1. Introduction

In recent times, the world has been facing multiple crises that unequivocally affect food production. Climate change, pandemics, and geopolitical conflicts, as well as the rapid increase in population, have led to an imbalance between supply and demand, and a disruption of national and international food supply chains has already started [

1,

2]. Specifically, the demand for new nutritious food sources is rising, especially those that are vegetable-based, due to the extremely negative impact that the livestock industry has on global warming and environmental pollution [

3]. Among these foods, legumes, edible insects, macroalgae, and cultured meat are being assessed as the most reasonable alternatives to meat, because of their smaller environmental impact and valuable nutritional and health benefits [

4,

5]. Legumes have historically been consumed by humans, with evidence from various regions indicating their inclusion in early human diets approximately 12,000 years ago [

6]. Nonetheless, their consumption has surged in recent years due to their sustainability compared to animal protein sources.

Among legumes, lupins (

Lupinus spp.) emerge as major players in vegetable-based food research, due to their great nutritional value and high protein content, even higher than the largely used soybeans. In fact, despite varying between species and cultivars, crude protein in lupin account for 31 to 52% of dry matter, with exceptionally high concentrations of lysine, leucine, and phenylalanine [

7]. The

Lupinus genus includes more than 400 species, of which

L. albus (white lupin),

L. angustifolius (blue lupin),

L. luteus (yellow lupin), and

L. mutabilis (Andean lupin) are the most cultivated. In spite of the high yield, lupin cultivation areas and application remain relatively small, due to the lack of studies on crop practices [

8].

Despite their potential, lupin also represents a concern for human health due to the presence of antinutritional factors and its external contamination risks. One of the most important issues is linked to the presence of quinolizidine alkaloids (Qas). Qas are cyclic, nitrogen-containing secondary metabolites of the lupin plant that can cause poisoning in humans by affecting cardiovascular and nervous systems [

9]. Secondly, numerous studies have shown that lupins are highly susceptible to the presence of phomopsin A (PHO-A), a mycotoxin characterized by a cyclic hexapeptide structure produced by the fungus

Diaporthe toxica (anamorph

Phomopsis leptostromiformis) that has lupin as the main host. PHO-A is responsible for severe toxicity in numerous animal species. This suggests a possible risk also for human exposure [

10]. Therefore, to ensure the safe use of lupin beans and expand their food applications, it is crucial to develop approaches that effectively mitigate both these classes of undesirable compounds.

Currently, the reduction in Qas concentration in lupins intended for human consumption involves a post-harvest processing procedure known as ‘debittering’. Lupin seeds are first immersed in water for 24 h to facilitate moisture absorption. Thereafter, the rehydrated seeds are cooked at 95 °C for 25 min and then washed several times to promote alkaloid extraction through the exchange of substances between seeds and water. Throughout this procedure, a food-grade acid (e.g., lactic acid) is typically added to reach a pH below 4.5 that hinders microb”al g’owth. While this debittering process is currently the most common and effective method for removing alkaloids in the food industry, it requires large volumes of water and therefore causes unsustainable resource consumption and substantial economic losses.

Based on these challenges, alternative and more sustainable detoxification methods are deemed necessary. Ozone (O

3) is a strong oxidizing agent that has already attracted the attention of the scientific community for its preservation properties, as documented in prior studies, and recently garnered interest from the food industry as a potential method for food disinfection. In fact, it has demonstrated significant effectiveness against a wide range of microorganisms and mycotoxins affecting foods [

11]. Particularly, O

3 showed the ability to reduce aflatoxins up to 91%, as well as deoxynivalenol and ochratoxins even with less efficacy [

12]. In addition, O

3 rapidly auto-decomposes into molecular oxygen, leaving no residues neither in the treated food nor the environment, representing a “green” alternative to classical chemicals used for disinfection. Although its mechanisms of action are not completely clear yet, some studies hypothesized that it could react with functional groups in the cell membrane or in the mycotoxin chemical structure [

12,

13]. Moreover, recent studies demonstrated that O

3 treatments can exert a positive effect on ascorbic acid retention in vegetables and, consequently, have no impact on antioxidant potential of species such as lupin and cause only minor structural changes in protein and starch molecules [

14,

15]. Furthermore, O

3 showed notable results in reducing the levels of secondary metabolites across different vegetable species, including alkaloids, even though the published data remain very limited [

16].

To the best of our knowledge, no studies have yet examined the effectiveness of O3 treatments in lowering PHO-A or Qas. Therefore, this study aimed to develop and evaluate sustainable processing methods for enhancing the safety and quality of Lupinus albus beans. Specifically, the first aim was to investigate the effectiveness of aqueous and gaseous ozone treatments in reducing PHO-A content, by assessing various application methods and exposure times. Moreover, the study explored the efficacy of the same ozone treatments in reducing Qas levels.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fungal Strain

The fungal toxigenic strain Diaporthe toxica DSM 1894, anamorph Phomopsis leptostromiformis, was purchased from the Leibniz Institute (DSMZ-German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures GmbH, Braunshweig, Germany). In accordance with the institute’s recommendations, the strain was routinely cultivated on Oat Flake Medium (OFM), using the following preparation method: 30 g of dehydrated oat flakes were boiled under stirring in 500 mL of distilled water for 10 min; then, the volume was filled up to 1 L, and 20 g agar were added. Successively, the medium was sterilized at 121 °C for 20 min and shaken before pouring into sterile Petri dishes.

