No- and Low-Alcohol Wines: Perception and Acceptance in a Traditional Wine Region in Northern Italy

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Scope

1.2. Hypotheses Development

2. Methodology

2.1. Survey Design

2.2. Ethical Approval and Consent

2.3. Sample and Data Collection

2.4. Data Processing and Analysis

3. Result and Discussion

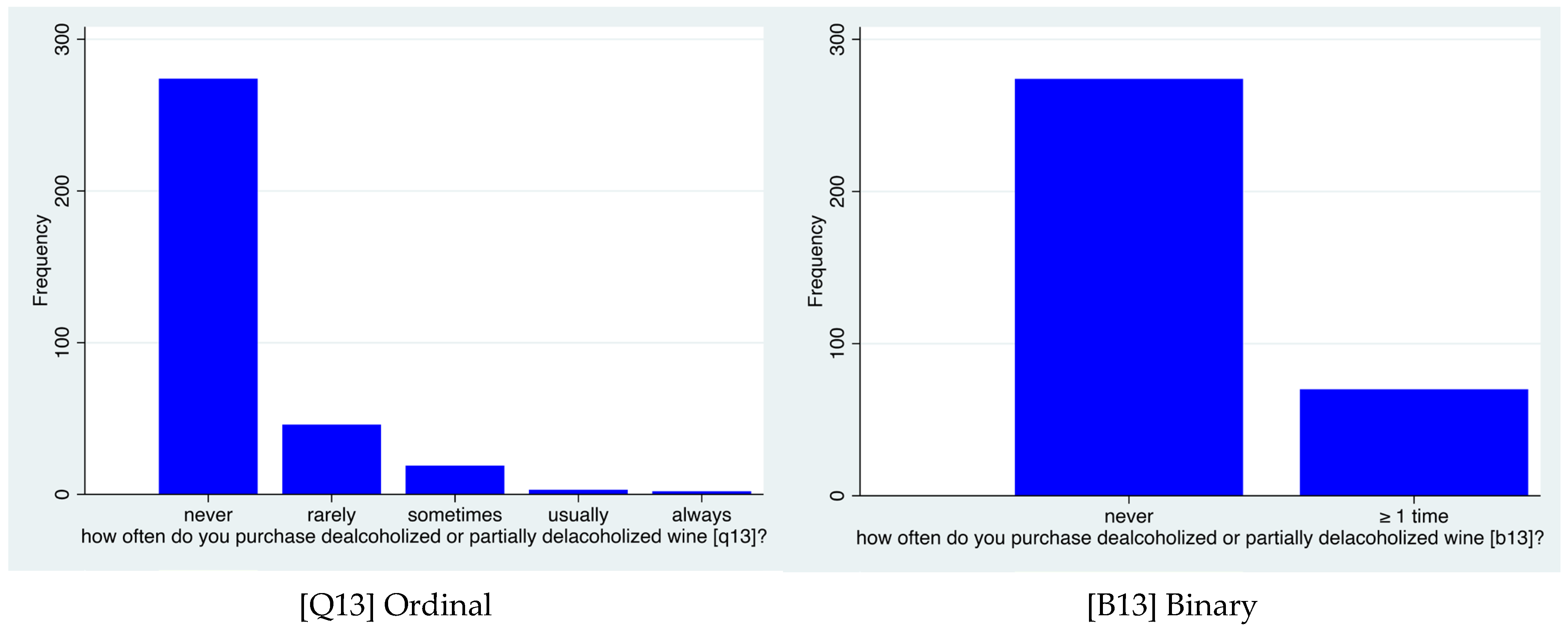

3.1. Descriptive Findings

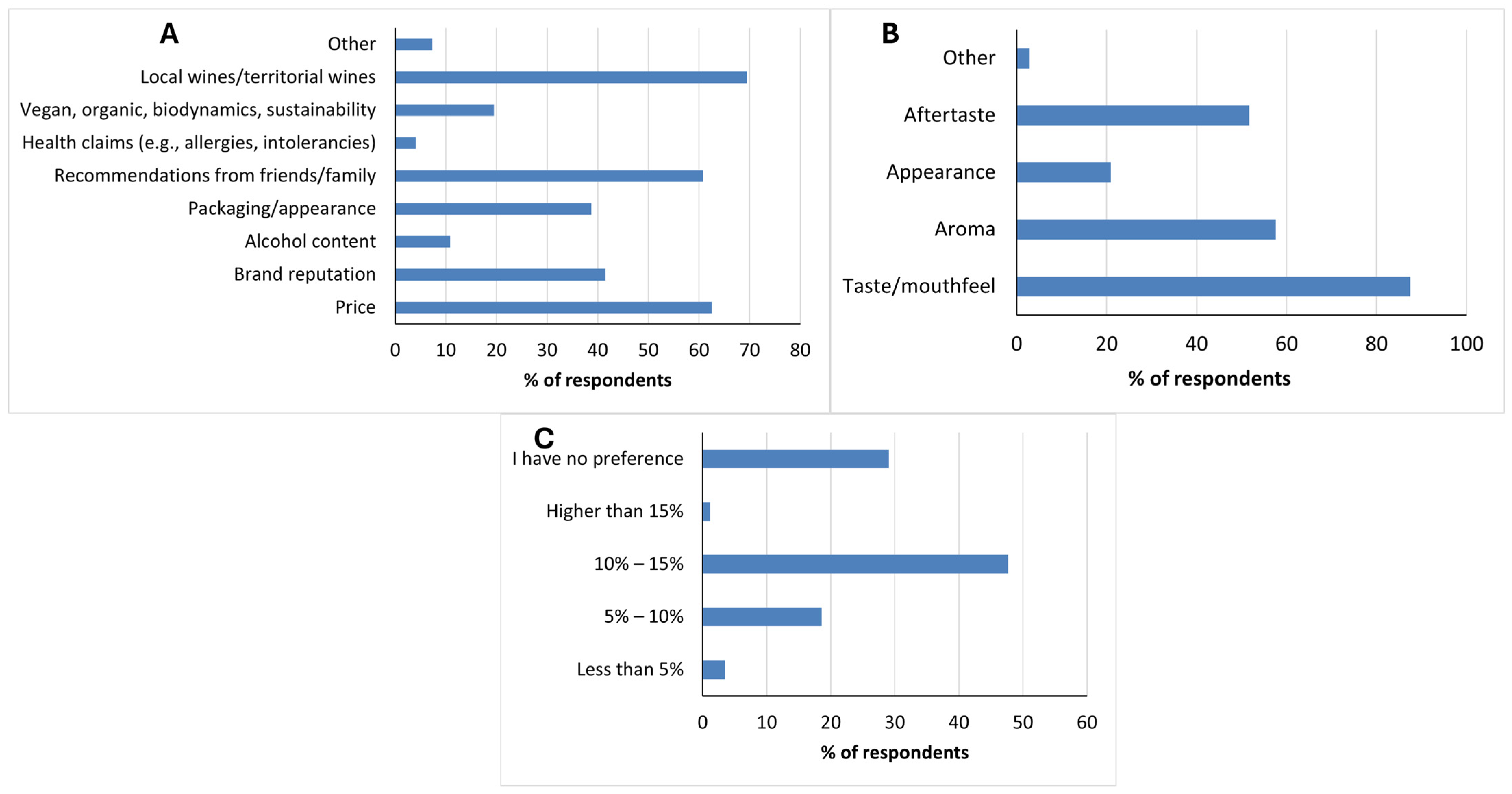

3.1.1. General Wine Consumption Behavior

