Screening of Lactic Acid Bacteria and RSM-Based Optimization for Enhancing γ-Aminobutyric Acid (GABA) Accumulation in Orange Juice

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Starter Preparation

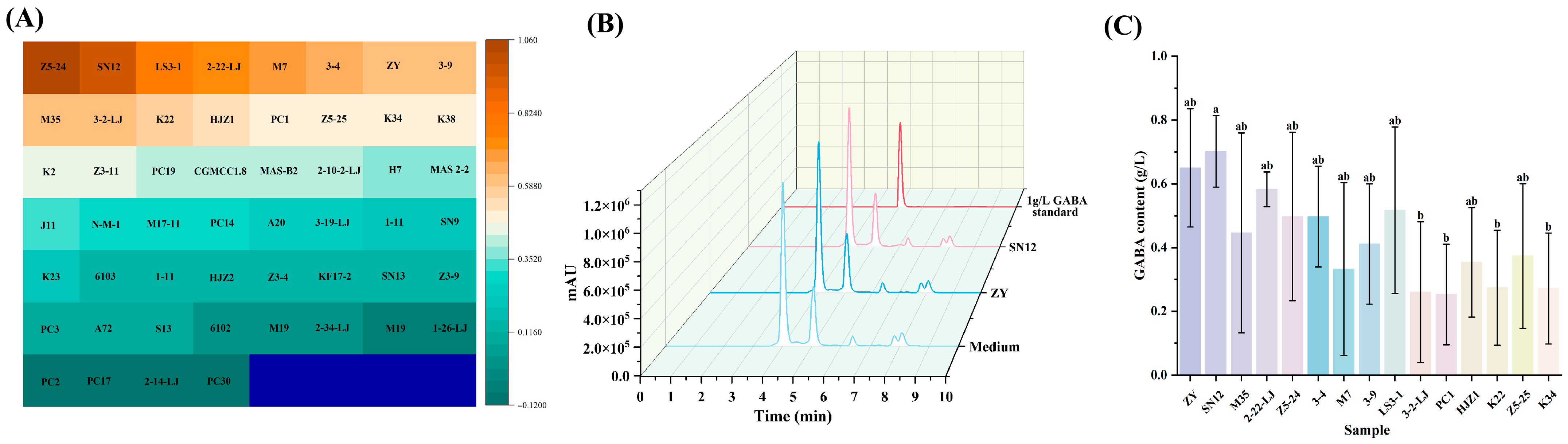

2.2. GABA-Producing LAB Screening

2.2.1. Rapid Screening of GABA by Berthelot Colorimetric Method

2.2.2. Quantitative Screening of GABA by HPLC

2.3. Evaluation of LAB Fermentation Performance and Probiotic Properties

2.4. Evaluation of Substrate Adaptation

2.5. Preparation of Fermented Orange Juice

2.6. Design of Single-Factor Experiment

2.7. Design of RSM

2.7.1. Plackett–Burman Design

2.7.2. Box–Behnken Design

2.8. Model Validation

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Analysis of GABA-Producing LAB

3.2. Analysis of Fermentation Performers and Probiotic Properties

3.3. LAB Adaptability Evaluation in Orange Juice

3.4. Analysis of Single-Factor Experiment

3.4.1. pH

3.4.2. Fermentation Temperature

3.4.3. Soluble Solids Content

3.4.4. Inoculum Ratio

3.4.5. Inoculum Size

3.4.6. Fermentation Time

3.5. Optimization of GABA Content in Orange Juice Using RSM

3.5.1. Analysis of Plackett–Burman Design

3.5.2. Analysis of Box–Behnken Design

3.6. Effect of Optimal Fermentation Conditions on GABA Content in Orange Juice

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Number | Strain Name | Isolation Source | Acquisition Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Lacticaseibacillus paracasei ZY | Fermented milk | Laboratory isolation |

| 2 | Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus SN12 | Fermented milk | Laboratory isolation |

| 3 | Lactiplantibacillus plantarum M35 | Fermented meat | Laboratory isolation |

| 4 | Lactiplantibacillus plantarum 2-22-LJ | Fermented meat | Laboratory isolation |

