Collagen from Bovine Omentum: Extraction and Characterization

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemical Reagents

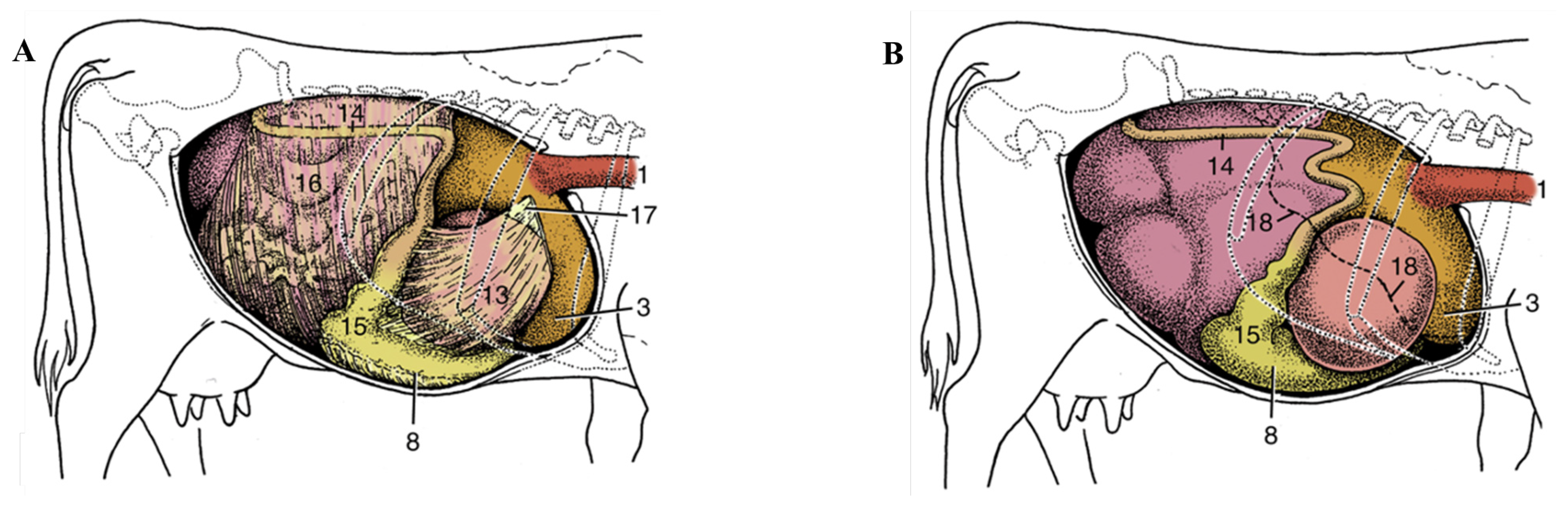

2.2. Bovine Omentum Preparation

2.3. Determination of Proximate Composition, Amino Acid Composition, and Fatty Acid Profile of Bovine Omentum

2.3.1. Proximate Analysis

2.3.2. Fatty Acid Analysis

2.3.3. Amino Acid (AA) Analysis

2.4. Extraction of Collagen from Bovine Omentum

2.5. Analyses of Extracted Collagen

2.5.1. Yield

2.5.2. Degree of Hydrolysis (DH), Free Amino Acid Content, and Protein Content

2.5.3. Hydroxyproline Content

2.5.4. Determination of Salt and pH Solubility of Collagen Samples

2.5.5. Emulsifying Properties

2.5.6. FTIR Analysis of Collagen Samples

2.5.7. Amino Acid Composition of Extracted Collagen Samples

2.5.8. Protein Patterns of Collagen Samples

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Proximate Composition, Fatty Acid Profile, and Amino Acid Profile of Bovine Omentum

