Changes in the Amino Acid Composition of Bee-Collected Pollen During 15 Months of Storage in Fresh-Frozen and Dried Forms

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Collection of Bee Pollen

2.2. Bee Pollen Preparation

2.2.1. Preparation of Dried Bee Pollen Samples

2.2.2. Preparation of Frozen Bee Pollen Samples

2.3. Chemicals

2.4. Preparation of Ethanol Extract from Bee Pollen

2.5. UHPLC-ESI-MS/MS Method for the Qualitative and Quantitative Analysis of Free Amino Acids

2.6. Application of the First-Order Degradation Model

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

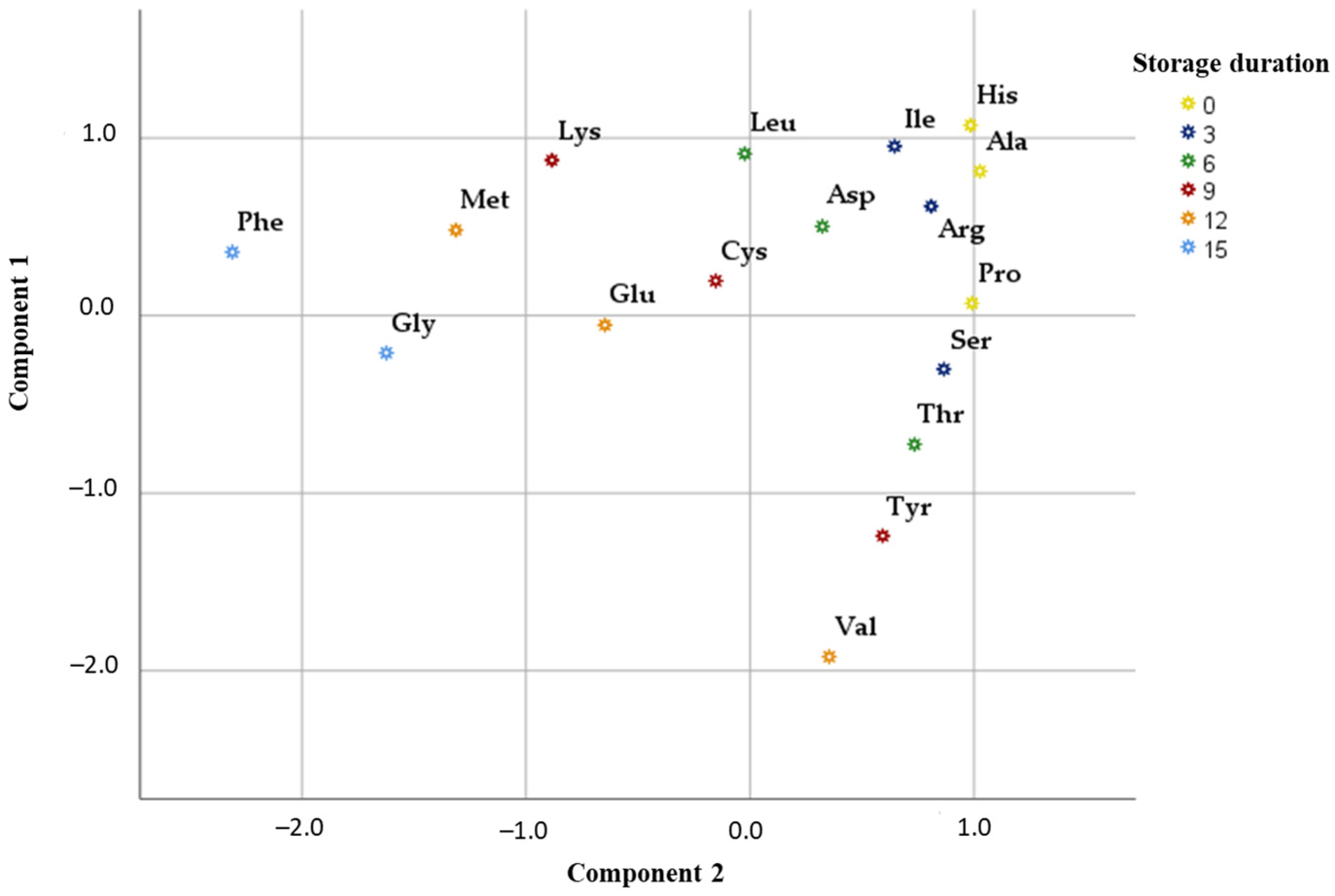

3.1. Qualitative and Quantitative Profiling of Free Amino Acids by UHPLC-ESI-MS/MS

3.2. Application of the First-Order Degradation Model for the Evaluation of Amino Acid Stability During Storage

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Campos, M.G.R.; Bogdanov, S.; de Almeida-Muradian, L.B.; Szczesna, T.; Mancebo, Y.; Frigerio, C.; Ferreira, F. Pollen composition and standardisation of analytical methods. J. Apic. Res. 2008, 47, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komosinska-Vassev, K.; Olczyk, P.; Kazmierczak, J.; Mencner, L.; Olczyk, K. Bee pollen: Chemical composition and therapeutic application. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2015, 2015, 297425. [Google Scholar]