| 5 | Lactiplantibacillus plantarum Z5-24 | Fermented meat | Laboratory isolation |

| 6 | Lacticaseibacillus paracasei 3-4 | Fermented meat | Laboratory isolation |

| 7 | Lactiplantibacillus plantarum M7 | Fermented meat | Laboratory isolation |

| 8 | Lacticaseibacillus paracasei 3-9 | Fermented meat | Laboratory isolation |

| 9 | Lactiplantibacillus plantarum LS3-1 | Fermented pickles | Laboratory isolation |

| 10 | Lactiplantibacillus plantarum 3-2-LJ | Fermented meat | Laboratory isolation |

| 11 | Limosilactobacillus reuteri PC1 | Fermented pickles | Laboratory isolation |

| 12 | Lactiplantibacillus plantarum HJZ1 | Distiller’s grains | Laboratory isolation |

| 13 | Lacticaseibacillus paracasei K22 | Fermented milk | Laboratory isolation |

| 14 | Lactiplantibacillus plantarum Z5-25 | Fermented meat | Laboratory isolation |

| 15 | Lacticaseibacillus casei K34 | Fermented milk | Laboratory isolation |

| 16 | Lacticaseibacillus paracasei K38 | Fermented milk | Laboratory isolation |

| 17 | Pediococcus acidilactici K2 | Fermented meat | Laboratory isolation |

| 18 | Lactiplantibacillus plantarum 3-19-LJ | Fermented meat | Laboratory isolation |

| 19 | Lacticaseibacillus paracasei MAS-B2 | Fermented milk | Laboratory isolation |

| 20 | Pediococcus pentosaceus 2-10-2-LJ | Fermented meat | Laboratory isolation |

| 21 | Limosilactobacillus fermentum CGMCC1.8 | —— | Obtained from CGMCC |

| 22 | Lactiplantibacillus plantarum J11 | Fermented meat | Laboratory isolation |

| 23 | Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus H7 | Fermented meat | Laboratory isolation |

| 24 | Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis MAS2-2 | Fermented meat | Laboratory isolation |

| 25 | Lactiplantibacillus plantarum 1-26-LJ | Fermented meat | Laboratory isolation |

| 26 | Lactiplantibacillus plantarum N-M-1 | Fermented milk | Laboratory isolation |

| 27 | Latilactobacillus sakei PC19 | Fermented pickles | Laboratory isolation |

| 28 | Lactiplantibacillus plantarum PC14 | Fermented pickles | Laboratory isolation |

| 29 | Lactobacillus acidophilus A20 | Fermented meat | Laboratory isolation |

| 30 | Lacticaseibacillus paracasei Z3-11 | Fermented meat | Laboratory isolation |

| 31 | Lactiplantibacillus plantarum 1-1 | Fermented milk | Laboratory isolation |

| 32 | Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus SN9 | Fermented pickles | Laboratory isolation |

| 33 | Streptococcus salivarius subsp.thermophilus M17-11 | Fermented milk | Laboratory isolation |

| 34 | Lactiplantibacillus plantarum 2-14-LJ | Fermented meat | Laboratory isolation |

| 35 | Lactiplantibacillus plantarum 1-11 | Fermented milk | Laboratory isolation |

| 36 | Pediococcus pentosaceus HJZ2 | Distiller’s grains | Laboratory isolation |

| 37 | Lactiplantibacillus plantarum M19 | Fermented meat | Laboratory isolation |

| 38 | Streptococcus salivarius subsp. thermophilus KF17-2 | —— | Obtained from CICC |

| 39 | Latilactobacillus sakei S13 | Fermented milk | Laboratory isolation |

| 40 | Lacticaseibacillus paracasei Z3-9 | Fermented meat | Laboratory isolation |

| 41 | Lacticaseibacillus paracasei K23 | Fermented milk | Laboratory isolation |

| 42 | Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp.bulgaricus 6103 | —— | Obtained from CICC |

| 43 | Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus SN13 | Fermented pickles | Laboratory isolation |

| 44 | Lactobacillus helveticus 6102 | —— | Obtained from CICC |

| 45 | Lacticaseibacillus paracasei Z3-4 | Fermented meat | Laboratory isolation |

