The Effect of Pretreatments and Infrared Drying on the Quality of White Radish Slices

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Raw Materials

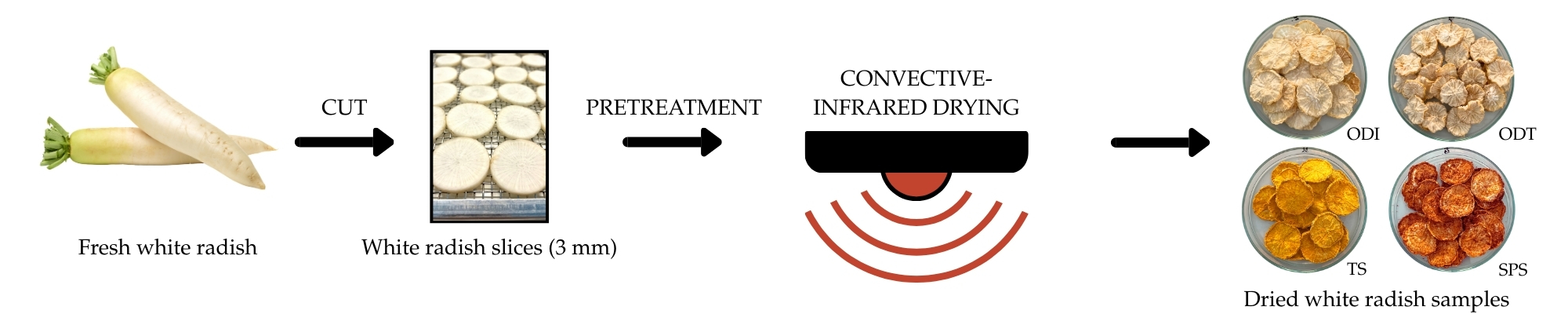

2.2. Pretreatment and Drying Procedure

2.2.1. Blanching

2.2.2. Electro-Physical Methods

2.2.3. Osmotic Dehydration

2.2.4. Coating

2.2.5. Drying

2.3. Analytical Methods

2.3.1. Moisture Content and Water Activity

2.3.2. Shrinkage and Density

2.3.3. Texture

2.3.4. Color Measurement

2.3.5. Vapor Adsorption Capacity (Hygroscopicity)

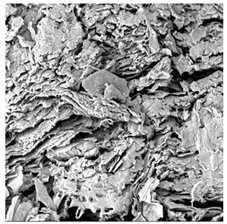

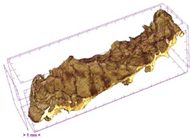

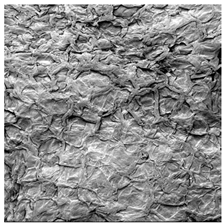

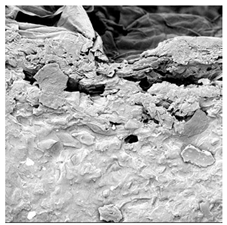

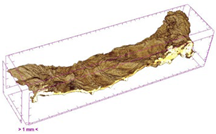

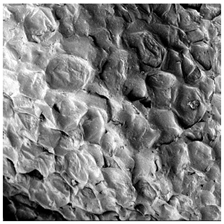

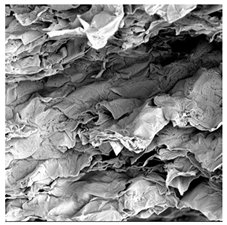

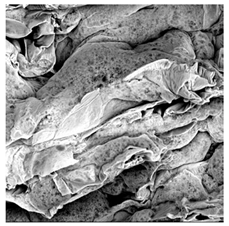

2.3.6. Structure

2.3.7. Thermal Analysis

2.3.8. Total Phenolic Content (TPC) and DPPH Radical Scavenging Activity

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Water Activity and Moisture Content