- Kurek-Górecka, A.; Górecki, M.; Rzepecka-Stojko, A.; Balwierz, R.; Stojko, J. Bee products in dermatology and skin care. Molecules 2020, 25, 556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thakur, M.; Nanda, V. Composition and functionality of bee pollen: A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 98, 82–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasote, D.M. Propolis: A neglected product of value in the Indian beekeeping sector. Bee World 2017, 94, 80–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cianciosi, D.; Forbes-Hernández, T.Y.; Ansary, J.; Gil, E.; Amici, A.; Bompadre, S.; Simal-Gandara, J.; Giampieri, F.; Battino, M. Phenolic compounds from Mediterranean foods as nutraceutical tools for the prevention of cancer: The effect of honey polyphenols on colorectal cancer stem-like cells from spheroids. Food Chem. 2020, 325, 126881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canale, A.; Benelli, G.; Castagna, A.; Sgherri, C.; Poli, P.; Serra, A.; Mele, M.; Ranieri, A.; Signorini, F.; Bientinesi, M.; et al. Microwave-assisted drying for the conservation of honeybee pollen. Materials 2016, 9, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomás, A.; Falcão, S.I.; Russo-Almeida, P.; Vilas-Boas, M. Potentialities of beebread as a food supplement and source of nutraceuticals: Botanical origin, nutritional composition and antioxidant activity. J. Apic. Res. 2017, 56, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asmae, E.G.; Nawal, E.M.; Bakour, M.; Lyoussi, B. Moroccan monofloral bee pollen: Botanical origin, physicochemical characterization, and antioxidant activities. J. Food Qual. 2021, 2021, 8877266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, N.A.; Ahmed, O.M.; Hozayen, W.G.; Ahmed, M.A. Ameliorative effects of bee pollen and date palm pollen on the glycemic state and male sexual dysfunctions in streptozotocin-induced diabetic wistar rats. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 97, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruyama, H.; Sakamoto, T.; Araki, Y.; Hara, H. Anti-inflammatory effect of bee pollen ethanol extract from cistus sp. of spanish on carrageenan-induced rat hind paw edema. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2010, 10, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, J.S.; Chambó, E.D.; Costa, M.; Cavalcante da Silva, S.; Lopes de Carvalho, C.A.; Estevinho, L.M. Chemical composition and biological activities of mono-and heterofloral bee pollen of different geographical origins. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kafantaris, I.; Amoutzias, G.D.; Mossialos, D. Foodomics in bee product research: A systematic literature review. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2021, 247, 309–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaškonienė, V.; Adaškevičiūtė, V.; Kaškonas, P.; Mickienė, R.; Maruška, A. Antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of natural and fermented bee pollen. Food Biosci. 2020, 34, 100532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roulston, T.H.; Cane, J.H. Pollen nutritional content and digestibility for animals. Plant Syst. Evol. 2000, 222, 187–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liolios, V.; Tananaki, C.; Dimou, M.; Kanelis, D.; Goras, G.; Karazafiris, E.; Thrasyvoulou, A. Ranking pollen from bee plants according to their protein contribution to honey bees. J. Apic. Res. 2016, 54, 582–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Wu, D.; Ye, X.; Liu, D.; Chen, J.; Sun, P. Characterization of chemical composition of bee pollen in China. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61, 708–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rzepecka-Stojko, A.; Stojko, J.; Kurek-Górecka, A.; Górecki, M.; Kabała-Dzik, A.; Kubina, R.; Moździerz, A.; Buszman, E. Polyphenols from bee pollen: Structure, absorption, metabolism and biological activity. Molecules 2015, 20, 21732–21749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marghitas, L.A.; Stanciu, O.G.; Dezmirean, D.S.; Bobis, O.; Popescu, O.; Bogdanov, S.; Campos, M.G. In vitro antioxidant capacity of honeybee-collected pollen of selected floral origin harvested from Romania. Food Chem. 2009, 115, 878–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margaoan, R.; Marghitas, L.A.; Dezmirean, D.S.; Dulf, F.V.; Bunea, A.; Socaci, S.A.; Bobis, O. Predominant and secondary pollen botanical origins influence the carotenoid and fatty acid profile in fresh honeybee-collected pollen. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 6306–6316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayram, N.E.; Kostic, A.Z.; Gercek, Y.C. (Eds.) Pollen Chemistry & Biotechnology; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kölker, S. Metabolism of amino acid neurotransmitters: The synaptic disorder underlying inherited metabolic diseases. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2018, 41, 1055–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castagna, A.; Benelli, G.; Conte, G.; Sgherri, C.; Signorini, F.; Nicolella, C.; Ranieri, A.; Canale, A. Drying techniques and storage: Do they affect the nutritional value of bee-collected pollen. Molecules 2020, 25, 4925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G. Functional amino acids in nutrition and health. Amino Acids 2013, 45, 407–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, Z.L.; Wu, G.; Zhu, W.Y. Amino Acid Metabolism in Intestinal Bacteria: Links between Gut Ecology and Host Health. Front. Biosci. 2011, 16, 1768–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Z.L.; Li, X.L.; Xi, P.B.; Zhang, J.; Wu, G.; Zhu, W.Y. Regulatory Role for L-Arginine in the Utilization of Amino Acids by Pig Small-Intestinal Bacteria. Amino Acids 2012, 43, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkiewicz, I.P.; Wojdyło, A.; Tkacz, K.; Nowicka, P. Carotenoids, Chlorophylls, Vitamin E and Amino Acid Profile in Fruits of Nineteen Chaenomeles Cultivars. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2020, 93, 103608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botoran, O.R.; Ionete, R.E.; Miricioiu, M.G.; Costinel, D.; Radu, G.L.; Popescu, R. Amino acid profile of fruits as potential fingerprints of varietal origin. Molecules 2019, 24, 4500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.; An, H.; Wang, D. Characterization of amino acid composition in fruits of three Rosa roxburghii genotypes. Hortic. Plant J. 2017, 3, 232–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taha, E.K.; Al-Kahtani, S.; Taha, R. Protein content and amino acids composition of bee-pollens from major floral sources in Al-Ahsa, eastern Saudi Arabia. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2019, 26, 232–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Sharma, A.; Kaur, R.; Thukral, A.K.; Bhardwaj, R.; Ahmad, P. Differential distribution of amino acids in plants. Amino Acids 2017, 49, 821–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayram, N.E.; Gercek, Y.C.; Çelik, S.; Mayda, N.; Kostić, A.Ž.; Dramićanin, A.M.; Özkök, A. Phenolic and free amino acid profiles of bee bread and bee pollen with the same botanical origin–similarities and differences. Arab. J. Chem. 2021, 14, 103004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Themelis, T.; Gotti, R.; Orlandini, S.; Gatti, R. Quantitative amino acids profile of monofloral bee pollens by microwave hydrolysis and fluorimetric high performance liquid chromatography. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2019, 173, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ares, A.M.; Valverde, S.; Bernal, J.L.; Nozal, M.J.; Bernal, J. Extraction and determination of bioactive compounds from bee pollen. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2018, 147, 110–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almeida-Muradian, L.B.; Pamplona, L.C.; Coimbra, S.; Barth, O.M. Chemical composition and botanical evaluation of dried bee pollen pellets. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2005, 18, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palla, M.; Turrini, A.; Sbrana, C.; Signorini, F.; Nicolella, C.; Benelli, G.; Canale, A.; Giovannetti, M.; Agnolucci, M. Honeybee-collected pollen for human consumption: Impact of post-harvest conditioning on the microbiota. Agrochimica 2018, 2017, 57–68. [Google Scholar]

