Dipeptidyl Peptidase-4 Inhibitory Activity of Buckwheat Flour-Derived Peptides and Oral Glucose Tolerance Test of Buckwheat Flour Hydrolysates in Rats

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Assay for DPP-4 Inhibitory Activity

2.2. Preparation of Buckwheat Flour Hydrolysate

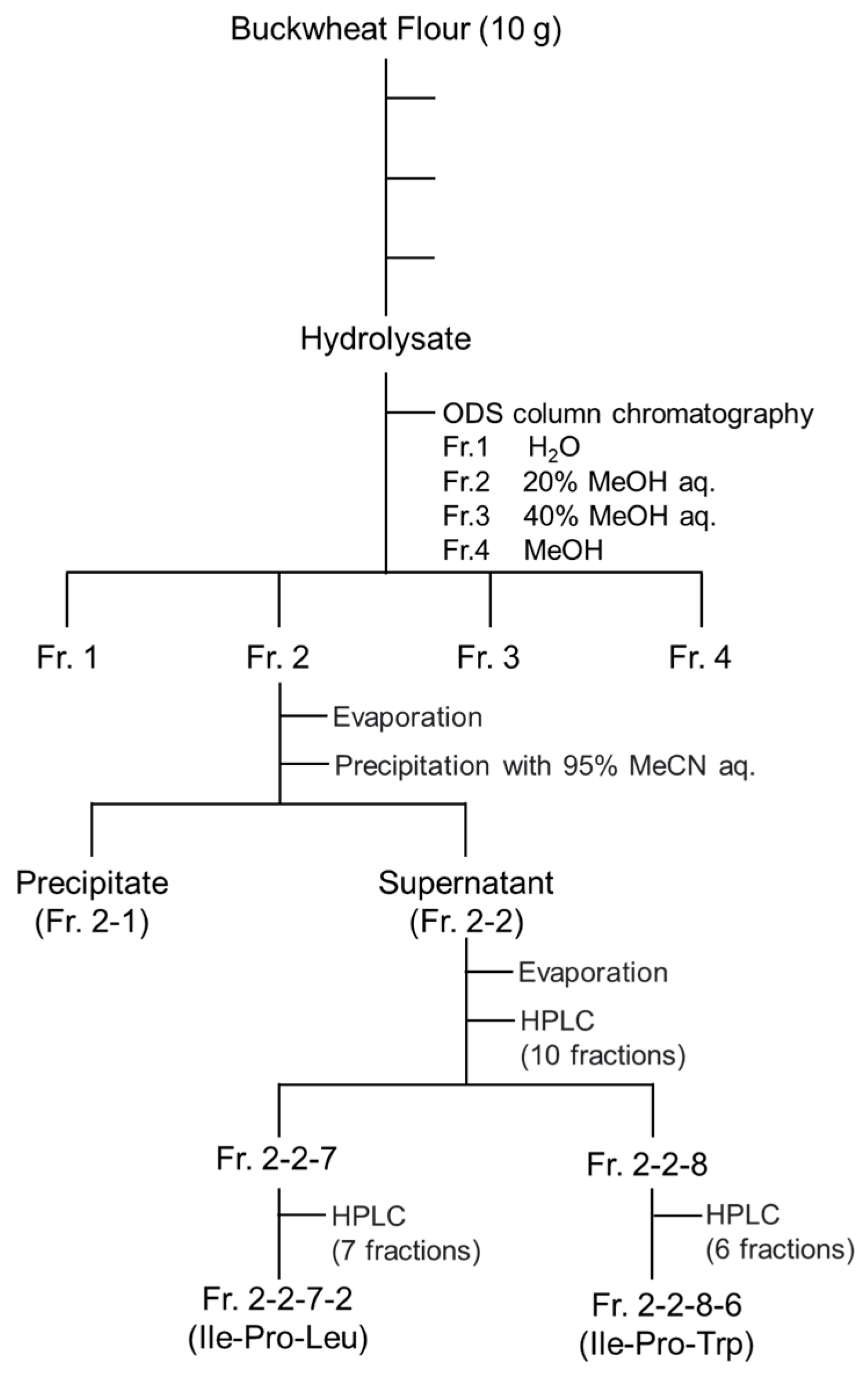

2.3. Purification of Buckwheat Flour Hydrolysate

2.4. Identification of DPP-4 Inhibitory Peptides Using LC–MS/MS Analysis

