Edible Yellow Mealworm-Derived Antidiabetic Peptides: Dual Modulation of α-Glucosidase and Dipeptidyl-Peptidase IV Inhibition Revealed by Integrated Proteomics, Bioassays, and Molecular Docking Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents

2.2. Pretreatments of Yellow Mealworm Larvae

2.3. Identification of Bioactive Peptides from Yellow Mealworm Larvae

2.4. In Silico Screenings of Bioactive Peptides

2.5. Inhibitory Effects of Bioactive Peptides on α-Glucosidase and DPP-IV

2.6. Establishment of Cell Cultures and the IR-HepG2 Cell Model

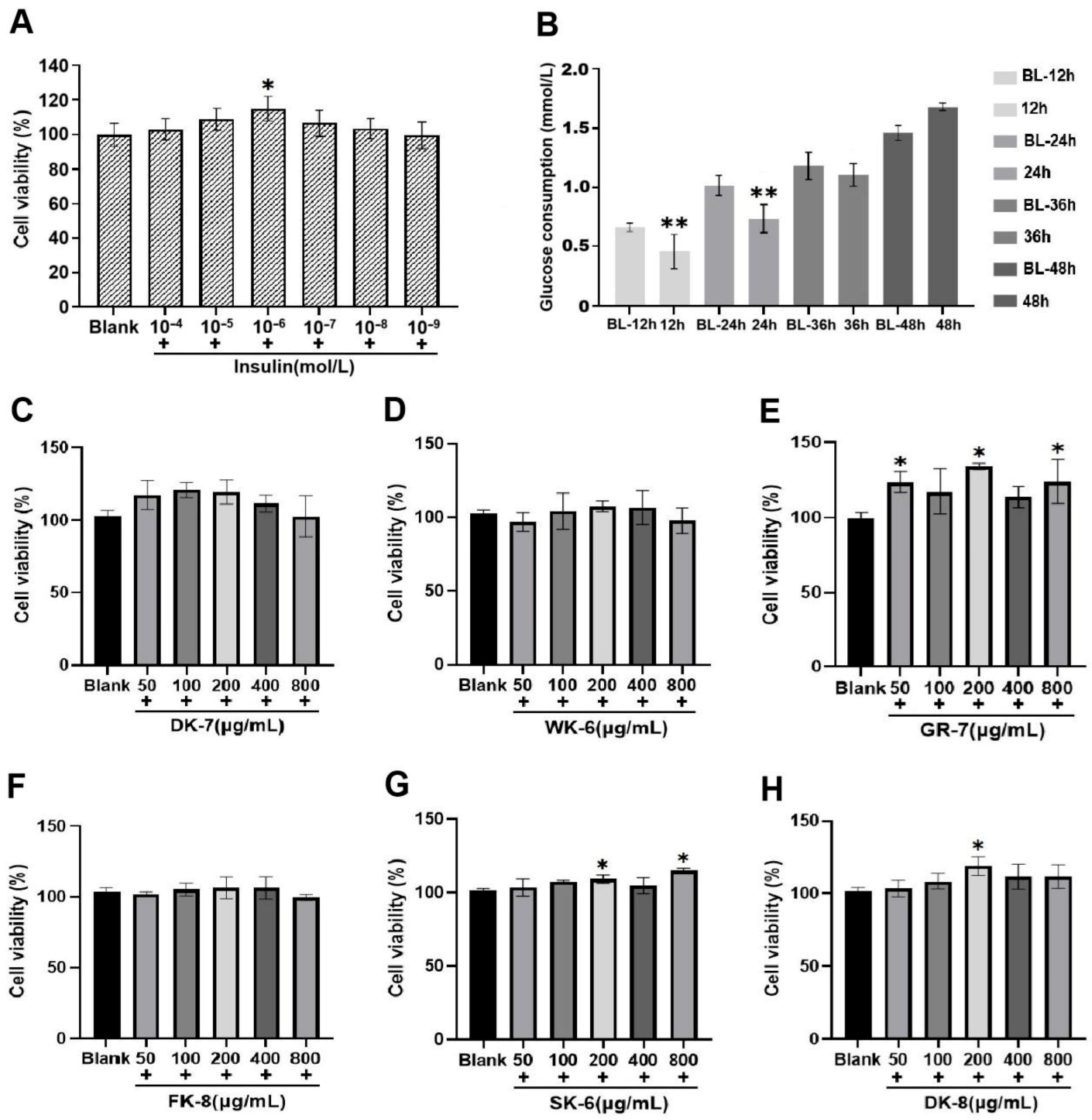

2.7. Effects of Bioactive Peptides on Cell Viability

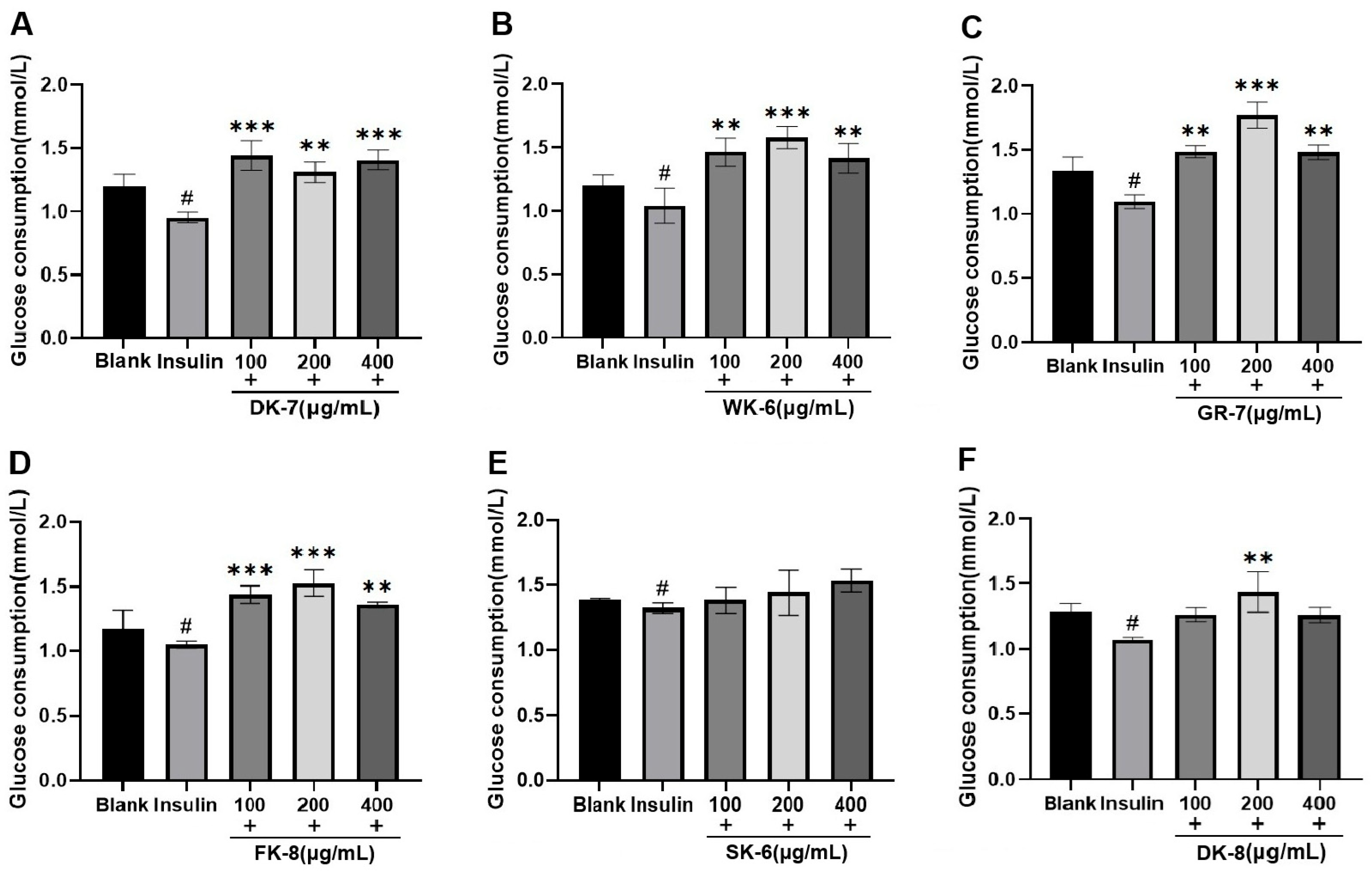

2.8. Effects of Bioactive Peptides on Glucose Consumption in IR-HepG2 Cells

2.9. Molecular Docking Analysis

2.10. Statistics

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. In Silico Screening of Bioactive Peptides from Yellow Mealworm Larvae