2.2. Lupin Samples Inoculation

Lupinus albus L. var. Multitalia beans from Southern Italy were kindly provided by Madama Oliva SpA. Lupins were artificially inoculated as optimized in previous studies [

17], according to the following procedure: dry lupin beans were sterilized at 121 °C for 15 min to prevent any potential contamination from naturally occurring microbial species. Then, lupin beans were immersed into sterile water at a 1:2

w/

v ratio under agitation for 30 min, to obtain a 0.98 ± 0.01 a

w, measured by an Aqualab 4TE hygrometer (METER Group, Inc., Pullman, WA, USA), which is one of the optimal conditions for fungal growth and mycotoxin production [

18]. Round mycelial plugs of 8 mm diameter were inoculated into the center of Water Agar (WA) Petri dishes. Then, 10 rehydrated lupins were distributed encircling the inoculum at 35 mm distance to ensure equal and simultaneous inoculation. Finally, the plates were incubated at 25 ± 1 °C to ensure an optimal growth of the fungus. The time when the hyphae reached the beans was considered the initial time point (t0) of the experiment; from t0, WA plates containing lupin beans were kept incubated at the same temperature for 168 h.

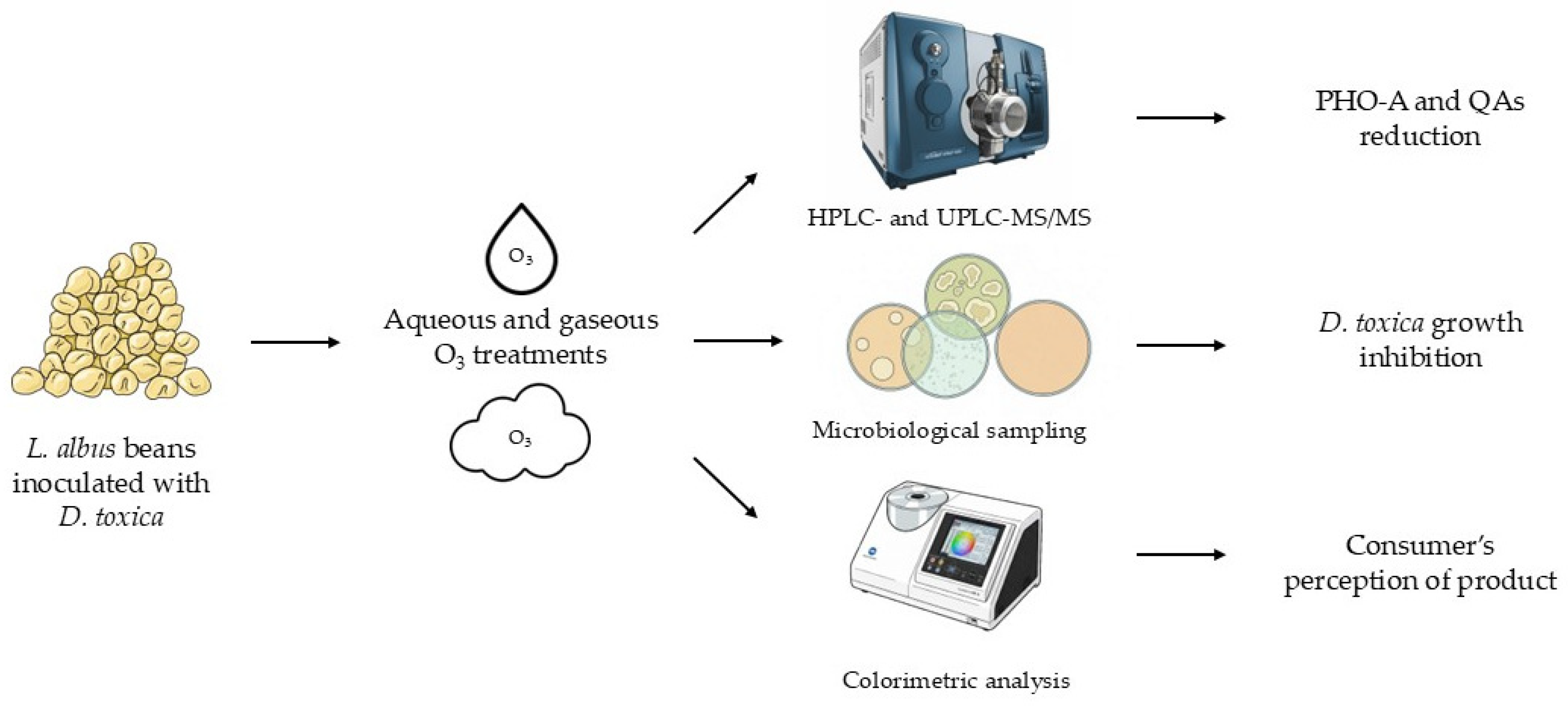

Following the incubation period, contaminated lupin beans were collected and analyzed for PHO-A and Qas concentration,

D. toxica counts, and color parameters, as detailed in

Figure 1.

