 Aa | 0.25 ± 0.03 Aab | |

| Chewiness | 0 | 12.83 ± 5.88 Ab | 12.83 ± 5.88 Ab | 12.83 ± 5.88 Ac | 12.83 ± 5.88 Ab |

| 10 | 17.93 ± 9.45 Bab | 16.84 ± 1.72 Bb | 41.90 ± 8.94 Abc | 14.65 ± 4.55 Bb | |

| 20 | 33.41 ± 2.70 BCa | 17.29 ± 2.91 Cb | 52.43 ± 19.24 ABabc | 74.40 ± 20.12 Aa | |

| 30 | 21.70 ± 11.89 Bab | 25.02 ± 2.37 Bb | 66.40 ± 51.10 ABab | 108.28 ± 27.73 Aa | |

| 40 | 37.41 ± 16.47 Ba | 65.60 ± 26.63 ABa | 102.66 ± 23.51 Aa | 118.57 ± 52.29 Aa |

| Metabolites | Average ± SD (mg/g) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| CK | NA | HS | |

| 2-hydroxybutyric acid | 0.022 ± 0.007 b | 0.152 ± 0.089 a | 0.106 ± 0.058 ab |

| Choline | 0.051 ± 0.017 b | 0.277 ± 0.086 a | 0.195 ± 0.044 a |

| Citrulline | ND | 0.090 ± 0.069 a | ND |

| Ethanol | 0.030 ± 0.012 a | 0.025 ± 0.007 a | 0.016 ± 0.007 a |

| Formic acid | 0.034 ± 0.025 b | 0.448 ± 0.126 a | 0.031 ± 0.005 b |

| Fructose | 0.285 ± 0.181 a | 0.056 ± 0.065 b | ND |

| Fumaric acid | 0.005 ± 0.002 a | 0.004 ± 0.001 a | 0.003 ± 0.002 a |

| Hypoxanthine | 0.425 ± 0.158 b | 0.761 ± 0.119 a | 0.636 ± 0.156 ab |

| Isobutyric acid | ND | 0.102 ± 0.040 a | 0.025 ± 0.009 b |

| Isovaleric acid | 0.004 ± 0.001 b | 0.107 ± 0.044 a | 0.046 ± 0.014 b |

| Sucrose | 0.216 ± 0.217 a | 0.085 ± 0.095 a | 0.062 ± 0.053 a |

| Tyramine Xanthine | 0.056 ± 0.028 b | 0.101 ± 0.038 ab | 0.146 ± 0.062 a |

| Nucleosides | 0.008 ± 0.003 a | 0.009 ± 0.005 a | 0.011 ± 0.003 a |

| Choline glycerophosphate | 0.252 ± 0.067 a | 0.357 ± 0.198 a | 0.496 ± 0.210 a |

| β-Alanine | 0.043 ± 0.015 b | 0.195 ± 0.051 a | 0.259 ± 0.062 a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Du, J.; Feng, L.; Wang, Y.; Cao, J.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, X.; Wang, W.; Ding, Y.; Zhuang, S.; et al. Research on Physicochemical Properties and Taste of Coppa Influenced by Inoculation with Staphylococcus During Air-Drying Process. Foods 2026, 15, 459. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15030459

Du J, Feng L, Wang Y, Cao J, Wang J, Zhang Y, Tang X, Wang W, Ding Y, Zhuang S, et al. Research on Physicochemical Properties and Taste of Coppa Influenced by Inoculation with Staphylococcus During Air-Drying Process. Foods. 2026; 15(3):459. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15030459

Chicago/Turabian StyleDu, Juanjuan, Linyuan Feng, Ying Wang, Jinxuan Cao, Jinpeng Wang, Yuemei Zhang, Xiaoyan Tang, Wei Wang, Yu Ding, Shuai Zhuang, and et al. 2026. "Research on Physicochemical Properties and Taste of Coppa Influenced by Inoculation with Staphylococcus During Air-Drying Process" Foods 15, no. 3: 459. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15030459

APA StyleDu, J., Feng, L., Wang, Y., Cao, J., Wang, J., Zhang, Y., Tang, X., Wang, W., Ding, Y., Zhuang, S., & Teng, W. (2026). Research on Physicochemical Properties and Taste of Coppa Influenced by Inoculation with Staphylococcus During Air-Drying Process. Foods, 15(3), 459. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15030459