3.2. Inhibitory Effects of Six Bioactive Peptides on α-Glucosidase and DPP-IV

3.3. Effects of Six Bioactive Peptides on Glucose Consumption in IR-HepG2 Cell Model

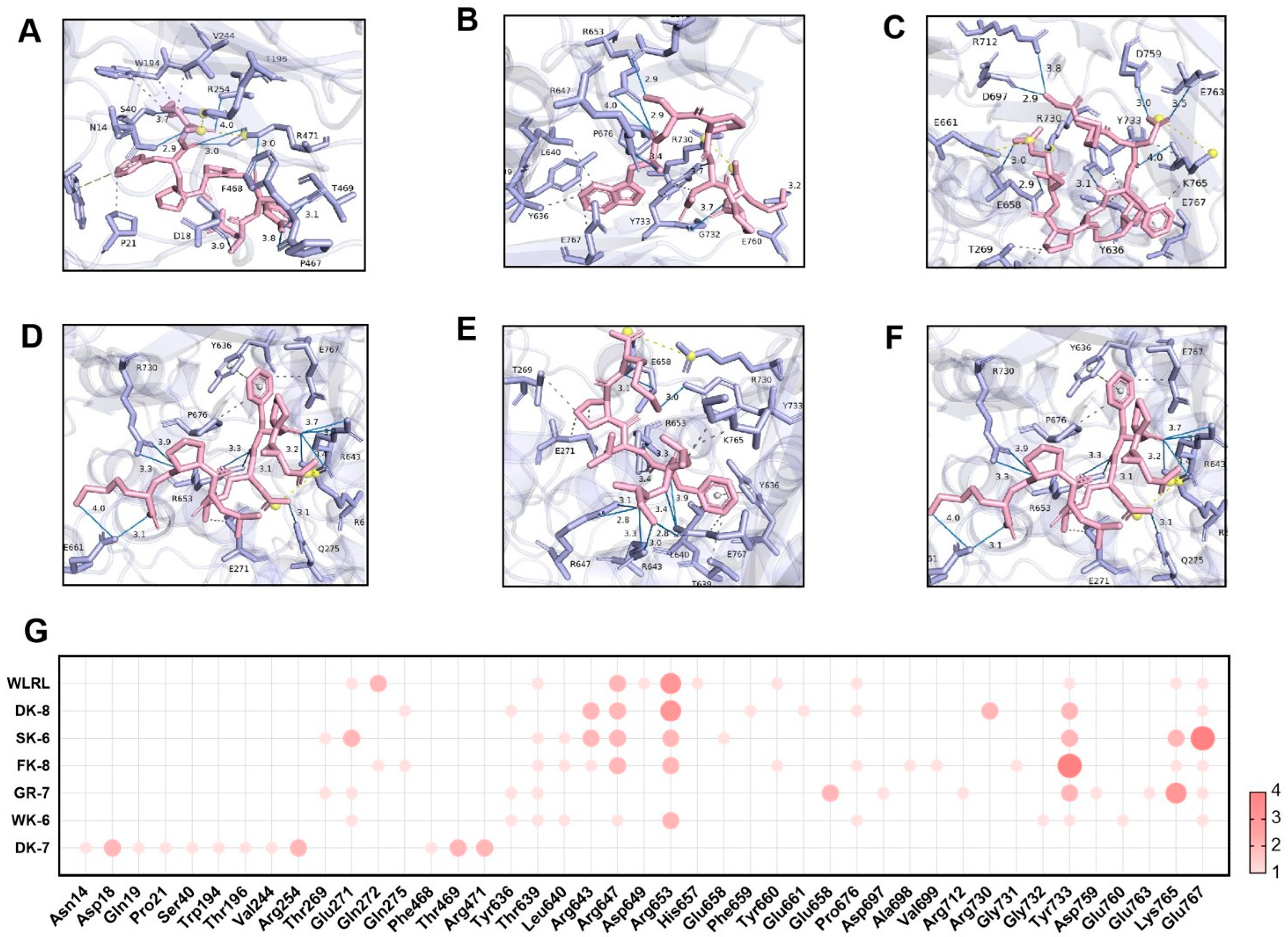

