Echinacea Purpurea Polysaccharides Alleviate DSS-Induced Colitis in Rats by Regulating Gut Microbiota and Short-Chain Fatty Acid Metabolism

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material, Chemicals, and Regents

2.2. Experimental Animals

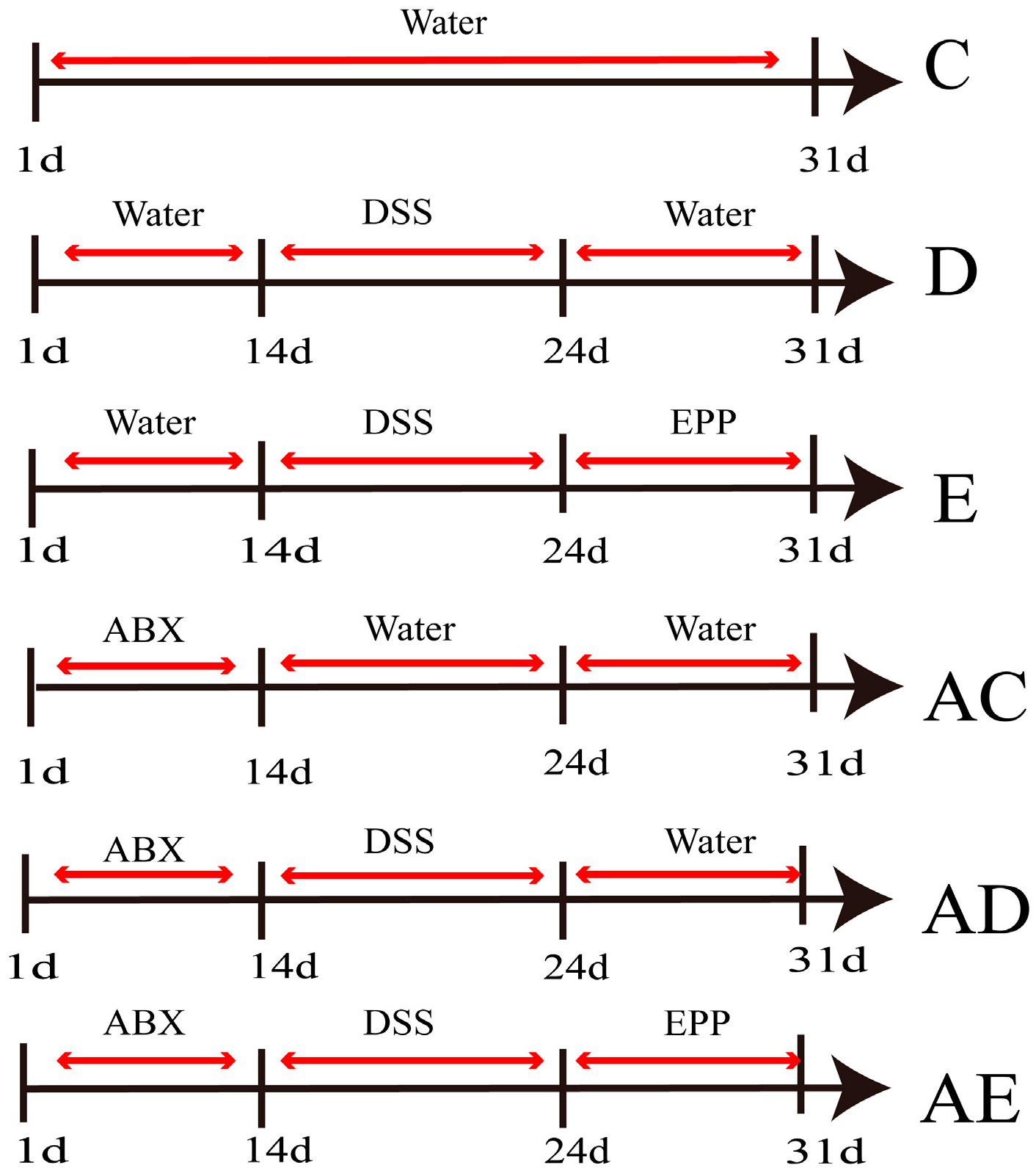

2.3. Establishment of ABX-DSS-Induced Rat IBD Model

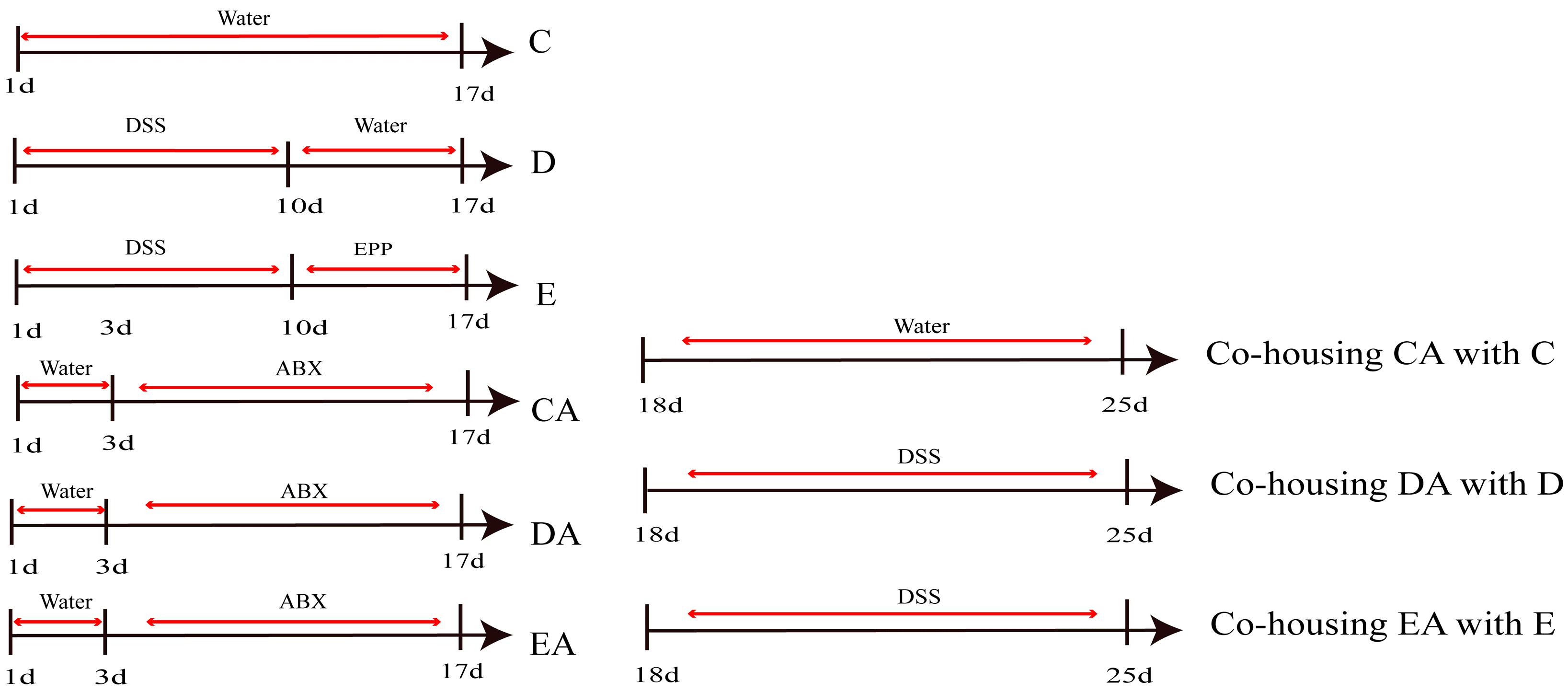

2.4. Establishment of Co-Culture Model and Group-Housing

2.5. Disease Activity Index

2.6. Histological Analysis