3.2. Collagen Yield, Degree of Hydrolysis, Free Amino Acid, and Protein Content

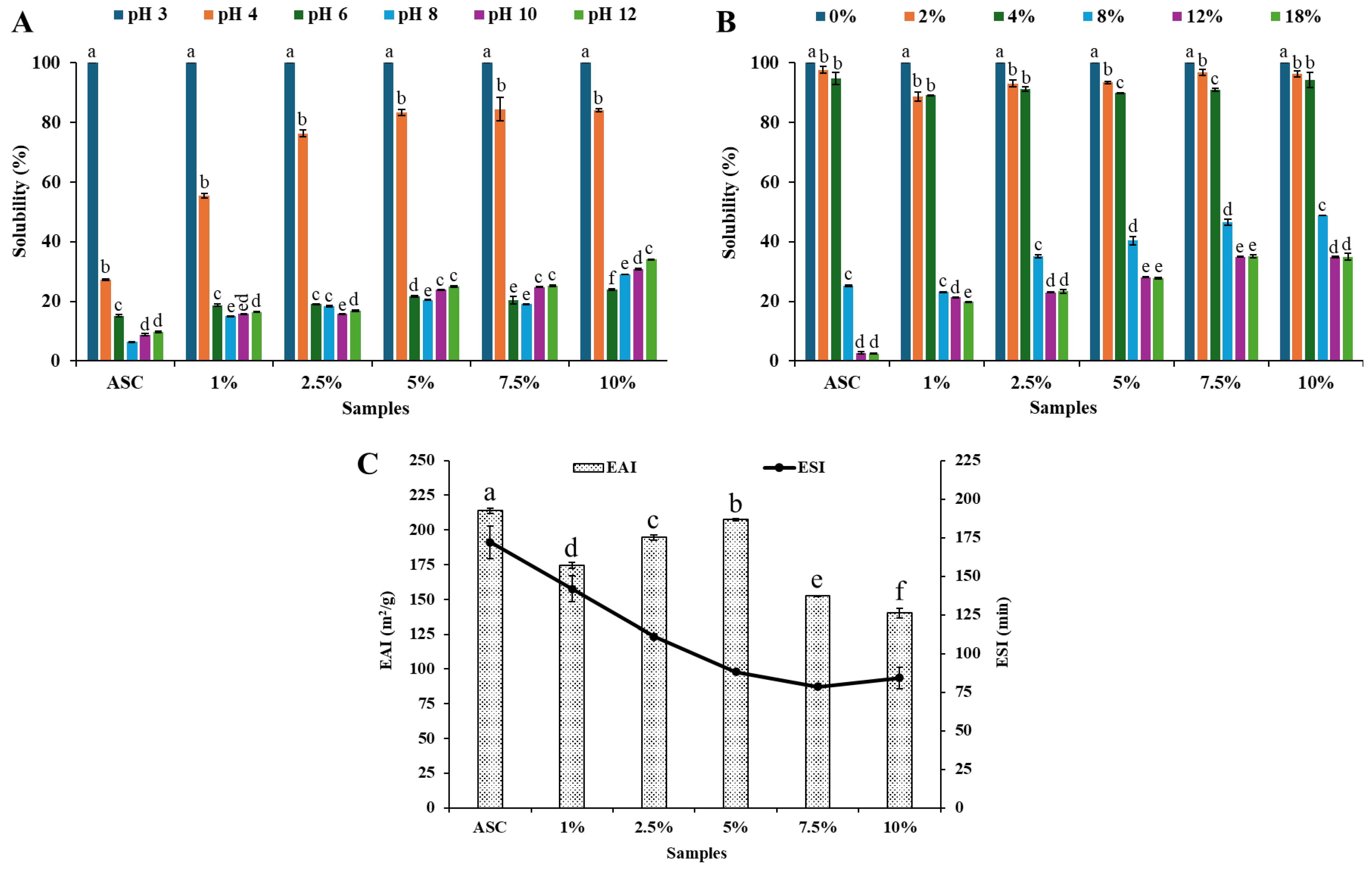

3.3. Effect of pH and NaCl on the Solubility of Collagen Samples

3.4. Emulsifying Properties of Collagen Samples

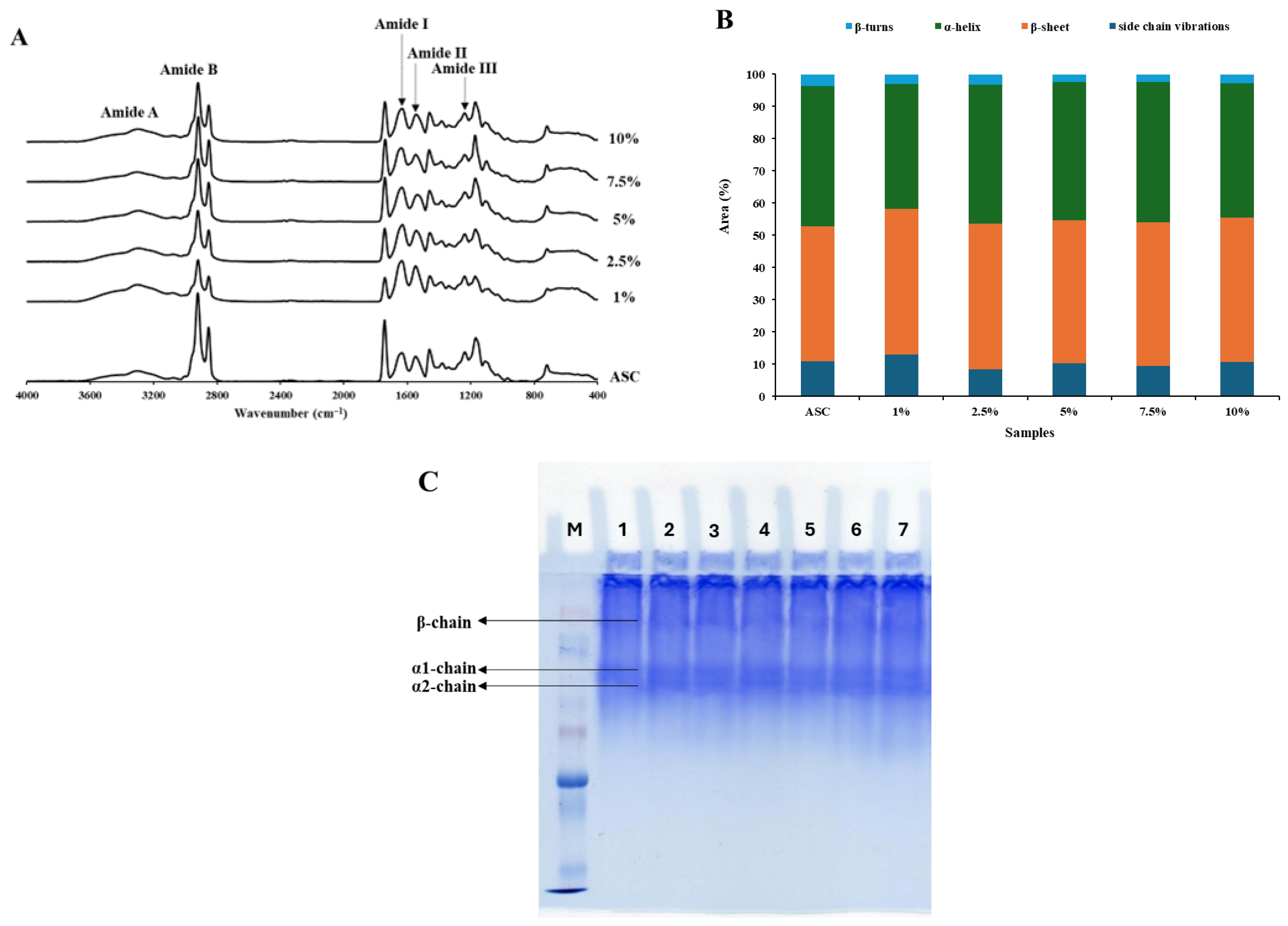

3.5. FTIR Spectra of Collagen Samples

3.6. Amino Acid Content and Composition of Collagen Samples

3.7. Protein Pattern of Collagen Samples

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAO. Total Meat Production—UN FAO. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/global-meat-production (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- FAO. Yearly Per Capita Supply of Other Meat. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/per-capita-meat-consumption-by-type-kilograms-per-year (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- USDA. Available online: https://www.fas.usda.gov/data/production/commodity/0111000 (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- AHDB. Beef Market Update: Shortages Forecast in Irish Cattle Numbers. Available online: https://ahdb.org.uk/news/beef-market-update-shortages-forecast-in-irish-cattle-numbers (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Export Performance and Prospects Report 2024–2025; Bord Bia—The Irish Food Board: Dublin, Ireland; Available online: https://www.bordbia.ie/industry/insights/publications/export-performance-and-prospects-2425/ (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Jadeja, R.; Teng, X.M.; Mohan, A.; Duggirala, K. Value-added utilization of beef by-products and low-value comminuted beef: Challenges and opportunities. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2022, 48, 100938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Nicola, V. Omentum a powerful biological source in regenerative surgery. Regen. Ther. 2019, 11, 182–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahraki, A.R.; Abaee, R.; Shahraki, E. Omentum a Powerful Viable Organ in Patient with Liver Crash Trauma: A Case Series. EAS J. Med. Surg. 2024, 6, 64–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meza-Perez, S.; Randall, T.D. Immunological functions of the omentum. Trends Immunol. 2017, 38, 526–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezvani Ghomi, E.; Nourbakhsh, N.; Akbari Kenari, M.; Zare, M.; Ramakrishna, S. Collagen-based biomaterials for biomedical applications. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 2021, 109, 1986–1999. [Google Scholar]

- Wosicka-Frąckowiak, H.; Poniedziałek, K.; Woźny, S.; Kuprianowicz, M.; Nyga, M.; Jadach, B.; Milanowski, B. Collagen and its derivatives serving biomedical purposes: A review. Polymers 2024, 16, 2668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Luo, X.; Liu, Y.; Teng, M.; Liu, X.; Zhang, X.; Liu, X. Edible packaging revolution: Enhanced functionality with natural collagen aggregates. Food Hydrocoll. 2024, 156, 110331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezati, P.; Khan, A.; Bhattacharya, T.; Zaitoon, A.; Zhang, W.; Roy, S.; Rhim, J.-W.; Lim, L.-T. Recent Advances in Collagen and Collagen-Based Packaging Materials: A Review. ACS Food Sci. Technol. 2025, 5, 1767–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawalbeh, D.; Kha’sim, M.I.; Mhd Sarbon, N.; Sarbon, N.M. Techno-functional and bioactivity properties of collagen hydrolysate and peptide: A review. Food Rev. Int. 2025, 41, 1509–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobasheri, A.; Mahmoudian, A.; Kalvaityte, U.; Uzieliene, I.; Larder, C.E.; Iskandar, M.M.; Kubow, S.; Hamdan, P.C.; de Almeida, C.S., Jr.; Favazzo, L.J. A white paper on collagen hydrolyzates and ultrahydrolyzates: Potential supplements to support joint health in osteoarthritis? Curr. Rheumatol. Rep. 2021, 23, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birk, D.E.; Brückner, P. Collagens, suprastructures, and collagen fibril assembly. In The Extracellular Matrix: An Overview; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 77–115. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, C.; Xiao, Y.; Ling, S.; Pei, Y.; Ren, J. Structure of collagen. In Fibrous Proteins: Design, Synthesis, and Assembly; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 17–25. [Google Scholar]