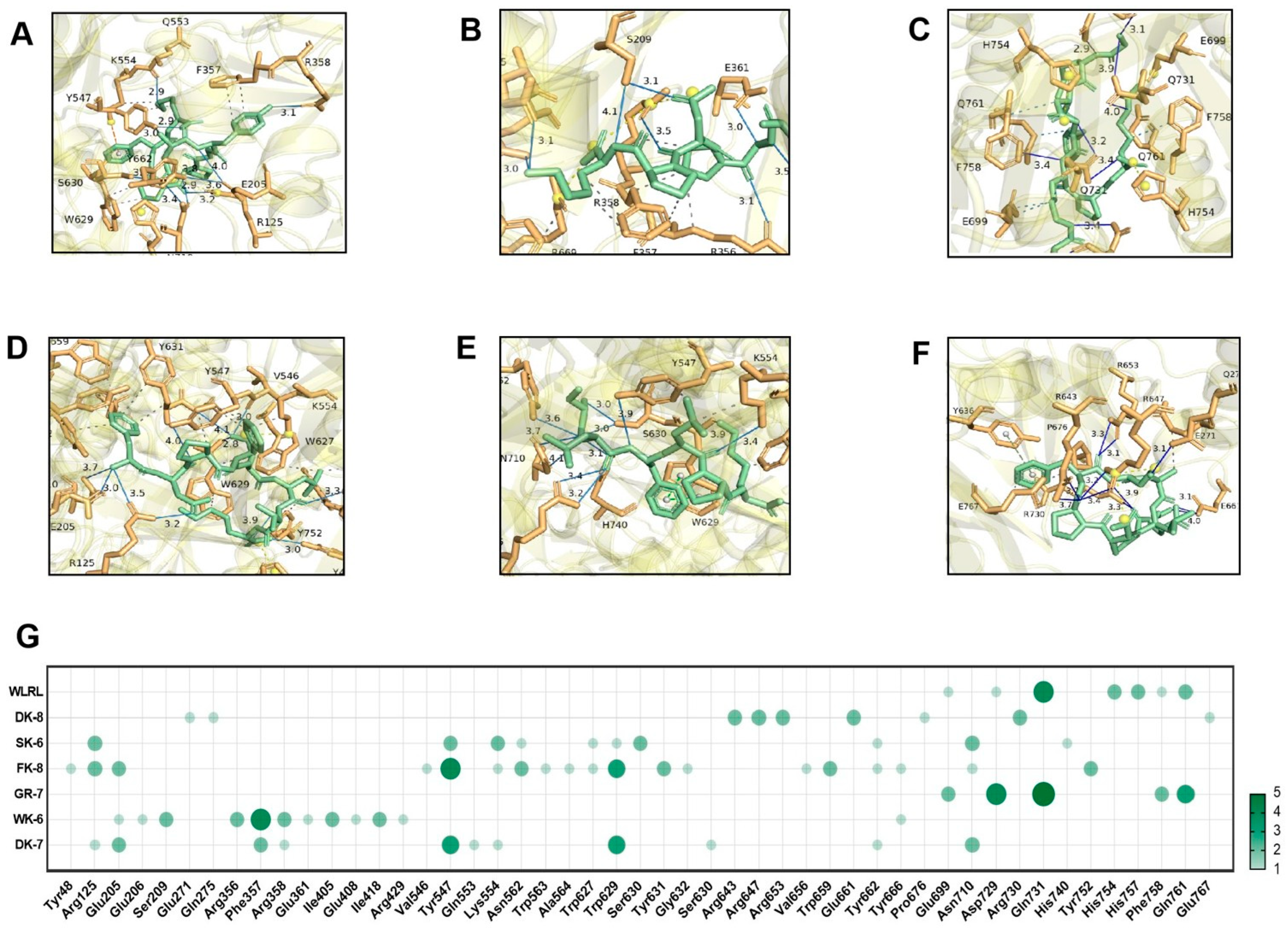

3.4. Molecular Docking Reveals High-Affinity Binding of Six Bioactive Peptides to the Target Enzymes α-Glucosidase and DPP-IV