- Serra Bonvehí, J.; Soliva Torrentó, M.; Centelles Lorente, E. Evaluation of polyphenolic and flavonoid compounds in honeybee-collected pollen produced in Spain. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2001, 49, 1848–1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Ni, J.; Xue, X.; Zhou, Z.; Tian, W.; Orsat, V.; Yan, S.; Peng, W.; Fang, X. Effect of different drying methods on the amino acids, α-dicarbonyls and volatile compounds of rape bee pollen. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness 2024, 13, 517–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collin, S.; Vanhavre, T.; Odart, E.; Bouseta, A. Heat treatment of pollens: Impact on their volatile flavor constituents. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1995, 43, 444–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranieri, A.; Benelli, G.; Castagna, A.; Sgherri, C.; Signorini, F.; Bientinesi, M.; Nicolella, C.; Canale, A. Freeze-drying duration influences the amino acid and rutin content in honeybee-collected chestnut pollen. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2019, 26, 252–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conte, G.; Benelli, G.; Serra, A.; Signorini, F.; Bientinesi, M.; Nicolella, C.; Mele, M.; Canale, A. Lipid characterization of chestnut and willow honeybee-collected pollen: Impact of freeze-drying and microwave-assisted drying. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2017, 55, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De-Melo, A.A.M.; Estevinho, M.L.M.F.; Sattler, J.A.G.; Souza, B.R.; da Silva Freitas, A.; Barth, O.M.; Almeida-Muradian, L.B. Effect of processing conditions on characteristics of dehydrated bee-pollen and correlation between quality parameters. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 65, 808–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardana, C.; Del Bo, C.; Quicazán, M.C.; Corrrea, A.R.; Simonetti, P. Nutrients, phytochemicals and botanical origin of commercial bee pollen from different geographical areas. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2018, 29, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjos, O.; Seixas, N.; Antunes, C.A.L.; Campos, M.G.; Paula, V.; Estevinho, L.M. Quality of bee pollen submitted to drying, pasteurization, and high-pressure processing–A comparative approach. Food Res. Int. 2023, 170, 112964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feás, X.; Vázquez-Tato, M.P.; Estevinho, L.; Seijas, J.A.; Iglesias, A. Organic bee pollen: Botanical origin, nutritional value, bioactive compounds, antioxidant activity and microbiological quality. Molecules 2012, 17, 8359–8377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rzepecka-Stojko, A.; Stojko, J.; Kabała-Dzik, A.; Kubina, R.; Moździerz, A.; Stojko, R. Polyphenols and Amino Acids Profile of Bee Pollen from Poland and Their Antioxidant Activity. Molecules 2022, 27, 2471. [Google Scholar]