2.7. ELISA Test for IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1β in Serum

2.8. RT-qPCR Analysis

2.9. Western Blot Analysis

2.10. Gut Microbiota Analysis

2.11. Measurement of SCFAs in the Colon

2.12. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

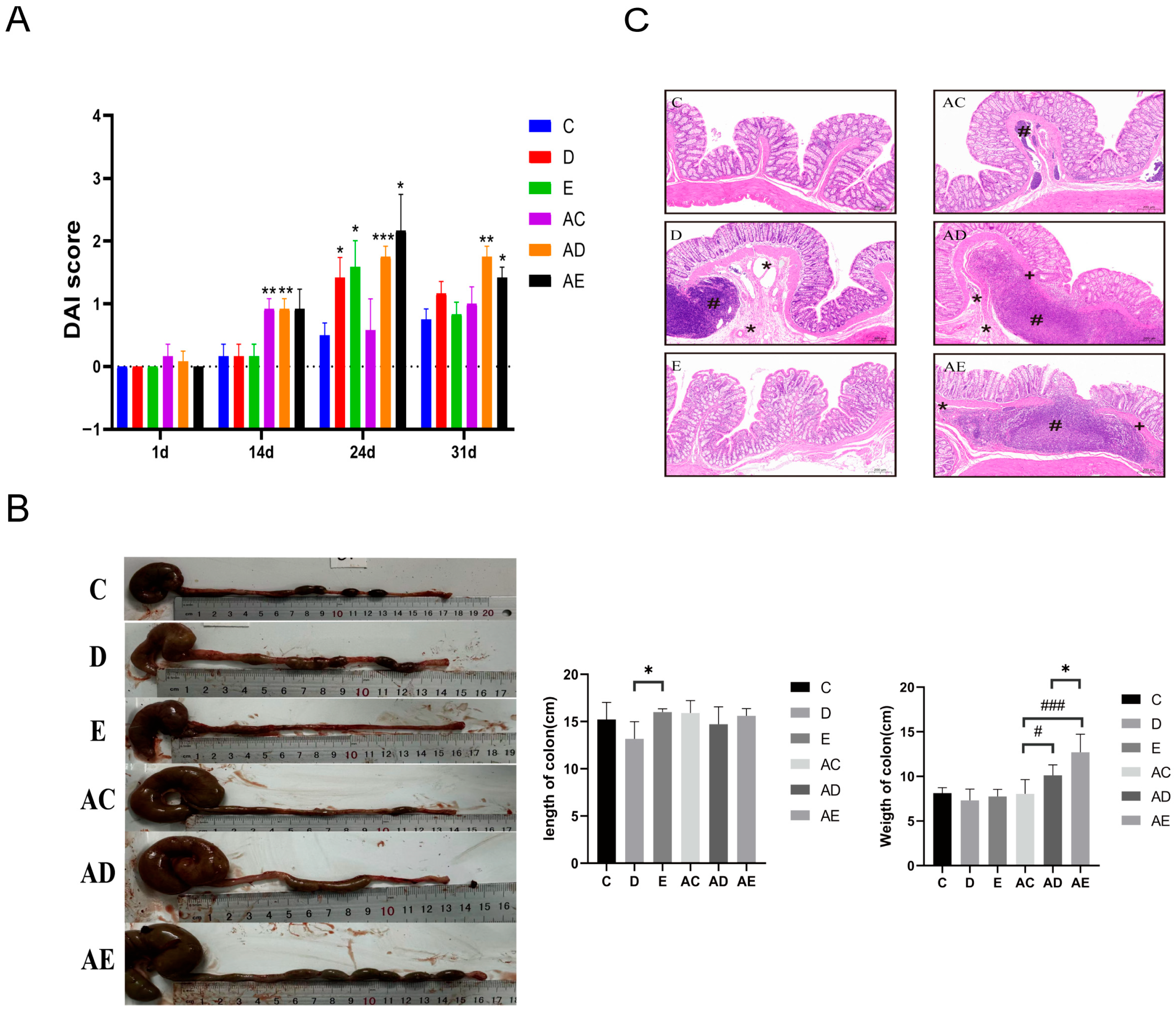

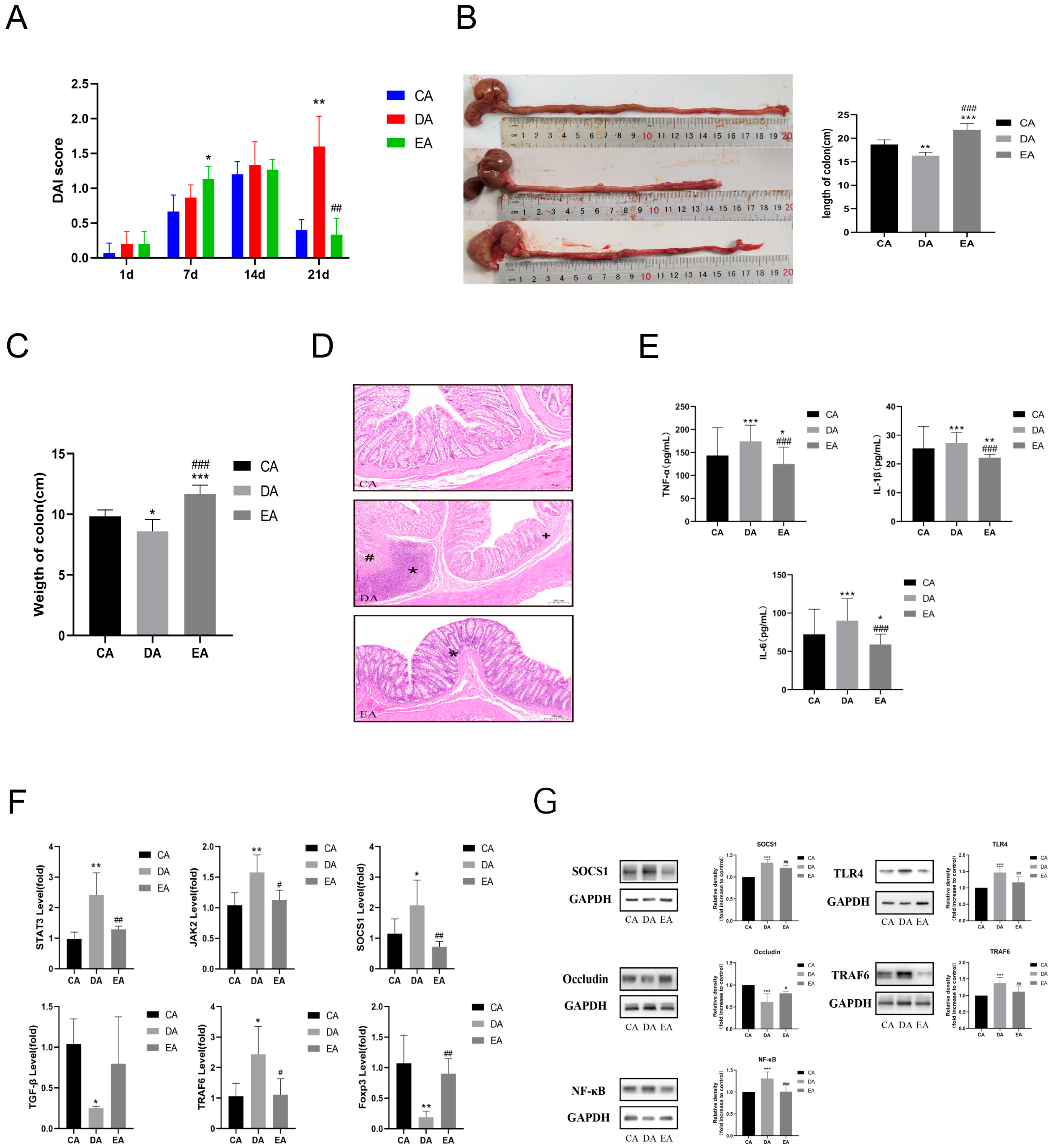

3.1. EPP Intervention Mitigated DSS-Induced Rat IBD

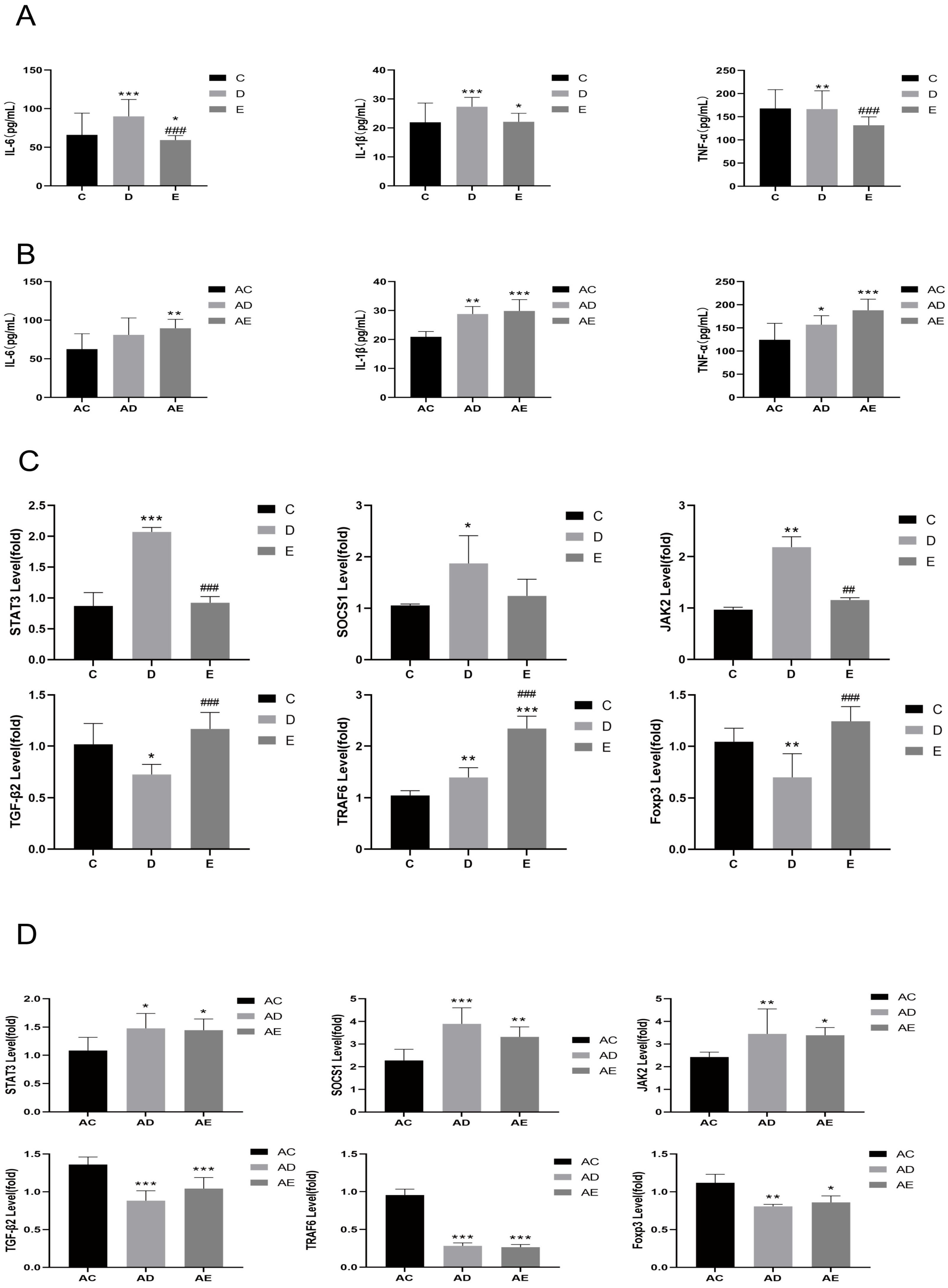

3.2. EPP Regulated Inflammatory Response

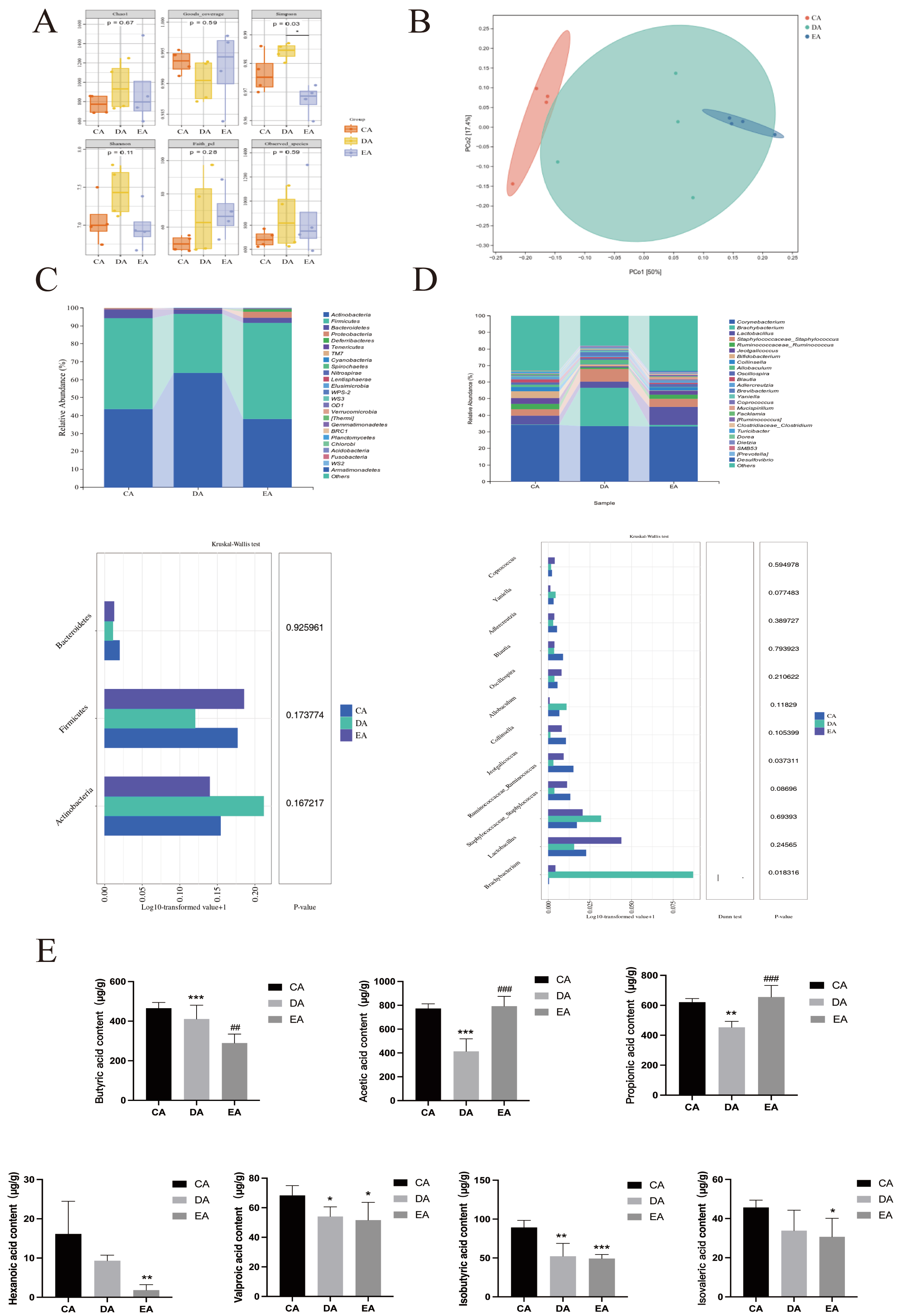

3.3. Transplantation of EPP-Altered Microbiota Recapitulated the Effects of EPP Treatment on DSS-Induced IBD

3.4. Changes in the Intestinal Microbiota of Co-Cultured Rats

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ABX | mixed antibiotic |

| IL-1β | interleukin-1β |

| IL-6 | interleukin-6 |

| DAI | Disease Activity Index |

| DSS | Dextran sulfate sodium |

| ELISA | enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| EPP | Echinacea purpurea polysaccharides disease |