- Song, H.; Yin, B.; Jiang, B.; Mi, L.; Cui, C.; Su, W.; Bai, N. Characterization and Biological Performance of Anglerfish Collagen and Bovine Collagen. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2025, 197, 7431–7449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOAC. AOAC Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC International; AOAC International: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Brunton, N.; Mason, C.; Collins, M., Jr. Rapid microwave assisted preparation of fatty acid methyl esters for the analysis of fatty acid profiles in foods. J. Anal. Chem. 2015, 70, 1218–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabaha, K.; Taralp, A.; Cakmak, I.; Ozturk, L. Accelerated hydrolysis method to estimate the amino acid content of wheat (Triticum durum Desf.) flour using microwave irradiation. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 2958–2965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herbert, P.; Barros, P.; Ratola, N.; Alves, A. HPLC determination of amino acids in musts and port wine using OPA/FMOC derivatives. J. Food Sci. 2000, 65, 1130–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, P.; Petersen, D.; Dambmann, C. Improved method for determining food protein degree of hydrolysis. J. Food Sci. 2001, 66, 642–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjakul, S.; Morrissey, M.T. Protein hydrolysates from Pacific whiting solid wastes. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1997, 45, 3423–3430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, H.W.; Hogden, C.G. The biuret reaction in the determination of serum proteins. 1. A study of the conditions necessary for the production of a stable color which bears a quantitative relationship to the protein concentration. J. Biol. Chem. 1940, 135, 707–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-Ortíz, F.; Morón-Fuenmayor, O.; González-Méndez, N. Hydroxyproline measurement by HPLC: Improved method of total collagen determination in meat samples. J. Liq. Chromatogr. Relat. Technol. 2004, 27, 2771–2780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, S.K.; Zhang, C.H.; Lin, H.; Yang, P.; Hong, P.Z.; Jiang, Z.H. Isolation and characterisation of acid-solubilised collagen from the skin of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Food Chem. 2009, 116, 879–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaik, M.I.; Chong, J.Y.; Sarbon, N.M. Effect of ultrasound-assisted extraction on the extractability and physicochemical properties of acid and pepsin soluble collagen derived from Sharpnose stingray (Dasyatis zugei) skin. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2021, 38, 102218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowry, O.H.; Rosebrough, N.J.; Farr, A.L.; Randall, R.J. Protein Measurement with the Folin Phenol Reagent. J. Biol. Chem. 1951, 193, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laemmli, U.K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 1970, 227, 680–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ignat’eva, N.Y.; Danilov, N.; Averkiev, S.; Obrezkova, M.; Lunin, V.; Sobol’, E. Determination of hydroxyproline in tissues and the evaluation of the collagen content of the tissues. J. Anal. Chem. 2007, 62, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowes, J.H.; Elliott, R.; Moss, J. The composition of collagen and acid-soluble collagen of bovine skin. Biochem. J. 1955, 61, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pothoven, M.A.; Beitz, D.C.; Zimmerli, A. Fatty acid compositions of bovine adipose tissue and of in vitro lipogenesis. J. Nutr. 1974, 104, 430–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushi, D.E.; Thomassen, M.S.; Kifaro, G.C.; Eik, L.O. Fatty acid composition of minced meat, longissimus muscle and omental fat from Small East African goats finished on different levels of concentrate supplementation. Meat Sci. 2010, 86, 337–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hostens, M.; Fievez, V.; Leroy, J.L.M.R.; Van Ranst, J.; Vlaeminck, B.; Opsomer, G. The fatty acid profile of subcutaneous and abdominal fat in dairy cows with left displacement of the abomasum. J. Dairy Sci. 2012, 95, 3756–3765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezeshk, S.; Rezaei, M.; Abdollahi, M. Impact of ultrasound on extractability of native collagen from tuna by-product and its ultrastructure and physicochemical attributes. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2022, 89, 106129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.D.; Li, L.; Yi, R.Z.; Xu, N.H.; Gao, R.; Hong, B.H. Extraction and characterization of acid-soluble collagen from scales and skin of tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 66, 453–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.R.; Wang, B.; Chi, C.F.; Zhang, Q.H.; Gong, Y.D.; Tang, J.J.; Luo, H.Y.; Ding, G.F. Isolation and characterization of acid soluble collagens and pepsin soluble collagens from the skin and bone of Spanish mackerel (Scomberomorous niphonius). Food Hydrocoll. 2013, 31, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.-m.; Zhang, G.-y.; Bai, X.-y.; Yin, F.; Ru, A.; Yu, X.-l.; Zhao, L.-j.; Zhu, C.-z. Effects of NaCl-assisted regulation on the emulsifying properties of heat-induced type I collagen. Food Res. Int. 2022, 159, 111599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Liang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Chang, S.K.; Hong, H.; Luo, Y.; Tan, Y. Silver carp swim bladder collagen derived from deep eutectic solvents: Enhanced solubility against pH and NaCl stresses. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 281, 136315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, M.; Zhang, M.; Bian, H.; Wang, D.; Xu, W.; Wei, S.; Guo, R. Role of Medium-Chain Triglycerides on the Emulsifying Properties and Interfacial Adsorption Characteristics of Pork Myofibrillar Protein. Foods 2025, 14, 796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, X.D.; Yue, C.H.; Wang, Y.X.; Shao, M.L.; Yu, G.P. Effect of limited enzymatic hydrolysis on the structure and emulsifying properties of rice bran protein. J. Cereal Sci. 2019, 85, 168–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.H.; Zhang, Y.S.; Liu, X.M.; Huang, L.H.; Chen, Z.Y.; Cheng, J.R. Influence of hydrolysis behaviour and microfluidisation on the functionality and structural properties of collagen hydrolysates. Food Chem. 2017, 227, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaz, T.; Zeeshan, R.; Zarif, F.; Ilyas, K.; Muhammad, N.; Safi, S.Z.; Rahim, A.; Rizvi, S.A.; Rehman, I.U. FTIR analysis of natural and synthetic collagen. Appl. Spectrosc. Rev. 2018, 53, 703–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stani, C.; Vaccari, L.; Mitri, E.; Birarda, G. FTIR investigation of the secondary structure of type I collagen: New insight into the amide III band. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2020, 229, 118006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzzi Plepis, A.M.D.; Goissis, G.; Das-Gupta, D.K. Dielectric and pyroelectric characterization of anionic and native collagen. Polym. Eng. Sci. 1996, 36, 2932–2938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domene, C.; Jorgensen, C.; Abbasi, S.W. A perspective on structural and computational work on collagen. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2016, 18, 24802–24811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matinong, A.M.E.; Chisti, Y.; Pickering, K.L.; Haverkamp, R.G. Collagen extraction from animal skin. Biology 2022, 11, 905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.-R.; Sun, B.; Li, Y.-Y.; Hu, Q.-H. Characterization of acid-soluble collagen from the coelomic wall of Sipunculida. Food Hydrocoll. 2009, 23, 2190–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Wu, G. Roles of dietary glycine, proline, and hydroxyproline in collagen synthesis and animal growth. Amino Acids 2018, 50, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsuwan, K.; Fusang, K.; Pripatnanont, P.; Benjakul, S. Properties and characteristics of acid-soluble collagen from salmon skin defatted with the aid of ultrasonication. Fishes 2022, 7, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Benjakul, S.; Maqsood, S.; Kishimura, H. Isolation and characterisation of collagen extracted from the skin of striped catfish (Pangasianodon hypophthalmus). Food Chem. 2011, 124, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauza-Włodarczyk, M.; Kubisz, L.; Włodarczyk, D. Amino acid composition in determination of collagen origin and assessment of physical factors effects. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 104, 987–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameters | Values on Wet Weight Basis (%) |