- Denisow, B.; Denisow-Pietrzyk, M. Biological and Nutritional Properties of Bee Pollen—A Review. J. Apic. Sci. 2023, 67, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Stebuliauskaitė, R.; Liaudanskas, M.; Žvikas, V.; Ceksterytė, V.; Sutkevičienė, N.; Sorkytė, Š.; Bračiulienė, A.; Trumbeckaite, S. Changes in Ascorbic Acid, Phenolic Compound Content, and Antioxidant Activity In Vitro in Bee Pollen Depending on Storage Conditions: Impact of Drying and Freezing. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahraman, H.A.; Tutun, H.; Kaya, M.M.; Usluer, M.S.; Tutun, S.; Yaman, C.; Keyvan, E. Ethanolic extract of turkish bee pollen and propolis: Phenolic composition, anti-radical, anti-proliferative, and antibacterial activity. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 2022, 36, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taujenis, L. Identification and Enantioselective Determination of Protein Amino Acids in Fertilizers by Hydrophilic Interaction and Chiral Chromatography Coupled to Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Ph.D. Thesis, Vilnius University, Vilnius, Lithuania, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lyu, J.; Liu, X.; Bi, J.; Wu, X.; Zhou, L.; Ruan, W.; Zhou, M.; Jiao, Y. Kinetic modelling of non-enzymatic browning and changes of physio-chemical parameters of peach juice during storage. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 55, 1003–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, S.; Kopuncová, M.; Ciesarová, Z.; Kukurová, K. Free amino acids profile of Polish and Slovak honeys based on LC-MS/MS method without the prior derivatisation. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 54, 3716–3723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castiglioni, S.; Astolfi, P.; Conti, C.; Monaci, E.; Stefano, M.; Carloni, P. Morphological, physicochemical and FTIR spectroscopic properties of bee pollen loads from different botanical origin. Molecules 2019, 24, 3974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Jin, L.; Chang, Q.; Peng, T.; Hu, X.; Fan, C.; Pang, G.; Lu, M.; Wang, W. Discrimination of botanical origins for Chinese honey according to free amino acids content by high-performance liquid chromatography with fluorescence detection with chemometric approaches. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2017, 97, 2042–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shubharani, R.; Sivaram, V.; Roopa, P. Assessment of honey plant resources through pollen analysis in Coorg honeys of Karnataka state. Int. J. Plant Reprod. Biol. 2012, 4, 31–39. [Google Scholar]

- Bryś, M.S.; Strachecka, A. The key role of amino acids in pollen quality and honey bee physiology: A review. Molecules 2024, 29, 2605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Somerville, D.C.; Nicol, H.I. Crude protein and amino acid composition of honey bee-collected pollen pellets from south-east Australia and a note on laboratory disparity. Aust. J. Exp. Agric. 2006, 46, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, P.S.; Wu, T.H.; Huang, M.Y.; Wang, D.Y.; Wu, M.C. Nutritive value of 11 bee pollen samples from major floral sources in Taiwan. Foods 2021, 10, 2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oroian, M.; Dranca, F.; Ursachi, F. Characterization of Romanian bee pollen—An important nutritional source. Foods 2022, 11, 2633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rzetecka, N.; Matuszewska, E.; Plewa, S.; Matysiak, J.; Klupczynska-Gabryszak, A. Bee products as valuable nutritional ingredients: Determination of broad free amino acid profiles in bee pollen, royal jelly, and propolis. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2024, 126, 105860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAulay, M.K.; Forrest, J.R.K. How do sunflower pollen mixtures affect survival of queenless microcolonies of bumblebees (Bombus impatiens) rrthropod. Arthropod Plant Interact. 2019, 13, 517–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somerville, D.C.; Nicol, H.I. Mineral content of honeybee-collected pollen from southern New SouthWales. Aust. J. Exp. Agric. 2002, 42, 1131–1136. [Google Scholar]