2.3. Ozone Treatment

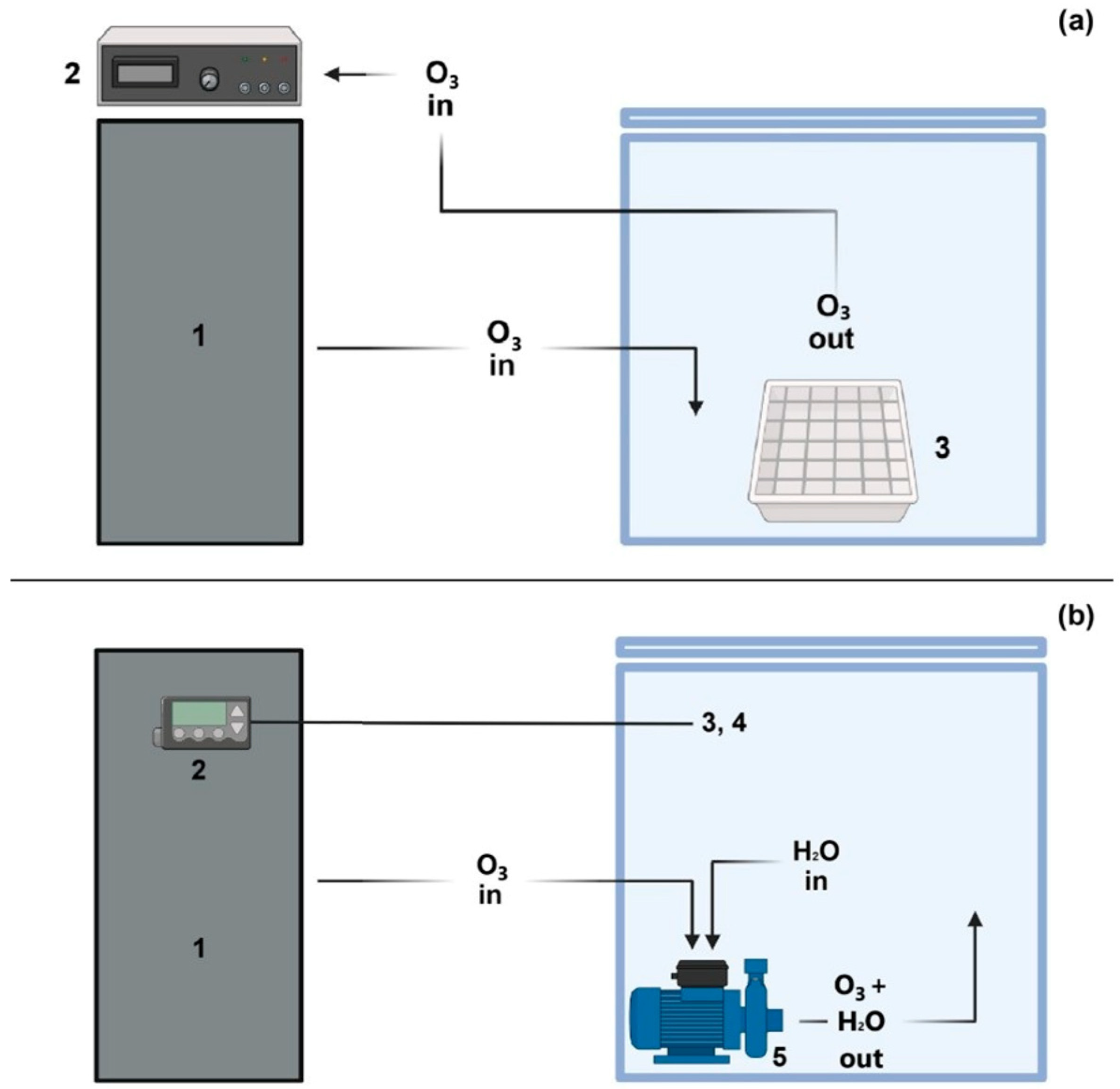

O3 treatments were performed both in water and in gaseous phases, using a 15 g/h O3 generator (Biofresh S.r.l., San Lazzaro di Savena, Bologna, Italy) equipped with an ozone analyser model UV-100 (Interlink Electronics, Inc., Camarillo, CA, USA) for gaseous treatment, and a programmable logic controller (PLC) (B&C Electronics S.r.l., Carnate, MB, Italy) for the aqueous treatment. These devices allowed a proportional, integrative, and derivative control of O3 generation, dispersed O3 concentration, and temperature by means of an electrode and a probe, respectively. O3 was generated in a self-assembled, cubical Plexiglas chamber of 65 cm edge dimension. For gaseous O3 treatment, the chamber was left empty, while for aqueous treatment it was filled with 100 L tap water.

One hundred inoculated lupin beans were prepared for each analysis. For the treatments with gaseous O

3, lupin beans were posed on a stainless-steel mesh stand, placed at the bottom of the chamber (

Figure 2), whereas the treatments with aqueous O

3 were performed by immersing lupin beans in water and maintaining them under agitation by means of a pump that was also used to dissolve O

3 in water in the chamber (

Figure 2).

After some preliminary trials at 1.5, 3.0, and 3.5 ppm O

3 concentration, performed according to the literature [

19], where neither PHO-A nor alkaloids concentration reduction was observed, the treated samples were subjected to a continuous O

3 flow at a concentration of 7.00 ± 0.01 ppm for alternatively 4, 6, or 8 h. The time of analysis was calculated from the stabilization of O

3 concentration in the chamber. For each treatment, a control (C) sample was considered. Control sample for gaseous ozone treatment was produced by leaving the same number of lupin beans in the chamber without O

3 for the same time of the treatment.

Instead, C samples for aqueous ozone treatment were obtained by immersing one hundred inoculated lupin beans under agitation into the corresponding water volume and time, with no O

3 dispersion. Temperature of the chamber was monitored by the PLC device and maintained always constant at 25.0 ± 0.1 °C. Tests were performed in triplicate. Samples and treatments are described in

Table 1.