3.2. Shrinkage, Density, and Texture Properties

3.3. Color

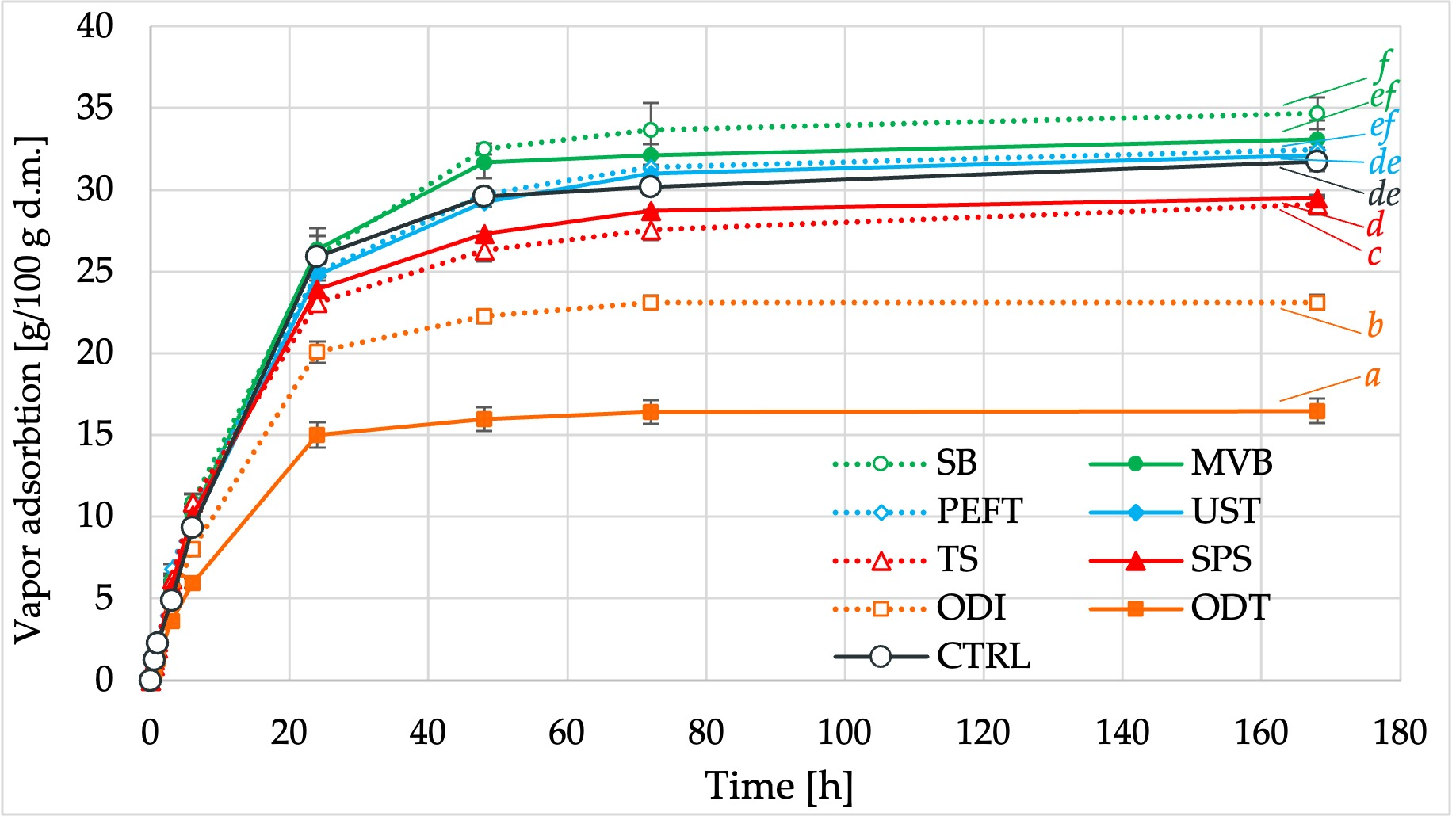

3.4. Vapor Adsorption Capacity

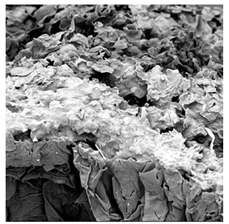

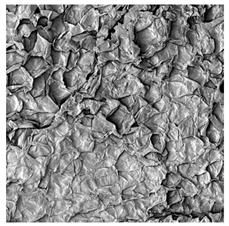

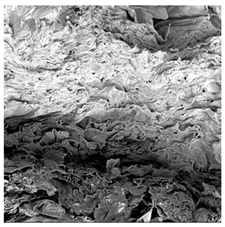

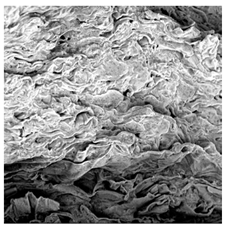

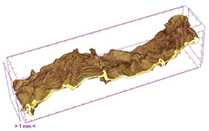

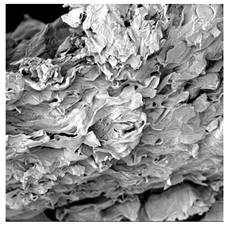

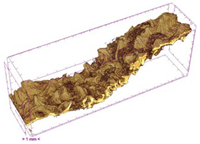

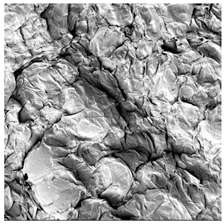

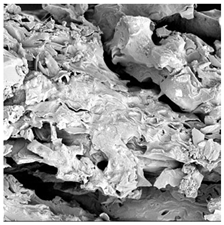

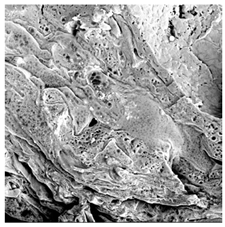

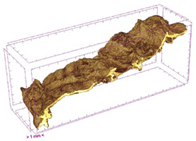

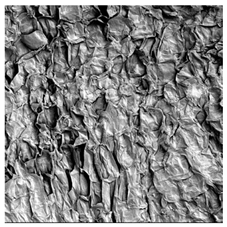

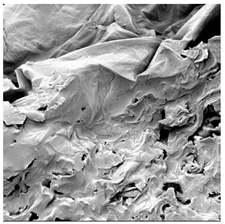

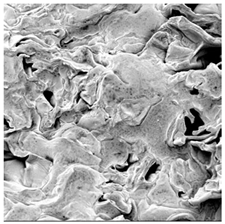

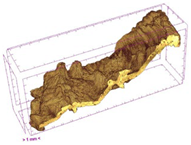

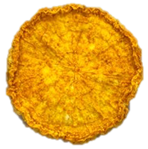

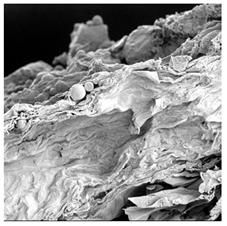

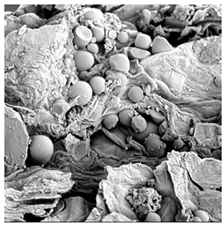

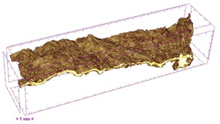

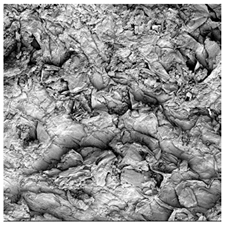

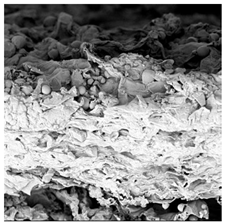

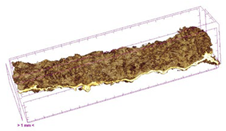

3.5. Structure

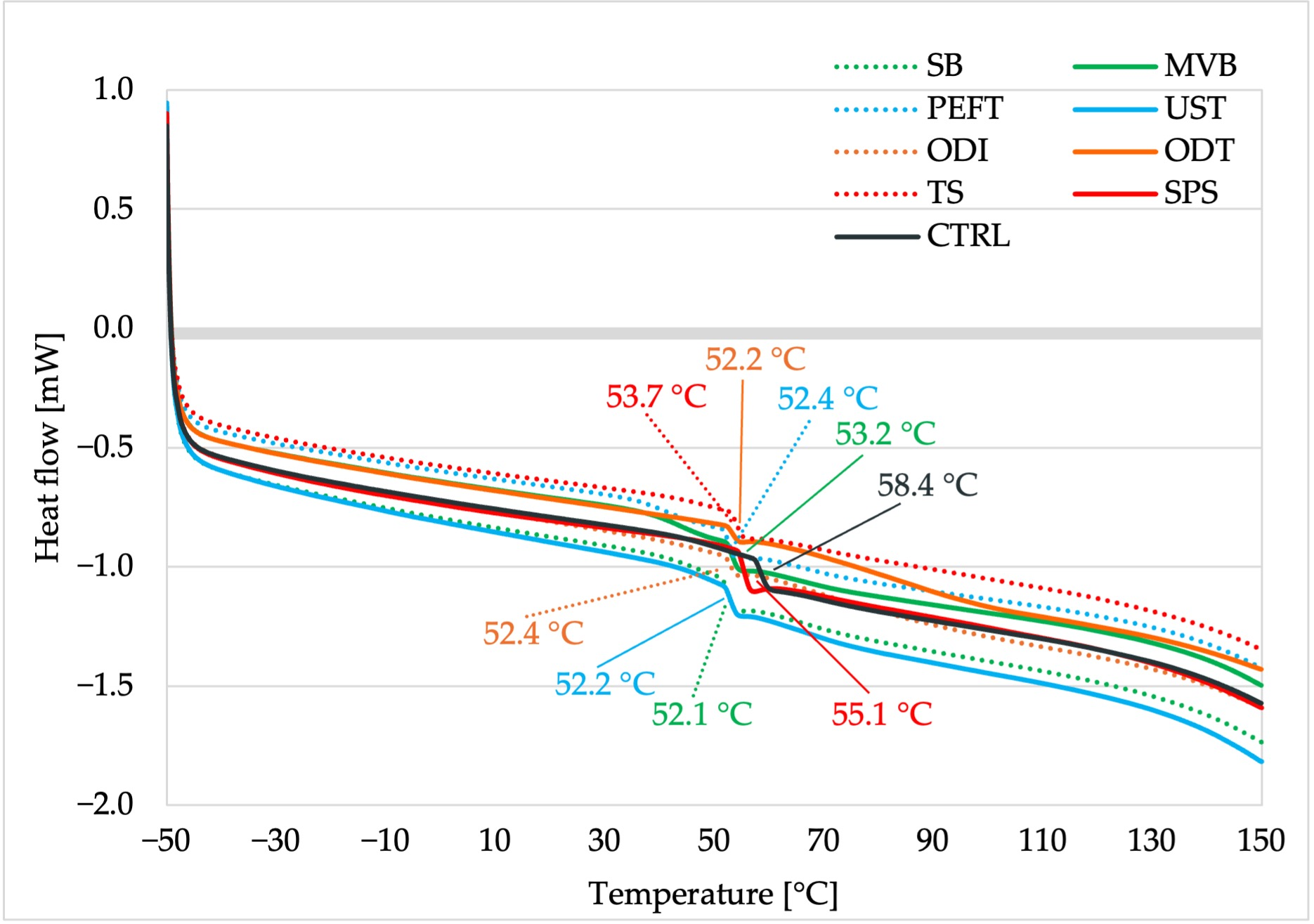

3.6. Thermal Analysis

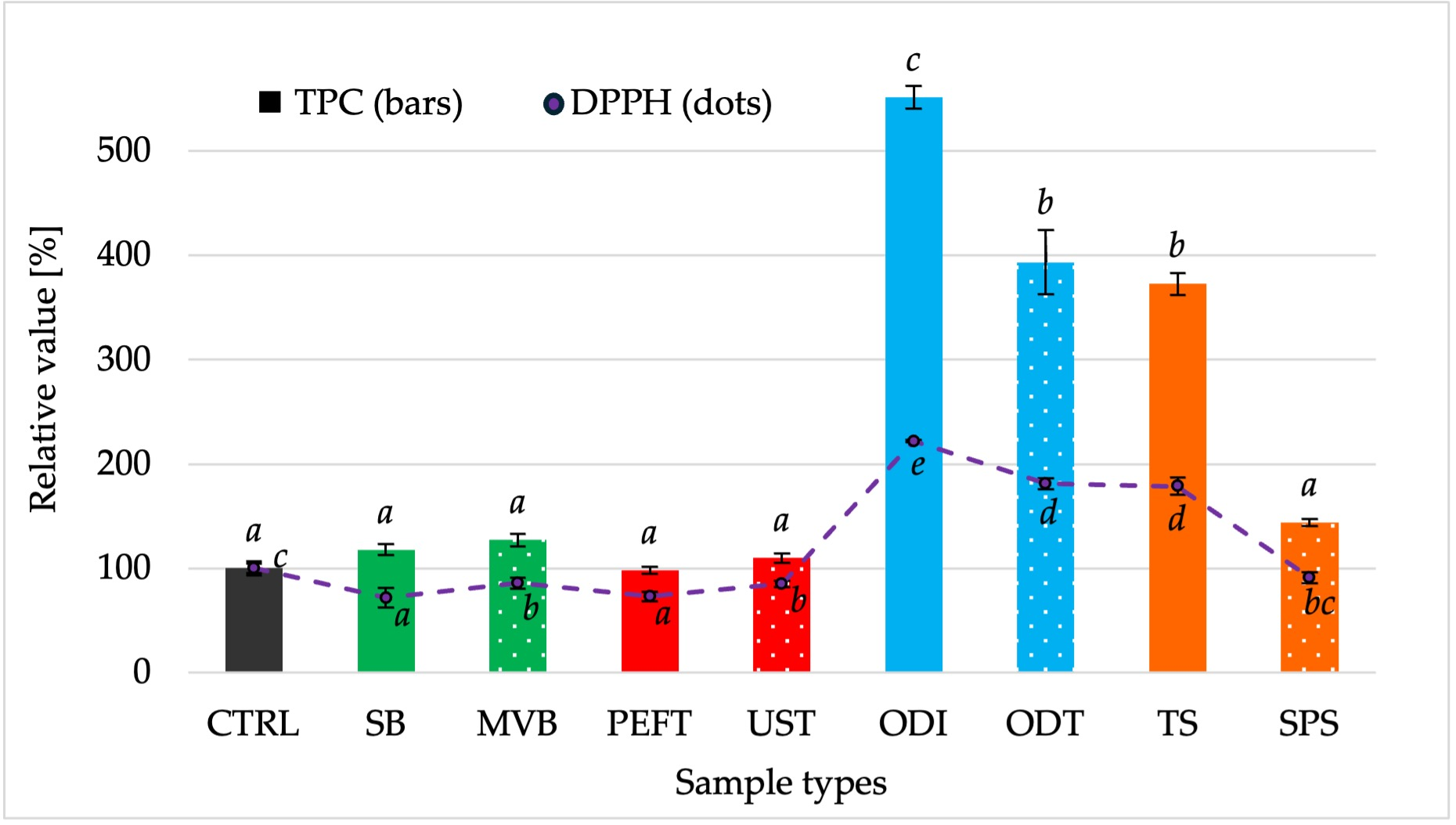

3.7. Antioxidant Activity

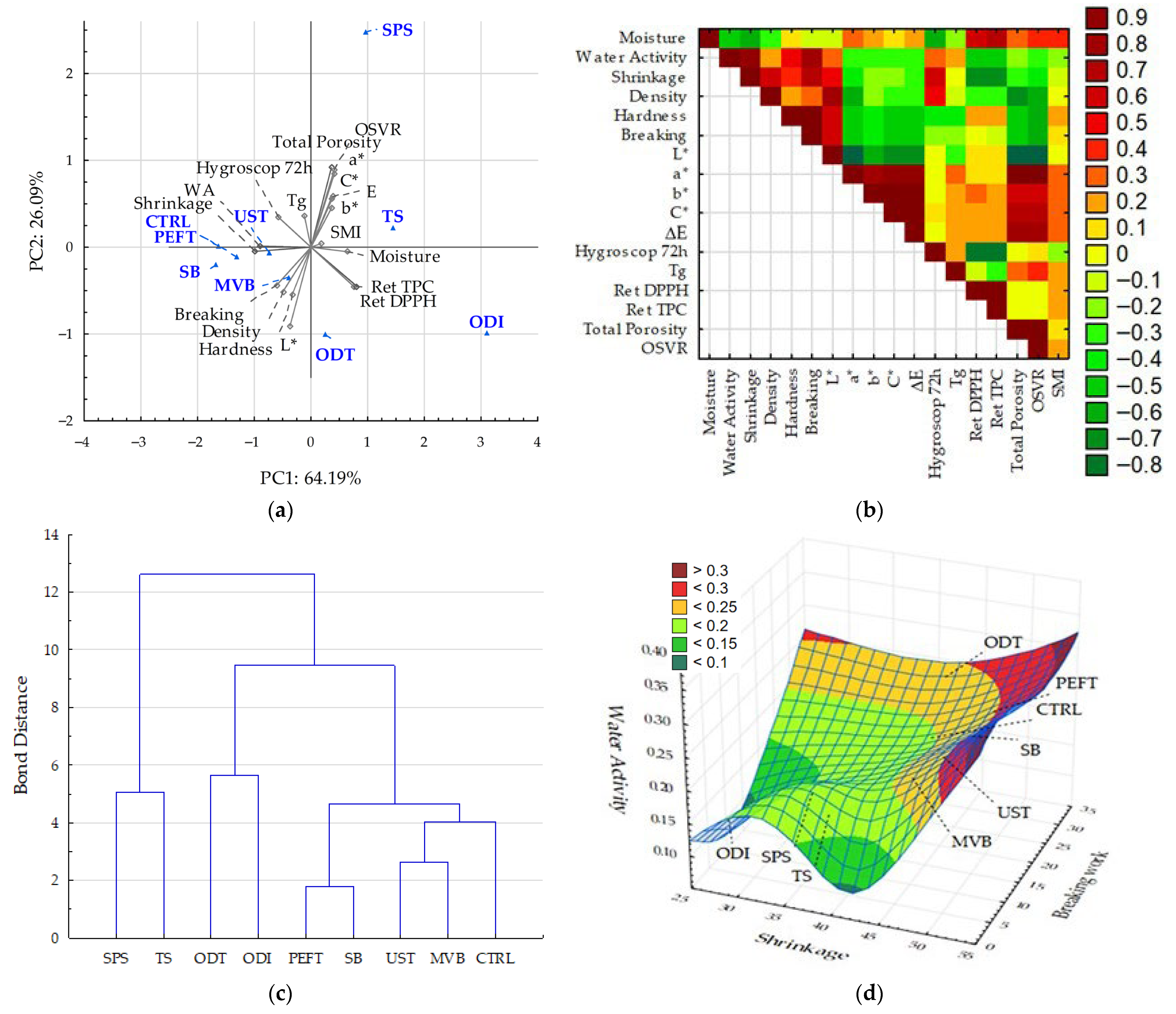

3.8. Discussion of Results with Comprehensive Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Radovich, T.J. Biology and Classification of Vegetables. In Handbook of Vegetables and Vegetable Processing; Siddiq, M., Uebersax, M.A., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: London, UK, 2018; pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- FoodData Central. Available online: https://fdc.nal.usda.gov/fdc-app.html#/food-details/168451/nutrients (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Banihani, S.A. Radish (Raphanus sativus) and Diabetes. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamba, M.; Asllanaj, E.; Raguindin, P.F.; Glisic, M.; Franco, O.H.; Minder, B.; Bussler, W.; Metzger, B.; Kern, H.; Muka, T. Nutritional and Phytochemical Characterization of Radish (Raphanus sativus): A Systematic Review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 113, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyeneche, R.; Roura, S.; Ponce, A.; Vega-Gálvez, A.; Quispe-Fuentes, I.; Uribe, E.; Di Scala, K. Chemical Characterization and Antioxidant Capacity of Red Radish (Raphanus sativus L.) Leaves and Roots. J. Funct. Foods 2015, 16, 256–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, Y.; Nakamura, K.; Asai, Y.; Wada, T.; Tanaka, K.; Matsuo, T.; Okamoto, S.; Meijer, J.; Kitamura, Y.; Nishikawa, A.; et al. Comparison of the Glucosinolate-Myrosinase Systems among Daikon (Raphanus sativus, Japanese White Radish) Varieties. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 2702–2707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beevi, S.S.; Mangamoori, L.N.; Dhand, V.; Ramakrishna, D.S. Isothiocyanate Profile and Selective Antibacterial Activity of Root, Stem, and Leaf Extracts Derived from Raphanus sativus L. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2009, 6, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaafar, N.A.; Ahmed, A.S.; Al-Sandooq, D.L. Detection of Active Compounds in Radish Raphanus sativus L. and Their Various Biological Effects. Plant Arch. 2020, 20, 1647–1650. [Google Scholar]

- Maqbool, H.; Visnuvinayagam, S.; Zynudheen, A.A.; Safeena, M.P.; Kumar, S. Antibacterial Activity of Beetroot Peel and Whole Radish Extract by Modified Well Diffusion Assay. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2020, 9, 1222–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manivannan, A.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, D.S.; Lee, E.S.; Lee, H.E. Deciphering the Nutraceutical Potential of Raphanus sativus—A Comprehensive Overview. Nutrients 2019, 11, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, I.S. The Noble Radish: Past, Present and Future. Trends Plant Sci. 2003, 8, 