- Paramás, A.M.G.; Bárez, J.A.G.; Marcos, C.C.; García-Villanova, R.J.; Sánchez, J.S. HPLC-fluorimetric method for analysis of amino acids in products of the hive (honey and bee-pollen). Food Chem. 2006, 95, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ares, A.M.; Toribio, L.; Tapia, J.A.; González-Porto, A.V.; Higes, M.; Martín-Hernández, R.; Bernal, J. Differentiation of bee pollen samples according to the apiary of origin and harvesting period based on their amino acid content. Food Biosci. 2022, 50, 102092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Gómez, B.; Salahange, L.; Tapia, J.A.; Martín, M.T.; Ares, A.M.; Bernal, J. Fast chromatographic determination of free amino acids in bee pollen. Foods 2022, 11, 4013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeannerod, L.; Carlier, A.; Schatz, B.; Daise, C.; Richel, A.; Agnan, Y.; Baude, M.; Jacquemart, A.-L. Some bee-pollinated plants provide nutritionally incomplete pollen amino acid resources to their pollinators. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0269992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais, M.; Moreira, L.; Feás, X.; Estevinho, L.M. Bee pollen: Phenolic content, antioxidant activity and antimicrobial activity. Food Chem. 2011, 125, 110–115. [Google Scholar]

- Kayacan, S.; Sagdic, O.; Doymaz, I. Effects of hot-air and vacuum drying on drying kinetics, bioactive compounds and color of bee pollen. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2018, 12, 1274–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanar, Y.; Mazı, B.G. Effect of different drying methods on antioxidant characteristics of bee-pollen. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2019, 13, 3376–3386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isik, A.; Ozdemir, M.; Doymaz, I. Effect of hot air drying on quality characteristics and physicochemical properties of bee pollen. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 39, 224–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Z.; Pan, Y. Proteome analysis of tea pollen (Camellia sinensis) under different storage conditions. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 7535–7544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siuda, M.; Wilde, J.; Bąk, T. The effect of various storage methods on organoleptic quality of bee pollen loads. J. Apic. Sci. 2012, 56, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Arruda, V.A.S.; Pereira, A.A.S.; Estevinho, L.M.; de Almeida-Muradian, L.B. Presence and stability of B complex vitamins in bee pollen using different storage conditions. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2013, 51, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, L.; Zeng, X.; Han, Z.; Brennan, C.S. Non-thermal technologies and its current and future application in the food industry: A review. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 54, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahern, K.G.; Rajagopal, S.; Tan, J. Structure & function–amino acids. In Biochemistry Free for All; LibreTexts: Davis, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Dias, L.G.; Tolentino, G.; Pascoal, A.; Estevinho, L.M. Effect of processing conditions on the bioactive compounds and biological properties of bee pollen. J. Apic. Res. 2016, 55, 357–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Compound | Precursor Ion (m/z) | Product Ion (m/z) | Cone Voltage, V | Collision Energy, eV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Alanine | 90 | 44 | 16 | 10 |

| 2 | Arginine | 175 | 70 | 16 | 14 |

| 3 | Aspartic acid | 134 | 88 | 14 | 10 |

| 4 | Cysteine | 122 | 76 | 14 | 17 |

| 5 | Glutamic acid | 148 | 84 | 12 | 14 |

| 6 | Glycine | 76 | 30 | 12 | 6 |

| 7 | Histidine | 156 | 110 | 20 | 16 |

| 8 | Isoleucine | 132 | 86 | 16 | 10 |

| 9 | Leucine | 132 | 86 | 16 | 10 |

| 10 | Lysine | 147 | 84 | 14 | 14 |

| 11 | Methionine | 150 | 104 | 14 | 10 |

| 12 | Phenylalanine | 166 | 120 | 18 | 14 |

| 13 | Proline | 116 | 70 | 20 | 10 |

| 14 | Serine | 106 | 60 | 14 | 8 |

| 15 | Threonine | 120 | 74 | 38 | 20 |

| 16 | Tyrosine | 182 | 136 | 16 | 16 |

| 17 | Valine | 118 | 72 | 12 | 10 |

| No. | Amino Acid | C0 (µg/g) | k (Month−1) | R2 | t1/2 (Months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ala | 519.5 | 0.0104 | 0.9282 | 66.36 |