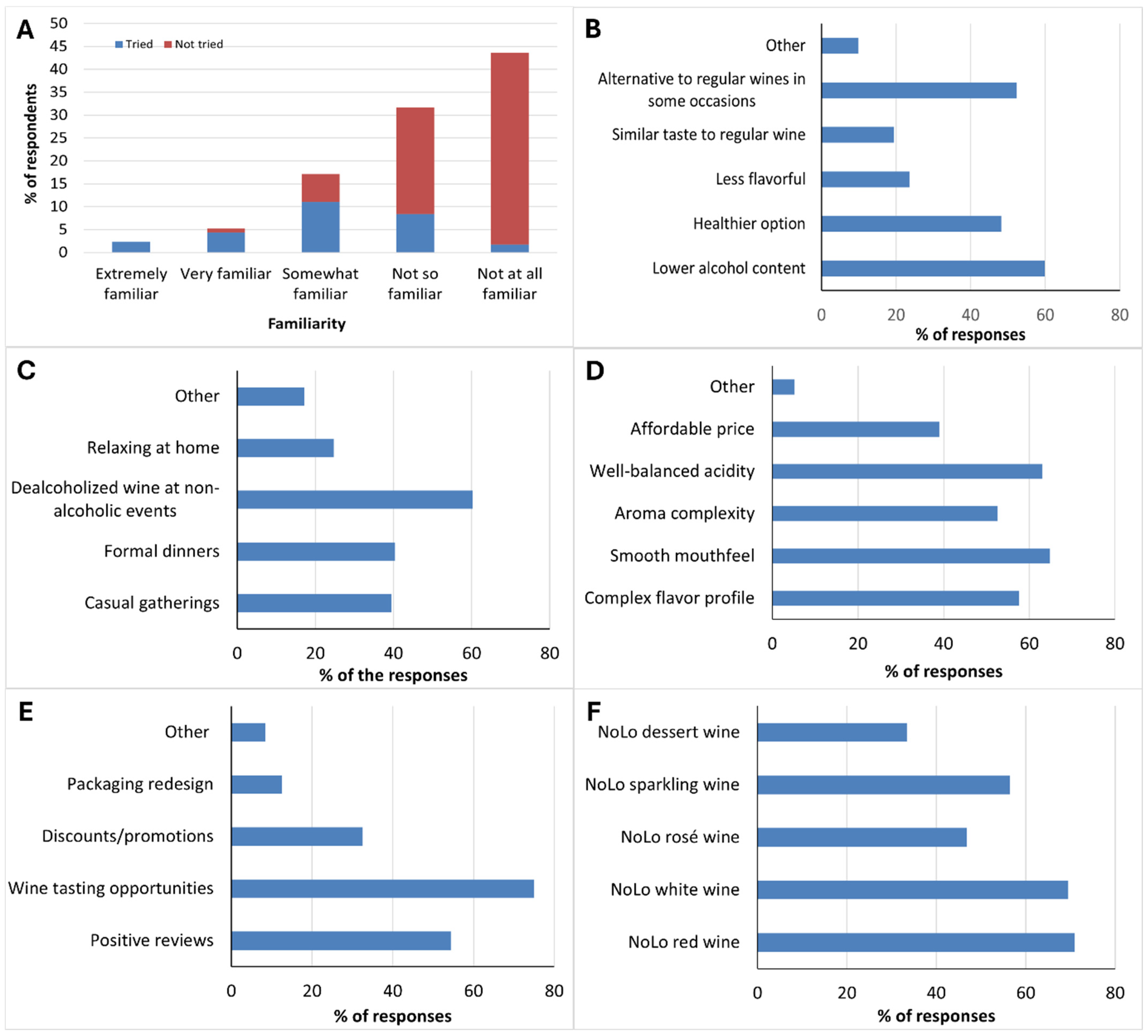

3.1.2. Consumer Awareness and Perceptions Toward NoLo Wines

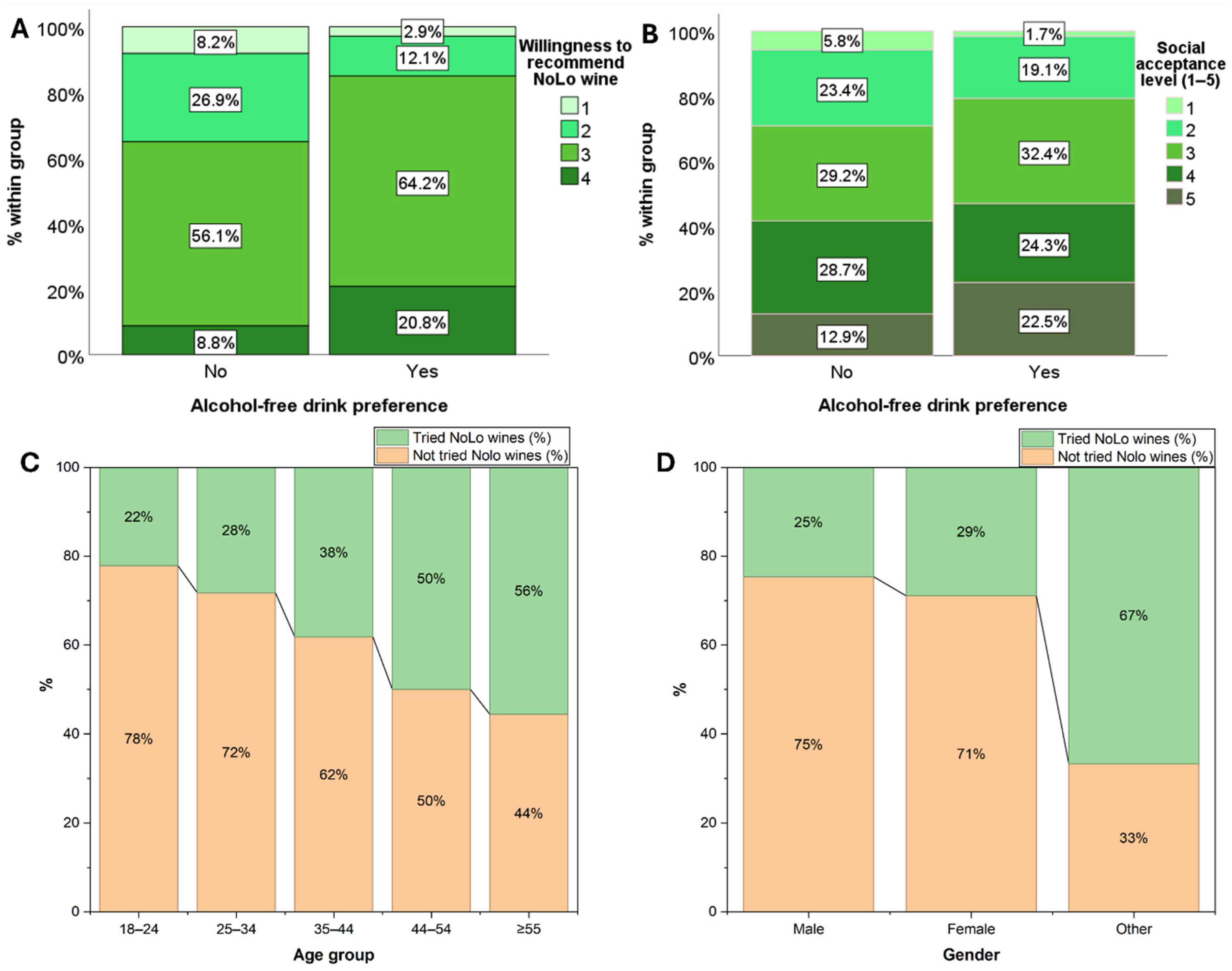

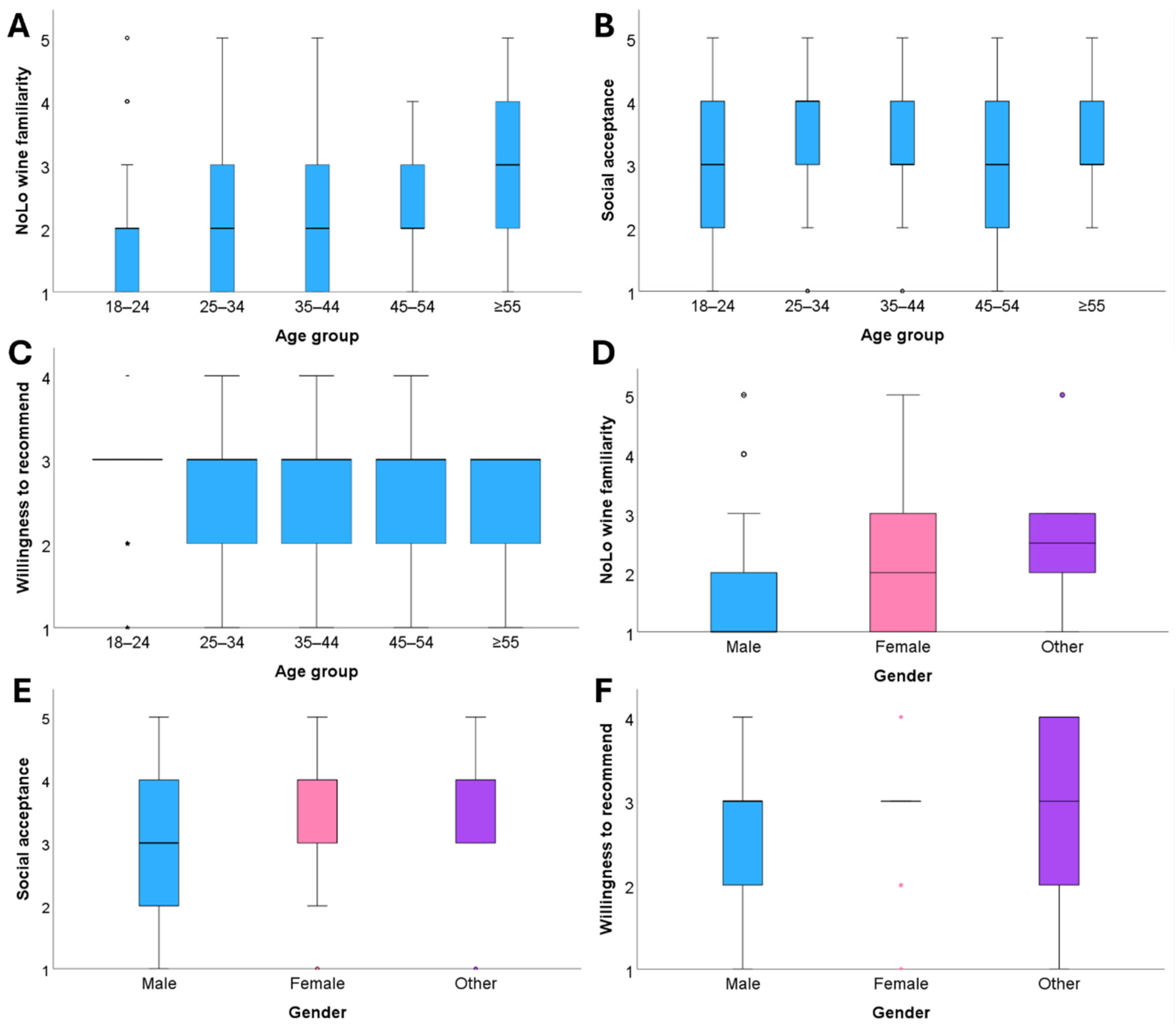

3.2. Hypothesis Testing

3.3. Logit and Probit Models

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nicholls, E. “I don’t want to introduce it into new places in my life”: The marketing and consumption of no and low alcohol drinks. Int. J. Drug Policy 2023, 119, 104149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IWSR. Consumers Show Preference for Downtrading in Beverage Alcohol, but Sentiment Is Improving in Some Markets. 2024. Available online: https://www.theiwsr.com/insight/consumers-show-preference-for-downtrading-in-beverage-alcohol-but-sentiment-is-improving-in-some-markets/ (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- European Parliament; CEU. Regulation (EU) 2021/2117 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 2 December 2021 amending Regulations (EU) No 1308/2013 establishing a common organisation of the markets in agricultural products, (EU) No 1151/2012 on quality schemes for agricultural products and foodstuffs, (EU) No 251/2014 on the definition, description, presentation, labelling and the protection of geographical indications of aromatised wine products and (EU) No 228/2013 laying down specific measures for agriculture in the outermost regions of the Union. Off. J. Eur. Union 2021, 435, 262–314. [Google Scholar]