2.5. Determination of Amino Acid Sequences of Active Peptides Using LC-MS/MS

2.6. Evaluation of DPP-4 Inhibitory Activities of Fr. 2-2, Ile-Pro-Leu, and Ile-Pro-Trp After In Vitro Digestion

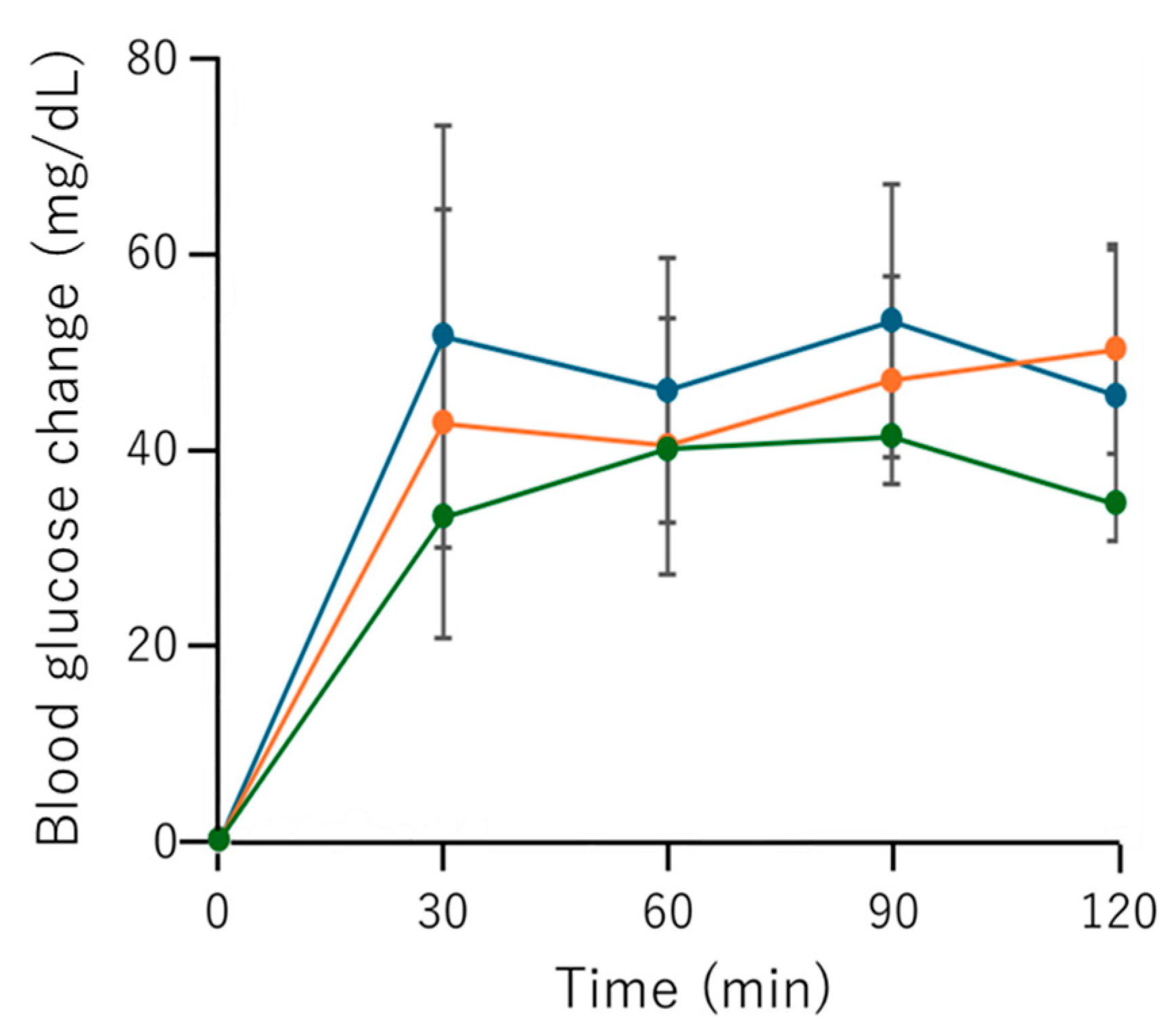

2.7. Oral Glucose Tolerance Test (OGTT) Using DPP-4 Inhibitory Fr. 2 in Rats

2.8. Standard Peptides

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. DPP-4 Inhibitory Activity of Buckwheat Flour Hydrolysate

