Optimization of Ultrasonic Enzyme-Assisted Extraction for the Recovery of Phenolic Compounds and Soluble Solids from Apple Pomace

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material and Pomace Preparation

2.2. Chemicals

2.3. Experimental Design

2.4. Extraction of Apple Pomace in Water

2.5. Soluble Solids Content

2.6. Total Phenolic Content

2.7. DPPH Radical Scavenging Activity

2.8. Quantification of Phenolic Compounds

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

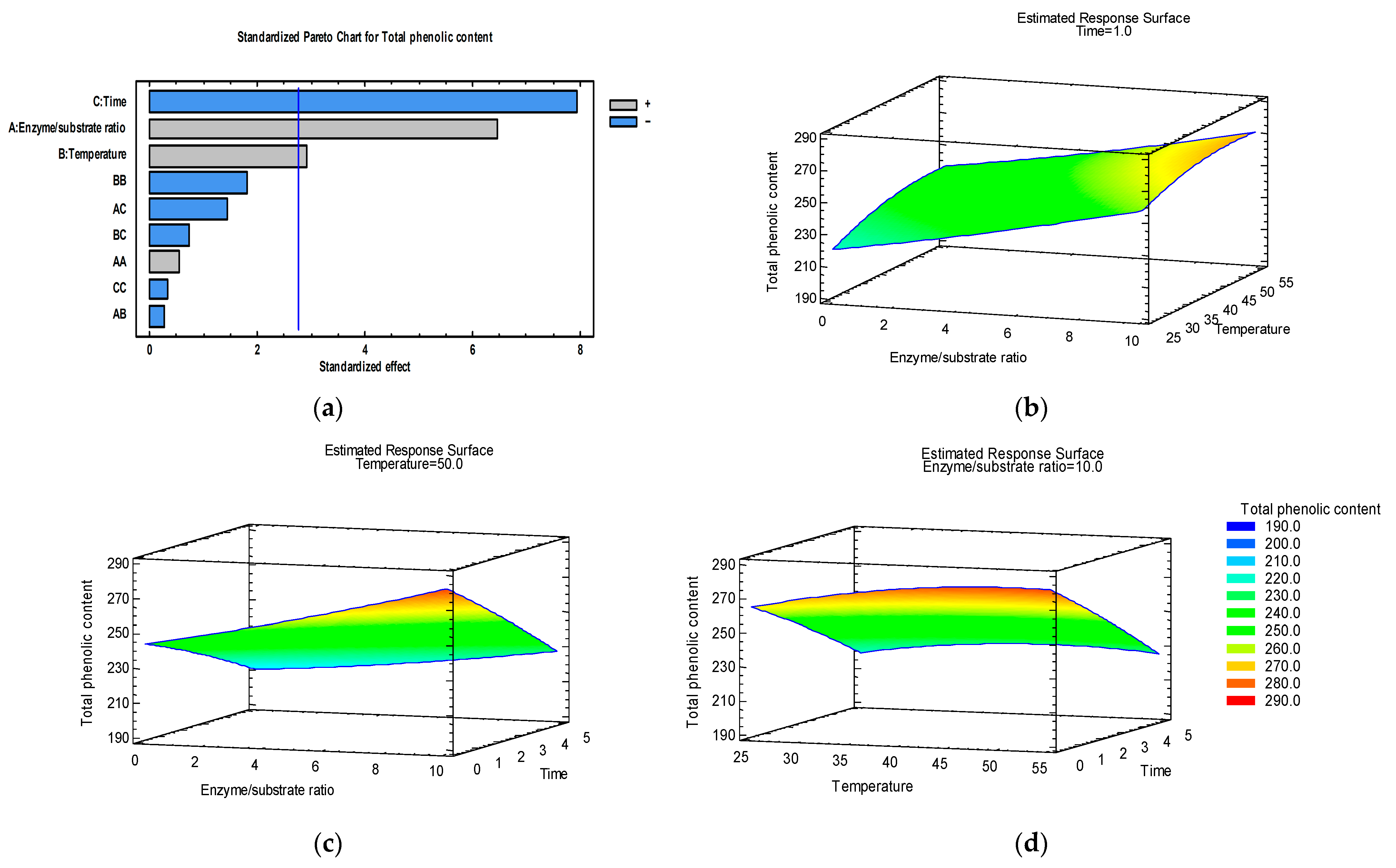

3.1. Optimization of Total Phenolic Content

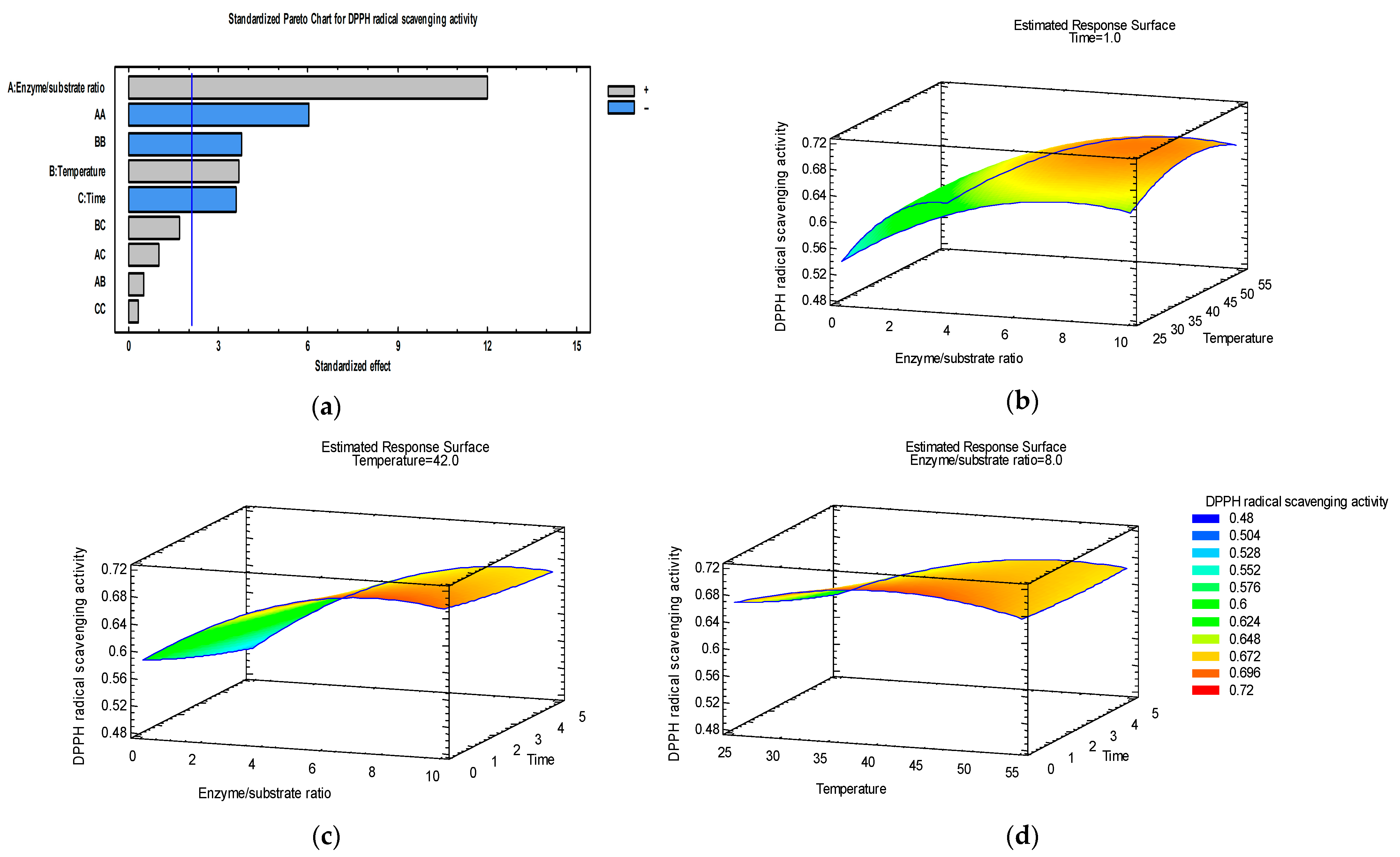

3.2. Optimization of DPPH Radical Scavenging Activity

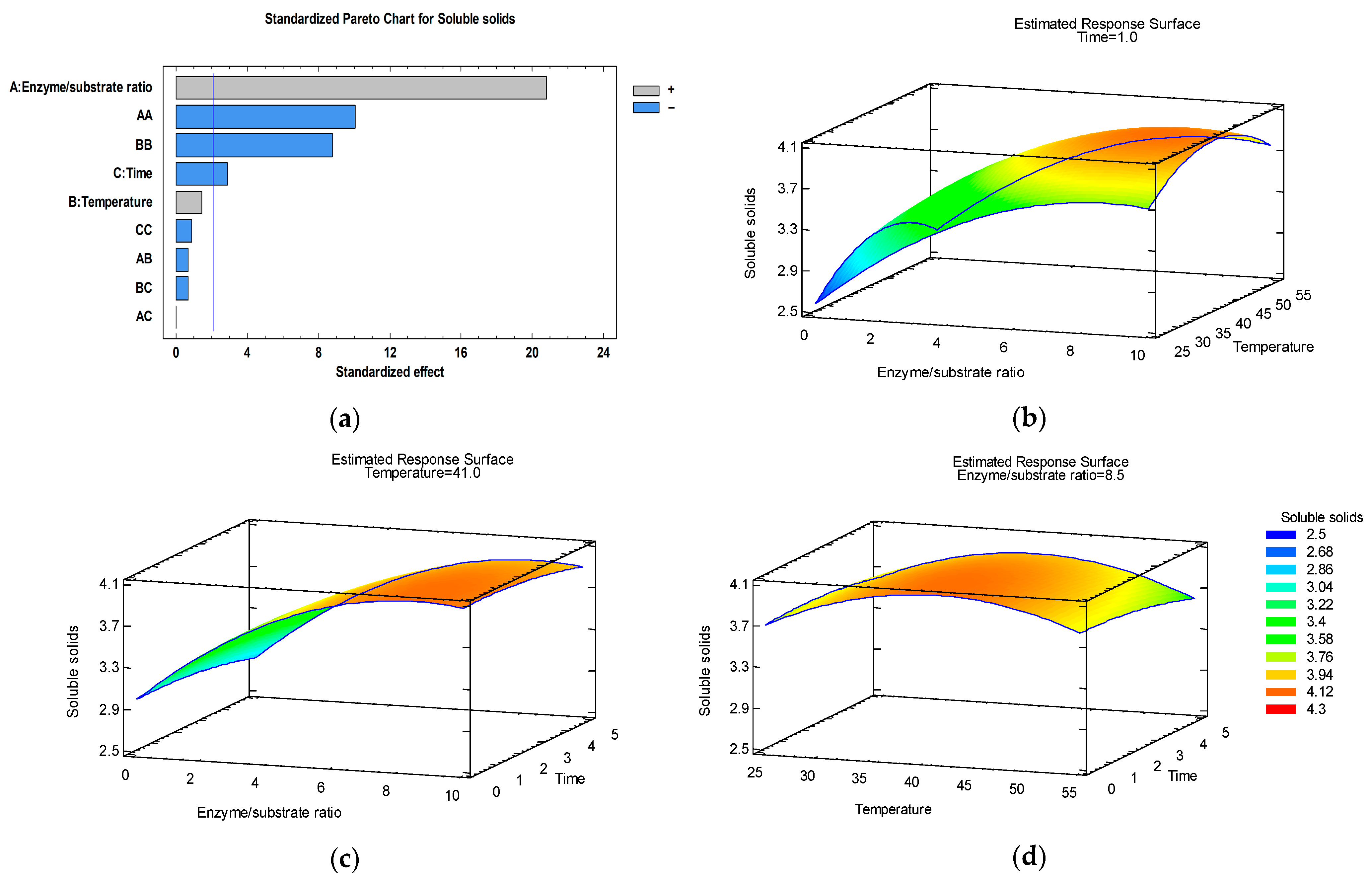

3.3. Optimization of Soluble Solids Content

3.4. Simultaneous Response Optimization

3.5. Phenolic Characterization of Apple Pomace Extracts

4. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAOSTAT. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#home (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Shalini, R.; Gupta, D.K. Utilization of Pomace from Apple Processing Industries: A Review. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2010, 47, 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perussello, C.A.; Zhang, Z.; Marzocchella, A.; Tiwari, B.K. Valorization of Apple Pomace by Extraction of Valuable Compounds. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2017, 16, 776–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kammerer, D.R.; Kammerer, J.; Valet, R.; Carle, R. Recovery of Polyphenols from the By-Products of Plant Food Processing and Application as Valuable Food Ingredients. Food Res. Int. 2014, 65, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vendruscolo, F.; Albuquerque, P.M.; Streit, F.; Esposito, E.; Ninow, J.L. Apple Pomace: A Versatile Substrate for Biotechnological Applications. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2008, 28, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, F.; Luiz, S.F.; Azeredo, D.R.P.; Cruz, A.G.; Ajlouni, S.; Ranadheera, C.S. Apple Pomace as a Functional and Healthy Ingredient in Food Products: A Review. Processes 2020, 8, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez, B.; Álvarez, Á.L.; García, Y.D.; del Barrio, G.; Lobo, A.P.; Parra, F. Phenolic profiles, antioxidant activity and in vitro antiviral properties of apple pomace. Food Chem. 2010, 120, 339–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, R.C.; Gigliotti, J.C.; Ku, K.M.; Tou, J.C. A Comprehensive Analysis of the Composition, Health Benefits, and Safety of Apple Pomace. Nutr. Rev. 2018, 76, 893–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonic, B.; Jancikova, S.; Dordevic, D.; Tremlova, B. Apple pomace as food fortification ingredient: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Food Sci. 2020, 85, 2977–2985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhillon, G.S.; Kaur, S.; Brar, S.K. Perspective of Apple Processing Wastes as Low-Cost Substrates for Bioproduction of High Value Products: A Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 27, 789–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, S.F.; Rai, D.K.; Abu-Ghannam, N. Apple pomace as a potential ingredient for the development of new functional foods. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 49, 1743–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhushan, S.; Kalia, K.; Sharma, M.; Singh, B.; Ahuja, P.S. Processing of apple pomace for bioactive molecules. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2008, 28, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konrade, D.; Klava, D.; Gramatina, I. Cereal Crispbread Improvement with Dietary Fibre from Apple By-Products. CBU Int. Conf. Proc. 2017, 5, 1143–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putra, N.R.; Rizkiyah, D.N.; Abdul Aziz, A.H.; Che Yunus, M.A.; Veza, I.; Harny, I.; Tirta, A. Waste to wealth of apple pomace valorization by past and current extraction processes: A review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, P.A.R.; Ferreira, S.S.; Bastos, R.; Ferreira, I.; Cruz, M.T.; Pinto, A.; Coelho, E.; Passos, C.P.; Coimbra, M.A.; Cardoso, S.M.; et al. Apple pomace extract as a sustainable food ingredient. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asma, U.; Morozova, K.; Ferrentino, G.; Scampicchio, M. Apples and Apple By-Products: Antioxidant Properties and Food Applications. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Resolution Adopted by the General Assembly on 25 September 2015, 526 A/RES/70/1. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015; p. 527. Available online: https://undocs.org/en/A/RES/70/1 (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Thomas, F.; Abebe, G.; Emenike, C.; Martynenko, A. Sustainable utilization of apple pomace: Technological aspects and emerging applications. Food Res. Int. 2025, 220, 117149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basegmez, H.I.O.; Povilaitis, D.; Kitrytė, V.; Kraujalienė, V.; Šulniūtė, V.; Alasalvar, C.; Venskutonis, P.R. Biorefining of blackcurrant pomace into high value functional ingredients using supercritical CO2, pressurized liquid and enzyme assisted extractions. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2017, 124, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syrpas, M.; Valanciene, E.; Augustiniene, E.; Malys, N. Valorization of Bilberry (Vaccinium myrtillus L.) Pomace by Enzyme-Assisted Extraction: Process Optimization and Comparison with Conventional Solid-Liquid Extraction. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, R.; Barbosa, A.; Advinha, B.; Sales, H.; Pontes, R.; Nunes, J. Green Extraction Techniques of Bioactive Compounds: A State-of-the-Art Review. Processes 2023, 11, 2255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitrytė, V.; Kavaliauskaitė, A.; Tamkutė, L.; Pukalskienė, M.; Syrpas, M.; Rimantas Venskutonis, P. Zero waste biorefining of lingonberry (Vaccinium vitis-idaea L.) pomace into functional ingredients by consecutive high pressure and enzyme assisted extractions with green solvents. Food Chem. 2020, 322, 126767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaky, A.A.; Witrowa-Rajchert, D.; Nowacka, M. Turning Apple Pomace into Value: Sustainable Recycling in Food Production—A Narrative Review. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rifna, E.J.; Misra, N.N.; Dwivedi, M. Recent advances in extraction technologies for recovery of bioactive compounds derived from fruit and vegetable waste peels: A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 63, 719–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Riaz, S.; Sameen, A.; Naumovski, N.; Iqbal, M.W.; Rehman, A.; Mehany, T.; Zeng, X.-A.; Manzoor, M.F. The Disposition of Bioactive Compounds from Fruit Waste, Their Extraction, and Analysis Using Novel Technologies: A Review. Processes 2022, 10, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; P, N.; Kumar, M.; Jose, A.; Tomer, V.; Oz, E.; Proestos, C.; Zeng, M.; Elobeid, T.; K, S. Major phytochemicals: Recent advances in health benefits and extraction method. Molecules 2023, 28, 887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubaidi, M.A.; Czaplicka, M.; Kolniak-Ostek, J.; Nawirska-Olszańska, A. Effect of Different Enzyme Treatments on Juice Yield, Physicochemical Properties, and Bioactive Compound of Several Hybrid Grape Varieties. Molecules 2025, 30, 556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapasakalidis, P.G.; Rastall, R.A.; Gordon, M.H. Effect of a cellulase treatment on extraction of antioxidant phenols from black currant (Ribes nigrum L.) pomace. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 4342–4351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, M.J.A.; Carrera, C.; Barbero, G.F.; Palma, M. A comparison study between ultrasound–assisted and enzyme–assisted extraction of anthocyanins from blackcurrant (Ribes nigrum L.). Food Chem. X 2022, 13, 100192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitrytė, V.; Kraujalienė, V.; Šulniūtė, V.; Pukalskas, A.; Venskutonis, P.R. Chokeberry pomace valorization into food ingredients by enzyme-assisted extraction: Process optimization and product characterization. Food Bioprod. Process. 2017, 105, 36–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, A.; Pereira, A.L.D.; Barbero, G.F.; Martinez, J. Recovery of anthocyanins from residues of Rubus fruticosus, Vaccinium myrtillus and Eugenia brasiliensis by ultrasound assisted extraction, pressurized liquid extraction and their combination. Food Chem. 2017, 231, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitrytė, V.; Narkevičiūtė, A.; Tamkutė, L.; Syrpas, M.; Pukalskienė, M.; Venskutonis, P.R. Consecutive high-pressure and enzyme assisted fractionation of blackberry (Rubus fruticosus L.) pomace into functional ingredients: Process optimization and product characterization. Food Chem. 2020, 312, 126072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klavins, L.; Kviesis, J.; Nakurte, I.; Klavins, M. Berry press residues as a valuable source of polyphenolics: Extraction optimization and analysis. LWT 2018, 93, 583–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez-Rodríguez, G.; Marina, M.L.; Plaza, M. Enzyme-assisted extraction of bioactive non-extractable polyphenols from sweet cherry (Prunus avium L.) pomace. Food Chem. 2021, 339, 128086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-García, R.; Martínez-Ávila, G.C.G.; Aguilar, C.N. Enzyme-assisted extraction of antioxidative phenolics from grape (Vitis vinifera L.) residues. 