305–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taniguchi, H.; Muroi, R.; Kobayashi-Hattori, K.; Uda, Y.; Oishi, Y.; Takita, T. Differing Effects of Water-Soluble and Fat-Soluble Extracts from Japanese Radish (Raphanus sativus) Sprouts on Carbohydrate and Lipid Metabolism in Normal and Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Rats. J. Nutr. Sci. Vitaminol. 2007, 53, 261–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishibashi, R.; Numata, T.; Tanigawa, H.; Tsuruta, T. In-situ measurements of drying and shrinkage characteristics during microwave vacuum drying of radish and potato. J. Food Eng. 2022, 323, 110988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Kim, H.J. Vacuum drying kinetics of Asian white radish (Raphanus sativus L.) slices. LWT 2009, 42, 180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayi, P.; Ma, F.Y.; Huang, T.C.; Lee, Y.C.; Kumar, N.; Chen, H.H. Effect of solar radiation and full spectrum artificial sun light drying on the drying characteristics, ultra-structural and textural properties of white radish (Raphanus sativus L.). Sol. Energy 2024, 272, 112465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Han, W.; Wei, B.; Liu, Y.; Gao, L.; Wang, L.; Wang, S.; Zhu, M.; Huo, Z. Drying characteristics of white radish slices under heat pump—Low-temperature regenerative wheel collaborative drying. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2025, 69, 105950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Mesery, H.S.; Abomohra, A.E.F.; Kang, C.U.; Cheon, J.K.; Basak, B.; Jeon, B.H. Evaluation of Infrared Radiation Combined with Hot Air Convection for Energy-Efficient Drying of Biomass. Energies 2019, 12, 2818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaveh, M.; Zomorodi, S.; Ghaysari, B.; El-Mesery, H.S.; Sharifian, F.; ElMesiry, A.H.; Salem, A. Impact of Various Drying Technologies for Evaluation of Drying Kinetics, Energy Consumption, Physical and Bioactive Properties of Rose Flower. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 9245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza, A.U.; Corrêa, J.L.G.; Tanikawa, D.H.; Abrahão, F.R.; Junqueira, J.R.d.J.; Jiménez, E.C. Hybrid Microwave-Hot Air Drying of the Osmotically Treated Carrots. LWT 2022, 156, 113046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbaspour-Gilandeh, Y.; Kaveh, M.; Aziz, M. Ultrasonic-Microwave and Infrared Assisted Convective Drying of Carrot: Drying Kinetic, Quality and Energy Consumption. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 6309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giancaterino, M.; Werl, C.; Jaeger, H. Evaluation of the Quality and Stability of Freeze-Dried Fruits and Vegetables Pre-Treated by Pulsed Electric Fields (PEF). LWT 2024, 191, 115651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adiamo, O.Q.; Eltoum, Y.A.I.; Babiker, E.E. Effects of Gum Arabic Edible Coatings and Sun-Drying on the Storage Life and Quality of Raw and Blanched Tomato Slices. J. Culin. Sci. Technol. 2019, 17, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Venkitasamy, C.; Shen, Q.; McHugh, T.H.; Zhang, R.; Pan, Z. Development of Healthy Crispy Carrot Snacks Using Sequential Infrared Blanching and Hot Air Drying Method. LWT 2018, 97, 469–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzuki, S.U.; Pranoto, Y.; Khumsap, T.; Nguyen, L.T. Effect of Blanching Pretreatment and Microwave-Vacuum Drying on Drying Kinetics and Physicochemical Properties of Purple-Fleshed Sweet Potato. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 58, 2884–2895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nalawade, S.A.; Sinha, A.; Hebbar, H.U. Infrared Based Dry Blanching and Hybrid Drying of Bitter Gourd Slices: Process Efficiency Evaluation. J. Food Process Eng. 2018, 41, e12672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straits Research. Available online: https://straitsresearch.com/report/dehydrated-fruits-and-vegetables-market?utm_source (accessed on 4 August 2025).