- Akhtar, W.; Ceci, A.T.; Longo, E.; Marconi, M.A.; Lonardi, F.; Boselli, E. Dealcoholized wine: Techniques, sensory impacts, stability, and perspectives of a growing industry. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2025, 24, e70171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiarini, M.; Calabrese, F.M.; Canfora, I.; De Boni, A.; Tricarico, G.; De Angelis, M. Exploring the Multifaced Potential of Dealcoholized Wine: A Focus on Techniques, Legislation Compliances, and Microbiological Aspects. Food Rev. Int. 2025, 12, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liguori, L.; Albanese, D.; Crescitelli, A.; Di Matteo, M.; Russo, P. Impact of dealcoholization on quality properties in white wine at various alcohol content levels. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 56, 3707–3720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, J.; Zhang, Z.; Jin, A.; Tan, M.; Jiang, S.; Li, Y. A Critical Review of Alcohol Reduction Methods for Red Wines from the Perspective of Phenolic Compositions. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 13, e70401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, Y.; Ricci, A.; Parpinello, G.P.; Versari, A. Dealcoholized wine: A scoping review of volatile and non-volatile profiles, consumer perception, and health benefits. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2024, 17, 3525–3545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sam, F.E.; Ma, T.-Z.; Salifu, R.; Wang, J.; Jiang, Y.-M.; Zhang, B.; Han, S.-Y. Techniques for dealcoholization of wines: Their impact on wine phenolic composition, volatile composition, and sensory characteristics. Foods 2021, 10, 2498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, M.; Estévez, S.; Kontoudakis, N.; Fort, F.; Canals, J.; Zamora, F. Influence of partial dealcoholization by reverse osmosis on red wine composition and sensory characteristics. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2013, 237, 481–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corona, O.; Liguori, L.; Albanese, D.; Di Matteo, M.; Cinquanta, L.; Russo, P. Quality and volatile compounds in red wine at different degrees of dealcoholization by membrane process. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2019, 245, 2601–2611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumbili, E.W.; Leonard, P.; Larkin, J.; Houghton, F. Prioritising research on marketing and consumption of No and Low (NoLo) alcoholic beverages in Ireland. Int. J. Drug Policy 2025, 139, 104794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saliba, A.J.; Ovington, L.A.; Moran, C.C. Consumer demand for low-alcohol wine in an Australian sample. Int. J. Wine Res. 2013, 5, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, I.; Deroover, K.; Kavanagh, M.; Beckett, E.; Akanbi, T.; Pirinen, M.; Bucher, T. Australian consumer perception of non-alcoholic beer, white wine, red wine, and spirits. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2024, 35, 100886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rui, M.; Rosa, F.; Viberti, A.; Brun, F.; Blanc, S.; Massaglia, S. Anticipating consumer preference for low-alcohol wine: A machine learning analysis based on consumption habits and socio-demographics. In Proceedings of the 45th OIV Congress, Dijon, France, 14–18 October 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ford, H.; Dolan, R.; Goodman, S.; Bastian, S.; Pearson, W.; Corsi, A.M. Exploring consumers’ drinking behaviour regarding no-, low-and mid-alcohol wines: A systematic scoping review and guiding framework. J. Mark. Manag. 2025, 41, 703–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes-Fernández, R.; del Campo-Villares, J.L. Exploring the market for dealcoholized wine in Spain: Health trends, demographics, and the role of emerging consumer preferences. Beverages 2025, 11, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essedielle. The New Era of NoLo Wines in Italy: Understanding its Customers. Available online: https://www.essedielleenologia.com/en/news/nolo-wines-law-italy/ (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Stasi, A.; Bimbo, F.; Viscecchia, R.; Seccia, A. Italian consumers׳ preferences regarding dealcoholized wine, information and price. Wine Econ. Policy 2014, 3, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICQRF—Cantina Italia: Report n. 8/2025; Dati al 31 Luglio 2025 dei Vini, Mosti, Denominazioni Detenuti in Italia. 2025. Available online: https://www.masaf.gov.it/flex/cm/pages/ServeBLOB.php/L/IT/IDPagina/7817 (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Shaw, C.L.; Dolan, R.; Corsi, A.M.; Goodman, S.; Pearson, W. Exploring the barriers and triggers towards the adoption of low- and no-alcohol (NOLO) wines. Food Qual. Prefer. 2023, 110, 104932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleijnen, M.; Lee, N.; Wetzels, M. An exploration of consumer resistance to innovation and its antecedents. J. Econ. Psychol. 2009, 30, 344–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaichkowsky, J.L. Measuring the involvement construct. J. Consum. Res. 1985, 12, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurent, G.; Kapferer, J.-N. Measuring Consumer Involvement Profiles. J. Mark. Res. 1985, 22, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IWSR. Millennials Drive No-Alcohol Gains in the US. 2024. Available online: https://www.theiwsr.com/insight/millennials-drive-no-alcohol-gains-in-the-us/ (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Rogers, E. Diffusion of Innovations 5th; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, R.L. A cognitive model of the antecedents and consequences of satisfaction decisions. J. Mark. Res. 1980, 17, 460–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pliner, P.; Hobden, K. Development of a scale to measure the trait of food neophobia in humans. Appetite 1992, 19, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corsi, A.; Mazzarino, S.; Pomarici, E. The Italian wine industry. In The Palgrave Handbook of Wine Industry Economics; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 47–76. [Google Scholar]