|---|---|

| Moisture | 35.25 ± 2.51 |

| Crude protein | 18.79 ± 1.10 |

| Crude lipid | 42.14 ± 2.90 |

| Carbohydrates | 3.77 ± 0.71 |

| Ash | 0.06 ± 0.02 |

| Amino Acid | Amount (mg/g Wet Weight) | Fatty Acid | Amount (mg/g Wet Weight) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glycine | 43.10 ± 4.62 | SFA | |

| Phenylalanine | 22.80 ± 3.39 | C16:0 Palmitic acid | 72.97 ± 6.50 |

| Alanine | 22.29 ± 1.93 | C18:0 Stearic acid | 43.35 ± 3.80 |

| Glutamic acid | 22.41 ± 1.21 | C14:0 Myristic acid | 9.64 ± 2.35 |

| Methionine | 15.62 ± 0.88 | C17:0 Heptadecanoic acid | 2.64 ± 0.70 |

| Arginine | 12.81 ± 1.02 | C15:0 Pentadecanoic acid | 1.26 ± 0.31 |

| Lysine | 11.57 ± 0.29 | C20:0 Arachidic acid | 0.43 ± 0.08 |

| Hydroxyproline | 10.83 ± 0.45 | MUFA | |

| Aspartic acid | 8.95 ± 0.50 | C18:1n9c Oleic Acid | 87.65 ± 3.63 |

| Serine | 6.25 ± 0.29 | C16:1n7c Palmitoleic acid | 1.37 ± 0.15 |

| Histidine | 5.77 ± 0.20 | C17:1n7c Heptadecenoic acid | 1.35 ± 0.39 |

| Isoleucine | 5.59 ± 1.10 | C14:1n5c Myristoleic acid | 1.85 ± 0.49 |

| Threonine | 5.22 ± 0.19 | PUFA | |

| Proline | 3.88 ± 0.28 | C18:2n6c Linoleic acid | 2.20 ± 0.49 |

| Valine | 2.97 ± 0.31 | C18:3n4c 9,11,14-Octadecatrienoic acid | 0.99 ± 0.03 |

| Cysteine | 1.53 ± 0.24 | C18:3n3 alpha-Linolenic acid | 0.58 ± 0.07 |

| Tyrosine | 0.90 ± 0.08 | C18:2n6t Linolelaidic acid | 0.15 ± 0.03 |

| Leucine | 0.51 ± 0.07 | C20:3n6c 8,11,14-Eicosatrienoic acid | 0.13 ± 0.03 |

| EAA | 70.04 ± 4.02 | C20:4n6c Arachidonic acid | 0.13 ± 0.01 |

| NEAA | 131.42 ± 11.50 | C20:5n3c 5,8,11,14,17-Eisopentaenoic acid | 0.02 ± 0.00 |

| TAA | 202.98 ± 12.22 | C22:6n3c 4,7,10,13,16,19 Docosahexaenoic acid | 0.01 ± 0.00 |

| Treatment | Yield (%) | Hydroxyproline content (mg/g Sample) |

|---|---|---|

| ASC | 3.98 ± 0.09 e | 38.65 ± 0.67 a |

| E 1% | 4.98 ± 0.13 d | 27.08 ± 0.54 e |

| E 2.5% | 5.29 ± 0.05 c | 32.56 ± 0.61 d |

| E 5% | 7.07 ± 0.06 b | 33.65 ± 0.56 dc |

| E 7.5% | 11.13 ± 0.09 a | 33.63 ± 0.62 c |

| E 10% | 11.15 ± 0.03 a | 35.04 ± 0.53 b |

| Protana® Prime (%, w/w) | Degree of Hydrolysis (%) | Free Amino Acid Content (mM L-Leucine Equivalent) | Protein Content (mg/g wet Weight) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2.50 ± 0.11 a | 0.17 ± 0.01 e | 70.73 ± 1.63 a |

| 2.5 | 2.78 ± 0.37 a | 0.44 ± 0.01 d | 72.41 ± 1.57 a |

| 5 | 4.60 ± 0.22 b | 0.62 ± 0.02 c | 87.21 ± 5.07 b |

| 7.5 | 5.23 ± 0.30 c | 0.84 ± 0.01 b | 97.19 ± 2.76 c |

| 10 | 5.48 ± 0.19 d | 1.41 ± 0.01 a | 102.93 ± 2.74 d |

| Amino Acid | ASC | 1% | 2.5% | 5% | 7.5% | 10% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aspartic acid | 21.63 a (32) | 17.63 c (37) | 19.48 b (30) | 15.01 e (24) | 14.91 e (20) | 16.49 d (26) |