3 Biotech 2012, 2, 297–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascaes Teles, A.S.; Hidalgo Chávez, D.W.; Zarur Coelho, M.A.; Rosenthal, A.; Fortes Gottschalk, L.M.; Tonon, R.V. Combination of Enzyme-Assisted Extraction and High Hydrostatic Pressure for Phenolic Compounds Recovery from Grape Pomace. J. Food Eng. 2021, 288, 110128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Freitas, B.S.M.; Pereira-Coelho, M.; De Almeida, A.B.; De Almeida, J.D.S.O.; Egea, M.B.; Da Silva, F.G.; Petkowicz, C.L.; de Francisco, A.; Madureira, L.A.; Freire, C.B.F.; et al. Cerrado cashew (Anacardium othonianum Rizz) apple pomace: Chemical characterization and optimization of enzyme-assisted extraction of phenolic compounds. Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 43, e90222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macedo, G.A.; Santana, Á.L.; Crawford, L.M.; Wang, S.C.; Dias, F.F.G.; De Moura Bell, J.M.L.N. Integrated Microwave- and Enzyme-Assisted Extraction of Phenolic Compounds from Olive Pomace. LWT 2021, 138, 110621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitrytė, V.; Povilaitis, D.; Kraujaliene, V.; Sulniute, V.; Pukalskas, A.; Venskutonis, P.R. Fractionation of sea buckthorn pomace and seeds into valuable components by using high pressure and enzyme-assisted extraction methods. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 85, 534–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadar, S.S.; Rao, P.; Rathod, V.K. Enzyme assisted extraction of biomolecules as an approach to novel extraction technology: A review. Food Res. Int. 2018, 108, 309–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Guo, Y.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, H.; Shang, H. Ultrasonic enzyme-assisted extraction of comfrey (Symphytum officinale L.) polysaccharides and their digestion and fermentation behaviors In Vitro. Process Biochem. 2022, 112, 98–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tchabo, W.; Ma, Y.; Engmann, F.N.; Zhang, H. Ultrasound-Assisted Enzymatic Extraction (UAEE) of Phytochemical Compounds from Mulberry (Morus Nigra) Must and Optimization Study Using Response Surface Methodology. Ind. Crops Prod. 2015, 63, 214–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Mao, Y.-D.; Wang, Y.-F.; Raza, A.; Qiu, L.-P.; Xu, X.-Q. Optimization of Ultrasonic-Assisted Enzymatic Extraction Conditions for Improving Total Phenolic Content, Antioxidant and Antitumor Activities In Vitro from Trapa Quadrispinosa Roxb. Residues. Molecules 2017, 22, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanek-Wandzel, N.; Zarębska, M.; Wasilewski, T.; Hordyjewicz-Baran, Z.; Krzyszowska, A.; Gębura, K.; Tomaka, M. Enhancing phenolic compound recovery from red and white grape pomace residues using a synergistic ultrasound-and enzyme-assisted extraction approach (cellulase, hemicellulase, and pectinase treatments). ACS Omega 2025, 10, 23129–23138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keskin Gündoğdu, T.; Deniz, İ.; Çalışkan, G.; Şahin, E.S.; Azbar, N. Experimental design methods for bioengineering applications. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2016, 36, 368–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ćujić, N.; Savikin, K.; Jankovic, T.; Pljevljakusic, D.; Zdunic, G.; Ibric, S. Optimization of polyphenols extraction from dried chokeberry using maceration as traditional technique. Food Chem. 2016, 194, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Association of Official Analytical Chemistry. Official Methods of Analysis, 18th ed.; Analytical Chemists: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Angelov, A.; Übelacker, M.; Baudrexl, M.; Ludwig, C.; Rühmann, B.; Sieber, V.; Liebl, W. Proteomic Analysis of Viscozyme L and Its Major Enzyme Components for Pectic Substrate Degradation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 266, 131309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOAC. Method of Analysis; Association of Official Analytical Chemistry: Washington, DC, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Singleton, V.L.; Orthofer, R.; Lamuela-Raventos, R.M. Analysis of total phenols and other oxidation substrates and antioxidants by means of Folin-Ciocalteau reagent. Methods Enzymol. 1999, 299, 152–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand-Williams, W.; Cuvelier, M.E.; Berset, C. Use of a free radical method to evaluate antioxidant activity. Lebensm. Wissen. Technol. 1995, 28, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nour, V.; Trandafir, I.; Cosmulescu, S. HPLC determination of phenolic acids, flavonoids and juglone in walnut leaves. J. Chromatogr. Sci. 2013, 51, 883–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuorro, A.; Lavecchia, R.; González-Delgado, D.; García-Martinez, J.B.; L’Abbate, P. Optimization of Enzyme-Assisted Extraction of Flavonoids from Corn Husks. Processes 2019, 7, 804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barcelos, M.C.S.; Ramos, C.L.; Kuddus, M.; Rodriguez-Couto, S.; Srivastava, N.; Ramteke, P.W.; Mishra, P.K.; Molina, G. Enzymatic Potential for the Valorization of Agro-Industrial by-Products. Biotechnol. Lett. 2020, 42, 1799–1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepaus, B.M.; Valiati, B.S.; Machado, B.G.; Domingos, M.M.; Silva, M.N.; Faria-Silva, L.; Bernardes, P.C.; Oliveira, D.d.S.; de São José, J.F.B. Impact of ultrasound processing on the nutritional components of fruit and vegetable juices. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 138, 752–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollini, L.; Cossignani, L.; Juan, C.; Mañes, J. Extraction of phenolic compounds from fresh apple pomace by different non-conventional techniques. Molecules 2021, 26, 4272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Kantar, S.; Boussetta, N.; Rajha, H.N.; Maroun, R.G.; Louka, N.; Vorobiev, E. High Voltage Electrical Discharges Combined with Enzymatic Hydrolysis for Extraction of Polyphenols and Fermentable Sugars from Orange Peels. Food Res. Int. 2018, 107, 755–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanek-Wandzel, N.; Krzyszowska, A.; Zarębska, M.; Gębura, K.; Wasilewski, T.; Hordyjewicz-Baran, Z.; Tomaka, M. Evaluation of Cellulase, Pectinase, and Hemicellulase Effectiveness in Extraction of Phenolic Compounds from Grape Pomace. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 13538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrov Ivanković, A.; Milivojević, A.; Ćorović, M.; Simović, M.; Banjanac, K.; Jansen, P.; Vukoičić, A.; van den Bogaard, E.; Bezbradica, D. In Vitro Evaluation of Enzymatically Derived Blackcurrant Extract as Prebiotic Cosmetic Ingredient: Extraction Conditions Optimization and Effect on Cutaneous Microbiota Representatives. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2023, 10, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, M.; Louvet, F.; Meudec, E.; Landolt, C.; Grenier, K.; Périno, S.; Ouk, T.-S.; Saad, N. Optimized Single-Step Recovery of Lipophilic and Hydrophilic Compounds from Raspberry, Strawberry and Blackberry Pomaces Using a Simultaneous Ultrasound-Enzyme-Assisted Extraction (UEAE). Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, X.; Hu, Y.; Wang, N.; Zhou, Z.; Liu, Z. Continuous juice concentration by integrating forward osmosis with membrane distillation using potassium sorbate preservative as a draw solute. J. Membr. Sci. 2019, 573, 192–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, F.; Cao, X.; Ge, L.; Zhang, J.; Guo, Y.; Li, S.; Li, Z. Sustainable apple juice concentration: A fusion of pasteurization and membrane distillation. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2024, 208, 753–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.W.; Baek, J.; Kim, W.-J. Forward osmosis and direct contact membrane distillation: Emerging membrane technologies in food and beverage processing. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2024, 93, 103626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcillo-Parra, V.; Tupuna-Yerovi, D.S.; González, Z.; Ruales, J. Encapsulation of Bioactive Compounds from Fruit and Vegetable By-Products for Food Application—A Review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 116, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltani Firouz, M.; Farahmandi, A.; Hosseinpour, S. Recent advances in ultrasound application as a novel technique in analysis, processing and quality control of fruits, juices and dairy products industries: A review. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2019, 57, 73–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waldbauer, K.; McKinnon, R.; Kopp, B. Apple Pomace as Potential Source of Natural Active Compounds. Planta Med. 2017, 83, 994–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plamada, D.; Arlt, M.; Güterbock, D.; Sevenich, R.; Kanzler, C.; Neugart, S.; Vodnar, D.C.; Kieserling, H.; Rohn, S. Impact of Thermal, High-Pressure, and Pulsed Electric Field Treatments on the Stability and Antioxidant Activity of Phenolic-Rich Apple Pomace Extracts. Molecules 2024, 29, 5849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Independent variables | Coded values | ||