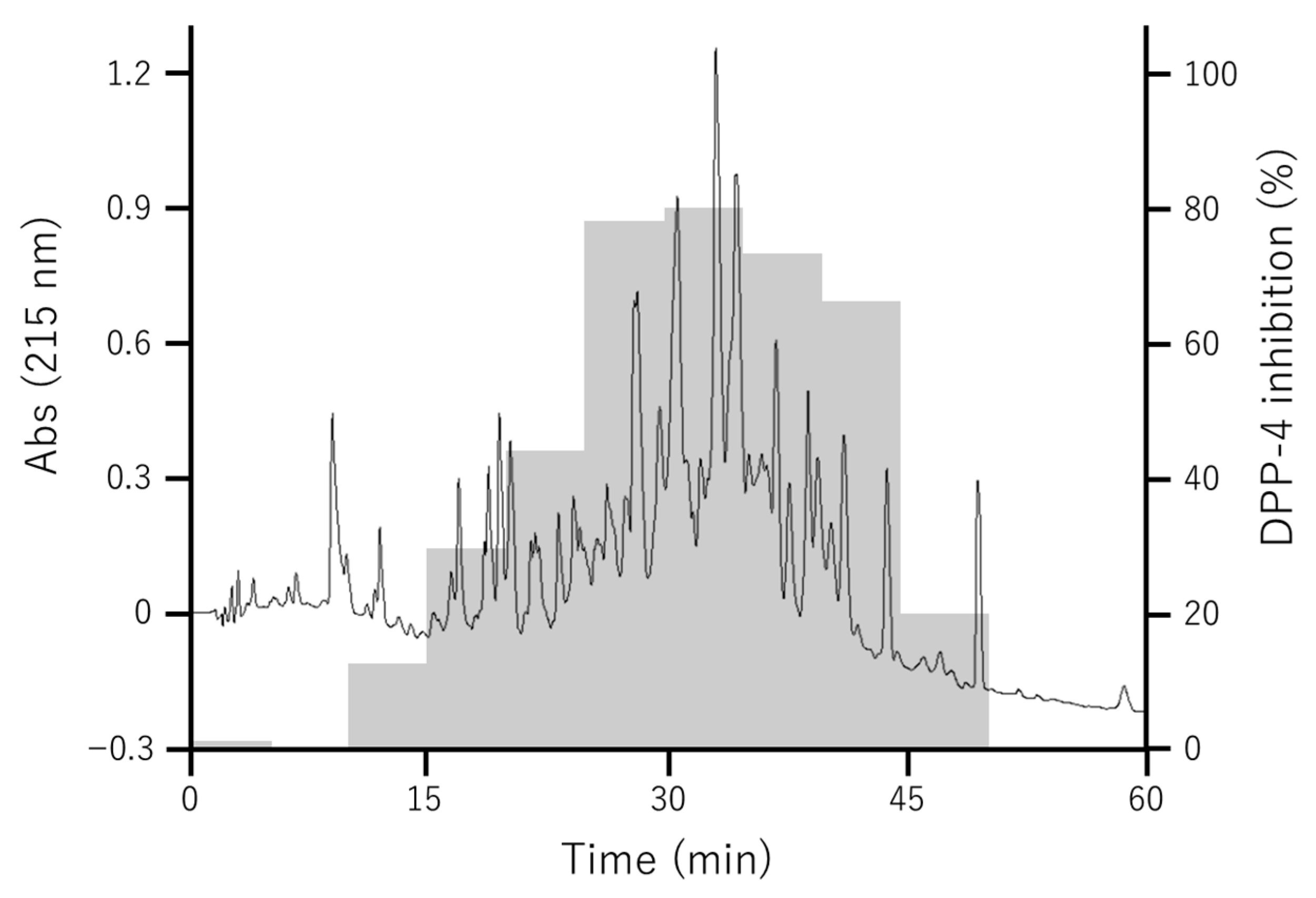

3.2. Separation of DPP-4 Inhibitory Peptides in Fr. 2

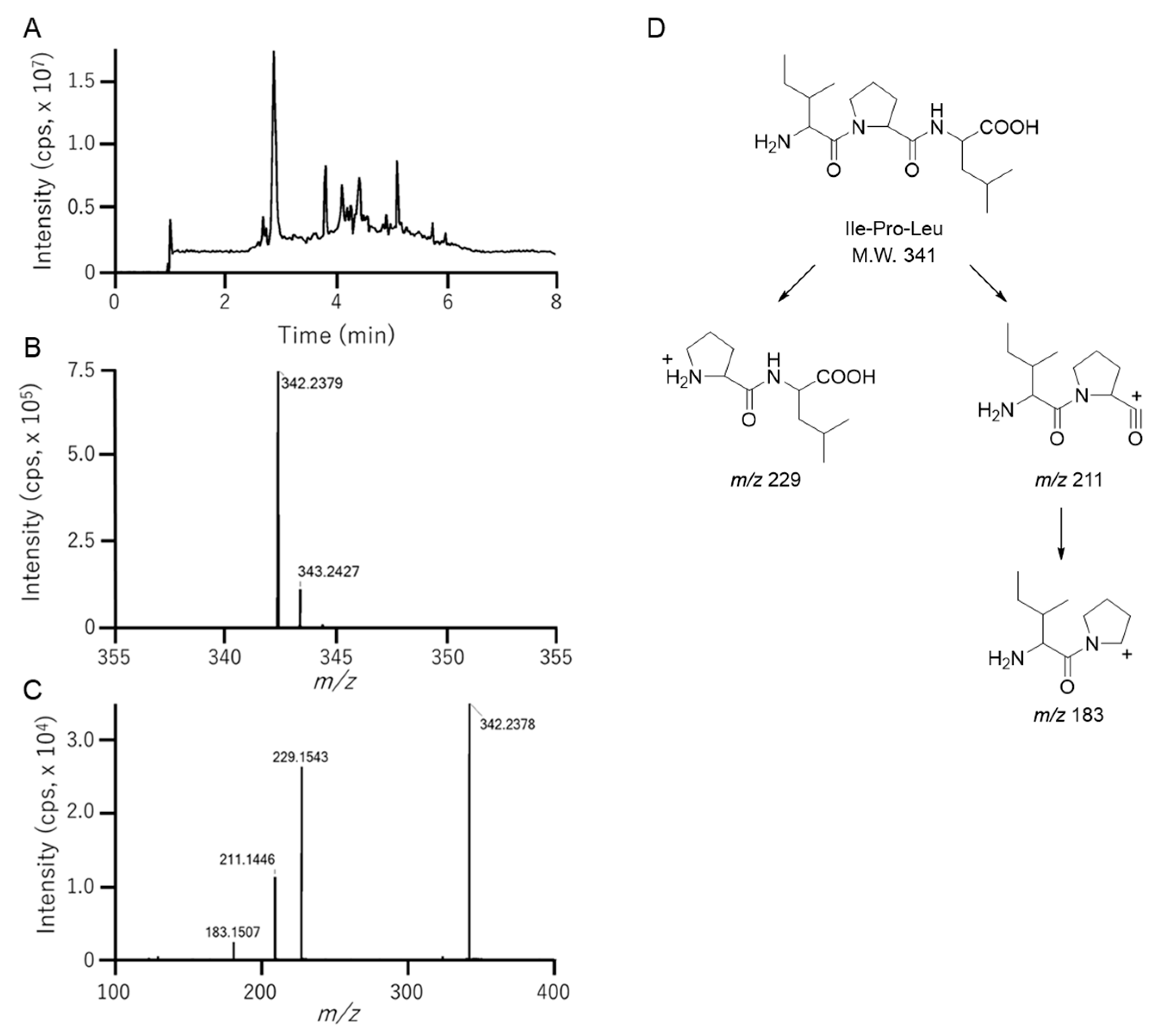

3.3. Identification of Ile-Pro-Leu in Fr. 2-2-7-2

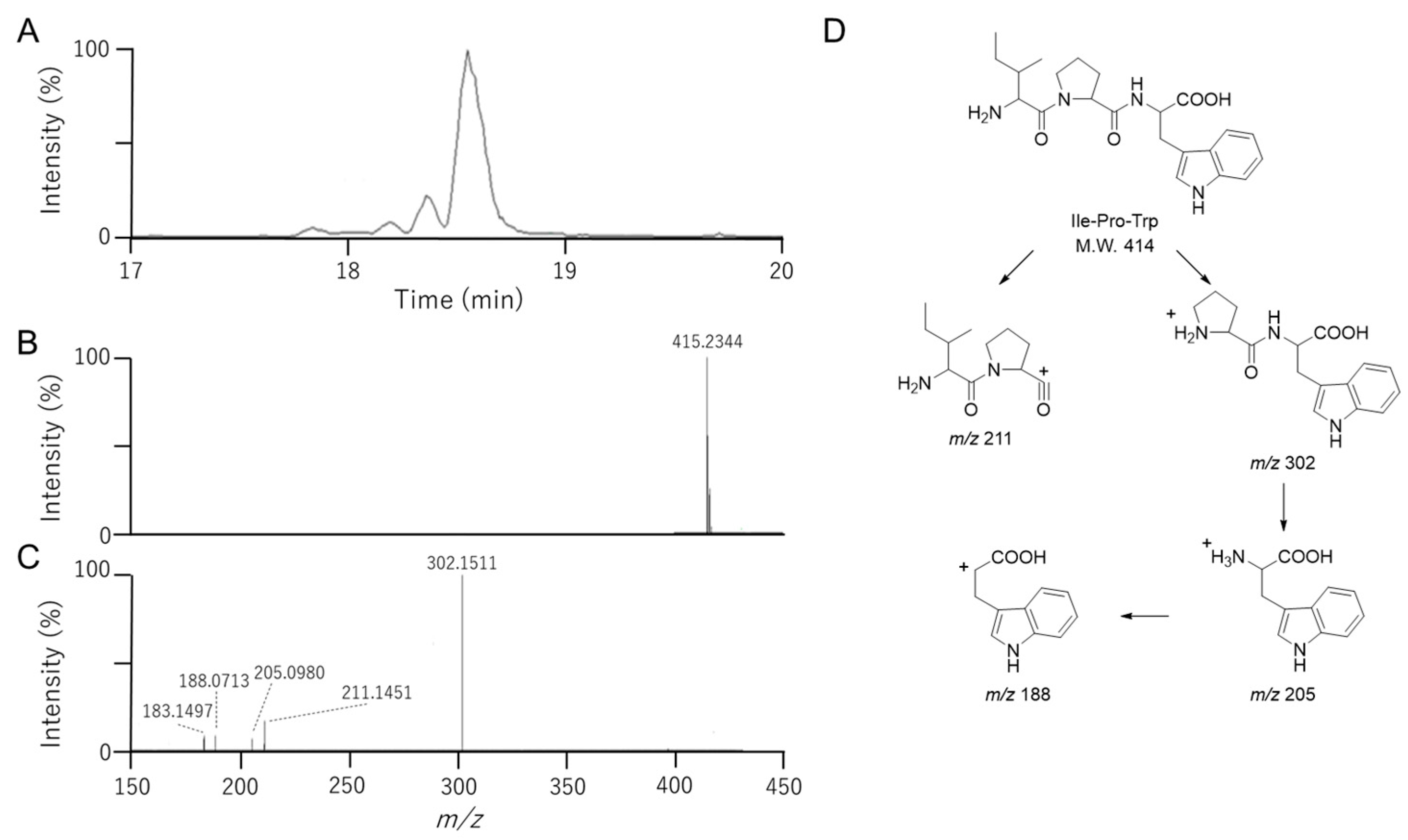

3.4. Identification of Ile-Pro-Trp in Fr. 2-2-8-6

3.5. In Vitro Digestion of Peptides, Fr. 2, Ile-Pro-Leu and Ile-Pro-Trp

3.6. OGTT Using DPP-4 Inhibitory Fr. 2 in Rats

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Duncan, B.B.; Magliano, D.J.; Boyko, E.J. IDF Diabetes Atlas 11th edition 2025: Global prevalence and projections for 2050. Nephrol. Dial. Transpl. 2025, gfaf177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulvihill, E.E.; Drucker, D.J. Pharmacology, physiology, and mechanisms of action of dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors. Front. Endocrinol. 2019, 10, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallwitz, B. DPP-4 inhibitors and their potential role in the management of type 2 diabetes. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2007, 61, 1215–1224. [Google Scholar]