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Amatya, R.; Park, T.; Hwang, S.; Yang, J.; Lee, Y.; Cheong, H.; Moon, C.; Kwak, H.D.; Min, K.A.; Shin, M.C. Drug Delivery Strategies for Enhancing the Therapeutic Efficacy of Toxin-Derived Anti-Diabetic Peptides. Toxins 2020, 12, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strain, W.D.; Paldánius, P.M. Diabetes, cardiovascular disease and the microcirculation. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2018, 17, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iheagwam, F.N.; Iheagwam, O.T. Diabetes mellitus: The pathophysiology as a canvas for management elucidation and strategies. Med. Nov. Technol. Devices 2025, 25, 100351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matrook, K.A.; Whitford, D.L.; Smith, S.M.; McGilloway, S.; Piyasena, M.P.; Cowman, S. Family-based interventions for adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Prim. Care Diabetes 2025, 19, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, S.; Liu, Q.; Du, Q.; Zeng, X.; Wu, Z.; Pan, D.; Tu, M. Multiple roles of food-derived bioactive peptides in the management of T2DM and commercial solutions: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 279, 134993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lordan, S.; Smyth, T.J.; Soler-Vila, A.; Stanton, C.; Ross, R.P. The α-amylase and α-glucosidase inhibitory effects of Irish seaweed extracts. Food Chem. 2013, 141, 2170–2176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rochín-Medina, J.J.; Ramírez-Serrano, E.S.; Ramírez, K. Inhibition of α-glucosidase activity by potential peptides derived from fermented spent coffee grounds. Food Chem. 2024, 454, 139791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Cheng, J.; Wu, H. Discovery of Food-Derived Dipeptidyl Peptidase IV Inhibitory Peptides: A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhameja, M.; Gupta, P. Synthetic heterocyclic candidates as promising α-glucosidase inhibitors: An overview. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 176, 343–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Beshbishy, H.; Bahashwan, S. Hypoglycemic effect of basil (Ocimum basilicum) aqueous extract is mediated through inhibition of α-glucosidase and α-amylase activities: An in vitro study. Toxicol. Ind. Health 2012, 28, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bo, S.; Dan, M.; Li, W.; Chen, C. The regulatory mechanism of natural polysaccharides in type 2 diabetes mellitus treatment. Drug Discov. Today 2024, 29, 104182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Wu, X.; Yao, X.; Chen, Y.; Ho, C.T.; He, C.; Li, Z.; Wang, Y. Metabolite profiling, antioxidant and α-glucosidase inhibitory activities of buckwheat processed by solid-state fermentation with Eurotium cristatum YL-1. Food Res. Int. 2021, 143, 110262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Bo, N.; Sha, G.; Guan, Y.; Yang, D.; Shan, X.; Lv, Z.; Chen, Q.; Yang, G.; Gong, S.; et al. Identification and molecular mechanism of novel hypoglycemic peptide in ripened pu-erh tea: Molecular docking, dynamic simulation, and cell experiments. Food Res. Int. 2024, 194, 114930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, S.; Yang, L.; Xu, M.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, H. The screening of α-glucosidase inhibitory peptides from β-conglycinin and hypoglycemic mechanism in HepG2 cells and zebrafish larvae. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 278, 134678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivero-Pino, F.; Guadix, A.; Guadix, E.M. Identification of novel dipeptidyl peptidase IV and α-glucosidase inhibitory peptides from Tenebrio molitor. Food Funct. 2021, 12, 873–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adámková, A.; Mlček, J.; Adámek, M.; Borkovcová, M.; Bednářová, M.; Hlobilová, V.; Knížková, I.; Juríková, T. Tenebrio molitor (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae)-Optimization of Rearing Conditions to Obtain Desired Nutritional Values. J. Insect Sci. 2020, 20, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grau, T.; Vilcinskas, A.; Joop, G. Sustainable farming of the mealworm Tenebrio molitor for the production of food and feed. Z Naturforsch C J. Biosci. 