| FMT | fecal microbiota transplantation |

| IBD | Inflammatory bowel disease |

| SCFAs | Short-chain fatty acids |

| SD | Sprague-Dawley |

| TNF-α | tumor necrosis factor-α |

References

- Marsilio, S.; Pilla, R.; Sarawichitr, B.; Chow, B.; Hill, S.L.; Ackermann, M.R.; Estep, J.S.; Lidbury, J.A.; Steiner, J.M.; Suchodolski, J.S. Characterization of the fecal microbiome in cats with inflammatory bowel disease or alimentary small cell lymphoma. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 19208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.J.; Zhao, X.; Wang, L.Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Chen, H.A. Gas Therapy Strategy for Intestinal Flora Regulation and Colitis Treatment by Nanogel-Based Multistage NO Delivery Microcapsules. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, e2309972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Liao, S.; Lv, L.; Li, C.; Mei, Z. Intestinal immune imbalance is an alarm in the development of IBD. Mediat. Inflamm. 2023, 2023, 1073984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.Y.; Li, M.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, J. The role of gut microbiota dysbiosis in the occurrence and development of inflammatory bowel disease and its prevention and control strategies. Chin. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 56, 1175–1181. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, Y.; Yang, L.; Li, W.; Hu, Y.; Zhu, B.; Zhou, M.; Ye, Y.; Ding, Z.; Zhou, F. Tetrastigma hemsleyanum polysaccharides alleviate inflammatory bowel disease via the gut microbiota-SCFA-GPR43 signaling axis. Phytomedicine 2025, 149, 157523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.T.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y. Gut microbiota in heart failure and related interventions. Imeta 2023, 2, e125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.H.W.; Bäckhed, F.; Landmesser, U.; Hazen, S.L. Intestinal Microbiota in Cardiovascular Health and Disease: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2019, 73, 2089–2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Hierro, J.N.; Cueva, C.; Tamargo, A.; García-Conesa, M.T.; de Pascual-Teresa, S.; Santos-Buelga, C. In vitro colonic fermentation of saponin-rich extracts from quinoa, lentil, and fenugreek. Effect on sapogenins yield and human gut microbiota. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeyneb, H.; Pei, H.; Cao, X.; Wang, Y.; Win, Y.; Gong, L. In vitro study of the effect of quinoa and quinoa polysaccharides on human gut microbiota. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 9, 5735–5745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, R.; Zhou, D.; Wu, S.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, H. Health benefits and side effects of short-chain fatty acids. Foods 2022, 11, 2863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calatayud, M.; Van den Abbeele, P.; Ghyselinck, J.; Marzorati, M.; Rohs, E.; Birkett, A. Comparative Effect of 22 Dietary Sources of Fiber on Gut Microbiota of Healthy Humans in vitro. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 700571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, X.; Wang, H.G.; Zhang, M.N.; Zhang, M.H.; Wang, H.; Yang, X.Z. Fecal microbiota transplantation ameliorates experimental colitis via gut microbiota and T-cell modulation. World J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 27, 2834–2849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miroshina, T.; Poznyakovskiy, V. Echinacea purpurea as a medicinal plant: Characteristics, use as a biologically active component of feed additives and specialized foods (review). E3S Web Conf. 2023, 380, 1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adebimpe, O.C.; Dziadek, K.; Sadowska, U.; Skoczylas, J.; Kopeć, A.; Wojewódzka, M. Analytical Assessment of the Antioxidant Properties of the Coneflower (Echinacea purpurea L. Moench) Grown with Various Mulch Materials. Molecules 2024, 29, 971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, F.H.; Xie, W.Y.; Zhao, P.S.; Gao, W.; Gao, F. Echinacea purpurea Polysaccharide Ameliorates Dextran Sulfate Sodium-Induced Colitis by Restoring the Intestinal Microbiota and Inhibiting the TLR4-NF-κB Axis. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Lin, Y.; Zheng, X.; Zheng, X.; Yan, M.; Wang, H.; Liu, C. Echinacea purpurea (L.) Moench Polysaccharide Alleviates DSS-Induced Colitis in Rats by Restoring Th17/Treg Balance and Regulating Intestinal Flora. Foods 2023, 12, 4265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, G.; Xu, W.; Ma, W.; Yu, Q.; Zhu, H.; Liu, C.; Cheng, Y.; Guo, Y.; Qian, H. Echinacea purpurea polysaccharide intervene in hepatocellular carcinoma via modulation of gut microbiota to inhibit TLR4/NF-κB pathway. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 261, 129917. [Google Scholar]