- Bowdring, M.A.; McCarthy, D.M.; Fairbairn, C.E.; Prochaska, J.J. Non-alcoholic beverage consumption among US adults who consume alcohol. Addiction 2024, 119, 1080–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, K.; Galati, A.; Chatterjee, S.; Chaudhuri, R.; Vrontis, D.; Migliore, G. Uncorking the psychological factors behind habits and NoLo wine preferences. Br. Food J. 2025, 127, 1420–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, N.; Blackwell, A.K.M.; Ferrar, J.; De-Loyde, K.; Pilling, M.A.; Munafò, M.R.; Marteau, T.M.; Hollands, G.J. Impact on alcohol selection and online purchasing of changing the proportion of available non-alcoholic versus alcoholic drinks: A randomised controlled trial. PLoS Med. 2023, 20, e1004193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baiano, A. The Willingness to Pay for Non-Alcoholic Beer: A Survey on the Sociodemographic Factors and Consumption Behavior of Italian Consumers. Foods 2025, 14, 2399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masson, J.; Aurier, P.; d’Hauteville, F. Effects of non-sensory cues on perceived quality: The case of low-alcohol wine. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2008, 20, 215–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruwer, J.; Jiranek, V.; Halstead, L.; Saliba, A. Lower alcohol wines in the UK market: Some baseline consumer behaviour metrics. Br. Food J. 2014, 116, 1143–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucher, T.; Deroover, K.; Stockley, C. Low-Alcohol Wine: A Narrative Review on Consumer Perception and Behaviour. Beverages 2018, 4, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrysochou, P. Drink to get drunk or stay healthy? Exploring consumers’ perceptions, motives and preferences for light beer. Food Qual. Prefer. 2014, 31, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooi, E.; Sarstedt, M.; Mooi-Reci, I. Market Research; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp, L. Stata Meta-Analysis Reference Manual; Stata: Release 17, Statistical software; StataCorp LLC: College Station, TX, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, D.E.; Mitry, D.J. Cultural Convergence: Consumer Behavioral Changes in the European Wine Market. J. Wine Res. 2007, 18, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohana-Levi, N.; Netzer, Y. Long-Term Trends of Global Wine Market. Agriculture 2023, 13, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IWSR. No-Alcohol Share of Overall Alcohol Market Expected to Grow to Nearly 4% by 2027. 2023. Available online: https://www.theiwsr.com/insight/no-alcohol-share-of-overall-alcohol-market-expected-to-grow-to-nearly-4-by-2027/ (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Del Rey, R.; Loose, S. State of the International Wine Market in 2022: New market trends for wines require new strategies. Wine Econ. Policy 2023, 12, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cei, L.; Rossetto, L. The demand for sparkling wine: Insights on a diversified European market. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2024, 36, 505–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanco, M.; Lerro, M.; Marotta, G. Consumers’ Preferences for Wine Attributes: A Best-Worst Scaling Analysis. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmieri, N.; Perito, M.A. Consumers’ Willingness to Consume Sustainable and Local Wine in Italy. Y. Ital. J. Food Sci. 2020, 32, 222–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gow, J.; Moscovici, D.; Rana, R.; Rinaldi, A.; Ugaglia, A.A.; Valenzuela, L.; Mihailescu, R.; Haque, R. Determinants of Purchasing Sustainably Produced Wines by Italian Wine Consumers. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanigro, M.; Appleby, C.; Menke, S.D. The wine headache: Consumer perceptions of sulfites and willingness to pay for non-sulfited wines. Food Qual. Prefer. 2014, 31, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corduas, M.; Cinquanta, L.; Ievoli, C. The importance of wine attributes for purchase decisions: A study of Italian consumers’ perception. Food Qual. Prefer. 2013, 28, 407–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C.D.; Kuang, Y.; Jankuhn, N. You’re Not A Teetotaler, are You? A Framework of Nonalcoholic Wine Consumption Motives and Outcomes. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2020, 26, 372–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waehning, N.; Wells, V.K. Product, individual and environmental factors impacting the consumption of no and low alcoholic drinks: A systematic review and future research agenda. Food Qual. Prefer. 2024, 117, 105163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucher, T.; Frey, E.; Wilczynska, M.; Deroover, K.; Dohle, S. Consumer perception and behaviour related to low-alcohol wine: Do people overcompensate? Public Health Nutr. 2020, 23, 1939–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockshin, L.; Corsi, A.M. Consumer behaviour for wine 2.0: A review since 2003 and future directions. Wine Econ. Policy 2012, 1, 2–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blog. Italians’ Incomes are Growing, but Inflation is Burning Them. Portofino is the New “Capital” of Wealth, in the Cities Wide Scissors. 2024. Available online: https://excelleraint.com/i-redditi-degli-italiani-crescono-ma-l-inflazione-li-brucia-portofino-nuova-capitale-della-ricchezza/ (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Mosikyan, S.; Dolan, R.; Corsi, A.M.; Bastian, S. A systematic literature review and future research agenda to study consumer acceptance of novel foods and beverages. Appetite 2024, 203, 107655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günden, C.; Atakan, P.; Yercan, M.; Mattas, K.; Knez, M. Consumer Response to Novel Foods: A Review of Behavioral Barriers and Drivers. Foods 2024, 13, 2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickering, G.J.; Kemp, B. Understanding Sparkling Wine Consumers and Purchase Cues: A Wine Involvement Perspective. Beverages 2024, 10, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meillon, S.; Urbano, C.; Guillot, G.; Schlich, P. Acceptability of partially dealcoholized wines—Measuring the impact of sensory and information cues on overall liking in real-life settings. Food Qual. Prefer. 2010, 21, 763–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamorte, S.A.; Agnoli, L. Analysing consumers’ decision-making process for non-alcoholic spirit drinks and dealcoholized aromatized wines. In Proceedings of the IVES Conference Series, Dijon, France, 14–18 October 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, K. The emergence of lower-alcohol beverages: The case of beer. J. Wine Econ. 2023, 18, 66–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perman-Howe, P.R.; Holmes, J.; Brown, J.; Kersbergen, I. Characteristics of consumers of alcohol-free and low-alcohol drinks in Great Britain: A cross-sectional study. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2024, 43, 1686–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Times, T. Italy Lifts Ban on Naming of Alcohol-Free Wines. 2025. Available online: https://www.thetimes.com/world/europe/article/non-alcoholic-wine-sold-italy-minister-g0tn27jbm (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Cravero, M.C.; Laureati, M.; Spinelli, S.; Bonello, F.; Monteleone, E.; Proserpio, C.; Lottero, M.R.; Pagliarini, E.; Dinnella, C. Profiling Individual Differences in Alcoholic Beverage Preference and Consumption: New Insights from a Large-Scale Study. Foods 2020, 9, 1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moffatt, P. Experimetrics: Econometrics for Experimental Economics; Bloomsbury Publishing: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