2.4. PHO-A Quantification in Lupin Samples

The quantification of PHO-A was performed according to Eugelio et al. [

20], by the following method: 200 mg lupin samples, were milled with a domestic blender and reduced to a slurry immediately after O

3 treatment, and extracted with an 80:20 (

v/

v) CH

3CN/H

2O solution employing a Precellys Evolution homogenizer (Bertin Technologies, Montigny-Le-Bretonneux, France). The extracts were furtherly centrifuged at 11,424 rcf, and 500 µL supernatant was collected. The extraction solution was evaporated with a SpeedVac Concentrator (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), and the precipitate was resuspended into 500 µL H

2O with CF

3COOH 0.1%. The resulting samples were filtered through Amicon Ultra 0.5 Centrifugal Filters 3K devices (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) and further purified by µ-Solid Phase Extraction (SPE) clean-up. After extraction, PHO-A in lupin samples was determined by an ACQUITY UPLC H-Class System (Waters Corp., Milford, CT, USA) coupled to a 4500 Qtrap mass spectrometer (Sciex, Toronto, ON, Canada), equipped with an electrospray ionization (ESI) source. The chromatographic run was carried out by using an Excel 2 C18-PFP (100 × 2.1 mm) column from ACE (Aberdeen, UK), packed with 2 µm particles and equipped with a security guard column, while the mobile phases consisted of H

2O 5 mM HCOONH

4 (A) and ACN/MeOH 50:50 (

v/

v) with 0.1% HCOOH (B). The UHPLC-MS/MS method for PHO-A quantification on lupin samples was validated in accordance with the SANTE/11312/2021 guidelines for analytical quality control and method validation procedures for pesticide residues analysis in food and feed [

21], following the approach described by Eugelio et al. [

20]. Validation included the evaluation of linearity, carry-over, recovery, matrix effect, limits of detection (LOD), and quantification (LOQ), as well as accuracy and precision.

2.5. Qas Quantification in Lupin Samples

Lupanine, sparteine, multiflorine, and hydroxylupanine (OH-lupanine) in the samples were quantified by processing lupin beans according to Eugelio et al. [

9]. The samples were mechanically homogenized, and an aliquot of 200 mg was extracted with 1 mL MeOH/H

2O 60:40 (

v/

v) solution by Precellys Evolution homogenizer. Then, the samples were subjected to centrifugation at 11,424 rcf, and 50 µL supernatant were collected and diluted to 1 mL to obtain a final H

2O/MeOH ratio equal to 90:10 (

v/

v). This solution was purified by performing a clean-up with polymeric SPE cartridges. Analysis of QA was performed with an ACQUITY UPLC H-Class System (Waters Corp., Milford, MA, USA) coupled with a 4500 Qtrap mass spectrometer (Sciex, Toronto, ON, Canada), equipped with a heated ESI source. The analytes were separated using an Excel 2 C18-PFP (10 cm × 2.1 mm ID) column from ACE (Aberdeen, UK), packed with 2 µm particles and equipped with a security guard column. The mobile phases consisted of H

2O with 0.1% of heptafluorobutyric acid (HFBA) (C) and ACN/MeOH 50:50 (

v/

v) with 0.1% of HFBA (D). The UHPLC-MS/MS method for Qas quantification on lupin samples was validated according to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) guidelines [

22], following the procedure previously described by Eugelio et al. [

9]. The validation included the assessment of linearity, carry-over, recovery, matrix effect, LOD, LOQ, accuracy, and precision.