- González-Osuna, M.F.; Bernal-Mercado, A.T.; Wong-Corral, F.J.; Ezquerra-Brauer, J.M.; Soto-Valdez, H.; Castillo, A.; Rodríguez-Figueroa, J.C.; Del-Toro-Sánchez, C.L. Bioactive peptides and protein hydrolysates used in meat and meat products’ preservation—A review. ACS Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 4, 1003–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsui, T.; Matsufuji, H.; Seki, E.; Osajima, K.; Nakashima, M.; Osajima, Y. Inhibition of angiotensin I-converting enzyme by Bacillus licheniformis alkaline protease hydrolyzates derived from sardine muscle. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 1993, 57, 922–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsufuji, H.; Matsui, T.; Seki, E.; Osajima, K.; Nakashima, M.; Osajima, Y. Angiotensin I-converting enzyme inhibitory peptides in an alkaline protease hydrolyzate derived from sardine muscle. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 1994, 58, 2244–2245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otani, L.; Ninomiya, T.; Murakami, M.; Osajima, K.; Kato, H.; Murakami, T. Sardine peptide with angiotensin I-converting enzyme inhibitory activity improves glucose tolerance in stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rats. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2009, 73, 2203–2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safitri, E.; Kuziel, O.H.; Nagai, T.; Saito, M. Characterization of collagen and its hydrolysate from southern bluefin tuna skin and their potencies as DPP-IV inhibitors. Food Chem. Adv. 2024, 5, 100774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.; Zhang, L.; Song, W.; Zhang, C.; Hua, Y.; Chen, Y.; Li, X. Separation, identification and molecular binding mechanism of dipeptidyl peptidase IV inhibitory peptides derived from walnut (Juglans regia L.) protein. Food Chem. 2021, 347, 129062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nongonierma, A.B.; FitzGerald, R.J. In silico approaches to predict the potential of milk protein-derived peptides as dipeptidyl peptidase IV (DPP-IV) inhibitors. Peptides 2014, 57, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, A.; Khalid, N.; Ahmad, A.; Abbasi, N.A.; Latif, M.S.Z.; Randhawa, M.A. Phytochemicals and biofunctional properties of buckwheat: A review. J. Agric. Sci. 2014, 152, 349–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonafaccia, G.; Marocchini, M.; Kreft, I. Composition and technological properties of the flour and bran from common and tartary buckwheat. Food Chem. 2003, 80, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christa, K.; Soral-Śmietana, M. Buckwheat grains and buckwheat products—Nutritional and prophylactic value of their components—Review. Czech J. Food Sci. 2008, 26, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziadek, K.; Kopeć, A.; Pastucha, E.; Piątkowska, E.; Leszczyńska, T.; Pisulewska, E.; Witkowicz, R.; Francik, R. Basic