| 46 | Limosilactobacillus fermentum 2-34-LJ | Fermented meat | Laboratory isolation |

| 47 | Lactobacillus acidophilus LS2-3 | Fermented pickles | Laboratory isolation |

| 48 | Lactiplantibacillus plantarum A72 | Fermented pickles | Laboratory isolation |

| 49 | Latilactobacillus sakei PC2 | Fermented pickles | Laboratory isolation |

| 50 | Latilactobacillus sakei PC3 | Fermented pickles | Laboratory isolation |

| 51 | Latilactobacillus sakei PC17 | Fermented pickles | Laboratory isolation |

| 52 | Latilactobacillus sakei PC30 | Fermented pickles | Laboratory isolation |

| Factors | Unit | Levels | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial pH | — | 3.0 | 4.0 | 5.0 | 6.0 | 7.0 |

| Fermentation temperature | °C | 27 | 32 | 37 | 42 | 47 |

| Soluble solids content | °Bx | 5.0 | 10.0 | 15.0 | 20.0 | 25.0 |

| Inoculum ratio | — | 1:0 | 1:1 | 1:2 | 2:1 | 0:1 |

| Inoculum size | Log CFU/mL | 3 | 6 | 9 | 12 | 15 |

| Fermentation time | h | 48 | 72 | 96 | 108 | 120 |

| Symbols | Factors | Unit | Coded Levels | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Initial pH | — | 5.0 | 7.0 |

| B | Fermentation temperature | °C | 37 | 47 |

| C | Soluble solids content | °Bx | 10.0 | 25.0 |

| D | Inoculum ratio | — | 1:0 | 1:1 |

| E | Inoculum size | Log CFU/mL | 6 | 15 |

| F | Fermentation time | h | 96 | 120 |

| Run | A | B | C | D | E | F | GABA Content (g/L) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | 1 | −1 | 1.18 ± 0.02 |

| 2 | −1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1.2 ± 0.05 |

| 3 | −1 | 1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | −1 | 1.07 ± 0.10 |

| 4 | 1 | −1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | −1 | 1.14 ± 0.06 |

| 5 | 1 | 1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | 1 | 1.06 ± 0.04 |

| 6 | −1 | −1 | −1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1.29 ± 0.06 |

| 7 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | 1.32 ± 0.10 |

| 8 | −1 | −1 | 1 | −1 | −1 | 1 | 1.06 ± 0.01 |

| 9 | 1 | 1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | 1 | 0.92 ± 0.07 |

| 10 | −1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | −1 | −1 | 1.13 ± 0.08 |

| 11 | 1 | −1 | 1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | 1.03 ± 0.10 |

| 12 | 1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | −1 | −1 | 1.04 ± 0.14 |

| Symbols | Factors | Unit | Coded Levels | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −1 | 0 | 1 | |||

| A | Initial pH | — | 4.0 | 5.0 | 6.0 |

| B | Fermentation temperature | °C | 32 | 37 | 42 |

| C | Soluble solids content | °Bx | 5.0 | 10.0 | 15.0 |

| Run | Initial pH | Fermentation Temperature (°C) | Soluble Solids Content (°Bx) | GABA Content (g/L) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | −1 | −1 | 0 | 0.67 ± 0.04 |

| 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.78 ± 0.12 |

| 3 | −1 | 1 | 0 | 0.72 ± 0.08 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.80 ± 0.08 |