| Glutamic acid | 67.74 a (91) | 45.63 e (86) | 57.16 b (80) | 45.93 e (66) | 51.93 c (61) | 50.24 d (71) |

| Serine | 19.39 a (37) | 12.66 e (34) | 15.86 c (31) | 13.94 d (28) | 16.89 b (28) | 15.55 c (31) |

| Histidine | 10.39 a (13) | 10.18 a (18) | 10.30 a (14) | 9.92 b (14) | 6.74 c (8) | ND (ND) |

| Arginine | 43.96 a (50) | 20.61 e (33) | 35.95 c (43) | 12.37 f (15) | 36.88 b (37) | 32.74 d (39) |

| Glycine | 120.55 b (318) | 71.87 f (265) | 106.42 e (295) | 109.92 d (313) | 142.94 a (331) | 115.98 c (322) |

| Threonine | 12.16 a (20) | 9.41 c (22) | 11.48 b (20) | 11.51 b (21) | 12.41 a (18) | 11.90 b (21) |

| Alanine | 71.74 c (159) | 44.75 e (139) | 72.64 c (170) | 67.23 d (162) | 108.14 a (211) | 74.81 b (174) |

| Tyrosine | 6.83 d (7) | 9.49 c (15) | 21.49 a (24) | 10.22 b (12) | 5.34 e (5) | 7.37 d (8) |

| Hydroxyproline | 30.43 a (46) | 24.34 d (52) | 25.56 c (41) | 25.50 c (42) | 25.01 c (33) | 26.02 b (41) |

| Valine | 5.49 a (9) | 4.33 c (10) | 3.20 b (6) | 4.02 b (7) | 2.46 d (4) | 3.37 c (6) |

| Methionine | 35.66 d (47) | 27.41 e (51) | 42.10 c (59) | 46.49 b (66) | 53.38 a (62) | 41.76 c (58) |

| Cysteine | 2.28 b (4) | 2.40 b (6) | 1.81 c (3) | 9.07 a (15) | 1.94 c (3) | 2.37 b (4) |

| Phenylalanine | 48.15 f (58) | 57.31 d (97) | 49.75 e (63) | 59.70 b (79) | 61.28 a (64) | 58.10 c (74) |

| Proline | 29.71 c (51) | 25.59 e (62) | 28.18 d (51) | 33.06 a (62) | 33.03 a (50) | 31.14 b (57) |

| Lysine | 28.36 e (38) | 19.82 f (38) | 29.06 d (41) | 29.75 c (44) | 35.61 a (42) | 30.38 b (43) |

| Isoleucine | 9.59 b (15) | 9.94 a (21) | 9.99 a (16) | 9.65 b (16) | 9.67 b (13) | 10.16 a (16) |

| Leucine | 2.70 e (4) | 6.39 c (14) | 8.17 a (13) | 8.32 a (14) | 7.08 b (9) | 4.85 d (8) |

| EAA | 152.49 e | 144.79 f | 164.04 c | 179.35 b | 188.63 a | 160.53 d |

| NEAA | 411.977 b | 272.57 f | 382.74 c | 333.18 e | 435.07 a | 370.33 d |

| TAA | 566.64 b | 419.77 e | 548.59 c | 521.61 d | 625.64 a | 533.24 d |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Mittal, A.; Collins, C.; Madden, L.; Brunton, N. Collagen from Bovine Omentum: Extraction and Characterization. Foods 2026, 15, 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010044

Mittal A, Collins C, Madden L, Brunton N. Collagen from Bovine Omentum: Extraction and Characterization. Foods. 2026; 15(1):44. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010044

Chicago/Turabian StyleMittal, Ajay, Catherine Collins, Lena Madden, and Nigel Brunton. 2026. "Collagen from Bovine Omentum: Extraction and Characterization" Foods 15, no. 1: 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010044

APA StyleMittal, A., Collins, C., Madden, L., & Brunton, N. (2026). Collagen from Bovine Omentum: Extraction and Characterization. Foods, 15(1), 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010044