- Barakat, H.; Aljutaily, T.; Khalifa, I.; Almutairi, A.S.; Aljumayi, H. Nutritional Properties of Innovatively Prepared Plant-Based Vegan Snack. Processes 2024, 12, 2720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magro, P.C.; Maestro-Gaitán, I.; Blázquez, M.R.; Prieto, J.M.; Iñiguez, F.M.S.; Sobrado, V.C.; Gómez, M.J.R. Determination of Nutritional Signatures of Vegetable Snacks Formulated with Quinoa, Amaranth, or Wheat Flour. Food Chem. 2024, 433, 137370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okpiaifo, G.E.; Dormoy-Smith, B.; Kassas, B.; Gao, Z. Perception and Demand for Healthy Snacks/Beverages among US Consumers Vary by Product, Health Benefit, and Color. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0287232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Association of Official Analytical Chemists. Official Methods of Analysis; Association of Official Analytical Chemists: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, J.; Khalloufi, S.; Martynenko, A.; Van Dalen, G.; Schutyser, M.; Almeida-Rivera, C. Porosity, Bulk Density, and Volume Reduction During Drying: Review of Measurement Methods and Coefficient Determinations. Dry. Technol. 2015, 33, 1681–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, V.L.; Orthofer, R.; Lamuela-Raventós, R.M. Analysis of Total Phenols and Other Oxidation Substrates and Antioxidants by Means of Folin-Ciocalteu Reagent. In Methods in Enzymology; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999; Volume 299, pp. 151–178. [Google Scholar]

- Brand-Williams, W.; Cuvelier, M.E.; Berset, C. Use of a Free Radical Method to Evaluate Antioxidant Activity. LWT 1995, 28, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybak, K.; Wiktor, A.; Witrowa-Rajchert, D.; Parniakov, O.; Nowacka, M. The Quality of Red Bell Pepper Subjected to Freeze-Drying Preceded by Traditional and Novel Pretreatment. Foods 2021, 10, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.H.; Lamsal, B.P.; Balasubramaniam, V. Principles of Food Processing. In Food Processing: Principles and Applications; Clark, S., Jung, S., Lamsal, B., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: London, UK, 2014; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Buvaneswaran, M.; Natarajan, V.; Sunil, C.K.; Rawson, A. Effect of Pretreatments and Drying on Shrinkage and Rehydration Kinetics of Ginger (Zingiber officinale). J. Food Process Eng. 2022, 45, e13972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhao, Y.; Molaveisi, M.; Shi, Q. Effects of Ultrasonic Pre-Treatment on the Porosity, Shrinkage Behaviors, and Heat Pump Drying Kinetics of Scallop Adductors Considering Shrinkage Correction. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2024, 61, 104900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavkov, I.; Radojčin, M.; Stamenković, Z.; Kešelj, K.; Tylewicz, U.; Sipos, P.; Ponjičan, O.; Sedlar, A. Effects of Osmotic Dehydration on the Hot Air Drying of Apricot Halves: Drying Kinetics, Mass Transfer, and Shrinkage. Processes 2021, 9, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghannya, J.; Gorbani, R.; Ghanbarzadeh, B. Shrinkage of Mirabelle Plum during Hot Air Drying as Influenced by Ultrasound-Assisted Osmotic Dehydration. Int. J. Food Prop. 2016, 19, 1093–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thibault, B.; Aghajanzadeh, S.; Khalloufi, S. Comparative Analysis of Different Measurement Techniques for Assessing Porous Structure of Food Products Dehydrated by Several Technologies. J. Food Eng. 2026, 402, 112688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Zhang, H.; Zeng, C.; Yuan, J.; Mu, Y.; Kang, S.; Wen, P. Effects of Drying Methods on Quality Characteristics and Flavor of Dried Apples. Sci. Technol. Food Ind. 2024, 45, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Jia, Y.; Li, Y.; Jiao, X.; He, Y.; Wen, L.; Wang, Z. Comprehensive Impact of Pre-Treatment Methods on White Radish Quality, Water Migration, and Microstructure. Food Chem. X 2024, 24, 101991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dermesonlouoglou, E.; Seretis, G.; Katsouli, M.; Katsimichas, A.; Taoukis, P.; Giannakourou, M. Effect of Pulsed Electric Fields and Osmotic Dehydration on the Quality of Modified-Atmosphere-Packaged Fresh-Cut and Fried Potatoes. Foods 2025, 14, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elimelech, E.; Ert, E.; Parag, Y.; Hochman, G. Exploring the Impact of Visual Perception and Taste Experience on Consumers’ Acceptance of Suboptimal Fresh Produce. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muniz, V.R.G.d.F.; Ribeiro, I.S.; Beckmam, K.R.L.; de Godoy, R.C.B. The Impact of Color on Food Choice. Braz. J. Food Technol. 2023, 26, e2022088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, C. On the Psychological Impact of Food Colour. Flavour 2015, 4, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, M.S.K.; Zhang, J.; Chan, K. Impact of Snack Packaging Colour on Perceptions of Healthiness and Tastiness. Asian J. Bus. Res. 2025, 15, 102–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Nian, R.; Li, Q.; Zhu, D.; Cao, X. Effects of Ultrasonic Pretreatment on Drying Characteristics and Water Migration Characteristics of Freeze-Dried Strawberry. Food Chem. 2024, 450, 139287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiktor, A.; Witrowa-Rajchert, D. Drying Kinetics and Quality of Carrots Subjected to Microwave-Assisted Drying Preceded by Combined Pulsed Electric Field and Ultrasound Treatment. Dry. Technol. 2020, 38, 176–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Yu, J.; Huang, D.; Chen, Y.; Fu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Jia, G. The Effect of Ultrasonic Pretreatment on the Drying Kinetics of Orange Peels under Different Drying Methods. Ind. Crops Prod. 2025, 233, 121479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbaspour-Gilandeh, Y.; Kaveh, M.; Zadhossein, S.; Gheisary, B.; El-Mesery, H.S. Application of Ultrasound Treatment in Cantaloupe Infrared Drying Process: Effects on Moisture Migration and Microstructure. J. Food Sci. 2025, 90, e70156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mari, A.; Parisouli, D.N.; Krokida, M. Exploring Osmotic Dehydration for Food Preservation: Methods, Modelling, and Modern Applications. Foods 2024, 13, 2783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Wang, X.; Li, D.; Liu, C.; Yang, Q.; Zhang, M. Effect of Starch Osmo-Coating on Carotenoids, Colour and Microstructure of Dehydrated Pumpkin Slices. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 55, 3249–3256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caparino, O.A.; Sablani, S.S.; Tang, J.; Syamaladevi, R.M.; Nindo, C.I. Water Sorption, Glass Transition, and Microstructures of Refractance Window- and Freeze-Dried Mango (Philippine “Carabao” Var.) Powder. Dry. Technol. 2013, 31, 1969–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joardder, M.U.H.; Bosunia, M.H.; Hasan, M.M.; Ananno, A.A.; Karim, A. Significance of Glass Transition Temperature of Food Material in Selecting Drying Condition: An In-Depth Analysis. Food Rev. Int. 2024, 40, 952–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haneef, N.; Hanif, N.; Hanif, T.; Raghavan, V.; Garièpy, Y.; Wang, J. Food Fortification Potential of Osmotic Dehydration and the Impact of Osmo-Combined Techniques on Bioactive Component Saturation in Fruits and Vegetables. Braz. J. Food Technol. 2024, 27, e2023028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiamba, I.; Ahrné, L.; Khan, M.A.M.; Svanberg, U. Retention of β-Carotene and Vitamin C in Dried Mango Osmotically Pretreated with Osmotic Solutions Containing Calcium or Ascorbic Acid. Food Bioprod. Process. 2016, 98, 320–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, S.; Tareq, A.M.; Das, R.; Bin Emran, T.; Nainu, F.; Chakraborty, A.J.; Ahmad, I.; Tallei, T.E.; Idris, A.M.; Simal-Gandara, J. Polyphenols: A First Evidence in the Synergism and Bioactivities. Food Rev. Int. 2023, 39, 4419–4441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parveen, B.; Rajinikanth, V.; Narayanan, M. Natural Plant Antioxidants for Food Preservation and Emerging Trends in Nutraceutical Applications. Discov. Appl. Sci. 2025, 7, 845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, B.; Li, Y.; He, X.; Sun, J.; Choe, U.; Chen, P.; Blaustein, R.A.; et al. Chemical Composition of Turmeric (Curcuma longa L.) Ethanol Extract and Its Antimicrobial Activities and Free Radical Scavenging Capacities. Foods 2024, 13, 1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quirós-Fallas, M.I.; Vargas-Huertas, F.; Quesada-Mora, S.; Azofeifa-Cordero, G.; Wilhelm-Romero, K.; Vásquez-Castro, F.; Alvarado-Corella, D.; Sánchez-Kopper, A.; Navarro-Hoyos, M. Polyphenolic HRMS Characterization, Contents and Antioxidant Activity of Curcuma longa Rhizomes from Costa Rica. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi-Rad, J.; El Rayess, Y.; Rizk, A.A.; Sadaka, C.; Zgheib, R.; Zam, W.; Sestito, S.; Rapposelli, S.; Neffe-Skocińska, K.; Zielińska, D.; et al. Turmeric and Its Major Compound Curcumin on Health: Bioactive Effects and Safety Profiles for Food, Pharmaceutical, Biotechnological and Medicinal Applications. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 01021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanvir, E.M.; Hossen, M.S.; Hossain, M.F.; Afroz, R.; Gan, S.H.; Khalil, M.I.; Karim, N. Antioxidant Properties of Popular Turmeric (Curcuma longa) Varieties from Bangladesh. J. Food Qual. 2017, 2017, 8471785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejias, N.; Vega-Galvez, A.; Pasten, A.; Uribe, E.; Andrés, A.; Muñoz-Pina, S.; Khvostenko, K.; García-Segovia, P. Evaluating the Microstructure and Bioaccessibility of Bioactive Compounds and Antioxidant Activity After the Dehydration of Red Cabbage. Foods 2025, 14, 1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Code | Pretreatment | Methodology |