| −1 | 0 | +1 | |

| Actual values | |||

| x1: Enzyme/substrate ratio (%) | 0 | 5 | 10 |

| x2: Temperature (°C) | 25 | 40 | 55 |

| x3: Extraction time (h) | 1 | 3 | 5 |

| Process Parameters (Actual Values) | Total Phenolic Content (mg GAE/L) | DPPH Radical Scavenging Activity (mmol Trolox/L) | Soluble Solids Content (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enzyme/Substrate Ratio (%, v/w) | Temperature (°C) | Extraction Time (h) | |||

| 5 | 55 | 5 | 204.27 ± 6.36 | 0.63 ± 0.02 | 3.35 ± 0.05 |

| 0 | 40 | 1 | 235.18 ± 2.64 | 0.57 ± 0.03 | 2.95 ± 0.10 |

| 10 | 40 | 1 | 255.64 ± 5.43 | 0.67 ± 0.02 | 3.95 ± 0.07 |

| 5 | 40 | 3 | 233.36 ± 1.93 | 0.66 ± 0.04 | 3.82 ± 0.05 |

| 10 | 40 | 5 | 227.91 ± 6.07 | 0.66 ± 0.01 | 3.95 ± 0.00 |

| 5 | 25 | 5 | 206.55 ± 3.86 | 0.57 ± 0.00 | 3.35 ± 0.07 |

| 5 | 40 | 3 | 227.91 ± 0.64 | 0.65 ± 0.02 | 3.90 ± 0.05 |

| 5 | 40 | 3 | 243.82 ± 5.14 | 0.65 ± 0.03 | 3.87 ± 0.05 |

| 0 | 40 | 5 | 224.27 ± 4.50 | 0.53 ± 0.02 | 2.95 ± 0.10 |

| 5 | 25 | 1 | 248.36 ± 7.71 | 0.65 ± 0.00 | 3.60 ± 0.00 |

| 10 | 55 | 3 | 262.00 ± 1.29 | 0.67 ± 0.02 | 3.75 ± 0.05 |

| 0 | 25 | 3 | 198.82 ± 5.17 | 0.49 ± 0.03 | 2.53 ± 0.03 |

| 5 | 55 | 1 | 254.73 ± 3.77 | 0.65 ± 0.03 | 3.72 ± 0.05 |

| 10 | 25 | 3 | 241.55 ± 4.35 | 0.62 ± 0.02 | 3.70 ± 0.07 |

| 0 | 55 | 3 | 222.15 ± 3.21 | 0.53 ± 0.03 | 2.65 ± 0.10 |

| Regression Coefficients | Total Phenolic Content | DPPH Radical Scavenging Activity | Soluble Solids Content |

|---|---|---|---|

| β0 | 173.174 * (0.0000) | 0.384421 * (0.0000) | 0.346296 * (0.0000) |

| β1 (enzyme/substrate ratio) | 3.65367 * (0.0030) | 0.0269583 * (0.0000) | 0.274167 * (0.0000) |

| β2 (temperature) | 2.64315 (0.0432) | 0.0103102 * (0.0018) | 0.125185 (0.1630) |

| β3 (extraction time) | −1.69729 * (0.0014) | −0.0332292 * (0.0031) | 0.0458333 * (0.0091) |

| β12 | −0.0106 (0.8496) | 0.00005 (0.6256) | −0.000333333 (0.5022) |

| β13 | −0.42025 (0.3222) | 0.000625 (0.4187) | 0.0 (1.0000) |

| β23 | −0.0719583 (0.6076) | 0.000416667 (0.1147) | −0.000833333 (0.4410) |

| β11 | 0.0690083 (0.6930) | −0.00183333 * (0.0000) | −0.0153333 * (0.0000) |

| β22 | −0.0246602 (0.2128) | −0.000131481 * (0.0013) | −0.00148148 * (0.0000) |

| β33 | −0.250885 (0.8181) | 0.000729167 (0.7150) | −0.00833333 (0.3918) |

| p-value | 0.0003 | 0.0003 | 0.0003 |

| R2 | 75.8336 | 92.1611 | 96.982 |

| Goal | Lower Limit | Upper Limit | Impact | Solution | Actual Responses | Desirability | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x1: Enzyme/substrate ratio (%) | In range | 0 | 10 | 3 | 9.777 | - | - |

| x2: Temperature (°C) | In range | 25 | 55 | 3 | 43.073 | - | - |

| x3: Extraction time (h) | In range | 1 | 5 | 3 | 1.000 | - | - |

| Total phenolic content (mg GAE/L) | Maximize | 193.82 | 262.91 | 3 | 269.973 | 269.678 | 98.09 |