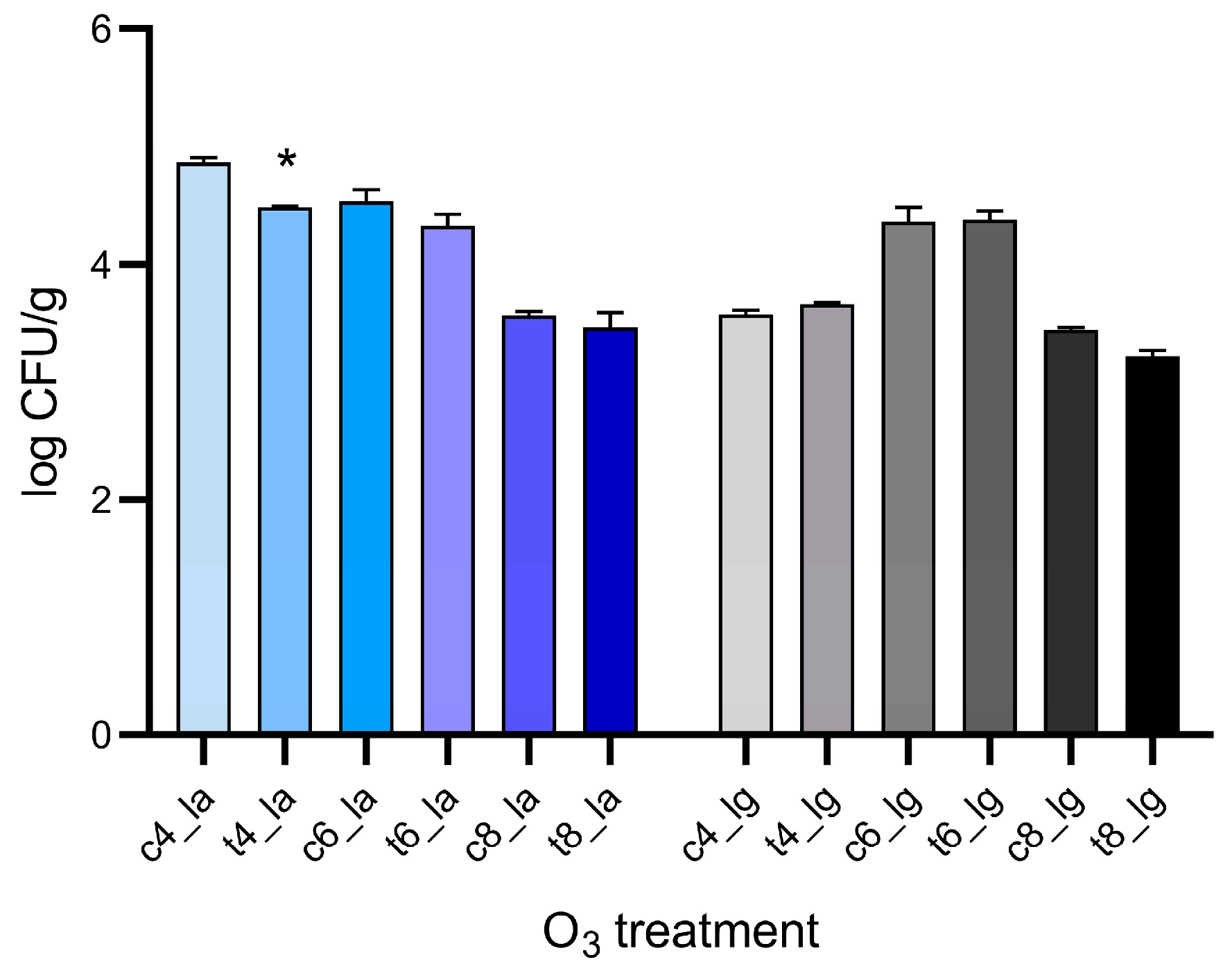

2.6. Microbiological Analysis

To evaluate the effect of O3 treatment on the D. toxica count on lupins, microbiological sampling was carried out as follows: 25 g inoculated lupin beans were homogenized at 1:10 ratio with physiological saline solution (0.90% NaCl) for 5 min at 230 rpm using a peristaltic homogenizer (Stomacher Lab Blender 400 Circulator, Seward, UK). The obtained suspension was serially diluted 1:10 and plated onto sterile Yeast, Peptone, Dextrose (YPD) agar plates. D. toxica counts were evaluated after 72 h incubation at 25 °C. A sterile culture medium was used as a blank control to confirm all operations were carried out in aseptic conditions. Tests were conducted in triplicate.

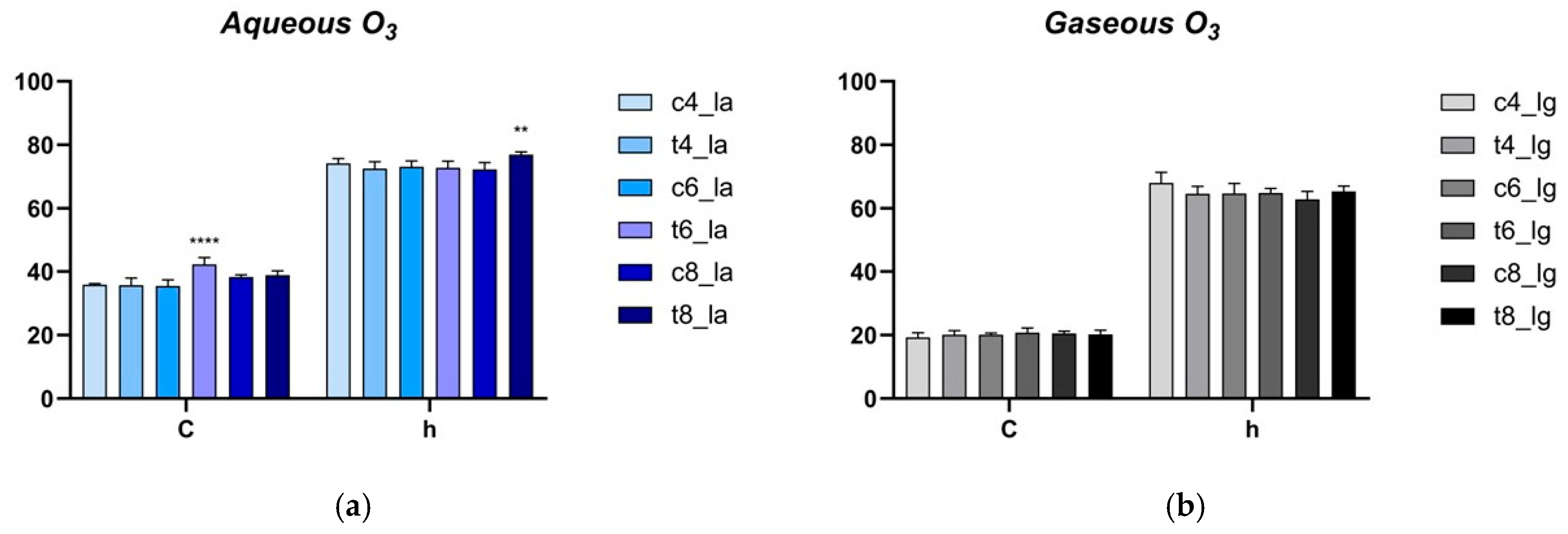

2.7. Color Determination of Lupin Samples

To analyze the effect of ozone on lupins, their color change has been evaluated as the most important sensory attribute of the product for consumer acceptance. Lupin beans color analysis was performed on uninoculated samples subjected to the same treatments of the inoculated ones, by recording CIELab color space coordinates L* (lightness), a* (redness), b* (yellowness), C (chroma), and h (hue angle), by means of a CR-5 colorimeter configured with D65 standard illuminant and 10° standard observer angle (Konica Minolta Sensing Europe, Tokyo, Japan), equipped with a CM-A195 3 mm diameter target mask (Konica Minolta Sensing Europe, Tokyo, Japan). These coordinates were selected to render lupin color in a uniform space before and after treatments and evaluate whether a numerical change in values could identify a perceived difference for the consumer. To this effort, the global color difference was calculated as follows: ΔE = ((

L*T −

L*C)

2 + (

a*T − a*

C)

2 + (

b*T −

b*C)

2)

1/2, and

a* and

b* values were used to calculate hue angle h° = arctan (

b*/

a*) and chroma C = (

a*2 +

b*2)

1/2 [

23]. Perceivable differences in color were classified according to Adekunte et al. [

24]. Values were acquired through reflectance measurements of samples. Reported values represent the values of 5 lupin beans from each sample. Five measurements were performed on different areas of each lupin bean.