|---|---|---|

| CTRL | Control | No pretreatment |

| SB | Steam blanching | Steam exposure for 1 min |

| MVB | Microwave blanching | Microwave treatment at 600 W, 1 min |

| PEFT | Pulsed electric field treatment | 2 kJ specific energy input |

| UST | Ultrasound treatment | 24 kHz, 50% cycle, 100% amplitude, 3 min |

| ODI | Osmotic dehydration (inulin) | 30% inulin + 2% vitamin C, 30 min, 55 °C |

| ODT | Osmotic dehydration (trehalose) | 30% trehalose + 2% vitamin C, 30 min, 55 °C |

| TS | Turmeric starch coating | 80% turmeric powder 20% + tapioca starch |

| SPS | Sweet paprika starch coating | 80% sweet paprika powder + 20% tapioca starch |

| Sample | Water Activity | Moisture Content [%] | Shrinkage [%] | Density [g/cm3] | Hardness [N] | Breaking Work [mJ] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTRL | 0.246 ± 0.036 b | 6.06 ± 1.01 a | 45.4 ± 4.2 ef | 1.48 ± 0.03 ab | 8.8 ± 1.7 abc | 15.5 ± 3.2 b |

| SB | 0.249 ± 0.027 b | 6.27 ± 1.92 a | 49.2 ± 3.4 f | 1.48 ± 0.03 ab | 9.7 ± 2.1 bc | 17.0 ± 5.2 b |

| MVB | 0.194 ± 0.064 ab | 6.67 ± 1.57 ab | 44.1 ± 4.1 de | 1.50 ± 0.03 ab | 11.8 ± 3.1 cde | 13.3 ± 5.0 b |

| PEFT | 0.246 ± 0.032 b | 5.46 ± 0.43 a | 49.1 ± 2.2 f | 1.49 ± 0.04 ab | 15.1 ± 3.6 e | 24.4 ± 5.6 c |