| 2 | Arg | 1145.0 | 0.0339 | 0.9216 | 20.48 |

| 3 | Asp | 965.8 | 0.0209 | 0.9857 | 33.22 |

| 4 | Cys | 14.2 | 0.4488 | 0.9444 | 1.54 |

| 5 | Glu | 740.6 | 0.0134 | 0.9658 | 51.57 |

| 6 | Gly | 297.2 | 0.0371 | 0.9256 | 18.67 |

| 7 | His | 599.3 | 0.0343 | 0.6817 | 20.23 |

| 8 | Ile | 147.9 | 0.0870 | 0.9541 | 7.97 |

| 9 | Leu | 470.3 | 0.0924 | 0.8651 | 7.50 |

| 10 | Lys | 256.3 | 0.0408 | 0.9099 | 17.00 |

| 11 | Met | 191.7 | 0.0502 | 0.9315 | 13.81 |

| 12 | Phe | 307.4 | 0.0170 | 0.9629 | 40.81 |

| 13 | Pro | 1133.9 | 0.0133 | 0.8776 | 51.93 |

| 14 | Ser | 397.7 | 0.0165 | 0.9487 | 42.08 |

| 15 | Thr | 187.9 | 0.0511 | 0.9941 | 13.56 |

| 16 | Tyr | 150.4 | 0.0303 | 0.9624 | 22.87 |

| 17 | Val | 354.2 | 0.0395 | 0.7576 | 17.55 |

| No. | Amino Acid | C0 (µg/g) | k (Month−1) | R2 | t1/2 (Months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ala | 518.5 | 0.0122 | 0.9594 | 56.86 |

| 2 | Arg | 1216.6 | 0.0837 | 0.9200 | 8.29 |

| 3 | Asp | 930.4 | 0.0232 | 0.9629 | 29.88 |

| 4 | Cys | 13.7 | 0.6025 | 0.9462 | 1.15 |

| 5 | Glu | 759.4 | 0.0104 | 0.9793 | 66.51 |

| 6 | Gly | 319.4 | 0.0308 | 0.8150 | 22.54 |

| 7 | His | 627.0 | 0.0478 | 0.8502 | 14.50 |

| 8 | Ile | 160.3 | 0.1022 | 0.9864 | 6.79 |

| 9 | Leu | 439.9 | 0.0942 | 0.8545 | 7.36 |

| 10 | Lys | 261.4 | 0.0296 | 0.9310 | 23.39 |

| 11 | Met | 199.1 | 0.1756 | 0.8132 | 3.95 |

| 12 | Phe | 316.7 | 0.0146 | 0.9622 | 47.61 |

| 13 | Pro | 1176.0 | 0.0149 | 0.8153 | 46.65 |

| 14 | Ser | 411.2 | 0.0173 | 0.9440 | 40.18 |

| 15 | Thr | 194.5 | 0.0343 | 0.8976 | 20.20 |

| 16 | Tyr | 170.5 | 0.0294 | 0.9390 | 23.55 |

| 17 | Val | 359.4 | 0.0487 | 0.7765 | 14.22 |

| No. | Amino Acid | C0 (µg/g) | k (Month−1) | R2 | t1/2 (Months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ala | 498.9 | 0.0270 | 0.8564 | 25.66 |