2017, 72, 337–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Errico, S.; Spagnoletta, A.; Verardi, A.; Moliterni, S.; Dimatteo, S.; Sangiorgio, P. Tenebrio molitor as a source of interesting natural compounds, their recovery processes, biological effects, and safety aspects. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2022, 21, 148–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quoc, L.P.T. Tenebrio molitor larva: New food applied in medicine and its restrictions. Med. J. Malaysia 2023, 78, 259. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, M.J.; Hawkins, C.L.; Pattison, D.I.; Rees, M.D. Mammalian heme peroxidases: From molecular mechanisms to health implications. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2008, 10, 1199–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Huo, X.; Feng, M.; Fang, Y.; Han, B.; Hu, H.; Wu, F.; Li, J. Proteomics Reveals the Molecular Underpinnings of Stronger Learning and Memory in Eastern Compared to Western Bees. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2018, 17, 255–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, S.; Tao, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Meng, L.; Zhao, L.; Xue, X.; Li, Q.; Wu, L. A Combined Proteomic and Metabolomic Strategy for Allergens Characterization in Natural and Fermented Brassica napus Bee Pollen. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 822033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pal, G.K.; Suresh, P.V. Physico-chemical characteristics and fibril-forming capacity of carp swim bladder collagens and exploration of their potential bioactive peptides by in silico approaches. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 101, 304–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Jia, Y.; Ma, Y.; Cheng, G.; Cai, S. Phenolic Composition, Antioxidant Properties, and Inhibition toward Digestive Enzymes with Molecular Docking Analysis of Different Fractions from Prinsepia utilis Royle Fruits. Molecules 2018, 23, 3373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Liang, X.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, Z.; Xue, X.; Wang, K.; Wu, L. UPLC-Q-Exactive Orbitrap/MS-Based Lipidomics Approach To Characterize Lipid Extracts from Bee Pollen and Their in Vitro Anti-Inflammatory Properties. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65, 6848–6860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, G.Y.; Hou, L.K.; Guo, J.H.; Sun, J.C.; Nong, Q.; Wang, Y.F.; Hu, S.W.; Zhao, W.J.; Tan, J.; Liu, X.F.; et al. The structures of two polysaccharides from Fructus Corni and their protective effect on insulin resistance. Carbohydr. Polym. 2025, 353, 123290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Zhao, Q.; Xie, J.; Sun, D. Polysaccharides from pineapple pomace: New insight into ultrasonic-cellulase synergistic extraction and hypoglycemic activities. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 121, 1213–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, M.; Zuccollo, A.; Hou, X.; Nagata, D.; Walsh, K.; Herscovitz, H.; Brecher, P.; Ruderman, N.B.; Cohen, R.A. AMP-activated protein kinase is required for the lipid-lowering effect of metformin in insulin-resistant human HepG2 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 47898–47905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trott, O.; Olson, A.J. AutoDock Vina: Improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 2010, 31, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, G.; Peng, X.; Dong, D.; Nian, Y.; Gao, Y.; Wang, X.; Hong, D.; Qiu, M. New ent-kaurane diterpenes from the roasted arabica coffee beans and molecular docking to α-glucosidase. Food Chem. 2021, 345, 128823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mooney, C.; Haslam, N.J.; Pollastri, G.; Shields, D.C. Towards the improved discovery and design of functional peptides: Common features of diverse classes permit generalized prediction of bioactivity. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e45012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, H.; Wu, X.; Pan, J.; Hu, X.; Gong, D.; Zhang, G. New Insights into the Inhibition Mechanism of Betulinic Acid on α-Glucosidase. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 7065–7075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, G.; Xu, Y.; Li, J.; Li, K.; Xu, X.; Gao, X.; Zhao, Y.; Jiang, H.; Mao, X. Hypoglycemic peptide preparation from Bacillus subtilis fermented with Pyropia: Identification, molecular docking, and in vivo confirmation. Food Chem. 2025, 463, 141096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li-Chan, E.C.; Hunag, S.L.; Jao, C.L.; Ho, K.P.; Hsu, K.C. Peptides derived from atlantic salmon skin gelatin as dipeptidyl-peptidase IV inhibitors. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 973–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muoio, D.M.; Newgard, C.B. Mechanisms of disease: Molecular and metabolic mechanisms of insulin resistance and beta-cell failure in type 2 diabetes. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008, 9, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Teng, H.; Cao, H. Chlorogenic acid and caffeic acid from Sonchus oleraceus Linn synergistically attenuate insulin resistance and modulate glucose uptake in HepG2 cells. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2019, 127, 182–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wu, T.; Fang, L.; Liu, C.; Liu, X.; Li, H.; Shi, J.; Li, M.; Min, W. Anti-diabetic effect by walnut (Juglans mandshurica Maxim.)-derived peptide LPLLR through inhibiting α-glucosidase and α-amylase, and alleviating insulin resistance of hepatic HepG2 cells. J. Funct. Foods 2020, 69, 103944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Zheng, X.; Zhao, L.; Cai, S. Identification of novel peptides in distillers’ grains as antioxidants, α-Glucosidase inhibitors, and insulin sensitizers: In silico and in vitro evaluation. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derosa, G.; Maffioli, P.; D’Angelo, A.; Di Pierro, F. A role for quercetin in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Phytother. Res. 2021, 35, 1230–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Zhao, H.; Pan, X.; Orfila, C.; Lu, W.; Ma, Y. Preparation of bioactive peptides with antidiabetic, antihypertensive, and antioxidant activities and identification of α-glucosidase inhibitory peptides from soy protein. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 7, 1848–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Wang, H.; Zhang, F.; Guo, S.; Shen, Q. Comparison of the generation of α-glucosidase inhibitory peptides derived from prolamins of raw and cooked foxtail millet: In vitro activity, de novo sequencing, and in silico docking. Food Chem. 2023, 411, 135378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Chi, H.; Ma, S.; Zhao, L.; Cai, S. Identification of novel α-glucosidase inhibitory peptides in rice wine and their antioxidant activities using in silico and in vitro analyses. LWT 2023, 178, 114629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roig-Zamboni, V.; Cobucci-Ponzano, B.; Iacono, R.; Ferrara, M.C.; Germany, S.; Bourne, Y.; Parenti, G.; Moracci, M.; Sulzenbacher, G. Structure of human lysosomal acid α-glucosidase-a guide for the treatment of Pompe disease. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Z.W.; Chen, C.H.; Ke, J.P.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Qi, Y.; Liu, S.Y.; Yang, Z.; Ning, J.M.; Bao, G.H. α-Glucosidase Inhibitory Activities and the Interaction Mechanism of Novel Spiro-Flavoalkaloids from YingDe Green Tea. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 136–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szablewski, L. Changes in Cells Associated with Insulin Resistance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 2397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.H.; Park, S.Y.; Choi, C.S. Insulin Resistance: From Mechanisms to Therapeutic Strategies. Diabetes Metab. J. 2022, 46, 15–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Peptide Sequence | Abbreviation | Retention Time (min) | Mass (Da) | m/z | Peptide Ranker Score a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DYGPPFK | DK-7 | 33.64 | 822.3912 | 412.2027 | 0.8825 |