2.8. Data Statistical Analysis

Software Analyst 1.7.2 and Multiquant 3.0.3 were used to collect and process data and quantify PHO-A and alkaloids in lupin samples, respectively. Statistical data analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 8.0.2 (GraphPad Software, Inc., Boston, MA, USA). t-tests, or analysis of variances followed by either Dunnett’s or Tukey’s tests (p < 0.05) were used to determine whether O3 treatment caused significant differences in PHO-A, Qas concentration, fungal counts and color parameters between each treatment and its corresponding control, and among different treatments.

4. Discussion

The safety of lupin-based foods is primarily compromised by fungal contamination (PHO-A) and endogenous toxic compounds (QAs) [

25]. Therefore, in this work, the efficacy of O

3 was evaluated against PHO-A, QAs, and mold growth, to explore possible strategies for reducing the associated risk.

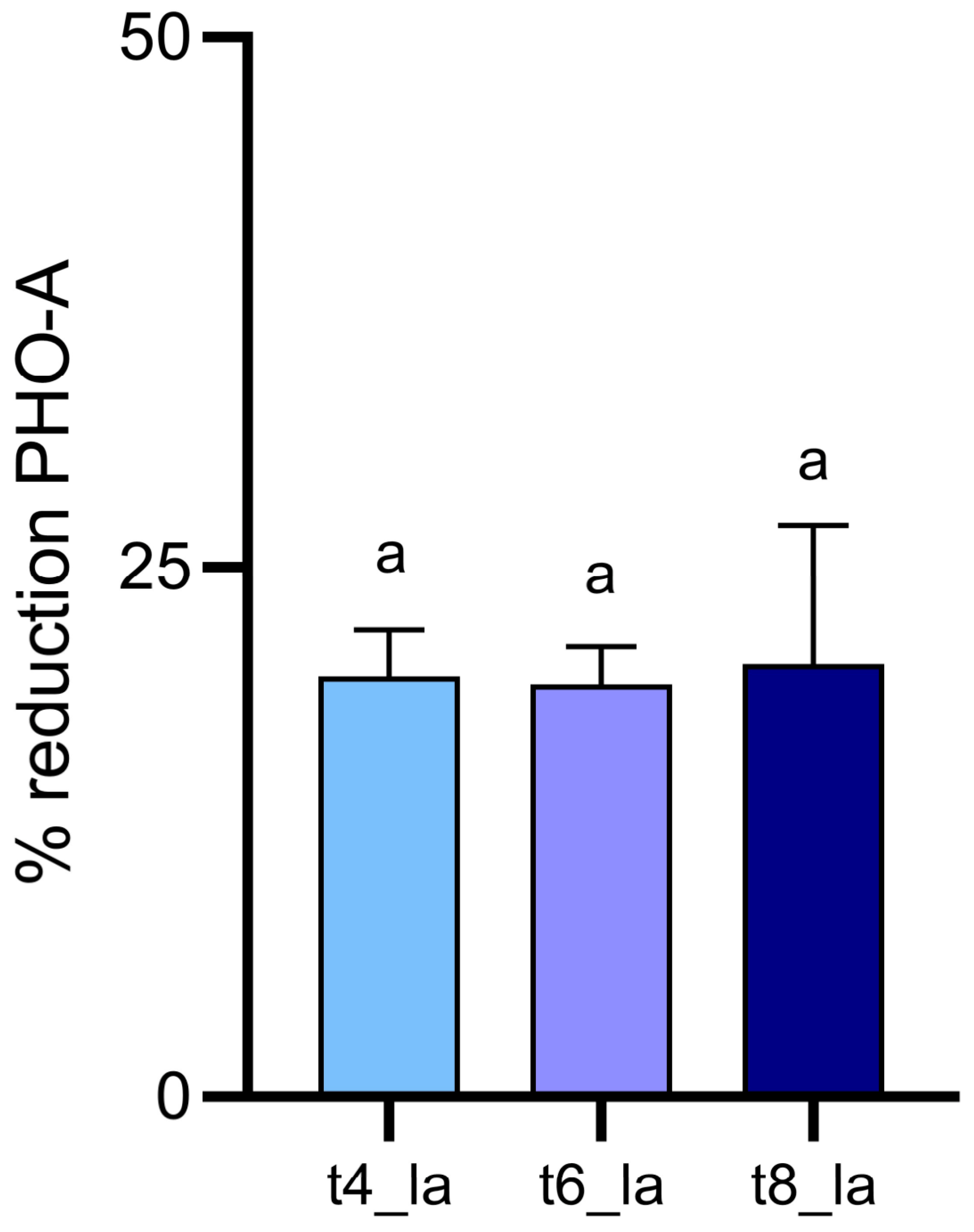

Concerning the effects of O

3 on PHO-A, the results obtained are noteworthy since the starting concentration was significantly higher than the LOD (1.0 ppm). Moreover, given the high chemical stability of PHO-A, a 20% reduction is a significant result, which can help decrease contamination levels. These results are only partially in agreement with published data. As evidenced by some authors, the efficacy of ozone as an anti-mycotoxin treatment does not necessarily increase by extending the treatment duration [

26]. Particularly, oxidation can be influenced by different factors, such as temperature, pH, and pressure, as well as the food matrix and the mycotoxin distribution [

13]. Although other studies have agreed on the idea that extended ozonation treatments can lead to increased reductions in mycotoxins content [

27], in our study the treatment efficacy was stable during time, probably because of the deep inoculation of

D. toxica and the consequent presence of PHO-A underneath the seeds surface. In fact, as shown for the aqueous ozonation [

28], the effectiveness of ozone is limited to the surface of the product. Based on our data, gaseous O

3 treatments did not have an efficacy against PHO-A. These results contradict numerous research in the literature that claim not only a greater efficacy of gaseous O

3 but also a stronger detoxifying activity compared to aqueous O

3 treatments [

29].