| 2 | Arg | 1164.5 | 0.0308 | 0.8890 | 22.5 |

| 3 | Asp | 903.8 | 0.0112 | 0.8527 | 62.06 |

| 4 | Cys | 10.2 | 0.9024 | 1.0000 | 0.77 |

| 5 | Glu | 696.1 | 0.0253 | 0.9979 | 27.35 |

| 6 | Gly | 281.1 | 0.0849 | 0.8699 | 8.16 |

| 7 | His | 568.7 | 0.0138 | 0.7486 | 50.29 |

| 8 | Ile | 129.1 | 0.0589 | 0.7577 | 11.78 |

| 9 | Leu | 420.0 | 0.0238 | 0.9348 | 29.18 |

| 10 | Lys | 244.6 | 0.0553 | 0.8916 | 12.53 |

| 11 | Met | 188.5 | 0.1380 | 0.9083 | 5.02 |

| 12 | Phe | 280.2 | 0.0285 | 0.9928 | 24.28 |

| 13 | Pro | 1026.7 | 0.0246 | 0.8595 | 28.14 |

| 14 | Ser | 354.8 | 0.0340 | 0.9134 | 20.36 |

| 15 | Thr | 172.1 | 0.0819 | 0.8892 | 8.46 |

| 16 | Tyr | 62.5 | 0.3189 | 0.9758 | 2.17 |

| 17 | Val | 350.4 | 0.0187 | 0.7457 | 36.99 |

| No. | Amino Acid | Q10 (−80 → −20) | Q10 (−20 → RT) | Q10 (−80 → RT) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ala | 0.975 | 1.268 | 1.083 |

| 2 | Arg | 0.860 | 0.977 | 0.905 |

| 3 | Asp | 0.982 | 0.855 | 0.930 |

| 4 | Cys | 0.952 | 1.191 | 1.041 |

| 5 | Glu | 1.043 | 1.172 | 1.093 |

| 6 | Gly | 1.032 | 1.230 | 1.107 |

| 7 | His | 0.946 | 0.796 | 0.883 |

| 8 | Ile | 0.974 | 0.907 | 0.946 |

| 9 | Leu | 0.997 | 0.712 | 0.871 |

| 10 | Lys | 1.055 | 1.079 | 1.064 |

| 11 | Met | 0.812 | 1.288 | 0.976 |

| 12 | Phe | 1.026 | 1.139 | 1.070 |

| 13 | Pro | 0.982 | 1.166 | 1.052 |

| 14 | Ser | 0.992 | 1.199 | 1.070 |

| 15 | Thr | 1.069 | 1.125 | 1.091 |

| 16 | Tyr | 1.005 | 1.801 | 1.269 |

| 17 | Val | 0.966 | 0.830 | 0.909 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Bračiulienė, A.; Stebuliauskaitė, R.; Liaudanskas, M.; Žvikas, V.; Sutkevičienė, N.; Trumbeckaitė, S. Changes in the Amino Acid Composition of Bee-Collected Pollen During 15 Months of Storage in Fresh-Frozen and Dried Forms. Foods 2026, 15, 207. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15020207

Bračiulienė A, Stebuliauskaitė R, Liaudanskas M, Žvikas V, Sutkevičienė N, Trumbeckaitė S. Changes in the Amino Acid Composition of Bee-Collected Pollen During 15 Months of Storage in Fresh-Frozen and Dried Forms. Foods. 2026; 15(2):207. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15020207

Chicago/Turabian StyleBračiulienė, Aurita, Rosita Stebuliauskaitė, Mindaugas Liaudanskas, Vaidotas Žvikas, Neringa Sutkevičienė, and Sonata Trumbeckaitė. 2026. "Changes in the Amino Acid Composition of Bee-Collected Pollen During 15 Months of Storage in Fresh-Frozen and Dried Forms" Foods 15, no. 2: 207. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15020207

APA StyleBračiulienė, A., Stebuliauskaitė, R., Liaudanskas, M., Žvikas, V., Sutkevičienė, N., & Trumbeckaitė, S. (2026). Changes in the Amino Acid Composition of Bee-Collected Pollen During 15 Months of Storage in Fresh-Frozen and Dried Forms. Foods, 15(2), 207. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15020207