| Characteristic | Category | % of Respondents |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 39 |

| Female | 59.3 | |

| Non-binary/Other | 0.3 | |

| Prefer not to disclose | 1.5 | |

| Age | 18–24 | 50 |

| 25–34 | 32.9 | |

| 35–44 | 9.9 | |

| 45–54 | 4.7 | |

| 55–64 | 2.3 | |

| 65+ | 0.3 | |

| Occupation | Student | 67.7 |

| Teacher | 4.9 | |

| Business owner | 0.9 | |

| Employee | 18.9 | |

| Retired | 0 | |

| Other | 7.6 | |

| Income | No income | 29.7 |

| Under €15,000 | 32 | |

| Between €15,000 and €29,999 | 21.8 | |

| Between €30,000 and €49,999 | 10.2 | |

| Between €50,000 and €74,999 | 4.4 | |

| Between €75,000 and €99,999 | 0.9 | |

| Over €100,000 | 1.2 |

| Variable | Category | % of Respondents |

|---|---|---|

| Frequency of wine consumption | Daily | 3.5 |

| Weekly | 29.1 | |

| Monthly | 24.1 | |

| Rarely | 28.5 | |

| Never | 14.8 | |

| General alcohol-free drink behavior | Yes | 50.3 |

| No | 49.7 | |

| Preferred wine type | Red wine | 57.3 |

| White wine | 55.5 | |

| Rosé wine | 17.7 | |

| Sparkling wine | 37.5 | |

| Dessert wine | 57 | |

| No preference | 8.4 | |

| Other | 1.7 | |

| Average spending per bottle | <€10 | 38.4 |

| €10–€20 | 45.6 | |

| €20–€30 | 12.2 | |

| €30–€40 | 2.6 | |

| More than €40 | 1.2 |

| Dependent Variable (DV) | N. Categories (K) | Kruskal–Wallis (H) | Ties |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social acceptance | 2 | 4.447 ** (1) | Yes |

| Willingness to recommend | 2 | 23.121 *** (1) | Yes |

| Dependent Variable (DV) | Independent Variable | Categories (k) | Chi-Squared χ2 (df) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tried NoLo wine | Age | 5 | 12.003 ** (4) |

| Tried Nolo Wine | Gender | 3 | 5.301 * (2) |

| Age | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable (DV) | Categories (k) | Kruskal–Wallis H (df) | Ties |