| 5 | 1 | 0 | −1 | 0.73 ± 0.03 |

| 6 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0.74 ± 0.05 |

| 7 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0.73 ± 0.10 |

| 8 | 0 | 1 | −1 | 0.75 ± 0.04 |

| 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.77 ± 0.05 |

| 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.76 ± 0.07 |

| 11 | −1 | 0 | 1 | 0.70 ± 0.11 |

| 12 | 0 | −1 | −1 | 0.70 ± 0.13 |

| 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.78 ± 0.07 |

| 14 | 0 | −1 | 1 | 0.73 ± 0.09 |

| 15 | −1 | 0 | −1 | 0.70 ± 0.06 |

| 16 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.77 ± 0.10 |

| 17 | 1 | −1 | 0 | 0.75 ± 0.07 |

Appendix B

References

- Varinthra, P.; Anwar, S.; Shih, S.C.; Liu, I.Y. The role of the GABAergic system on insomnia. Tzu Chi Med. J. 2024, 36, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.J.; Chen, Y.; Sun, T. From the gut to the brain, mechanisms and clinical applications of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) on the treatment of anxiety and insomnia. Front. Neurosci. 2025, 19, 1570173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inoue, K.; Shirai, T.; Ochiai, H.; Kasao, M.; Hayakawa, K.; Kimura, M.; Sansawa, H. Blood-pressure-lowering effect of a novel fermented milk containing γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) in mild hypertensives. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2003, 57, 490–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dastgerdi, A.H.; Sharifi, M.; Soltani, N. GABA administration improves liver function and insulin resistance in offspring of type 2 diabetic rats. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 23155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, J.R.; Zhao, X.L.; Zhao, X.; Wang, Q.; Li, P.; Gu, Q. Microbial-Derived γ-Aminobutyric Acid: Synthesis, Purification, Physiological Function, and Applications. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71, 14931–14946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pannerchelvan, S.; Rios-Solis, L.; Wong, F.W.F.; Zaidan, U.H.; Wasoh, H.; Mohamed, M.S.; Tan, J.S.; Mohamad, R.; Halim, M. Strategies for improvement of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) biosynthesis via lactic acid bacteria (LAB) fermentation. Food Funct. 2023, 14, 3929–3948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancini, A.; Carafa, I.; Franciosi, E.; Nardin, T.; Bottari, B.; Larcher, R.; Tuohy, K.M. In vitro probiotic characterization of high GABA producing strain Lactobacilluas brevis DSM 32386 isolated from traditional “wild” Alpine cheese. Ann. Microbiol. 2019, 69, 1435–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, Y.; Man, C.X.; Han, X.; Li, L.; Guo, Y.; Deng, Y.; Li, T.; Zhang, L.W.; Jiang, Y.J. Evaluation of improved γ-aminobutyric acid production in yogurt using Lactobacillus plantarum NDC75017. J. Dairy Sci. 2015, 98, 2138–2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q. Submerged fermentation of Lactobacillus rhamnosus YS9 for γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) production. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2013, 44, 183–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komatsuzaki, N.; Shima, J.; Kawamoto, S.; Momose, H.; Kimura, T. Production of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) by Lactobacillus paracasei isolated from traditional fermented foods. Food Microbiol. 2005, 22, 497–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thuy, D.T.B.; An, N.T.; Jayasena, V.; Vandamme, P. A comprehensive investigation into the production of gamma-aminobutyric acid by Limosilactobacillus fermentum NG16, a tuna gut isolate. Acta Aliment. 2022, 51, 302–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, E.A.; Calder, P.C. Effects of Citrus Fruit Juices and Their Bioactive Components on Inflammation and Immunity: A Narrative Review. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 712608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Zou, S.B.; Yan, X.; Yue, Y.; Zhang, S.F.; Ji, C.F.; Chen, Y.X.; Dai, Y.W.; Lin, X.P. Lactiplantibacillus plantarum A72 inoculation enhances Citrus juice quality: A systematic analysis of the strain’s fermentation properties, antioxidant capacities, and transcriptome pathways. Food Biosci. 2025, 64, 105878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, Q.; Liu, W.; Guo, J.J.; Ye, M.L.; Zhang, J.H. Effect of Six Lactic Acid Bacteria Strains on Physicochemical Characteristics, Antioxidant Activities and Sensory Properties of Fermented Orange Juices. Foods 2022, 11, 1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.L.; Lai, C.L.; Liang, Y.; Xiong, Q.; Chen, C.Y.; Ju, Z.R.; Jiang, Y.M.; Zhang, J. Improving the functional components and biological activities of navel orange juice through fermentation with an autochthonous strain Lactiplantibacillus paraplantarum M23. Food Bioprod. Process. 