Some studies have confirmed the superior efficacy of aqueous O

3 against mycotoxins, especially where some gaseous O

3 yielded no appreciable results [

30,

31]. In this case, the aqueous medium may have acted as a more efficient carrier, facilitating deeper ozone penetration into lupins outer layers. Compared with the existing evidence concerning the detoxification of mycotoxins by ozone, these results suggest that this technology acts by directly degrading the mycotoxin through its oxidizing effects. The main mechanism proposed for mycotoxins inactivation by means of ozone is the reactivity against exposed unsaturated chemical bonds, and therefore the most susceptible molecules are Aflatoxins B1 and G1, and trichothecenes [

32]. Consequently, the observed result could be attributable to the higher resistance of PHO-A compared to other mycotoxins, and its different chemical structure, including its hexapeptide formation and modifications, which was frequently demonstrated as greatly stable even when subjected to strong detoxification treatments [

32,

33]. The observed significant reduction in PHO-A levels following ozone treatment represents a crucial result, especially considering the current lack of reported physical or chemical detoxification methods for this mycotoxin in the literature, that can help decrease the decontamination level below the regulatory threshold of 5 μg/kg. While O

3 efficacy is very promising, the complex nature of its reactions with organic molecules makes resulting chemical structures and biological activities difficult to identify. Nevertheless, the ability of O

3 demonstrated in PHO-A reduction makes it a valuable technology in ensuring lupin safety, evidencing the need for future studies elucidating PHO-A degradation pathways and assessing the reaction products safety for human health.