- Xizhan, X.; Zezheng, G.; Fuquan, Y.; Ming, L.; Hong, Z.; Wei, W. Antidiabetic effects of Gegen Qinlian decoction via the gut microbiota are attributable to its key ingredient berberine. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 2020, 18, 721–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, L.; Chen, K.; Chen, Z.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, L. Abelmoschi corolla polysaccharides and related metabolite ameliorates colitis via modulating gut microbiota and regulating the fxr/stat3 signaling pathway. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 277, 134370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Huo, Y.; Gao, X.; Li, M.; Zhang, H.; Liu, J. Lead exposure exacerbates liver injury in high-fat diet-fed mice by disrupting the gut microbiota and related metabolites. Food Funct. 2024, 15, 3060–3075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, J.; Wu, G.D.; Albenberg, L.; Tomov, V.T. Gut microbiota and IBD: Causation or correlation? Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 14, 573–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivière, A.; Selak, M.; Lantin, D.; Leroy, F.; De Vuyst, L. Bifidobacteria and Butyrate-Producing Colon Bacteria: Importance and Strategies for Their Stimulation in the Human Gut. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.X.; Guo, K.E.; Huang, J.Q.; Li, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhang, J. Curcumin alleviated dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis by recovering memory Th/Tfh subset balance. Phytomedicine 2024, 123, 154892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavelle, A.; Sokol, H. Gut microbiota-derived metabolites as key actors in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 17, 223–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rios-Covian, D.; González, S.; Nogacka, A.M.; Margolles, A.; de los Reyes-Gavilán, C.G.; Gueimonde, M. An overview on fecal branched short-chain fatty acids along human life and as related with body mass index: Associated dietary and anthropometric factors. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Zheng, N.; Davis, B.; Zhu, W.; Meng, D.; Walker, W.A. Short-chain fatty acid butyrate, a breast milk metabolite, enhances immature intestinal barrier function genes in response to inflammation in vitro and in vivo. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2021, 320, G521–G530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalile, B.; Van Oudenhove, L.; Vervliet, B.; Verbeke, K. The role of short-chain fatty acids in microbiota-gut-brain communication. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019, 16, 461–478. [Google Scholar]

- Rice, T.A.; Bielecka, A.A.; Nguyen, M.T.; Rosen, C.E.; Song, D.; Sonnert, N.D.; Yang, Y.; Cao, Y.; Khetrapal, V.; Catanzaro, J.R.; et al. Interspecies commensal interactions have nonlinear impacts on host immunity. Cell Host Microbe 2022, 30, 988–1002. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Wang, J.; He, T.; Becker, S.; Zhang, G.; Li, D.; Ma, X. Butyrate: A Double-Edged Sword for Health? Adv. Nutr. 2018, 9, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Y.; Chen, J. Staphylococcus aureus exacerbates DSS-induced colitis by disrupting intestinal barrier function. J. Med. Microbiol. 2023, 72, 001789. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Li, H.; Gong, T.; Chen, W.; Mao, S.; Kong, Y.; Yu, J.; Sun, J. Anti-neuroinflammatory Effect of Short-Chain Fatty Acid Acetate against Alzheimer’s Disease via Upregulating GPR41 and Inhibiting ERK/JNK/NF-κB. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2020, 68, 7152–7161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, B.; Yu, Y.; Wang, M.; Li, J.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Y. Targeting the jak2/stat3 signaling pathway with natural plants and phytochemical ingredients: A novel therapeutic method for combatting cardiovascular diseases. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 172, 116313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Pan, Y.; Shao, W.; Wang, C.; Wang, R.; He, Y.; Zhang, M.; Wang, Y.; Li, T.; Wang, Z.; et al. Beneficial effect of the short-chain fatty acid propionate on vascular calcification through intestinal microbiota remodelling. Microbiome 2022, 10, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Liu, C.; Lin, Y.; Du, X.; Mei, J.; Xi, K.; Gao, Y.; Li, Y.; Zuo, Z. Echinacea Purpurea Polysaccharides Alleviate DSS-Induced Colitis in Rats by Regulating Gut Microbiota and Short-Chain Fatty Acid Metabolism. Foods 2026, 15, 420. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15030420

Liu C, Lin Y, Du X, Mei J, Xi K, Gao Y, Li Y, Zuo Z. Echinacea Purpurea Polysaccharides Alleviate DSS-Induced Colitis in Rats by Regulating Gut Microbiota and Short-Chain Fatty Acid Metabolism. Foods. 2026; 15(3):420. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15030420

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Cui, Yongshi Lin, Xiaoxiao Du, Jiahui Mei, Kailun Xi, Yun Gao, Yuqing Li, and Zongtao Zuo. 2026. "Echinacea Purpurea Polysaccharides Alleviate DSS-Induced Colitis in Rats by Regulating Gut Microbiota and Short-Chain Fatty Acid Metabolism" Foods 15, no. 3: 420. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15030420

APA StyleLiu, C., Lin, Y., Du, X., Mei, J., Xi, K., Gao, Y., Li, Y., & Zuo, Z. (2026). Echinacea Purpurea Polysaccharides Alleviate DSS-Induced Colitis in Rats by Regulating Gut Microbiota and Short-Chain Fatty Acid Metabolism. Foods, 15(3), 420. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15030420