2025, 149, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.W.; Wang, Y.; Lan, H.B.; Wang, K.; Zhao, L.; Hu, Z.Y. Enhanced production of γ-aminobutyric acid in litchi juice fermented by Lactobacillus plantarum HU-C2W. Food Biosci. 2021, 42, 101155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Lu, X.L.; Yang, S.T.; Zou, Y.; Zeng, F.K.; Xiong, S.H.; Cao, Y.P.; Zhou, W. The anti-inflammatory activity of GABA-enriched Moringa oleifera leaves produced by fermentation with Lactobacillus plantarum LK-1. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1093036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanklai, J.; Somwong, T.C.; Rungsirivanich, P.; Thongwai, N. Screening of GABA-Producing Lactic Acid Bacteria from Thai Fermented Foods and Probiotic Potential of Levilactobacillus brevis F064A for GABA-Fermented Mulberry Juice Production. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.W.; Wu, J.Y.; Hu, D.; Li, J.; Zhu, W.W.; Yuan, L.X.; Chen, X.S.; Yao, J.M. Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid-Producing Levilactobacillus brevis Strains as Probiotics in Litchi Juice Fermentation. Foods 2023, 12, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Li, J.; Mao, K.M.; Gao, J.; Li, X.Y.; Zhi, T.X.; Sang, Y.X. Anti-hangover and anti-hypertensive effects in vitro of fermented persimmon juice. CYTA-J. Food 2019, 17, 960–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.J.; Wang, Y.; Nan, B.; Cao, Y.; Piao, C.H.; Li, X.; Wang, Y.H. Optimization of fermentation for gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) production by Lactiplantibacillus plantarum Lp3 and the development of fermented soymilk. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 195, 115841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.C.; Zhang, M.; Li, T.; Zhang, X.X.; Wang, L. Enhance Production of γ-Aminobutyric Acid (GABA) and Improve the Function of Fermented Quinoa by Cold Stress. Foods 2022, 11, 3908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meena, K.K.; Taneja, N.K.; Jain, D.; Ojha, A.; Kumawat, D.; Mishra, V. In Vitro Assessment of Probiotic and Technological Properties of Lactic Acid Bacteria Isolated from Indigenously Fermented Cereal-Based Food Products. Fermentation 2022, 8, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Adams, M.C. In vitro assessment of the upper gastrointestinal tolerance of potential probiotic dairy propionibacteria. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2004, 91, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghashghaei, T.; Soudi, M.R.; Hoseinkhani, S. Optimization of Xanthan Gum Production from Grape Juice Concentrate Using Plackett-Burman Design and Response Surface Methodology. Appl. Food Biotechnol. 2016, 3, 15–23. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, D.; Sharma, N. Optimization of fermentation of himalayan black tea beverage using response surface methodology. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2025, 229, 118107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, P.H.; Verscheure, L.; Le, T.T.; Verheust, Y.; Raes, K. Implementation of HPLC Analysis for γ-Aminobutyric Acid (GABA) in Fermented Food Matrices. Food Anal. Methods 2020, 13, 1190–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, A.F. The continuing importance of bile acids in liver and intestinal disease. Arch. Intern. Med. 1999, 159, 2647–2658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, Y.H.; Miao, K.; Niyaphorn, S.; Qu, X.J. Production of Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid from Lactic Acid Bacteria: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rayavarapu, B.; Tallapragada, P.; Usha, M.S. Optimization and comparison of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) production by LAB in soymilk using RSM and ANN models. Beni-Suef Univ. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2021, 10, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.; Perrier, J.M.; Gervais, P. Effect of the osmotic conditions during sporulation on the subsequent resistance of bacterial spores. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2008, 80, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kook, M.C.; Cho, S.C. Production of GABA (gamma amino butyric acid) by Lactic Acid Bacteria. Korean J. Food Sci. Anim. Resour. 2013, 33, 377–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Maimaitiyiming, R.; Hong, J.Y.; Wang, L.; Mu, Y.; Liu, B.Z.; Zhang, H.M.; Chen, K.P.; Aihaiti, A. Optimization of tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) juice fermentation process and analysis of its metabolites during fermentation. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1344117, Corrigendum in Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1423909. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2024.1423909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Source | Sum of Squares | Df | Mean Square | F-Value | p-Value | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 0.1310 | 6 | 0.0218 | 8.86 | 0.0150 | Significant |