| UST | 0.206 ± 0.077 ab | 6.82 ± 1.14 ab | 46.0 ± 3.1 ef | 1.54 ± 0.04 b | 12.4 ± 3.9 de | 17.7 ± 6.9 b |

| ODI | 0.141 ± 0.018 a | 9.86 ± 1.46 ab | 27.9 ± 3.7 a | 1.44 ± 0.02 abc | 8.1 ± 2.4 ab | 3.8 ± 2.3 a |

| ODT | 0.234 ± 0.047 ab | 10.87 ± 0.98 b | 41.4 ± 4.3 cd | 1.42 ± 0.02 ac | 22.2 ± 4.6 f | 33.1 ± 6.9 d |

| TS | 0.171 ± 0.040 ab | 6.31 ± 0.27 a | 38.2 ± 4.4 bc | 1.47 ± 0.01 ab | 5.5 ± 0.9 a | 4.8 ± 2.5 a |

| SPS | 0.199 ± 0.030 ab | 6.26 ± 0.22 a | 36.5 ± 3.7 b | 1.36 ± 0.02 a | 5.3 ± 1.0 a | 4.8 ± 1.9 a |

| Sample | L* | a* | b* | C* | ΔE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RAW | 64.1 ± 3.5 b | −0.8 ± 0.1 a | 1.8 ± 0.6 a | 1.8 ± 0.7 b | - |

| CTRL | 71.0 ± 6.6 a | −1.6 ± 0.3 ab | 12.1 ± 2.3 c | 12.2 ± 2.3 a | 13.6 ± 4.1 c |

| SB | 71.1 ± 6.0 a | −1.8 ± 0.4 ab | 12.8 ± 2.6 cd | 12.9 ± 2.5 a | 14.0 ± 4.0 c |

| MVB | 73.3 ± 5.4 a | −1.9 ± 0.6 ab | 13.9 ± 3.4 cde | 14.1 ± 3.3 a | 15.9 ± 4.5 c |

| PEFT | 70.8 ± 5.7 a | −2.1 ± 0.3 b | 12.7 ± 2.5 cd | 12.9 ± 2.5 a | 13.7 ± 4.0 c |

| UST | 73.1 ± 7.5 a | −0.8 ± 1.4 ab | 15.6 ± 4.8 de | 12.2 ± 4.2 a | 18.3 ± 3.7 c |

| ODI | 70.1 ± 6.6 a | −1.1 ± 0.4 ab | 9.1 ± 2.1 b | 7.5 ± 2.7 c | 11.1 ± 3.8 a |

| ODT | 73.1 ± 6.9 a | −0.5 ± 1.0 a | 15.8 ± 3.6 e | 12.8 ± 5.0 a | 17.8 ± 4.5 c |

| TS | 60.2 ± 4.4 b | 14.3 ± 3.0 c | 65.9 ± 3.3 g | 67.5 ± 3.1 e | 66.1 ± 2.9 d |

| SPS | 43.6 ± 4.2 c | 23.9 ± 3.6 d | 35.7 ± 2.6 f | 43.0 ± 3.2 d | 46.9 ± 2.3 b |

| Sample | Dried Slice | Surface Microstructure/Cross-Section Microstructure | Internal Structure (µ-CT) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 200x | 1000× | 2000× | |||

| 100 µm | 20 µm | 10 µm | |||

| CTRL |  |  |  |  |  |

| SB |  |  |  |  |  |

| MVB |  |  |  |  |  |

| PEFT |  |  |  |  |  |

| UST |  |  |  |  |  |

| ODI |  |  |  |  |  |

| ODT |  |  |  |  |  |

| TS |  |  |  |  |  |

| SPS |  |  |  |  |  |

| Samples | Object Surface/ Volume Ratio (OSVR) [1/mm] | Structure Model Index (SMI) | Total Porosity [%] | Degree of Anisotropy (DA) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTRL | 45.5 ± 2.1 ab | 1.48 ± 0.35 a | 3.7 ± 3.5 a | 3.24 ± 0.85 a |

| SB | 37.0 ± 4.8 a | 1.1 ± 1.0 a | 3.1 ± 3.5 a | 35.50 ± 0.22 b |

| MVB | 38.0 ± 8.8 a | 2.08 ± 0.06 a | 0.41 ± 0.39 a | 16 ± 13 ab |

| PEFT | 39.0 ± 4.0 ab | 0.85 ± 0.28 a | 6.6 ± 6.0 a | 27 ± 26 ab |

| UST | 53 ± 28 ab | 1.72 ± 0.48 a | 5.40 ± 0.14 a | 23 ± 10 ab |

| ODI | 48 ± 19 ab | 1.20 ± 0.46 a | 6.4 ± 4.0 a | 6.6 ± 2.2 ab |

| ODT | 36.2 ± 4.2 a | 1.93 ± 0.31 a | 3.41 ± 0.24 a | 10.6 ± 3.9 ab |

| TS | 63 ± 28 ab | 1.64 ± 0.21 a | 23 ± 24 ab | 6.6 ± 2.7 ab |

| SPS | 97 ± 31 b | 1.65 ± 0.55 a | 57 ± 24 b | 8.6 ± 9.5 ab |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chobot, M.; Kozłowska, M.; Marzec, A.; Kowalska, H. The Effect of Pretreatments and Infrared Drying on the Quality of White Radish Slices. Foods 2026, 15, 423. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15030423

Chobot M, Kozłowska M, Marzec A, Kowalska H. The Effect of Pretreatments and Infrared Drying on the Quality of White Radish Slices. Foods. 2026; 15(3):423. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15030423

Chicago/Turabian StyleChobot, Małgorzata, Mariola Kozłowska, Agata Marzec, and Hanna Kowalska. 2026. "The Effect of Pretreatments and Infrared Drying on the Quality of White Radish Slices" Foods 15, no. 3: 423. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15030423

APA StyleChobot, M., Kozłowska, M., Marzec, A., & Kowalska, H. (2026). The Effect of Pretreatments and Infrared Drying on the Quality of White Radish Slices. Foods, 15(3), 423. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15030423