chemical composition and bioactive compounds content in selected cultivars of buckwheat whole seeds, dehulled seeds and hulls. J. Cereal Sci. 2016, 69, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.X.; Zou, L.; Tan, M.L.; Deng, Y.Y.; Yan, J.; Yan, Z.Y.; Zhao, G. Free amino acids, fatty acids, and phenolic compounds in tartary buckwheat of different hull colour. Czech J. Food Sci. 2017, 35, 214–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, K.; Miyasaka, S.; Tsuji, A.; Tachi, H. Isolation and characterization of peptides with dipeptidyl peptidase IV (DPPIV) inhibitory activity from natto using DPPIV from Aspergillus oryzae. Food Chem. 2018, 261, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, Y.; Kamata, A.; Konishi, T. Dipeptidyl peptidase-IV inhibitory peptides derived from salmon milt and their effects on postprandial blood glucose level. Fish. Sci. 2021, 87, 619–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araki, M.; Kanegawa, N.; Iwata, H.; Sagae, Y.; Ito, K.; Masuda, K.; Okuno, Y. Hydrophobic interactions at subsite S1′ of human dipeptidyl peptidase IV contribute significantly to the inhibitory effect of tripeptides. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Fraction | Weight (g) | DPP-4 Inhibition (%, 10 mg/mL) | IC50 (mg/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fr. 1 | 4.915 | 17.0 ± 1.65 | n.d. |

| Fr. 2 | 0.193 | 91.5 ± 1.8 | 1.67 ± 0.11 |

| Fr. 3 | 0.049 | 90.3 ± 3.9 | 2.14 ± 0.08 |

| Fr. 4 | 0.042 | 41.6 ± 10.1 | n.d. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Mitsui, N.; Shiono, K.; Seto, Y.; Furusho, T.; Saito, C.; Takahashi, K. Dipeptidyl Peptidase-4 Inhibitory Activity of Buckwheat Flour-Derived Peptides and Oral Glucose Tolerance Test of Buckwheat Flour Hydrolysates in Rats. Foods 2026, 15, 92. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010092

Mitsui N, Shiono K, Seto Y, Furusho T, Saito C, Takahashi K. Dipeptidyl Peptidase-4 Inhibitory Activity of Buckwheat Flour-Derived Peptides and Oral Glucose Tolerance Test of Buckwheat Flour Hydrolysates in Rats. Foods. 2026; 15(1):92. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010092

Chicago/Turabian StyleMitsui, Noe, Kouji Shiono, Yoshiya Seto, Tadasu Furusho, Chika Saito, and Kosaku Takahashi. 2026. "Dipeptidyl Peptidase-4 Inhibitory Activity of Buckwheat Flour-Derived Peptides and Oral Glucose Tolerance Test of Buckwheat Flour Hydrolysates in Rats" Foods 15, no. 1: 92. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010092

APA StyleMitsui, N., Shiono, K., Seto, Y., Furusho, T., Saito, C., & Takahashi, K. (2026). Dipeptidyl Peptidase-4 Inhibitory Activity of Buckwheat Flour-Derived Peptides and Oral Glucose Tolerance Test of Buckwheat Flour Hydrolysates in Rats. Foods, 15(1), 92. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010092