| A-Initial pH | 0.0413 | 1 | 0.0413 | 16.74 | 0.0094 | ** |

| B-Fermentation temperature | 0.0290 | 1 | 0.0290 | 11.76 | 0.0186 | * |

| C-Soluble solids content | 0.0459 | 1 | 0.0459 | 18.62 | 0.0076 | * |

| D-Starter ratio | 0.0039 | 1 | 0.0039 | 1.60 | 0.2623 | |

| E-Inoculum size | 0.0023 | 1 | 0.0023 | 0.91 | 0.3830 | |

| F-Fermentation time | 0.0087 | 1 | 0.0087 | 3.54 | 0.1188 | |

| Residual | 0.0123 | 5 | 0.0025 | |||

| Cor Total | 0.1433 | 11 | ||||

| R2 | 0.9140 | |||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.8109 | |||||

| Predicted R2 | 0.5049 | |||||

| C.V.% | 4.41 |

| Source | Sum of Squares | Df | Mean Square | F-Value | p-Value | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 0.0187 | 9 | 0.0021 | 9.85 | 0.0032 | Significant |

| A-Initial pH | 0.0046 | 1 | 0.0046 | 21.88 | 0.0023 | ** |

| B-Fermentation temperature | 0.0009 | 1 | 0.0009 | 4.48 | 0.0721 | |

| C-Soluble solids content | 0.0006 | 1 | 0.0006 | 2.72 | 0.1433 | |

| AB | 0.0015 | 1 | 0.0015 | 7.33 | 0.0303 | * |

| AC | 0.0007 | 1 | 0.0007 | 3.09 | 0.1220 | |

| BC | 0.0003 | 1 | 0.0003 | 1.28 | 0.2959 | |

| A2 | 0.0044 | 1 | 0.0044 | 20.82 | 0.0026 | ** |

| B2 | 0.0032 | 1 | 0.0032 | 15.23 | 0.0059 | ** |

| C2 | 0.0015 | 1 | 0.0015 | 7.07 | 0.0325 | * |

| Residual | 0.0015 | 7 | 0.0002 | |||

| Lack of fit | 0.0002 | 3 | 0.0001 | 0.17 | 0.9108 | Not significant |

| Pure error | 0.0013 | 4 | 0.0003 | |||

| Cor toal | 0.0202 | 16 | ||||

| R2 | 0.9268 | |||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.8327 | |||||

| Predicted R2 | 0.7656 | |||||

| C.V.% | 1.96 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yin, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, R.; Zhao, N.; Liu, H.; Tang, Y.; Qin, N.; Dai, Y.; Lin, X. Screening of Lactic Acid Bacteria and RSM-Based Optimization for Enhancing γ-Aminobutyric Acid (GABA) Accumulation in Orange Juice. Foods 2026, 15, 71. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010071

Yin S, Wang Y, Zhao R, Zhao N, Liu H, Tang Y, Qin N, Dai Y, Lin X. Screening of Lactic Acid Bacteria and RSM-Based Optimization for Enhancing γ-Aminobutyric Acid (GABA) Accumulation in Orange Juice. Foods. 2026; 15(1):71. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010071

Chicago/Turabian StyleYin, Shufeng, Yiyao Wang, RuiXue Zhao, Ning Zhao, Hao Liu, Yining Tang, Ningbo Qin, Yiwei Dai, and Xinping Lin. 2026. "Screening of Lactic Acid Bacteria and RSM-Based Optimization for Enhancing γ-Aminobutyric Acid (GABA) Accumulation in Orange Juice" Foods 15, no. 1: 71. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010071

APA StyleYin, S., Wang, Y., Zhao, R., Zhao, N., Liu, H., Tang, Y., Qin, N., Dai, Y., & Lin, X. (2026). Screening of Lactic Acid Bacteria and RSM-Based Optimization for Enhancing γ-Aminobutyric Acid (GABA) Accumulation in Orange Juice. Foods, 15(1), 71. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010071