| WSPDPK | WK-6 | 10.80 | 728.3493 | 365.1817 | 0.8460 |

| GMDFQPR | GR-7 | 21.99 | 849.3803 | 425.6973 | 0.8088 |

| FNPFDLTK | FK-8 | 53.35 | 980.4967 | 491.2564 | 0.7960 |

| SLFLPK | SK-6 | 31.50 | 703.4268 | 352.7203 | 0.7952 |

| DPFDALPK | DK-8 | 44.05 | 901.4545 | 451.7343 | 0.7904 |

| Enzymes | Peptides | Standard Curves | R2 | Linearity Ranges (mg/mL) | IC50 (mg/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α-Glucosidase | DK-7 | Y = 9.93 × 10−5 × X − 0.0722 | 0.9995 | 1–10 | 5.76 |

| WK-6 | Y = 7.39 × 10−5 × X − 0.0782 | 0.9930 | 1–10 | 7.82 | |

| GR-7 | Y = 8.46 × 10−5 × X − 0.0356 | 0.9991 | 1–10 | 6.17 | |

| FK-8 | Y = 0.0458 × X − 0.0064 | 0.9949 | 1–12 | 11.06 | |

| SK-6 | Y = 5.27 × 10−5 × X − 0.0340 | 0.9953 | 1–10 | 10.14 | |

| DK-8 | Y = 1.03 × 10−4 × X − 0.0977 | 0.9968 | 1–10 | 5.58 | |

| DPP-IV | DK-7 | Y = 2 × 10−5 × X + 0.0297 | 0.9927 | 1–5 | - |

| WK-6 | Y = 3 × 10−5 × X + 0.2241 | 0.9928 | 1–10 | 9.20 | |

| GR-7 | Y = 8 × 10−4 × X − 0.0127 | 0.9983 | 0.1-1 | 0.64 | |

| FK-8 | Y = 1 × 10−5 × X + 0.0037 | 0.9959 | 1–10 | - | |

| SK-6 | Y = 1 × 10−5 × X + 0.0142 | 0.9990 | 1–10 | - | |

| DK-8 | Y = 5 × 10−5 × X + 0.1033 | 0.9925 | 1–10 | 7.93 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhu, Y.; Zhou, E.; Tang, Y.; Li, Q.; Wu, L. Edible Yellow Mealworm-Derived Antidiabetic Peptides: Dual Modulation of α-Glucosidase and Dipeptidyl-Peptidase IV Inhibition Revealed by Integrated Proteomics, Bioassays, and Molecular Docking Analysis. Foods 2026, 15, 96. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010096

Zhu Y, Zhou E, Tang Y, Li Q, Wu L. Edible Yellow Mealworm-Derived Antidiabetic Peptides: Dual Modulation of α-Glucosidase and Dipeptidyl-Peptidase IV Inhibition Revealed by Integrated Proteomics, Bioassays, and Molecular Docking Analysis. Foods. 2026; 15(1):96. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010096

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhu, Yuying, Enning Zhou, Yingran Tang, Qiangqiang Li, and Liming Wu. 2026. "Edible Yellow Mealworm-Derived Antidiabetic Peptides: Dual Modulation of α-Glucosidase and Dipeptidyl-Peptidase IV Inhibition Revealed by Integrated Proteomics, Bioassays, and Molecular Docking Analysis" Foods 15, no. 1: 96. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010096

APA StyleZhu, Y., Zhou, E., Tang, Y., Li, Q., & Wu, L. (2026). Edible Yellow Mealworm-Derived Antidiabetic Peptides: Dual Modulation of α-Glucosidase and Dipeptidyl-Peptidase IV Inhibition Revealed by Integrated Proteomics, Bioassays, and Molecular Docking Analysis. Foods, 15(1), 96. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010096