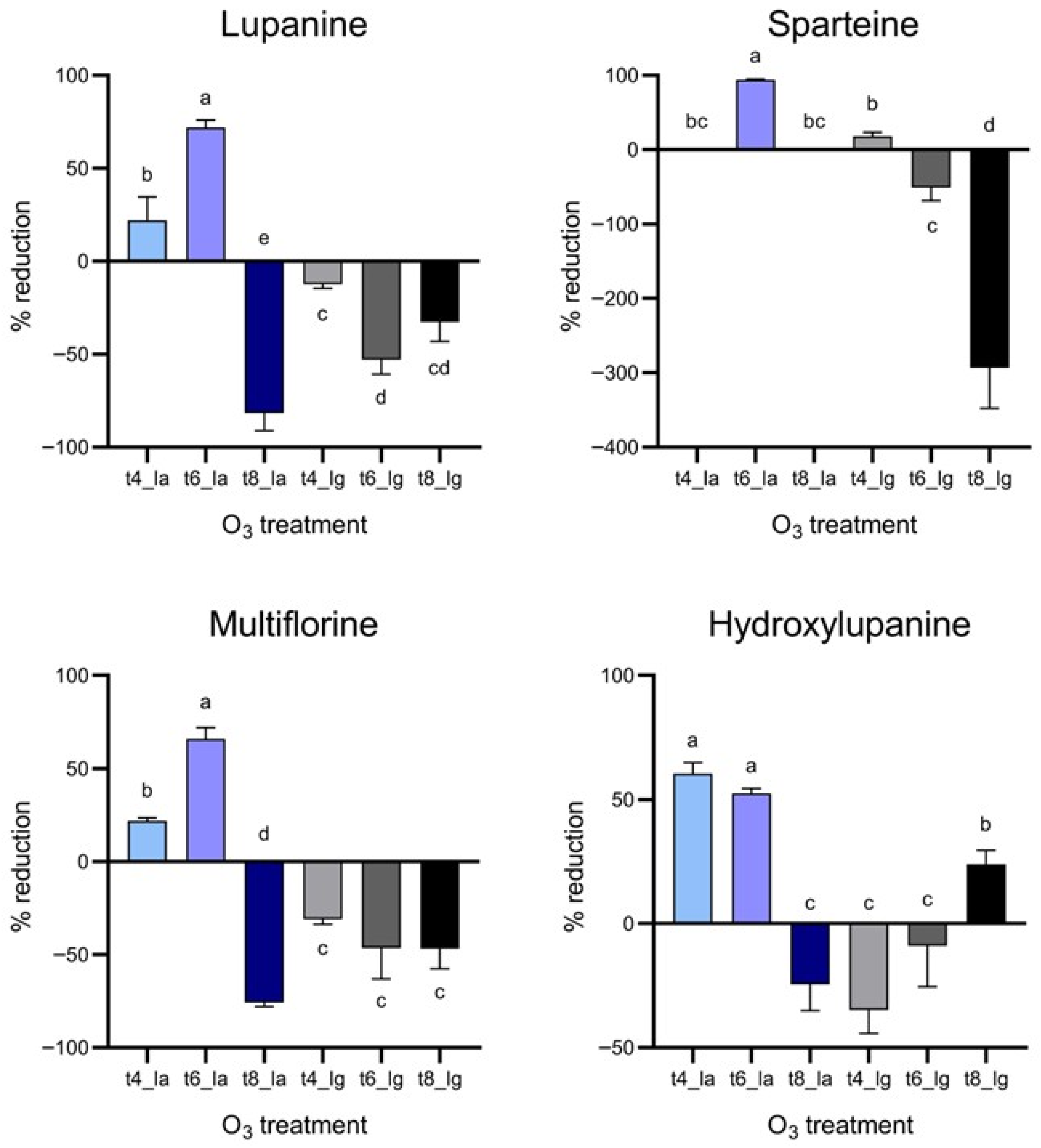

Considering the quantification of alkaloid species in lupin beans after O

3 treatment, the results strongly agree with many studies where a decrease in alkaloids was observed in various plant materials, even though no evidence has been reported on QA. For instance, ozone treatments resulted in a significant reduction in pyrrolizidine alkaloids in oregano and indole alkaloids in chickpea grains [

15,

16]. No results have been reported in the literature on lupin beans directly exposed to ozone treatments, even though it has been proved that elevated concentrations of ozone stress the plant, increasing the concentrations of secondary metabolites, including alkaloids, by regulating the polyamines in the alkaloid pathway [

34]. Moreover, because of the effect of ozone, it could not be excluded that other QA species, undergoing strong oxidation, could generate one of the species under investigation.

Similarly to what was described for PHO-A, while the reduction in QA levels can be considered a positive result, chemical structures and biological activities of their degradation products remain largely uncharacterized. In fact, O

3 reaction with complex organic molecules often leads to the formation of numerous intermediate products, which remain difficult to identify and may possess different toxicological properties than the original compounds. However, despite this potential issue, the efficacy demonstrated in alkaloid reduction makes O

3 a technology worth to be furtherly explored. Differently from the good potential shown by ozone in reducing PHO-A and QAs in lupin samples, microbiological investigations indicated that O

3 treatments resulted in relatively minimal reduction in fungal growth. In this respect, the scientific literature on the efficacy of O

3 on molds indicates that the effects can be inconsistent and frequently constrained due to several factors. Notably, while ozone can delay hyphae development and reduce sporulation, it does not consistently eradicate the infection, a condition that may elucidate the findings of the current study. Moreover, according to other authors, the effectiveness of O

3 exhibited a high variability depending on the fungal species: for instance, certain

Aspergillus species revealed different responses to treatments, with some displaying greater susceptibility than others [

35,

36]. Furthermore, many environmental conditions have been demonstrated to be potentially involved in O

3 effectiveness in fungal inactivation [

37].

PHO-A reduction was inconsistent with fungal inhibition. Thus, the observed 19.83, 19.44 and 20.40% reductions in PHO-A are highly due to a direct chemical degradation of the already formed toxin. In fact, PHO-A presents different disulphide bonds and unsaturated carbon-carbon bonds, as well as aromatic or heterocyclic structures, which are potential sites for oxidative attack by ozone [

38]. Consequently, further steps could include not only the evaluation of the fungal load after the incubation time, but also the influence of the treatment on mycelia growth and spore germination, and a screening of detoxification reaction intermediates. Finally, the color of the lupin beans was evaluated as a quality attribute after O

3 treatments to determine if these treatments might affect their appearance and, consequently, their acceptability to the consumer. Particularly, ΔE measurement demonstrated no perceivable differences in any of the samples undergone to gaseous treatments and in most of aqueous treatments. This stability is particularly noteworthy, given the strong oxidative potential of O

3. Therefore, the outcomes of this study demonstrate that the treatments targeted the contaminants (PHO-A and QAs) without inducing significant browning of the seeds. This behavior is quite common as previous studies evidenced the minimal impact of ozone treatments on the color attributes of legumes; particularly, no significant variations were observed on dried green beans or chickpeas [

15,

39]. Consequently, it can be argued that O

3 can be suitable for the potential industrial scale-up for treatments of legume seeds and seems to fit the detoxification of lupin beans.

5. Conclusions

This study aimed at evaluating the effectiveness of different ozone treatments on the main safety-related concern of lupin seeds, to upgrade their value both as ready-to-eat products, and as new plant-based protein sources.

The obtained results suggest an interesting activity of aqueous ozone that was able to produce a 19.83, 19.44, and 20.40% reduction in PHO-A concentration (

Figure 3). This result is noteworthy considering that this mycotoxin is particularly resistant to detoxification procedures. Simultaneously, a reduction in QA from 22.17% and up to 71.86% was observed after O

3 aqueous treatments. However, specific toxicological data on the ozone-induced degradation products of PHO-A and QAs in lupin beans are currently scarce. Therefore, a comprehensive assessment of the safety of ozone-treated lupin products for human consumption would ideally require the identification and subsequent toxicological evaluation of these specific by-products. Interestingly, the treatments minimally impacted the color properties of lupin seeds, demonstrating how ozone could be a suitable technology in lupin production process.

In addition, gaseous ozone treatments showed lower effectiveness although, in some cases, they demonstrated a potential that could be explained by further studies. In fact, most of the available literature agrees in attributing gaseous ozone a higher efficacy than aqueous ozonation.

Based on the results achieved, this study proposes an innovative solution to mitigate the risk associated with PHO-A and QA in lupin beans. Ozone can be applied directly in the industrial washing tanks, without major changes in the equipment. This solution also improves the effectiveness of the washing procedures. Considering the high stability of PHO-A, our results can be considered useful for mitigating the effect of PHO-A and QA compounds on health, although additional evaluation of the toxicity of these compounds after ozone treatments are recommended. Future research should also address the possible impact of ozone treatments on lupin nutrients and on the bioactive potential of this legume.