| NoLo wine familiarity | 5 | 10.850 ** (4) | Yes |

| NoLo wine purchase frequency | 5 | 3.448 (4) | Yes |

| Social acceptance | 5 | 3.873 (4) | Yes |

| Willingness to recommend | 5 | 5.797 (4) | Yes |

| Gender | |||

| Dependent Variable (DV) | Categories (k) | Kruskal–Wallis H (df) | Ties |

| NoLo wine familiarity | 3 | 8.343 ** (2) | Yes |

| NoLo wine purchase frequency | 3 | 2.789 (2) | Yes |

| Social acceptance | 3 | 12.794 *** (2) | Yes |

| Willingness to recommend | 3 | 17.803 *** (2) | Yes |

| Dependent Variable: [Q13] Frequency of NoLo Wine Purchase | ||

|---|---|---|

| Model | Logit | Probit |

| [Q1] Traditional wine drinking frequency | ||

| 1. rare (base level) | – | – |

| 2. from time to time | 0.486 (0.730) | 0.331 (0.390) |

| 3. monthly | 0.540 (0.738) | 0.367 (0.404) |

| 4. weekly | 0.444 (0.786) | 0.218 (0.432) |

| 5. daily | 0.407 (1.503) | 0.497 (0.709) |

| [Q2] Alcohol-free drink status | ||

| 1. no (base level) | – | – |

| 2. yes | 0.846 * (0.485) | 0.405 (0.251) |

| [Q4] Spending habit | ||

| 1. <€10 (base level) | – | – |

| 2. €10–€20 | 0.747 (0.532) | 0.464 (0.286) |

| 3. €20–€30 | 0.362 (0.726) | 0.298 (0.386) |

| 4. >€30 | 1.187 (1.098) | 0.547 (0.631) |

| [Q7] Preferred alcohol level in wine | ||

| 1. no preference (base level) | – | – |

| 2. <5% | 0.970 (1.130) | 0.466 (0.629) |

| 3. 5–10% | 1.319 ** (0.616) | 0.591 * (0.317) |

| 4. >10% | −1.272 ** (0.580) | −0.702 ** (0.312) |

| [Q8] NoLo wine familiarity | ||

| 1. not familiar (base level) | – | – |

| 2. not so familiar | 1.363 ** (0.674) | 0.651 * (0.333) |

| 3. somewhat familiar | 2.106 *** (0.733) | 1.130 *** (0.371) |

| 4. very familiar | 4.977 *** (1.231) | 2.655 *** (0.659) |

| 5. extremely familiar | 3.955 *** (1.534) | 2.109 *** (0.813) |

| [Q9] NoLo wine tasting experience | ||

| 1. no (base level) | – | – |

| 2. yes | 3.469 *** (0.576) | 1.891 *** (0.298) |

| [Q14] NoLo wine taste importance | ||

| 1. not important (base level) | – | – |

| 2. not so important | −0.484 (1.427) | −0.290 (0.791) |

| 3. somewhat important | −0.024 (1.219) | 0.030 (0.658) |

| 4. very important | 0.341 (1.152) | 0.257 (0.626) |

| 5. extremely important | −0.595 (1.217) | −0.237 (0.657) |

| Age | ||

| 1. ≤24 (base level) | – | – |

| 2. 25–34 | −1.224 * (0.664) | −0.615 * (0.355) |

| 3. 35–44 | −2.177 * (1.125) | −1.192 ** (0.607) |

| 4. 45–54 | −0.364 (1.081) | −0.180 (0.606) |

| 5. ≥55 | −2.228 (1.841) | −1.200 (1.034) |

| Gender | ||

| 1. male (base level) | – | – |

| 2. female | 0.032 (0.511) | –0.016 (0.272) |

| 3. other | −1.669 (1.362) | −0.977 (0.795) |

| Income | ||

| 1. no-income (base level) | – | – |

| 2. <€15,000 | 0.022 (0.592) | −0.079 (0.315) |

| 3. €15,000–€29,000 | 1.141 (0.767) | 0.544 (0.418) |

| 4. €30,000–€49,000 | 1.569 (1.018) | 0.742 (0.553) |

| 5. €50,000–€74,000 | −1.805 (1.231) | −1.152 (0.691) |

| 6. ≥€75,000 | 2.169 (2.144) | 0.912 (1.197) |

| Intercept | −5.334 *** (1.401) | −2.829 *** (9.725) |

| N. Observations | 344 | 344 |

| LR (31) | 185.63 *** | 183.69 *** |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.534 | 0.529 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Akhtar, W.; Duley, G.; Calvia, M.; Longo, E.; Sait, U.; Boselli, E. No- and Low-Alcohol Wines: Perception and Acceptance in a Traditional Wine Region in Northern Italy. Foods 2026, 15, 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010042

Akhtar W, Duley G, Calvia M, Longo E, Sait U, Boselli E. No- and Low-Alcohol Wines: Perception and Acceptance in a Traditional Wine Region in Northern Italy. Foods. 2026; 15(1):42. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010042

Chicago/Turabian StyleAkhtar, Wasim, Gavin Duley, Massimiliano Calvia, Edoardo Longo, Unais Sait, and Emanuele Boselli. 2026. "No- and Low-Alcohol Wines: Perception and Acceptance in a Traditional Wine Region in Northern Italy" Foods 15, no. 1: 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010042

APA StyleAkhtar, W., Duley, G., Calvia, M., Longo, E., Sait, U., & Boselli, E. (2026). No- and Low-Alcohol Wines: Perception and Acceptance in a Traditional Wine Region in Northern Italy. Foods, 15(1), 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010042