| DPPH radical scavenging activity (mmol Trolox/L) | Maximize | 0.49 | 0.69 | 3 | 0.684 | 0.692 | 97.53 |

| Soluble solids content (%) | Maximize | 2.5 | 4.0 | 3 | 4.0658 | 4.114 | 99.37 |

| Total Phenolic Content | DPPH Radical Scavenging Activity | Soluble Solids Content | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total phenolic content | 1 | 0.84979 * (0.0001) | 0.591497 * (0.0006) |

| DPPH radical scavenging activity | 1 | 0.921153 * (0.0000) | |

| Soluble solids content | 1 |

| Phenolic Compound | APE 0-40-1 | APE 0-40-5 | APE 10-40-1 | APE 10-40-5 | APE 5-55-1 | APE 5-55-5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vanillic acid | 0.34 ± 0.02 cd | 0.39 ± 0.02 b | 0.44 ± 0.02 a | 0.31 ± 0.01 d | 0.35 ± 0.02 c | 0.39 ± 0.01 b |

| Rutin | 1.42 ± 0.05 d | 3.50 ± 0.22 a | 1.78 ± 0.08 c | 1.59 ± 0.06 cd | 1.58 ± 0.07 cd | 2.37 ± 0.11 b |

| Quercetin | 0.08 ± 0.01 d | 0.03 ± 0.00 e | 0.19 ± 0.01 b | 0.14 ± 0.01 cd | 0.31 ± 0.02 a | 0.33 ± 0.02 a |

| Gallic acid | 0.06 ± 0.01 c | 0.15 ± 0.02 a | 0.05 ± 0.01 c | 0.10 ± 0.01 b | 0.04 ± 0.00 c | 0.10 ± 0.01 b |

| Catechin hydrate | 0.37 ± 0.02 c | 0.56 ± 0.04 a | 0.27 ± 0.03 d | 0.44 ± 0.03 b | 0.47 ± 0.03 b | 0.49 ± 0.03 b |

| Syringic acid | 0.08 ± 0.01 d | 0.05 ± 0.01 e | 0.12 ± 0.01 c | 0.20 ± 0.02 b | 0.03 ± 0.00 e | 0.32 ± 0.02 a |

| Epicatechin | 1.61 ± 0.08 c | 1.08 ± 0.05 d | 2.17 ± 0.13 a | 1.92 ± 0.08 b | 1.23 ± 0.07 d | 1.75 ± 0.11 c |

| Trans cinnamic acid | 0.02 ± 0.00 b | 0.01 ± 0.00 b | 0.06 ± 0.01 a | 0.06 ± 0.01 a | 0.05 ± 0.01 a | 0.05 ± 0.01 a |

| Chlorogenic acid | 16.02 ± 0.31 c | 11.81 ± 0.37 e | 23.71 ± 0.67 a | 15.18 ± 0.45 d | 20.41 ± 0.57 b | 8.57 ± 0.23 f |

| Caffeic acid | 1.34 ± 0.08 e | 2.33 ± 0.02 c | 1.58 ± 0.07 d | 3.32 ± 0.13 a | 1.25 ± 0.05 e | 2.85 ± 0.12 b |

| Coumaric acid | 0.51 ± 0.03 e | 0.06 ± 0.02 f | 0.60 ± 0.02 d | 0.92 ± 0.04 a | 0.51 ± 0.02 e | 0.84 ± 0.03 b |

| Ferulic acid | 0.08 ± 0.01 c | 0.11 ± 0.01 d | 0.78 ± 0.01 a | 0.75 ± 0.04 a | 0.37 ± 0.01 b | 0.27 ± 0.02 b |

| Total | 91.30 ± 0.63 d | 80.76 ± 0.78 e | 125.71 ± 1.07 a | 98.32 ± 0.89 c | 105.95 ± 0.87 b | 73.21 ± 0.72 f |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Nour, V. Optimization of Ultrasonic Enzyme-Assisted Extraction for the Recovery of Phenolic Compounds and Soluble Solids from Apple Pomace. Foods 2026, 15, 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010098

Nour V. Optimization of Ultrasonic Enzyme-Assisted Extraction for the Recovery of Phenolic Compounds and Soluble Solids from Apple Pomace. Foods. 2026; 15(1):98. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010098

Chicago/Turabian StyleNour, Violeta. 2026. "Optimization of Ultrasonic Enzyme-Assisted Extraction for the Recovery of Phenolic Compounds and Soluble Solids from Apple Pomace" Foods 15, no. 1: 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010098

APA StyleNour, V. (2026). Optimization of Ultrasonic Enzyme-Assisted Extraction for the Recovery of Phenolic Compounds and Soluble Solids from Apple Pomace. Foods, 15(1), 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010098